Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Art61 Pages1-4

Загружено:

api-243165720Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Art61 Pages1-4

Загружено:

api-243165720Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

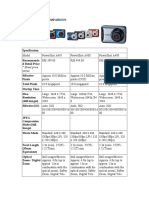

Lesson 2: Equipment: Camera Basics the Digital Camera

Introduction This lesson will discuss both film and digital cameras. You will need to understand how both types of cameras work. You will want to pay particular attention to information about the type of camera you will be using to complete your class assignments. Learning Outcomes: 1. Explain the function of various parts of film and digital cameras: body, viewer, lens, shutter, aperture, and picture data storage. 2. Use shutter speed together with aperture to achieve desired degree of motion and desired depth of field in your photograph. 3. Identify the basic types of cameras and list the advantages and disadvantages of each.

Deleted: will be discussing Deleted: the Deleted: Deleted: Deleted: the Deleted: that Deleted: for the class Deleted: What You Will Learn To Do Deleted: a Deleted: (film vs digital) Deleted: in your photograph together with Deleted: aperture to achieve Deleted: Objective 1

2.1: Parts of the Camera

Explain the function of various parts of a film and digital cameras: body, viewer, lens, shutter, aperture, and picture data storage. Every camera is made differently and, to be able to use yours correctly, you should first read the owners manual for your camera. The simplest cameras are called pinhole cameras (see figure 1.1). They consist of a light-tight box to contain the film, a small hole to let the image (via light) in, and a way to stop that light from coming in (usually a finger over the hole or a piece of black tape). Your camera will have a camera body (which is a light-tight box), an aperture (an adjustable hole) to let light in, and a shutter that will stop the light from coming in. Your camera will have other features like a lens to amplify the light, a viewfinder to see what you will take a photo of, a light meter to see how much light is available to you, and a way to advance and rewind the film. This chapter will cover some of the most basic features found on manually adjustable camerasor cameras where you have the ability to change the aperture and shutter speed settings. If you have an automatic camera, or if you are looking to purchase a camera, make sure you can switch it to manual and that you can adjust your aperture and shutter speed. Insert Photo: 1-1 from the old course. Basic Parts of the Camera You will be using your camera to take photos, so it is important that you know how to use it. Your camera will probably have more features than those listed in this chapter, so dont forget to read your owners manual for the camera that you will be using. As we discuss the parts and functions of cameras in general, have your camera and manual with you so that you may locate that part or function on your specific camera and know how to use it. Camera Body As mentioned in the introduction, the most simple of cameras is the pinhole camera. The body of a pinhole camera can be made of any light-tight container that can fit film. In the classes that I teach, I have seen students make pinhole camera bodies out of oatmeal boxes, small tins, garbage cans, wooden boxes, and other light-tight containers. Your camera will be much more sophisticated than these, but in reality the camera body only needs to be a light-tight container for the film or sensors in a digital camera to work. That means that, in film cameras, once you load your film, no light should be able to get in until you want it in. Very expensive cameras have metal bodies so they wont break as easily. Less expensive cameras have bodies made of plastic. Insert New Photo Two Ways to Control the Amount of Light Entering into Your Camera You should have two settings on your camera that will allow you to change the amount of light entering your camera body and exposing your film: aperture and shutter speed. If too much light gets into your camera, your photo will be overexposed, and if too little light gets into your camera, your photo will be underexposed. If you understand how to control exposure, you will be able to take perfectly exposed

Formatted: Indent: First line: 0"

Deleted: (film vs digital) Deleted: that came with Deleted: Deleted: , Deleted: adjustable hole, Deleted: called an aperture Deleted: , Deleted: that will Comment [KW1]: I think we mean may here instead of will. Do you agree? Comment [KW2]: I deleted and/or. Does the student need to be able to adjust both, or either aperture or shutter speed? Deleted: /or Deleted: and Deleted: your own camera Deleted: than Deleted: the Deleted: which Deleted: a Deleted: these Deleted: ; Deleted: that hold mints, medicine, or cookies; Deleted: ; Deleted: ; Deleted: therefore Deleted: Deleted: make

photographs every time with the right equipment. Before you depress the shutter release on your camera you should set aperture and shutter speed to be sure your exposure is correct. Aperture One of the settings that controls exposure is called the aperture (also called the diaphragm or lens opening). The aperture controls the intensity of light that reaches your film by changing the size of the hole that lets light into your camera. Find the aperture ring or adjustment on your camera. The aperture adjustment will have numbers like f/16, f/11, f/8, and f/5.6. These numbers are known as f-stops or f/numbers. They are fractions, and so the bigger the number on the bottom, the smaller the aperture opening. For example, f/16 is a smaller opening than f/8 because 1/16 is a smaller number than 1/8. Insert New Photo Shutter Speed The other setting that controls exposure is called the shutter speed. It controls the length of exposure, or how long light will be allowed to enter the camera through the aperture. Find the shutter dial or adjustment on your camera. The shutter speed adjustment will have numbers like 1000, 500, 250, 125, and 60. These numbers are fractions of a second, therefore, 1/1000 of a second is much faster than 1/60 of a second. Insert New Photo How Do I Know What to Set My Aperture and Shutter Speed at? Light Meter Most cameras have an internal light metering system that can measure the light coming in so that you or, in the case of cameras with autoexposure (see your owners manual for autoexposures like shutter priority, aperture-priority, or full autoexposure), the camera can set the correct aperture and shutter speed to get the correct exposure. There are several types of light meters, but the type that is usually built into a camera is called a reflected light meter. It averages all the lights and darks that are reflected back to the camera from the subject, and then calculates a shutter speed and aperture combination that will produce middle gray in a print. This system will work well for most scenes, because in most cases your subjects will have equal amounts of darks and lights. However, this type of metering will have poor results in subjects that are very light or are very dark. For example, say you want to take a photo of some eggs on a light-toned tablecloth. The light meter will assume that your subject has a balance of lights and darks and since it does not, your settings will be incorrect. If you were to meter bell peppers on black velvet, your light meter would again give you incorrect settings. Instead of white eggs in the first example, you would have middle-gray toned eggs (see figure 1.6), and your peppers on black velvet would appear middle-gray in the final print if you were to use the settings given by your light meter (see figure 1.5). When you meter a scene that you believe will give you false settings, you have several options. You can use a neutral gray test carda middle-gray piece of paper you can buy at a photography storeby holding it up in front of the scene you wish to shoot and meter on the card instead. Dark skin is about the same tone as the neutral gray test card and average light-toned skin is one stop (explanation below) lighter. Meter on your hand by holding it up in front of the scene to be metered, you may need to get closer to the subject to make sure your hand has the same lighting conditions as the scene and then back up to take the photo. If your skin is dark, then no adjustments need to be made. If your skin is light-toned, then add one stop of light. One stop of light is created by either opening up the aperture by one whole stop, i.e., f/16 to f/11, or by doubling the shutter speed time, i.e., 1/500 of a second to 1/250 of a second. If your skin is extremely light, then you may need to open up two full stops. Other hard-to-meter scenes include a subject with a very light background, like a bright sky. In this case, meter on the subject only, rather than the subject and background together. By doing this you will prevent your subject from showing up as only a silhouette. Insert New Photos The Steps to Metering Load your camera with film according to the instructions in your owners manual.

Deleted: these two settings ( Deleted: ) Deleted: a.k.a.

Deleted: how long Deleted: of light Deleted: through the aperture,

Deleted: / or Deleted: s Deleted: you desire to photograph

Deleted: Deleted:

Set your ASA/ISO film speed indicator (see figure 1.7) to the type of film you are using (see lesson on film for suggestions). Insert New Photo Set the camera to the desired exposure mode, that is, manual exposure (you set both shutter speed and aperture), shutter-priority (you set the shutter speed and the camera will set the correct aperture), aperture-priority (you set aperture and the camera will set the correct shutter speed), or programmed automatic exposure (the camera will set both the correct aperture and shutter speed) . Note that your camera may only have manual exposure available or any combination of the aforementioned exposure modes. Meter your scene by looking through the viewfinder and activating the meter (see your owners manual on how to activate your meter). If your camera has no light meter, you can refer to the suggested aperture and shutter speed settings that are usually found on the inside carton of the film packaging. Determine if your scene has a balance of lights and darks or grays. If not, then meter on a gray card or use your hand as described above. In the case of a very bright background, meter on the subject only by getting closer to the subject, metering, setting your exposure at that location, and then returning to your original location. Set the aperture and shutter speed for correct exposure and depress the shutter release. Note: Usually, a tripod is used for exposures longer than 1/60 of a second, using a normal focal length lens, to reduce blur caused by motion. Do I Have More Choices Than the One that My Light Meter Tells Me? Since the aperture and shutter speed both control the amount of light that enters into the camera, once you know a combination of the two that will give you a correct exposure, you can change one setting as long as you change the other the opposite way. This is known as The Law of Reciprocity (see figure 1.8). We have two controllers of light on the camera, the aperture and the shutter speed. If I open up the aperture one stop, say, from f/8 to f/5.6, what I am doing is letting twice the amount of light (in intensity) into the camera. If I close down the shutter speed from 1/60 of a second to 1/125 of a second, I am letting half the amount of light in (in time). Therefore, if my light meter shows that I will get a correct exposure if I set my aperture at f/8 and my shutter speed to 1/60, I can also use a setting of f/5.6 and 1/125 because both exposures are equivalent. The amount of light entering the camera is the same even though the settings may be different. Insert New Photo Why Would I Ever Want to Change My Settings Using the Law of Reciprocity? You will want to have flexibility. In some lighting conditions and with some lenses, one combination of settings given by the light meter may not be available. Alternate settings allow you to have options while still having the correct exposure. In 2.2 you will learn that besides controlling exposure, aperture also controls depth of field, and shutter speed controls subject movement. Lens Insert New Photo Basically, all camera lenses do the same thing: they collect light from an image and project it onto film. However, by controlling the focal length (the distance from the optical center of the lens to the focal plane when the lens is focused on infinity) of the lens (usually this technical stuff can be described as the length of the lens), the photographer can control magnification, and angle of view (or the amount of the scene that will show up on the film) (see figure 1.10). Lenses can be automatic focusing or manual focusing depending on the type of camera and options available for it. Insert New Photo Lenses can be divided into the following five basic types: Normal Lenses

Deleted: Comment [KW3]: To which lesson is this referring?

Deleted: i.e.,

Deleted: Deleted: ,

Deleted:

Deleted: objective 2

Deleted: Comment [KW4]: This paragraph is a little confusing because of the number of parenthetical statements.

Also called a standard lens, this is the type that you will probably use the most, especially in beginning photography. For a 35mm film camera, a normal focal length lens is 50mm. A 50mm lens on a 35mm film camera will approximate the vision of the human eye. It sees the world about how you see it. Telephoto Lenses These lenses have focal lengths that are longer than the normal lens. Common telephoto focal length lenses for a 35mm film camera include 85mm, 105mm (often used as a head-and-shoulders portrait lens), 135mm, 200mm, 300mm, 400mm, 500mm, 600mm, 1000mm, and 1200mm. The longer the focal length of a telephoto lens, the greater the magnification, but the narrower the angle of view. That means that far away objects will appear closer (telephoto lenses are great to photograph sports and wildlife) but some of the scene will be cropped out of the photo. Telephoto lenses reduce the differences in the size of objects that are in the foreground and the background, this effect is known as telephoto compression. This means that objects in the foreground appear to be closer to the background than they really are. Some drawbacks to consider before purchasing a telephoto lens are that telephoto lenses tend to be bulkier and more expensive than normal lenses. Focusing must be made more accurately with a telephoto lens because they create a shallower depth of field than a normal lens. They are usually slower than normal lenses. Speed, when discussing lenses, refers to the widest aperture opening capable for that lens. Telephoto lenses allow less light through them, requiring longer shutter speed times than normal lenses, unless you pay more money for a faster lens. Telephoto lenses also magnify movement and a tripod is useful to stop blurred movement caused by the photographer. Wide-Angle Lenses These lenses have focal lengths that are shorter than normal lenses. Some common wide-angle lenses used in 35mm film photography include 35mm, 28mm, 24mm, 20mm, and the fish-eye lenses under 20mm in length that produce distorted images. These short focal length lenses produce images that capture a wide angle of view and tend to push the foreground further from the background, adding depth and perspective. Wide-angle lenses create photographs that have more depth of field, which can allow the photographer more room for error when focusing. In fact, some fish eyes cant even be focused because they have such a great depth of field that everything from as close as touching the lens to infinity will be in focus. However, for good or bad, these lenses create a great deal of distortion. Wide-angle lenses are great for panoramas, in tight quarters, and where distortion is required. A fish eye can be useful for special effects. Zoom Lenses These lenses do not have a fixed focal length. A zoom lens that can be adjusted from 35mm to 105mm is like owning a 35mm lens, a 105mm lens, and all the lenses in between. This can save the photographer money, but zoom lenses do have their disadvantages. Zoom lenses tend to be even bulkier and slower than their fixed focal length equivalent, and are generally not as sharp. Macro Lens These lenses are often found as a mode on a zoom lens. They are used for close-up photography. Viewfinder A photographer usually uses the viewfinder as a format to compose her photograph. This composing of the photograph should be considered before releasing the shutter, (see the lesson on composition for more information on composing your photograph). Insert New Photo You will use your viewfinder to help you focus on the most important part of the scene. Some common focusing aids on single lens reflex cameras include ground glass focusing (an etched glass screen on which the image can be focused), micro-prism (a circle that appears coarsely dotted until focused), and split-image focusing (that offsets the subject until it is focused). You will find a rangefinder system focusing system on a rangefinder camera (see 2.3 for information on the rangefinder) that operates by superimposing two images of the same subject. The lens is focused sharply on the subject when the two images appear exactly superimposed.

Deleted: are under 20mm in focal length

Deleted: and yet

Comment [KW5]: Should this just say something to the effect of, we will learn about composition in lesson __.? Deleted: to be in sharp focus

Deleted: objective 3 Deleted: in this lesson

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Switch Off Camera to Save BatteryДокумент22 страницыSwitch Off Camera to Save BatteryFelipe Chimicatti100% (1)

- Panasonic Lumix LX5Документ269 страницPanasonic Lumix LX5Jeffrey TamОценок пока нет

- Germanhandwritingch 1Документ9 страницGermanhandwritingch 1api-243165720Оценок пока нет

- Bookchapter FinalforportfolioДокумент11 страницBookchapter Finalforportfolioapi-243165720Оценок пока нет

- Resume Kaylaswan December2013 2Документ1 страницаResume Kaylaswan December2013 2api-243165720Оценок пока нет

- Guitr-041-200 Pages1-29Документ29 страницGuitr-041-200 Pages1-29api-243165720Оценок пока нет

- Pages From Ahtg-100-201Документ20 страницPages From Ahtg-100-201api-243165720Оценок пока нет

- Mackay c00 Introduction Pages1-3Документ3 страницыMackay c00 Introduction Pages1-3api-243165720Оценок пока нет

- Hist 221 Pages1-4Документ4 страницыHist 221 Pages1-4api-243165720Оценок пока нет

- Mcfarland Final c02 Leitichs America Pages6-10Документ5 страницMcfarland Final c02 Leitichs America Pages6-10api-243165720Оценок пока нет

- Autofocusing System With Fuzzy Logic ApplicationДокумент27 страницAutofocusing System With Fuzzy Logic ApplicationademОценок пока нет

- Helios 44 Outer LimitsДокумент17 страницHelios 44 Outer LimitsgabionsОценок пока нет

- 2013 Bower Catalogue HD PDFДокумент38 страниц2013 Bower Catalogue HD PDFAndrés Mora MirandaОценок пока нет

- Learn More E - Commerce Product Photography TipsДокумент9 страницLearn More E - Commerce Product Photography TipsClipping Path ClientОценок пока нет

- GH5 Pro Settings Cheat Sheet 1Документ9 страницGH5 Pro Settings Cheat Sheet 1Prince YoungОценок пока нет

- Leica ManualДокумент598 страницLeica ManualAlonso Chacon100% (2)

- Aperture: Shutter SpeedДокумент3 страницыAperture: Shutter SpeedTanvirОценок пока нет

- Street Price VariesДокумент7 страницStreet Price VariesLee Mun HowОценок пока нет

- Olympus 35rcДокумент38 страницOlympus 35rcalexОценок пока нет

- SZOMK-wall Mounting Plastic Enclosure Series CatalogueДокумент8 страницSZOMK-wall Mounting Plastic Enclosure Series CatalogueRing Balázs0% (1)

- Amateur Photographer - 15 August 2015Документ84 страницыAmateur Photographer - 15 August 2015lasgpoaОценок пока нет

- Makro Symmar - 5.6 120 0.5xДокумент3 страницыMakro Symmar - 5.6 120 0.5xwilco23Оценок пока нет

- Photojournalism PressДокумент60 страницPhotojournalism PressMary Ann Ayson100% (1)

- Penawaran Harga Pembuatan Video Profil Dinas Pertanahan Provinsi Sulawesi TengahДокумент5 страницPenawaran Harga Pembuatan Video Profil Dinas Pertanahan Provinsi Sulawesi TengahJulian CesarОценок пока нет

- Forensic Photography Techniques and ApplicationsДокумент108 страницForensic Photography Techniques and ApplicationsJoel Barotella0% (1)

- Session 99Документ1 страницаSession 99foliageОценок пока нет

- Holga ManualДокумент20 страницHolga ManualRoXana SellaОценок пока нет

- RC AKIC NEW FORENSIC PHOTO May SagotДокумент69 страницRC AKIC NEW FORENSIC PHOTO May SagotHizam CorobongОценок пока нет

- Forensic Photography GuideДокумент7 страницForensic Photography GuideMagr Esca100% (5)

- Types of Camera AnglesДокумент2 страницыTypes of Camera AnglesMaJudith JavilloОценок пока нет

- Kobre - Combining Audio and StillsДокумент15 страницKobre - Combining Audio and StillsSandra SendinganОценок пока нет

- Photographing Flowers With A Macro Lens: PhotzyДокумент22 страницыPhotographing Flowers With A Macro Lens: PhotzyEmilОценок пока нет

- E18 Repair Guide - How To Repair A Canon E18 Error (Lens Problem)Документ2 страницыE18 Repair Guide - How To Repair A Canon E18 Error (Lens Problem)macfunzОценок пока нет

- Sony HandyCam SpecificationДокумент3 страницыSony HandyCam SpecificationYibie NewОценок пока нет

- CinematographyДокумент51 страницаCinematographypranavОценок пока нет

- Kirkwood Community College Fall 2016 Photography CoursesДокумент3 страницыKirkwood Community College Fall 2016 Photography CoursesGreg JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Ol Xd2000sz PDFДокумент2 страницыOl Xd2000sz PDFPatrickОценок пока нет