Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Prologue Magazine - Patrolling The Coastline On Wheels

Загружено:

Prologue MagazineОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Prologue Magazine - Patrolling The Coastline On Wheels

Загружено:

Prologue MagazineАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Patrolling the Coastline on Wheels

U.S. Coast Guard Used Motorcycles to Watch Beaches During World War I

By William R. Wells II

merican soldiers were now on the battlefields of Massachusetts, was part of an experiment during World

A Europe, and Edward Forbes was patrolling Florida

beaches for any signs of the arrival of German soldiers,

War I by the Coast Guard to fulfill one of its missions of

guarding the nation’s coast.

sailors, or spies on American shores during October 1917. There had been concern that Germans might try to bring

To help him do his job, the Coast Guard had provided him the war to America’s shores, and the revelation of the famous

with a motorcycle—to patrol more areas quickly and to return Zimmerman telegram—in which the Germans sought to

to his post with news of any sightings as fast as possible. bring Mexico into the war against the United States—had

This day, however, he was caught by the surf and left the fueled fears of invasion and prompted patrols along the

motorcycle on the beach after he couldn’t get it started before nation’s Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

the rise of the tide. The next day, he was able to pull it out Motorcycles had been requested for patrols on Florida’s

and spent the next four days cleaning it up—removing rust east coast and the Texas coast along the Gulf of Mexico.

from the brightwork and getting the ignition back in work- They were to be part of America’s arsenal in what would be

ing condition. But the clutch was frozen as well, and that called the World War.

took another day to disassemble, clean, and reassemble.

This was not a good beginning for a war patrol, nor would

Above: W. C. Leaird’s bicycle shop in Fort Lauderdale, ca. 1916, where

it get any better. In the meantime, those on foot patrol contin- repairs were made on some Coast Guard motorcycles. Surfman

ued their five-mile round trip patrols on the beach. Wallace King (left) was part owner. The Coast Guard purchased 12

Forbes’s use of the Indian motorcycle, manufactured by motorcycles for stations along the Florida coast and one for the Point

the Hendee Manufacturing Company of Springfield, Isabel, Texas, station.

40 Prologue Fall 2009

• • • • • • • • •

Putting the nation on a war footing on April 6, 1917,

President Woodrow Wilson had moved the Coast Guard

under the command of the Department of the Navy.

As part of that move, a squadron of Coast Guard cutters

had sailed to Europe on convoy duty, leaving most of the

legwork of coastline surveillance responsibility to the profes-

sionals at the Life Saving Service (LSS), which had been in

existence since 1878 and had been incorporated into the

Coast Guard in 1915. The LSS routine of patrolling the

beaches on foot remained, which accounted for the large

number of stations along the U.S. coastline. Above: The “type N.E. Indian motor cycle, 1917, Powerplus Twin

Except for minor administrative reporting hierarchies, the Cylinder, cradle spring frame, three speed type with complete electri-

Navy Department left the operations of the civilian-run life- cal equipment, including ammeter” used by the Coast Guard in Florida

saving stations to their district superintendents with over- during World War I. The Coast Guard hoped this new technology

sight by a commissioned officer in Coast Guard headquar- would enable surfmen to patrol more areas quickly and to return to

their posts with news of any sightings as fast as possible.

ters. But because of its wartime duties assigned by the Navy,

the Coast Guard gave the life-saving stations along the Below: Coast Guard Captain-Commandant Ellsworth P. Bertholf agreed

coasts the additional duty of looking out for any enemy to requests for motorcycles from the Eighth District at Jacksonville,

landings of troops or spies. Stations on the east and Gulf of Florida. His June 19, 1917, letter specifies the model and the quantity

Mexico coasts had special responsibilities of real and per- for each station.

ceived threats from Germany.

The United States was virtually without an intelligence

service, and notification of German threats came from

British intelligence sources. In February 1917, the British

government, after holding the information for a month,

alerted the United States of a plan by German Foreign

Secretary Arthur Zimmerman to rally Mexican support

against the United States. Zimmerman promised the return

of former Mexican territories if Germany won the war.

The plot was made believable by Mexican revolutionary

Pancho Villa’s raids into Texas a year earlier. A month fol-

lowing notification of the Zimmerman plan, an incident

unknown to the general American public helped cement the

government’s perception of the truth of Zimmerman’s plan.

The Coast Guard Cutter Comanche, under the command

of Capt. Henry Ulke, sailed from Galveston, Texas, to inves-

tigate a rumor that U.S. citizens “were secretly building sub-

marines for a belligerent power” on Hog Island near Aransas

Pass, Texas.

Upon arrival at Hog Island, the cutter’s officers found

these supposed “fifth columnists” to be a group working for

American inventor Lemuel John Husted. The group exper-

imented in the building and testing of “an automatic steer-

ing device for torpedoes,” but the cylindrical shape of

Husted’s test models raised local suspicions. The investigat-

ing officer, Lt. William P. Wishaar, found only workmen

and workshops and reported that no explosives or even the

device were on the island.

Although not substantiated in this instance, Wishaar’s

report appeared to validate the Navy Department’s suspi-

cions of at least the possibility that a belligerent power could

build submarine bases in or near Mexico.

Patrolling the Coastline on Wheels Prologue 41

These stories of war and suspicions of port and gave the Coast Guard an opportu-

spies, saboteurs, assassins, and international nity to improve its equipment and operabil-

intrigue caused the Coast Guard and ity. Bertholf had already used the war to

Lighthouse Service to discharge all unnatu- replace many of the cutter’s obsolete

ralized German citizens in its ranks; includ- weapons systems and scheduled more for

ing several members of the cutter replacement.

Comanche’s crew. Ordering the equipment marked the first

Rumor and fear were enough, and spy and least expensive step. The motorcycles

fever gripped the nation. would need not only operators but men with

enough mechanical ability to keep them

• • • • • • • • • running. On May 19, Bertholf sent a

In March 1917, John W. Richardson, the telegram to Superintendant Richardson ask-

superintendent of the Coast Guard Eighth ing him if he knew how many men at the

District at Jacksonville, Florida, and J. W. various stations had any knowledge of

Quinan, the customs inspector at Key West, motorcycles or any mechanical ability at all.

reported “strange doings and night signaling Richardson, in turn, asked the keepers of the

. . . at various points on the east coast [of affected stations.

Florida].” No one, however, confirmed or On May 19, Keeper Charles Skogsberg

investigated the reports. The lack of investi- (Fort Lauderdale) logged in his scrupulously

Surfman Wallace King suffered the first mishap with

gation was due largely to the time required kept daily station journals, “telegram recived the new motorcycles at the Fort Lauderdale, Florida,

to get to the sighting location by foot. The [sic] from Superintendent at 6:00 P.M. nam- Coast Guard Station in February 1918 when he ran

foot patrols carried flares, but these were ing men of crew familiar with operating over a log covered with seaweed.

intended to signal the station lookout of motorcycles . . . answered at once naming

trouble. The signals were useless for military the men familiar.” Skogsberg reported

reports. Something faster was needed. Wallace King, Alonzo L. High, and John L. responded and established an infantry-styled

Introducing any new technology to the Simmons. The seven other stations queried Coastal Forces within the U.S. Coast Guard

life-saving stations was a difficult task reported 16 more men. The information Reserve. The Coast Guard resurrected this

because of their reliance on traditional meth- sent to Coast Guard headquarters was idea in the 21st century in a response to

ods, but it was made doubly problematic by encouraging; however, the plan also called international and domestic terrorism.)

the well-known frugality of the Treasury for stationing a motorcycle at unmanned The relationship between motorcycle

Department. The war, however, would locations such as the lighthouse at Jupiter patrol ideal and reality became muddled as

change station life and technology. Inlet. There, Keeper Skogsberg hired the first motorcycle arrived at Fort

To speed reporting, Richardson and Edward Forbes as the motorcycle patrol Lauderdale. However, it was not until

Quinan made a pitch to Coast Guard head- operator and mechanic. September 24, 1917, that the Coast Guard

quarters in Washington, D.C., for at least With orders placed and men hired, established its first “Special Motorcycle

one motorcycle to each of the stations on the Inspector Quinan waited but grew anxious at Patrol” at Jupiter Inlet Light House. The

east coast of Florida and the Texas coast the delay in the motorcycles’ arrival. On Fort Lauderdale station journal explains that

(from Brazos to Corpus Christi). August 20, he finally wrote to Senior Captain the boundaries of this patrol between “Lucie

Coast Guard Captain-Commandant Daniel P. Foley asking about the progress of Inlet to the north and Lake Worth to the

Ellsworth P. Bertholf agreed and on June 19, the order and the patrol. Foley responded south, about 25 miles total.” Quartered at

1917, specifically asked the Navy Department three days later that the Navy Yard at the Jupiter Inlet Light House, Surfman

to provide 13 “type N.E. Indian motor cycle, Washington, D.C., had accepted the bid pro- Forbes finally received his motorcycle from

1917, Powerplus Twin Cylinder, cradle spring posals a day or two earlier and the patrols Jacksonville on September 26 and began

frame, three speed type with complete elec- should begin as soon as the equipment arrived. assembling it.

trical equipment, including ammeter.” As an Foley had some doubts about the urgency Reminiscent to anyone who has attempt-

afterthought, remembering their wartime of Quinan’s initial claims. Foley advised that ed assembly of children’s toys, Forbes found

mission, he added “all machines to be fin- the patrols could wait because the first sight- some minor parts missing and assembly not

ished in olive drab color.” ings of “strange doings” may have been ships as easy as first thought.

In one small order, the Coast Guard took practicing at sea. The gas tank leaked, and he charged the

a large step in technology. Commandant (Similar claims surfaced in Florida follow- battery at the Jupiter Inlet Wireless Station.

Bertholf issued shipping locations for the 13 ing the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. The calls Forbes then made the 40-mile ride to West

motorcycles, 12 in Florida and one in Texas. for protection from then “subversive activity” Palm Beach for parts and further repairs at

The war brought increased budgetary sup- were frequent. In 1963, the Coast Guard W. W. Hill’s Motorcycle Shop. The next day

42 Prologue Fall 2009

to pull it out the next day and spent several Forbes’s mechanical problems continued,

days getting it back in shape. too. In a potentially dangerous operation

High water and surf were only two of the the following January, he disassembled the

motorcycle’s natural enemies. Forbes spent battery and “found plates badly warped and

part of his time walking “on the trail at so badly eaten as to be beyond repair.”

Spouting Rocks,” removing “cactus plants, Despite the mechanical and natural prob-

etc” that endangered the tires. Mechanical lems, the motorcycle operators persevered,

problems continued as the weather wors- which testifies to their willingness to try to

ened. Typical Florida fall rains shorted out make a new technology work. Then again,

the magneto and caused the closure of the this was their sole job. If the motorcycles

Hobe Sound Bridge for repairs. Then the failed, then they would have to find

storage battery died, and the engine ran out employment elsewhere.

of lubricating oil. All factors seemed to con- At Coast Guard headquarters, the ques-

spire to hamper or prevent patrols, resulting tion of motorcycle spare parts had become a

in the loss of the motorcycle for 17 days dur- matter of concern. Commandant Bertholf

ing October 1917. The next month did not wrote the Navy asking for enough spare

start with any greater promise. parts to keep the machines operating. The

On October 11, 1917, the Fort Lauderdale Navy balked at supplying the parts, but

station received its motorcycle. John Simmons Bertholf reminded the Navy Department

Senior Captain Daniel P. Foley in Washington doubt-

ed the urgent need for coastal motorcycle patrols in

was the first operator, and he too immediately that the Coast Guard had no congressional

Florida advising that the first sightings of “strange ran into mechanical problems and difficulties appropriation for passenger-carrying vehi-

doings” may have been ships practicing at sea. with Keeper Skogsberg. Simmons had to cles and that the upkeep of the motorcycles

explain to Skogsberg why he decided not to was the Navy’s responsibility. Bertholf also

take his time clock on patrol, telling the keep- asked for gasoline. His point was that

he took the motorcycle on a 200-mile test er that he thought it “probably in the way” because the motorcycles were doing Navy

ride. The motorcycle appeared to give “satis- while operating the machine. Then, as now, work and the Coast Guard was under the

faction” even though he reported the weath- the time clock was the bane of the watchman. Navy operational orders for the duration of

er to be very stormy. This was nearly the last Four days later, his motorcycle overheated, the war, the Navy had to allocate funds to

time the motorcycle functioned consistently, causing valve leakage that required a complete meet those operational requirements.

but it was a great ride. overhaul of the motor. Within a week of the Despite the motorcycle problems, other

Road use for the motorcycle appeared to repairs he, like Forbes, was forced to leave the improvements came to the life-saving sta-

be satisfactory, but actual use on the beaches motorcycle on the beach. Unlike Forbes, he tions. The war pushed the Coast Guard to

was another matter. It is not known if was able to get it above the high-tide line, but upgrade and include the stations in the

Richardson or Quinan directed anyone to evidently not far enough because the electrical organization as military members. This

make surveys of the prospective patrol areas system short-circuited from the salt water. included issuing the beach patrols small

to support the need for motorcycles, and It is unclear, but the mechanical problems arms for the first time in the history of the

despite their supervisory status, neither of these supposedly new motorcycles seemed life-saving stations. During August 1917,

appeared to know the terrain of their district indicative of used machines. Although the the stations received three Springfield 1903

very well. Three days after receipt, assembly, motorcycles were packed in crates upon .30 caliber rifles and three .38 caliber Colt

and test rides, Forbes found that he could arrival, no one ever said these were new revolvers. The following January the station

only patrol about one and one half to two machines. In previous years, Marine Corps received an additional Colt revolver for the

miles on the north leg of his patrol area, units in Haiti used the same style of motorcy- motorcycle patrol. Improved surfboats were

where “any further progress was impractical cle. It would be logical to issue reserviced also transferred from New Jersey to Florida.

on account of High Surf, washing up on the machines to the Coast Guard beach patrols The Coast Guard added a telegrapher’s

Beach, on to a Rockledge [sic].” and save the newly manufactured ones for key and wire to the list of carried equipment

Forbes then turned south and found his way more military uses. The continued mechani- that already included a revolver and the time

blocked by the surf and another rock ledge. cal problems seem to bear out this possibility. clock. The key and wire allowed the motor-

He tried his patrol again on October 2, but Simmons continued to report problems. cycle patrol to tie into the telegraph lines on

this time the surf caught him, and he left the He could not complete his November 20 the patrol route and report immediately

motorcycle on the “Beach 2 miles South of patrol because of carburetor trouble in instead of making a time-consuming return

[Lake Worth] Inlet, from breakers wetting it which the “butterfly valve [was] so badly trip to the station—an important feature

and stoping [sic] it and unable to get it start- worn [it is] impossible to get [a] satisfactory considering the growing failure rate of the

ed before the rise of the tide.” He managed slow speed adjustment.” motorcycles.

Patrolling the Coastline on Wheels Prologue 43

The Fort Lauderdale Station was supervised by

Keeper Charles Skogsberg. His log entries for

September 26, 1917, note Surfman Edward Forbes’s

receipt of his motorcycle, discovery of missing parts

and leaky gasoline tank, and transport of the vehicle

40 miles to West Palm Beach for repair.

The addition of a telegrapher’s key to the Richardson added an exception for cost about $152 each, the patrols could not

World War I patrols became the communi- Lemon City (Station No. 209), which had a be justified much longer. Except for the

cation model used by the Coast Guard beach seven-mile stone road, as well as the special motorcycles that Richardson wanted saved

patrols during World War II. During 1918, patrol at Boynton, Florida, which also used a for stone road use, he recommended the

the stations received telephones to enhance stone road for about 35 miles. In previous remainder be disposed of “to the best advan-

communications, but these telephones were months, the stations themselves sent com- tage of [the] Coast Guard.”

to be used only for emergency work. In addi- plaints that the motorcycles were useless on The war’s end was likely as great a factor

tion, each surfman received, on average, some mudflats and sand dunes. The Coast in Richardson’s decision as the deficiencies

increased pay to about 14 dollars a month. Guard station at Port Isabel, Texas, retained in the motorcycles. Once the war ended, so

Mechanical failures, bad weather, and at its motorcycle. did the Navy’s funding. In January 1919, W.

least two accidents plagued the motorcycle Richardson listed the lack of repair parts B. Furcher, commandant of the Seventh

patrols. The first accident occurred in as a leading cause for infrequent use of the Naval District, Key West, wrote Richardson

February 1918, when Surfman Wallace motorcycles. He complained that repair asking him whether or not they should

King, operating from Fort Lauderdale, parts were not available locally, and those retain any or all of the motorcycles. Giving

wrecked when he ran over a log covered with ordered from the manufacturer took from 4 Richardson a hint to the answer he wanted,

seaweed. Forbes’s accident was potentially to 12 weeks to receive. He was frustrated Furcher added, “now that hostilities have

more serious. As if in a silent film slapstick that when the parts did arrive, “some small ceased and they are no longer needed for

scene, Forbes reported that the footboard item such as an additional screw or other military purposes.”

“flopped to [an] upright position, lacking [a] similar part is needed and consequently [the] Bertholf wrote Richardson in early

brake pedal, causing him to lose control of machine is again placed out of commission February 1919, and officially ended the

machine and ran into railing [of Hobe for another month or two.” wartime motorcycle patrol on February 7,

Bridge], breaking headlight, footstep starter The motorcycles at stations Nos. 202, 1919, except for those asked for by

and Mag[neto] control.” 204, 205, 206, and 208 were out of commis- Richardson. As directed, Richardson select-

By November 1918, the enthusiasm sion for months at a time. It appeared to ed the best five motorcycles, retained all the

exhibited earlier for the motorcycles waned as Richardson (as a whole nation would ulti- spare parts, and shipped the remaining

they became more nuisance than assistance. mately learn about automotives) that the motorcycles to the Navy at Key West. Now

The general disappointment showed as older the machines became, the more repairs without the bothersome motorcycles, the

Richardson wrote now Commodore- they needed. stations resumed the prewar foot patrols of

Commandant Bertholf on November 13, Richardson estimated that 75 percent of about two and a half miles on either side of

1918: “Owing to the great expense in keeping the motorcycle fleet was out of commission the stations.

up motorcycles and unfavorable results . . . it at any one time. The cost was too high. Bertholf also informed Commandant

is recommended the motor cycle patrol at When Fort Pierce (Station No. 206) received Furcher where the motorcycles were going to

Florida East Coast Stations . . . be discontin- a second motorcycle, its repair costs rose to be stationed and that the “double patrols”

ued.” Richardson’s use of “unfavorable more than $125 for both its machines from (around-the-clock) would cease and each

results” was an admission the motorcycles June to November 1918. The motorcycle station would reduce its complement to nine

had not been as reliable or useful as hoped. used by Forbes at Hobe Sound “is beyond men. The ending of the war and motorcycle

The hopeful 1916 reviews of motorcycle use repair owing to the length of time this use forewarned the ending of another era. By

by the U.S. Marine Corps and the Spanish machine being used and the mean character November 1919 the Coast Guard reduced

Army dimmed. of the beach.” Considering the motorcycles East Florida stations Nos. 202, 203, 204,

44 Prologue Fall 2009

205, 206, 207, 208, and 209 to two surfmen there were few lessons recorded. The Coast automatically increase reliability or enhance its

each and changed their designations from Guard published no official history of its activ- mission. However, the Coast Guard learned to

life-saving stations to “Houses of Refuge.” ities during the war and left whatever experi- accept and apply technology where it would

The reduction, although part of a postwar ences in the memories of its officer corps. work and throw it off where it did not.

austerity plan, was in part perpetrated by Nevertheless, some in the Coast Guard may This pragmatic outlook helped keep

wartime improvements in technology, partic- have remembered and the exclusive use of spending in check while adhering to its

ularly in communications and motorboats, motorcycles for beach patrol was not repeated. motto—Semper Paratus (“Always Ready”). P

which made a number of stations obsolete. During World War II, the Coast Guard © 2009 by William R. Wells II

Similarly, in the mid-1990s the Coast Guard relied primarily on foot and horse patrols to

attempted to close 22 search-and-rescue defeat the “mean character” of the beaches

(life-saving) stations on the same rationale of and keep a security vigil. A group of German Author

increased technology, specifically aircraft and saboteurs was captured on Long Island dur- William R. Wells II is an author

satellite communications and navigation. ing the war because of a lone Coast and historian of the U.S. Coast

The romance of the lone surfman on beach Guardsman on foot patrol. Guard and the U.S. Revenue

patrol returned to east Florida without the The Coast Guard discovered that the intro- Cutter Service and is an adjunct

twin-cylinder Indian noise. Unfortunately, duction of technological advances did not instructor of history at Augusta State University.

NOTE ON SOURCES

Archival sources used in this article are mainly Classification 701: Complements, File 1910–1922, 1949 U. S. Naval Institute publication, The United

drawn from the Records of the U.S. Coast Guard, Entry 82A, RG 26) and provided the names of the States Coast Guard 1790–1915.

Record Group (RG) 26, at the National Archives men familiar with operation of motorcycles. The “American Motorcycles for European Fighting

in Washington, D.C., and in Atlanta, Georgia. men were Brice F. George, Station No. 202; Gray Men,” Scientific American (February 5, 1916): 154.

The National Archives in Atlanta has Logs of D. Love, Walter W. Osteen, Commodore G. “Germans Discharged from Coast Guard,” New

Lifesaving Stations, Entry 245. The only journals Huskey, Colon Hutchinson, and Guss Tyson, York Times, February 8, 1917, p. 2. Only natural-

available for this period were those for the Fort Station No. 203; Earl E. Kyzer, Station No. 204; H. ized Germans were allowed to remain in the U.S.

Lauderdale station: Fort Lauderdale, Florida, Spencer Fromberger, Ralph C. Bragg, George W. Coast Guard, U.S. Lighthouse Service, and the

Station Journal, May 19, 1917, to January 30, Duncan, and Buren W. Parsley, Station No. 205; U.S. Transport Service. All others were discharged.

1918. Also in Atlanta is Customs Inspector Francis Richards and Lawrence N. Borland, Station Felix J. Koch, “Keeping a City’s Police

Quinan’s report on “strange doings and night sig- No. 206; none at Station No. 207; Wallace King, Motorcycles in Repair,” The American City

nalings”: confidential letter titled “Motorcycle Alonzo Lee High, John Luther Simmons, Station (September 1917): 250. This article describes the

Patrol,” sent by J. W. Quinan (U.S. Navy Aid for No. 208; and Henry C. Matthans, Jerry Roberts, usefulness and problems of motorcycle patrols in

Information, Key West), August 20, 1917, to and Rudolph Roberts, Station No. 209. Wallace Cincinnati, Ohio. The primary use was to check

Inspector (Capt. D. P. Foley, USCG), Letters Sent King appeared a good choice. He was a partner in speeders exceeding eight miles an hour, but the

by the Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, and W. C. Leaird’s bicycle shop in Fort Lauderdale. motorcycles were under constant repair because

Thirteenth Districts, Eighth District, RG 26, Bertholf apportioned the stations and numbers of patrol work and rough roads.

NAB. The May 15, 1917, letter referenced by of motorcycles in a letter to the U.S. Navy Bureau “Coastal Telephone Service,” Proceeding of the

Quinan was not located. of Yards and Docks on June 19, 1917 (General U. S. Naval Institute 43 (March 1917): 584. On

Correspondence at the headquarters level is at Correspondence, 1935–1941, File Classification February 13, 1917, Navy Secretary Josephus

the National Archives Building (NAB) in 602, Station and Watch Bills, Seventh District, Daniels asked for a $250,000 congressional

Washington, D.C. The investigation of rumors of Entry 82B, RG 26): appropriation to enhance the Coast Guard “tele-

submarines being built on Hog Island is recorded in No. 202, Ormond, Fla. (2) phone signal service.” Daniels admitted the Coast

a report by 2nd Lt. William P. Wishaar, USCG: No. 203 Oakhill, Fla. (2) Guards telephone system was better than that of

“Investigation of Alleged Neutrality Violation,” No. 204 Titusville, Fla. (1) the War Department, Navy Department, and the

March 9, 1917, to his commanding officer, Capt. No. 205 Vero[Beach], Fla. (2) Lighthouse Service. He used the Coast Guard’s

Henry Ulke, General Correspondence, 8th District Superintendent, Jacksonville (2) communication model for his department.

1910–1935, File Classification 64, Cooperation No. 206 Fort Pierce, Fla. (1) However, there were no Coast Guard–connected

with Other Departments, State Neutrality, No. 208, Fort Lauderdale, Fla. (1) telephone systems south of Beaufort, N.C., and

Comanche, Entry 82A, RG 26, NAB. This report No. 209, Lemon City, Fla. (1) none on the Gulf Coast. However, the Coast

was classified “confidential” by the secretary of the No. 222, Point Isabel, Texas (1) Guard shrewdly allowed the Navy Department to

Navy on March 15, 1917, and declassified by Printed sources: “Saboteurs, Subversives take full control of its communication system

NARA (NND867200) on February 1, 1993. Thwarted,” The Coast Guard Reservist 10 (July with the full knowledge the system would return

Superintendent J. W. Richardson (Jacksonville, 1963): 1, 3. to the Coast Guard in an updated condition.

Florida) sent a May 26, 1917, telegram (General Evans, S. H. and A. A. Lawrence, “The History Digital sources: Google Patents (www.google.com/

Correspondence, 1935–1941, File Classification and Organization of the United States Coast patents, accessed February 10, 2009) for L. J.

602: Station and Watch Bills, Seventh District, Guard.” (U.S. Coast Guard Academy, 1938). This Husted’s patent No. 1,222,630 of April 17, 1917,

Entry 82B, RG 26) in response to a May 19, 1917, is the source of the 1938 Jacksonville District chart. “Ariel Torpedo Steering Mechanism.” A prolific

letter from Captain-Commandant E. P. Bertholf This history is unpublished, but some of it was used inventor, elements of Husted’s 1917 torpedo

(General Correspondence, 1910–1935, File later by Capt. Stephen H. Evans, USCG, in his patent was used in torpedo design into the 1970s.

Patrolling the Coastline on Wheels Prologue 45

Вам также может понравиться

- The Meaning and Making of EmancipationДокумент215 страницThe Meaning and Making of EmancipationPrologue Magazine100% (6)

- Marine Corps Aviation HistoryДокумент117 страницMarine Corps Aviation HistoryAviation/Space History Library100% (1)

- Naval Station NorfolkОт EverandNaval Station NorfolkРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Private Security Officer Basic TrainingДокумент284 страницыPrivate Security Officer Basic TrainingSrikanth KrishnamurthyОценок пока нет

- Baseball: The National Pastime in The National ArchivesДокумент137 страницBaseball: The National Pastime in The National ArchivesPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Sea Power Naval Aviation FinalДокумент48 страницSea Power Naval Aviation Finalsithusoemoe100% (3)

- Marines in The Frigate NavyДокумент35 страницMarines in The Frigate NavyBob AndrepontОценок пока нет

- The United States Marines The First Two Hundred Years 1775 1975Документ296 страницThe United States Marines The First Two Hundred Years 1775 1975Buck Lawhorn100% (1)

- Evolution of Aircraft Carriers: How Naval Aviation DevelopedДокумент74 страницыEvolution of Aircraft Carriers: How Naval Aviation Developedaldan63100% (2)

- ICS Reading ListДокумент10 страницICS Reading ListbookosmailОценок пока нет

- Lived Experiences of The Philippine Coast Guards Personnel in Performing Their FunctionsДокумент11 страницLived Experiences of The Philippine Coast Guards Personnel in Performing Their FunctionsMJBAS JournalОценок пока нет

- Will You Vote?Документ1 страницаWill You Vote?Prologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- The Ballast Water Treatment System Market 2012-2022Документ23 страницыThe Ballast Water Treatment System Market 2012-2022VisiongainGlobal100% (2)

- Maritime SecurityДокумент64 страницыMaritime SecuritySurendra Dasila100% (2)

- Small Unit Action In Vietnam Summer 1966 [Illustrated Edition]От EverandSmall Unit Action In Vietnam Summer 1966 [Illustrated Edition]Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (4)

- Ships Monthly 2019-04 PDFДокумент68 страницShips Monthly 2019-04 PDFAn CarОценок пока нет

- Infernal MachinesДокумент247 страницInfernal MachinesChris100% (1)

- The Ship that Held the Line: The USS Hornet and the First Year of the Pacific WarОт EverandThe Ship that Held the Line: The USS Hornet and the First Year of the Pacific WarОценок пока нет

- Managing The Rise of Southeast Asia's Coast GuardsДокумент12 страницManaging The Rise of Southeast Asia's Coast GuardsThe Wilson CenterОценок пока нет

- IndsarДокумент2 страницыIndsarSantosh DwivediОценок пока нет

- War of 1812: The IncredibleДокумент5 страницWar of 1812: The Incredibleapi-2331278530% (1)

- Somalia FishДокумент22 страницыSomalia FishOmar AwaleОценок пока нет

- Heroes in Dungarees: The Story of the American Merchant Marine in World War IIОт EverandHeroes in Dungarees: The Story of the American Merchant Marine in World War IIРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (6)

- USS Cyclops (AC-4)Документ7 страницUSS Cyclops (AC-4)Haron Al-kahtaniОценок пока нет

- Seabee HistoryДокумент168 страницSeabee Historypinoyjon100% (1)

- The Journals of Marine Second Lieutenant Henry Bulls Watson 1845-1848Документ434 страницыThe Journals of Marine Second Lieutenant Henry Bulls Watson 1845-1848Bob AndrepontОценок пока нет

- Battery E in France: 149th Field Artillery, Rainbow (42nd) DivisionОт EverandBattery E in France: 149th Field Artillery, Rainbow (42nd) DivisionОценок пока нет

- The Rhode Island Artillery at the First Battle of Bull RunОт EverandThe Rhode Island Artillery at the First Battle of Bull RunОценок пока нет

- Force Mulberry - The Planning and Installation of Artificial Harbor Off U.S. Normandy Beaches in World War IIОт EverandForce Mulberry - The Planning and Installation of Artificial Harbor Off U.S. Normandy Beaches in World War IIОценок пока нет

- Presidential yacht USS Mayflower (PY-1) served 5 US presidentsДокумент4 страницыPresidential yacht USS Mayflower (PY-1) served 5 US presidentsGustavoBilobranNevesОценок пока нет

- THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF COMMODORE CHARLES MORRIS, USN. (Some Excerpts)Документ12 страницTHE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF COMMODORE CHARLES MORRIS, USN. (Some Excerpts)Wm. Thomas ShermanОценок пока нет

- Summary of Phil Keith & Tom Clavin's To the Uttermost Ends of the EarthОт EverandSummary of Phil Keith & Tom Clavin's To the Uttermost Ends of the EarthОценок пока нет

- U-boat War off the U. S. Coast, 1942-45, Volume 2: Ebb Tide, Collapse, and Fall, May 1942 to May 1945От EverandU-boat War off the U. S. Coast, 1942-45, Volume 2: Ebb Tide, Collapse, and Fall, May 1942 to May 1945Оценок пока нет

- With the Battle Fleet Cruise of the Sixteen Battleships of the United States Atlantic Fleet from Hampton Roads to the Golden Gate, December, 1907-May, 1908От EverandWith the Battle Fleet Cruise of the Sixteen Battleships of the United States Atlantic Fleet from Hampton Roads to the Golden Gate, December, 1907-May, 1908Оценок пока нет

- The On The Roof GangДокумент3 страницыThe On The Roof GangTyler KirklandОценок пока нет

- Memoirs of Henry Villard Journalist and Financier 1835 -1900 Vol. IIОт EverandMemoirs of Henry Villard Journalist and Financier 1835 -1900 Vol. IIОценок пока нет

- "The Navy in The Civil War": Guidebook ToДокумент51 страница"The Navy in The Civil War": Guidebook TocomputertwoОценок пока нет

- Military History Anniversaries 1016 Thru 103116Документ12 страницMilitary History Anniversaries 1016 Thru 103116DonnieОценок пока нет

- Frank R Stockton - The Great War Syndicate: 'This proposition was an astounding one''От EverandFrank R Stockton - The Great War Syndicate: 'This proposition was an astounding one''Оценок пока нет

- The Battle of the Ironclads: The Monitor & The MerrimacОт EverandThe Battle of the Ironclads: The Monitor & The MerrimacОценок пока нет

- The Victory at Sea: American Destroyers in Action, Decoying Submarines to Destruction, The American Mine Barrage in the North Sea, German Submarines Visit the American Coast, The Navy Fighting on the LandОт EverandThe Victory at Sea: American Destroyers in Action, Decoying Submarines to Destruction, The American Mine Barrage in the North Sea, German Submarines Visit the American Coast, The Navy Fighting on the LandОценок пока нет

- Wwii Origins Newsela pt3Документ4 страницыWwii Origins Newsela pt3api-273260229Оценок пока нет

- 7obli 1943 C Chronicle-Lightbobs Crossing of The VolturnoДокумент20 страниц7obli 1943 C Chronicle-Lightbobs Crossing of The Volturnoapi-198872914Оценок пока нет

- The Battle of the Falkland Islands, Before and AfterОт EverandThe Battle of the Falkland Islands, Before and AfterОценок пока нет

- Bradstreet's Lightning Strike on Fort FrontenacДокумент12 страницBradstreet's Lightning Strike on Fort FrontenacjpОценок пока нет

- Postcard From The Lady Bird SpecialДокумент1 страницаPostcard From The Lady Bird SpecialPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Lady Bird and Lyndon B. Johnson in MinnesotaДокумент1 страницаLady Bird and Lyndon B. Johnson in MinnesotaPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Truman at Union StationДокумент1 страницаTruman at Union StationPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Jimmy Carter Campaign FlyerДокумент1 страницаJimmy Carter Campaign FlyerPrologue Magazine100% (1)

- The Woman Who VotesДокумент1 страницаThe Woman Who VotesPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Truman Campaign CarДокумент1 страницаTruman Campaign CarPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Ronald and Nancy Reagan in ColumbiaДокумент1 страницаRonald and Nancy Reagan in ColumbiaPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Nixon Greets StudentsДокумент1 страницаNixon Greets StudentsPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Housewives For TrumanДокумент1 страницаHousewives For TrumanPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Jimmy Carter, 1976Документ1 страницаJimmy Carter, 1976Prologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- George Bush CampaignsДокумент1 страницаGeorge Bush CampaignsPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- George W and Laura Bush CampaignДокумент1 страницаGeorge W and Laura Bush CampaignPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- George and Barbara Bush Aboard Air Force IIДокумент1 страницаGeorge and Barbara Bush Aboard Air Force IIPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Gerald Ford Campaign SwagДокумент1 страницаGerald Ford Campaign SwagPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- FDR Campaigns in Hyde ParkДокумент1 страницаFDR Campaigns in Hyde ParkPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Depression-Era Democratic Party Campaign PhotoДокумент1 страницаDepression-Era Democratic Party Campaign PhotoPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- FDR Campaigns in AtlantaДокумент1 страницаFDR Campaigns in AtlantaPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Betty and Gerald Ford at The RNCДокумент1 страницаBetty and Gerald Ford at The RNCPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower Whistle Stop TourДокумент1 страницаDwight and Mamie Eisenhower Whistle Stop TourPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Clinton Whistle Stop TourДокумент1 страницаClinton Whistle Stop TourPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- This Is AmericaДокумент1 страницаThis Is AmericaPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Clinton at A Get Out The Vote Rally in Los AngelesДокумент1 страницаClinton at A Get Out The Vote Rally in Los AngelesPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- Anti-FDR Campaign ButtonsДокумент1 страницаAnti-FDR Campaign ButtonsPrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

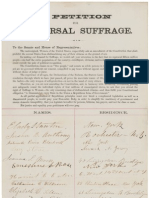

- Petition For Universal SuffrageДокумент1 страницаPetition For Universal SuffragePrologue MagazineОценок пока нет

- MaritimeProfessional 2011 11Документ68 страницMaritimeProfessional 2011 11karen13Оценок пока нет

- Maritime Security Act 2002Документ72 страницыMaritime Security Act 2002cademarestОценок пока нет

- QF4 Autumn 2018 WebДокумент44 страницыQF4 Autumn 2018 WebQF4Оценок пока нет

- Manipon Chapter 4,5 NewДокумент7 страницManipon Chapter 4,5 Newelizabeth monasterioОценок пока нет

- G Integrated Offshore Emergency Response TMДокумент92 страницыG Integrated Offshore Emergency Response TMromedic36Оценок пока нет

- Thayer, A Malaysian Strategy of Pre-Emption - China and South China SeaДокумент16 страницThayer, A Malaysian Strategy of Pre-Emption - China and South China SeaCarlyle Alan ThayerОценок пока нет

- Mumbai Oil Spill and Its Effect On EnvironmentДокумент6 страницMumbai Oil Spill and Its Effect On EnvironmentRamcharan RajОценок пока нет

- The Mariner Maritme LawДокумент113 страницThe Mariner Maritme LawBi OfficialОценок пока нет

- DifferencesДокумент5 страницDifferencesRobert oumaОценок пока нет

- MGN 471 (M) : Maritime Labour Convention, 2006: DefinitionsДокумент10 страницMGN 471 (M) : Maritime Labour Convention, 2006: DefinitionsVadim RayevskyОценок пока нет

- GMCP Annual Report 2018 PDFДокумент60 страницGMCP Annual Report 2018 PDFAnonymous L3QBeRОценок пока нет

- Sample Position PaperДокумент19 страницSample Position PaperWayne C.Оценок пока нет

- Oct - Part 1&2 - BN-BE ChapterДокумент9 страницOct - Part 1&2 - BN-BE Chapterdhydro officeОценок пока нет

- Thayer Implications of A Chinese Military Presence at Cambodia's Ream Naval BaseДокумент2 страницыThayer Implications of A Chinese Military Presence at Cambodia's Ream Naval BaseCarlyle Alan ThayerОценок пока нет

- 3 - T-3 Customs JurДокумент3 страницы3 - T-3 Customs JurKesTerJeeeОценок пока нет

- Overview of Coast Guard Drug and Migrant Interdiction: HearingДокумент90 страницOverview of Coast Guard Drug and Migrant Interdiction: HearingScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- 5.6 - Strait of Bonifacio - Maritime Safety ReinforcementДокумент15 страниц5.6 - Strait of Bonifacio - Maritime Safety ReinforcementEliza PopaОценок пока нет

- Rule: Ports and Waterways Safety Regulated Navigation Areas, Safety Zones, Security Zones, Etc.: Broad Sound, Revere, MAДокумент3 страницыRule: Ports and Waterways Safety Regulated Navigation Areas, Safety Zones, Security Zones, Etc.: Broad Sound, Revere, MAJustia.comОценок пока нет

- Coast Guard Civil Rights Manual Cim - 5350 - 4CДокумент166 страницCoast Guard Civil Rights Manual Cim - 5350 - 4CcgreportОценок пока нет

- Pub. 140 North Atlantic Ocean and Adjacent Seas (Planning Guide), 12th Ed 2013Документ674 страницыPub. 140 North Atlantic Ocean and Adjacent Seas (Planning Guide), 12th Ed 2013cavrisОценок пока нет

- 06 June 1998Документ100 страниц06 June 1998Monitoring TimesОценок пока нет

![Small Unit Action In Vietnam Summer 1966 [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/299705772/149x198/0346f009af/1617221092?v=1)