Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

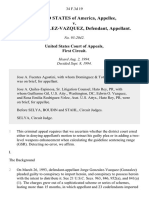

United States v. Burgos-Figueroa, 1st Cir. (2015)

Загружено:

Scribd Government DocsИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

United States v. Burgos-Figueroa, 1st Cir. (2015)

Загружено:

Scribd Government DocsАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

United States Court of Appeals

For the First Circuit

No. 13-2379

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellee,

v.

JUSTO L. BURGOS-FIGUEROA,

Defendant, Appellant.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF PUERTO RICO

[Hon. Aida M. Delgado-Coln, U.S. District Judge]

Before

Thompson, Selya and Kayatta,

Circuit Judges.

Anita Hill Adames on brief for appellant.

Rosa Emilia Rodrguez-Vlez, United States Attorney, and

Nelson Prez-Sosa, Assistant United States Attorney, Chief,

Appellate Division, on brief for appellee.

February 13, 2015

SELYA, Circuit Judge.

appeal.

In

it,

This is a single-issue sentencing

defendant-appellant

Justo

L.

Burgos-Figueroa

assigns error to the district court's imposition of a two-level

sentencing enhancement reflecting the possession of a dangerous

weapon

during

drug-trafficking

conspiracy.

See

USSG

2D1.1(b)(1).

It is common ground that a sentencing enhancement must be

supported by a preponderance of the evidence. See United States v.

McDonald, 121 F.3d 7, 9 (1st Cir. 1997). The facts undergirding an

enhancement need not be established by direct evidence but, rather,

may be inferred from circumstantial evidence. See United States v.

Cruz, 120 F.3d 1, 4 (1st Cir. 1997) (en banc).

and,

after

careful

consideration,

we

This is such a case

uphold

the

disputed

enhancement.

A synopsis affords the necessary perspective. On October

26, 2012, a federal grand jury sitting in the District of Puerto

Rico returned a four-count indictment against the appellant.

parties

later

Agreement).

entered

into

written

plea

agreement

The

(the

Pursuant to the Agreement, the appellant pleaded

guilty to count 1 of the indictment (which charged him with

conspiring to distribute substantial quantities of cocaine, heroin,

and marijuana, see 21 U.S.C. 841(a)(1), 846), and the government

agreed to dismiss the remaining counts.

In the Agreement, the

parties stipulated to a series of guidelines calculations.

-2-

These

stipulations envisioned only two adjustments to the appellant's

offense level: a two-level enhancement for the appellant's role as

a leader or manager of the conspiracy, see USSG 3B1.1(c), and a

three-level reduction for acceptance of responsibility, see id.

3E1.1(b).

Following

customary

practice,

the

probation

office

prepared a presentence investigation report (PSI Report).

The

Report disclosed that the appellant, along with at least thirty-two

confederates,

had

participated

in

sprawling

conspiracy

to

distribute an array of drugs from various drug points in the

Pastillo Ward in Juana Diaz, Puerto Rico.

The conspiracy was

organized along hierarchical lines, allocating varying degrees of

authority among leaders, drug point owners, enforcers, sellers,

runners, and facilitators.

As a drug point owner, the appellant

supervised other members of the conspiracy and supplied controlled

substances

to

coconspirators

for

distribution

and

sale.

Of

particular pertinence for present purposes, the PSI Report made

pellucid that the conspiracy involved the use of firearms as a

means of protecting the enterprise and its wares against rival

organizations and gangs.

The appellant did not object either to

this factual recital or to any other factual recital explicated in

the PSI Report.

Based on the facts developed in the PSI Report, the

probation office recommended, inter alia, a two-level enhancement

-3-

for

possessing

2D1.1(b)(1).

firearms

during

the

conspiracy.

See

id.

At the disposition hearing, the appellant opposed

this recommendation, and the government took no position concerning

it.

The appellant argued that the weapons enhancement did not

apply because the record contained no direct evidence that either

he or any person working under his immediate supervision possessed

any firearms.

The district court rejected this argument.

The

court found that, as the owner of a drug point and a leader of the

conspiracy, the appellant reasonably could have foreseen that his

coconspirators and subordinates would possess guns.

The court

proceeded to impose the enhancement, which had the effect of

elevating the appellant's guideline sentencing range to 135-168

months. After considering the appellant's personal characteristics

and the nature and circumstances of the offense of conviction, the

court

sentenced

immurement.

the

appellant

to

serve

168-month

term

of

This timely appeal ensued.

In this venue, the appellant strives to convince us that

it

was

error

for

the

district

court

to

impose

the

weapons

enhancement simply because others carried firearms during the

conspiracy.

We are not persuaded.

The sentencing guidelines authorize a two-level increase

in a defendant's offense level "[i]f a dangerous weapon (including

a firearm) was possessed" during the course of a drug-trafficking

conspiracy.

Id.

For this enhancement to attach, a defendant need

-4-

not be caught red-handed: the enhancement applies not only where a

defendant himself possessed a firearm but also where it was

reasonably foreseeable to the defendant that firearms would be

possessed

by

others

during

the

conspiracy.

See

id.

1B1.3(a)(1)(B); United States v. Bianco, 922 F.2d 910, 912 (1st

Cir. 1991).

In this instance, the sentencing court found that the

appellant reasonably could have foreseen that his coconspirators

and subordinates would possess firearms to protect the drugtrafficking enterprise.

We review that factual finding for clear

error, see United States v. Quiones-Medina, 553 F.3d 19, 23 (1st

Cir.

2009),

mindful

that

when

the

record

plausibly

supports

competing inferences, a sentencing court's choice among them cannot

be clearly erroneous, see United States v. Ruiz, 905 F.2d 499, 508

(1st Cir. 1990).

We discern no clear error here.

A sentencing court may consider facts set forth in

unchallenged portions of the PSI Report as reliable evidence.

See

United States v. Olivero, 552 F.3d 34, 39 (1st Cir. 2009); Cruz,

120 F.3d at 2.

Here, that constellation of facts made plain that

members of the conspiracy regularly carried firearms for the

purpose of protecting drug points (including the appellant's drug

point).

What is more, turf wars raged; and members of the

conspiracy participated from time to time in shoot-outs with rival

gangs.

-5-

Given this scenario, the district court could plausibly

infer as it did that the appellant, who was a drug point owner

and

leader

of

the

conspiracy

whose

duties

included

the

supervision of others, knew of these practices and incidents and

could foresee their continuation.

See United States v. Vzquez-

Rivera, 470 F.3d 443, 447 (1st Cir. 2006) (finding possession of

firearms reasonably foreseeable where defendant was manager of drug

point and intimately involved in its operations).

Indeed, with

firefights erupting as his organization waged war with rival gangs,

it beggars credulity to suggest that the appellant was blissfully

unaware that his coconspirators and subordinates carried firearms.

This

inference

in

is

large

bolstered

amounts

the

fact

the

cocaine,

and

dealt

marijuana.

When large quantities of drugs are involved, firearms

24; Bianco, 922 F.2d at 912.

heroin,

that

conspiracy

are common tools of the trade.

of

by

See Quiones-Medina, 553 F.3d at

This circumstance lends credence to

the inference that the appellant reasonably could have foreseen the

use of firearms in the operation of the conspiracy.

See United

States v. Sostre, 967 F.2d 728, 731-32 (1st Cir. 1992); Bianco, 922

F.2d at 912.

In an effort to blunt the force of this reasoning, the

appellant

complains

that

the

district

court

mentioned

three

coconspirators who possessed firearms without making any finding

that

the

appellant

had

any

specific

-6-

connection

to

those

individuals.

This complaint is unfounded.

Reading the court's

statements in context, we think it clear that the court was simply

making an observation about the appellant's role in the conspiracy

as compared to the roles of other coconspirators.

And in all

events, the court was not required to find that the appellant knew

that any particular coconspirator possessed a firearm at any given

time.

See, e.g., Vzquez-Rivera, 470 F.3d at 447.

The appellant also suggests that the district court's

determination is somehow undermined by the fact that he was not

charged in the weapons count, see 18 U.S.C. 924(c)(1)(A), (o),

while other conspirators were so charged. But this is a non-issue:

whether or not the appellant himself was charged with a firearms

violation is beside the point. What counts is that the court below

supportably

determined

that

the

use

of

weapons

during

the

conspiracy was reasonably foreseeable to the appellant. See United

States v. Watts, 519 U.S. 148, 154 (1997) (per curiam) (recognizing

that uncharged conduct can serve as the basis for a sentencing

enhancement); United States v. Smith, 267 F.3d 1154, 1165 (D.C.

Cir. 2001) (same).

We need go no further.

Although the record contains no

evidence that the appellant himself ever carried a firearm, that

kind of proof is not essential for a weapons enhancement under USSG

2D1.1(b)(1).

The enhancement may be based on a finding that the

appellant reasonably could have foreseen firearms possession by

-7-

others during the conspiracy.

Such a finding may be premised on

circumstantial evidence, see United States v. Paneto, 661 F.3d 709,

716 (1st Cir. 2011), and the circumstantial evidence here is more

than sufficient to warrant application of the enhancement.

Affirmed.

-8-

Вам также может понравиться

- United States of America Vs Michael Lee Haddock Aka Mr. MikeДокумент14 страницUnited States of America Vs Michael Lee Haddock Aka Mr. MikeSandra PorterОценок пока нет

- Nike Code of ConductДокумент1 страницаNike Code of Conductapi-300476144Оценок пока нет

- Ontario Faclities Human Rights Form 1CДокумент5 страницOntario Faclities Human Rights Form 1CCheryl BensonОценок пока нет

- United States v. Darrell Walter Preakos, 907 F.2d 7, 1st Cir. (1990)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Darrell Walter Preakos, 907 F.2d 7, 1st Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Hernandez-Vega, 235 F.3d 705, 1st Cir. (2000)Документ12 страницUnited States v. Hernandez-Vega, 235 F.3d 705, 1st Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Charles Courtland Smith, A/K/A Deanie Smith, 931 F.2d 888, 4th Cir. (1991)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Charles Courtland Smith, A/K/A Deanie Smith, 931 F.2d 888, 4th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitДокумент13 страницUnited States Court of Appeals: For The First CircuitScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Roman-Diaz, 1st Cir. (2017)Документ15 страницUnited States v. Roman-Diaz, 1st Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Ortiz Torres v. United States, 42 F.3d 1384, 1st Cir. (1994)Документ6 страницOrtiz Torres v. United States, 42 F.3d 1384, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Ruben Perez-Ruiz, 4th Cir. (2015)Документ9 страницUnited States v. Ruben Perez-Ruiz, 4th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Anthony Paccione and Michael Paccione, 202 F.3d 622, 2d Cir. (2000)Документ5 страницUnited States v. Anthony Paccione and Michael Paccione, 202 F.3d 622, 2d Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Cecilio F. McDonald, 121 F.3d 7, 1st Cir. (1997)Документ7 страницUnited States v. Cecilio F. McDonald, 121 F.3d 7, 1st Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. McDonald, 1st Cir. (1997)Документ17 страницUnited States v. McDonald, 1st Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Santiago-Rivera, 1st Cir. (2014)Документ12 страницUnited States v. Santiago-Rivera, 1st Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Rafael Ventura, 353 F.3d 84, 1st Cir. (2003)Документ11 страницUnited States v. Rafael Ventura, 353 F.3d 84, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Castro-Perez, 10th Cir. (2014)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Castro-Perez, 10th Cir. (2014)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Gianquitto, 89 F.3d 824, 1st Cir. (1996)Документ5 страницUnited States v. Gianquitto, 89 F.3d 824, 1st Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Arias, 14 F.3d 45, 1st Cir. (1994)Документ5 страницUnited States v. Arias, 14 F.3d 45, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Nicholas Bianco, United States of America v. Daniel Thomas Feeney, 922 F.2d 910, 1st Cir. (1991)Документ7 страницUnited States v. Nicholas Bianco, United States of America v. Daniel Thomas Feeney, 922 F.2d 910, 1st Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Figueroa v. United States, 19 F.3d 7, 1st Cir. (1994)Документ3 страницыFigueroa v. United States, 19 F.3d 7, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Juan Carols Arroyo-Reyes, 32 F.3d 561, 1st Cir. (1994)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Juan Carols Arroyo-Reyes, 32 F.3d 561, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Valdez-Bretones, 68 F.3d 455, 1st Cir. (1995)Документ5 страницUnited States v. Valdez-Bretones, 68 F.3d 455, 1st Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Garcia, 10th Cir. (1998)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Garcia, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Omar Abdulla Ali, 110 F.3d 60, 4th Cir. (1997)Документ3 страницыUnited States v. Omar Abdulla Ali, 110 F.3d 60, 4th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Perez-Ruiz, 353 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (2003)Документ20 страницUnited States v. Perez-Ruiz, 353 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Felix-Santos, 50 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (1995)Документ4 страницыUnited States v. Felix-Santos, 50 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Cornelius Snow, 911 F.2d 726, 4th Cir. (1990)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Cornelius Snow, 911 F.2d 726, 4th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Rivera-Alicea, 205 F.3d 480, 1st Cir. (2000)Документ10 страницUnited States v. Rivera-Alicea, 205 F.3d 480, 1st Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- UNITED STATES of America v. Charles NAVARRO, AppellantДокумент15 страницUNITED STATES of America v. Charles NAVARRO, AppellantScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Tarik S. Lane, 4th Cir. (1999)Документ3 страницыUnited States v. Tarik S. Lane, 4th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Alfred Sarno, 456 F.2d 875, 1st Cir. (1972)Документ4 страницыUnited States v. Alfred Sarno, 456 F.2d 875, 1st Cir. (1972)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Brewster, 1 F.3d 51, 1st Cir. (1993)Документ7 страницUnited States v. Brewster, 1 F.3d 51, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Lizardo-Figueroa, 10th Cir. (2008)Документ10 страницUnited States v. Lizardo-Figueroa, 10th Cir. (2008)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Rodriguez-Adorno, 1st Cir. (2017)Документ17 страницUnited States v. Rodriguez-Adorno, 1st Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Robert Medley, 976 F.2d 728, 4th Cir. (1992)Документ5 страницUnited States v. Robert Medley, 976 F.2d 728, 4th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Wipp-Kelley, 1st Cir. (2017)Документ9 страницUnited States v. Wipp-Kelley, 1st Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Wipp-Kelley, 1st Cir. (2017)Документ9 страницUnited States v. Wipp-Kelley, 1st Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Gonzalez Vazquez, 34 F.3d 19, 1st Cir. (1994)Документ10 страницUnited States v. Gonzalez Vazquez, 34 F.3d 19, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Turbides-Leonardo, 468 F.3d 34, 1st Cir. (2006)Документ10 страницUnited States v. Turbides-Leonardo, 468 F.3d 34, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Ortiz-Rodriguez, 1st Cir. (2015)Документ11 страницUnited States v. Ortiz-Rodriguez, 1st Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Don Allen Parker, 604 F.2d 1327, 10th Cir. (1979)Документ5 страницUnited States v. Don Allen Parker, 604 F.2d 1327, 10th Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Filed: Patrick FisherДокумент7 страницFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Marrero-Ortiz, 160 F.3d 768, 1st Cir. (1998)Документ14 страницUnited States v. Marrero-Ortiz, 160 F.3d 768, 1st Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Gary Howard Kellerman, 432 F.2d 371, 10th Cir. (1971)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Gary Howard Kellerman, 432 F.2d 371, 10th Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Desantiago-Flores, 10th Cir. (1997)Документ17 страницUnited States v. Desantiago-Flores, 10th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Murphy-Cordero, 1st Cir. (2013)Документ8 страницUnited States v. Murphy-Cordero, 1st Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Michael C. Richburg, United States of America v. Michael C. Richburg, 32 F.3d 563, 4th Cir. (1994)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Michael C. Richburg, United States of America v. Michael C. Richburg, 32 F.3d 563, 4th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Filed: Patrick FisherДокумент7 страницFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Maldonado-Garcia, 446 F.3d 227, 1st Cir. (2006)Документ7 страницUnited States v. Maldonado-Garcia, 446 F.3d 227, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Rodriguez, 336 F.3d 67, 1st Cir. (2003)Документ7 страницUnited States v. Rodriguez, 336 F.3d 67, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. John J. O'COnnOr, 580 F.2d 38, 2d Cir. (1978)Документ9 страницUnited States v. John J. O'COnnOr, 580 F.2d 38, 2d Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Stanley Rodgers, 911 F.2d 726, 4th Cir. (1990)Документ4 страницыUnited States v. Stanley Rodgers, 911 F.2d 726, 4th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Wilfredo Barreto, 968 F.2d 1210, 1st Cir. (1992)Документ8 страницUnited States v. Wilfredo Barreto, 968 F.2d 1210, 1st Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Ricardo Jose Noche, 979 F.2d 844, 1st Cir. (1992)Документ3 страницыUnited States v. Ricardo Jose Noche, 979 F.2d 844, 1st Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Mansur-Ramos, 348 F.3d 29, 1st Cir. (2003)Документ5 страницUnited States v. Mansur-Ramos, 348 F.3d 29, 1st Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Smith, 10th Cir. (1999)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Smith, 10th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Shorter, 4th Cir. (1999)Документ5 страницUnited States v. Shorter, 4th Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Ruben Diaz, 916 F.2d 655, 11th Cir. (1990)Документ6 страницUnited States v. Ruben Diaz, 916 F.2d 655, 11th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Ortiz-Santiago, 211 F.3d 146, 1st Cir. (2000)Документ9 страницUnited States v. Ortiz-Santiago, 211 F.3d 146, 1st Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Vega-Figueroa, 234 F.3d 744, 1st Cir. (2000)Документ18 страницUnited States v. Vega-Figueroa, 234 F.3d 744, 1st Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Steve Richards, 737 F.2d 1307, 4th Cir. (1984)Документ5 страницUnited States v. Steve Richards, 737 F.2d 1307, 4th Cir. (1984)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ20 страницUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Coyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ7 страницCoyle v. Jackson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ22 страницыConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ4 страницыUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ9 страницUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ21 страницаCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ25 страницPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitДокумент14 страницPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ50 страницUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitДокумент10 страницPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ4 страницыUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ15 страницApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ100 страницHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ25 страницUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitДокумент24 страницыPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ27 страницUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ9 страницNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ5 страницUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ25 страницUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ7 страницUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ2 страницыUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ15 страницUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Jimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ5 страницJimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ5 страницPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitДокумент17 страницPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Northern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ10 страницNorthern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Chevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ42 страницыChevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Coburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ9 страницCoburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Robles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ5 страницRobles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- United States v. Purify, 10th Cir. (2017)Документ4 страницыUnited States v. Purify, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Argumentasi HukumДокумент65 страницArgumentasi HukumBudi HerudiОценок пока нет

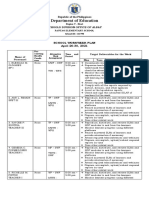

- WWP April 26 30 Pantao EsДокумент8 страницWWP April 26 30 Pantao EsClerica RealingoОценок пока нет

- Filipino Kinship and FamilyДокумент20 страницFilipino Kinship and FamilyAlyssa Mari ReyesОценок пока нет

- Format of Suit of Dissolution of Marriage On The Basis of KhulaДокумент4 страницыFormat of Suit of Dissolution of Marriage On The Basis of KhulaHome TuitionОценок пока нет

- Mendoza-Ong v. SandiganbayanДокумент5 страницMendoza-Ong v. SandiganbayanmisterdodiОценок пока нет

- Sapin Law II The New French Legal Framework For The Fight Against CorruptionДокумент7 страницSapin Law II The New French Legal Framework For The Fight Against CorruptionSneha SharmaОценок пока нет

- Double InsuranceДокумент4 страницыDouble Insurancechisel_159100% (1)

- Labor Law Study GuideДокумент25 страницLabor Law Study GuidebutterflygigglesОценок пока нет

- 6 Chapter 03 Ethical Issues in Indian Advertising PDFДокумент41 страница6 Chapter 03 Ethical Issues in Indian Advertising PDFDavid BassОценок пока нет

- Case Digests 2018.05.07Документ33 страницыCase Digests 2018.05.07jdz1988Оценок пока нет

- Group 7 Final Research PaperДокумент7 страницGroup 7 Final Research PaperMary Joy CartallaОценок пока нет

- Spes Successionis By-Diksha Iiird Semester Chanakya National Law UniversityДокумент12 страницSpes Successionis By-Diksha Iiird Semester Chanakya National Law Universitydiksha67% (3)

- C - 69 Moday vs. CAДокумент11 страницC - 69 Moday vs. CAcharmssatellОценок пока нет

- Permanant Exemption ApplicationДокумент3 страницыPermanant Exemption ApplicationVagisha KocharОценок пока нет

- 2 Digest Pealber V Ramos G R No 178645 577 SCRA 509 30 January 2009Документ2 страницы2 Digest Pealber V Ramos G R No 178645 577 SCRA 509 30 January 2009Aleph Jireh100% (1)

- 1 Us VS Go ChicoДокумент6 страниц1 Us VS Go ChicoPaul100% (1)

- Crim 3Документ142 страницыCrim 3Earl NuydaОценок пока нет

- BSP Circular No. 805-13: Senior Citizens Priority Lane in BSP Supervised Financial InstitutionsДокумент2 страницыBSP Circular No. 805-13: Senior Citizens Priority Lane in BSP Supervised Financial InstitutionsAndrei Anne PalomarОценок пока нет

- Leg Eth Mikka PDFДокумент1 страницаLeg Eth Mikka PDFMikkaEllaAnclaОценок пока нет

- National Trucking V Lorenzo ShippingДокумент2 страницыNational Trucking V Lorenzo ShippingPMVОценок пока нет

- Cases 26 35Документ5 страницCases 26 35Angelina Villaver ReojaОценок пока нет

- SSK Parts V SSK CamasДокумент1 страницаSSK Parts V SSK CamasKat Jolejole100% (1)

- Dissolution by Court (S 44)Документ2 страницыDissolution by Court (S 44)chetna raghuwanshiОценок пока нет

- Indemnification Clauses: A Practical Look at Everyday IssuesДокумент149 страницIndemnification Clauses: A Practical Look at Everyday IssuesewhittemОценок пока нет

- Revisiting The Guidance AdvocateДокумент52 страницыRevisiting The Guidance AdvocateDLareg ZedLav EtaLamОценок пока нет

- AwawawДокумент1 страницаAwawawPatrickHidalgoОценок пока нет

- Code of Ethics: Health Education & Behavior, Vol. 29 (1) : 11 (February 2002)Документ1 страницаCode of Ethics: Health Education & Behavior, Vol. 29 (1) : 11 (February 2002)afsdsaadsОценок пока нет

- Informatica v. ProtegrityДокумент8 страницInformatica v. ProtegrityPatent LitigationОценок пока нет