Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Jhumpa Lahiri-The Namesake Either (A) "One Hand, Five Homes, A Lifetime in A Fist."

Загружено:

Christopher HintonИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Jhumpa Lahiri-The Namesake Either (A) "One Hand, Five Homes, A Lifetime in A Fist."

Загружено:

Christopher HintonАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

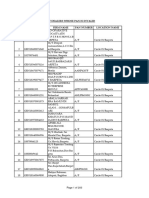

P3.

Poetry and Prose

Jhumpa Lahiri- The Namesake

Either (a) One hand, five homes, a lifetime in a fist."

How does Lahiri sum up Ashima's life in this one sentence just prior to her husband's death.

Or

(b) Discuss the following passage in detail, commenting on ways in which it presents Ashima's

family after her husband's demise.

The day after Christmas she left Pemberton Road, with the excuse to his mother and Sonia that a

last-minute interview had fallen into place at the MLA. But really the job was a ruse; she and Gogol

had decided that it was best for her to return to New York alone. By the time he arrived at the

apartment, her clothes were gone, and her make-up and her bathroom things. It was as if she were

away on another trip. But this time she didn't come back. She wanted nothing of the brief life they'd

had together; when she appeared one last time at his office a few months later, so that he could sign

the divorce papers, she told him she was moving back to Paris. And so, systematically, as he had

done for his dead father, he removed her possessions from the apartment, putting her books into

boxes on the sidewalk in the middle of the night for people to take, throwing out the rest. In the spring

he went to Venice alone for a week, the trip he'd planned for the two of them, saturating himself in its

ancient, melancholy beauty. He lost himself among the darkened narrow streets, crossing countless

tiny bridges, discovering deserted squares, where he sat with a Campari or a coffee, sketching the

facades of pink and green palaces and churches, unable ever to retrace his steps.

And then he returned to New York, to the apartment they'd inhabited together that was now all his. A

year later, the shock has worn off, but a sense of failure and shame persists, deep and abiding. There

are nights he still falls asleep on the sofa, without deliberation, waking up at three A.M. with the

television still on. It is as if a building he'd been responsible for designing has collapsed for all to see.

And yet he can't really blame her. They had both acted on the same impulse, that was their mistake.

They had both sought comfort in each other, and in their shared world, perhaps for the sake of

novelty, or out of the fear that that world was slowly dying. Still, he wonders how he's arrived at all

this: that he is thirty-two years old, and already married and divorced. His time with her seems like a

permanent part of him that no longer has any relevance, or currency. As if that time were a name he'd

ceased to use.

He hears the familiar beep of his mother's car, spots it pulling into the parking lot. Sonia is sitting

in the driver's seat, waving. Ben is next to her. This is the first time he's seeing Sonia since she and

Ben have announced their engagement. He decides that he will ask her to stop off at a liquor store so

he can buy some champagne. She steps out of the car, walking toward him. She is an attorney now,

working in an office in the Hancock building. Her hair is cut to her jaw. She's wearing an old blue

down jacket that Gogol had worn back in high school. And yet there is a new maturity in her face; he

can easily imagine her, a few years from now, with two children in the back seat. She gives him a hug.

For a moment they stand there with their arms around each other in the cold. "Welcome home,

Goggles," she says. For the last time, they assemble the artificial seven-foot tree, the branches colorcoded at their base. Gogol brings up the box from the basement. For decades the instructions have

been missing; each year they have to figure out the order in which the branches must be inserted, the

longest ones at the bottom, the smallest at the top. Sonia holds the pole, and Gogol and Ben insert

the branches. The orange go first, then the yellow, then the red and finally blue, the uppermost piece

slightly bent under the white speckled ceiling. They place the tree in front of the window, drawing apart

the curtains so that people passing by the house can see, as excited as they were when they were

children. They decorate it with ornaments made by Sonia and Gogol in elementary school:

construction paper candlesticks, Popsicle-stick god's-eyes, glitter-covered pinecones. A torn Banarasi

sari of Ashima's is wrapped around the base. At the top they put what they always do, a small plastic

bird covered with turquoise velvet, with brown wire claws.

Stockings are hung on nails from the mantel, the one put up for Moushumi last year now put up for

Ben. They drink the champagne out of Styrofoam cups, forcing Ashima to have some, too, and they

play the Perry Como Christmas tape his father always liked. They tease Sonia, telling Ben about the

year she had refused her gifts after taking a Hinduism class in college, coming home and protesting

that they weren't Christian. Early in the morning, his mother, faithful to the rules of Christmas her

P3. BDC A1. 5.2016

P3. Poetry and Prose

children had taught her when they were little, will wake up and fill the stockings, with gift certificates

to record stores, candy canes, mesh bags of chocolate coins. He can still remember the very first time

his parents had had a tree in the house, at his insistence, a plastic thing no larger than a table lamp,

displayed on top of the fireplace mantel. And yet its presence had felt colossal. How it had thrilled

him. He had begged them to buy it from the drugstore. He remembers decorating it clumsily with

garlands and tinsel and a string of lights that made his father nervous. In the evenings, until his father

came in and pulled out the plug, causing the tiny tree to go dark, Gogol would sit there. He

remembers the single wrapped gift that he had received, a toy that he'd picked out himself, his mother

asking him to stand by the greeting cards while she paid for it. "Remember when we used to put on

those awful flashing colored lights?" his mother says now when they are done, shaking her head. "I

didn't know a thing back then."

At seven-thirty the bell rings, and the front door is left open as people and cold air stream into the

house. Guests are speaking in Bengali, hollering, arguing, talking on top of one another, the sound of

their laughter filling the already crowded rooms. The croquettes are fried in crackling oil and

arranged with a red onion salad on plates. Sonia serves them with paper napkins. Ben, the jamai-tobe, is introduced to each of the guests. "I'll never keep all these names straight," he says at one point

to Gogol. "Don't worry, you'll never need to," Gogol says. These people, these honorary aunts and

uncles of a dozen different surnames, have seen Gogol grow, have surrounded him at his wedding,

his father's funeral. He promises to keep in touch with them now that his mother is leaving, not to

forget them. Sonia shows off her ring, six tiny diamonds surrounding an emerald, to the mashis, who

wear their red and green saris. "You will have to grow your hair for the wedding," they tell Sonia.

One of the meshos is sporting a Santa hat. They sit in the living room, on the furniture and on the

floor. Children drift down into the basement, the older ones to rooms upstairs. He recognizes his old

Monopoly game being played, the board in two pieces, the race car missing ever since Sonia dropped

it into the baseboard heater when she was little. Gogol does not know to whom these children belong

half the guests are people his mother has befriended in recent years, people who were at his

wedding but whom he does not recognize. People talk of how much they've come to love Ashima's

Christmas Eve parties, that they've missed them these past few years, that it won't be the same

without her.

Chapter 9

P3. BDC A1. 5.2016

Вам также может понравиться

- The Visitors: Gripping thriller, you won’t see the end comingОт EverandThe Visitors: Gripping thriller, you won’t see the end comingРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (93)

- Safe House PictureДокумент19 страницSafe House Picturemanghihigop ng lakasОценок пока нет

- The Quilt That Jack BuiltДокумент8 страницThe Quilt That Jack Builtapi-19787590Оценок пока нет

- Joyce Carol OatesДокумент12 страницJoyce Carol OatesomidamaniОценок пока нет

- The Safe House by Sandra Nicole Roldan: Sesame StreetДокумент2 страницыThe Safe House by Sandra Nicole Roldan: Sesame StreetJico MaravillasОценок пока нет

- The Safe House by Sandra Nicole RoldanДокумент4 страницыThe Safe House by Sandra Nicole RoldanKaye Anna Reyes100% (1)

- Nama: Sani Ratna Amelia NIM: 19033004Документ16 страницNama: Sani Ratna Amelia NIM: 19033004Nerissa NadhrotaОценок пока нет

- The Safe HouseДокумент4 страницыThe Safe HouseJo NabloОценок пока нет

- 21st Cent. Lit Lesson 6Документ31 страница21st Cent. Lit Lesson 6Jhayehl Prado SanicoОценок пока нет

- Peonies and Gorget Me NotsДокумент3 страницыPeonies and Gorget Me Notscristina_bartlebyОценок пока нет

- What Is A Short Story?Документ6 страницWhat Is A Short Story?ASTRAEAОценок пока нет

- ISL Entry Version 1Документ9 страницISL Entry Version 1Christopher HintonОценок пока нет

- The ReservoirДокумент20 страницThe ReservoirChristopher HintonОценок пока нет

- Drama Essay QuestionsДокумент1 страницаDrama Essay QuestionsChristopher HintonОценок пока нет

- The Life of Arthur MillerДокумент32 страницыThe Life of Arthur MillerChristopher HintonОценок пока нет

- Robert Sidney Sir Walter Ralegh Poet Sir Philip Sidney Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke Elizabeth I James IДокумент2 страницыRobert Sidney Sir Walter Ralegh Poet Sir Philip Sidney Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke Elizabeth I James IChristopher HintonОценок пока нет

- CIE. Workshop SummaryДокумент5 страницCIE. Workshop SummaryChristopher HintonОценок пока нет

- Emily Bronte-Wuthering Heights Either (A) by Careful Analysis of Heathcliff, Defend If He Is A Tyrant or A Victim of The Circumstances ThatДокумент3 страницыEmily Bronte-Wuthering Heights Either (A) by Careful Analysis of Heathcliff, Defend If He Is A Tyrant or A Victim of The Circumstances ThatChristopher HintonОценок пока нет

- God of Small Things: Daughters of Penelope Foundation Book Club Discussion QuestionsДокумент2 страницыGod of Small Things: Daughters of Penelope Foundation Book Club Discussion QuestionsChristopher HintonОценок пока нет

- JANE AUSTEN: Sense and Sensibility Either (A) by What Means and With What Effects Does Austen PortrayДокумент2 страницыJANE AUSTEN: Sense and Sensibility Either (A) by What Means and With What Effects Does Austen PortrayChristopher HintonОценок пока нет

- Passage Based Question: Text: Poetry Sixteenth and Seventeenth CenturyДокумент2 страницыPassage Based Question: Text: Poetry Sixteenth and Seventeenth CenturyChristopher HintonОценок пока нет

- LP HARTLEY: The Go BetweenДокумент2 страницыLP HARTLEY: The Go BetweenChristopher HintonОценок пока нет

- James Arthur - Mushrooms & MankindДокумент79 страницJames Arthur - Mushrooms & MankindPaola Diaz100% (1)

- Meaning of IslamДокумент24 страницыMeaning of IslamEjaz110100% (1)

- SP Jaiminicharadasaknraocolor1Документ22 страницыSP Jaiminicharadasaknraocolor1SaptarishisAstrology75% (4)

- Evil Tricks of ShaytanДокумент8 страницEvil Tricks of ShaytanSajid HolyОценок пока нет

- April FoolДокумент3 страницыApril FoolShahid KhanОценок пока нет

- Patriarch of Antioch FinalДокумент18 страницPatriarch of Antioch FinaljoesandrianoОценок пока нет

- Biometrics and The Mark of The BeastДокумент16 страницBiometrics and The Mark of The BeastTimothy100% (2)

- Pamela E. Cayabyab BSA 3DДокумент2 страницыPamela E. Cayabyab BSA 3DDioselle CayabyabОценок пока нет

- 26.02.2019 East Wharf BulkДокумент4 страницы26.02.2019 East Wharf BulkWajahat HasnainОценок пока нет

- Studies of Religion NotesДокумент26 страницStudies of Religion NotesYouieee100% (4)

- Front 1Документ15 страницFront 1Juan Pablo Pardo BarreraОценок пока нет

- Pauline @18Документ6 страницPauline @18CALMAREZ JOMELОценок пока нет

- Dream SuccessДокумент114 страницDream Successomegacleaning servicesОценок пока нет

- God Hears Our CriesДокумент3 страницыGod Hears Our CriesServant Of TruthОценок пока нет

- Flood Pre AdamicДокумент31 страницаFlood Pre AdamicEfraim MoraesОценок пока нет

- 1st Quarter 2016 Lesson 4 Powerpoint With Tagalog NotesДокумент25 страниц1st Quarter 2016 Lesson 4 Powerpoint With Tagalog NotesRitchie FamarinОценок пока нет

- Realism in R. K. Narayan's NovelsДокумент27 страницRealism in R. K. Narayan's NovelsSharifMahmud75% (4)

- Diogenes: Order The Status of Woman in Ancient India: Compulsives of The PatriarchalДокумент15 страницDiogenes: Order The Status of Woman in Ancient India: Compulsives of The PatriarchalSuvasreeKaranjaiОценок пока нет

- Pan InvalidДокумент203 страницыPan Invalidlovelyraajiraajeetha1999Оценок пока нет

- English ListДокумент8 страницEnglish Listapi-3799140100% (2)

- 201 - Agamas in Sri Vaishnavism - AgamaДокумент50 страниц201 - Agamas in Sri Vaishnavism - AgamaVinu GeorgeОценок пока нет

- Profetia Celor Zece Jubilee A Rabinului Iuda Ben Samuel-EnglezaДокумент6 страницProfetia Celor Zece Jubilee A Rabinului Iuda Ben Samuel-EnglezaCristiDucuОценок пока нет

- DVH Session 8Документ22 страницыDVH Session 8rajsab20061093100% (1)

- Prehispanic PeriodДокумент11 страницPrehispanic PeriodDaryl CastilloОценок пока нет

- Post Interaction SWISS EXPATSДокумент2 870 страницPost Interaction SWISS EXPATSWaf Etano100% (1)

- OPPT Definitions PDFДокумент2 страницыOPPT Definitions PDFAimee HallОценок пока нет

- Nature of The ConstitutionДокумент17 страницNature of The ConstitutionGrace MugorondiОценок пока нет

- 2000-2000, AA VV, Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae, enДокумент6 страниц2000-2000, AA VV, Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae, ensbravo2009Оценок пока нет

- Kenneth Watson, "The Center of Coleridge's Shakespeare Criticism"Документ4 страницыKenneth Watson, "The Center of Coleridge's Shakespeare Criticism"PACОценок пока нет