Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Metamorphoses of Fat: A History of Obesity

Загружено:

Columbia University PressАвторское право

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

The Metamorphoses of Fat: A History of Obesity

Загружено:

Columbia University PressАвторское право:

Copyrighted Material

introduction

In one of her letters from the end of the seventeenth century, Elizabeth Charlotte, the Palatine Princess, gives the reader this image of herself: my waist is monstrously wide, I am as square as a cube, my skin is red, speckled with yellow.1 This testimony is precious because physical self-description is rare in old regime France. It supposes a distance, an objectification of the self, a dominating judgment that only a slow process of cultural labor could make possible. The testimony is especially valuable because it confirms that a definitive change in thinking has occurred: big is now only bad. The princess insists on the disgrace, the heaviness, the irremediable descent from feathery to fat that places her among the ugly.2 Then come anecdotes naming the symptoms of various troubles and ailments: spleen pain, colic, vapors, and a loss of balance worsened by bumpy carriages. Being big is a disadvantage, perhaps even a curse. The big person, however, was not always so strongly denounceda fact that justifies historical inquiry. Massive bodies can be praised in the Middle Ages, for example, as denoting power and ascendancy. Similarly, in times of hunger, admiring praise is accorded to lands of plenty [pays de cocagne] with all-you-can-eat banquets and visions of endlessly stuffing oneself. Force is associated with the large hearty meal. Accumulating pounds is seen as health insurance. And social privilege is signified through a display of ones own size. These ideas are probably complicated as well, though, because even in the Middle Ages they are contested by the sermons of clerics and the reservations and beliefs of doctors and even

Copyrighted Material

xIntroduction

by the delicately phrased demands of courtly codes. Nevertheless, they are impressive, immediately recognizable signs that lend the big person power and conviction. A definitive break however takes place with the advent of modern Europe. The closely contemporary testimonies of Saint-Simon in France and Samuel Pepys in England denigrate a lazy, fat priest,3 deride a fat child called Punch, a word of common use for all that is thick and short,4 big, fat creatures,5 and fat and lusty and ruddy courtiers,6 while Madame de Svign fears above all becoming a flattened fatty.7 The big person [le gros] is now only a fat person [le gras]indolent and collapsed.8 Prestige and models change. The rough tables of olden times heaped with food are no longer classy, and accumulating pounds of flesh is no longer a sign of forceful reserves but rather of a certain loss of control and grossness. The history of being big is the story of these reversals. The development of Western societies promotes a tendency toward slimmer bodies, a keener supervision of physical contours, and an increasingly alarmed refusal of heaviness. This of course brings changes in what counts as big and a barely imperceptible but steady privileging of lightness. This in turn strongly exacerbates contempt for big people, who find themselves increasingly discredited. Voluminous individuals fall further and further below standards of refinement, while beauty is ever more associated with the thin and slender. This same discredit takes on a different content over time and these changes further justify a history of bigness. The vision of the fault shifts, thus revealing how much the bodys appearance, with its real or supposed flaws, is linked to a history of cultures and sensibilities. Medieval criticisms, formulated by clerics and diffused with some success in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in advance of our modern era, insist on the capital or deadly sins. These criticisms assail the passions, single out the glutton, and denounce his lack of dignity. They condemn avarice, while modern criticisms insist on a lack of dexterity and efficiency. The big, now fat, person becomes a figure of the inapt, the unfitflabby and inert. Their fault is a deficit of doing, an insufficiency of power and action. Annibal Carraches caricature portraits from the seventeenth century are the best illustrations: groups of men with oversized stomachs and short limbs stuck in poses of heaviness.9 The flaw of the fat person in modern times is lack of dynamism and a capacity for doing. The dominant idea becomes fat = no power. The fat person can also provoke collective denunciations, as when the full chests of the wealthy are pointed to as a sign either of

Copyrighted Material

Introductionxi

their rapaciousness or their true inefficiency. With their round tummies and degraded bodies, aristocrats and abbots at the end of the eighteenth century are the classic examplesprofiteers that revolutionary ideas will squeeze down, then out, thus exposing their uselessness. Criticisms also become more psychological as societies accentuate individualism and valorize autonomy and self-affirmation. The losers in these accounts are more intimate, emotional cases. Hence the apathy10 that weighty anatomies are reproached for in northern countries in the late eighteenth century, or the egoism11 held against the fat person in the proto-sociological portraits of Romantic literature; for example, the young bullied kid, fat and sad, as described by Granville in his Small Miseries of Human Life (1843).12 Size comes definitively to be thought of as correlating with individual attitudes and personality traits and even ways of thinking. At the end of the nineteenth century, Manuel Leven goes so far as to write up a long series of treatises associating neurosis and obesity.13 The criticism of the fat person thus participates in the immense shift within Western societies that deepens the space given over to psychologiestaking distance from older moral classifications and instead developing an infinite array of personal differentiations and types of behavior. In other words, this stigmatization reflects above all an accentuation of norms that in Western societies dictated ever stricter rules and precise guidelines for physical appearance and the expression of self. It can also reflect differences that are upheld between male and female genders as well as between social groups. For example, public condemnation is more severe toward the female body, which has been traditionally expected to be supple and fluid. Inversely, judgments have been more tolerant toward the dominant sex whose ascendancy has traditionally allowed for a more imposing voluminous size. The court of the great king in the seventeenth century, for example, does not lack for princes of a certain rotund stature, just as in the nineteenth-century world of the bourgeois there is no shortage of figures whose prestige is marked by a certain hefty, not to say heavy, allure. Here, too, social and cultural polarities, the differences constructed between men and women, inevitably traverse both positive and negative judgments. Obviously the history of the big and the fat is also the history of the valuations of bodily forms and the work theyre put to. For a long time these judgments remain imprecise because of a lack of measurable, statistical criteria. For a long time the intermediary stages or types between normal and very big are not clearly described. It takes a slow, gradual

Copyrighted Material

xiiIntroduction

invention of a set of terms and diminutives between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to suggest a scale of chubbiness, posit types, and attempt to formalize them despite the inevitable persistence of imprecision.14 The increasing variety of terms testifies to the increasing discrimination of the eye, even though its judgment remained rather approximate and even disappointing by todays standards for quite a while. We may note the insistent affirmation in a Dictionnaire de mdecine from 1827 that fatness presents a multitude of degrees.15 A history of the body must give an account of both these evaluations of appearances and the history of their ever more explicit elaboration. A sign of this growing exactitude is the statistical calculation and report of body weight that becomes customary by the end of the nineteenth century, just as an increasingly industrious vision of bodies and anatomies is also taking hold. It will take time before the bathroom scale and related personal tools arrive in private spaces in the twentieth century, marking a new requirement for self-maintenance that the evidence of periodic self-weighing fulfills. The presence of the scale has become part of everyday life, almost natural, so spontaneous that it can make us forget how much our judgments of weight developed and refined themselves before the advent of numbers and tests. But it is this refinement and its diversification and individualization that are central to a history of big people. Finally there are the fitness tactics and strategies for fighting fat as priority is gradually given over to slimming within Western societies. These practices also accelerate through the modern era, diversifying over time, revealing that the fight against weight is not a new invention but accompanies the gradual refinement of judgment about bodily curves and their modifications. For a long time this battle had as its first principle the constraint exerted on the skin itself: the corset, the girdle, and straps of all sorts. As though the bodys forms had to obey the most material manipulations, as though they had to yield to the tightest strictures. At bottom this is nothing but the expression of an archaic belief that targets the body as a passive ensemble, a consummately malleable object, a material submissive to the simplest mechanical corrections. This fight against fat has a new dimension that has not received much historical attention despite its impact, namely, that a project of getting thin can encounter limits and even impossibilities. Not that it is always deficient. Successes continue to multiply, linked to this or that scientific breakthrough. But the resistances also multiplycurves and weight go unchanged despite the accumulation of treatments. The obstruction can then become an obsession, a site of growing worry as knowledge devel-

Copyrighted Material

Introductionxiii

ops to sophisticated levels, and alarms ring as diet procedures become an obligatory practice. The stigmatization thus shifts from a denigration of fat to a denigration of powerlessness, the inability to change. The reprobation becomes more psychological, more intimate; they are no longer accusations of awkwardness or gluttony, but of nonmastery, a lack of power over oneself as one keeps an impassive and ugly body whereas everything says it ought to change. The history of obesity is also the history of these inertias, of a body ever more identified with a person in Western history, and yet that body escapes from certain attempts, apparently simple, to adapt and modify it. An entirely singular image of the obese person thus emergesone that the growing norms for getting thin along with the ill-understood difficulty to respect them drives toward a singular hardship.16 The latest new feature is that this hardship can express itself most easily in a society that favors intimate confession and psychologizing. The history of fat people is first the history of a condemnation and its transformations across differing cultural contexts and socially targeted rejects. It is also the history of the particular difficulties experienced by the obese person: a hardship that has probably been accentuated by the refinement of norms and the growing attention to psychological suffering. Finally it is the history of a body that undergoes modifications that society rejects and that the will is not always able to modify.

Вам также может понравиться

- KOLAKOWSKI, Leszek - Modernity On Endless Trial (Article)Документ6 страницKOLAKOWSKI, Leszek - Modernity On Endless Trial (Article)Joe-Black100% (1)

- Seductio Ad Absurdum: The Principles & Practices of Seduction, A Beginner's HandbookОт EverandSeductio Ad Absurdum: The Principles & Practices of Seduction, A Beginner's HandbookОценок пока нет

- The Pivot of Civilization (1950)Документ297 страницThe Pivot of Civilization (1950)DebajionОценок пока нет

- Culture and Restraint 1910 Hugh BlackДокумент362 страницыCulture and Restraint 1910 Hugh BlackrwinermdОценок пока нет

- The Only Heritage We HaveДокумент26 страницThe Only Heritage We Havekalligrapher100% (1)

- Sex Popular Beliefs and Culture 2011 PDFДокумент21 страницаSex Popular Beliefs and Culture 2011 PDFVelveretОценок пока нет

- Claude Levi Strauss. Race HistoryДокумент64 страницыClaude Levi Strauss. Race HistoryAntroVirtualОценок пока нет

- Siedentop Inventing The Individual PSPPEdit 2014Документ18 страницSiedentop Inventing The Individual PSPPEdit 2014mojtabajokar1382Оценок пока нет

- Saint John Chrysostom, His Life and Times: A sketch of the church and the empire in the fourth centuryОт EverandSaint John Chrysostom, His Life and Times: A sketch of the church and the empire in the fourth centuryОценок пока нет

- New Text DocumentДокумент5 страницNew Text DocumentTolgaОценок пока нет

- Racial Domination, Racial Progress: The Sociology of Race, Chapter 2Документ54 страницыRacial Domination, Racial Progress: The Sociology of Race, Chapter 2Sarah RuemenappОценок пока нет

- The Pivot of Civilization by Sanger, Margaret, 1883-1966Документ84 страницыThe Pivot of Civilization by Sanger, Margaret, 1883-1966Gutenberg.org100% (2)

- Shils 53 Meaning CoronationДокумент19 страницShils 53 Meaning CoronationThorn KrayОценок пока нет

- Rise and Fall: A Discourse Upon the Phenomena of Civilisation and DeclineОт EverandRise and Fall: A Discourse Upon the Phenomena of Civilisation and DeclineОценок пока нет

- A DawnДокумент36 страницA DawnOlanrewaju OlaniyiОценок пока нет

- Winds of DoctrineStudies in Contemporary Opinion by Santayana, George, 1863-1952Документ82 страницыWinds of DoctrineStudies in Contemporary Opinion by Santayana, George, 1863-1952Gutenberg.orgОценок пока нет

- The Ancient City - Imperium Press: A Study on the Religion, Laws, and Institutions of Greece and RomeОт EverandThe Ancient City - Imperium Press: A Study on the Religion, Laws, and Institutions of Greece and RomeРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Justice at Salem Reexamining The Witch Trials!!!!Документ140 страницJustice at Salem Reexamining The Witch Trials!!!!miarym1980Оценок пока нет

- The Ethics of Diet: A Catena of Authorities Deprecatory of the Practice of Flesh EatingОт EverandThe Ethics of Diet: A Catena of Authorities Deprecatory of the Practice of Flesh EatingОценок пока нет

- Three Lives of Golden Age BodybuildersДокумент92 страницыThree Lives of Golden Age BodybuildersDomingo MartínezОценок пока нет

- William Ophuls - Immoderate Greatness Why Civilizations Fail-CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (2012)Документ114 страницWilliam Ophuls - Immoderate Greatness Why Civilizations Fail-CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (2012)Naima LeeОценок пока нет

- Queering The Cross: The Politics of Redemption and The External DebtДокумент14 страницQueering The Cross: The Politics of Redemption and The External Debtthemsc190100% (1)

- Aspectos Psicologicos de La ObesidadДокумент14 страницAspectos Psicologicos de La ObesidadNicolás CanalesОценок пока нет

- Jonathan Swift: Gulliver's Travels: The Modern Revolution and English Literary HistoryДокумент15 страницJonathan Swift: Gulliver's Travels: The Modern Revolution and English Literary HistoryFaisal R. RabbaniОценок пока нет

- Perception of Reality and the Fate of a Civilization: Ordinary People as Virtual Pioneers in Critical TimesОт EverandPerception of Reality and the Fate of a Civilization: Ordinary People as Virtual Pioneers in Critical TimesОценок пока нет

- Paper 2Документ7 страницPaper 2Harpreet SinghОценок пока нет

- Just A Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common GoodОт EverandJust A Little Bit More: The Culture of Excess and the Fate of the Common GoodОценок пока нет

- Broken Cross - The Hidden Hand in The VaticanДокумент146 страницBroken Cross - The Hidden Hand in The VaticanOnan OnanonanОценок пока нет

- Kristol - When Virtue Loses All Her LovelinessДокумент13 страницKristol - When Virtue Loses All Her LovelinessRegina Fola OkusanyaОценок пока нет

- On Some Ancient Battle-Fields in Lancashire: And Their Historical, Legendary, and Aesthetic AssociationsОт EverandOn Some Ancient Battle-Fields in Lancashire: And Their Historical, Legendary, and Aesthetic AssociationsОценок пока нет

- Blavatsky On Progress and CultureДокумент13 страницBlavatsky On Progress and CultureMariusОценок пока нет

- The Saint As Exemplar in Late Antiquity PDFДокумент26 страницThe Saint As Exemplar in Late Antiquity PDFMilos HajdukovicОценок пока нет

- "If A, Then B: How The World Discovered Logic," by Michael Shenefelt and Heidi WhiteДокумент10 страниц"If A, Then B: How The World Discovered Logic," by Michael Shenefelt and Heidi WhiteColumbia University Press100% (1)

- Human Trafficking Around The World: Hidden in Plain Sight, by Stephanie Hepburn and Rita J. SimonДокумент17 страницHuman Trafficking Around The World: Hidden in Plain Sight, by Stephanie Hepburn and Rita J. SimonColumbia University Press100% (1)

- "Philosophical Temperaments: From Plato To Foucault," by Peter SloterdijkДокумент14 страниц"Philosophical Temperaments: From Plato To Foucault," by Peter SloterdijkColumbia University Press100% (2)

- Art On Trial: Art Therapy in Capital Murder Cases, by David GussakДокумент13 страницArt On Trial: Art Therapy in Capital Murder Cases, by David GussakColumbia University Press100% (1)

- The Best Business Writing 2013Документ7 страницThe Best Business Writing 2013Columbia University PressОценок пока нет

- Smart Machines: IBM's Watson and The Era of Cognitive ComputingДокумент22 страницыSmart Machines: IBM's Watson and The Era of Cognitive ComputingColumbia University PressОценок пока нет

- Reflections on Old Age: A Study in Christian HumanismОт EverandReflections on Old Age: A Study in Christian HumanismОценок пока нет

- The Therapist in Mourning: From The Faraway Nearby - ExcerptДокумент13 страницThe Therapist in Mourning: From The Faraway Nearby - ExcerptColumbia University Press100% (1)

- The Expansion of England: (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): Two Courses of LecturesОт EverandThe Expansion of England: (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): Two Courses of LecturesРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (2)

- Self and Emotional Life: Philosophy, Psychoanalysis, and Neuroscience, by Adrian Johnston and Catherine MalabouДокумент10 страницSelf and Emotional Life: Philosophy, Psychoanalysis, and Neuroscience, by Adrian Johnston and Catherine MalabouColumbia University PressОценок пока нет

- The Robin Hood Rules For Smart GivingДокумент17 страницThe Robin Hood Rules For Smart GivingColumbia University PressОценок пока нет

- Animal Oppression and Human Violence: Domesecration, Capitalism, and Global Conflict, by David A. NibertДокумент8 страницAnimal Oppression and Human Violence: Domesecration, Capitalism, and Global Conflict, by David A. NibertColumbia University Press100% (2)

- Emmanuel Goldstein's The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism: excerpt from the book 1984 by George OrwellОт EverandEmmanuel Goldstein's The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism: excerpt from the book 1984 by George OrwellОценок пока нет

- Mothers in AcademiaДокумент15 страницMothers in AcademiaColumbia University Press100% (1)

- Animal Oppression and Human Violence: Domesecration, Capitalism, and Global Conflict, by David A. NibertДокумент8 страницAnimal Oppression and Human Violence: Domesecration, Capitalism, and Global Conflict, by David A. NibertColumbia University Press100% (2)

- "New Welfarism, Veganism, and Capitalism," From Animal Oppression and Human Violence, by David A. NibertДокумент14 страниц"New Welfarism, Veganism, and Capitalism," From Animal Oppression and Human Violence, by David A. NibertColumbia University PressОценок пока нет

- Tibetan History As Myth, From The Tibetan History ReaderДокумент23 страницыTibetan History As Myth, From The Tibetan History ReaderColumbia University Press50% (2)

- To Carl Schmitt: Letters and ReflectionsДокумент13 страницTo Carl Schmitt: Letters and ReflectionsColumbia University Press67% (3)

- Rising Seas: Past, Present, FutureДокумент4 страницыRising Seas: Past, Present, FutureColumbia University PressОценок пока нет

- The Dalai Lamas and The Origins of Reincarnate Lamas, From The Tibetan History ReaderДокумент14 страницThe Dalai Lamas and The Origins of Reincarnate Lamas, From The Tibetan History ReaderColumbia University Press100% (1)

- The Epic of King Gesar, Excerpted From Sources of Tibetan TraditionДокумент11 страницThe Epic of King Gesar, Excerpted From Sources of Tibetan TraditionColumbia University Press83% (6)

- Double Agents: Espionage, Literature, and Liminal CitizensДокумент11 страницDouble Agents: Espionage, Literature, and Liminal CitizensColumbia University Press100% (2)

- Haruki Murakami On "The Great Gatsby"Документ9 страницHaruki Murakami On "The Great Gatsby"Columbia University Press75% (4)

- Fossil Mammals of AsiaДокумент27 страницFossil Mammals of AsiaColumbia University Press100% (6)

- Sources of Tibetan Tradition - Timeline of Tibetan HistoryДокумент10 страницSources of Tibetan Tradition - Timeline of Tibetan HistoryColumbia University Press75% (4)

- Animal Oppression and Human Violence, by David A. NibertДокумент19 страницAnimal Oppression and Human Violence, by David A. NibertColumbia University PressОценок пока нет

- What I Learned Losing A Million DollarsДокумент12 страницWhat I Learned Losing A Million DollarsColumbia University Press45% (20)

- "Animals and The Limits of Postmodernism," by Gary SteinerДокумент6 страниц"Animals and The Limits of Postmodernism," by Gary SteinerColumbia University PressОценок пока нет

- Hollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939Документ28 страницHollywood and Hitler, 1933-1939Columbia University Press100% (4)

- Picturing PowerДокумент37 страницPicturing PowerColumbia University Press100% (1)

- The Quest For Security, Edited by Joseph Stiglit and Mary KaldorДокумент17 страницThe Quest For Security, Edited by Joseph Stiglit and Mary KaldorColumbia University PressОценок пока нет

- The Birth of Chinese FeminismДокумент23 страницыThe Birth of Chinese FeminismColumbia University Press100% (1)

- The Contemporary World (An Introduction) : By: Diana Veronica T. Buot-MontejoДокумент42 страницыThe Contemporary World (An Introduction) : By: Diana Veronica T. Buot-Montejokc claude trinidadОценок пока нет

- Trash of The Count's Family - 04Документ288 страницTrash of The Count's Family - 04Yeet CodyОценок пока нет

- Myth As Determinant of NarrativesДокумент9 страницMyth As Determinant of NarrativesafaceanОценок пока нет

- 09 - Chapter III - Pinjar A Saga of Partition Pain PDFДокумент45 страниц09 - Chapter III - Pinjar A Saga of Partition Pain PDFnitya saxena0% (1)

- ARTHUR - Early Greece: The Origins of The Western Attitude Towards WomenДокумент53 страницыARTHUR - Early Greece: The Origins of The Western Attitude Towards WomenCamila BelelliОценок пока нет

- Celebrity and Political Psychology: Remembering Lennon: Anthony ElliottДокумент20 страницCelebrity and Political Psychology: Remembering Lennon: Anthony ElliottmaxpireОценок пока нет

- Knowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions, and Practices of The Kapampangan Towards Their BodyДокумент18 страницKnowledge, Attitudes, Perceptions, and Practices of The Kapampangan Towards Their BodyAriana YuteОценок пока нет

- Ndwandwe and The NgoniДокумент9 страницNdwandwe and The NgoniAlinane 'Naphi' Ligoya0% (1)

- How Does An Organization Accurately Identify The Elements of Its Own CultureДокумент2 страницыHow Does An Organization Accurately Identify The Elements of Its Own CultureDjahan Rana100% (5)

- People Who Make A DifferenceДокумент4 страницыPeople Who Make A DifferenceRqdrl JairoОценок пока нет

- IQ Test. No Obligations, Free Online IQ Test atДокумент1 страницаIQ Test. No Obligations, Free Online IQ Test atJafar SadekОценок пока нет

- CLA204H1 - Lecture 1Документ4 страницыCLA204H1 - Lecture 1scientia88Оценок пока нет

- Pnina Granirer: The Whisper of StonesДокумент37 страницPnina Granirer: The Whisper of StonesPnina GranirerОценок пока нет

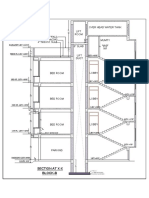

- Block-B Section at X-X: Over Head Water Tank Lift RoomДокумент1 страницаBlock-B Section at X-X: Over Head Water Tank Lift RoomchetanОценок пока нет

- Sewell DecisionДокумент6 страницSewell DecisionThe GuardianОценок пока нет

- The Church ImpotentДокумент39 страницThe Church Impotentsovereignone0% (1)

- IlceДокумент268 страницIlceelestefanya_71229617Оценок пока нет

- Meaning Making and Resilience Case Studies of A Multifaceted ProcessДокумент10 страницMeaning Making and Resilience Case Studies of A Multifaceted ProcessCarmen NelОценок пока нет

- Advanced PharmacognosyДокумент12 страницAdvanced PharmacognosyJafrineОценок пока нет

- Korean for Female Immigrants 1 - 여성결혼이민자와 함께하는 한국어1 - PDFДокумент239 страницKorean for Female Immigrants 1 - 여성결혼이민자와 함께하는 한국어1 - PDFItzel OrtegaОценок пока нет

- The Afrocubanista Poetry of Nicolás Guillén and Ángel Rama's Concept of Transculturation - Miguel Arnedo-GomézДокумент18 страницThe Afrocubanista Poetry of Nicolás Guillén and Ángel Rama's Concept of Transculturation - Miguel Arnedo-GomézanmasurОценок пока нет

- Public Culture-2015-Jørgensen-557-78 Why Look at Cabin PornДокумент23 страницыPublic Culture-2015-Jørgensen-557-78 Why Look at Cabin PorncourtneyОценок пока нет

- VGatДокумент4 страницыVGaticen00bОценок пока нет

- Aspects of Cultural History Conceptual ClarificationsДокумент4 страницыAspects of Cultural History Conceptual Clarificationsiyaomolere oloruntobaОценок пока нет

- Introduction of TONGIL Industries Company Co., LTD (Public)Документ32 страницыIntroduction of TONGIL Industries Company Co., LTD (Public)matthew_k_koh0% (1)

- UN Interview Guide PDFДокумент221 страницаUN Interview Guide PDFwpdilОценок пока нет

- SannyboyДокумент35 страницSannyboyJeffersonCaasiОценок пока нет

- INCENSE - The Encyclopedia of Ancient HiДокумент3 страницыINCENSE - The Encyclopedia of Ancient HiΑΛΕΞΑΝΔΡΟΣ ΜΠΑΡΜΠΑΣ100% (1)

- Taino Indians - Settlements of The CaribbeanДокумент8 страницTaino Indians - Settlements of The CaribbeanJulian Williams©™100% (1)

- The Diversity of The Chechn CultureДокумент262 страницыThe Diversity of The Chechn Culturetariq yosefОценок пока нет

- The Beck Diet Solution Weight Loss Workbook: The 6-Week Plan to Train Your Brain to Think Like a Thin PersonОт EverandThe Beck Diet Solution Weight Loss Workbook: The 6-Week Plan to Train Your Brain to Think Like a Thin PersonРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (33)

- Metabolism Revolution: Lose 14 Pounds in 14 Days and Keep It Off for LifeОт EverandMetabolism Revolution: Lose 14 Pounds in 14 Days and Keep It Off for LifeОценок пока нет

- How Not to Die by Michael Greger MD, Gene Stone - Book Summary: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse DiseaseОт EverandHow Not to Die by Michael Greger MD, Gene Stone - Book Summary: Discover the Foods Scientifically Proven to Prevent and Reverse DiseaseРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (83)

- The Stark Naked 21-Day Metabolic Reset: Effortless Weight Loss, Rejuvenating Sleep, Limitless Energy, More MojoОт EverandThe Stark Naked 21-Day Metabolic Reset: Effortless Weight Loss, Rejuvenating Sleep, Limitless Energy, More MojoОценок пока нет

- The Diabetes Code: Prevent and Reverse Type 2 Diabetes NaturallyОт EverandThe Diabetes Code: Prevent and Reverse Type 2 Diabetes NaturallyРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (2)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossОт EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (6)

- Instant Loss On a Budget: Super-Affordable Recipes for the Health-Conscious CookОт EverandInstant Loss On a Budget: Super-Affordable Recipes for the Health-Conscious CookРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2)

- The Diet Trap Solution: Train Your Brain to Lose Weight and Keep It Off for GoodОт EverandThe Diet Trap Solution: Train Your Brain to Lose Weight and Keep It Off for GoodОценок пока нет

- Glucose Revolution: The Life-Changing Power of Balancing Your Blood SugarОт EverandGlucose Revolution: The Life-Changing Power of Balancing Your Blood SugarРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (351)

- Secrets From the Eating Lab: The Science of Weight Loss, the Myth of Willpower, and Why You Should Never Diet AgainОт EverandSecrets From the Eating Lab: The Science of Weight Loss, the Myth of Willpower, and Why You Should Never Diet AgainРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (38)

- Body Love Every Day: Choose Your Life-Changing 21-Day Path to Food FreedomОт EverandBody Love Every Day: Choose Your Life-Changing 21-Day Path to Food FreedomРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- Keto Friendly Recipes: Easy Keto For Busy PeopleОт EverandKeto Friendly Recipes: Easy Keto For Busy PeopleРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2)

- The Volumetrics Eating Plan: Techniques and Recipes for Feeling Full on Fewer CaloriesОт EverandThe Volumetrics Eating Plan: Techniques and Recipes for Feeling Full on Fewer CaloriesОценок пока нет

- The Whole Body Reset: Your Weight-Loss Plan for a Flat Belly, Optimum Health & a Body You'll Love at Midlife and BeyondОт EverandThe Whole Body Reset: Your Weight-Loss Plan for a Flat Belly, Optimum Health & a Body You'll Love at Midlife and BeyondРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (28)

- Eat Complete: The 21 Nutrients That Fuel Brainpower, Boost Weight Loss, and Transform Your HealthОт EverandEat Complete: The 21 Nutrients That Fuel Brainpower, Boost Weight Loss, and Transform Your HealthРейтинг: 2 из 5 звезд2/5 (1)

- Ultrametabolism: The Simple Plan for Automatic Weight LossОт EverandUltrametabolism: The Simple Plan for Automatic Weight LossРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (28)

- Proteinaholic: How Our Obsession with Meat Is Killing Us and What We Can Do About ItОт EverandProteinaholic: How Our Obsession with Meat Is Killing Us and What We Can Do About ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (19)

- The Raw Food Detox Diet: The Five-Step Plan for Vibrant Health and Maximum Weight LossОт EverandThe Raw Food Detox Diet: The Five-Step Plan for Vibrant Health and Maximum Weight LossРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (22)

- Foods That Cause You to Lose Weight: The Negative Calorie EffectОт EverandFoods That Cause You to Lose Weight: The Negative Calorie EffectРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (5)

- The Complete Guide to Fasting: Heal Your Body Through Intermittent, Alternate-Day, and Extended FastingОт EverandThe Complete Guide to Fasting: Heal Your Body Through Intermittent, Alternate-Day, and Extended FastingОценок пока нет

- Glucose Goddess Method: A 4-Week Guide to Cutting Cravings, Getting Your Energy Back, and Feeling AmazingОт EverandGlucose Goddess Method: A 4-Week Guide to Cutting Cravings, Getting Your Energy Back, and Feeling AmazingРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (61)