Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

1-s2 0-S1097276510000407-Main

Загружено:

api-238806436Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

1-s2 0-S1097276510000407-Main

Загружено:

api-238806436Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Molecular Cell

Forum

How to Build a Motivated Research Group

Uri Alon1,*

1Department of Molecular Cell Biology, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel

*Correspondence: urialon@weizmann.ac.il

DOI 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.011

Motivated group members experience a full sense of choice: of doing what one wants. Such behavior shows

high performance, is enjoyable, and enhances innovation. This essay describes principles of building a motivated research group.

Most students begin graduate school or

a postdoc full of passion for science.

They are given the resources to devote

themselves to solving fascinating puzzles.

Why is it, then, that in some groups

students thrive, cant wait to come to the

lab in the morning, cant stop thinking

about their projects, and feel a sense of

personal and intellectual growth, whereas

in the lab next door, students after two

years are depressed, unmotivated, and,

by the end, are loath to even look at their

own papers?

We all want to work with motivated

students and keep ourselves motivated.

But how? We are never taught about

motivation or about most other essential

topics related to the emotional and

subjective aspects of being a scientist. A

common implicit assumption is that motivation is the sole responsibility of the

student: either you have it or you dont.

This can lead researchers to blame group

members for their lack of motivation.

However, research in psychology has

begun to demystify motivation and can

offer useful concepts for scientists. The

goal is to provide people with the conditions that enhance their natural self-motivated behavior. Here, I discuss simple

principles that are useful for building

a highly motivated research group.

The psychologists Deci and Ryan have,

since the 1970s, studied conditions

that enable self-determined behavior:

behavior that is experienced with a full

sense of choice, of doing what one wants,

without coercion or compulsion. Such

behavior shows high performance, is

enjoyable, and enhances innovation. Of

many experiments, here is an illustrative

example: People are given interesting

mechanical puzzles to solve. Group A

is given a dollar for solving each puzzle; Group B is not. After 30 min, the

researchers tell the groups that the experiment is done. It was found that Group A

puts the puzzles down, whereas Group

B keeps playing with them on their own

time. The surprise was that money and

other rewards in these types of tasks

apparently act to reduce motivation.

What makes people motivated?

Deci and Ryan found three conditions

for self-determined behavior: competence, autonomy, and social connectedness. Ill now describe how these

concepts are useful in the context of

research groups.

Competence is a prerequisite for motivation. Peak performancecalled flow

in psychologyis achieved at intermediate difficulty of tasks: not too easy and

not impossible. To demonstrate how

advisers could go wrong, here is a mistake

I made with my first graduate student. For

his first project, I suggested that he rewire

a commercial fluorimeter to oscillate its

temperature control and see how bacterial growth is affected. This seemed

reasonable to me coming fully charged

from my postdoc, but for him was justifiably daunting, as a beginning student

who had never even grown bacteria in

a test tube. After a short while, I sensed

the drop in motivation.

We started over: first grow bacteria in

a test tube. Good. Now do a growth curve.

Good. Now do it again and estimate the

day-day error. Good. Easy steps allowed

positive reinforcement. As his confidence

increased, his motivation skyrocketed.

The best part is that going slowly allowed

us the time to find a different and much

more interesting project than the one I first

assigned. I have since been careful to

gradually build competence and confidence for new group members, with the

help of more experienced members,

clearly stating the purpose at each step.

In addition to competence, autonomy is

essential for motivation. Autonomy is the

sense that the project emanates from

the person and not from an external

source. Using threats or punishment

tends to decrease autonomy. One can

also decrease autonomy in more subtle

ways. One graduate student told me: I

have a question, but before I tell you,

please promise not to solve it immediately

by yourselfI want time to think about it.

I realized that as experienced scientists,

who see several steps ahead, we need

to be mindful of sometimes letting

students figure things out for themselves.

Autonomy is related to the amount of

structure (instructions from the mentor):

autonomy is optimal at intermediate

structure, between the extremes of micromanagement and neglect. The optimal

point is specific to each individual and

changes over time because experienced

group members need less structure. You

thus need to determine and adjust this

point together.

The third strand of motivation is social

connectedness: having someone in the

group care about you and your project.

The need for connectedness encompasses the striving to care for others, to

feel that others relate to you in mutually

supportive ways, and to feel a satisfying

involvement with the social world (and

the scientific world) more generally.

I make our weekly group meeting an

event that enhances social connectedness. The first half hour of the two hour

meeting is devoted to nonscience. This

at first may seem to eliminate one quarter

of the time for talking science, but in the

long term, gains from increased motivation more than make up for any losses. I

begin by asking who is not here today,

so that we feel a sense of responsibility

for each other, contacting people who

Molecular Cell 37, January 29, 2010 2010 Elsevier Inc. 151

Molecular Cell

Forum

are sick, etc. We then celebrate

general objectives of science:

lab rituals, such as birthdays.

Greek literature is not yet in O. If

We spend time freely discussing

you cannot find anything in O

the news, arts, etc. There is

that overlaps your talents and

a time for anyone to make

passions, perhaps it is time to

announcements to the group

leave science for something you

(new equipment, interesting

are passionate about.

papers, upcoming vacations).

Interaction between people is

And then a student gives a scienof course far more complex

tific talk, in which the group is

than can be captured with such

given a role: imaginary referees

simple concepts. Still, these

if the project is before publicaconcepts are useful to me as

tion, brainstormers if this is

diagnostics and guides. They

a preliminary talk about a future

sometimes are at odds and

project. I am mindful to explain

must be balanced, for example,

jargon to newcomers and to

in choosing a project for a new

appreciate members for effort in

student: competence considerthe face of tough problems and

ations may require finding

for helping each other. Over the

a group member who can help,

years, this has created a culture

causing overlap in projects,

of connectedness in the lab that

which can reduce autonomy.

Figure 1. The TOP Model

is one of my main joys.

Autonomy considerations sugGood projects are found in the intersection of ones talents and

Social connectedness is a

gest clear separation between

passions and the objectives/scientific interests of the group.

major motivating factor for

student projects. However, havmany scientists. Though there

ing a project that is too different

is a romantic notion that scientists are enhances self-determination. The goal is from all the others in the group can

solitary people, there are many people to choose a project that aligns with the decrease the sense of connectedness.

that think best in discussions and gain students unique set of skills and inter- There is no formula, but concepts can

great satisfaction from helping others. ests. It is a simple graphic called the help guide common sense. Open converAnd sometimes its even simpler than TOP model (Figure 1). Imagine three sations with colleagues who struggle with

that: a lot of lab work is dull, and having circles. The first is T, for talents. The similar decisions and with your own group

people to joke with and chat to can turn second is P, for passions, which inter- can help you adjust and enable your

a mundane day into a fantastic one. sects (but does not completely overlap) group and yourself to reach the full potenA colleague of mine said that she became with T. The homework for the student is tial of intrinsic motivation.

a scientist because she likes scientists to list his or her talents and passions,

and enjoys their way of looking at the even those that do not seem related to

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

world. Our connection to a community science. The final circle is O, objectives

and a culture provides us context and of the lab. The ideal project lies in the

These ideas were presented to me as gifts by

empathy during our struggles, celebra- intersection of the three. This provides teachers, students, and peers or are the fruits of

tions and acknowledgment during our constraints that, as in all creative work, learning from my own mistakes, and they are presuccesses.

can lead you to unexpected and original sented here again as a gift. I thank Amir Orian

and Jonathan Fox for training on building groups

If you are feeling unmotivated, these projects.

that nurture inclusiveness, innovation, creativity,

concepts might give clues on how to ask

Being in the intersection of talent, and humor, based on traditions of playback theatre

for help in competence, autonomy, or passion, and scientific objectives is moti- and psychodrama; Dan McAdams for his book The

Person; Angela DePace, Galit Lahav, Mike

social connectedness. If the situation is vating, because talent is related to Springer, and Ron Milo for discussions; and Allan

such that help cannot be found within competence, passion is an ingredient Drummond for inspiration and introducing me to

the group, it might help to nurture yourself of autonomy, and shared objectives the TOP model. See also the Forum on how to

by doing something that you love outside enhance social connectedness. I like to choose a scientific problem (Alon, 2009).

the lab.

use this especially when students consult

As we end this essay, Id like to with me about choosing a field for a post- REFERENCES

describe an approach to choosing a doc or starting a new lab. Here, we open

project with a student (or for myself) that a wide search, with O serving as the Alon, U. (2009). Mol. Cell 35, 726728.

152 Molecular Cell 37, January 29, 2010 2010 Elsevier Inc.

Вам также может понравиться

- Secret To CreativityДокумент6 страницSecret To Creativitymtwaits2506Оценок пока нет

- The Creative Advantage Lifecycle: Enhance your creativity throughout all stages of your lifeОт EverandThe Creative Advantage Lifecycle: Enhance your creativity throughout all stages of your lifeОценок пока нет

- Idea Lab AssginmentДокумент10 страницIdea Lab AssginmentAdvait NaikОценок пока нет

- Teaching and Research Statement: M. Henry H. StevensДокумент5 страницTeaching and Research Statement: M. Henry H. Stevensmekm09Оценок пока нет

- Unlock Your Creativity: A Guide To Boosting Your Imagination and Unleashing Your Inner Artist: Self Awareness, #10От EverandUnlock Your Creativity: A Guide To Boosting Your Imagination and Unleashing Your Inner Artist: Self Awareness, #10Оценок пока нет

- STS0 12 - Activity 3Документ2 страницыSTS0 12 - Activity 3JULIANA PATRICE PEREZОценок пока нет

- Teaching and Learning from Neuroeducation to Practice: We Are Nature Blended with the Environment. We Adapt and Rediscover Ourselves Together with Others, with More WisdomОт EverandTeaching and Learning from Neuroeducation to Practice: We Are Nature Blended with the Environment. We Adapt and Rediscover Ourselves Together with Others, with More WisdomОценок пока нет

- Good Copy of Capstone ProposalДокумент8 страницGood Copy of Capstone Proposalapi-636085078Оценок пока нет

- How to Study and Understand Anything: Discovering The Secrets of the Greatest Geniuses in HistoryОт EverandHow to Study and Understand Anything: Discovering The Secrets of the Greatest Geniuses in HistoryОценок пока нет

- Social Psychology Possible Thesis TopicsДокумент5 страницSocial Psychology Possible Thesis TopicsBuyEssaysCheapErie100% (2)

- Amigable (Entrep) 1Документ2 страницыAmigable (Entrep) 1Alexren AmigableОценок пока нет

- Thinking Dispositions ShariДокумент5 страницThinking Dispositions ShariGladys LimОценок пока нет

- How To Think Like Da VinciДокумент3 страницыHow To Think Like Da VincimvenОценок пока нет

- Final Paper 3000 1Документ19 страницFinal Paper 3000 1api-330206944Оценок пока нет

- Final Deliberation ReportДокумент4 страницыFinal Deliberation Reportapi-548278058Оценок пока нет

- An Article On The Foundation of The 4MAT ModelДокумент15 страницAn Article On The Foundation of The 4MAT ModelrhassankОценок пока нет

- Foundation of EducationДокумент10 страницFoundation of Educationmynel200873% (11)

- Turtles Farewell Talk For Grad Students 7May-Revised4June2010Документ6 страницTurtles Farewell Talk For Grad Students 7May-Revised4June2010ulluaolОценок пока нет

- Spring Reflection Artifact - Peer Educator Discussion PostsДокумент6 страницSpring Reflection Artifact - Peer Educator Discussion Postsapi-515727591Оценок пока нет

- Assignment 1: Allama Iqbal Open University, IslamabadДокумент8 страницAssignment 1: Allama Iqbal Open University, IslamabadQuran AcademyОценок пока нет

- Critical Thinking and Technology: Intrinsic MotivationsДокумент6 страницCritical Thinking and Technology: Intrinsic Motivationsluke74sОценок пока нет

- Peering Into LearningДокумент13 страницPeering Into Learningholtzermann17Оценок пока нет

- 8611 First AssignmentДокумент13 страниц8611 First AssignmentAmyna Rafy AwanОценок пока нет

- Linking Critical Theory and Critical ThinkingДокумент7 страницLinking Critical Theory and Critical ThinkingAanica VermaОценок пока нет

- Celebre, Trina Franchezca LДокумент12 страницCelebre, Trina Franchezca Ltrina celebreОценок пока нет

- PLC Chap 2 and 4 SummaryДокумент7 страницPLC Chap 2 and 4 SummarySunaila TufailОценок пока нет

- EDR Summury by Doctor MatlabaneДокумент8 страницEDR Summury by Doctor MatlabaneSihle.b MjwaraОценок пока нет

- Psychology of Learning - Student Emotional and Social DevelopmentДокумент5 страницPsychology of Learning - Student Emotional and Social DevelopmentRina MahusayОценок пока нет

- Example of Comparative EssayДокумент6 страницExample of Comparative Essaysoffmwwhd100% (2)

- Methods in Behavioural Research Canadian 2nd Edition Cozby Solutions ManualДокумент30 страницMethods in Behavioural Research Canadian 2nd Edition Cozby Solutions ManualDan Holland100% (30)

- Forum PostsДокумент7 страницForum Postsapi-375720436Оценок пока нет

- Full Download Methods in Behavioural Research Canadian 2nd Edition Cozby Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterДокумент36 страницFull Download Methods in Behavioural Research Canadian 2nd Edition Cozby Solutions Manual PDF Full Chaptercerebelkingcupje9q100% (21)

- Methods in Behavioural Research Canadian 2nd Edition Cozby Solutions ManualДокумент36 страницMethods in Behavioural Research Canadian 2nd Edition Cozby Solutions Manualbloteseagreen.csksmz100% (30)

- Strategies To Increase Critical Thinking Skills in StudentsДокумент19 страницStrategies To Increase Critical Thinking Skills in StudentsMajeedОценок пока нет

- Mod 1 Adolescent Brain Research PaperДокумент9 страницMod 1 Adolescent Brain Research Paperapi-548034328Оценок пока нет

- Social Psychology Research Papers PDFДокумент5 страницSocial Psychology Research Papers PDFlqinlccnd100% (1)

- Introduction To PsychologyДокумент783 страницыIntroduction To Psychologyhednin100% (1)

- Psychology AssignmentДокумент6 страницPsychology AssignmentHK 'sОценок пока нет

- Communication SkillsДокумент40 страницCommunication Skillsnajatul ubadatiОценок пока нет

- Communication in A Democracy 1Документ18 страницCommunication in A Democracy 1api-321545357Оценок пока нет

- 2099 - How To Choose Good ProblemДокумент3 страницы2099 - How To Choose Good ProblemMarcos RobertoОценок пока нет

- Cognitive Constructivism: Improving Student Communication SkillsДокумент4 страницыCognitive Constructivism: Improving Student Communication SkillsMaricel M. TaniongonОценок пока нет

- Statement of Teaching PhilosophyДокумент3 страницыStatement of Teaching PhilosophyMarsha PineОценок пока нет

- Thesis Topic For Social PsychologyДокумент4 страницыThesis Topic For Social Psychologyokxyghxff100% (2)

- What Is A Complex Attentional Structure and How Is It Related To Assimilation and Accommodation?Документ9 страницWhat Is A Complex Attentional Structure and How Is It Related To Assimilation and Accommodation?api-239129823Оценок пока нет

- Appraoch To Problem SolvingДокумент24 страницыAppraoch To Problem SolvingMohammad Shoaib DanishОценок пока нет

- Enhancing Studentsrsquo Creativity Through Creative Thinking TechniquesДокумент15 страницEnhancing Studentsrsquo Creativity Through Creative Thinking TechniquesFreddy Jr PerezОценок пока нет

- 620Wk1A1Learning TheoriesДокумент8 страниц620Wk1A1Learning TheoriesMichael DoctorSlime GarlickОценок пока нет

- Research Paper Topics in Social PsychologyДокумент7 страницResearch Paper Topics in Social Psychologyz1h1dalif0n3100% (1)

- Effects of Grade-Based SegregationДокумент5 страницEffects of Grade-Based SegregationCynthia SolomonОценок пока нет

- SummarizingДокумент2 страницыSummarizingapi-341337748Оценок пока нет

- Philosophy of Education and Its Relevance To SocietyДокумент3 страницыPhilosophy of Education and Its Relevance To Societymanuel radislaoОценок пока нет

- Thesis in Teaching Social SkillsДокумент7 страницThesis in Teaching Social Skillsqpftgehig100% (2)

- ACTIVITYДокумент4 страницыACTIVITYMelanie AmandoronОценок пока нет

- Observational Research Paper SampleДокумент7 страницObservational Research Paper Samplehyavngvnd100% (1)

- EDTECH 504 Reflections Module 2 ReflectionДокумент4 страницыEDTECH 504 Reflections Module 2 ReflectionJosh SimmonsОценок пока нет

- Design Thinking in EducationДокумент11 страницDesign Thinking in EducationGuyan GordonОценок пока нет

- Research Paper On Human BehaviorДокумент5 страницResearch Paper On Human Behavioregya6qzc100% (1)

- Developing Yourself and Others Job Aid: High-Payoff DevelopmentДокумент2 страницыDeveloping Yourself and Others Job Aid: High-Payoff DevelopmentDeon ConwayОценок пока нет

- Syllabus Advanced Cad Cam Spring 2013Документ6 страницSyllabus Advanced Cad Cam Spring 2013api-236166548Оценок пока нет

- Ethical Principles of ResearchДокумент15 страницEthical Principles of ResearchAstigart Bordios ArtiagaОценок пока нет

- Second 2023Документ85 страницSecond 2023hussainahmadОценок пока нет

- Baseline Assessment Worldbank PDFДокумент134 страницыBaseline Assessment Worldbank PDFYvi RozОценок пока нет

- (Paul Weindling) Victims and Survivors of Nazi Hum PDFДокумент337 страниц(Paul Weindling) Victims and Survivors of Nazi Hum PDFMarius Androne100% (2)

- 21st Century SkillsДокумент4 страницы21st Century SkillsKathrine MacapagalОценок пока нет

- Different Work Experiences of Grade 12 CSS Students During Work ImmersionДокумент29 страницDifferent Work Experiences of Grade 12 CSS Students During Work Immersionmenandro l salazar75% (12)

- Data Satakam: 'EdanyaДокумент285 страницData Satakam: 'EdanyaMalyatha Krishnan100% (3)

- Electronics PDFДокумент41 страницаElectronics PDFSumerОценок пока нет

- Siwestechnicalreport PDFДокумент68 страницSiwestechnicalreport PDFEmmanuel AndenyangОценок пока нет

- PGD Brochure 10th BatchДокумент13 страницPGD Brochure 10th BatchSaiful Islam PatwaryОценок пока нет

- Virtual Reality and EnvironmentsДокумент216 страницVirtual Reality and EnvironmentsJosé RamírezОценок пока нет

- Group3 Abm FinalДокумент43 страницыGroup3 Abm Finalkiethjustol070Оценок пока нет

- ADM (MIMOSA) Prof Ed 6Документ2 страницыADM (MIMOSA) Prof Ed 6Lester VillareteОценок пока нет

- Social GroupsДокумент5 страницSocial GroupsArchie LaborОценок пока нет

- 'Youth Ambassador Regular Newsletter' Issue 2 2008Документ24 страницы'Youth Ambassador Regular Newsletter' Issue 2 2008Doug MillenОценок пока нет

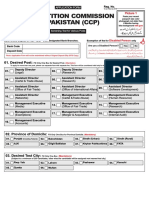

- Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) : S T NS T NДокумент4 страницыCompetition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) : S T NS T NMuhammad TuriОценок пока нет

- Junaid Mushtaq: Chemical EngineerДокумент2 страницыJunaid Mushtaq: Chemical EngineerEhitishamОценок пока нет

- Cambridge O Level: Chemistry 5070/12 October/November 2020Документ3 страницыCambridge O Level: Chemistry 5070/12 October/November 2020Islamabad ALMA SchoolОценок пока нет

- 0620 - w19 - Ms - 61 Paper 6 Nov 2019Документ6 страниц0620 - w19 - Ms - 61 Paper 6 Nov 2019Zion e-learningОценок пока нет

- Gymnastics WorkbookДокумент30 страницGymnastics Workbookapi-30759851467% (3)

- Understanding Children's DevelopmentДокумент48 страницUnderstanding Children's DevelopmentAnil Narain Matai100% (2)

- Advanced Methods For Complex Network AnalysisДокумент2 страницыAdvanced Methods For Complex Network AnalysisCS & ITОценок пока нет

- Doctoral Dissertation Title PageДокумент7 страницDoctoral Dissertation Title PageCheapestPaperWritingServiceSingapore100% (1)

- How To Become An ICAEW Chartered AccountantДокумент20 страницHow To Become An ICAEW Chartered AccountantEdarabia.com100% (1)

- Strategic Human Resource Management PDFДокумент251 страницаStrategic Human Resource Management PDFkoshyligo100% (2)

- 2024-2025-Admissions-Sep.-2024 GimpaДокумент3 страницы2024-2025-Admissions-Sep.-2024 GimpaIvan TaylorОценок пока нет

- Why Adults LearnДокумент49 страницWhy Adults LearnOussama MFZОценок пока нет

- People Development PoliciesДокумент22 страницыPeople Development PoliciesJoongОценок пока нет

- Summary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesОт EverandSummary: Atomic Habits by James Clear: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad OnesРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1635)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityОт EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (29)

- The Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismОт EverandThe Stoic Mindset: Living the Ten Principles of StoicismРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (10)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDОт EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (2)

- The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionОт EverandThe 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: The Infographics EditionРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2475)

- Summary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearОт EverandSummary of Atomic Habits: An Easy and Proven Way to Build Good Habits and Break Bad Ones by James ClearРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (560)

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)От EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Рейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (1)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionОт EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (404)

- Master Your Emotions: Develop Emotional Intelligence and Discover the Essential Rules of When and How to Control Your FeelingsОт EverandMaster Your Emotions: Develop Emotional Intelligence and Discover the Essential Rules of When and How to Control Your FeelingsРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (321)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsОт EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentОт EverandThe Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual EnlightenmentРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (4125)

- Becoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonОт EverandBecoming Supernatural: How Common People Are Doing The UncommonРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1481)

- Summary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneОт EverandSummary of The 48 Laws of Power: by Robert GreeneРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (233)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsОт EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsОценок пока нет

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedОт EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (81)

- No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelОт EverandNo Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems ModelРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (5)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeОт EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeРейтинг: 2 из 5 звезд2/5 (1)

- Eat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeОт EverandEat That Frog!: 21 Great Ways to Stop Procrastinating and Get More Done in Less TimeРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (3226)

- The 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageОт EverandThe 5 Second Rule: Transform your Life, Work, and Confidence with Everyday CourageРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (10)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisОт EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (30)

- The Science of Self Discipline: How Daily Self-Discipline, Everyday Habits and an Optimised Belief System will Help You Beat Procrastination + Why Discipline Equals True FreedomОт EverandThe Science of Self Discipline: How Daily Self-Discipline, Everyday Habits and an Optimised Belief System will Help You Beat Procrastination + Why Discipline Equals True FreedomРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (867)

- Codependent No More: How to Stop Controlling Others and Start Caring for YourselfОт EverandCodependent No More: How to Stop Controlling Others and Start Caring for YourselfРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (88)

- The Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeОт EverandThe Courage Habit: How to Accept Your Fears, Release the Past, and Live Your Courageous LifeРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (253)

- Indistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeОт EverandIndistractable: How to Control Your Attention and Choose Your LifeРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (5)