Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Aly Hartsough Mag

Загружено:

api-305898745Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Aly Hartsough Mag

Загружено:

api-305898745Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

In Fields of GOLD

By Jason Overdorf | NEWSWEEK

he furnace Australia sailed into Chennai last month carrying a load of wheat

and, some warned, ill tidings. Indias

first wheat imports in six years marked

a reversal in the march toward food independence that the country began in the 1970s. To

M. S. Swaminathan, one of the agronomists

credited with sparking the so-called Green Revolution, the return of grain imports should be

seen as a wake-up call for a country that has in

recent years taken its ability to feed its people for

granted.

Though Indias government officially dismissed

the return of grain imports as a passing event,

Swaminathan and other experts saw it as the

latest sign of a long-term decline. The growth

rate of grain production has fallen from 1.5

percent before 1995 to 1 percent today, due to a

combination of bad management, unpredictable

weather and a growing water shortage. Meanwhile, the growth rate for all crops has fallen to

1.25 percent a year, the lowest level since India

gained independence in 1947, says Ramesh

Chand, acting director of Indias National Centre

for Agricultural Economics and Policy Research.

Thats too slow to keep pace with a population

now growing, according to United Nations

estimates, at a rate of 1.5 percent a year. Chand

says the threat to Indias food independence is

manageable, if the government makes the right

moves.

These are sobering indicators for the Green

Revolution, which was originally inspired by

grave threats to the food supply in India. After

back-to-back droughts put the country in danger of massive starvation in 1966, a U.S. presidential-advisory commission called for an ef-

NEWSWEEK

61

fort unprecedented in human history to raise farm

output around the world. And so it did, as scientists

produced new strains of rice and wheat that boosted

yields by a factor of five, with the help of heavy irrigation and applications of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. In India, an initially well-executed campaign

raised grain output from 82 million metric tons in

1960 to 176 million tons in 1990 and cut imports to

zero by 2000. That is, until the trend reversed last

month.

Now production gains are slowing as the water supply dwindles, overzealous use of fertilizer and pesticides taints the soil and excessive irrigation waterlogs

the land along canals in the showpiece states of Indias Green Revolution, like the Punjab and Haryana.

Because irrigated land is two and ahalf times more

productive than rain-fed land, many of the gains of

the Green Revolution were produced by an increase

in the area under irrigation. But as Indias population

and economy grow, water supplies are shrinking. Already, the World Bankestimates, India meets most

of its irrigation and household demand by tapping

groundwater--a practice that is no longer sustainable.

Similar threats haunt China and other developing

nations that were big beneficiaries of the Green Revolution. China has responded by relaxing its commitment to being completely self-sufficient in the

production of food--encouraging farmers to grow

more lucrative fruits and vegetables, while importing

wheat and soybeans. To free-trade advocates, this approach makes sense--why obsess over food independence in an increasingly global free market, if others

grow wheat more efficiently than you do? Focus on

the goods, agricultural or

not, that you grow most efficiently.

Indeed, when Indian Prime

Minister Manmohan Singh

called in January for a second Green Revolution, his

concern focused on raising

farm incomes, not securing

the food supply. He called

for a fresh emphasis on

fruits, vegetables and new

plant varieties that would

command higher prices in

export markets. He also

encouraged measures to

NEWSWEEK

harvest rainwater more efficiently, improve the soil

and spread the benefits of agricultural technology,

including genetically modified seeds.

But the basic position of the Singh government is

that India normally produces more grain than it consumes, and soon will again. As for the recent return

to imports, officials dismissed it as a procurement

snafu: this year, for the first time, India allowed private buyers, including multinationals, to buy wheat

directly from farmers. That helped push up prices,

and the government responded by refusing to match

the prices offered by private buyers. It wound up buying less wheat than usual for the federal program that

provides subsidized grain to 150 million poor Indians.

When supplies fell short, the government had to turn

to imports--temporarily, officials insist.

Critics argue that Singh and his government are missing the big picture. Farm-policy analyst Devinder

Sharma complains that the people who govern this

country believe technology is the answer to every

problem, and are pushing a second revolution without examining why the first has collapsed. Chand

says the key going forward is to target backward states

like Bihar and Madhya Pradesh, which have done little

to modernize their farms, and thus have huge potential to reverse the slowdown in output.

One reason for these problems is that over the past

decade India, as part of its effort to reduce the state

role in the economy, has cut back significantly on investment in farms. Public-sector investment fell from

just over 2 percent of agricultural output in 1991 to

less than 1.5 percent in 2001. That slashed funds for

upgrading Green Revolution technologies and for the

extension programs that teach farmers how to make it

all work.

By the late 1980s, when

the early gains made in

rice and wheat had slowed,

India attempted to extend

its success to pulses (peas

and beans) and oilseeds.

Though it did manage to

produce high-yield seeds,

the program failed to supply

enough of these seeds to

farmers, and poor oversight

allowed corrupt traders to

pass off ordinary seeds as

high-yield hybrids, says

Delhi University agricul63

Вам также может понравиться

- Concersion System of Agriculture FarmingДокумент9 страницConcersion System of Agriculture FarmingAshutosh GuptaОценок пока нет

- Lit Survey Report - CH19125 0 CH19127Документ15 страницLit Survey Report - CH19125 0 CH19127DISHANK RANAОценок пока нет

- Role of Technology in Economic DevelopmentДокумент14 страницRole of Technology in Economic DevelopmentArnavОценок пока нет

- Green RevolutionДокумент13 страницGreen RevolutiondebasishroutОценок пока нет

- A PAPER ON Green RevolutionДокумент14 страницA PAPER ON Green RevolutionSrabon Shahriar RafinОценок пока нет

- Indian Agriculture SectorДокумент5 страницIndian Agriculture SectorNikhil JainОценок пока нет

- Group 2 - Agricultural Sector ReportДокумент24 страницыGroup 2 - Agricultural Sector ReportNanak ChhabraОценок пока нет

- Green Revolution 1Документ6 страницGreen Revolution 1Deepak SoniОценок пока нет

- Green RevolutionДокумент5 страницGreen RevolutionAlex ChettyОценок пока нет

- Green Revolution SaДокумент14 страницGreen Revolution SaSanskar AgarwalОценок пока нет

- Rupal Gupta DissertationДокумент28 страницRupal Gupta Dissertationrupal_delОценок пока нет

- Green RevolutionДокумент5 страницGreen RevolutionPrathamesh RandiveОценок пока нет

- Kendriya Vidyalaya Thiruvannamalai: Sumitted by Sangavi Sumitted To Kannan SirДокумент10 страницKendriya Vidyalaya Thiruvannamalai: Sumitted by Sangavi Sumitted To Kannan SirParameswari 1378Оценок пока нет

- Veermata Jijabbai Technological Institute Green RevolutionДокумент8 страницVeermata Jijabbai Technological Institute Green RevolutionRaj VishwakarmaОценок пока нет

- Green Revolution in India: A Case StudyДокумент5 страницGreen Revolution in India: A Case StudyKhanak ChauhanОценок пока нет

- IntroductionДокумент12 страницIntroductionbhargavi mishraОценок пока нет

- Importance of Green Revolution in India Economic DevelopmentДокумент4 страницыImportance of Green Revolution in India Economic DevelopmentSwagBeast SKJJОценок пока нет

- Green Revolution OR Third Agricultural RevolutionДокумент15 страницGreen Revolution OR Third Agricultural RevolutionSanskar AgarwalОценок пока нет

- Sustainable Development: Assignment - 1Документ8 страницSustainable Development: Assignment - 1Smriti SОценок пока нет

- Ass 1 PDFДокумент8 страницAss 1 PDFSmriti SОценок пока нет

- The Revolutions That Made A Mark in IndiaДокумент4 страницыThe Revolutions That Made A Mark in IndiaFred ThompsonОценок пока нет

- Essay On Green Revolution in IndiaДокумент10 страницEssay On Green Revolution in Indiaprasanta mallickОценок пока нет

- Green Revolution in IndiaДокумент5 страницGreen Revolution in Indiaanurag_gpuraОценок пока нет

- Importance of Agriculture in Modern IndiaДокумент3 страницыImportance of Agriculture in Modern IndiaVajith RaghmanОценок пока нет

- Assignment Green RevolutionДокумент11 страницAssignment Green RevolutionDark Web LeakedОценок пока нет

- Benefits of The Green RevolutionДокумент3 страницыBenefits of The Green RevolutionAroob YaseenОценок пока нет

- DSB Campus Kumaun University: NainitalДокумент20 страницDSB Campus Kumaun University: NainitalAtul RaghuwanshiОценок пока нет

- All About Green RevolutionДокумент5 страницAll About Green RevolutionMansi JadhavОценок пока нет

- DFI Volume 1Документ131 страницаDFI Volume 1shruthinОценок пока нет

- Green RevolutionДокумент11 страницGreen Revolutionyuvrajmishra041Оценок пока нет

- Agriculture Policy in India - IEP - 2021Документ17 страницAgriculture Policy in India - IEP - 2021JAYANT ARORAОценок пока нет

- Coming of First Green RevolutionДокумент37 страницComing of First Green RevolutionSanjeevОценок пока нет

- GreenrevolutionДокумент11 страницGreenrevolutionEwout KesselsОценок пока нет

- Green RevolutionДокумент11 страницGreen RevolutionAnudeep KulkarniОценок пока нет

- Agriculture in IndiaДокумент10 страницAgriculture in IndiaJasbir SinghОценок пока нет

- Transforming Agriculture: The Green Revolution in AsiaДокумент8 страницTransforming Agriculture: The Green Revolution in AsiaRajesh VernekarОценок пока нет

- Green Revolution: It's Acheivements and FailuresДокумент24 страницыGreen Revolution: It's Acheivements and FailuresSingh HarmanОценок пока нет

- A Report On Agriculture Industry in India: Prof. Indrajeet Kole Prof. Prajakta GokhaleДокумент36 страницA Report On Agriculture Industry in India: Prof. Indrajeet Kole Prof. Prajakta GokhaleRajesh Swain100% (1)

- The Green Revolution: Presented by Harshit Chordia (39) Chirag JajooДокумент20 страницThe Green Revolution: Presented by Harshit Chordia (39) Chirag JajooshonimoniОценок пока нет

- Agricultureinindianeconomy 130911050909 Phpapp02Документ32 страницыAgricultureinindianeconomy 130911050909 Phpapp02chthakorОценок пока нет

- EVS NAMAN KANSAL BBA Assignment-1Документ11 страницEVS NAMAN KANSAL BBA Assignment-1Naman KansalОценок пока нет

- Project Report On The Revival of Indian AgricultureДокумент79 страницProject Report On The Revival of Indian Agricultureabhineet kumar singh100% (3)

- Comparison of Agricultural CountryДокумент6 страницComparison of Agricultural CountryhannanahmadОценок пока нет

- Greer EvolutionДокумент32 страницыGreer EvolutionSAIRIPALLY SAI SURYA (B16CS029)Оценок пока нет

- DFI Vol-12AДокумент213 страницDFI Vol-12ADanish NehalОценок пока нет

- 70 Years Farmers ' JourneyДокумент20 страниц70 Years Farmers ' JourneySharanya ShrivastavaОценок пока нет

- Green Revolution (Final)Документ6 страницGreen Revolution (Final)Adarsh SinghОценок пока нет

- IRRI Annual Report 1999-2000Документ72 страницыIRRI Annual Report 1999-2000CPS_IRRIОценок пока нет

- Types of Agricultural PoliciesДокумент27 страницTypes of Agricultural PoliciesDigesh Shah88% (8)

- Farming System in India and Its TypesДокумент6 страницFarming System in India and Its TypesSHALINI A SОценок пока нет

- Green RevolutionДокумент20 страницGreen RevolutionDarasinghjat50% (2)

- Economic Reforms & Indian Agriculture, 4th SemДокумент3 страницыEconomic Reforms & Indian Agriculture, 4th SemGayatri Ramesh SutarОценок пока нет

- Agriculture in IndiaДокумент21 страницаAgriculture in IndiaSDPRABUОценок пока нет

- Rural Marketing RevolutionsДокумент4 страницыRural Marketing RevolutionsJenson DonОценок пока нет

- 1) Role of Agriculture in IndiaДокумент10 страниц1) Role of Agriculture in IndiagulhasnaОценок пока нет

- Agriculture Under The Five Year Plans AnДокумент13 страницAgriculture Under The Five Year Plans Anvivek tripathiОценок пока нет

- Green Revolution in IndiaДокумент2 страницыGreen Revolution in IndiaNitinОценок пока нет

- Agriculture in India: Contemporary Challenges: in the Context of Doubling Farmer’s IncomeОт EverandAgriculture in India: Contemporary Challenges: in the Context of Doubling Farmer’s IncomeОценок пока нет

- Agriculture Interview Questions and Answers: The Complete Agricultural HandbookОт EverandAgriculture Interview Questions and Answers: The Complete Agricultural HandbookОценок пока нет

- BBQ SauceДокумент1 страницаBBQ Sauceapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Aly Hartsough ResumeДокумент1 страницаAly Hartsough Resumeapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- West View BrochureДокумент2 страницыWest View Brochureapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Stocking StuffersДокумент1 страницаStocking Stuffersapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Stocking StuffersДокумент1 страницаStocking Stuffersapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Northside MiddleДокумент2 страницыNorthside Middleapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- East WashingtonДокумент2 страницыEast Washingtonapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Grissom BrochureДокумент2 страницыGrissom Brochureapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Mitchell BrochureДокумент2 страницыMitchell Brochureapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Poster 2 EditДокумент1 страницаPoster 2 Editapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Southside MiddleДокумент2 страницыSouthside Middleapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Longfellow BrochureДокумент2 страницыLongfellow Brochureapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- GolfbioДокумент3 страницыGolfbioapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Central HsДокумент2 страницыCentral Hsapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Business CardДокумент1 страницаBusiness Cardapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Newsletter 1Документ2 страницыNewsletter 1api-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Synchro BrocherДокумент2 страницыSynchro Brocherapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Newsletter 2Документ2 страницыNewsletter 2api-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Red Cross Ad2Документ1 страницаRed Cross Ad2api-305898745Оценок пока нет

- PosterДокумент1 страницаPosterapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- LetterheadДокумент1 страницаLetterheadapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Amish CountryДокумент1 страницаAmish Countryapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Horse PowerДокумент1 страницаHorse Powerapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Turkey Run1Документ1 страницаTurkey Run1api-305898745Оценок пока нет

- ElkhardДокумент1 страницаElkhardapi-305898745Оценок пока нет

- Sorghum Root and Stalk RotsДокумент288 страницSorghum Root and Stalk RotsFindi DiansariОценок пока нет

- Tenant Emancipation LawДокумент30 страницTenant Emancipation LawJaybel Ng BotolanОценок пока нет

- Coco Cost of Production1Документ3 страницыCoco Cost of Production1Cristobal Macapala Jr.Оценок пока нет

- Media ListAgriculture Commodities Engagement GridДокумент17 страницMedia ListAgriculture Commodities Engagement GridSudeep SenguptaОценок пока нет

- Praveen English ProjectДокумент11 страницPraveen English Projectv.a.praveen247Оценок пока нет

- Pinaka Bagong Thesis2.0.00000Документ21 страницаPinaka Bagong Thesis2.0.00000Rebecca Pizarra GarciaОценок пока нет

- (Week 4-5) Agricultural ExtensionДокумент19 страниц(Week 4-5) Agricultural ExtensionIts Me Kyla RuizОценок пока нет

- Herdsmen Farmers Conflict and Food Security in Nigeria A Case Study of Lau LgaДокумент58 страницHerdsmen Farmers Conflict and Food Security in Nigeria A Case Study of Lau LgaDaniel Obasi100% (3)

- IRRIGATION Notes PDFДокумент77 страницIRRIGATION Notes PDFniteshОценок пока нет

- Harvesting HoneyДокумент27 страницHarvesting Honeyapi-262572717Оценок пока нет

- Rejuvenating Old Apple TreesДокумент2 страницыRejuvenating Old Apple TreesConnecticut Wildlife Publication LibraryОценок пока нет

- Atlas Fertilizer vs. SecДокумент2 страницыAtlas Fertilizer vs. SecAnsis Villalon PornillosОценок пока нет

- AGRO-INDUSTRy DEvElOpmENTДокумент2 страницыAGRO-INDUSTRy DEvElOpmENTAlex Lopez CordobaОценок пока нет

- Steuben County Real Estate Guide - July 2011Документ80 страницSteuben County Real Estate Guide - July 2011KPC Media Group, Inc.Оценок пока нет

- Region 4b RomblonДокумент52 страницыRegion 4b RomblonRonaly Licay Seguancia100% (1)

- The Objective of The Project Is To Study Market Potential of Parag Milk and To Know TheconsumerДокумент13 страницThe Objective of The Project Is To Study Market Potential of Parag Milk and To Know TheconsumerNeeraj SinghОценок пока нет

- What Is The World BankДокумент4 страницыWhat Is The World BankPrincess KanchanОценок пока нет

- Dehydration FinalДокумент14 страницDehydration FinalStephen Moore100% (1)

- About Dalmia CementДокумент26 страницAbout Dalmia CementSathish Babu100% (3)

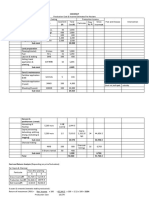

- Machinery and Equipment Cost Worksheet Calculates Breakeven Acreages and Custom RatesДокумент11 страницMachinery and Equipment Cost Worksheet Calculates Breakeven Acreages and Custom RatesBerat HasolliОценок пока нет

- Assignment CFN 2Документ9 страницAssignment CFN 2Shashi Bhushan Sonbhadra67% (3)

- Why Is The Aral Sea ShrinkingДокумент6 страницWhy Is The Aral Sea ShrinkingOmar BermudezОценок пока нет

- DDEX3-1 Harried in HillsfarДокумент45 страницDDEX3-1 Harried in Hillsfarandy jenks100% (1)

- Weasler FlipbooxДокумент134 страницыWeasler FlipbooxJoe UnanderОценок пока нет

- Drying Part 1Документ166 страницDrying Part 1WalterОценок пока нет

- Causes of Biodiversity Loss A Human Ecological Analysis by Emmanuel Boon and HensДокумент16 страницCauses of Biodiversity Loss A Human Ecological Analysis by Emmanuel Boon and HensAshishKajlaОценок пока нет

- P 03 Glenn McGourty - Bio DynamicДокумент6 страницP 03 Glenn McGourty - Bio DynamicDebatdevi IncaviОценок пока нет

- 1860 Indian Census of Gay Head (Aquinnah), Dukes Co., MassДокумент9 страниц1860 Indian Census of Gay Head (Aquinnah), Dukes Co., MassCandice LeeОценок пока нет

- Strategic Factor Analysis For Exporter of Robusta Coffee Bean From Lampung, South Sumatra, IndonesiaДокумент7 страницStrategic Factor Analysis For Exporter of Robusta Coffee Bean From Lampung, South Sumatra, IndonesiasfasffОценок пока нет

- Study of PomeloДокумент30 страницStudy of PomeloKyle Cabusbusan75% (4)