Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Heinrich Ruling On Venue Evidence Unlawful Search

Загружено:

Sara PelisseroОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Heinrich Ruling On Venue Evidence Unlawful Search

Загружено:

Sara PelisseroАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

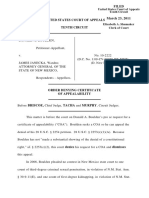

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 1 of 53

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

DISTRICT OF MINNESOTA

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Court File No. 15-cr-340 (JRT/LIB) (1)

Plaintiff,

v.

REPORT AND RECOMMENDATION

Danny James Heinrich,

Defendant.

This matter comes before the undersigned United States Magistrate Judge upon

Defendant Danny James Heinrichs (Defendant) Motion to Suppress Fruits of Unlawful Search

and Seizure, [Docket No. 34]; Motion to Suppress Statements, [Docket No. 37]; and Motion for

Change of Venue, [Docket No. 43]. This case has been referred to the undersigned Magistrate

Judge for a report and recommendation, in accordance with 28 U.S.C. 636(b)(1) and Local

Rule 72.1. The Court held a motions hearing on April 27, 2016, regarding the parties pretrial

motions.1

Following the motions hearing, the parties requested the opportunity to submit

supplemental briefing which was completed on June 1, 2016, and Defendants Motion to

Suppress Fruits of Unlawful Search and Seizure, [Docket No. 34]; Motion to Suppress

Statements, [Docket No. 37]; and Motion for Change of Venue, [Docket No. 43], were then

taken under advisement by the undersigned on June 1, 2016.

For reasons discussed herein, the Court recommends that Defendants Motion to

Suppress Fruits of Unlawful Search and Seizure, [Docket No. 34]; and Motion to Suppress

The Court addressed the parties pretrial discovery motions by separate order. [Docket No. 47].

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 2 of 53

Statements, [Docket No. 37] be DENIED. The Court also recommends that Defendants Motion

for Change of Venue, [Docket No. 43], be DENIED without prejudice.

I.

BACKGROUND2

Defendant is charged with ten counts of possession of child pornography printed

material, in violation of 18 U.S.C. 2252A(a)(5)(B), 2252A(b)(2), and 2256(8)(A); five counts

of possession of child pornography victim under twelve printed material, in violation of 18

U.S.C. 2252A(5)(b), 2252A(b)(2), and 2256(8)(A); one count of possession of child

pornography morphed image printed material, in violation of 18 U.S.C. 2252A(5)(b),

2252A(b)(2), and 2256(8)(C); one count of receipt of child pornography printed material, in

violation of 18 U.S.C. 2252A(a)(2)(A); 2252A(b)(1); and 2256(8)(A); one count of

possession of child pornography digital material, in violation of 18 U.S.C. 2252A(a)(5)(B),

2252A(b)(2), and 2256(8)(A); seven counts of receipt of child pornography digital material, in

violation of 18 U.S.C. 2252A(a)(2)(A), 2252A(b)(1), and 2256(8)(A); and one count of

possession of child pornography victim under twelve printed material, in violation of 18

U.S.C. 2252A(a)(5)(B), 2252A(b)(2), and 2256(8)(A). (Indictment [Docket No. 18]).

II.

DEFENDANTS MOTION TO SUPPRESS FRUITS OF UNLAWFUL SEARCH

AND SEIZURE. [DOCKET NO. 34].

Defendant moves the Court to suppress the images of child pornography forming the

basis of the charges now against him, as well as, any other evidence that was also gathered as a

result of the execution on July 28, 2015, of the state court warrant that authorized officers to

The Court has set forth the facts that are relevant to each motion in the section addressing each motion.

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 3 of 53

search his residence at 55 Myrtle Avenue South in Annandale, Minnesota (Defendants 2015

Residence), and to seize a buccal swab of Defendants DNA.3

A. Relevant Facts

On July 27, 2015, Investigator Dennis Kern (Investigator Kern) of the Wright County

Sheriffs Department, supervised by Stearns County Sheriffs Department Captain Pamela

Jensen, prepared an affidavit (the Kern Affidavit) in support of an application for a state court

warrant to search the Defendants 2015 Residence.4 (See, gen., Govt. Ex 8, Application 1-4 to 111; April 27, 2016, Motions Hearing, Digital Recording, at 10:40:25 a.m.). In the Affidavit,

Investigator Kern averred as follows:

Between 1986 and 1988, a series of incidents was reported as having occurred in

Paynesville, Minnesota, in which juvenile males were physically or sexually assaulted. (Govt. Ex

8, Application 1-4).

In August 1986, an unidentified white male, who was described as approximately 59

and husky with a mud-like substance on his face, struck a juvenile male and groped the font of

the juveniles pants before fleeing the scene. (Id.).

3

As drafted, Defendants motion asks the Court to suppress only evidence gathered as a result of the execution of

the state court search warrant for his house that also authorized the collection of a buccal swab sample of

Defendants DNA. (See Def.s Motion to Suppress Fruits of Unlawful Search and Seizure, [Docket No. 34]).

Similarly, Defendants motion papers refer only to the state court warrant to search his residence. (See, gen., Def.s

Memorandum in Support of Motion, [Docket No. 52]). However, at the motions hearing, the Government referred

to a second state court search warrant that authorized the installation of a tracking device on Defendants vehicle.

(April 27, 2016, Motions Hearing, Digital Recording at 10:28:08 a m.). The Government represented, and the

Defendant did not dispute, that the parties had met and conferred and had agreed that, because the affidavits in

support of the applications for both warrants were identical, the Government would submit only the affidavit in

support of the state court search warrant for Defendants residence for the Courts consideration. (Id.). Because the

Defendant has not, in the first instance, moved the Court to suppress any evidence gathered as a result of the state

court warrant that authorized the placement of a tracker on Defendants vehicle or offered any argument that the

placement was somehow unlawful, the Court concludes that the only state court search warrant at issue in the

present motion is the one that authorized the search of Defendants residence and the seizure of a buccal swab

sample of Defendants DNA.

4

The search warrant indicates that it was signed on July 24, 2015. (Govt. Ex. 8, Warrant 1-3). At the motions

hearing, the Government clarified, and Defendant did not dispute, that the search warrant was actually signed on

July 27, 2015. (April 27, 2016, Motion Hearing, Digital Transcript at 11:17:00 a.m.).

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 4 of 53

On August 21, 1986, an unidentified male, who was described as heavy set, between 56

and 58 tall, and wearing a long sleeve sweater and gloves, knocked a juvenile male to the

ground and groped the front of the juveniles pants, before fleeing the scene when a second

juvenile male approached. (Id.).

On November 30, 1986, an unidentified male, who was described as heavyset, having a

low, static filled voice, smelling strongly of cigarettes, and wearing a nylon windbreaker,

grabbed and dragged a juvenile male into some trees, where the unidentified male threatened to

kill the juvenile if he didnt remain silent. (Id.). The unidentified male rubbed the juveniles

testicles, then removed the juveniles stocking cap and cut off some of the juveniles hair using a

ragged edged knife. (Id.). The unidentified male then asked the juvenile his name and age,

threatened the juvenile again, and he left the scene still in possession of the juveniles stocking

cap and hair. (Id.).

On February 14, 1987, an unidentified male, who was described as heavy, approximately

56 tall, speaking in a low, deep whisper, and wearing a dark-colored quilted jacket with a mask

over his face, grabbed a juvenile male and threw him down some steps before threatening to kill

the juvenile if he did not remain silent. (Id.). The unidentified male groped the juveniles penis

and testicles, asked the juvenile what grade he was in, and threatened the juvenile with death if

he moved. (Id.). The unidentified male then left the scene with the juveniles wallet. (Id.).

On May 17, 1987, an unidentified male, who was described as pudgy, about 56 tall,

with a dark looking face and dark colored clothing, grabbed the same juvenile male who had

been groped during the February 14, 1987, incident, and threw the juvenile to the ground. (Id.).

The suspect fled the scene, leaving behind a baseball cap, when the juvenile began to scream.

(Id.).

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 5 of 53

On September 20, 1987, an unidentified male, who was described as chubby, between

57 and 58 tall, with short legs and with either a painted face or a facemask, approached two

juvenile males but fled when the juveniles screamed and ran. (Id. at 1-5).

In late summer of 1988, an unidentified white male, who was described as husky, with a

raspy voice, and was wearing pantyhose over his head, camouflage colored pants, a green army

type jacket, black boots, and black gloves, tackled one of two juveniles who were walking

together. (Id.) The unidentified male sat on the tackled juvenile, held a small knife to the

juveniles throat, and he threatened to kill the juvenile if the juvenile did not stop screaming.

(Id.). The juvenile fought back against the unidentified male and eventually the juvenile escaped

without being groped or harmed. (Id.).

In late fall of 1988, an unidentified white male, who was described as husky,

approximately 56 tall, and wearing a ski mask, a dark colored stocking hat, a black shirt, black

pants, and black gloves, knocked a juvenile male off of his bicycle before fleeing the scene on

foot. (Id.).

Investigator Kern stated that Defendant lived in Paynesville at the time of the aboveidentified incidents and that the incidents all occurred within several blocks of Defendants then

residence. (Id.). No arrests were ever made with regard to the above-listed incidents. (Id. at 1-7).

On January 13, 1989, at approximately 9:45 p.m., JNS, who was at the time twelve years

old, was kidnapped and sexually assaulted by an unidentified adult male. (Id.). JNS reported to

police that he had been grabbed by an adult white male and forced into the backseat of a car

approximately three blocks from his home in Cold Spring, Minnesota. (Id.).5 JNS told the police

that the adult male told JNS that he had a gun, and he instructed JNS to cover his face and lay

5

Cold Spring, Minnesota, is approximately 18 miles from Paynesville, Minnesota. Fed. R. Evid. 201(b).

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 6 of 53

down in the back seat. (Id.). JNS reported to police that he had noticed that the unidentified male

had a scratched, duct taped, handheld radio walkie talkie type device on the backseat, from

which JNS could hear voices coming until the driver turned the device off. (Id.). JNS reported to

police that he believed that he had been driven out of Cold Spring to a gravel road, where the

adult male stopped the car and then got into the backseat with JNS. (Id.).

JNS reported to the police that, after being ordered to do so by the unidentified adult male

driver, he had removed his snowsuit and pulled down his pants and underwear. (Id.). JNS

reported that the unidentified adult male had lowered his own pants, then he touched JNS penis

with his hand and ordered JNS to touch his penis, to which JNS complied. (Id.). JNS reported

that the driver then took JNSs penis into his mouth and ordered JNS to take the adult males

penis into his mouth, to which JNS complied. (Id.). JNS later reported to police that he had

wiped his mouth on his sweatshirt several times during the incident. (Id.). JNS reported that the

driver then unsuccessfully attempted to engage in anal sex with him before he returned to the

front seat of the car, which JNS described as a dark blue, new-smelling, four-door automatic

transmission passenger car with a luggage rack on the trunk, a center console shifter, a blue cloth

interior with dark blue leather or vinyl trim, and front bucket seats. (Id. at 1-6).

JNS reported that the adult male took and kept JNSs pants and underwear, but gave

JNSs snowsuit back to him and he allowed JNS to dress himself in it. (Id.). The adult male

drove JNS back to near Cold Spring, where he ordered JNS to exit the vehicle and to roll around

in the snow in his snow suit. (Id.). The adult male then ordered JNS to run away and he

threatened to shoot JNS if he looked back. (Id.).

JNS described the adult male as white with a darker complexion, in his mid-thirties,

approximately 56 to 57 tall, approximately 170 lbs., with dark brown mid-length hair, brown

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 7 of 53

eyes, fat ears that stuck out, a fat nose, bushy eyebrows, rough wrinkled skin, a broad neck, thick

shoulders, rough thick hands, a pudgy beer belly stomach, crooked bottom teeth, an

indentation of a ring on his right ring finger, and a deep raspy voice. (Id.). According to JNS, the

unidentified male wore a brown baseball cap with unknown lettering on it, a dark colored zip up

vest, camouflage fatigues, black Army boots, and a military style watch. (Id.).

Investigator Kern stated that, based on his review of documents and photographs from

that time period, Defendants physical description during the late 1980s was: white male, 55,

160 lbs., with brown hair and brown eyes. (Id.).

On January 16, 1989, a Stearns County Sheriffs Office Deputy identified Defendant as a

possible suspect in the kidnapping and sexual assault of JNS. (Id.). The deputy reported that

Defendant was driving a 1987 dark blue four-door Mercury Topaz that had a light blue interior

and bore Minnesota license plate #086CEZ. (Id.).6 The deputy also reported that Defendant was

at that time currently in either the National Guard or Army Reserve and had been seen wearing

military fatigues on a regular basis. (Id.).

On January 17, 1989, JNS was shown a photographic lineup of six photographs of males

with similar builds and characteristics. (Id.). Upon viewing the photographic lineup, JNS

identified two of the men in the photos, including Defendant, as somewhat resembling the

unidentified male who had kidnapped and sexually assaulted him. (Id.). Also on that date, a

Stearns County Sheriffs Office detective confirmed that Defendant was at that time a member of

the National Guard in the Willmar, Minnesota, area. (Id.).

On January 18, 1989, two Stearns County Sheriffs Office detectives observed a 1987 dark blue four-door Mercury

Topaz bearing Minnesota license plate # 086CEZ at Defendants then place of employment. (Id.). The detectives

observed that the vehicle did not have a luggage rack on it and that the interior of the vehicle appeared to be a light

gray. (Id.).

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 8 of 53

On October 22, 1989, at approximately 9:15 p.m. in the area of 29748 91st Avenue of St.

Joseph Township, which is located in Stearns County, Minnesota, a masked unidentified adult

male armed with a silver handgun approached three juveniles, identified in the Kern Affidavit as

TW, AL, and Jacob Wetterling. (Id. at 1-6, 1-7). The unidentified male ordered the juveniles into

a ditch, asked the juveniles their ages, and then grabbed ALs penis. (Id. at 1-7). The unidentified

male then ordered TW and AL to run away, and he threatened to shoot them if they looked back.

(Id.). The unidentified male then walked away from the scene with Jacob Wetterling, who has

not been seen since. (Id.). The unidentified male was described as between 59 and 510 tall,

approximately 180 lbs., with a low rough voice, and wearing a smooth nylon-type mask over his

face, a dark coat, dark pants, and dark shoes. (Id.)

TW and AL reported that they had not seen any vehicles parked near where the incident

occurred. (Id.). However, investigating officers later found both shoe and tire impressions in a

gravel driveway at 29748 91st Avenue in St. Joseph, approximately seventy-five (75) yards away

from the scene of the abduction. (Id.). The officers took cast impressions of the tire and shoe

impressions. (Id.). Investigator Kern stated that one of the shoe impressions looked similar to the

shoes that Jacob Wetterling had been wearing when he was abducted. (Id.).

On December 13, 1989, JNS worked with agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

(FBI) to create an artists rendering of his abductor. (Id.).

On December 16, 1989, two FBI agents interviewed Defendant. (Id.). Defendant told the

agents that he belonged to an Army National Guard unit in Willmar, Minnesota; that he only

wore camouflage clothing or Army boots while he was on guard duty; that he could not recall

where he had been on either January 13, 1989, or October 22, 1989; that, prior to February,

1989, he alternated between living at his fathers residence and his mothers residence, both of

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 9 of 53

which were in Paynesville; that between February 1989 and November 1989, he had lived at his

mothers residence; and that he moved to live at his fathers residence in November 1989. (Id.).

Defendant also told the agents that he had been driving a 1975 gray Ford Grenada until July

1989, when he sold the vehicle, and that he had begun driving a light or medium blue 1982 Ford

EXP in June of 1989. (Id.). Defendant denied having any knowledge of the abductions of JNS or

Jacob Wetterling. (Id.).

On January 8, 1990, Paynesville Police Chief Robert Schmiginsky informed the officers

investigating the Wetterling abduction about a number of reported incidents that had occurred in

Paynesville beginning in 1986, including the eight incidents listed above, in which an

unidentified adult male chased or groped juvenile males. (Id.). Chief Schmiginsky told the

investigating officers that he believed that Defendant should have been considered as a suspect in

the incidents. (Id.).

On January 12, 1990, law enforcement officers interviewed Defendant again. (Id.).

Defendant voluntarily provided his tennis shoes and some body hair samples to law enforcement.

(Id. 1-7, 1-9). Defendant also voluntarily authorized law enforcement officers to remove the rear

tires from his Ford EXP. (Id. at 1-7).

On January 15, 1990, a Stearns County detective reviewed documentation indicating that

Defendant had purchased a blue, four-door, automatic transmission 1987Mercury Topaz with a

blue interior on March 10, 1988, that was later repossessed from Defendant on March 10, 1989.

(Id. at 7). The Stearns County detective contacted the then current owner of the Mercury Topaz

who drove the car to the detective the next day. (Id.). On January 16, 1990, JNS sat inside the

Mercury Topaz to examine the vehicle. (Id. at 1-8). JNS said that the Mercury Topaz was highly

similar to, and felt like, the vehicle in which he had been kidnapped and sexually assaulted.

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 10 of 53

(Id.). Law enforcement took samples from the Mercury Topazs back seat carpet and back seat.

(Id.).

On January 24, 1990, the Stearns County Sheriffs Office executed a state court search

warrant for the residence of Defendants father, with whom Defendant was living at that time.

(Id.). The executing officers seized two radio scanners with operating manuals and lists of

scanner frequencies, a pair of black lace up boots, two brown caps, a camouflage shirt, a pair of

camouflage trousers, a vest, and some financial documents with Defendants name on them.

(Id.). Defendant produced six photographs to the officers while one of his locked trunks was

being searched. (Id.). One photo depicted a male child coming out of a shower with a towel

wrapped around him. (Id.). A second photo depicted a male child in his underwear. (Id.). A third

photo depicted three fully clothed children. (Id.). The last three photos were school type photos

of children with the last name Wurm. (Id.). Defendant told the officers that the photos were of

children from the Twin Cities area that he had met while he was a patient at the Willmar

Regional Treatment Center. (Id.). Law enforcement later confirmed that Defendant had been a

patient at that treatment facility. (Id.).

Officers interviewed Defendant while the state court search warrant for his fathers

residence was being executed. (Id.). Defendant told the officers during the interview that he had

been unemployed from October 8, 1989, until November 12, 1989; that he had not been in St.

Joseph on the weekend which included October 22, 1989; and that he could not recall where he

had been on October 22, 1989. (Id.).

On January 26, 1990, Defendant voluntarily appeared in a physical lineup that included

six individuals. (Id.). JNS was shown the lineup but could not positively identify any of the

individuals in the lineup as his abductor. (Id.). However, JNS identified Defendant and another

10

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 11 of 53

man as similar to his abductor in the build of their chests and stomachs. (Id.). JNS rated

Defendant as a four on a one-to-ten scale of similarity to his kidnapper, and the other man as a

seven. (Id.).

Also on January 26, 1990, the FBI Laboratory informed the officers investigating the

Wetterling abduction that the tires from Defendant Ford EXP were consistent with, but not an

exact match for, the tire impressions recovered from near the scene of the abduction. (Id. at 1-9).

On February 5, 1990, an FBI agent interviewed a James Wurm. (Id.). Wurm told the

agent that he had a sister who lived in Paynesville; that he and his wife had five boys ranging in

age from twenty-two to eleven; that two of his sons would often stay at his sisters residence in

Paynesville; and that he recalled a Tommy Heinrich playing football with his boys there. (Id.).

The agent showed Wurm a photograph of Defendant. (Id.). Wurm told the agent that Defendant

would often accompany Tommy Heinrich to his sisters residence but would not play football

with his boys; that his sisters residence had been burglarized five or six years earlier and had

also been burglarized and set on fire in November 1989. (Id.). Wurm also provided the agent

with pictures of his sons that had often stayed at his sisters residence, which the agent noted

looked similar to the photographs Defendant had produced during the execution of the state court

search warrant for his fathers residence. (Id.).

On February 9, 1990, Defendant was arrested in relation to the kidnapping and sexual

assault of JNS, but was later released without being charged. (Id.).

On March 5, 1990, the FBI Laboratory provided a report indicating that synthetic fibers

found on JNSs snowsuit exhibited the same microscopic characteristics and optical properties as

the fibers in the sample taken from the seat of the Mercury Topaz. (Id. at 1-8).

11

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 12 of 53

On April 13, 1990, the FBI Laboratory produced a report indicating that a shoe print

taken near the scene of the Wetterling abduction corresponded in design with Defendants right

shoe but, due to lack of sufficient detail, it could not be determined whether the impression at the

scene had been made by Defendants right shoe. (Id. 1-9). The report also indicated that the tread

pattern from the tires of Defendants Ford EXP was consistent with the tire impression taken

near the scene of the Wetterling abduction. (Id.).

On July 18, 2012, a Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension (MNBCA) report

indicated for the first time that a DNA profile had been obtained from JNSs snowsuit,

sweatshirt, and shirt. (Id.). DNA profiling results indicated that the samples taken from the right

wrist, neck, and chest of the sweatshirt, as well as, the center chest of the snowsuit, contained a

mixture of DNA from two or more individuals. (Id.). The profiling results indicated that JNS

could not be excluded as a contributor from the samples, but that 99.5% of the general

population could be excluded from being contributors. (Id.). The profiling results indicated that

the predominant male DNA profile from the right wrist of the sweatshirt did not, however, match

JNS. (Id.).

On March 5, 2014, a MNBCA lab report indicated that DNA profiling of a sample taken

from the baseball hat collected following the May 17, 1987, Paynesville incident, indicated that a

mixture of three of more unknown individuals was present in the sample. (Id.).

On July 10, 2015, Investigator Kern received a report indicating that recent MNBCA

testing of the hair samples Defendant had previously provided in 1990 indicated that the

predominant male DNA profile in the mixed sample taken from the right wrist of JNSs

sweatshirt was a match for Defendant, as well as, that the predominant profile could not be

expected to occur more than once among unrelated individuals in the world population. (Id. 1-9

12

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 13 of 53

to 1-10). The report also indicated that approximately 80.5% of the general population, but not

Defendant, could be excluded from the mixed sample taken from the baseball cap that had been

collected from one of the sexual assault scenes in Paynesville in 1987. (Id. at 1-10).

Investigator Kern stated in his affidavit that, based on his training and experience and the

knowledge and experience of other law enforcement officers involved in this investigation and

the investigation of other crimes against children, he was aware that serial sexual offenders who

engage in sexual fantasies may keep articles from their victims for years after the crime has been

committed; that the articles often consist of biological samples or clothing; and that some

offenders may also keep written or digital records in which they describe their fantasies or

crimes in detail. (Id.).

Investigator Kern further stated in his affidavit that, based on his training and experience

and the knowledge and experience of other officers in this investigation and other investigations

of crimes against children, he was aware that individuals who are sexually attracted to children

may collect and save sexually-explicit materials; that computers are often used to collect or

traffic in child pornography; that child pornographers and individuals with a sexual attraction to

children typically possess and retain for long periods of time sexually explicit materials in

various forms, as well as, correspondence relating to child pornography and an interest in

children; that child pornographers and individuals with a sexual interest in children rarely

voluntarily dispose of their sexually-explicit materials; and that individuals who share child

pornography are often individuals who have a sexual interest in children. (Id. at 1-10).

Investigator Kern also stated in his affidavit that, based on his training and experience

and the knowledge and experience of other officers in this investigation and other investigations

of crimes against children, that there are characteristics common to individuals involved in the

13

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 14 of 53

receipt and collection of child pornography including: the possible receiving of sexual

gratification, stimulation, or satisfaction from contact with children, from fantasies they may

have when viewing children involved in sexual activity or sexually suggestive poses in person or

in images or literature; the possible collecting of sexually explicit materials in various forms for

their own arousal or to use when attempting to seduce a child partner; the frequent possession

and retention over many years of various forms of digital and non-digital copies of their

sexually-explicit materials; the possible correspondence with others who shared similar interests;

and a preference to not be without their sexually explicit materials for long periods. (Id. at 1-10

to 1-11).

Investigator Kern attached to the Kern Affidavit now at issue copies of: the FBIs artist

rendering of the individual who had kidnapped and sexually assaulted JNS; a photograph of

Defendant taken in 1990; photographs from the interior of Defendants 1987 Mercury Topaz;

photographs of Defendants 1982 Ford EXP; photographs of the Defendants Ford EXPs tires;

photographs of the castings made and the footprints from the scene of the Wetterling Abduction;

photographs of Defendants shoes and the shoe prints from the scene of the Wetterling

abduction; the affidavit in support of the application for the state court warrant to search

Defendants fathers house in January 1990; the state court warrant authorizing the search of

Defendants fathers house in January 1990; and the search warrant return from the execution of

the state court warrant authorizing the search of Defendants fathers house in January 1990. (Id.

at 1-12 to 1-27).

On July 27, 2015, the Honorable Geoffrey W. Tenney, District Court Judge, Wright

County, Tenth Judicial District of the State of Minnesota, reviewed Investigator Kerns affidavit

and application for a state court warrant to search Defendants 2015 Residence. (See Govt. Ex. 8,

14

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 15 of 53

Warrant 1-3). Judge Tenney then issued a state court warrant authorizing a search of the

Defendants 2015 Residence, and the collection of a buccal swab sample of Defendants DNA.

(Id.).

When executing the state court search warrant, law enforcement officers collected a

buccal swab sample of Defendants DNA and they also seized a box, several photo albums,

nineteen three ring binders, and a computer containing the images of child pornography that

form the basis for the charges for which Defendant has been indicted in the present case, as well

as, a number of other items. (Govt. Ex. 8, Receipt, Inventory, and Return, 1-1, 3-2; see also

Indictment, [Docket No. 18], 1-2). The officers did not, however, seize anything that has been

connected to the Paynesville incidents, the kidnapping and sexual assault of JNS, or the

Wetterling abduction. (See Govt. Ex. 8, Receipt, Inventory, and Return, 1-1, 3-2).

B. Standard of Review

The Fourth Amendment guarantees the right of the people to be secure in their persons,

houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, and that no warrants

shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation. U.S. Const. Amend. IV.

The Eighth Circuit has held that [a]n affidavit establishes probable cause for a warrant if it sets

forth sufficient facts to establish that there is a fair probability that contraband or evidence of

criminal activity will be found in the particular place to be searched. United States v.

Mutschelknaus, 592 F.3d 826, 828 (8th Cir. 2010) (internal quotation marks and citation

omitted). Probable cause is a fluid concept that focuses on the factual and practical

considerations of everyday life on which reasonable and prudent men, not legal technicians,

act. United States v. Colbert, 605 F.3d 573, 576 (8th Cir. 2010) (quoting Illinois v. Gates, 462

U.S. 213, 231 (1983)). Courts use a totality of the circumstances test . . . to determine whether

15

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 16 of 53

probable cause exists. United States v. Hager, 710 F.3d 830, 836 (8th Cir. 2013) (citation

omitted).

The sufficiency of a search warrant affidavit is examined using common sense and not a

hypertechnical approach. United States v. Grant, 490 F.3d 627, 632 (8th Cir. 2007) (citation and

internal quotations omitted). In ruling on a motion to suppress, probable cause is determined

based on the information before the issuing judicial officer. United States v. Smith, 581 F.3d

692, 694 (8th Cir. 2009) (quoting United States v. Reivich, 793 F.2d 957, 959 (8th Cir. 1986)).

Therefore, [w]hen the [issuing judge] relied solely upon the supporting affidavit to issue the

warrant, only that information which is found in the four corners of the affidavit may be

considered in determining the existence of probable cause. United States v. Wiley, No. 09-cr239 (JRT/FLN), 2009 WL 5033956, at *2 (D. Minn. Dec. 15, 2009) (Tunheim, J.) (quoting

United States v. Solomon, 432 F.3d 824, 827 (8th Cir. 2005); edits in Wiley). In addition, the

issuing courts determination of probable cause should be paid great deference by reviewing

courts, Gates, 462 U.S. at 236 (quoting Spinelli v. United States, 393 U.S. 410, 419 (1969)).

[T]he duty of a reviewing court is simply to ensure that the issuing court] had a substantial

basis for . . . [concluding] that probable cause existed. Id. at 238-39 (quoting Jones v. United

States, 362 U.S. 257, 271 (1960)).

B.

Analysis

Defendant contends that the Kern affidavit did not provide sufficient probable cause for

the state court warrant to search his then residence in 2015, arguing that the information

contained in the Kern Affidavit was stale and, in any event, the information contained in the

Kern Affidavit did not establish a nexus to his then 2015 residence.

16

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 17 of 53

Defendant further argues that the Kern Affidavit was so lacking in indicia of probable

cause that the officers executing the search warrant could not rely in good faith on Judge

Tenneys determination that probable cause existed.

1. Sufficiency of the Affidavit

In the present case, the Kern Affidavit focuses on two primary bases to establish probable

cause to search Defendants 2015 Residence, namely: 1) child pornography; and 2) Defendants

connection to the Paynesville incidents and the JNS kidnapping and sexual assault.

a. Child Pornography

The evidence in the Kern Affidavit purporting to link Defendant to the possession of

child pornography consists only of the reference that, during the execution of the state court

warrant to search Defendants fathers residence in 1990, Defendant produced to the executing

officers a photograph of a child in his underwear, and a photograph of a child coming out of a

shower with a towel wrapped around him. The only information concerning those photographs in

the record presently before the Court consists of the above description and the fact that those

photographs were not seized by the officers investigating Defendant at that time in connection

with the Paynesville incidents and the kidnapping and sexual assault of JNS. There is no new

information since 1990 set forth in the Kern Affidavit which suggests possession or distribution

of child pornography. Moreover, the above information is not sufficient to convince the Court

that those earlier photographs from the 1990 search actually constituted child pornography in and

of themselves. However, when considered together with the totality of the other information in

the Kern Affidavit, as discussed in more detail below, there was information which could have

supplied Judge Tenney with a basis on which to conclude that Defendant had a possible interest

in children and that Defendant may have supported that interest with photographs of children.

17

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 18 of 53

Defendant argues that the evidence in the Kern Affidavit that Defendant has a sexual

interest in children and used photographs to support that interest referred to incidents that

occurred more than twenty-five years before the affidavit was drafted and, therefore, was too

stale to provide probable cause to believe that evidence of child pornography could be found at

Defendants 2015 Residence. If this were the sole basis for support relied upon by Judge Tenney

to issue the search warrant now at issue, the Court might agree.

Importantly probable cause must exist at the time of the search and not merely at some

earlier time. United States v. Gragg, 576 F. Appx 656, 658 (8th Cir. 2014) (quoting United

States v. Kennedy, 427 F.3d 1136, 1141 (8th Cir. 2005)). As such, a warrant will become stale

if the information supporting the warrant is not sufficiently close in time to the issuance of the

warrant and the subsequent search conducted so that probable cause can be said to exist as of the

time of the search. United States v. Brewer, 588 F.3d 1165, 1173 (8th Cir. 2009) (quoting

United States v. Palega, 556 F.3d 709, 715 (8th Cir. 2009)).

There is no fixed formula for determining when information has become stale. United

States v. Smith, 266 F.3d 902, 904-05 (8th Cir. 2001) (citing United States v. Koelling, 992 F.2d

817, 822 (8th Cir. 1993). The Eighth Circuit has explained that the vitality of probable cause

cannot be quantified by simply counting the number of days between the occurrence of the facts

supplied and the issuance of the affidavit[.] United States v. Tyler, 238 F.3d 1036, 1039 (8th

Cir. 2001) (citing Koelling, 992 F.2d at 822). Rather, [i]n determining whether probable cause

dissipated over time, a court must evaluate the nature of the criminal activity and the kind of

property for which authorization to search is sought. United States v. Tenerelli, 614 F.3d 764,

770 (8th Cir. 2010) (quoting United States v. Simpkins, 914 F.2d 1054, 1059 (8th Cir. 1990)). As

some courts have noted, [t]he observation of a half-smoked marijuana cigarette in an ashtray at

18

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 19 of 53

a cocktail party may well be stale the day after the cleaning lady has been in; the observation of

the burial of a corpse in a cellar may well not be stale three decades later. Tuzman v. State, 145

Ga. App. 761, 765, 244 S.E.2d 882, 886 (1978).7

The Courts independent research has not unearthed any case in which the information

giving rise to believe that images of child pornography could be found at a suspects residence

was deemed to still not be stale after the passage of a quarter-century.8 Further, there is no

indication in the Kern Affidavit that Defendant was, even in the 1990s, in possession of any

actual images of child pornography, nor any new information that Defendant, more recently,

used the internet to obtain or disseminate such images. In light of the particular circumstances in

this case, the information in Investigator Kerns affidavit in support of his application for the

state court search warrant was too stale to provide Judge Tenney with an independent basis to

conclude that evidence of child pornography could be found at Defendants 2015 Residence.

However, that does not end the Courts inquiry in regard to the 2015 search of Defendants then

Residence.

7

Courts have concluded that the nature of the crime of possession of child pornography, the electronic method of

storing such images, and the nature of the relationship that those who possess such images have with the images

warrant special consideration when determining how long probable cause may last to believe that such images may

be found at a suspects residence. See, e.g., United States v. Hyer, 498 F. Appx 658, 660 (8th Cir. 2013) (Given

the compulsive nature of the crime of possession of child pornography, information that might, in other

circumstances, be deemed stale can have substantial probative value.); United States v. Seiver, 692 F.3d 774, 777

(7th Cir. 2012) (noting that staleness is rarely relevant when the object to be found is a computer file); United States

v. Paull, 551 F.3d 516, 522 (6th Cir. 2009) [B]ecause the crime [of child pornography] is generally carried out in

the secrecy of the home and over a long period, the same time limitations that have been applied to more fleeting

crimes do not control the staleness inquiry for child pornography.). As a result, courts have concluded that probable

cause to search a suspects home for evidence of child pornography may persist for years after the evidence first

giving rise to the basis to believe that such images may be in the suspects home. See, e.g., United States v. Carroll,

750 F.3d 700, 707 (7th Cir. 2014) (victims statement that defendant had taken pornographic pictures of her as a

child five years previously was not too stale to support probable cause to search); Hyer, 498 F. Appx at 659

(information that defendant had admitted four years previously to possession images of child pornography was not

too stale to support probable cause).

8

The Court also notes that the electronic methods of maintaining child pornography that courts have recently cited

as a basis to conclude that possible child pornography warrants special consideration when determining the staleness

of probable cause were still relatively new in 1990, at the time that Defendant presented officers with the physical

photographs of the children that were identified in the Kern Affidavit.

19

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 20 of 53

b. Connection to previous incidents, abductions, and sexual assault

With regard to Defendants connection to the Paynesville incidents and the kidnapping

and sexual assault of JNS, the Kern Affidavit indicates that new DNA testing in 2014 and 2015,

of hair samples that Defendant had voluntarily provided in 1990, compared to DNA samples

taken from the clothing of JNS in 1990, had indicated that Defendants DNA was a statistical

match for the individual who had kidnapped and sexually assaulted JNS in January 1990. That

new information, when considered in context of the totality of the information which included

related to the events and investigations from 1989 and 1990, provided Judge Tenney with a basis

upon which to conclude that there was a fair probability to believe that Defendant kidnapped and

sexually assaulted JNS in 1989. In addition, there are a number of similarities between the

kidnapping and sexual assault of JNS and the earlier Paynesville incidents, including: the

geographical and temporal proximity of all of the incidents; that the perpetrators victims were

all juvenile males; that the perpetrator often groped the genitalia of his victims; the perpetrators

use of threats to get his victims to do his bidding; the consistent description of the perpetrator as

heavyset or husky; the common description of the perpetrators voice as low and rough; the

common description that the perpetrator attempted to cover his face; and the common description

that the perpetrator often wore dark clothing and gloves. As such, the new evidence in the Kern

Affidavit linking Defendant to the 1989 kidnapping and sexual assault of JNS, together with the

number and character of the similarities between that incident and the Paynesville incidents,

provided Judge Tenney with a basis to conclude that there was a fair probability that Defendant

was also the perpetrator of at least one the Paynesville incidents.

Further, the information in the Kern Affidavit indicates that the perpetrator of the

Paynesville incidents took hair and a stocking cap from one of the victims, and the perpetrator of

20

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 21 of 53

the kidnapping and assault of JNS also took articles of JNS clothing. The foregoing, together

with Investigator Kerns statements based on his training and experience that serial sexual

offenders are known to sometimes take biological materials and articles of clothing from their

victims and that they retain those items for years, provided Judge Tenney with some evidence to

conclude that there was a fair probability that Defendant had taken and kept items of clothing

and biological material from the Paynesville incidents and the JNS kidnapping and sexual

assault.

Defendant again argues that the fact that the above-identified incidents occurred two-anda-half decades before Judge Tenney issued the state court search warrant rendered the

information about those incidents too stale to provide probable cause in 2015 that Defendant still

possessed the items taken or that any evidence from those incidents could be now found at

Defendants 2015 Residence. 9

The Court notes that some of the same factors that might support a finding that probable

cause may continue to exist with respect to child pornography for many years are pertinent with

respect to the physical items taken from serial sexual assault victims. Investigator Kern stated in

9

At the motions hearing, Defendant spent a significant amount of time eliciting testimony regarding whether Captain

Jensen and the other investigating officers might have believed that the information in the Kern Affidavit concerning

the kidnapping and sexual assault of JNS and the Wetterling abduction might be stale as a result of the passing of the

statute of limitations. (See April 27, 2016, Motion Hearing, Digital Recording, at 11:21:40 a m.-11:22:30 a.m.; Id. at

11:42:00 a.m.-11:46:20 a.m.; Id. at 11:47:05 a.m.-11:49:20 a m.; Id. at 11:52:15 a.m.-12:01:35 a.m.). Courts of this

Circuit treat the statute of limitations as an affirmative defense. See, e.g., United States v. Soriano-Hernandez, 310

F.3d 1099, 1103 (8th Cir. 2002). The Court finds persuasive the reasoning of those courts that have directly

considered the issue that have concluded that a court deciding whether probable cause exists to issue a search

warrant is not required to consider the applicability of the statute of limitations or other affirmative defenses. See,

e.g., Kitch v. City of Kirkland, No. C11-823RAJ, 2012 WL 924345, at *9 (W.D. Wash. Mar. 19, 2012) (concluding

that no authority existed that required a judicial officer to consider the statute of limitations when issuing a search

warrant). The Court also finds persuasive the reasoning of those courts that have similarly held that an officer

executing a warrant is not required to independently determine the applicability of the statute of limitations. See,

e.g., Pickens v. Hollowell, 59 F.3d 1203, 1207-08 (11th Cir. 1995) (The existence of a statute of limitations bar is a

legal question that is appropriately evaluated by the district attorney or by a court after a prosecution is begun[.])

(Emphasis added).

21

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 22 of 53

his affidavit that based on his training and experience, as well as that of other involved

investigating officers, that serial sexual offenders may take and keep biological materials or

articles of clothing from their victims for years. The Kern Affidavit gave Judge Tenney a basis to

conclude that there was a fair probability that Defendant had taken articles of clothing from JNS,

and there is further information on which to conclude that there is a fair probability that

Defendant was also the perpetrator of at least one of the similar Paynesville incidents, in which

hair and clothing articles were taken and a baseball cap of the perpetrator in one of the incidents

resulted in new DNA test results which linked Defendant to the baseball cap. Further, unlike

images of child pornography, which are fungible in that that are easily obtained and disseminated

electronically, items taken from JNS and the victims of the Paynesville incidents are unique in

that they can come only from the perpetrators specific victims.10 As such, the passage of time is

of less importance in the present case and the Court concludes that the evidence in Investigator

Kerns affidavit in support of his application for the state court search warrant provided Judge

Tenney with a basis to believe that there was a fair probability that Defendant is linked to the

kidnapping and sexual assault of JNS and took items from him, when considered together with

the new 2014 and 2015 DNA testing result information contained in Investigator Kerns

affidavit, was not too stale to provide probable cause to search Defendants 2015 Residence or

collect a buccal swab sample of Defendants DNA.

10

With regards to the unique items from the Paynesville incidents and the JNS kidnapping and sexual assault, the

Court finds the reasoning of State v. Multaler, 643 N.W.2d 437 (April 25, 2002), at least informative. In Multaler,

the Supreme Court of Wisconsin rejected the argument that the information contained in an affidavit in support of a

search warrant application was too stale to provide probable cause to link the defendant to four homicides that had

occurred more than twenty years before the warrant issued; the focus in Multaler was a search for items taken from

the victims that might be found at the defendants residence. See, gen., Id. The affidavit in support of the application

for the state court search warrant in Multaler connected the victims to each other, and as in the present case, it

directly connected the defendant to some of the victims, and circumstantially connected the defendant to other

victims. Id. at 442-43. Also, as in this case, the affidavit in Multaler said that items had been taken from some of the

victims by the perpetrator. Id.

22

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 23 of 53

Defendant further contends that the information in the Kern Affidavit does not provide a

nexus to Defendants 2015 Residence, arguing that there was not sufficient evidence in the

affidavit to indicate that Defendant actually lived at 55 Myrtle Avenue, and that there was no

evidence linking evidence of the crime to the residence.

To establish a nexus between the crime at issue and probable cause to search the place

specified in the search warrant, an affidavit in support of search warrant application must set

forth only a fair probability that, given the circumstances set forth in the affidavit, contraband or

evidence of a crime will be found in a particular place. United States v. Tellez, 217 F.3d 547,

549 (8th Cir. 2000) (citations omitted).

Defendant first contends that there was a lack of evidence establishing that he actually

lived in the house at 55 Myrtle Avenue. The only indication in the Kern Affidavit that Defendant

lives at 55 Myrtle Avenue in Annandale, Minnesota, is Investigator Kerns single reference to

the house at that location as Defendants home. The Court notes that the affidavit at issue in

United States v. Colbert contained a similarly conclusory statement that the address to be

searched was the defendants home. See Colbert, 605 F.3d 573, 575 (8th Cir. 2010). Although

the Colbert court noted that the affidavit in that case was not a model of detailed police work[,]

the court concluded that the affidavit contained sufficient other specific facts and it rejected the

argument that the affidavit was too conclusory to establish probable cause. Id. at 576. The same

conclusion is warranted here.

Defendant next contends that there was nothing in the affidavit that directly indicated that

any evidence of the Paynesville incidents or the JNC kidnapping and sexual assault would be at

Defendants 2015 Residence. However, a court may draw reasonable inferences from the

circumstances when determining whether an affidavit in support of a search warrant application

23

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 24 of 53

establishes a nexus between the items to be found and the place to be searched. United States v.

Summage, 481 F.3d 1075, 1078 (8th Cir. 2007) (quoting United States v. Thompson, 210 F.3d

855, 860 (8th Cir. 2000)).

In the present case, the Court concludes that there was sufficient specific information

contained in the Kern Affidavit on which Judge Tenney could reasonably infer that there was a

fair probability Defendant would keep evidence of at least one of the Paynesville Incidents and

the kidnapping and sexual assault of JNS at his home. Numerous courts have found the inference

reasonable that a possessor of child pornography will keep images of such in his home due to the

private nature of the images and the need to keep the images in a secure place like the home. See,

e.g., United States v. McArthur, 573 F.3d 608, 613 (8th Cir. 2009). As discussed above, the

information in the Kern Affidavit pertaining to child pornography was too stale on its own as a

singular basis to provide probable cause to search Defendants 2015 Residence. However, many

of the characteristics of child pornography which make it reasonable to infer that a suspect would

keep such at their home also make it reasonable to infer that an alleged serial sex offender would

keep physical items taken from his victims at a secure, private place like his home. See United

States v. Cortes, No. CRIM. 12-293 ADM/JJG, 2013 WL 828866, at *3 (D. Minn. Mar. 6, 2013)

(noting that affidavit had identified items associated with sexual assault, including clothing, as

items typically kept in the home).11

Based on all of the foregoing, the Court concludes that Investigator Kerns affidavit in

support of the application for the state court search warrant provided Judge Tenney with a

substantial basis to reasonably conclude that a fair probability existed to believe that evidence

11

Probable cause to search a residence could be because it was the site of an alleged criminal act, but probable cause

to search a residence could also, independently be established because evidence of a crime might be found or kept

there even though the crime was not committed there. The two bases are not interdependent.

24

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 25 of 53

relating to the Paynesville incidents and the kidnapping and sexual assault of JNS could be found

at 55 Myrtle Avenue in 2015.

It must be noted that the Kern Affidavit did not provide probable cause to search

Defendants residence for images of child pornography, and such images constitute the primary

evidence that Defendant now seeks to suppress as they form the basis for the charges now

against him. However, because the Kern Affidavit established probable cause to search

Defendants 2015 Residence for evidence connected to the Paynesville incidents and the

kidnapping and sexual assault of JNS, those officers were still lawfully present in Defendants

home when executing the state court search warrant even if the officers ultimately did not find

any such evidence. It is well established that officers who are on a suspects premises when

executing a valid search warrant may lawfully seize contraband beyond that authorized by the

warrant, provided that the contraband is in plain view of the officer and the officer is in a

location where the officer was lawfully allowed to be. See, e.g., Horton v. California, 496 U.S.

128, 135 (1990). It is also well established that [a] lawful search extends to all areas and

containers in which the object of the search may be found. United States v. Hughes, 940 F.2d

1125, 1127 (8th Cir. 1991) (citations omitted). Because the officers were lawfully allowed to

search for evidence in Defendants 2015 Residence, that may be connected to the Paynesville

incidents and the kidnapping and sexual assault of JNS, the officers could search anywhere such

evidence could be found, and consequently, the officers were lawfully able to seize the images of

child pornography in their plain view while doing so. Horton, 496 U.S. at 135.

2. Good Faith

Assuming solely for the sake of argument and in the interest of completeness that

Investigator Kerns affidavit in support of the application for the search warrant at issue did not

25

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 26 of 53

provide Judge Tenney with a substantial basis to conclude that probable cause existed to search

Defendants 2015 Residence and seize a buccal swab sample of Defendants DNA, the court

concludes that the officers executing the search warrant did so in good faith reliance on Judge

Tenneys determination that probable cause existed. See, gen., United States v. Leon, 468 U.S.

897, 901 (1984).

Under the Leon good-faith exception, disputed evidence will be admitted if it was

objectively reasonable for the officer executing a search warrant to have relied in good faith on

the judges determination that there was probable cause to issue the warrant. Grant, 490 F.3d at

632 (citing Leon, 468 U.S. at 922).

There are four circumstances, however, in which the Leon good faith exception does not

apply:

(1) the magistrate judge issuing the warrant was misled by statements made by the

affiant that were false or made in reckless disregard for the truth; (2) the

issuing magistrate judge wholly abandoned his [or her] judicial role; (3) the

affidavit in support of the warrant is so lacking in indicia of probable cause as to

render official belief in its existence entirely unreasonable; or (4) the warrant is

so facially deficient ... that the executing officers cannot reasonably presume it to

be valid.

United States v. Marion, 238 F.3d 965, 969 (8th Cir. 2001) (quoting United States v. Taylor, 119

F.3d 625, 629 (8th Cir. 1997)). Defendant contends that the third situation applies to the

circumstances of the present case, arguing, as he has above, that the information in the Kern

Affidavit was too stale to provide probable cause and that it failed to establish a nexus between

the items to be found and Defendants residence. The Court disagrees for all of the reasons

discussed in section II.B.1.b., above.

The courts review above of the Kern Affidavit indicates that Investigator Kern provided

Judge Tenney with specific evidence from the lengthy investigation, including new DNA

26

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 27 of 53

evidence information from 2014 and 2015 linking Defendant to the kidnapping and assault of

JNS, and circumstantially linking Defendant to at least one of the Paynesville incidents. As

discussed above, and as noted in Investigator Kerns affidavit, there is a basis to believe that

serial sexual offenders will often retain physical items taken from their victims for long periods

of time. In addition, the officers were aware that the perpetrator of the above incidents had in fact

taken such items.

Accordingly, when executing the search warrant for Defendants residence, law

enforcement relied in good faith on the search warrant issued by Judge Tenney.

Based on all of the foregoing, the undersigned recommends DENYING Defendants

Motion to Suppress Fruits of Unlawful Search and Seizure, [Docket No. 34].12

III.

DEFENDANTS MOTION TO SUPPRESS STATEMENTS. [DOCKET NO. 37].

Defendants motion asks the Court to suppress statements that the Defendant made on

July 28, 2015, October 26, 2015, October 28, 2015, and October 29, 2015.13 At the motions

hearing, the Government stated that it did not intend to offer into evidence at trial the statements

that Defendant had made on October 28, 2015 and October 29, 2015. (April 27, 2016, Motion

Hearing, Digital Recording at 10:27:20 a.m.). At the hearing, the Court confirmed, therefore,

with the parties that the motion to suppress statements pertained only to the statements made on

July 28, 2015, and October 26, 2015. (Id. at 10:28:00 a.m.).

12

Because the undersigned concludes that the information provided in Investigator Kerns affidavit in support of his

application for the state court search warrant provided Judge Tenney with a substantial basis on which to conclude

that probable cause existed to search Defendants home and to seize a buccal swab sample of Defendants DNA,

and that, in any event, the officers executing the search warrant relied in good faith on Judge Tenneys

determination that probable cause existed for the state court search warrant to issue, the undersigned need not

address the Governments alternative argument that the evidence obtained during the execution of the search warrant

need not be suppressed because the officers would have inevitably discovered it.

13

At the motion hearing, the Court confirmed with the parties that the statement Defendant originally misidentified

in his moving papers as having been made on November 2, 2015, was in fact made on October 29, 2015. (April 27,

2016, Motion Hearing, Digital Recording at 10:26:45 a m.).

27

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 28 of 53

A. Relevant Facts

1. July 28, 2016

Shortly after 8:30 a.m. on July 28, 2015, Captain Jensen and MNBCA agent Ken

McDonald went to Buffalo Veneer and Plywood, in Buffalo, Minnesota, Defendants place of

employment, in an unmarked squad car to ask Defendant to either provide the officers with a key

to his residence or, in the alternative, to accompany the officers to the residence to unlock it to

allow the officers to enter it in order to execute the state court search warrant for Defendants

residence issued by Judge Tenney on July 27, 2016. (April 27, 2016, Motions Hearing, Digital

Recording at 10:42:55 a.m.; Id. at 10:43:20 a.m.; Id. at10:44:40 a.m.; Id. at 10:44:50 a.m.). The

officers hoped that Defendant might make statements during the encounter that would further

their investigation and they made an audio recording of the encounter using concealed recording

devices. (Id. at 10:43:30 a.m.).

Captain Jensen and Agent McDonald wore street clothes when they went to Defendants

place of employment. (Id. at 10:44:50 a.m.). The officers were armed but their duty weapons and

badges were beneath their jackets and not visible. (Id. at 10:44:55 a.m.). The building which

houses Buffalo Veneer and Plywood is structured so that the front part of the building contains

offices while the rear part of the building contains a production line. (Id. at 10:45:00 a.m.). Upon

entering, the officers identified themselves as members of law enforcement and asked one of the

business employees in the front office area if they could speak to Defendant. (Id. at 11:24:02

a.m.). The business employee paged Defendant, who came from the production line area to the

front office area to speak with the officers. (Id. at 10:46:00 a.m.).

The two officers were allowed to use one the front offices to speak to Defendant. (Id. at

10:52:10 a.m.). The officers were alone with Defendant in the office, which measured

28

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 29 of 53

approximately 8 by 10. (Id. at 10:52:20 a.m.; Id. at 11:24:29 a.m.). Captain Jensen shut the

door to the office, but there was a window between the office and the general area at the front of

the building. (Id. at 10:52:35 a.m.; Id. at 11:24:44 a.m.).

After Defendant entered the office, Captain Jensen introduced herself and identified

herself as a law enforcement officer. (Govt. Ex. 1 File Voice0003.MP3 at 3:10). She told

Defendant that the officers had a state court warrant to search Defendants residence, and she

asked Defendant to accompany the officers to unlock the house to allow them to execute the

warrant. (Id. at 3:25). At Defendants request, Captain Jensen provided Defendant with a copy of

the warrant. (Id. at 3:40). While Defendant was reviewing the search warrant, Captain Jensen

told him that he was not under arrest and he did not have to accompany the officers. (Id. at 3:59).

Agent McDonald told Defendant that the officers did not want to break into the residence and

had come to Defendant to ask him to provide a key to the residence. (Id. at 4:04). Defendant

ultimately agreed to go with the officers to open his residence. (Id. at 5:15). After Defendant had

reviewed the search warrant, Captain Jensen retrieved it. (April 27, 2016, Motions Hearing at

10:51:35 a.m.). The officers initial encounter with Defendant lasted approximately three

minutes. (See, gen., Govt. Ex. 1 File Voice0003.MP3).

The officers told Defendant that they would wait for him outside the building near where

he had parked his car. (Id. at 5:50). While Defendant went to his locker in the production area to

obtain his keys, the officers exited the business by the front door and went to sit in their car.

(April 27, 2016, Motion Hearing, Digital Recording at 10:54:48 a.m.). The officers then

followed Defendant as he drove his own vehicle to his residence. (Id. at 10:55:08 a.m.). The

officers remained in visual sight of Defendant at all times during the drive. (Id. at 11:26:11 a.m.).

29

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 30 of 53

The officers did not activate their emergency lights or sirens during the drive to Defendants

residence. (Id. at 10:56:05 a.m.).

Once Defendant and the officers arrived at Defendants 2015 Residence, Defendant

pulled his vehicle into the driveway while the officers parked their unmarked squad car on the

street in front of the house. (Id. at 10:56:23 a.m.). At the residence, the officers made both audio

and video recordings of their interactions with Defendant. (April 27, 2016, Motions Hearing,

Digital Recording at 10:44:15 a.m.). Defendant exited his vehicle and began walking towards the

residence with Captain Jensen and Agent McDonald following closely behind him. (Id. at

10:56:52 a.m.). As Defendant was going to open the door, Captain Jensen asked Defendant

whether he planned to stay until the officers finished executing the search warrant to lock the

house afterwards. (Govt. Ex. 1 File VOICE004.MP3 at 0:25). Defendant responded that he

planned to stay during the execution of the warrant. (Id. at 0:40). Captain Jensen indicated that

Defendant and the officers could sit and wait under a portable gazebo in Defendants backyard

while the search warrant was being executed. (Id. at 0:45). Defendant responded that he would

rather wait in the house during the execution of the warrant, (Id. at 0:50), but Captain Jensen told

Defendant that he could not wait in the house while the warrant was being executed. (Id. at 0:53).

Defendant asked the officers if he could enter the house to put his lunch container in the

refrigerator and the officers allowed him to do so. (Id. at 0:56). Captain Jensen, who wanted to

make sure that Defendant did not move anything before the state court search warrant was

executed or try to obtain something harmful to the officers, told Defendant that she needed to

enter the residence with him. (Id. at 1:03; April 27, 2016, Motion Hearing, Digital Recording at

10:57:20 a.m.; Id. at 10:58:20 a.m.). Defendant allowed both Captain Jensen and Agent

McDonald into the residence. (Id.).

30

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 31 of 53

Once the three were inside the residence, Captain Jensen asked Defendant to surrender

his cellular phone because it was listed as one of the items to be seized in the search warrant.

(Govt. Ex. 1 File VOICE004.MP3 at 1:10; April 27, 2016, Motions hearing, Digital Recording at

10:51:45 a.m.). After Defendant provided Captain Jensen with his cellular phone, Captain Jensen

told Defendant that if he needed to call anyone they could talk about it. (Govt. Ex. 1 File

VOICE004.MP3 at 1:50).14

Defendant put his lunch container in the refrigerator. (April 27, 2016, Motions hearing,

Digital Recording at 10:54:28 a.m.). Defendant then offered the officers a beverage, which they

declined. (Id. at 10:57:34 a.m.; Id. at 11:04:22 a.m.).

Captain Jensen suggested that Defendant get himself some beverages and snacks. (Govt.

Ex. 1 File VOICE004.MP3 at 1:40). Defendant then grabbed two containers of beer from the

refrigerator and carried them with him as Defendant, Captain Jensen, and Agent McDonald

exited the residence. (April 27, 2016, Motions hearing, Digital Recording at 10:57:37 a.m.; (Id.

at 11:04:30 a.m.).

Eight other officers from the Stearns County Sheriffs Office, the FBI, and the MNBCA,

who had been assigned to physically execute the state court search warrant for Defendants 2015

Residence delayed their arrival at the residence until Captain Jensen, Agent McDonald and

Defendant had arrived at the residence. (Id. at 10:59:29 a.m.; Id. at 11:27:25 a.m.). Captain

Jensen, Agent McDonald, and Defendant went to sit at the portable gazebo in Defendants

backyard.

(Id. at 10:59:22 a.m.). The other officers parked three or four unmarked law

enforcement vehicles around the residence. (Id. at 11:28:42 a.m.).

14

Captain Jensen later testified at the motions hearing that she was not attempting to restrict Defendants ability to

contact others by asking for Defendants cellular phone. (April 27, 2016, Motions hearing, Digital Recording at

10:51:55 a m.).

31

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 32 of 53

The execution of the search warrant took approximately five hours. (See Id. at 11:01:08

a.m.). During the entire time the other officers executed the search warrant, either Captain Jensen

or Agent McDonald or both waited with Defendant in his back yard, where they continued to

converse with him. (Id. at 11:01:22 a.m.). Captain Jensen later testified at the motions hearing

that she and Agent McDonald had removed their jackets at some point while the other officers

were executing the search warrant, such that Defendant might have seen their badge and service

weapons. (Id. at 11:29:22 a.m.). However, neither Captain Jensen nor Agent McDonald

brandished their weapons at any time during the encounter. (Id. at 11:46:30 a.m.).

Shortly after the three sat at the gazebo, Captain Jensen reminded Defendant that he was

not under arrest and he could leave whenever he wished. (Id. at Govt. Ex. 1 File VOICE004.MP3

at 3:17). The subsequent conversation that Defendant had with Captain Jensen and Agent

McDonald covered a very wide range of topics. (See, gen., Govt. Ex. 1 File VOICE004.MP3;

Govt. Ex. 1 File VOICE005.MP3; Govt. Ex. 1 VOICE006.MP3; Govt. Ex. 1 File

VOICE007.MP3; Govt. Ex. 1 VOICE008.MP3; Govt. Ex. 1 VOICE009.MP3; Govt. Ex. 1 File

VOICE010.MP3). For purposes of the present motion, the Court notes that its independent

review of the audio recording of the encounter indicates that Defendant and the two officers

engaged each other casually and in conversational tones throughout the five hours they waited

for the other officers to finish executing the search warrant. (See, gen., Govt. Ex. 1 File

VOICE004.MP3; Govt. Ex. 1 File VOICE005.MP3; Govt. Ex. 1 VOICE006.MP3; Govt. Ex. 1

File VOICE007.MP3; Govt. Ex. 1 VOICE008.MP3; Govt. Ex. 1 VOICE009.MP3; Govt. Ex. 1

File VOICE010.MP3).

While the other officers were executing the search warrant, Defendant consumed the two

beers that he had brought out of the house with him while the three waited at the gazebo. (April

32

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 33 of 53

27, 2016, Motions Hearing, Digital Recording at 11:04:33 a.m.). However, Defendant did not

appear to Captain Jensen at any time to have become intoxicated. (Id. at 11:04:50 a.m.).

Defendant appeared to Captain Jensen to understand the conversation that he was having with

the officers and he gave appropriate responses to the officers questions. (Id. at 11:05:05 a.m.)

Defendant also appeared to be attentive to the search warrant process. (Id. at 11:05:22

a.m.). At his request, Captain Jensen provided Defendant with a copy of the search warrant. (Id.

at 11:33:00 a.m.). Defendant could see the back door of the residence from where he sat with the

officers in the back yard, and he was able to observe as some of the officers physically executing

the warrant made multiple trips removing items from the residence through the back door. (Id. at

11:28:15 a.m.).

At one point during the execution of the search warrant, Defendant got up to urinate. (Id.

at 11:17:20 a.m.; See also Govt. Ex. 1, VOICE005.MP3 at 1:23:58-1:25:33; VOICE009.MP3 at

12:15-12:44). The officers did not prevent Defendant from doing so. (April 27, 2016, Motion

Hearing, Digital Recording at 11:17:30 a.m.). Nor did the officers accompany Defendant, who

went into the garage and urinated in a cat litter box. (Id. at 11:17:32 a.m.; 11:32:30 a.m., see also

Govt. Ex. 1, VOICE005.MP3 at 1:23:58-1:25:33; VOICE009.MP3 at 12:15-12:44).

Sometime between 10:46 a.m. and 11:00 a.m., Agent McDonald collected the DNA

buccal swab sample from Defendant as he switched out tobacco he had been chewing. (See

Govt. Ex. 2 at 00002075).

After the execution of the search warrant was complete, the officers conducting the

search removed a number of boxes containing items seized from Defendants residence when

they left the residence. (April 27, 2016, Motion Hearing, Digital Recording at 11:05:48 a.m.).

33

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 34 of 53

Captain Jensen and Agent McDonald thereafter also left the residence. (See Id. at 11:06:00 a.m.).

Defendant was not arrested on that date. (Id. at 10:44:35 a.m.; Id. at 11:05:52 a.m.).

Defendant was not subjected to a pat search of his person at any time on July 28, 2016.

(Id. at 10:59:10 a.m.). The officers did not at any time on July 28, 2016, read Defendant a

Miranda warning. (Id. at 11:35: 25 a.m.).

Between July 28, 2016, and October 26, 2016, law enforcement had examined the items

that had been seized from Defendants residence and determined that only some of the seized

items had any evidentiary value. (Id. at 11:06:45 a.m.). The officers decided that they would

return the items that they deemed to not possess evidentiary value to Defendant at his residence.

(Id. at 11:07:28 a.m.). The officers also hoped they might have an additional conversation with

Defendant when they returned the items. (Id. at 11:07:37 a.m.).

2. October 26, 2016

On October 26, 2015, Captain Jensen and Agent McDonald initiated a second encounter

with Defendant. (Id. at 11:0640 a.m.). Shortly after 4:00 p.m., a time when the two officers

believed that Defendant would be returning home from work, the officers, again dressed in plain

clothes, parked an unmarked squad car down the street from Defendants residence and waited

for him to arrive. (Id. at 11:10:34 a.m.; Id. at 11:10 50 a.m.; Id. at 11:35:58 a.m.). Captain Jensen

and Agent McDonald had with them some of the items to be returned and a van that was not yet

then at the residence carried the rest of the items. (Id. at 11:35:12 a.m.). The officers also brought

recording devices with them when they went to Defendants home to return the items, and they

again made an undisclosed audio recording of the encounter. (Id. at 11:08:25 a.m.). Once the

officers saw Defendant park his car in the driveway of his residence, the officers pulled up to the

curb in front of the residence. (Id. at 11:10:45 a.m.). The officers hailed Defendant and told him

34

CASE 0:15-cr-00340-JRT-LIB Document 56 Filed 06/21/16 Page 35 of 53

that they were there to return some of his property. (Id. at 11:11:05 a.m.). Captain Jensen later

testified at the motions hearing that she could not recall whether the officers badges or service

weapons were visible at that time. (Id. at 11:36:04 a.m.). However, neither Captain Jensen nor