Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Calkins Summary

Загружено:

api-2620073700 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

38 просмотров16 страницОригинальное название

calkins summary

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

38 просмотров16 страницCalkins Summary

Загружено:

api-262007370Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 16

www.TheMainIdea.net The Main Idea 2012. All rights reserved.

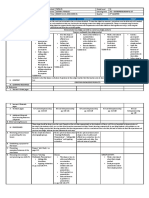

S.O.S. (A Summary of the Summary )

The main ideas of the book are:

~ This book provides a clear and thoughtful discussion of the Common Core State Standards in literacy

that leads to a better understanding of them.

~ Because the standards only map out expectations, not instructional approaches, the book helps to fill in

the gaps by providing suggestions for implementation.

Why I chose this book:

There is no doubt; getting students to achieve the standards outlined in the Common Core State Standards is daunting.

These are challenging standards. However, understanding the standards themselves doesnt also need to be a challenge.

Thats why I chose this book. Calkins and colleagues have created a useful resource that thoughtfully walks us through

the literacy standards standard by standard unpacking the document and making it accessible along the way.

For me it was like a travel guide. It showed me how to read the standards, how the standards are organized, and what

the standards might look like in a classroom. What was most useful was that it highlighted what was important about

the standards. In the end, it made the standards a lot less scary for me.

This book is for any school leader, literacy coach, or teacher who is involved with launching a Common Core literacy

initiative and wants to make sure to be informed. In the book each chapter follows the same format. First a few

standards are discussed and explained so you can develop a richer understanding of them. Then the authors offer a few

implementation suggestions or pathways to give teachers ideas for ways to help students meet those standards.

The Scoop (In this summary you will learn)

! While some educators are skeptical about the Common Core, you will learn to use what is golden about these standards to

support necessary and dramatic improvements in your school.

! While the standards may seem overwhelming, you will learn that because of the way they are organized, you really only

need to learn ten anchor standards and then understand how these are rolled out in grades K-12.

! While some fear that these standards are far too rigorous to be achieved, you will learn, by reading the standards

horizontally from grade to grade, that the incremental changes from year to year are manageable

! In order to increase your students reading levels you need to know their reading levels. Without having a leveling system

in place such as the Fountas and Pinnell system you will learn ways to assess text complexity yourself.

! Professional development activities to help teachers better understand and use the CCSS are at the end of the summary.

PATHWAYS TO THE COMMON CORE: Accelerating Achievement

By Lucy Calkins, Mary Ehrenworth, & Christopher Lehman (Heinemann, 2012)

F

i

l

e

:

C

o

m

m

o

n

C

o

r

e

S

t

a

t

e

S

t

a

n

d

a

r

d

s

-

-

L

i

t

e

r

a

c

y

1 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

Chapter 1 -- An Introduction to the Common Core State Standards

The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) are a big deal. Not only have 45 states adopted them so far, but this is the most dramatic

reform of K-12 education our country has ever seen. These standards will affect what is taught, what is tested, what is published, and

what is mandated in schools. It is vital that every educator has a deep understanding of these standards because although the standards

map out expectations, it is up to educators to determine how to achieve these ambitious goals. It is important to reiterate the CCSS

just outline what the students are expected to know and be able to do, teachers must interpret what they imply for the classroom.

While educators may have some complaints and concerns about these new standards, this book will help you see what is golden in

the standards and how you can implement the CCSS in ways that improve student-centered and interactive approaches to literacy. If

we understand what is good about the CCSS, we can use these them to support necessary and dramatic improvements in our schools.

What is golden about the Common Core State Standards?

The CCSS provide an urgently needed wake-up call: The world has changed. Twenty-five years ago 95% of our jobs required

lower-level skills. Today, only 10% of our economy consists of low-skills jobs. New levels of literacy are essential in todays world

and yet students leave schools without strong literacy skills.

The CCSS emphasize a much higher level of comprehension skills: The CCSS are replacing NCLB which held phonics on equal

par with comprehension. With one glance at the CCSS you can see that this document places a much stronger emphasis on higher-

level comprehension. For example, even younger students are expected to find similarities and differences in points of view and to

analyze various accounts of an event. This is a far cry from the previous focus on basal reading programs and seatwork under NCLB.

The CCSS increase the emphasis on writing: With NCLB there was NO mention of writing. Now the CCSS place equal

importance on both reading and writing.

The CCSS are clear and succinct: In many states, educators are used to an overwhelming number of standards. In contrast, you

have to admire the clean, coherent design of the CCSS. The document itself says that standards should be: high, clear, and few, and

the CCSS meet these criteria. There are 10 anchor standards in reading and 10 in writing and these are rolled out in grades K-12.

The CCSS acknowledge that growth occurs over time: The CCSS send a clear message growth takes time. Teaching a skill is

never solely the responsibility of the fourth grade teacher or the tenth-grade teacher. For example, with reading anchor 2 (determining

central ideas of texts and analyzing their development) there is a progression of skills needed to meet this standard in each grade. For

first graders this means being able to retell a story with details and for eighth graders being able to analyze how themes develop and

interact. This type of progression requires that schools have a spiraled curriculum in which students develop skills over time. The

authors of the CCSS took the skills students need for college and carefully planned backwards for the skills they would need at each

grade level, all the way down to kindergarten, in order to be prepared for college-level skills by graduation.

The CCSS respect the professional judgment of teachers: The CCSS state: The Standards define what all students are expected

to know and be able to do, not how teachers should teach. Teachers must rely on their skills and knowledge to bring students to the

ambitious levels outlined in the CCSS.

Implementing the Common Core

The most challenging aspect of the CCSS is yet to be figured out: how best to implement them. The goals of the document are clear,

but the pathway is not. While it is vital to know the standards themselves inside out, it is even more essential to know what resources

you already possess and the challenges you face as you implement them. Below are some general implementation suggestions to start.

First look at your current literacy initiatives and set goals for how to improve them.

Even if you believe your current literacy approaches are already aligned to the Common Core, take a more in-depth and honest look at

classroom practice (perhaps with a schoolwide walk-through) to determine how your school might improve student work and teaching

to meet CCSS. Take a particularly close look at whether the school has strong systems and habits of continuous literacy improvement.

Next, find ways to better align your curriculum to the CCSS.

Develop a K-12, spiraled, cross-curricular, writing curriculum. Writing is a fairly inexpensive place to start because you dont need to

purchase a lot of expensive materials and there is a lot of agreement that the writing process approach is the best way to proceed.

Implement a spiral writing curriculum that has all students working on information, argument, and narrative writing at the CCSS level,

and provide students with an hour a day to write in order to help them meet these standards. Furthermore, this emphasis on writing

should occur across the curriculum in all subject areas.

Provide students with just-right high-interest texts and time to read them. In order to improve students understanding of complex

texts, as is required in the CCSS, schools need to provide students with lots of interesting texts and at least 45 minutes of reading time

in school (plus more at home). In order to do this, schools must know the level at which their students are reading.

2 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

Schools strong in the above areas should focus on higher levels of reading and writing. If your students are moving up in their levels

of text difficulty make sure they are using increasingly higher-order comprehension skills. Some students may be using the same level

of comprehension in second grade as they use in the sixth grade. For example, in second grade they may write, Poppleton is a good

friend because but this may be no different from their thinking when they reach sixth grade, Abraham Lincoln is humble

because Another area most schools have room for improvement is in not only increasing the number of nonfiction texts students

read, but also going beyond reading for comprehension to reading with a much more analytical approach. The Common Core asks

students to read several texts about a single topic, determine the central ideas, issues, and disputes, and anticipate arguments. This

means students need to do more than read a summary of the American Revolution they now need to read a wider range of texts such

as speeches, propaganda, and other documents with varying points of view. If students write solidly in your school, then boost their

writing levels in argument and informational writing since the levels required for these types of writing in the CCSS is high!

Chapter 2 OVERVIEW of the READING STANDARDS

Key Aspects of the Common Core State Standards in Reading

Whatever concerns people may have about the CCSS in reading, there are two undisputed aspects of these standards that make them

incredibly user-friendly that are described below.

(1) The beauty and efficiency of their organization The standards are beautifully organized. The reading standards are comprised of

ten anchor standards. There are sets of ten standards for reading, both fiction and also for reading informational texts, and each of

these sets of standards address the same skill set. Furthermore, these ten anchor standards are the same for every grade its just that the

complexity of the skill increases as the grades go up. For example, the chart below shows how the skill of determining the main idea

(standard 2 in reading informational texts) gets more complex as students progress from third to fifth grade:

Standard Number Grade 3 students: Grade 4 students: Grade 5 students:

2 Determine the main idea of a text; recount

the key details and explain how they

support the main idea.

Determine the main idea of a text

and explain how it is supported by

key details; summarize the text.

Determine two or more main ideas of a

text and explain how they are supported

by key details; summarize the text.

Because there are only ten anchor standards, the CCSS send a clear message about what should be prioritized in reading. Unlike other

standards, this document does not intend to be all things to all people. Rather than wade through dozens and dozens of standards to

determine which ones should be emphasized, teachers can now look to this new document and understand the ten enduring reading

skills that are important for students of any age.

(2) The emphasis on deep comprehension and high-level thinking Unlike the lower-level skills such as sound-letter correspondence

that were emphasized under NCLB, the new CCSS require the development of high-level skills for even the youngest learners. For

example, even kindergarteners are expected to ask and answer questions about key details in the text (standard 1). While sound-

letter correspondence and other such skills are in the CCSS, they are in their own section, not in the reading or writing standards.

Therefore reading, according to the Common Core, is all about making meaning.

What the CCSS Do and Dont Value in Reading

Which high-level reading comprehension skills are covered in the CCSS? The phrases that are repeated throughout the K-12 reading

standards include: close, attentive reading, reasoning and use of evidence, comprehend and evaluate, evaluate other points of

view critically, cite specific evidence, demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly to the text, compare and

contrast, etc. However, it is also important to note what is not in the standards: make text-to-self connections, access prior

knowledge, and relate to your life. Overall, the CCSS move away from the idea of reading as a personal act and move more toward

reading as textual analysis. This type of highly academic reading is emphasized as a way to prepare students for university-level texts.

To determine whether your students need help with this type of academic reading, do a quick assessment by asking them to discuss a

literary text and determine whether their responses focus on their own personal experiences or the text itself.

The SAME Skills Are Emphasized in Fiction and Nonfiction Texts

In the Common Core, the skills for reading literature and nonfiction texts are the same. They both share the same ten anchor standards.

This helps to deepen reading skills because students are asked to bring the same skills to various texts. In the CCSS, sometimes the

standard is exactly the same and sometimes it is slightly different. For example, in the sixth grade, anchor standard 1 is worded exactly

the same for literature and informational texts because this is appropriate:

Cite textual evidence to support analysis of what the text says explicitly as well as inferences drawn from the text (p.27).

On the other hand, anchor standard 3 is phrased differently for literature and informational texts because this makes more sense.

For reading literature: Describe how a particular storys or dramas plot unfolds in a series of episodes as well as how the

characters respond or change as the plot moves toward a resolution (p.27).

For reading informational texts: Analyze in detail how a key individual, event, or idea is introduced, illustrated, and

elaborated in a text (e.g., through examples or anecdotes) (p.27).

3 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

The Common Core calls for the following distribution for what students should be reading. Note that this does not mean the Common

Core emphasizes nonfiction more, it simply shows that reading should be the responsibility of non-English classes as well:

50% literacy texts and 50% informational texts at fourth grade

45% literacy texts and 55% informational texts at eighth grade

30% literacy texts and 70% informational texts at twelfth grade

Implications for Implementation of the CCSS in Reading

(1) Teachers may need training in how to read using high-level comprehension and analytical skills themselves

Some of the new analytical skills required to meet the CCSS are high level, university skills and it may be necessary to have teachers

practice these skills themselves for professional development, perhaps by doing some shared readings and analyzing them together.

(2) Teachers will need to ensure they have the type of texts students can use to practice synthesizing and critical reasoning

In order to do the more challenging work the CCSS requires analyzing craft, structure, symbolism, and thematic development

teachers can no longer rely on excerpts, anthologies, and textbooks alone so they need to expand their libraries.

(3) Social studies and science teachers will need professional development on reading instruction

School leaders will now need to involve social studies and science teachers in professional development about nonfiction reading

instruction as well as find ways for these teachers to collaborate with strong ELA teachers and look at student assessments together.

Chapter 3 Literal Understanding and Text Complexity: Standards 1 and 10

Text Complexity (Standard 10)

Text complexity lies at the heart of the CCSS although it is specifically spelled out in reading anchor standard 10 which asks students

to read and comprehend complex literary and informational texts independently and proficiently (p.32). For the last several years

there has been too much emphasis on decrying that students have deficits in reading skills such as identifying the main idea, defining

words in context, and other reading skills. For example, a spreadsheet is created showing a student missed the last four questions on a

test and the teacher is told this student needs work in identifying the main idea. However, what if those questions pertain to a

challenging passage and the real problem is that the student isnt prepared for this high reading level? The CCSS tell us that we need

to do more than drill students in reading skills. We also need to raise the level of text complexity that students are able to comprehend.

Literal Comprehension (Standard 1)

In order to understand texts of increasing complexity (standard 10), students need to be able to improve their literal comprehension

(standard 1) which asks students to [r]ead closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it

(p.33). Note that there are two parts of comprehension to understand the explicit meaning and what is inferred. Together, standards 1

and 10 form the foundation of reading comprehension and for this reason are addressed first in this chapter. In order for students to

increase the level of text complexity they are able to read, they must first understand what they are reading! Text complexity and how

it relates to literal comprehension brings up complicated questions when dealing with the CCSS, three of which are explored below.

How do the CCSS suggest educators determine a texts level of complexity?

The CCSS contain a lot of detail about defining text complexity. However, in summary, the standards do not (no matter what anyone

tells you) state that one system of measurement is sufficient and in fact, there are limitations to all current text leveling systems. What

the CCSS do stress is that it is vital for teachers to move students toward ever increasing levels of text complexity. If you want to learn

more about determining text complexity you can look at Appendix A in the CCSS. Teachers do not always have to run to existing

systems such as the Fountas and Pinnell leveling system and can determine text complexity themselves. Below is a brief overview of

the three measures the standards view as the most important to determine text complexity:

Qualitative Measures: To judge text complexity teachers can ask: Are the meanings explicit or implicit? Is the structure conventional or

unconventional? Is the language literal, figurative, or domain specific? Are the knowledge demands everyday or highly specialized?

Quantitative Measures: In addition to qualitative measures, teachers can help judge text complexity by also using computer programs to

examine word length, frequency, sentence length, and text cohesion. Existing systems that do this include the Flesch-Kincaid test, the Dale-

Chall Readibility Formula, and the Lexile Framework for Reading.

Reader and Task Consideration Measures: The third measure requires that educators use their professional judgment to look at the role

that prior knowledge and motivation play in a students comprehension of a text.

What are the standards suggestions for grade-level-appropriate texts?

Teachers will naturally wonder, What level of text complexity is supposed to be grade-level appropriate for my students? The CCSS

response to this is not entirely clear. However, there are two sources that may help teachers in answering this question.

Look at the Grade Bank Exemplar Texts in Appendix B for Help: Appendix B in the CCSS contains a list of exemplar

texts and their approximate range of text difficulty. However, there are several problems here. First, the books cited often represent a

range of grade levels. Also, there is a much greater representation of classic texts than contemporary childrens books in this list.

Look at the Lexile Levels Chart for Help: Appendix A in the CCSS provides recommended Lexile levels. For example,

complex texts in grade levels 2 and 3 should fall within the 450-790 range. However, teachers should use more than one system.

4 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

What does the CCSS say about the implications for instruction?

Step 1. Take stock of your students current reading levels. Before you can help students read high-level texts in order to meet the

CCSS in reading, you need to know what their current reading levels are. If teachers have been trained to assess readers using the

DRA, QRI, F&P, or other methods, then youre set. If not, teachers can circulate and listen for fluency (one of the best indicators of

comprehension) or use other methods mentioned previously in this chapter.

Step 2. Accelerate students progress up reading levels. To accelerate student reading levels, students must read a lot. It also helps

for teachers to have a clear, written plan for how each student will progress. This plan should be shared with the student and it might

sound like this, On the first of October, lets give the Amber Brown (level N/O) books a try because if you read up a storm between

now and then and if you really turn your mind on high to think about these books, I bet you might just be ready to tackle that level of

book by then (p.44) It helps to have an extremely clear target (Level R, for example), provide feedback on the students progress,

and reassess often. A principal can help to keep tabs on this by asking, How many readers in each of my four fourth grades are now

reading at or above the expected benchmark for that grade? and by asking teachers to enter this data into some type of web-based

software program (such as Assessment Pro or Goodreads). However, it is important that teachers provide scaffolding to help students

read more complex texts by introducing the characters or setting in certain books or having students read books in partnerships.

Step 3. Devise a plan to improve students progress toward reading more complex texts. One suggestion is that teachers select a

small number of Common Core complex texts for the entire class to read in unison over two to three weeks and then spend four to five

weeks on six to seven shorter texts (e.g., the Declaration of Independence). It is important that all students even those who are

struggling read these complex texts with the class. Research shows that this type of close reading benefits all students, even those

who are behind. We cannot continue to give those who are below grade level only less complex texts.

Step 4. Implement your plan. Research shows the value in assessing your students reading levels and matching them to texts that

they can read with 95% accuracy. In order to do this, schools need to provide teachers with a larger number of books (at a minimum,

20 books per student), and make sure students have choice among high-interest books. Finally, it is invaluable to organize the school

day to provide substantial time for students to read, talk, and write about their reading. Some research suggests students should have

one and half hours a day to read in school.

Chapter 4 Reading Literature: Standards 2 - 9

Standards 2 9 assume that literature is about much more than plot. Even for young readers, the CCSS emphasize that reading should

lead to a deeper understanding of characters and lessons about themes such as integrity, courage, and determination. The books

authors respond to this emphasis by writing, Thank goodness. For too long, the focus of NCLB and concurrent high-stakes testing

has been on decoding and on readers demonstrating low-level inferences with small chunks of text. (p.52) For this reason, reading

did not improve during the years of NCLB. After starting by focusing on comprehension (as was outlined in standards 1 and 10), this

chapter focuses on higher levels of analytical work as is described in standards 2 9. Below is an overview of these anchor standards.

Reading Literature for Key Ideas and Details Standards 2 & 3

Standard 2. Determine central ideas or themes of a text and analyze their development; summarize the key supporting details and ideas.

Standard 3. Analyze how and why individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of a text. (p.54)

These standards address are the ability to summarize, to connect different parts of a text, to infer ideas and themes, and to trace the

development of individuals, events and themes. This may be a challenge to students who are used to simply focusing on the words on

the page. Now they need to carry meaning and understanding with them throughout the story and be able to infer and answer why

questions. Furthermore, students now need to think about the central message or moral. This does not mean teachers should teach the

moral of the story but rather help students develop the habit of thinking, What did the main character learn that I, too, could learn?

Reading Literature for Craft and Structure Standards 4, 5, & 6

Standard 4. Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative

meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

Standard 5. Analyze the structure of texts, including how specific sentences, paragraphs, and larger portions of the text (e.g., a section,

chapter, scene, or stanza) relate to each other and the whole.

Standard 6. Assess how point of view or purpose shapes the content and style of a text. (p.58)

If the above two standards focus on what the text says, these three focus on how it says it. These three standards focus on how the

authors decisions about craft about language, structure, point of view, voice, style affect the meaning of the text. Reading for craft

and structure can be done even at the youngest age. We dont need to wait for The Scarlet Letter to address the concept of symbolism.

Even the youngest readers can think about point of view and why two characters might view the same situation differently. As

students get older, without paying attention to craft and structure, readers will not be able to fully grasp the meaning of many texts.

For example, first graders can read Poppleton for plot alone, but once students get to The Giver, it is impossible to read this book for

plot alone and truly comprehend its meaning. Literal comprehension only constitutes partial comprehension of many advanced novels.

5 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

Reading Literature to Integrate Knowledge and Ideas Standards 7, 8, & 9

Standard 7. Integrate and evaluate content presented in diverse media and formats, including visually and quantitatively, as well as in

words.

Standard 8. Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the

relevance and sufficiency of the evidence. (Not applicable to literature)

Standard 9. Analyze how two or more texts address similar themes or topics in order to build knowledge or to compare the approaches

the authors take. (p.62)

These standards are about relating ideas across texts. For nonfiction this might involve reading more than one text on a topic and for

fiction it might involve comparing a novel to a movie or looking at how two different novels address the same theme. Again, even

though this standard is eventually preparing twelfth graders for what comes next, it is easily applicable to even the youngest readers.

First graders can compare characters, read all Poppleton books (for example), or read a number of books by the same author and

compare them. As they get older it is easier to imagine students comparing the movie versions of The Hunger Games and Twilight to

the texts and determining which formats are more effective.

Pathways for Implementing the Literature Standards 2 9

1. Conduct a Needs Assessment In order for students to read at the level required by the CCSS, it is important first to know where

your students are with their analytical reading skills. Reading records may not be enough to determine if students are capable of using

higher-level reading skills. However, you dont need a leveling system, you can assess higher-level comprehension yourselves. Simply

choose a few books to use to assess students, read those books yourself, and determine the intellectual work you find yourself doing

while reading them. Write questions in the margins you can use to assess higher-order skills. Then have students read the text and

meet with them one-on-one to ask these questions to determine the level of intellectual work of which they are capable.

2. Align Teaching Methods and Content It will take a lot of work to get students to reach the higher reading levels required by the

CCSS. Currently many elementary teachers use core reading programs or basals and these reading programs have not produced

strong readers. In upper grades teachers often teach longer novels and many students are able to hide in whole-class discussions so

teachers dont know if students can independently do high-level work on their own. Teachers at the secondary level may demonstrate

higher-level reading skills to students, but they often dont take the next step to coach students and provide feedback while students do

this work on their own. In order for teachers to move more in this direction, below are some suggestions:

a. Students should do a lot of in-school reading Students learn to read by reading and receiving feedback which both take

time. To move students up reading levels schools need to manipulate schedules and teachers need to ensure that time is set aside for

reading and feedback. Thousands of schools have increased in-school reading time and shown tremendous reading progress.

b. Students should choose from a wide variety of high-interest books Teachers can ignite student interest in reading by

talking up books, carrying around high-interest books, introducing books in mini-lessons, and seeming obsessed by reading.

c. Students need explicit instruction in higher-level reading skills Teachers need to demystify what it means to do more

serious intellectual reading work. Beyond demonstrating these skills, teachers need to break these skills down into steps, and provide

ample time for students to practice and receive feedback repeatedly until they can perform the skills independently.

Chapter 5 Reading Informational Texts: Standards 2 - 9

From the beginning of the document, the CCSS stress the importance of nonfiction reading. However, this is not the type of reading

that is just about pulling out facts. Instead, it aims to prepare students for the type of nonfiction reading expected in college reading

to analyze the authors reasoning, evaluate the authors claims, determine the sufficiency of the evidence, and reveal the authors point

of view. While there are standards for reading informational texts in science, social studies, and technical subjects, this chapter focuses

on the nonfiction reading standards in the ELA section of the CCSS. Like the standards for reading fiction, the informational reading

standards share the same grid with ten anchor standards, the only difference being the type of comprehension required.

Reading for Key Ideas and Details -- Standards 1-3

These standards provide the foundation for the rest of the informational text standards. Standard 1 focuses on the ability to read

closely to determine what the text says explicitly (p.77). This is not about students having a personal response to the text. Rather, it

focuses on whether students get the text. Can students read a nonfiction text and then turn to someone else and teach that person

everything learned so far? Next, standard 2 is about determining central ideas. Can students answer the question, What is this text

starting to be about? and What specific details support this central idea? The third standard asks readers to analyze how

individuals, events, and ideas develop and interact over the course of the text. (p.81) This standard is about noticing the sequence of

events as well as the development of relationships and noting cause and effect in a text. For any of these first three standards, students

may need to go back to the text and re-read to find missed details or meaning as well as to look for evidence to support their claims.

6 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

Reading for Craft and Structure -- Standards 4-6

These standards, like for fiction, are about how a text is written that is, how the craft and structure affect a texts meaning. Standard

4 focuses on how the technical, connotative, and figurative meaning of words affect meaning. Students need to be able to look at the

words used in a text and determine their connotation. Furthermore, what types of words are used biblical, apocalyptic, poetic? Do

the words suggest dread, sympathy, or distaste? For example, if students read Lincolns Gettysburg Address closely they will see the

use of religious terms to convey that the country is engaged in a sacred mission. Standard 5 focuses on the structure of the text. To

help students analyze structure, teachers can have students look back over the text and determine what type of meaning is being

conveyed in different paragraphs. For example, an introductory paragraph might serve as a mini-lecture while the following

paragraphs may introduce gripping anecdotes that serve to induce sympathy. Then the tone of the piece might change to convey a

larger theme in the text. Standard 6 focuses on how the authors point of view affects the text. Students should be able to answer,

How does the choice of words, the tone of the language, illuminate the authors point of view on the topic? (p.85)

Reading Informational Texts -- Standards 7-9

To work on these standards, students will need an additional text because standard 7 asks students to integrate and evaluate content in

different media. Students should be able to develop a more nuanced view of the first text by looking at a second text, movie, or some

other format. In standard 8, students need to evaluate the soundness of the authors claims and evidence. Finally, standard 9 asks

students to compare two texts on the same subject to determine how each text presents similar claims.

IMPLEMENTING the Informational Text Standards

Challenges in Implementation

Before implementing the informational text standards, consider whether your school faces any of the common obstacles below:

Students arent reading enough nonfiction: For K-8, 45% of students academic reading should consist of informational texts, and the

percentage is even higher for high school. Currently, this is rarely the case. An average fourth grader reads about 25 pages of fiction a

day but only two pages of expository text a day. Figure out how many pages of expository text your students read a day.

Students arent reading just-right informational texts: Most of the informational texts students read are either too hard or too poorly

written to engage them. Have students read some nonfiction texts aloud and listen for fluency to see if this is true for your students.

Students have no choice over informational texts: Think of the blogs, newspapers, or books about your hobbies that you read. Students

will be more engaged if they have choice over their informational texts as well.

Overcoming Obstacles in Implementation Suggestions for improving informational text reading

Get more high-interest nonfiction books: There isnt a classroom in the US that has a nonfiction library that rivals that of the

fiction books in the classroom. Although budgets are tight, it is imperative to find a way whether through grants; less expensive DK

Readers; inexpensive journals like Junior Scholastic; online sources such as PBS, Discovery, or

readingandwritingproject.com/resources/classroom-libraries/archive.html to increase the number of nonfiction texts in class

libraries. For guidance on the types of texts to acquire, there are text exemplars in Appendix A and B of the CCSS.

Infuse more information reading into content-area classes: Because the amount of nonfiction reading in the CCSS is most

likely much higher than what you currently have, non-ELA teachers need to help by teaching nonfiction reading as well.

Match students to nonfiction texts: Even if you acquire more nonfiction books and give students choice, you will not succeed

unless students are matched with the appropriate nonfiction level. A student cannot begin to engage with the central ideas in a text if

she can barely understand it. While many schools already have leveling systems for fiction books, there are no consistently reliable

systems for leveling nonfiction texts. For this reason, teachers should feel confident in doing the leveling themselves. However, keep

in mind that your students will likely be less experienced expository readers, so you should teach them how to find more introductory

books on their topics and not to be fooled by pictures and captions which dont necessarily mean the text is easy to read.

Explicitly teach higher-level reading skills: Most students are used to reading informational texts at the most basic level --

just to gather facts. However, the CCSS require that students achieve a much higher level of reading. For example, if a student reads

about Gettysburg and can regurgitate the number who died but fails to understand the significance of the battle as a turning point in

the Civil War, then this student needs to learn higher-level reading skills.

Chapter 6 -- OVERVIEW of the WRITING STANDARDS

In contrast to NCLB where writing was not even mentioned, the CCSS have a tremendous emphasis on writing. Below is an overview.

Three Types of Writing

More than half of the pages covering the writing standards focus on three types of writing expected of students: (1) argument, (2)

informative/explanatory, and (3) narrative writing. For each of these types of writing, the CCSS provide guidance by including a K-12

progression of skill development as well as exemplar texts that show what the students writing pieces might look like. The CCSS

make it clear that the responsibility for teaching writing belongs to all teachers including math, social studies, and science. The next

three chapters focus on these three types of writing. Many of the types of writing students currently do fit into these three categories:

7 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

Narrative Writing: personal narrative, fiction, historical fiction, fantasy, narrative memoir, biography, narrative nonfiction

Persuasive/Opinion/Argument: persuasive letter, review, personal essay, persuasive essay, literary essay, historical essay, petition,

editorial, op-ed column

Informational and Functional/Procedural Writing: fact sheet, news article, feature article, blog, website, report, analytic memo,

research report, nonfiction book, how-to book, directions, recipe, lab report

The Writing Process

Standards 1-3 focus on the three writing types above, but the later writing standards show how to go about doing the work of these

standards. For example, the importance of the writing process is emphasized in several standards. Standard 5 focuses explicitly on the

writing process and says that students should be able to develop and strengthen writing as needed by planning, revising, [and]

editing (p.105). Standard 10 covers the need for students to write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection,

and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) (p.105). These challenging standards necessitate that students

develop a habit of writing. And not just any kind of writing, but a structured approach to writing in which students know how to

approach writing with time for planning, drafting, revising, etc. Furthermore, the standards are specific about volume for example,

fourth graders need to be able to write one typed page in a sitting while in fifth grade this jumps to two pages in a sitting.

The Quality of Student Writing

Its obvious that the writing standards call for an extremely high standard of writing quality. Just take a look at the sample pieces of

writing all students are expected to do in Appendix C. These high expectations are conveyed in standard 4 which states that students

are expected to produce clear and coherent writing in which the development and organization are appropriate to task, purpose, and

audience (p.107). The emphasis in the standards is not on developing voice and vividness but rather on clarity and structure.

Writing as Integral Even for Very Young Students

In the vast majority of schools, kindergarten is a time for socialization and learning the alphabet. The CCSS are explicit in their

opposition to this view: even the youngest students can write long, well-developed texts, with fluency and power. Rather than the

current approach in which kindergarteners only write stories and older students only write essays, the CCSS expect that the youngest

students should be engaging in the type of writing that will lay the foundation for later years: writing their opinions, supporting these

opinions, drafting, revising, editing, publishing and more. Schools need to develop a spiral curriculum in which, for example, students

write opinions in the early grades, structured arguments in middle school, and contextualized arguments that are carefully researched

and anticipate counterarguments by high school.

Writing Across All Disciplines

The CCSS require that all teachers are teachers of writing. To convey this message, the CCSS refer to the writing standards as a

shared responsibility all teachers in every content area and every discipline, need to teach writing to students.

Implementation Implications of the Writing Standards

While not every school has emphasized the teaching of writing, those that have, most often turn to the writing process as the approach

that is most effective for teaching writing. The Common Core writing standards are completely aligned to the writing process

approach with a few new areas to focus on and an increase in the expectations for the quality of writing students must produce.

Chapters 7 9 The CCSS and Composing Narrative, Argument, and Informational Texts

The authors spend an entire chapter on each of the three types of writing above. However, below are some shared characteristics of

these three types of writing that are important to note as well as some highlighted information about each of the three.

Important Aspects of the Three Types of Writing in the CCSS

The Expectations for the Writing Standards are AMBITIOUS

If teachers only look at the descriptors for the writing standards in the grade level they teach, they will likely panic. The writing

standards are high particularly for narrative and argument writing. For example, below is an excerpt from the middle of a fourth

grade narrative piece of writing (one of the exemplars in Appendix C) and it shows that even at nine years old, students are expected

to do a lot more than write mere accounts. They are expected to write well-crafted, tightly structured stories. Note that this piece was

produced independently by a fourth grader on demand. It is a very skilled piece of writing that includes specific detail, builds tension,

and effectively includes dialogue. Only part is excerpted below:

One quiet, Tuesday morning, I woke up to a pair of bright, dazzling shoes, lying right in front of my bedroom door. The shoes were a nice

shade of violet and smelled like catnip As I walked on, I observed many more cats joining the stalking crowd. I moved more swiftly. The

crowd of cats walk turned into a prance. I sped up. I felt like a rollercoaster zooming past the crowded line that was waiting for their turn as

I darted down the sidewalk with dashing cats on my tail. (p.114)

The writing standards are rigorous. Students are expected to write well-crafted, tightly structured stories for narrative writing, argue

and support claims and even anticipate counterarguments in argument writing, and organize facts, information, ideas, and concepts in

informational writing. However, it is important to note that the CCSS in writing are laid out in a way to help teachers help students

meet these challenging standards. While reading the expectations for fifth grade alone might stun teachers, if they begin by reading the

8 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

kindergarten writing standards and then read through the standards horizontally grade by grade they will see that in fact, teachers

are not asked to work miracles. Instead, there is an incremental skill progression from grade to grade that is reasonable.

The Writing Standards Lay Out Helpful Learning PROGRESSIONS

Again, if you only look at the writing standard descriptors for the grade you teach, they will seem unrealistically ambitious. Instead,

start by reading the grade level skills required for kindergarten and imagine the type of story, opinion piece, or informational text a

five-year-old would need to write to meet these expectations. Then read the additional expectations for first grade and again imagine

an accompanying piece of writing. Continue reading the grade level standards horizontally noting the incremental additions at each

grade. This will help you understand the progression of skills that lead up to your grade level. For example, for narrative writing

kindergarteners are asked to narrate a single event and provide a reaction to what happened. Imagine a stick figure drawing of a roller

coaster with a person on it and the student writing, I rode the roller coaster. I was scared. Then by second grade, the

standards call for students to elaborate, include details for actions, thoughts, and feelings, and provide closure. This time you might

imagine, I got on the roller coaster. I was scared. My stomach felt sick. It went up the hill. I was more

scared. I thought about accidents. I wanted to cry. We got closer to the top then we raced down and up and

around. I was afraid I would be sick. I was sick. But I was alive and it was over. The authors show how the

expectations rise for narrative writing again in grade 4, then in grade 8, and finally in grades 11-12. They also provide examples of

roller coaster stories that might accompany each of these progressive standards.

Another good idea the authors present is to underline just the new words that each grade level expectation contains. This will help

teachers understand which skills to focus on for their grade level. Below is an example for informational texts for a few grades:

Writing Standard Kindergarten: First Grade: Second Grade:

1 Use a combination of drawing, dictating,

and writing to compose

informative/explanatory texts in which

they name what they are writing about and

supply some information about the topic.

Write information/explanatory

texts in which they name a topic,

supply some facts about the topic,

and provide some sense of closure.

Write informative/explanatory texts in

which they introduce a topic, use facts

and definitions to develop points, and

provide a concluding statement or

section.

The Skills Learned for One Writing Type Can Be TRANSFERRED TO THE OTHER TYPES OF WRITING

Another helpful aspect of the writing standards is that the approach to narrative, persuasive, and informational writing (anchor

standards 1 3) is the same. For example, the first descriptor for each of these three describes how writers should begin their texts.

Although the specifics differ, the overall idea is that whether a student is establishing a situation, orienting the reader, creating an

organizational structure, or establishing a focus these are all variations, based on the type of writing required, on what students need

to do to begin writing a text. The next descriptor addresses how writers should develop their pieces of writing (by elaborating, using

details, etc.). And for all three types of writing, students must create some type of closure to the piece. This is helpful because once

you have taught students how to begin one type of text (e.g., a narrative text) you can be more efficient in teaching students how to

begin the other types of writing (a persuasive or informational text) by reminding students of the skills they have already learned.

Some Specific Information about Each Type of Writing

NARRATIVE Writing anchor 3 addresses narrative writing. Students are expected to: Write narratives to develop real or imagined

experiences or events using effective technique, well-chosen details, and well-structured event sequences (p.114) It may help

teachers to look at the narrative writing standards first and even teach these first since many English teachers are more comfortable

with this type of writing. In general humans have been brought up on stories it is our primary way of knowing. Think about TED

talks youve seen -- strong models of persuasive and informative writing and note that most are powered by stories! Chapter 7

focuses on writing narrative texts and you can see how the narrative writing standards develop from grades K 12 with the roller

coaster example (excerpted above) and from the additional roller coaster narratives in the chapter of the book itself.

ARGUMENT/OPINION The standards for writing argument texts may be the most ambitious of all and may be where teachers

have the most new work to do. Argument writing is a big deal in the CCSS and this is obvious from its placement as standard 1.

Students are asked to: Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and

relevant and sufficient evidence. Because university life is made up of an argument culture and the CCSS were mapped backwards

from college, it is understandable that argument writing would have such a prominent role. Furthermore, by helping students improve

their argument writing, these standards will lead students to improve their thinking, learning, and researching skills. By teaching

students to write argument pieces teachers will be teaching them to look for various sides of an issue, weed out bias, weigh evidence,

track the development of ideas, consider whether a source is trustworthy, and a number of other vital critical reasoning skills that

make it clear that the Common Core prioritizes critical judgment even at the youngest ages!

INFORMATIONAL

In the informational writing standards, the CCSS call for students to Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey

complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content. Basically

these skills are about students developing the skills to think about the subject areas, books, and life. In informational writing, there is a

9 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

strong emphasis on text organization and structure. In the primary grades this is more basic, focusing primarily on naming a topic,

developing an idea, supplying facts, and conveying ideas clearly. By grades 11-12 students are expected to: Introduce a topic;

organize complex ideas, concepts, and information so that each new element builds on that which precedes it to create a unified

whole (p.148). This is fairly short for the upper grades and is meant to convey that the skill of organizing information like sorting a

pile of laundry should take precedence over the other aspects of informational writing.

The CCSS seem to call for a much greater percentage of writing to be informational and this has worried English teachers. If you

pause for a moment you will realize that students already do a tremendous amount of informational writing such as: research reports,

lab reports, summaries in response to reading, math records, Post-it notes, etc. However, because writing done in science, art,

computers, social studies, and math counts for informational writing time this means that ELA teachers do not need to replace their

entire curriculum with all informational writing all the time! What will be new is not spending more time on informational writing but

rather raising the level of craft of informational writing to that already employed in narrative writing. Most of the time teachers have

students writing informational pieces to prove they have read something or gained some new knowledge. Now with the CCSS,

students informational writing will be held to the same standards as their essays and short stories!

Pathways for Implementing the Writing Standards

The Writing Process Approach

In the authors experience, when they have seen students not progress in their writing it is because no actual writing occurs in school.

Students are given a writing assignment and perhaps even some instruction, but the actual work of doing the writing happens outside

of school. Students need structured time in classrooms to practice their writing and they need regular feedback from teachers. The

most effective way teachers have accomplished these two items is through the writing process approach. Schools that do not yet use

this approach are strongly urged to launch it to help them implement the writing standards. This way students can develop the type of

habits such as drafting, revising, and getting feedback that will boost the level of their writing. If there are classrooms in your school

that already use the writing process, those teachers should open their classrooms for all teachers including content-area teachers to

observe. That way even science teachers can see the benefit of students revising their lab reports in response to feedback that comes

with the writing process approach. There is a list of writing workshop resources on p.126 of the book for help launching this approach.

Align Instruction and Use a Common Learning Progression

Teachers need a common understanding of what is expected of student writing from grade to grade. To achieve this, put together

teams of teachers (at the same grade level and across grades) to study the descriptors of grade level skills in the writing standards (and

the exemplars where available) and map out the skills, and units that teachers will all teach at each grade level. This will ensure

consistency in the writing skills students learn each year. Imagine a grid with rows and columns that outline, for each of the three

types of writing, which genres and which skills would be taught in which grades. For example, for informational writing the following

genres might be taught in the following grades: all-about books in second grade, informational nonfiction chapter books in third grade,

investigative feature articles in fourth grade, research reports in fifth grade, and so on.

The authors also suggest that teachers collect exemplars of student work at each grade level against which student work can be

assessed. Or they can use the continuum of student writing that has already been compiled by the Teachers College Reading and

Writing Project which is aligned to the CCSS. It is available for free at: www.readingandwritingproject.com. These exemplars can be

used to compare against students writing to determine their progress.

Chapter 10 Overview of the SPEAKING and LISTENING and LANGUAGE standards

This section focuses on the last two components of the ELA standards: speaking and listening and then finally language. While these

may feel like more of a burden and more work for teachers, done well, they can be incorporated into the rest of instruction.

Speaking and Listening Standards

You will notice that the speaking and listening standards are more prominent in the CCSS than in most state standards where in fact,

they are largely ignored. The authors wanted to make sure that students would be prepared to have the types of intellectual

conversations expected in college by the time they get there. In this section there are six anchor standards: the first three of which

focus on students conversing with each other to understand texts while the second three focus on students making oral presentations:

Comprehension and Collaboration

1. Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others ideas and

expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

2. Integrate and evaluation information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

3. Evaluate a speakers point of view, reasoning, and use of evidence and rhetoric.

Presentation of Knowledge and Ideas

4. Present information, findings, and supporting evidence such that listeners can follow the line of reasoning and the organization,

development, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

5. Make strategic use of digital media and visual displays of data to express information and enhance understanding of presentations.

6. Adapt speech to a variety of contexts and communicative tasks, demonstrating command of formal English when indicated or appropriate.

10 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

Like with the reading and writing standards, the expectations are high, but if teachers read horizontally through the grade by grade

standards, they will see that the standards only call for a reasonable amount of incremental progress each year. A few notes are

important in the speaking and listening section. First, be careful because unlike in the reading and writing sections where the authors

stay away from prescribing specific instructional approaches and focus entirely on expectations, this section does veer more into

making curricular suggestions. Also note that speaking is more broadly defined to include nonverbal communication and listening to

include multimedia as are outlined in anchor standards 2 and 5 above. While the CCSS do not specify exactly what type of technology

you must use, they make the bold statement that students must become savvy in understanding and creating media. However, it is

clear that this is not technology for technologys sake, but it is technology to help students become better communicators.

Because there are rarely any high-stakes tests in speaking and listening, you will be able to implement these standards as you see fit.

The authors suggest that in order to achieve the type of high-level discussions among students demanded by these standards, teachers

will need to be purposeful about planning these discussions and how they will develop throughout the year. Furthermore, by being

strategic, teachers can address other standards at the same time. For example, while having students follow a Common Core-aligned

reading curriculum, teachers can also have students follow the first three speaking and listening standards by beginning the year with a

one-to-one reading partnership where students read the same book in pairs and in that safe and small environment of only two students

practice the speaking and listening skills they will apply to larger groups later on in the year. Your goal is to release more and more

responsibility so that students learn to speak and listen independently without your help.

Language Standards

There are six anchor standards for language divided into three categories:

Conventions of Standard English, which outlines expectations for grammar

Knowledge of Language, which outlines how students should apply their knowledge of language as craft choices in their

writing and speaking

Vocabulary Acquisition and Use, which outlines expectations for vocabulary

The CCSS emphasize a few important points about the language standards. First, the language standards should not be taught in

isolation. That is, a student should not be taught to memorize what a simile is, rather a student should be able to apply and use the

knowledge of rules or definitions. Second, the language standards are lean. Rather than spiraling a skill throughout the grades so that

the upper grades have longer and longer lists of skills to cover, each grade mostly has its own set of skill expectations. Finally, the

authors acknowledge that what is acceptable in terms of language use and what is not acceptable changes over time.

As far as implementation goes, beware of the Common Core-aligned workbooks for grammar or vocabulary. The point is to make

students independent users and appliers of language, grammar, and vocabulary. Therefore, teachers should respond to individual

student needs in the context of their reading and writing and not purchase a set of prepackaged and disconnected ditto sheets. Teach

the language standards in connection with the writing, reading, speaking, and listening standards.

Chapter 11 Final Notes on Assessments and Implementation Implications of the CCSS

Assessments and the Common Core State Standards

The truth is that whatever skills are assessed in state tests are the skills that teachers emphasize. Or, as the authors phrase it, in the US,

the tests are the tail that wags the dog. In the past these tests have not assessed complex literacy skills such as the ability to write

essays, compose compelling narratives, read critically, and other high-level literary skills. For this reason, teachers have not, for the

most part, taught these skills. As a result, student literacy has suffered. Now two groups are working to develop Common Core-

aligned assessments (PARCC Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers and SMARTER Balanced) that

have the potential to assess higher-level thinking, reading, and writing. However, these have not yet been developed and in the

meantime schools need to rely on their own resources.

Some Final Notes About Implementation Implications of the CCSS

A word of caution to school leaders who may respond to the new expectations of the CCSS by trying to shove more into an already

crowded school program dont! Research shows that this is not effective. Instead, it is far more effective to study what it is that

teachers are already doing that matches the priorities of the Common Core. Figure out how to bring everyone on board with these

existing initiatives and then find ways to invest in doing that work more deeply. The idea is to broaden and deepen what already works

and what already supports the Common Core. Research suggests that as little as 20% of what goes on in schools is responsible for

80% of the outcomes. However, schools often dont succeed because people are not willing to give up most of their teaching practices.

Instead, think about what might be the high-impact, Common Core-aligned practices at your school. Then encourage teachers to

observe those practices, plan together, and adopt shared teaching methods. The high-impact, Common Core-aligned practices in one

classroom can soon become school-wide shared practices.

11 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

Professional Development Suggestions from THE MAIN IDEA

Based on the ideas in the book and the Common Core State Standards themselves, below are workshop ideas for a facilitator to use

with teachers. There is A LOT here. Dont be overwhelmed just pick and adapt what works for you. Below is an overview so you

know whats coming:

I. INTRODUCE THE STANDARDS

A. Discuss preconceived notions about the CCSS

B. Discuss what is golden about the standards

II. STUDY THE STANDARDS

A. Study the organization of the CCSS

B. Study the high levels expected in the CCSS

C. Study the reading standards by practicing the reading skills themselves

D. Study the writing standards by identifying writing skills in actual pieces of student writing

III. BRIEFLY ASSESS WHERE YOU ARE WITH THE STANDARDS

A. Assess areas of alignment between the CCSS and your reading instruction

B. Assess areas of alignment between the CCSS and your writing instruction

IV. PLAN TO IMPLEMENT THE STANDARDS

A. Agree on common skills, genres, units, and texts

B. Know where your students are and chart their progress

C. Set goals to accelerate your students progress

I. INTRODUCE THE STANDARDS

A. Discuss preconceived notions about the CCSS

1. In pairs, ask teachers to discuss what some of their initial impressions of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) are.

2. Ask for some volunteers from these pairs to share their ideas with the larger group and discuss these impressions.

B. Discuss what is golden about the standards

1. After this discussion, acknowledge that there are legitimate concerns and much that is unknown about the actual implementation of

the CCSS, but there is a great deal of potential for the standards to raise the level of literacy instruction across the US in ways that will

deeply benefit all students if we focus on what is golden about the document. Hand out the following and discuss:

What is golden about the Common Core State Standards?

The CCSS provide an urgently needed wake-up call: The world has changed. Twenty-five years ago 95% of our jobs required lower-level skills.

Today, only 10% of our economy consists of low-skills jobs. New levels of literacy are essential in todays world and yet students leave schools

without strong literacy skills.

The CCSS emphasize a much higher level of comprehension skills: The CCSS are replacing NCLB which held phonics on equal par with

comprehension. With one glance at the CCSS you can see that this document places a much stronger emphasis on higher-level comprehension. For

example, even younger students are expected to find similarities and differences in points of view and to analyze various accounts of an event. This is

a far cry from the previous focus on basal reading programs and seatwork under NCLB.

The CCSS increase the emphasis on writing: With NCLB there was NO mention of writing. Now the CCSS place equal importance on both

reading and writing.

The CCSS are clear and succinct: In many states, educators are used to an overwhelming number of standards. In contrast, you have to admire the

clean, coherent design of the CCSS. The document itself says that standards should be: high, clear, and few, and the CCSS meet these criteria. There

are 10 anchor standards in reading and 10 in writing and these are rolled out in grades K-12.

The CCSS acknowledge that growth occurs over time: The CCSS send a clear message growth takes time. Teaching a skill is never solely the

responsibility of the fourth or the tenth-grade teacher. For example, with reading anchor 2 (determining central ideas of texts and analyzing their

development) there is a progression of skills needed to meet this standard in each grade. For first graders this means being able to retell a story with

details and for eighth graders being able to analyze how themes develop and interact. This type of progression requires that schools have a spiraled

curriculum in which students develop skills over time. The authors of the CCSS took the skills students need for college and carefully planned

backwards for the skills they would need at each grade level, all the way down to kindergarten, in order to prepare students for college.

The CCSS respect teachers professional judgment: The CCSS state: The Standards define what all students are expected to know and be able

to do, not how teachers should teach. Teachers must rely on their own knowledge to bring students to the ambitious levels outlined in the CCSS.

12 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

II. STUDY THE STANDARDS

A. Study the organization of the CCSS

While teachers may feel the standards seem to go on for pages and pages, you can help them feel less overwhelmed by showing them

that there are really only 10 anchor standards in reading and writing. These ten anchor standards are the same for every grade, its

just that the pages and pages are needed to describe how the complexity of the skills increase as the grades go up.

To show them this simplicity, copy and distribute just the four pages in the CCSS that contain the ANCHOR STANDARDS for reading

and writing (pages 10, 18, 35, and 41). Explain that all the other grade-level specific standards come from these, and give them time to

study these anchor standards.

B. Study the high levels expected in the CCSS

If teachers only look at the descriptors for the grade level they teach they will likely panic because the expectations laid out in the

CCSS seem quite ambitious. However, you can help them feel less intimidated by having them read through the standards horizontally

grade-by-grade to show them that the expected skill progression from year to year is an incremental one. To help make this point,

copy just one page from the CCSS for the grade level they teach, and have them read horizontally across to see that the progression

from grade to grade is manageable. You can copy a page that spans grades K-2, 3-5, 6-8, or 9-12 for them.

This skill progression will not only show teachers that their job is reasonable, but it will also help outline which skills they are

responsible for covering. Following a suggestion from the authors of the book, have the teachers read the skills on the CCSS page in

front of them and underline just the new words each grade level expectation contains. This will help teachers understand which skills

to focus on for their grade level. Below is an example for writing informational texts for a few grades. Share this example and then

have teachers do the same with the CCSS page in front of them.

Writing Standard Kindergarten: First Grade: Second Grade:

1 Use a combination of drawing, dictating,

and writing to compose

informative/explanatory texts in which

they name what they are writing about and

supply some information about the topic.

Write information/explanatory

texts in which they name a topic,

supply some facts about the topic,

and provide some sense of closure.

Write informative/explanatory texts in

which they introduce a topic, use facts

and definitions to develop points, and

provide a concluding statement or

section.

C. Study the reading standards by practicing the reading skills themselves

Some teachers may not have used, let alone taught, the types of higher-order reading skills in the CCSS since college. To truly

understand what the reading standards mean in practice, teachers need to be able to perform those skills themselves first. The books

authors suggest that teachers do a shared reading of a text and discuss it using these skills as practice. They suggest two shared reading

texts one fiction (Charlottes Web) and one non-fiction (a New Yorker article) -- with lots of guidance for how to discuss these texts,

going standard by standard. I would suggest you choose a strong ELA teacher, coach, or department chair to lead a group of teachers,

particularly non-ELA teachers, through this activity. I dont need to provide any additional guidance here because the book provides

plenty of guidance in the form of coaching and questions the facilitator might ask to guide the teachers through a discussion using the

skills in all ten of the reading standards. For guidance with Charlottes Web the facilitator can look at Chapter Four in the book, and

for help with a discussion of the New Yorker article, which can be downloaded online, the facilitator can turn to Chapter Five.

D. Study the writing standards by identifying writing skills in actual pieces of student writing

To help teachers understand what the writing standards mean in practice, they need to be able to look at student writing and determine

whether it meets the levels required by the CCSS. To help teachers (both ELA and non-ELA) deepen their understanding of the

writing standards, try the following activity.

Step 1: Divide teachers into four groups and give them a copied piece of opinion/argument student writing from Appendix C in the

CCSS at either the 2

nd

, 4

th

, 7

th

, or 10

th

grade level to read. You can find the argument pieces in Appendix C on the following pages:

p.15 (for grade 2), p.25 (for grade 4), p.40 (for grade 7), and p. 65 (for grade 10).

Note: DO NOT COPY the annotation that explains how well the students met the writing standards. This is going to be the task for the

teachers. For example, the 4

th

grade argument annotation tells you that the piece, provides reasons that are supported by facts and

details as well as other comments so dont copy this. Let the teachers discover whether the writing meets the standards themselves.

Step 2: Give each group the opinion/argument writing standards for the grade-level student piece they just read. Note that they should

focus on writing anchor standard 1 since this is the standard that covers argument writing. You can copy the appropriate writing

standards from the CCSS for the following pages: p.19 (for grade 2), p.20 (for grade 4), p.42 (for grade 7), and p.45 (for grade 10).

Step 3: Have each group of teachers discuss how well the piece of student writing meets the writing standards for that grade. If

teachers have an easy time doing this with the argument piece, you may want to have them try it with an informative piece. If they

find the task challenging, you may want to show them the annotations written by the CCSS authors that explain how each piece meets

the standards.

13 (Pathways to the Common Core, Heinemann) The Main Idea 2012

hjjyffg.ne..net2009

III. BRIEFLY ASSESS WHERE YOU ARE WITH THE STANDARDS

A. Assess areas of alignment between the CCSS and your READING instruction

The authors clearly warn: Do not respond in knee-jerk fashion to the CCSS by adding a million new initiatives. First look to see what

you already have in place.

1. Which of the reading standards do teachers already address? For which ones will they need the most help?