Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Teacher Reinforcement and Attitude Toward Teacher - An Application of Newcombs Balance Theory

Загружено:

api-301399012Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Teacher Reinforcement and Attitude Toward Teacher - An Application of Newcombs Balance Theory

Загружено:

api-301399012Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Journal cf Educational Psychology

1972, Vol. 63, No. 5, 418-422

PERCEIVED REWARD VALUE OF TEACHER REINFORCEMENT

AND ATTITUDE TOWARD TEACHER:

AN APPLICATION OF NEWCOMB'S BALANCE THEORY1

DEWITT C. DAVISON"

University of Toledo

A 20-item questionnaire representing typical positive and negative reinforcing behaviors of teachers was administered to 256 eighth-grade

students. Subjects responded to the questionnaire twice, once in reference to a "Best Liked" teacher providing the reinforcement and

once in reference to a "Least Liked" teacher providing the reinforcement. Subjects indicated their feelings about the reinforcement by

choosing from among five statements ranging from highly favoraable to highly unfavorable. The significance attached to the positive

reinforcement was related to subjects' attitude toward the teacher,

sex, and social class. The significance attached to the negative reinforcement was also related to subjects' attitude toward the teacher,

but not to sex and social class. The relationship of attitude toward

the teacher and receptiveness to teacher reinforcement was conceptualized in terms of Newoomb's balance theory.

In studying the effects of reinforcement

on behavior, the focus of attention has been

mainly on subjects' overt responses to reinforcement as the behavioral characteristics

of interest. Few investigators have been concerned with individuals' affective reactions

to the stimulus events which are intended

to reinforce their behavior. Yet, how they

overtly respond to these events depends in

part on how they perceive them and the

significance they attach to them.

In the present study, the significance

students attached to certain teacher behaviors which were intended to reinforce

them was examined in relation to their attitude toward the teacher, their sex, and

social-class background. A number of investigators have found subjects' overt responsiveness to reinforcement to be posi-

tively related to their attitude toward the

dispenser of the reinforcement (Ferguson &

Buss, 1960; McCoy & Zigler, 1965; Sapolsky,

1960; Simkins, 1961). The findings bearing

on the relationship of social class to reinforcer effectiveness are generally mixed

(Douvan, 1956; McGrade, 1965; Rosenhan

& Greenwald, 1965; Terrell, Durkin, &

Wiesly, 1959; Zigler & DeLabray, 1962;

Zigler & Kanzer, 1962). And although sex

differences in responsiveness to reinforcement have been observed in a number of

studies (Ferguson & Buss, 1960; Meyer,

Swanson, & Kauchack, 1964; Rosenhan &

Greenwald, 1965; Rowley & Stone, 1964;

Stevenson, 1961; Stevenson, Keen, &

Knights, 1963), these results are similarly

inconclusive, as the sex group found to be

more responsive varied with different studies.

1

This article is based on portions of the author's

The studies cited were concerned with

doctoral dissertation submitted to the Graduate

subjects'

attitudes, sex, and social class in

College of the University of Illinois, Urbana,

Illinois. The author is indebted to Norman E. relation to positive reinforcement only. In

Gronlund for the valuable assistance he provided this investigation these variables were exwith this study.

amined in relation to both positive and nega* Requests for reprints should be sent to Dewitt

C. Davison, College of Education, University of tive reinforcement.

Toledo, Toledo, Ohio 43606.

As noted, there is evidence of a positive

418

PERCEIVED REWARD VALUE OF TEACHER REINFORCEMENT

relationship between the individual's overt

responsiveness to positive reinforcement and

his attitude toward the dispenser of the reinforcement. However, the dynamics of this

relationship have been given scarce attention

in the literature. One of the ways it may be

conceptualized is in terms of Newcomb's

(1953) balance theory. His basic paradigm

involves the co-orientation of two individuals

(A and B) with respect to each other, and a

third concept (X) which may be any person,

object, event, or idea. The attitude of Person

A toward X is conjointly related to A's

attitude toward B and his perception of B's

attitude toward X. An individual tends to

agree with those toward whom he holds a

positive attitude and to disagree with those

toward whom he holds a negative attitude.

With reference to the problem described, if

the student has a positive attitude toward

the teacher, he tends to agree with the

spirit that he perceives is being held by the

teacher in offering the reinforcement. On the

contrary, if he has a negative attitude toward

the teacher, he is inclined to reject, to some

extent, the intent of the reinforcement, since

his unqualified acceptance of it would imply

agreement with someone he dislikes. It

should be noted that the terms "agree" and

"disagree," as applied in the context of this

study, do not denote opposite states, but

are used in a sense relative to each other,

and represent differences in degrees rather

than differences in kind. Thus, given two

attitudes by students toward teachers, one

positive and one negative, it was hypothesized that they would perceive the positive

reinforcement provided by liked teachers

as being more rewarding than that provided

by disliked teachers. Correspondingly, they

should perceive the negative reinforcement

provided by liked teachers as being more

aversiveand hence its removal as more

rewardingthan that provided by disliked

teachers.

METHOD

Subjects

The subjects for the study were 118 male and

138 female eighth-grade students from three

communities in Illinois. The communities were

predominately white and all had populations of

varying economic backgrounds.

419

Procedure

A 20-item questionnaire consisting of typical

classroom reinforcing behaviors of teachers was

developed prior to the study. Items for the questionnaire were provided by 77 eighth-grade students who were not a part of the sample for the

main study. The students were given a mimeographed paragraph describing common classroom

episodes which illustrated student-behaviorteacher-reinforcement sequences. The examples

included instances of both positive and negative

reinforcement and the associated student behaviors. The students were then asked to provide

as many similar episodes as they could think of

that they had witnessed. The teacher-reinforcing

behaviors chosen for items in the questionnaire

were those listed most often by respondents. A

complete description of the questionnaire and its

development is reported elsewhere (Davison,

1967). Twelve of the questionnaire items represented positive reinforcers and 8 represented

negative reinforcers. Subjects responded to the

questionnaire twice, once in reference to a "Liked"

teacher providing the reinforcement and once in

reference to a "Disliked" teacher providing the

reinforcement. The two teacher-referent conditions under which the questionnaire was administered were separated by 1 week, the order

being reversed for half of the subjects. On each

occasion, before responding to the questionnaire,

each subject was asked to select the teacher he

most (or least) preferred to have teach him, without identifying the teacher by name, and indicate

his attitude toward the teacher on a 5-point,

descriptive scale. The options on the scale ranged

from "I like him (or her) very much" to, "I dislike him (or her) very much." The results from this

scale were used only as a basis for confirming the

subject's attitude toward the teacher chosen. To

respond to the questionnaire items, subjects chose

from among five statements the one most indicative of their feelings about the reinforcing

behaviors in relation to one of the teacher referents. Following is an item taken from the questionnaire :

Suppose you were in this teacher's class and

he (or she) was busy doing something in the

hall, and your classmates became loud and

you tried to quiet them. If this teacher saw

you after class and praised you for what you

did, how would you feel?"

A. I would feel very good if this teacher did

this.

B. I would feel good if this teacher did this.

C. I would feel neither good nor bad if this

teacher did this.

D. I would feel bad if this teacher did this.

E. I would feel very bad if this teacher did

this.

Upon completion of the questionnaire, the

subjects were asked to provide certain personal

data, including their sex, age, and parents' occupations and educational backgrounds. The

420

DEWITT C. DAVISON

latter information was needed to obtain an index

of each subject's social-class position.

RESULTS

Each subject had four scores, one for

positive reinforcement dispensed by the

"Liked" teacher, one for positive reinforcement dispensed by the "Disliked" teacher,

and two corresponding negative reinforcement scores. The responses to the questionnaire items were assigned to three categories,

based on whether a subject responded positively, neutrally, or negatively to the reinforcement. The positive category included

Options A and B (see sample questionnaire

item), the neutral category included Option

C, and the negative category included Options D and E. In scoring the positive reinforcement items, responses in the positive

category were assigned three points, those

in the neutral category, two points, and those

in the negative category, one point. The

point values were assigned in the reverse

order for the negative reinforcement items.

There were 12 items in the scale representing positive reinforcers. Nine of the 12 items

consisted of social reinforcers and the remaining 3 consisted of material reinforcers.

The results on these three items were not

included in this portion of the analysis.

Therefore, for the items measuring positive

reinforcement, scale values may have ranged

from 9 to 27 points. Scale values for the eight

negative reinforcement items may have

ranged from 8 to 24 points.

The subjects were classified into three

social-class groupings, based on Hollingshead's (1965) Two Factor Index of Social

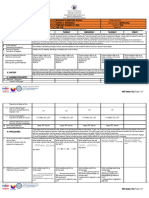

Position. Table 1 contains a summary of students by sex and social-class membership.

TABLE 1

NUMBER OF SUBJECTS WITHIN EACH SEX AND

SOCIAL CLASS GROUP

Social class

Boys

Girls

Both sexes

All groups

Lower

Middle

Upper

52

60

47

60

19

18

118

138

112

107

37

256

TABLE 2

MEANS OF POSITIVE REINFORCEMENT SCORES

Boys

Girls

Social class

Liked

teachers

Disliked

teachers

Liked

teachers

Disliked

teachers

Upper

Middle

Lower

24.84

23.21

24.77

23.81

22.94

25.96

25.50

25.18

24.70

22.55

23.57

24.00

All groups

25.43

23.92

24.27

23.37

The means of positive reinforcement scores

for various groups are shown in Table 2.

An analysis of variance of the positive reinforcement scores indicated significant main

effects of attitude toward teacher (F =

41.93, df = 1/250, p < .001), sex of subject

(F = 5.28, df = 1/250, p < .05), and subjects' social class (F = 5.72, df = 2/250, p

< .01). As predicted, subjects responded

more favorably to positive reinforcement

offered by "Liked" teachers than by "Disliked" teachers. Boys responded more favorably to the positive reinforcement than did

girls. There was also a significant social-class

difference. Tests of the means with Duncan's

new multiple-range test (Kramer, 1956) revealed that middle-class subjects perceived

the positive reinforcement as being significantly more rewarding than the upper-class

subjects (p < .01). Lower-class subjects

were intermediate between the middle- and

upper-class subjects in how they regarded

the positive reinforcement, and did not differ

significantly from either of the other two

groups.

The means of various groups for negative

reinforcement scores are shown in Table 3.

An analysis of variance of the negative

reinforcement scores revealed a significant

main effect of attitude toward teacher (F =

26.79, df = 1/250, p < .001). There were no

significant main effects on the dependent

variable due to sex or social class. In summary, when negative reinforcement was provided by a "Liked" teacher, subjects regarded it with more aversion than when it

was provided by a "Disliked" teacher. These

findings were also in agreement with the

prediction. However, there were no signifi-

PERCEIVED REWARD VALUE OF TEACHER REINFORCEMENT

TABLE 3

MEANS OF NEGATIVE REINFORCEMENT SCORES

Boys

Social class

Girls

Liked

teachers

Disliked

teachers

Liked

teachers

Disliked

teachers

Upper

Middle

Lower

21.32

22.26

21.48

19.74

21.36

20.69

21.44

22.70

21.80

20.72

21.16

21.05

All groups

21.84

20.85

22.19

21.06

cant differences between sexes and social

classes in how they responded to the negative

reinforcement.

DISCUSSION

It is widely recognized that how individuals respond to events is determined in part

by their perceptions of the events. Given

this relationship, it may be inferred from this

study that the attitude of the student toward

the teacher significantly affects the extent

to which he is able to influence his behavior

through positive and negative reinforcement.

Negative attitudes toward the teacher from

students apparently have the effect of diminishing the reward value they assign to his

positive reinforcement. Moreover, the aversive quality of his negative reinforcement

is regarded by them as being less penalizing,

under such conditions. The basis of their

resistance to reinforcement under these circumstances may be explained in one way by

the tendency of individuals to avoid orientations to events which align them with the

apparent orientations of persons they reject.

To accept the reinforcement in the spirit that

it is offered would imply alignment with the

source, and, to some extent, endorsement

of that source.

The sex differences that were observed in

the students' reactions to the positive reinforcement should be viewed with caution.

Related findings have been obtained in other

investigations (McManis, 1965; Rosenhan &

Greenwald, 1965). But other studies have

shown results inconsistent with these findings

(Ferguson & Buss, 1960; Rowley & Stone,

1964; Stevenson, 1961; Stevenson et al.,

1963). However, these studies concentrated

421

on the subjects' overt responses to the reinforcement rather than their affective responses to it.

Although a significant difference was noted

between two of the social classes in how they

responded to the positive reinforcement,

these findings are also not clear. The relationship between social class and reaction

to reinforcement may not be a simple one.

An examination of the literature reveals two

opposing positions on this question. On the

one hand, there is the view that the lowerclass child is conditioned by his environment

to value the intangible rewards associated

with the classroom less highly than his middle- and upper-class contemporaries. This

argument draws heavily on the works of

Davis (1941), Douvan (1956), and Ericson

(1947). On the other hand, there is the argument that since the lower-class child comes

from a background in which he has often

been deprived of social support, he develops

a greater need for such and is therefore more

responsive to it when it is offered. However,

the middle- and upper-class child's needs

for social support are satiated, by virtue of

their backgrounds. The principal exponent

of this notion is Rosenhan (1966). Considering both arguments, it is possible that the

outcome in this investigation relative to the

influence of social class on reaction to positive reinforcement was in part a reflection

of these two conflicting tendencies.

REFERENCES

DAVIS, A. American status system and the socialization of the child. American Sociological

Review, 1941, 5, 345-354.

DAVISON, D. C. Some demographic and attitudinal

concomitants of the perceived reward value of

classroom reinforcement: An application of

Newcomb's balance theory. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois) Ann Arbor, Mich.:

University Microfilms, 1967, No. 68-1739.

DOUVAN, E. Social status and success strivings.

Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology,

1956, 52, 219-223.

EBICSON, M. C. Social status and child rearing

practices. In T. M. Newcomb & E. L. Hartley

(Eds.), Readings in social psychology. New York:

Holt, 1947.

FERGUSON, D. C., & Buss, A. H. Operant conditioning of hostile verbs in relation to experimenter and subject characteristics. Journal of

Consulting Psychology, 1960, 24, 324-327.

422

DEWITT C. DAVISON

HOLLINGSHEAD, A. B. Two-factor index of social

position. New Haven: Yale Station, 1965.

KRAMEB, C. Y. Extension of multiple range tests

to group means with unequal numbers of replications. Biometrics, 1956, 12, 307-310.

McCoy, N., & ZIGLEB, E. Social reinforcer effectiveness as a function of the relationship

between child and adult. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 1965, 1, 604-612.

McGBADB, B. J. Variation in the effectiveness of

verbal reinforcers with age and social class.

Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Yale University, 1965.

McMANis, D. L. Pursuit-rotor performance of

normal and retarded children in four verbal

incentive conditions. Child Development, 1965,

36, 667-683.

MEYEB, W. J., SWANSON, B., & KAXJCHACK, N.

Studies of verbal conditioning: Effects of age,

sex, intelligence and "reinforcing stimuli." Child

Development, 1964, 35, 499-510.

NEWCOMB, T. M. An approach to the study of

communicative acts. Psychological Review,

1953, 60, 393-404.

ROSENHAN, D. L. Effects of social class and race

on responsiveness to approval and disapproval.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

1966, 4, 253-259.

ROSENHAN, D. L., & GREENWALD, J. A. The effects

of age, sex, and socioeoonomio class on responsiveness to two classes of verbal reinforcement.

Journal of Personality, 1965, 33, 108-121.

ROWLEY, V. N., & STONE, F. B. Changes in children's verbal behavior as a function of social

approval, experimenter differences, and child

personality. Child Development, 1964, 35, 669676.

SAPOLSKY, A. Effect of interpersonal relationships

upon verbal conditioning. Journal of Abnormal

and Social Psychology, 1960, 60, 241-246.

SIMKINS, L. Effects of examiner attitudes and type

of reinforcement on the conditioning of hostile

verbs. Journal of Personality, 1961, 24, 380-395.

STEVENSON, H. W. Social reinforcement with

children as a function of CA, sex of E, and sex

of S. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology,

1961, 62, 147-154.

STEVENSON, H. W., KEEN, R., & KNIGHTS, R. M.

Parents and strangers as reinforcing agents for

children's performance. Journal of Abnormal

and Social Psychology, 1963, 67, 183-186.

TERBELL, G., DURKIN, K., & WIESLEY, M. Social

class and the nature of the incentive in discrimination learning. Journal of Abnormal and

Social Psychology, 1959, 59, 270-272.

ZIGLEB, E., & DELABRY, J. Concept-switching in

middle-class, lower-class, and retarded children.

Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology,

1962, 54, 267-273.

ZIGLEB, E., & KANZER, P. The effectiveness of two

classes of verbal reinforcers on the performance

of middle and lower-class children. Journal of

Personality, 1962, 30, 157-163.

(Received March 30,1971)

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Yastrebova-Vladykina Uchebnik 2 Kursa PDFДокумент366 страницYastrebova-Vladykina Uchebnik 2 Kursa PDFKarinaОценок пока нет

- EthicsДокумент15 страницEthicsjp gutierrez100% (3)

- Critical Thinking: Critical Thinking... The Awakening of The Intellect To The Study of ItselfДокумент11 страницCritical Thinking: Critical Thinking... The Awakening of The Intellect To The Study of ItselfLeonard Ruiz100% (1)

- Content Analysis ReportДокумент4 страницыContent Analysis Reportjanice daefОценок пока нет

- Sample Module OutlineДокумент3 страницыSample Module OutlineReiОценок пока нет

- IR - Set 1Документ5 страницIR - Set 1Bhavy SinghОценок пока нет

- HW1 (10 Books) PDFДокумент5 страницHW1 (10 Books) PDFJohn Cedric SatojetoОценок пока нет

- Tense Exercise With Answers: Q1. Choose The Correct Verb From Those in BracketsДокумент7 страницTense Exercise With Answers: Q1. Choose The Correct Verb From Those in BracketsMike TysonОценок пока нет

- Mental Toughness Research PaperДокумент6 страницMental Toughness Research PaperrajdecoratorsОценок пока нет

- Key Performance-IndicatorsДокумент31 страницаKey Performance-IndicatorsSHARRY JHOY TAMPOSОценок пока нет

- Chute - Module 4 - Lesson PlanДокумент4 страницыChute - Module 4 - Lesson Planapi-601262005Оценок пока нет

- History & Psychology Assignment FullДокумент13 страницHistory & Psychology Assignment FullKunavathy Raman100% (1)

- Romeo and Juliet Lesson Plan 6 Sar PDFДокумент2 страницыRomeo and Juliet Lesson Plan 6 Sar PDFapi-283943860Оценок пока нет

- The Influence of Learning Style On English Learning Achievement Among Undergraduates in Mainland ChinaДокумент16 страницThe Influence of Learning Style On English Learning Achievement Among Undergraduates in Mainland ChinaThu VânnОценок пока нет

- Brown's Competency Model Assessment DictionaryДокумент1 страницаBrown's Competency Model Assessment DictionarytarunchatОценок пока нет

- The Application of Testing ACROSS CULTURESДокумент3 страницыThe Application of Testing ACROSS CULTURESBrighton MarizaОценок пока нет

- Trends in Organizational Development by Jonathan MozenterДокумент11 страницTrends in Organizational Development by Jonathan MozenterJonathan Mozenter88% (8)

- Notes On A Polyglot: Kato LombДокумент4 страницыNotes On A Polyglot: Kato Lombelbrujo135Оценок пока нет

- Bret Moore Fundamentals 2Документ2 страницыBret Moore Fundamentals 2THERESE MARIE B ABURQUEZОценок пока нет

- Bach QueationnaireДокумент31 страницаBach Queationnairekanpsn100% (1)

- AECS Lab ManualДокумент42 страницыAECS Lab ManualPhaneendra JalaparthiОценок пока нет

- Academic Skills and Studying With ConfidenceДокумент8 страницAcademic Skills and Studying With ConfidenceMaurine TuitoekОценок пока нет

- Writing and LearningДокумент80 страницWriting and Learningaristokle100% (1)

- The Seven Standards of Textuality Lecture 3Документ2 страницыThe Seven Standards of Textuality Lecture 3Ynne Noury33% (3)

- Chapter IДокумент5 страницChapter ILouid Rama MutiaОценок пока нет

- ProfEd - Articles in EducationДокумент37 страницProfEd - Articles in EducationAvan LaurelОценок пока нет

- Philo - Mod1 Q1 Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person v3Документ27 страницPhilo - Mod1 Q1 Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human Person v3Dia Dem LabadlabadОценок пока нет

- DLL Arts Q3 W5Документ7 страницDLL Arts Q3 W5Cherry Cervantes HernandezОценок пока нет

- Wordsworth Theory of PoetryДокумент4 страницыWordsworth Theory of Poetryhauwa adamОценок пока нет

- CHAPTER 10 Using ObservationДокумент4 страницыCHAPTER 10 Using ObservationAllenОценок пока нет