Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Así Se Extrajo Un Celular Que Se Tragó Un Hombre de 29 Años en Irlanda

Загружено:

Christian Tinoco SánchezОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Así Se Extrajo Un Celular Que Se Tragó Un Hombre de 29 Años en Irlanda

Загружено:

Christian Tinoco SánchezАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CASE REPORT OPEN ACCESS

International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 22 (2016) 8689

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Journal of Surgery Case Reports

journal homepage: www.casereports.com

An ingested mobile phone in the stomach may not be amenable to safe

endoscopic removal using current therapeutic devices: A case report

Obinna Obinwa , David Cooper, James M. ORiordan

Department of Surgery, The Adelaide and Meath Hospital, Dublin Incorporating the National Childrens Hospital, Tallaght, Dublin 24, Ireland

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Received 30 January 2016

Received in revised form 28 March 2016

Accepted 28 March 2016

Available online 1 April 2016

Keywords:

Foreign body removal

Stomach

Endoscopic devices

Mobile phone

Surgery

Case report

a b s t r a c t

INTRODUCTION: This case report is intended to inform clinicians, endoscopists, policy makers and industry

of our experience in the management of a rare case of mobile phone ingestion.

PRESENTATION OF CASE: A 29-year-old prisoner presented to the Emergency Department with vomiting,

ten hours after he claimed to have swallowed a mobile phone. Clinical examination was unremarkable.

Both initial and repeat abdominal radiographs eight hours later conrmed that the foreign body remained

in situ in the stomach and had not progressed along the gastrointestinal tract. Based on these ndings,

upper endoscopy was performed under general anaesthesia. The object could not be aligned correctly

to accommodate endoscopic removal using current retrieval devices. Following unsuccessful endoscopy,

an upper midline laparotomy was performed and the phone was delivered through an anterior gastrotomy, away from the pylorus. The patient made an uneventful recovery and underwent psychological

counselling prior to discharge.

DISCUSSION: In this case report, the use of endoscopy in the management when a conservative approach

fails is questioned. Can the current endoscopic retrieval devices be improved to limit the need for surgical

interventions in future cases?

CONCLUSION: An ingested mobile phone in the stomach may not be amenable for removal using the

current endoscopic retrieval devices. Improvements in overtubes or additional modications of existing

retrieval devices to ensure adequate alignment for removal without injuring the oesophagus are needed.

2016 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. on behalf of IJS Publishing Group Ltd. This is an open

access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

1. Introduction

Foreign body ingestion is a relatively common emergency problem. The majority of cases occur in the paediatric population [1,2].

Those with psychiatric disorders, developmental delay, alcohol

intoxication and prisoners are also at increased risk [36]. General clinical guidelines on diagnosis and management of ingested

foreign bodies have been published by the American Society for

Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) [6] and more recently, by the

European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) [7]. Specic guidelines for the management of gastric foreign bodies also

exist but are conned to common objects such as coins, magnets,

narcotic packets and disc batteries [6].

The management of a rare case of a patient who swallowed a

mobile phone with particular focus on the lessons learned from the

failed endoscopic management of the object is therefore presented

here. This manuscript is written in accordance with the CAse REport

Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: obinnaobinwa@rcsi.ie (O. Obinwa), cooperda@tcd.ie

(D. Cooper), James.ORiordan@amnch.ie (J.M. ORiordan).

(CARE) guidelines [8]. The report is intended to inform clinicians,

endoscopists and industry on our experience in the management

of this unusual case.

2. Presentation of case

A 29-year old male prisoner was brought in by ambulance to

the Emergency Department with a four-hour history of vomiting,

having claimed to have swallowed a foreign object six hours earlier

that day. He had no other associated symptoms. Of note, he had

complex psycho-social issues.

He was haemodynamically stable. Clinical examination was

unremarkable. All laboratory investigations were normal. An erect

chest X-ray partially showed the mobile phone in the epigastrium

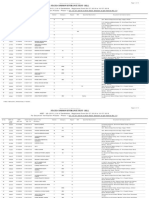

and there was no free air within the abdomen. An abdominal plain

lm revealed the complete device in the stomach (Fig. 1). The

patient was admitted and managed conservatively. He was kept nil

by mouth and commenced on intravenous uids and proton pump

inhibitors. A repeat abdominal radiograph, approximately eighteen

hours after the reported time of ingestion, showed that the mobile

phone remained in situ in the stomach and had not passed through

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.03.043

2210-2612/ 2016 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. on behalf of IJS Publishing Group Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

CASE REPORT OPEN ACCESS

O. Obinwa et al. / International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 22 (2016) 8689

Fig. 1. Plain lm abdomen showing the mobile phone.

the pylorus. At this time, the patient was consented for removal

under general anaesthesia (Fig. 2).

The patient was brought to the operating theatre, intubated and

the initial intervention was an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.

The ndings are shown in Fig. 3. Following failed attempts at endoscopic removal, using endoscopic snares, graspers, tripod forceps

and baskets, the endoscopic approach was abandoned. The mobile

phone could not be aligned correctly to allow for a safe retrieval

while limiting the potential harm to the oesophagus. The use of

overtube was not an option in this case due to the size of the

phone. An upper midline laparotomy was then performed and an

Alexis O Wound Protector was used to protect the wound. A gastrotomy (34 cm) was made in the anterior stomach away from

the pylorus. The phone was delivered through the gastrotomy by

manual manipulation assisted by Babcock forceps. The dimensions

of the foreign body were 68 23 11 mm. This was followed by a

two-layer gastrotomy closure, fascial and skin closure. A nasogastric tube was placed during the surgery and secured with a bridle.

The mobile phone was sent as a specimen for forensic examination.

Postoperatively, the patient received analgesia, two further

doses of antibiotics, and was kept nil by mouth for three days. He

received intravenous uids and proton pump inhibitors during the

period of fasting. The nasogastric tube remained in situ for a further

three days. He also received chest physiotherapy and was seen by

the psychiatrist before discharge. He passed a bowel motion on the

6th postoperative day and was discharged well on the 7th postoperative day. He was reviewed in the out-patient clinic four months

later. He was well with no symptoms at this point.

3. Discussion

Surgery (laparotomy or laparoscopy) is required in less than

1% of cases of foreign body ingestion as most will resolve with

87

conservative management or require endoscopy in approximately

1020% of cases [7].

Consenting the patient for laparotomy before the patient was

anaesthetised was considered to be an important learning point,

given the limitation of endoscopy in this case. This approach helped

to limit the dilemma of waking up the patient again to discuss

surgery or the pressurized attempt at taking out a maligned object

endoscopically with potential risks of injury to the oesophagus.

Similarly, if the intervention were to be carried out by a gastroenterologist under anaesthesia, we would recommend that the on-call

surgeon should be consulted before the patient is anaesthetized and

the surgeon should be in-house in case a surgical intervention is

required. Further, the site of incision, wound protection technique,

and outlined postoperative care limited the morbidities in this case.

Additional modern perspectives in the management also include

the psychological evaluation before discharge. As the patient was a

prisoner, the mobile phone had to be sent as a specimen for forensic

examination.

The failure of endoscopy to remove the mobile phone, in this

case, highlights the limitations of this approach. The traditional

sequence of conservative approach, endoscopy and surgery when

endoscopy fails is challenged. This observation has raised a new

question: should clinicians proceed directly to surgery when clinical observation fails in these cases or should endoscopy still be

attempted? The potential benet of endoscopy is that it may be

used as a minimally invasive bridge to surgery in cases of failed

conservative management. There were no specic guidelines in

the management of this case [6,7]. The object size described here

was within the upper limit of what would have also been considered for conservative management in prisoners [9]. The presence

of continued symptoms and failure to progress within 18 h of

conservative management were indications for proceeding with

endoscopic removal under general anaesthesia. In this case report,

upper GI Endoscopy also helped to conrm the diagnosis as well as

the objects failure to progress along the gastrointestinal tract.

Besides these clinical management pearls, there are also other

aspects of the endoscopic management of this patient which affect

industry and policy makers. Our experience in this case was that an

overtube was not an option due to the size of the object and we also

could not nd any other suitable retrieval devices that ensured correct alignment for endoscopic removal of the mobile phone through

the oesophagogastric junction. Needed now is the development

of self-expandable overtubes that can accommodate such objects

without risk of damaging the oesophagus. The alternative is for

industry to create or improve on existing retrieval devices to ensure

adequate alignment for removal as shown in Fig. 4. Such improvement, ideally should be tested in-vitro before being considered in

human subjects. Successful endoscopic removal of a foreign object

obviates the need for surgery and associated morbidity. There are

also potential health savings in terms of reduced length of stay and

health costs if surgery could be avoided.

Finally, unlike most other cases of foreign body ingestion, the

specic case of ingestion of mobile phone is underreported in

the literature. The only case report of mobile phone ingestion

which we could nd in PUBMED database was that of a 35year old intoxicated male with pharyngeal impaction by a mobile

phone who had the phone endoscopically removed under a general anaesthesia [10]. A few other anecdotal reports of mobile

phones lodged in the stomach exist in non-scientic literature,

but the current management, or quality improvement issues are

not entirely described. Besides detailing the full management of

such an under-reported case, we have described how our ndings

might affect clinicians, industry and policy makers.

CASE REPORT OPEN ACCESS

88

O. Obinwa et al. / International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 22 (2016) 8689

Fig. 2. Timeline.

4. Conclusion

An ingested mobile phone in the stomach may not be amenable

for safe removal using the current endoscopic retrieval devices.

Therefore we recommend that all patients undergoing endoscopic

removal of a mobile phone should be consented for a laparotomy.

As well as this, there is need for the development of self-expandable

overtubes or additional improvement on existing retrieval devices

to ensure adequate alignment for removal without risks of damage

to the oesophagus.

Ethical approval

An ethical approval was not required.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for

publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy

of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief

of this journal on request.

Submission declaration

Conict of interest

The authors have no conicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The authors have no extra or intra-institutional funding to

declare.

The authors declare: that the work described has not been published previously, that it is not under consideration for publication

elsewhere, that its publication is approved by all authors and tacitly or explicitly by the responsible authorities where the work was

carried out, and that, if accepted, it will not be published elsewhere

including electronically in the same form, in English or in any other

language, without the written consent of the copyright holder.

CASE REPORT OPEN ACCESS

O. Obinwa et al. / International Journal of Surgery Case Reports 22 (2016) 8689

89

Author contributors

O.O. and D.C. contributed equally in this case report. O.O. and

D.C. conceived the initial idea of the study. J.O.R., O.O., and D.C.

acquired the data for publication. O.O. and D.C. drafted the article,

and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the nal version of the manuscript to be

submitted.

Guarantor

Mr James ORiordan, Consultant General and Colorectal Surgeon,

Adelaide and Meath Hospital, Incorporating the National Childrens

Hospital, Tallaght, Dublin 24, Ireland.

References

Fig. 3. Gastroscopy showing the mobile phonein the stomach.

[1] W. Cheng, P.K. Tam, Foreign-body ingestion in children: experience with 1265

cases, J. Pediatr. Surg. 34 (1999) 14721476.

[2] E. Panieri, D.H. Bass, The management of ingested foreign bodies in

childrena review of 663 cases, Eur. J. Emerg. Med. 2 (1995) 8387.

[3] R. Palta, A. Sahota, A. Bemarki, P. Salama, N. Simpson, L. Laine, Foreign-body

ingestion: characteristics and outcomes in a lower socioeconomic population

with predominantly intentional ingestion, Gastrointest. Endosc. 69 (2009)

426433.

[4] S.T. Weiland, M.J. Schurr, Conservative management of ingested foreign

bodies, J. Gastrointest. Surg. 6 (2002) 496500.

[5] K.E. Blaho, K.S. Merigian, S.L. Winbery, L.J. Park, M. Cockrell, Foreign body

ingestions in the Emergency Department: case reports and review of

treatment, J. Emerg. Med. 16 (1998) 2126.

[6] S.O. Ikenberry, T.L. Jue, M.A. Anderson, V. Appalaneni, S. Banerjee, T.

Ben-Menachem, et al., Management of ingested foreign bodies and food

impactions, Gastrointest. Endosc. 73 (2011) 10851091.

[7] M. Birk, P. Bauerfeind, P.H. Deprez, M. Hafner, D. Hartmann, C. Hassan, et al.,

Removal of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract in adults:

European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline,

Endoscopy 48 (2016) 18.

[8] J.J. Gagnier, G. Kienle, D.G. Altman, D. Moher, H. Sox, D. Riley, The CARE

guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development, J.

Clin. Epidemiol. 67 (2014) 4651.

[9] Y. Ribas, D. Ruiz-Luna, M. Garrido, J. Bargallo, F. Campillo, Ingested foreign

bodies: do we need a specic approach when treating inmates, Am. Surg. 80

(2014) 131137.

[10] M.M. Ali, K. Bahl, M. Dross, S. Farooqui, P. Dross, Accidental cell phone

ingestion with pharyngeal impaction, Del. Med. J. 86 (2014) 277279.

Fig. 4. Ideal endoscopic alignment for safe removal.

Open Access

This article is published Open Access at sciencedirect.com. It is distributed under the IJSCR Supplemental terms and conditions, which

permits unrestricted non commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are

credited.

Вам также может понравиться

- Los Empleadores Más Atractivos Del Mundo en 2017Документ26 страницLos Empleadores Más Atractivos Del Mundo en 2017Christian Tinoco SánchezОценок пока нет

- Ufo Highlights Guide 2013Документ12 страницUfo Highlights Guide 2013NRCОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- Mocion Presentada en El Congreso Donde Se Solicita La Vacancia Del Presidente PPKДокумент4 страницыMocion Presentada en El Congreso Donde Se Solicita La Vacancia Del Presidente PPKChristian Tinoco SánchezОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- GPI 2017 Report 1Документ140 страницGPI 2017 Report 1Montevideo PortalОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Índice de Paz Mundial 2013Документ106 страницÍndice de Paz Mundial 2013Christian Tinoco SánchezОценок пока нет

- Worlds Healthiest CountriesДокумент5 страницWorlds Healthiest CountriesMD PraxОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Social Progress Index 2016Документ147 страницSocial Progress Index 2016Christian Tinoco Sánchez100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Full Report Energy Trilemma Index 2016Документ147 страницFull Report Energy Trilemma Index 2016Christian Tinoco SánchezОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Peligros de La Percepción 2016Документ30 страницPeligros de La Percepción 2016Christian Tinoco SánchezОценок пока нет

- Fallo de La Haya: Este Es El DocumentoДокумент71 страницаFallo de La Haya: Este Es El DocumentoLa RepúblicaОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Nation Brands Finance 2015Документ24 страницыNation Brands Finance 2015Christian Tinoco SánchezОценок пока нет

- FutureBrand's Country Brand IndexДокумент107 страницFutureBrand's Country Brand IndexskiftnewsОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Reply of The Government of PeruДокумент360 страницReply of The Government of PeruChristian Tinoco SánchezОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Rejoinder of The Government of ChileДокумент381 страницаRejoinder of The Government of ChileChristian Tinoco SánchezОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Counter-Memorial of The Government of ChileДокумент407 страницCounter-Memorial of The Government of ChileChristian Tinoco SánchezОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Memorial of The Government of PeruДокумент302 страницыMemorial of The Government of PeruChristian Tinoco SánchezОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Best Global Brands 2012Документ75 страницBest Global Brands 2012Christian Tinoco SánchezОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- Presentación de Peter Tomka, Presidente de La Corte de La HayaДокумент5 страницPresentación de Peter Tomka, Presidente de La Corte de La HayaChristian Tinoco SánchezОценок пока нет

- Eurobrand 2012 Global Top 100Документ10 страницEurobrand 2012 Global Top 100robinwautersОценок пока нет

- Yokohama Living GuideДокумент102 страницыYokohama Living GuideKriz EarnestОценок пока нет

- Seneca Rachel ResumeДокумент1 страницаSeneca Rachel Resumeapi-259257079Оценок пока нет

- FijiTimes - May 17 2013Документ48 страницFijiTimes - May 17 2013fijitimescanadaОценок пока нет

- Astron Hospital and Healthcare Consultants Pvt. Ltd.Документ22 страницыAstron Hospital and Healthcare Consultants Pvt. Ltd.Rekha ChakrabartiОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Boast 1 - Fragility Hip Fractures PDFДокумент1 страницаBoast 1 - Fragility Hip Fractures PDFSam BarnesОценок пока нет

- Accomplishment ReportДокумент8 страницAccomplishment ReportKevin Fernandez MendioroОценок пока нет

- List of Approved Hospital For Cashless Facility Under New Medical Insurance Scheme of IBAДокумент332 страницыList of Approved Hospital For Cashless Facility Under New Medical Insurance Scheme of IBAAnup PrakashОценок пока нет

- Status Epilepticus What's New For The IntensivistДокумент11 страницStatus Epilepticus What's New For The IntensivistBenjamínGalvanОценок пока нет

- Hospital Department Role Play Script in EnglishДокумент4 страницыHospital Department Role Play Script in EnglishAmita putriОценок пока нет

- Factors Affecting Location of Multi Specialty HospitalДокумент32 страницыFactors Affecting Location of Multi Specialty HospitalfrancisОценок пока нет

- PHD ProposalДокумент20 страницPHD ProposalMandusОценок пока нет

- ..... The Story: Stoica (Vuta) Ileana-Magdalena Engleza - Germana Anul IiiДокумент4 страницы..... The Story: Stoica (Vuta) Ileana-Magdalena Engleza - Germana Anul Iiiileana- magdalena stoicaОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Productivity ImprovementДокумент10 страницProductivity ImprovementBudi PermanaОценок пока нет

- Discharge SummaryДокумент9 страницDischarge SummaryAllwinОценок пока нет

- Proposed 100-Bed Hospital Architectural BriefДокумент2 страницыProposed 100-Bed Hospital Architectural Briefarshad khanОценок пока нет

- Ramachari Anaesthesiologist-Brief BiodataДокумент1 страницаRamachari Anaesthesiologist-Brief Biodatadr_saketram6146Оценок пока нет

- Bahan Pagets Disease of MaxillaДокумент3 страницыBahan Pagets Disease of MaxillayuniОценок пока нет

- Therapeutic CommunicationДокумент4 страницыTherapeutic CommunicationLloyd Rafael Estabillo100% (1)

- Completion of the Partogram in PregnancyДокумент9 страницCompletion of the Partogram in Pregnancyfei cuaОценок пока нет

- Community Quarantine RecommendationsДокумент5 страницCommunity Quarantine RecommendationsRapplerОценок пока нет

- Titles of CandidatesДокумент13 страницTitles of CandidatessanolОценок пока нет

- Sneha Nirav Marjadi V State of Maharashtra Ors and Connected PetitionsДокумент16 страницSneha Nirav Marjadi V State of Maharashtra Ors and Connected PetitionsNek PuriОценок пока нет

- Patan Academy of Health Sciences: Pcrlab@pahs - Edu.np Ewarsedcd@gmail - Co Pcrlab@pahs - Edu.npДокумент2 страницыPatan Academy of Health Sciences: Pcrlab@pahs - Edu.np Ewarsedcd@gmail - Co Pcrlab@pahs - Edu.npBhageshwar Chaudhary100% (1)

- SegHIS NormalДокумент51 страницаSegHIS Normalkaliyasa0% (1)

- Carriere® SLX Self-Ligating Bracket BrochureДокумент8 страницCarriere® SLX Self-Ligating Bracket BrochureOrtho Organizers100% (1)

- NP2 Nursing Board Exam June 2008 Answer KeyДокумент14 страницNP2 Nursing Board Exam June 2008 Answer KeyBettina SanchezОценок пока нет

- MGM 5Документ17 страницMGM 5Paul KwongОценок пока нет

- Respiratory Status of Adult Patients in The Postoperative Period of Thoracic or Upper Abdominal SurgeriesДокумент8 страницRespiratory Status of Adult Patients in The Postoperative Period of Thoracic or Upper Abdominal SurgeriesDimitreОценок пока нет

- Case StudyДокумент62 страницыCase StudyIyalisaiVijay0% (1)

- Sasha Chavezs ResumeДокумент2 страницыSasha Chavezs Resumeapi-478478393Оценок пока нет

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionОт EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (402)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingОт EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (4)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityОт EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (13)