Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Remains of A Dream

Загружено:

Harithra11Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Remains of A Dream

Загружено:

Harithra11Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

REMAINS OF A DREAM

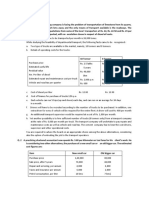

This is a tragic story, narrated in first person, of an entrepreneur who became bankrupt for no fault of him, without producing anything, mostly because of the irresponsible political and government environment. This case study, documented by Bibek Debroy and P.D. kaushik and published in Business today is reproduced here with permission. In the 1980s, I worked as a chemical analyst for a transnational in Germany, but kept thinking about shifting to India. Opportunity knocked when I saw an advertisement by the Uttar Pradesh government inviting NRI professionals to start a chemical unit in the newly identified Basti Chemical Industrial Complex. I hail from Lucknow. Hence, this was attractive. I inquired from the Indian High Commission and was told that there is single window clearance for NRI investors. The brochure said several things about the benefits-exercise and sales tax holiday for five years, uninterrupted power supply, low rate of interest on loans, and clearance of application within 30 days. I started the application formalities for a chemical unit. Once the application was accepted, I requested long leave from employers. I also inquired from my relatives in Lucknow and was told that the Uttar Pradesh governments intentions are clear, and developmental work is progressing at fast speed. Every now and then, I received a letter from the ministry of industry in Uttar Pradesh to furnish the paper or the other, as a part of procedural formalities. After three months, I received my provisional sanction letter for allotment of land, and term loan. The letter also stated that within six months, I must take possession of the land, and initiate construction. Otherwise, the deposited amount (Rs.1 lakh as part of my contribution) will be forfeited. I resigned from the company, and shifted permanently to India, since my employer turned down my request for long leave. On reaching the complex, I was surprised to see that the Uttar Pradesh State Industrial Development corporation had actually developed the land in terms of markers, and signboards, compared to what I had seen on my last visit.

Though roads were not fully laid, it was evident that work was in progress. I took possession of my land and started construction. Meanwhile, I approached the UPFC for granting me the term loan for ordering the plant and machinery. The first obstacle came from the Uttar Pradesh State Electricity Board (now Uttar Pradesh Power Corporation). The electricity supply to the complex was not yet available. On inquiring, I was told that the plan had been sanctioned, but required clearance from the power ministry, before undertaking further work. The approximate time to get grid supply ranged between four and six months. The next obstacle came from the Uttar Pradesh Financial Corporation (UPFC). It could release the first instalment after I completed construction till the plinth level. I continued work with the help of a diesel generating set. It took another month to reach the plinth level. But before I could request UPFC to release my first instalment, I received a letter from UPFC that I had to deposit interest against the amount paid to the UPSIDC for land possession. This was a shock, because interest had to be paid even before anything was produced. But I had no alternative, because the first instalment was due. The UPFC promptly released the first instalment after inspecting the construction. It helped me continue construction work, and also book for plant and machinery. Six months went by. Construction was almost complete. I had received three instalments from the Uttar Pradesh Financial Corporation (UPFC). Each time the payment of interest was due, the required sum was adjusted from the instalment released, If there was any shortfall in money required for construction, I paid from my own pocket. But after nine months, my coffers were empty. Machinery suppliers were after me, for payment. UPFC insisted on interest payments, because this was the last instalment of my term loan and interest due couldnt be deducted from future instalments. I borrowed from family and friends and paid up. Then I received the final instalment from UPFC for plant and machinery, with another notice that the yearly instalment for the principal was due.

Within two months, machinery was commissioned at the site. But electricity was yet to reach the complex. In the previous year, I had visited the Uttar Pradesh State Electricity Board (UPSED) office innumerable times. I also approached the industry association to assist me. But all my efforts were in vain. This did not help me, or others like me, to get the grid supply. There were 14 others who were in the same boat. The biggest company of them all--obviously with contacts at higher levels--arranged for grid supply from the rural feeder. But that plan also did no take off, because the rural feeder supplied poor quality power for a mere six hours. A process industry required 24 hours of uninterrupted electricity supply without load fluctuations. It is precisely because of this that all of 15 of us, who were waiting for electricity, had insisted on industrial power from UPSEB. All plans failed. Captive generation was not a viable alternative now. And we continued to wait for the grid supply. We met the former minister for industry and pleaded out case. He assured us that he would take up the case with the power ministry. Meanwhile, I defaulted on interest payments. So did the others. The final blow came in the Assembly elections, when both the sitting: Member of Legislative Assembly, from Basti, and the state industrial minister lost their seats. Suddenly, everything--from road construction work, to the laying of sewer and phone lines--came to a standstill. Only the police post and the UPSKB rural feeder office remained. The new incumbent in the industrial ministry hailed from Saharanpur, so the thrust of the ministry changed. Basti was not on their priority list anymore. After waiting for two years, UPSEB was not able to connect the complex with grid supply. In the end, UPFC initiated recovery action and sealed my unit. Besides, they claimed that I could not get NRI treatment, with preferential interest rates, because I had permanently moved to India. Thus here were also plans to file a case against me on account of misinforming the corporation. Experts suggested I should file for insolvency if wanted to avoid going to prison. This I did in 1994. I spent Rs. 15 lakh from my own pocket.

Now, all the remains of an entrepreneurial dream is sealed chemical unit in Basti and a complex legal tangle. I was better off working for the transnational in Germany. Power does not come out of the barrel of a gun. A guns barrel comes out of power, especially when the latter does not exist.

QUESTIONS: 1. Identify and analyze the environmental factors in this case. 2. Who were all responsible for this tragic end? 3. Is it right on the part of the government and promotional agencies to woo entrepreneurs by promising facilities and incentives which they are not sure of being able to provide? 4. Should be legislation to compensate entrepreneurs for the loss suffered due to the irresponsibility of public agencies? What problems are likely to be solved and created by such legislation? 5. what are the lessons of this case for an entrepreneur and government and promotional agencies?

Вам также может понравиться

- Case Study-Remains of A DreamДокумент2 страницыCase Study-Remains of A Dreamaksr27Оценок пока нет

- Vision and Mission Statement and Its Analysis On SuzlonДокумент5 страницVision and Mission Statement and Its Analysis On Suzlondev shahОценок пока нет

- Case StudyДокумент3 страницыCase Studyjohnleh1733% (3)

- Analysis of Working Capital of Ambuja and ACC Cement Final ReportДокумент13 страницAnalysis of Working Capital of Ambuja and ACC Cement Final ReportAnuj GoelОценок пока нет

- Western Coalfields - Story of A Buying ProcessДокумент6 страницWestern Coalfields - Story of A Buying ProcessVarsha MoharanaОценок пока нет

- Case Study MobДокумент1 страницаCase Study MobRamamohan ReddyОценок пока нет

- Fa IiiДокумент76 страницFa Iiirishav agarwalОценок пока нет

- Finquilibria - Case Study: Deluxe Auto LimitedДокумент4 страницыFinquilibria - Case Study: Deluxe Auto LimitedAryan SharmaОценок пока нет

- Financial Management 2E: Rajiv Srivastava - Dr. Anil MisraДокумент5 страницFinancial Management 2E: Rajiv Srivastava - Dr. Anil MisraAnkit AgarwalОценок пока нет

- BRM0012 - Consumer's Perception On Inverters in IndiaДокумент3 страницыBRM0012 - Consumer's Perception On Inverters in Indiavarun kumar Verma0% (2)

- The Satyam Computers ScamДокумент11 страницThe Satyam Computers ScamTushar Sahu100% (1)

- Leader in CSR 2020: A Case Study of Infosys LTDДокумент19 страницLeader in CSR 2020: A Case Study of Infosys LTDDr.Rashmi GuptaОценок пока нет

- Questions On Budgets SPPU MBA Sem 1Документ7 страницQuestions On Budgets SPPU MBA Sem 1Ketan IngaleОценок пока нет

- Cashflow and Fund FlowДокумент17 страницCashflow and Fund FlowHarking Castro ReyesОценок пока нет

- Case StudyДокумент7 страницCase StudyRaam Tha BossОценок пока нет

- What Are Some Examples of HR Events at A B-School College FestДокумент1 страницаWhat Are Some Examples of HR Events at A B-School College Festgorika chawlaОценок пока нет

- Problems On Hire Purchase and LeasingДокумент5 страницProblems On Hire Purchase and Leasingprashanth mvОценок пока нет

- FA 08 Depreciation ProblemsДокумент5 страницFA 08 Depreciation ProblemsPranav Latkar0% (2)

- Case Description of Dovernet Case StudyДокумент8 страницCase Description of Dovernet Case StudyAnjali GoelОценок пока нет

- Decision Theory - I-18Документ4 страницыDecision Theory - I-18NIKHIL SINGHОценок пока нет

- Telenor UnderdogДокумент14 страницTelenor UnderdogSandeep MishraОценок пока нет

- TVM Sums & SolutionsДокумент7 страницTVM Sums & SolutionsRupasree DeyОценок пока нет

- Decision Sheet - MdbsДокумент3 страницыDecision Sheet - MdbsGayatri BommisettyОценок пока нет

- Final Report of Shree CmsДокумент117 страницFinal Report of Shree CmsPuneet DagaОценок пока нет

- ProjectДокумент18 страницProjectpatel2431Оценок пока нет

- KRDTop100SFM PDFДокумент215 страницKRDTop100SFM PDFNag Sai NarahariОценок пока нет

- Videocon (Marketing Strategy)Документ66 страницVideocon (Marketing Strategy)Anam Khan100% (1)

- Amazon Vs Future Retail Case SummaryДокумент3 страницыAmazon Vs Future Retail Case Summarybharat bhatОценок пока нет

- Group 2 Session 3 BMUC CaseДокумент20 страницGroup 2 Session 3 BMUC CaseRomali DasОценок пока нет

- ME (1st) May2019Документ2 страницыME (1st) May2019Tanya GrewalОценок пока нет

- Cases Karkraft & Valley TransportersДокумент2 страницыCases Karkraft & Valley TransportersAvirup ChatterjeeОценок пока нет

- Modi Rubber Vs Financial Institution Case PresentationjДокумент27 страницModi Rubber Vs Financial Institution Case PresentationjGaurav AgarwalОценок пока нет

- Numericals On Cost of Capital and Capital StructureДокумент2 страницыNumericals On Cost of Capital and Capital StructurePatrick AnthonyОценок пока нет

- Assignment Guide 20200403110201 443Документ6 страницAssignment Guide 20200403110201 443Hrushiraj AdsulОценок пока нет

- Videocon Case StudyДокумент14 страницVideocon Case Studyuse lessОценок пока нет

- ABC Wealth AdvisorsДокумент5 страницABC Wealth AdvisorsUjwalsagar Sagar33% (3)

- PRESENTATION On Tata Motors LkoДокумент43 страницыPRESENTATION On Tata Motors Lkozaid khanОценок пока нет

- Cash BudgetДокумент2 страницыCash BudgetanupsuchakОценок пока нет

- HLL Bblil MergerДокумент12 страницHLL Bblil MergerBhudev Kumar SahuОценок пока нет

- Interim Report PDFДокумент33 страницыInterim Report PDFanugya jainОценок пока нет

- Service CostingДокумент6 страницService Costingbinu100% (1)

- Factoring and ForfaitingДокумент34 страницыFactoring and ForfaitingStone HsuОценок пока нет

- PESTEL Analysis of Banking and Insurance Industry 11Документ10 страницPESTEL Analysis of Banking and Insurance Industry 11Dhananjayrao mhatreОценок пока нет

- Taxation Management Notes Tax Year 2020Документ61 страницаTaxation Management Notes Tax Year 2020Ramsha ZahidОценок пока нет

- IGTC Contract Labour Case StudiesДокумент7 страницIGTC Contract Labour Case StudiesronakОценок пока нет

- Mid Sem 1sem Exam Paper Oct2015Документ26 страницMid Sem 1sem Exam Paper Oct2015angel100% (1)

- Case Studies On Demand Analysi1Документ1 страницаCase Studies On Demand Analysi1ramkrishnagnОценок пока нет

- Chapter - 12: Risk Analysis in Capital BudgetingДокумент28 страницChapter - 12: Risk Analysis in Capital Budgetingrajat02Оценок пока нет

- FAC133 FM - Capital Budgeting SumsДокумент9 страницFAC133 FM - Capital Budgeting SumsVedant Vinod MaheshwariОценок пока нет

- Liberalisation, Privatisation and GlobalisationДокумент15 страницLiberalisation, Privatisation and GlobalisationShruti KurupОценок пока нет

- Tata Chemicals Case Study - International MKTGДокумент5 страницTata Chemicals Case Study - International MKTGJohn_Fernandes_7150Оценок пока нет

- Karan Miraj ReportДокумент31 страницаKaran Miraj Reportvarun_jain_mba15Оценок пока нет

- MBA/D-21 Financial Reporting, Statements and AnalysisДокумент2 страницыMBA/D-21 Financial Reporting, Statements and AnalysisSuman Naveen JaiswalОценок пока нет

- Capital Budgeting Case 1-Sec C, 18-20Документ1 страницаCapital Budgeting Case 1-Sec C, 18-20Mayank JAin0% (1)

- Report On Rental Power PlantДокумент4 страницыReport On Rental Power Plantahkhan4Оценок пока нет

- Business Environment Case Study Dvishnu DevaДокумент11 страницBusiness Environment Case Study Dvishnu DevaD VISHNU DEVAОценок пока нет

- 10jun Land Availability IssuesДокумент7 страниц10jun Land Availability Issuesabhinavs02Оценок пока нет

- The Anatomy of Corruption: Exercising The People's Right To InformationДокумент12 страницThe Anatomy of Corruption: Exercising The People's Right To InformationThe Ramon Magsaysay AwardОценок пока нет

- Proof Affidavit - CC No-147Документ11 страницProof Affidavit - CC No-147Amol RajОценок пока нет

- Sikkim State Human Rights CommissionДокумент12 страницSikkim State Human Rights CommissionKalpita SahaОценок пока нет

- Decision MakingДокумент41 страницаDecision MakingRohit VermaОценок пока нет

- Remains of A DreamДокумент17 страницRemains of A DreamHarithra11Оценок пока нет

- Decision MakingДокумент26 страницDecision MakingAmit JainОценок пока нет

- Decision Making Power Point Content 1222366586635597 9Документ13 страницDecision Making Power Point Content 1222366586635597 9Murtaza RiyazОценок пока нет

- Major Oils: Production of Oilseeds (Source: Directorate of Economic & Statistics)Документ2 страницыMajor Oils: Production of Oilseeds (Source: Directorate of Economic & Statistics)Harithra11Оценок пока нет

- KFC FinalДокумент25 страницKFC FinalBappy Vanja0% (1)

- Toungue Twisters - 10 CopiesДокумент1 страницаToungue Twisters - 10 CopiesHarithra11Оценок пока нет

- What Is Halal FoodДокумент2 страницыWhat Is Halal FoodHarithra11Оценок пока нет

- Descriptive Ethics - Encyclopedia of Business EthicsДокумент5 страницDescriptive Ethics - Encyclopedia of Business Ethicssimply_cooolОценок пока нет

- Ritz Carlton Case StudyДокумент20 страницRitz Carlton Case Studylucky75Оценок пока нет

- Quality MGMT KFCДокумент16 страницQuality MGMT KFCKesmavet Fkh UgmОценок пока нет

- RBI MoneyKumar ComicДокумент24 страницыRBI MoneyKumar Comicbhoopathy100% (1)

- RBI MoneyKumar ComicДокумент24 страницыRBI MoneyKumar Comicbhoopathy100% (1)

- RB Annual Report 2012Документ88 страницRB Annual Report 2012Harithra11Оценок пока нет

- Questionnaire Regarding SurveyДокумент3 страницыQuestionnaire Regarding SurveyHarithra11Оценок пока нет

- The Daniela Garcia StoryДокумент14 страницThe Daniela Garcia StoryHarithra11Оценок пока нет

- Research On Fastrack WatchesДокумент23 страницыResearch On Fastrack Watcheskk_kamal40% (5)

- Er DigramДокумент1 страницаEr DigramHarithra11Оценок пока нет

- Technopath yДокумент2 страницыTechnopath yHarithra11Оценок пока нет

- Softskill (PSG CAS Students)Документ34 страницыSoftskill (PSG CAS Students)Harithra11Оценок пока нет

- The Accounting EquationДокумент14 страницThe Accounting EquationErickk EscanooОценок пока нет

- Summary of Money Market and Monetary Operations in IndiaДокумент1 страницаSummary of Money Market and Monetary Operations in IndiaSubigya BasnetОценок пока нет

- Forex Reserves in IndiaДокумент3 страницыForex Reserves in IndiaJohn BairstowОценок пока нет

- Long Term Financial PlanningДокумент17 страницLong Term Financial PlanningSayed Mehdi Shah KazmiОценок пока нет

- 7 Adjustments To Final AccountsДокумент11 страниц7 Adjustments To Final AccountsBhavneet SachdevaОценок пока нет

- Triangular ArbitrageДокумент5 страницTriangular ArbitrageSajid HussainОценок пока нет

- Comparative Analysis of The Home Loan of Sbi in Bharuch: Prepared byДокумент14 страницComparative Analysis of The Home Loan of Sbi in Bharuch: Prepared byBhavini UnadkatОценок пока нет

- Cash Flow - Alpa Beta GammaДокумент26 страницCash Flow - Alpa Beta GammaAnuj Rakheja67% (3)

- Syllabus Macro 1Документ5 страницSyllabus Macro 1pratyush1984100% (1)

- Questions For Advanced AccountingДокумент3 страницыQuestions For Advanced AccountingHelena ThomasОценок пока нет

- AssignmentДокумент4 страницыAssignmentshahin317Оценок пока нет

- Spouses Deo Agner and Maricon Agner v. Bpi Family Savings Bank Inc. GR No. 182963Документ2 страницыSpouses Deo Agner and Maricon Agner v. Bpi Family Savings Bank Inc. GR No. 182963Jaypee Ortiz67% (3)

- Fact and Fiction in Eu Governmental Economic Data PDFДокумент2 страницыFact and Fiction in Eu Governmental Economic Data PDFJulieОценок пока нет

- Credit ManagementДокумент29 страницCredit ManagementDipesh KaushalОценок пока нет

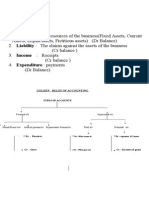

- 1.cash Basis 2.accrual Basis: Golden Rules of AccountingДокумент4 страницы1.cash Basis 2.accrual Basis: Golden Rules of AccountingabinashОценок пока нет

- Demo Quiz - 1Документ10 страницDemo Quiz - 1Rohit GuptaОценок пока нет

- New IMF Program by Dr. Ashfaque H. KhanДокумент2 страницыNew IMF Program by Dr. Ashfaque H. KhanresfreakОценок пока нет

- Term Paper - LLCДокумент9 страницTerm Paper - LLCapi-115328034Оценок пока нет

- CIBIL Decision MatrixДокумент3 страницыCIBIL Decision MatrixsureshkayambuОценок пока нет

- CF Chapter Two QuestionsДокумент2 страницыCF Chapter Two Questionszaraazahid_950888410Оценок пока нет

- Analyzing Transactions and Double EntryДокумент40 страницAnalyzing Transactions and Double EntrySuba ChaluОценок пока нет

- Intrest Rate StructureДокумент12 страницIntrest Rate StructureMohit KumarОценок пока нет

- World Trade: An Overview: Slides Prepared by Thomas BishopДокумент36 страницWorld Trade: An Overview: Slides Prepared by Thomas BishopAbu Naira HarizОценок пока нет

- Book Keeping and Accounts Past Paper Series 2 2011Документ6 страницBook Keeping and Accounts Past Paper Series 2 2011Aggelos Ispirli0% (1)

- Motion To Dismiss-Fleury Chapter 7 BankruptcyДокумент5 страницMotion To Dismiss-Fleury Chapter 7 Bankruptcyarsmith718Оценок пока нет

- Use The Following Information For Questions 1 and 2Документ5 страницUse The Following Information For Questions 1 and 2Jane Michelle Eman0% (2)

- Indexed Irish Equity Fund: Fund Description Fund FactsДокумент2 страницыIndexed Irish Equity Fund: Fund Description Fund Factsrowland_smithersОценок пока нет

- ITP - Foreign Exchange RateДокумент29 страницITP - Foreign Exchange RateSuvamDharОценок пока нет

- Lecture 2Документ38 страницLecture 2Tiffany TsangОценок пока нет

- Tesco Credit AgreementДокумент25 страницTesco Credit AgreementM.r. KhanОценок пока нет