Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

03 Jadumani PDF

Загружено:

Nulul Ci LoolyИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

03 Jadumani PDF

Загружено:

Nulul Ci LoolyАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Journal of Academia and Industrial Research (JAIR)

Volume 3, Issue 5 October 2014

215

ISSN: 2278-5213

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Etiology of Adult Patients of Portal Hypertension and Evaluation of

their Clinical Presentations

1,2

Jadumani Nayak1, Smaraka R. Panda2 and Sudeshna Behera3*

3

Dept. of Medicine, Dept. of Biochemistry, SCB Medical College, Cuttack, Odisha, India

drjadumani@gmail.com, drsmarak@gmail.com, 4sudeshna@gmail.com*; +91 9238826182

______________________________________________________________________________________________

Abstract

There are only few studies on etiology of Portal Hypertension (PH) among adults in India. Hence, this study

was conducted to assess the etiology of portal hypertension in adults and evaluate their clinical

presentations. The study enrolled 142 cases of portal hypertension patients admitted to the Dept. of General

Medicine and Hepatology unit, SCB Medical College, Cuttack, Odisha, India. All cases were thoroughly examined

along with complete history. Blood was collected for routine hemogram, Liver function test (LFT) and

Prothrombin time (PT), -fetoprotein level, estimation of hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C virus

antibody. Totally 142 adult patients (>18 years) were enrolled in this study. Most common cause of portal

hypertension in our study was cirrhosis of liver (49%) followed by cirrhosis + Hepatocellular Ca (HCC) (15%),

Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis (NCPF) (13%), Budd-Chiary syndrome (BCS) (7%) and Extra Hepatic Portal Vein

Obstruction (EHPVO) (7%). Similarly anemia (85%) was the most common presentation followed by

splenomegaly (62%), haematemesis (62%) and malena (56%). Hepatic encephalopathy was present in 31%

of cases. Cirrhosis of liver followed by alcohol, hepatitis B or HCV infection was the commonest cause of

portal hypertension in elderly patients. Anemia followed by splenomegaly, haematemesis and melena are the

common presenting features of portal hypertension.

Keywords: Portal hypertension, cirrhosis, Budd-Chiary syndrome, anemia, splenomegaly, haematemesis.

Introduction

Portal hypertension (PH) is a common clinical syndrome

defined as the elevation of hepatic venous pressure

gradient 5 mm Hg (Groszmann et al., 2005). It can be

present as esophageal variceal bleeding, ascitis or

hypersplenism. But it is important to understand the

cause of portal hypertension to put in place the strategies

to prevent/ameliorate the same. PH can be due to many

different causes at prehepatic, intrahepatic and

posthepatic sites. Proper diagnosis and management of

these are vital for improving quality of life and patients

survival (Merli et al., 2003). The cause of portal

hypertension in every country varies. With increasing

affluence, better standards of living as well as change to

more sedentary life style in India, metabolic syndrome

leading to non-alcohol related fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

as well as alcohol related cirrhosis are expected to

increase in the coming years while hepatitis B or C virus

related cirrhosis may be expected to decline (Goel et al.,

2013). Only few studies were done in India which

focused on the cause of portal hypertension (Ray et al.,

2000; Verghese et al., 2007). Ray et al. (2000) reported

Hepatitis B as the more important cause of portal

hypertension in adults in eastern India. Studies from

other part of world reported Hepatitis C and alcohol as

the predominant etiology of chronic liver disease

(Mendez-Sanchez et al., 2004; Michitaka et al., 2010).

Various clinical presentations are direct consequences of

portal hypertension.

Youth Education and Research Trust (YERT)

In other complications, portal hypertension plays a key

role, although it is not the only factor for its development

(Kaji et al., 2012). Considering all the above facts, this

study was conducted to document the etiology of adult

patients of portal hypertension and evaluate their clinical

presentations.

Materials and methods

Patients: The study enrolled 142 cases of portal

hypertension patients admitted to the Dept. of general

medicine and hepatology unit, SCB Medical College,

Cuttack, Odisha, India. Cases were selected on clinical

ground and based on different related biochemical and

radiological investigations along with upper GI

endoscopy and histological liver biopsy in selected

cases. Patients with septicemia, ischemic heart disease

and other comorbid conditions like uncontrolled diabetes

were excluded from the study.

Experimental investigation: All cases were thoroughly

examined along with complete history. Blood was

collected for routine hemogram, LFT and PT,

-fetoprotein level, estimation of hepatitis B surface

antigen and hepatitis C virus antibody. Along with these

biochemical and cytological investigations of ascetic

fluid, test for fecal occult blood, routine and microscopic

examinations of urine, ECG, chest X-ray, USG of

abdomen, Doppler USG, endoscopy and CT scan of

abdomen were done.

jairjp.com

Jadumani et al., 2014

Journal of Academia and Industrial Research (JAIR)

Volume 3, Issue 5 October 2014

216

Liver biopsy was done in selected cases, where space

occupying lesions were detected by USG.

Results

There was a male preponderance with M:F ratio of 3:1.

Majority of cases belonged to 35-45 years and oldest

was of 70 years. Most were from lower socio-economic

status which may be due to high prevalence of

alcoholism in this group. Past history of patients revealed

that majority of them were addicted to alcohol (31%),

22% had suffered from viral hepatitis and 20% had

hematemesis (Table 1). Although past history of viral

hepatitis was obtained in only 56 patients (31%), HBsAg

was positive in 66 patients (47%), out of which 50 were

cirrhosis and 16 having HCC (Table 2). Anti-HCV

antibody was positive in 26 patients (18%), out of which

20 were having cirrhosis and 6 were having HCC.

All cases of Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis (NCPF),

Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) and

Budd-Chiari syndrome (BCS) were HBV and HCV

negative. Out of 16 selected patients who underwent

liver biopsy, all were having cirrhosis and sinusoidal

fibrosis and 12 patients were having features of HCC

(75%) (Table 3). In this study, AFP level was found to be

elevated in 22 patients with HCC (Table 4). The cause of

portal hypertension in the study included mainly cirrhosis

of liver, HCC, Non-cirrotic portal fibrosis, extrahepatic

portal vein obstruction and Budd-Chiary syndrome

(Table 5). Anemia (85%), splenomegaly (62%), melena

(56%), hematemesis (45%), swelling of abdomen (38%),

jaundice (31%) were most common clinical features of

the study (Table 6).

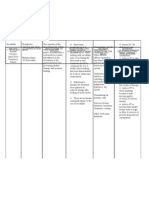

Table 1. Past history of patients.

Past history

History obtained

Alcoholism

56

Viral hepatitis

40

Haematemesis

36

Melena

24

Ascitis + Pedal oedema

26

Percentage

31%

22%

20%

13%

14%

Table 2. Prevalence of viral markers in patients.

No of

Status

cases

%

Disease

(n=71)

Cirrhosis

HBsAg +ve

66

47%

HCC

Anti-HCV

Cirrhosis

26

18%

antibody

HCC

NCPF

B -ve and

50

35%

EHPVO

C ve

BCS

Total

142

100%

No.

50

16

20

6

18

22

10

142

Table 3. Liver biopsy profile.

No of cases

Findings

Percentage

(n=16)

cirrhosis

16

100%

Sinusoidal fibrosis

16

100%

Features of HCC

12

75%

Youth Education and Research Trust (YERT)

Table 4. -fetoprotein (AFP) level in patients with HCC.

Level (mg/L)

No. of cases (n=22)

Percentage

< 500

0

0%

500-1000

2

9%

1000-1500

14

64%

>1500

6

27%

Total

22

100%

Table 5. Etiology of portal hypertension.

No. of

Cause

cases

Percentage

(n=142)

Cirrhosis of liver

70

49%

Cirrhosis +HCC

22

15%

Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis

18

13%

Extrahepatic portal vein obstruction

22

15%

Budd-Chiari syndrome

10

7%

Total

142

100%

Table 6. Symptoms and signs of PH at presentation.

No. of

Symptoms and signs

cases

Percentage

(n=142)

Hematemesis

88

62%

Ascitis (swelling of abdomen)

56

38%

Melena

80

56%

Loss of appetite

40

28%

Swelling of feet

30

21%

Anemia

120

85%

Engorged abdominal vein

20

14

Hepatomegaly

30

21%

Splenomegaly

88

62%

Jaundice

44

31%

Fever

20

14%

Hepatic encephalopathy

44

31%

Discussion

Portal hypertension is the most challenging health

problem of people all over the world. It is a widely

prevalent condition affecting people in their most

precious years of live (5-45 years). A vast majority of

literatures on portal hypertension have been published

from western countries where etiology and outcome

differ significantly from that of tropics. Paucity of

data in tropics compounds the doctors difficulties in

management of portal hypertension. Many workers hold

the view that chronic alcohol intake is a potent

predisposing factor for development of cirrhosis

of liver (Bellentani et al., 1997; Corrao et al., 1998).

Other workers also have noted past history of infective

hepatitis as high as >20% of cases of cirrhosis patients

(Rodger et al., 2000; Joseph et al., 2006). Past history of

hematemesis was found in 20% of patients and melena

was found in 13% of cases. Lebrec et al. (1980) found

almost similar incidence of upper GI bleeding in case of

cirrhosis (Lebrec et al., 1980). Liver biopsy done in

16 patients showed cirrhosis and sinusoidal fibrosis in all

patients and features of HCC were found in 75%.

jairjp.com

Jadumani et al., 2014

Journal of Academia and Industrial Research (JAIR)

Volume 3, Issue 5 October 2014

217

On studying the AFP level, 22 patients were found to be

having high levels of AFP. In an adult, high level of AFP

without an obvious GI tumor strongly suggest HCC.

Rising level suggest progression of tumor or recurrence

after hepatic resection. After studying all the Tables,

commonest etiology of portal hypertension was found to

be cirrhosis of liver followed by alcohol (n=56) or

followed by hepatitis B (N=66) or HCV infection (n=16).

Other etiologies were found to be extra hepatic portal

vein obstruction (n=22), hepatocellular carcinoma (n=22),

non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis (n=18) and Budd-Chiary

syndrome (n=10). This report is in variance from the

study conducted in Southern India (Goel et al., 2013)

where cryptogenic chronic liver disease was found to be

the predominant cause of portal hypertension followed by

alcohol and hepatitis B related liver disease. But our

study report is similar to other studies (Michitaka et al.,

2010; Johnson et al., 2011), where alcohol and hepatitis

C were found to be the main cause of PH. Alcohol intake

in India is steadily increasing with decrease in the

initiation age. This alarming trend is noticed in many

areas of country (Das et al., 2006). In our study, alcohol

intake was a significant contributory factor and this may

be a reflection of referral bias, low socio-economic

situation or can be a reflection of changing trend. On

focusing the clinical presentation of portal hypertensive

patients of our study, we found anemia in almost 85% of

cases, splenomegaly in 62% of cases. According to

different studies, anemia of diverse etiology occurs in

about 75% of patients with chronic liver disease

(McHutchison et al., 2006). A major cause of it is

hemorrhage into GI tract and defect in blood coagulation

in severe hepatocellular disease (Gonzalez-Casas et al.,

2009). Similarly Sherlock (1997) stated that if there is

no splenomegaly in a case of PH, the diagnosis is

erroneous. There are many studies to justify the

coexistence of splenomegaly with PH (Bolognesi et al.,

2002; Voros et al., 2005). Clinically the spleen might

have been shrunken due to acute GI bleed. However, the

other general symptoms like hematemesis, melena,

swelling of abdomen, pedal edema were observed in our

study during the time of presentation.

Conclusion

Most common cause of portal hypertension in our study

was cirrhosis of liver (49%) followed by cirrhosis + HCC

(15%), Non-cirrhotic portal fibrosis (13%), Budd-Chiary

syndrome and EHPVO. Similarly, we conclude from our

study that anemia is the most common presentation

followed by splenomegaly, haematemesis and melena.

However, further studies are needed taking a larger

study population regarding etiology of portal

hypertension in adults and in elderly from different parts

of India, especially to analyze variations in different

socio-economic categories. Overall, portal hypertension

is largely a preventable condition because the

commonest etiology is alcoholism.

Youth Education and Research Trust (YERT)

References

1. Bellentani, S., Saccoccio, G., Costa, G., Tiribelli, C., Manenti, F.,

Sodde, M., Saveria Croce, L., Sasso, F., Pozzato, G. and

Cristianini, G. 1997. Brandi and the Dionysos study group. Drinking

habits as cofactors of risk for alcohol induced liver damage. Gut.

41: 845-850.

2. Bolognesi, M., Merkel, C., Sacerdoti, D., Nava, V. and Gatta, A.

2002. Role of spleen enlargement in cirrhosis with portal

hypertension. Digest. Liver Dis. 34(2): 144-150.

3. Corrao, G., Bagnardi, V., Zambon, A. and Torchio, P. 1998.

Meta-analysis of alcohol intake in relation to risk of liver cirrhosis.

Alcohol Alcoholism. 33(4): 381-392.

4. Das, S.K., Balakrishnan, V. and Vasudevan, D.M. 2006. Alcohol: Its

health and social impact in India. Natl. Med. J. Ind. 19: 94-99.

5. Goel, A., Madhu, K., Zachariah, U., Sajith, K.G., Ramachandran, J.,

Ramakrishna, B., Gibikote, S., Jude, J., Chandy, G.M. and Elias, E.

2013. A study of etiology of portal hypertension in adults (including

the elderly) at a tertiary centre in southern India. Ind.

J. Med. Res. 137: 922-927.

6. Gonzalez-Casas, E., Jones, A. and Moreno-Otero, R. 2009.

Spectrum of anemia associated with chronic liver disease. World J.

Gastroenterol. 15(37): 4653-4658.

7. Groszmann, R.J., Garcia-Tsao, G. and Bosch, J. 2005.

Beta-blockers to prevent gastroesophageal varices in patients with

cirrhosis. New Engl. J. Med. 353(21): 2254-2261.

8. Johnson, E.A., Spier, B.J., Leff, J.A., Lucey, M.R. and Said, A.

2011. Optimising the care of patients with cirrhosis and

gastrointestinal haemorrhage: A quality improvement study.

Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 34: 76-82.

9. Kaji, B.C., Bhavsar, Y.R., Patel, N., Garg, A., Kevadiya, H. and

Mansuri, Z. A study of clinical profile of 50 patients with portal

hypertension and to evaluate role of non-invasive predictor of

esophageal varices. Ind. J. Clin. Pract. 22(9): 454-457.

10. Lebrec, D., Nouel, O., Corbic, M. and Benhamou, J.P. 1980.

Propranolol-A medical treatment for portal hypertension?

Lancet. 2(8187): 180-182.

11. McHutchison, J.G., Manns, M.P. and Longo, D.L. 2006. Definition

and management of anemia in patients infected with hepatitis C

virus. Liver Int. 26: 389-398.

12. Mendez-Sanchez, N., Aguilar-Ramirez, J.R., Reyes, A., Dehesa,

M., Juorez, A. and Castneda, B. 2004. Groupo de Estudio,

Asociaon Mexicana de Hepatologyia. Etiology of liver cirrhosis in

Mexico. Ann. Hepatol. 3: 30-33.

13. Merli, M., Nicolini, G. and Angeloni, S. 2003. Incidence and natural

history of small esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. J. Hepatol.

38(3): 266-272.

14. Michitaka, K., Nishiguchi, S., Aoyagi, Y., Hiasa, Y., Tokumoto, Y.

and Onji, M. 2010. Japan etiology of liver cirrhosis study group.

Etiology of liver cirrhosis in Japan: A nationwide survey.

J. Gastroenterol. 45: 86-94.

15. Perz, J.F., Armstrong, G.L., Farrington, L.A., Hutin, Y.J.H. and Bell,

B.P. 2006. The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C

virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide.

J. Hepatol. 45: 529-538.

16. Ray, G., Ghoshal, U.C., Banerjee, P.K., Pal, B.B., Dhar, K. and Pal,

A.K. 2000. Aetiological spectrum of chronic liver disease in eastern

India. Trop. Gastroenterol. 21: 60-62.

17. Rodger, A.J., Roberts, S., Lanigan, A., Bowden, S. And Crofts, N.

2000. Assessment of long-term outcomes of community-acquired

hepatitis C infection in a cohort with sera stored from 19711975.

Hepatol. 32: 582-587.

th

18. Sherlock, S. 1997. Disease of liver and billiary system, 9 edn.,

Blackwell Scientific Publications.

19. Verghese, J., Navaneethan, U. and Venkatraman, J. 2007. Clinical

pattern of elderly cirrhosis: An Indian experience. Eur. J.

Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 19: 1031-1033.

20. Voros, D., Mallas, E., Antoniou, A., Kafantari, E., Kokoris, S.E.,

Smyrniotis, B. and Pangalis, G.A. 2005. Splenomegaly and left

sided portal hypertension. Ann. Gastroenterol. 18(3): 341-345.

jairjp.com

Jadumani et al., 2014

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Algorithm GERD Primary Care Pathway Ahs SCN DH 2020 15262Документ7 страницAlgorithm GERD Primary Care Pathway Ahs SCN DH 2020 15262Mihaela ShimanОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Table e - Liver Anatomy Biliary SystemДокумент11 страницTable e - Liver Anatomy Biliary Systemapi-371971600Оценок пока нет

- PancreatitisДокумент6 страницPancreatitisMary AmaliaОценок пока нет

- Nursing Upper Gi BleedingДокумент23 страницыNursing Upper Gi BleedingLord Pozak Miller100% (3)

- Seminar: Pere Ginès, Aleksander Krag, Juan G Abraldes, Elsa Solà, Núria Fabrellas, Patrick S KamathДокумент18 страницSeminar: Pere Ginès, Aleksander Krag, Juan G Abraldes, Elsa Solà, Núria Fabrellas, Patrick S KamathcastillojessОценок пока нет

- Assessment and Management of Patients With Biliary DisordersДокумент16 страницAssessment and Management of Patients With Biliary DisordersJills JohnyОценок пока нет

- 461 706 1 PBДокумент6 страниц461 706 1 PBNulul Ci LoolyОценок пока нет

- Management of Portal Hypertension in Children: Ahmed Mahmoud El-Tawil, MSC, MRCS, PHDДокумент9 страницManagement of Portal Hypertension in Children: Ahmed Mahmoud El-Tawil, MSC, MRCS, PHDNulul Ci LoolyОценок пока нет

- Hypertension, Diuretic Use, and Risk of Hearing LossДокумент7 страницHypertension, Diuretic Use, and Risk of Hearing LossNulul Ci LoolyОценок пока нет

- Urinary Tract Infection in WomenДокумент11 страницUrinary Tract Infection in WomenDermovi Adika RangkutiОценок пока нет

- Leaflet SF68 Opportunity For New Territories 2009 Cerbios Probiotic CapsulesДокумент3 страницыLeaflet SF68 Opportunity For New Territories 2009 Cerbios Probiotic Capsulesamin138irОценок пока нет

- Abdominal Pain in ChildrenДокумент36 страницAbdominal Pain in ChildrenKiani LarasОценок пока нет

- პანკრეასიДокумент24 страницыპანკრეასიSASIDHARОценок пока нет

- Key Points SurgeryДокумент2 страницыKey Points SurgeryVyom ShrigodОценок пока нет

- 2-醫學四-住院病歷寫作範本 - 原則 增修版Документ6 страниц2-醫學四-住院病歷寫作範本 - 原則 增修版蘇西瓦Оценок пока нет

- Recent Advances in The Understanding of Bile Acid MalabsorptionДокумент15 страницRecent Advances in The Understanding of Bile Acid Malabsorptionbdalcin5512Оценок пока нет

- Perspectives in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology: A Gastroenterologist's Guide To ProbioticsДокумент9 страницPerspectives in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology: A Gastroenterologist's Guide To ProbioticsMihajilo TosicОценок пока нет

- Kokate List of Probiotics ApprovedДокумент3 страницыKokate List of Probiotics ApprovedHari ThekkethilОценок пока нет

- 2014 ProsidingSNIJAДокумент17 страниц2014 ProsidingSNIJASayu Putu Yuni ParyatiОценок пока нет

- Irritable Bowel SyndromeДокумент2 страницыIrritable Bowel SyndromeDeepthiОценок пока нет

- STUDIES ON ANTIULCER ACTIVITY OF Solanum Melongena (SOLANACEAE)Документ5 страницSTUDIES ON ANTIULCER ACTIVITY OF Solanum Melongena (SOLANACEAE)xiuhtlaltzinОценок пока нет

- 169166461003186341.1.2.virechan Patient ReferenceДокумент3 страницы169166461003186341.1.2.virechan Patient ReferenceBharathi PОценок пока нет

- Screenshot 2022-01-02 at 12.40.18 PMДокумент22 страницыScreenshot 2022-01-02 at 12.40.18 PMالقناة الرسمية للشيخ عادل ريانОценок пока нет

- Diarrhea - ChuДокумент19 страницDiarrhea - Chukint manlangitОценок пока нет

- EVH Cholangitis Cholangiohepatitis Syndrome 2019 220519 WebДокумент7 страницEVH Cholangitis Cholangiohepatitis Syndrome 2019 220519 WebLeo OoОценок пока нет

- Epigastric Pain and Indigestion CausesДокумент6 страницEpigastric Pain and Indigestion CausesNadia SalwaniОценок пока нет

- A Review of Crohn's Disease: Pathophysiology, Genetics, Immunology, Environmental Factors, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, ManagementДокумент18 страницA Review of Crohn's Disease: Pathophysiology, Genetics, Immunology, Environmental Factors, Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, ManagementValentina RodriguezОценок пока нет

- Reviewer Digestive SystemДокумент12 страницReviewer Digestive SystemLorenzo Gabriel RSОценок пока нет

- Drug Study CHDCДокумент1 страницаDrug Study CHDCIannBlancoОценок пока нет

- Digestive-SystemДокумент93 страницыDigestive-SystemJulia Stefanel PerezОценок пока нет

- Organic DiseasesДокумент3 страницыOrganic DiseasesGlenn Cabance LelinaОценок пока нет

- CON 1B GI and Endocrine DisordersДокумент2 страницыCON 1B GI and Endocrine DisordersAllyza Trixia Joyce VillasotoОценок пока нет

- 1 PBДокумент7 страниц1 PBIka Wirya WirawantiОценок пока нет

- Hepatology Research - 2023 - Yoshiji - Management of Cirrhotic Ascites Seven Step Treatment Protocol Based On The JapaneseДокумент12 страницHepatology Research - 2023 - Yoshiji - Management of Cirrhotic Ascites Seven Step Treatment Protocol Based On The JapaneseSarah FaziraОценок пока нет