Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Reducing Levels of Compassion Fatigue For Nurses in An Acute Care Inpatient Hospice Unit

Загружено:

api-247952145Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Reducing Levels of Compassion Fatigue For Nurses in An Acute Care Inpatient Hospice Unit

Загружено:

api-247952145Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE 1

Reducing Levels of Compassion Fatigue for Nurses in an Acute Care Inpatient Hospice Unit Brooke Delaney University of California, Los Angeles

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE 2

PHASE I: VALIDATION PHASE Clinical Problem Nurses who care for patients with cancer often interact with the dying or those nearing death. Oncology nurses frequently struggle with emotional distress due to loss after having intense, caring relationships with patients and their families. Administering care to patients with cancer can increase the risk of psychological disorder, stress and compassion fatigue, particularly for those providing palliative care to cancer patients (Sabo, 2008). Compassion fatigue, a traumatizing emotional state experienced by caregivers preoccupied by the suffering of those they are caring for (Figley, 2002), has been classified as a type of collateral stress and may result in an overall immune system decline, headaches, anger, weariness, apathy, disrupted sleep, depression, a tendency to be more accident prone, and a desire to quit. Facilities that provide for cancer patients may face complex challenges when dealing with high acuity and increased volume in tandem with poor staff retention. Beth Israel Medical Center, situated along Manhattans East Side Hospital Row or Bedpan Alley is one of the more poorly funded hospitals in the affluent vicinity and, primarily services a lower-income community with a high-volume demand for services. Its hospice unit is an inpatient, 26-bed floor, which provides acute care for end-of-life patients, the majority of whom are cancer patients, whose symptoms cannot be managed at home or in a nursing home. The unit also provides temporary respite care for families experiencing extreme caregiver burden. Patient stay on the unit averages 15 days and nurse to patient ratio averages 1:5. In the past 2 years, staff retention has declined significantly, patient demand has risen, and overall staff morale seems low as evidenced by self-report, an increase in absence due to illness and frequent interpersonal conflict amongst the nursing staff that must be mediated by the nurse manager.

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE 3

This pilot study will implement a set of wellness program interventions, outlined by Zadeh and colleagues (2012), into the hospice unit and is aimed towards promoting self-care, education, and team-building with the overarching goal of decreasing practitioner compassion fatigue, practitioner stress and staff infighting. Long-term objectives include an increased level of nursing staff retention and higher rate of reported compassion satisfaction from the nursing staff. Article #1 Aycock, N., & Boyle, D. (2009). Interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nursing. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 13(2), 183-191. Article #2 Potter, P., Deshields, T, Divanbeigi, J. Berger, J.D., Cipriano, D. Norris, L, & Olsen, S. (2010) Compassion fatigue and burnout: Prevalence among oncology nurses. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 14(5). E56-E62. Article #3 Zadeh, S., Gamba, N., Hudson, C., & Wiener, L. (2012). Taking care of care providers A wellness program for pediatric nurses. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 29(5), 294-299. Literature Review Aycock, N., & Boyle, D. (2009). Interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nursing. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 13(2), 183-191. Aycock and Boyles (2009) study set out to identify available workplace resources to alleviate compassion fatigue such as work environment, work support and educational interventions. A questionnaire was devised in consultation with a pilot group representative of diverse roles in the oncology field, and subsequently the short survey was emailed with an accompanying explanatory letter to 231 chapter presidents of the Oncology Nursing Society

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE 4

(ONS). This cross-sectional, correlational study utilized a standardized survey tool aimed at assessing accessibility to on-site professional resources, provision of education programs and retreat availability. The investigators extrapolate from numerous earlier studies on the phenomenon of burnout, notably the clinically recognized findings of Radziewicz (2001), which elucidated the effects of maladaptive coping techniques, which can lead to symptoms of illness, exhaustion, and any physical and psychological distress. They deduce that interventions to manage stressors and improve coping skills must be identified for those working in oncology. The investigators found that the availability of interventions, including on-site professional resources (i.e. Employee Assistance Programs - EAP, pastoral care, counselors), education addressing work-place coping (i.e. End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium classes - ELNEC) and off-site retreats, ranged from 0%-60%. No participants reported mandatory participation in ELNEC classes, while a 62% majority reported having access to an EAP. It was concluded that organizations and management systems must increase levels of awareness in regards to under recognized hazards of CF in staff populations and be encouraged to inventory support offerings and enhance workplace interventions. Though the sample size of 103 participants was adequate to determine findings, the response rate of 27% was one apparent limitation. It is noted that future surveys should also address quantification of the frequency of use of interventions and if this was at all correlated with role or retention. Potter, P., Deshields, T, Divanbeigi, J. Berger, J.D., Cipriano, D. Norris, L, & Olsen, S. (2010) Compassion fatigue and burnout: Prevalence among oncology nurses. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 14(5). E56-E62.

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE 5

Potter (2010) implemented a quality improvement study in order to evaluate the degree to which healthcare workers at a large National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center were experiencing compassion fatigue. The investigators administered a 30-item Professional Quality of Life scale: ProQOLR-IV (Stamm, 2009) to 153 healthcare providers. Included were nurses, medical assistants and radiology technicians working in oncology units. Developed by Stamm, the ProQOL is a tool which measures the pleasure one derives from being able to do work well, feelings of hopelessness and difficulties in dealing with work or in doing ones job effectively, and work-related, secondary exposure to extremely stressful events. Potter et al (2010) compared their results to those of Stamm (2009), which had been collected from a sample of 436 people. Potter et al (2010) found that the oncology staff had higher levels of compassion satisfaction, reflective of a sense of fulfillment elicited from doing work well. Even so, results also demonstrated higher than average scores for compassion fatigue or secondary traumatic stress. Additionally, findings indicate that compassion satisfaction scores were lower for inpatient healthcare staff when compared with those working in outpatient units. Though the factors contributing to workplace stress are many and multifaceted (e.g. the nature of cancer, intense involvement with patients and families role ambiguity, workload, surrogate decision making, palliative care issues) it was concluded that work in oncology practice definitely warrants skill enhancement for optimal coping. Of particular interest, individuals who had worked 11-20 years in oncology had the greatest number of high-risk scores for all three ProQOL R-IV subscales and there was a greater amount of burnout and compassion fatigue among nurses with higher levels of education. The investigators planned to implement findings

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE 6

indicative of the need for interventions for at-risk staff with the development of a program model for self-care training for staff and staff retreats. A limitation to this study was the small sample size and a small amount of data collected from medical assistants and radiologists. Also of note, the there is potential for response bias in the results, as staff who chose not to respond might have had lower levels of compassion fatigue and burnout. Zadeh, S., Gamba, N., Hudson, C., & Wiener, L. (2012). Taking care of care providers: A wellness program for pediatric nurses. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 29(5), 294-299. Zadeh and colleagues sought to determine if interventions aimed at promoting wellness and reducing stress could be implemented and thereby effect job satisfaction in a small population of pediatric oncology nurses. The investigators study outlines a newly developed 10-session, 1-hour, team-based, wellness program that was offered twice to a sample of staff providing pediatric oncology care in a 22-bed pediatric inpatient unit and an outpatient pediatric clinic at the NIH clinical Center in Bethesda, MD. This was a quantitative, descriptive study, which evaluated formal evaluations that were collected from the program participants at the end of each session. A total of 126 staff evaluations were completed and evaluated. 75% or more of the responses were positive in regards to the wellness programs effect on morals, ability to enhance job performance and delivery of self-care models. Some respondents reported that they enjoyed learning new methods of self-care and the program helped them feel more at peace with the passing away of a patient in their care.

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE 7

Limitations to the study include the small population studied and the lack of administration involvement in the program. Further studies could explore implementing such programs for the entirely of the staff and tracing the effects of tools learned over a longer period of time. Synthesize The notable prevalence of compassion fatigue reported among oncology nurses is indicative of a need for healthcare organizations to better assess the vulnerability of their staff and implement appropriate interventional programs. Aycock (2009) illuminates the dearth of interventions to counter the emotional ramifications of nursing care to oncology patients while Potter (2010) reemphasizes the cruciality of offering skill training and self-care programs to nurses to ensure the overall constitution of an organization and to ensure the best outcomes for both patients and staff. Prioritizing the emotional and psychological well being of employees must be an imperative for administrators of any type of oncology unit. Taking measures to identify changeable unit practices, promote team building and encourage the individual well being of the nurse are all tactics that should be implemented at Beth Israels hospice unit. PHASE II: COMPARATIVE EVALUATION PHASE Fit of Setting The findings from each of the three articles reviewed are exceedingly appropriate for my clinical setting. Each paper focuses on with one specific population of oncology nurses struggling with burnout or the effects of compassion fatigue on larger groupings of separate oncology units with high rates of death among the patient populations. Substantiating Evaluation Despite using different tools and different foci of measurement, the results of all three studies were indicative of a lack of self-care resources for oncology nurses and the great need to

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE 8

combat compassion fatigue and burnout. It is evident from Zadehs small study that such interventions improve outcomes and numerous reports from Aycocks survey show that health care staff feel the lack appropriate resources to combat distress and that a sea change is critical. Basis for Practice My intervention would be implementation of a year-long, monthly-occurring, groupbased wellness program inclusive of all levels of the nursing staff as well as medical assistants and technicians which would be formulated after getting confidential input from each unit staff member. Each session would address offer a variety of skill sets to enhance self-care and encourage better communications between staff members. The evidence-based model incorporated is the ACE Star Model of Knowledge Transformation. The knowledge discovery phase would be a time during which the outside, impartial wellness program facilitators met individually with each participant to gather input regarding their challenges and unmet needs in regards to coping with burnout and unit support. Additionally, suggestion boxes would be placed on the unit for anonymous topic suggestions. The wellness team would gather input into an evidence summary, which would inform the most pressing needs to be addressed during the wellness programs. Recommendations for translation into practice could be infused into the skills offered during the programs themselves, which will be conducted to accommodate both daytime and nighttime staff. Integration into practice could involve bringing discussion of the wellness skill sets and their efficacy into staff weekly meetings and evaluation would be undertaken at the end of each month to assess progress as well as at the end of the first year of the program to review staff morale, retention and additional response. Feasibility

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE 9

Foreseeable benefits of offering an interventional wellness program on the unit would be overall improvement in staff morale, sense of job satisfaction, better staff relations, better staff retention and improved experiences for patients and families. Disadvantages might include reluctance to participate due to time constraints or other factors, as well as the possibility that staff might not want to make themselves vulnerable within the context of the wellness program if higher-level staff is participating simultaneously. PHASE III: DECISION-MAKING PHASE Pilot Study As stated, a monthly wellness program with the aforementioned guidelines (Basis for Practice) would take place on the unit over the course of one year. Descriptive, minimum data set (MDS), anonymous questionnaires would be available to staff as well as confidential interviews with wellness counselors. The MDS surveys will use a 7-point Likert scale to assess factors including moral distress, job satisfaction and ability to cope. Once a 70% response is received from the units staff, results will be used to set priorities for each of the 12-wellness program sessions. All staff that have interaction with the patient population will participate in the group programs, and must be amenable to the implementation of this change. Sessions will take place is an environmentally calming setting, ideally a private meeting space in a separate part of the hospital or one of the hospital gardens. Sessions will include verbal education, hands-on activity, interactive activity and reading and writing reflections. Group discussion would culminate each session as well as formal evaluations by each staff member to assess major take-aways. Ideally staff will be motivated to participate because the programming will enable them to find ways to decrease their levels of compassion fatigue. Administrators should find similar motivation, as well as the prospect of contributing to improved staff morale, which would

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE 10

facilitate better unit management. Some barriers to change might be individual need for privacy, a hesitancy to grieve or show emotion, cultural concepts that shun such interpersonal encounters in a work setting or an unwillingness to open up emotionally in a group setting. In an effort to overcome these barriers, I would initially offer results from similar interventions attesting to its benefits, perhaps by bringing in former participants in other wellness programs. Additionally, I would offer some sort of small financial incentive for participatory staff, such as a complementary lunch or dinner. Following the year of wellness program implementation, the organizers would compile the evaluations and do another round of private interviews with participatory staff. This data would be assembled into a power point presentation as well as a small newsletter to be distributed to hospital administration. This information can be disseminated both on the immediate unit at weekly staff meetings, as well as to upper level administration at Beth Israel at monthly meetings. The newsletter with reported findings will also be distributed to ancillary staff in their personal mailboxes. This includes, but is not limited to, attending physicians, technicians, and medical assistants. A poster will be created with positive personal accounts relating to the wellness program that can be hung in the hallway for patients and the public to see. Lastly, we would work with Beth Israels public relations team to include an article about the hospice units new wellness program in the hospitals monthly newsletter, which is available to the general public. The article would be clear, easy for the layman to understand, and include benefits found though the wellness program that would be advantageous for any member of the public, not just oncology nurses.

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE 11

Three months after the culmination of the wellness program intervention, we would follow-up with the unit to determine if there were any changes in staff relations, staff moral and staff retention. If it were found to be beneficial, we would aim to implement more programs to this and other high-risk units.

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE 12

References Aycock, N., & Boyle, D. (2009). Interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nursing. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 13(2), 183-191.doi:10.1188/09.c.jon.183191 Figley, C. R. (2002). Treating compassion fatigue (No. 24). Routledge. Potter, P., Deshields, T, Divanbeigi, J. Berger, J.D., Cipriano, D. Norris, L, & Olsen, S. (2010) Compassion fatigue and burnout: Prevalence among oncology nurses. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 14(5). E56-E62. doi: 10.1188/10.c.jon.e56-e62 Radziewicz, R. M. (2001). Self-care for the caregiver. The Nursing clinics of North America, 36(4), 855. Sabo, B. M. (2008). Adverse psychosocial consequences: Compassion fatigue, burnout and vicarious traumatization: Are nurses who provide palliative and hematological cancer care vulnerable?. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 14(1), 23 Stamm, B. H. (2009). Professional quality of life: Compassion satisfaction and fatigue version 5 (ProQOL). 2o1 1032o3. http://www. isu. edu/bhstamm. Zadeh, S., Gamba, N., Hudson, C., & Wiener, L. (2012). Taking Care of Care Providers A Wellness Program for Pediatric Nurses. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 29(5), 294-299. doi: 10.1177/1043454212451793

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE

13

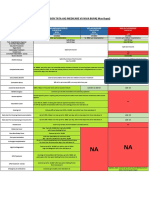

CITATION Aycock, N., Boyle, D. (2009). Interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nursing. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing 13(2), 183191. doi:10.1188/09.c.jon.183191

PURPOSE Cross-sectional study conducted via national survey to identify resources available to oncology nurses to mitigate compassion fatigue.

SAMPLE/SETTING N=103. Questionnaire was sent to 231 Oncology Nursing Society chapter presidents with 103 respondents (44%).

METHODS Questionnaire for oncology nurses was developed by a pilot group to address three major categories: accessibility to on-site professional resources, provision of educational programs and retreat availability. Questionnaire took less than 5 minutes to complete, allowed participants to check area resources, provide comments and asked for minimal, optional demographic information.

RESULTS Sixty-two of the ONS chapters receiving the survey provided it least one response with a total of 103 responses. Responses received aggregated in a table form and narrative comments were grouped according to theme. Availability of interventions ranged from 0%-60%. No participants reported mandatory participation requirement in the End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) courses, and 62 (60%) reported availability of an employee assistance program (EAP).

DISCUSSION & LIMITATIONS Interventions to combat compassion fatigue are available to a relatively small subset of oncology nurses, results of this survey indicate blueprints for practioners to replicate in practice settings. Interventions explored include guidance in coping (breaks, meditation, work/life balance), managements acknowledgement of risk, training in formal competencies, space for emotional expression, pastoral care, retreats, peer support and program planning. Limitations included: the 27% response rate made generalization of findings difficult; some ONS chapters did not assemble when the study was being conducted. Future studies should seek outcome data and quantify use of strategies.

RUNNING HEAD: COMPASSION FATIGUE

14

Potter, P., DeShields, T., Divanbeigi, J., Berger, J., Cipriano, D., Norris, L., Olsen, S. (2010). Compassion fatigue and burnout: Prevalence among oncology nurses. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 14 (5), E56-E62. doi: 10.1188/10.c.jon.e56-e62

Cross-sectional survey and descriptive analysis of a qualityimprovement evaluation was conducted in inpatient nursing units and outpatient clinics in a large, National Cancer Institute-designated cancer center in the Midwestern United States.

Total of 448 survey packets distributed to staff including nurses, medical assistants and technicians in five inpatient oncology units, four outpatient chemotherapy infusion areas, and three physician office practice areas. Most respondents were RNs.

Zadeh, S., Gamba, N., Hudson, C., Wiener, L. (2012). Taking care of care providers: A wellness program for pediatric nurses. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 29 (5), 294299. doi: 10.1177/1043454212451793

10-session wellness program, which was offered on 2 occasions as an intervention for the cumulative effect of stress and compassion fatigue for a selection of oncology nurses.

Program was implemented and subsequently evaluated (126 evaluations completed) at an NIH Clinical Center providing pediatric care in a 22-bed inpatient unit, and outpatient day hospital and outpatient clinic

Evaluation involved the distribution of the 4th revision of the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL R-IV) scale to all eligible staff. Completition of the 30-item tool involves selecting response choices on a 0(never)-5(very often) Likert scale. Compassion satisfaction, burnout and trauma or compassion fatigue were constructs measured. Sessions were developed based on nurses requests and topics of interest were incorporated

Total of 153 healthcare providers participated with a response rate of 34%. Avg. compassion score among all participants was 38.3 (SD=7.2), avg. burnout score 21.5 (SD=6.4), avg. compassion fatigue 15.2 (SD=6.6). Groups found to be at highest risk included those working on inpatient units and staff with 11-20 years of oncology experience.

Results limited by small sample size and small number of responses from medical assistants and radiology technicians. Additional limitation is potential response bias. Cross-sectional design does not allow for understanding of changes over time, collected data was limited by constraints of the qualityimprovement project and differences between inpatient and outpatient practice should be further explored.

Вам также может понравиться

- Ucla Son Clinical Skills ChecklistДокумент31 страницаUcla Son Clinical Skills Checklistapi-247952145Оценок пока нет

- Clinical Nurse Leader Portfolio 1Документ7 страницClinical Nurse Leader Portfolio 1api-247952145Оценок пока нет

- Policy Issue - End of Life CareДокумент6 страницPolicy Issue - End of Life Careapi-247952145Оценок пока нет

- Chla-Portfolio ResumeДокумент2 страницыChla-Portfolio Resumeapi-247952145Оценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Access, Assessment & Continuity of CareДокумент14 страницAccess, Assessment & Continuity of CareamitОценок пока нет

- MediSafe Infinite PDFДокумент21 страницаMediSafe Infinite PDFNazim SalehОценок пока нет

- Curriculum Vitae Education UsmДокумент3 страницыCurriculum Vitae Education Usmapi-360825472Оценок пока нет

- Vice President or Executive Director or DirectorДокумент4 страницыVice President or Executive Director or Directorapi-77396522Оценок пока нет

- F. FeasibilityДокумент2 страницыF. Feasibilitypatricia gunioОценок пока нет

- To Identify Irrational Beliefs, Locus of Control, Quality of Work Life Among Nurses Working in Government and Corporate HospitalsДокумент8 страницTo Identify Irrational Beliefs, Locus of Control, Quality of Work Life Among Nurses Working in Government and Corporate HospitalsAnonymous CwJeBCAXpОценок пока нет

- A Patient's Bill of RightsДокумент4 страницыA Patient's Bill of RightsMark ElbenОценок пока нет

- Dr. Farzana Rashid Hossain - 2016 Women of DistinctionsДокумент64 страницыDr. Farzana Rashid Hossain - 2016 Women of DistinctionsFarzana Rashid Hossain, MDОценок пока нет

- Cover Letter ExampleДокумент2 страницыCover Letter ExampleChristina VongОценок пока нет

- Final Reflective StatementДокумент4 страницыFinal Reflective StatementPham KarinaОценок пока нет

- Health InsuranceДокумент9 страницHealth InsurancetceterexОценок пока нет

- Hospital Management SolutionДокумент4 страницыHospital Management SolutionsomyaОценок пока нет

- Obm752 Hospital Management QBДокумент43 страницыObm752 Hospital Management QBParanthaman GОценок пока нет

- Improving Hospital Performance and Productivity With The Balanced Scorecard - 2Документ22 страницыImproving Hospital Performance and Productivity With The Balanced Scorecard - 2Yunita Soraya HusinОценок пока нет

- Ppg-Gdch-Nur-42 Policy On Patient IdentificationДокумент7 страницPpg-Gdch-Nur-42 Policy On Patient IdentificationKenny JosefОценок пока нет

- SOP FinalДокумент7 страницSOP FinalsabaОценок пока нет

- Cover Letter ChlaДокумент1 страницаCover Letter Chlaapi-405154325Оценок пока нет

- Test 14Документ5 страницTest 14MH GamingОценок пока нет

- مشروع ادارة مستشفىДокумент130 страницمشروع ادارة مستشفىboothoОценок пока нет

- Role of Pharmacist in Reducing Healthcare CostsДокумент8 страницRole of Pharmacist in Reducing Healthcare CostsAnsar MushtaqОценок пока нет

- Hailey Carr Hughes ResumeДокумент2 страницыHailey Carr Hughes Resumeapi-533884212Оценок пока нет

- ResourcesДокумент104 страницыResourcesAbdoul Hakim BeyОценок пока нет

- Medical Services and ManagementДокумент17 страницMedical Services and ManagementjohnОценок пока нет

- Comparison Tata Aig Medicare Vs Niva BupaДокумент1 страницаComparison Tata Aig Medicare Vs Niva BupaTikekar ShubhamОценок пока нет

- Nawab Bugti AgreementДокумент6 страницNawab Bugti AgreementYounas BugtiОценок пока нет

- Annex A - Self-Assessment Tool For Proposed EPCB Health Facilities PDFДокумент5 страницAnnex A - Self-Assessment Tool For Proposed EPCB Health Facilities PDFCora Mendoza100% (1)

- PDFДокумент245 страницPDFSunil SewakОценок пока нет

- Enhanced E-R Model and Business RulesДокумент20 страницEnhanced E-R Model and Business RulesAbdirisak Mohamud0% (1)

- Vignette 1. Concepts of L&MДокумент4 страницыVignette 1. Concepts of L&MJohn Lyndon SayongОценок пока нет

- Philippine Health CareДокумент8 страницPhilippine Health CareCarl Mark Vincent BabasoroОценок пока нет