Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Group Polarization Isenberg

Загружено:

Miha MajcenИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Group Polarization Isenberg

Загружено:

Miha MajcenАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Journal of Personally and Social Psycholog> 1986. Vol. 50. No. 6 .

' l l 4 l - I I S I

Copyright 1986 by the American Psychological Association. Inc. 0022-3 S14/86,'JOO.1'!

Group Polarization: A Critical Review and Meta-Analysis

Daniel J. Isenberg Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration

This article critically reviews recent (1974-1982) group polarization studies that address themselves to either one of the two primary explanatory mechanisms thought to underly group polarization, namely social comparison and persuasive argumentation processes. A summary of the effect sizes of 21 published articles (33 independent effects) suggests that social comparison and persuasive argumentation occur in combination to produce polarization, although the persuasive argumentation effects tend to be larger. Attempts are made to reconcile the two positions, and some suggestions for further research are offered.

In 1961 James Stoner observed that group decisions are riskier than the previous private decisions of the group's members (Stoner, 1961). Since that time several hundred studies have shown that (a) the ''risky shift" is a particularly pervasive phenomenon: (b) on certain decisions groups are more cautious than their members: and that (c) both risky and cautious shifts are special cases of a more general phenomenongroup-induced attitude polarization (Moscovici & Zavalloni. 1969; Myers & Lamm, 1976). Group polarization is said to occur when an initial tendency of individual group members toward a given direction is enhanced following group discussion. For example, a group of moderately profeminist women will be more strongly profeminist following group discussion (Myers. 1975). Thus, on decisions in which group members have, on the average, a moderate proclivity in a given direction, group discussion results in a more extreme average proclivity in the same direction. The group polarization literature is an encouraging example of how theoretically and practically meaningful phenomena in social psychology can be defined and explored through empirical research: 1. In recent years polarization research has been cumulative such that subsequent research studies have addressed the problems and issues identified by previous researchers. This has been amply demonstrated by several excellent literature reviews (Lamm & Myers, 1978; Myers, 1982; Myers & Lamm. 1976). 2. Researchers have pursued lines of programmatic research rather than one-shot experimental studies (e.g., Blascovich & associates: Myers & associates: Vinokur & Burnstein; Baron & associates). 3. Theoretical explanations of polarization phenomena have been disconfirmed (see Pruitt, 1971a. 1971b), thus focusing research on an increasingly small number of explanatory mechanisms. For example, in 1971 Pruitt identified 11 (overlapping) explanatory mechanisms for choice shifts, whereas by 1978 this list had been pruned and consolidated into 2 major ones, social

The author would like to thank Robert F. Bales. Roger Brown. David Myers, Reid Hastie, and anonymous reviewers for their help and suggestions at various stages of this research. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Daniel J. Isenberg, Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration, Soldiers Field Road. Boston, Massachusetts 02163.

comparison processes (Sanders & Baron. 1977), and persuasive argumentation (Burnstein & Vinokur, 1977). 4. Finally, the polarization literature has made a substantial contribution to social psychological theory. As one example, Brown (1974) and Myers (1982) both have noted that the group polarization literature is significant for its emphasis on a counterconformity effect because groups shift away from the average attitude in the group rather than toward it. Another review of the polarization literature would be redundant as several excellent reviews of the literature up to 1978 already exist (see Lamm & Myers, 1978; Myers, 1982; Myers & Lamm. 1975. 1976; see also Clark, 1971: Pruitt. 1971a, 1971b). The primary purpose of the present article is to critically reviewin particular the recent literature (especially 1974-1982) that addresses itself to the dialogue between proponents of social comparison and persuasive arguments as explanations of attitude polarization (Burnstein & Vinokur, 1977; Sanders & Baron, 1977). The mid-1970s serve as an appropriate point of departure because it was at this time that the debate concerning these two explanatory processes became highly salient. Furthermore, it was then that many researchers who had helped produce the hundreds of risky-shift studies began to veer away from further research in the field. At the time it appeared that the risky-shift was an interesting but limited and severely qualified phenomenon that had already outlived its theoretical usefulness (e.g., Cartwright, 1973; Kleinhans & Taylor, 1976). In very recent years enthusiasm for group polarization research has again begun to wane: it is hoped that an in-depth review will help reorient research in the field, in particular toward a third wave of research that will integrate group polarization with other social psychological and cognitive phenomena. This article will conclude by suggesting four areas of integration. In addition to reviewing this recent literature, attention will be paid to reporting the relative effect magnitudes of demonstrations of persuasive argument and social comparison mediating mechanisms. Social Comparison Introduction As far back as Brown's (1965) seminal discussion of the risky shift, one of the major explanations of choice shifts has been a

1141

1142

DANIEL J. ISENBERG

social comparison explanation. According to this perspective, people are constantly motivated both to perceive and to present themselves in a socially desirable light. In order to do this, an individual must be continually processing information about how other people present themselves, and adjusting his or her own self-presentation accordingly. Some versions of social comparison theory state that many of us desire to be perceived as more favorable than what we perceive to be the average tendency. Once we determine how most other people present themselves, we present ourselves in a somewhat more favorable light. When all members of an interacting group engage in the same comparing process, the result is an average shift in a direction of greater perceived social value. There are two variations of the above sequence, one emphasizing the removal of pluralistic ignorance, and the other emphasizing one-upmanship (bandwagon effects). According to the pluralistic ignorance explanation (see Levinger & Schneider, 1969; Pruitt. 197la; Schroeder. 1973: see also Isenberg, 1980), individuals present their own positions as compromises between two tendencies, the desire to be close to one's own ideal, and the desire not to be too deviant from the impression of the central tendency of the group. Prior to group discussion, group members initially underestimate the group norm and. judging from the initial ratings of their own positions, are somewhat distant from their ideal. During group discussion, individuals are exposed more nearly to the true group norm, and thus a discrepancy between how much better an individual is and would like to be becomes apparent. Upon making a second set of choices, the individual group members shift closer to their ideal positions. When this process takes place with most group members, an overall polarization is observed. The assumption underlying the pluralistic ignorance explanation of choice shifts is that pluralistic ignorance exists because of a lack of accurate communication about the "true" beliefs of the majority of group members, although it is also likely that pluralistic ignorance may be due to cognitive biases, such as self-other differentials in person perception (see Jones & Nisbett. 1972). Other investigators have hypothesized a second explanation for the effects of social comparison processes on polarization (e.g., Brown. 1974: Myers. 1978; Myers. Bruggink, Kersting, & Schlosser, 1980; Myers, Wojcicki, & Aardema. 1977). These and other investigators hypothesize that people are motivated by a desire to be different and distinct from other people in a valued direction (Fromkin, 1970). In addition, people are also motivated to present themselves somewhat more favorably than other people. In other words, w-e want to be different from as well as better than other people. Brown states, "To be virtuous . . . is to be different from the meanin the right direction and to the right degree" (1974, p. 469). When making initial ratings along a dimension, individuals give themselves a rating that is somewhat more favorable than the rating they presume the average group member will give. When individuals directly or indirectly infer what the true norm is, they then "improve" their own ratings, thus producing the overall choice shift. Whereas the mechanism producing choice shifts in the pluralistic ignorance explanation is a compromise between self-enhancement and conformity, the mechanism underlying bandwagon effects is a compromise be-

tween self-enhancement and humility. In reality, however, it may be very difficult to distinguish these two mechanisms empirically. There are several overlapping variations on the pluralistic ignorance and bandwagon effects, such as cultural values (Hong. 1978), release mechanisms (Pruitt, 197la, 197Ib), self-presentation processes (Jellison & Arkin. 1977), specific values (Stoner, 1968), and self-anchoring (implicit in Festinger, 1954; Brown, 1974).'

The Evidence

The major source of support for social comparison theory has come from demonstrations that simple knowledge about other group members' positions by itself can produce polarization effects. These effects are called "mere-exposure" effects, and we will use that terminology here. A number of studies have attempted to establish that mere exposure to central tendency information can be a sufficient cause of choice shifts (Baron & Roper. 1976: Blascovich & Ginsburg, 1974:Blascovich, Ginsburg. & Howe, 1975, 1976; Blascovich. Ginsburg, & Veach, 1975: Goethals&Zanna, 1979; Myers, 1978; Myers etal., 1980; Myers etal.. 1977: see also Pruitt's reviews, 1971a, 1971b). I shall review each study in some depth. Blascovich and associates. Blascovich and his associates should be noted for their persistence in pursuing mere-exposure effects, as well as for the fact that they use true risk-taking situations in their research. In one study (Blascovich, Ginsburg, & Veach, 1975), three experimental conditions were formed for blackjack playing. One was an individual condition, one was a group-without-discussion condition, and the third was a groupwith-discussion condition. Subjects were randomly assigned to experimental conditions and played 20 hands of blackjack alone in order to establish a baseline. Then each subject played 20 hands of blackjack in the experimental condition. In the groupwithout-discussion condition, subjects heard each others' bets but did not discuss them. In the group-with-discussion condition, subjects placed one collective bet after trying to reach a consensus. There were two relevant findings from the Blascovich, Ginsburg. and Veach (1975) study. First, the individual (no-group)

A word about the latter is in order because it has been implied by the literature but never explicitly stated. Festinger (1954) argued that one reason people seek out comparison information is in order to define social reality. For example, what it takes to be considered "intelligent" or "conservative" depends on an individual's comparison with how much of these qualities the average individual possesses. If the average IQ is 75. then an IQ of 90 is intelligent. If the majority of the people in a given population are against racial integration, then an individual favoring busing is considered very liberal, even if he or she is against interracial marriage. In other words, these qualities are socially defined. This aspect of social comparison theory is usually overlooked in explaining polarization. It is possible that the motivation underlying differentiation of the self from the presumed group norm is to maintain one's self-definition, not necessarily to enhance it. As Brown (1974) comments, "Giving advice in private, then, each participant means to be somewhat audacious. But how can he know how to be so since the situations are novel and invented?" Thus, information about the central tendency defines what response is virtuous, nonvirtuous, risky, or cautious. Social reality and the social self are defined only through information about other people.

GROUP POLARIZATION control did not increase the size of their bets between the first and second blocks of 20 hands, whereas both group conditions did show marked increases. r(14) = .44 and .37 for the withand without-discussion conditions, respectively.2 Second, neither group condition showed a greater polarization than the others from block one to block two. This finding was extended by Blascovich et al. (1976). r(\2) = .44. Blascovich. Ginsburg. and Veach (1975) and Blascovich et al. (1976) interpreted their studies as showing that norms of risk or caution emerge, driving either risk or caution upward only when the norm is observable by the individual. In agreement with Jellison and Arkin (1977), these authors suggested that group members associate ability and skill with riskiness (or caution) and thus become more risky (or more cautious) in order to appear more able and skillful (see also Blascovich & Ginsburg. 1974; Blascovich, Ginsburg, & Howe, 1975). Nevertheless, one potential weak spot in their argument is that in order to claim abilityattribution mediators they would have to explain why both shifts to risk and shifts to caution are found, and why either can be interpreted as ability under different circumstances. Baron and Roper. Experiments by Baron and Roper (1976) add support to the mere-exposure hypothesis and specifically attempt to show how the direction of social value predicts the direction of polarization. In Experiment 1, subjects participated in an autokinetic study in which they were assigned to one of three conditions, depending on whether they were told that perceiving smaller, larger, or better estimates of light movement was positively related to intelligence. Subjects in the three experimental conditions made their light estimates alone, for a 15-trial baseline, and then for an additional block of 15 trials as a group in which members simply called their estimates out loud so that other group members could hear. In a control condition, subjects were told that larger estimates were related to intelligence, but they made the second block of 15 estimates as individuals, without being exposed to others' estimates. The results of this first study were mixed. In the larger intelligence condition, subjects' estimates did polarize in the predicted direction (toward larger estimates), r(44) = .41, but they did not polarize in the other conditions. It appeared that there was an overall tendency for estimates to increase over blocks, but the authors did not report a block main effect. These findings were replicated and extended in subsequent experiments (Baron & Roper, 1976): /"(39) = .43. These studies are particularly interesting because the task that subjects performed was an argument-poor one, in other words, one in which it was difficult for subjects to generate novel and valid arguments either in favor of or against perceiving light motion (see Vinokur & Burnstein. 1978b). It appears that this is at least one example of a situation that one would find difficult to explain without assuming some purely value-determined comparison process (Sanders & Baron, I977). 3 Myers and associates. Another study (unpublished, reported in Myers, 1982) demonstrated that exposure to others' positions on argument-poor tasks can produce polarization. Dyads were shown slides of faces that had been judged previously as either attractive or unattractive. On each trial, one member of the dyad made a judgment of the attractiveness of the slides and announced the judgment out loud so that the other dyad member could hear. Then the second member of the dyad made his or her judg-

1143

ment. The prediction from the mere-exposure hypothesis was that for the attractive face, the second member's judgment should be more attractive than the first member's, and the reverse should be true for the unattractive face. In fact, there was a 1.75 to 1 tendency for the second member to polarize his or her judgments. As Myers argued, it is rather difficult to imagine that novel or valid arguments could be generated by the second member in order to rationalize the shift to a more extreme judgment. A recent series of studies by Myers and his associates have provided additional evidence for the mere-exposure hypothesis (Myers, 1978; Myers et al., 1980: Myers et al., 1977). In the first of these studies (Myers et al.. 1977) the authors contrasted pluralistic ignorance (Levinger & Schneider. 1969) and release theory (Pruitt. 1971a. 197 Ib) explanations of polarization by exposing subjects to the group average response or to extreme responses within the group. The awareness of group norms is assumed to be the mediating mechanism in pluralistic ignorance (Levinger & Schneider, 1969). Awareness of extremes, which presumably releases group members from the constraints of the perceived group norms, is the mediating mechanism in release theory (Pruitt. 197 la, 197 Ib). An attitude survey of 269 members of a church was conducted in two stages. In stage 1. 100 members rated their own agreement/disagreement with 16 church-related statements (e.g.. "Ministers should feel free to take a stand from the pulpit on some political issue."). Three weeks later the remaining members (169) either (a) responded to the statements in a control condition: (b) were given the average of the previous 100 members' responses and then responded to the 16 statements; or (c) were given a frequency distribution of the previous 100 members' responses and then responded to the 16 statements. Those subjects in the average-exposure and frequency-exposure condition showed significantly more extreme attitudes compared to the controls, ij = .23. r(265) = .17." The frequency-exposure condition showed more extreme attitudes than the pretest baseline as well. There were no differences between subjects in the average

- Throughout this article I recomputed the / and F statistics to the more universal measure of effect size, r, which is the Pearson productmoment correlation and therefore can be identically summed, averaged, and tested for significance. The formula for computing r from Ms r = t/ (l2 * df)1'2. For F(\. df), r = F/(F + <#')' 2 since t2 = F for degrees of freedom = 1. of/'(see Rosenthal. 1978). In several studies investigators inappropriately tested specific hspotheses with the omnibus F using greater than I dim the numerator. In each of these studies it was possible to test a specific hypothesis with I d f i n the numerator, thus allowing a more powerful test and allowing the computation of r. In all cases, an r greater than 0 indicates an effect in the predicted direction. Further details of these calculations are available from the author. 3 Nevertheless, it behooves the authors to explain within their framework why the smaller intelligence condition in Experiment 1 did not produce the predicted shift. 4 This is only an estimate of r because the exact cell means are not given in M\ers et al. (1977). but were estimated from the histogram presented in the article. Furthermore, the r reflects the effect size of the difference between the two exposure conditions and the two control conditions. Basically, it is the effect size of the F ratio for the comparison between exposure and nonexposure. The SS (between) was calculated from the estimated means, and given the F ratio from the article the SS (error) was calculated.

1144

DANIEL J. ISENBERG

and frequency-exposure conditions, thus giving an explanatory advantage to neither release nor pluralistic ignorance theories. The first of two studies by Myers (1978) replicated and extended the above findings by using eight Choice Dilemmas Questionnaire (CDQ)5 items, four risky and four cautious, and the eight traffic cases from Kaplan's (1977) study, four innocent and four guilty shifting cases. Exposure caused polarization for both the CDQ items. r(\02) = .27, and the traffic cases. r(!02)= .44. It is commendable that these studies pit theoretical predictions against one another. Nevertheless, it should be pointed out that the above comparisons between release and pluralistic ignorance explanations have two potential flaws. First, the manipulation is confounded with the amount of information: Subjects in the release conditions were exposed to a full frequency distribution, whereas subjects in the pluralistic ignorance condition were exposed to one number, an average. A second criticism is that differences between scores from release and pluralistic ignorance conditions may be attenuated by the low salience of the information (see Borgida & Nisbett, 1977). Whereas Myers found polarization effects for both conditions when subjects in both of those conditions were exposed to relatively abstract and unvivid information, exposure to more salient information about the norm or extremes (for example, via video tape) may actually lead to greater polarization for one or the other of the two conditions. The findings of Isenberg and Ennis (1981) can be interpreted as showing that deviant group members (i.e.. extremes) are in fact particularly salient in the minds of other group members.6 In a second experiment. Myers (1978) controlled for the effects of repeated measurements and had successive groups of subjects rate the same eight CDQ items after having been exposed to the actual ratings of the previous group. As predicted, polarization was greatest for the total of 60 subjects in the exposure conditions. r(\ 16) = .33. Subsequent studies by Myers et al. (1980) have replicated and extended their demonstration of mere-exposure effects. r(18) = .86" and r(21) = .43. Goet/ials and Zanna. Goethals and Zanna (1979) reported one relatively recent attempt to demonstrate that normative processes alone can produce polarization. Following reconceptualizations of Festinger's (1954) statement on social comparison theory (e.g.. Goethals & Darley. 1977; Jellison & Arkin. 1977: Jellison & Riskind. 1970). Goethals and Zanna argued that the mere-exposure hypothesis will onl\ be true when group members believe that they are similar to one another on attributes that are related to the judgments being made. Since risk taking and ability are perceived as related, group members who perceive themselves as similar in ability should polarize to greater risk following group discussion. "Social comparison theory implies that people will feel it is appropriate to take as much risk as others of equal ability but less risk than those who possess greater ability" (p. 1470). A total of 137 subjects responded individually to four CDQ items, rated themselves on overall "talent, creativity, and ability," and then were assigned to one of four conditions. In a group-discussion condition, groups of four subjects discussed the four CDQ items and then completed the items again in private. In an information-exchange condition, groups of subjects were exposed to each other's positions when each group member

held up a card showing his or her position (I will refer to this condition as the partial-exchange condition). An informationexchange-of-position-flw/-ability condition (which I will refer to as the full-exchange condition) was like the partial-exchange condition except that group members also shared their self-ratings of ability. (As expected, group members were similar in rating themselves as above average in ability). In a control condition, subjects simply rerated the CDQ items privately after reconsidering them for 10 min. Because the variances across conditions were heterogeneous, nonparametric statistics were used to compare the number of groups polarizing to risk in each condition. Overall, the amount of polarization varied quite substantially among conditions, x2 (3. -V = 32) = 10.42. p < .02, being greatest in the full-exchange condition. More specifically, both the groupdiscussion and the full-exchange conditions showed greater polarization to risk than did the partial-exchange condition (p < .05: my own reanalysis of the differences between the partialand full-exchange conditions showed x2 ( U -V = 16) = 6.35. p < .02. r( 14) = .63. After the experiment, group members rated the average group comember in terms of his or her overall talent, creativity, and ability, and it was found that indeed subjects in the full-exchange condition saw other group members as more similar than did subjects in the partial-exchange condition. The authors interpreted these findings in support of the mediating role of perceived similarity of abilities in producing polarization, although this interpretation raises two issues. First, what is the relation between risk taking and risk advocacy? The risk-ability link assumes that Person A will be a good comparison for risk taking for Person B if Person B perceives their risk-related abilities as similar. This was not the comparison performed by group members in the full-exchange condition, because risk taking was not an issue, only the advocacy of risk (cf. Blascovich & Ginsburg. 1978). Second, a different interpretation might suggest another mediating mechanism, namely that exposure to others' self-ratings enhanced source credibility: "I had better listen to all of these (self-proclaimed) talented people who are advocating more risk than I had expected them to."

Informational Influences Introduction

Much research has been devoted to studying how the processing of relevant information can affect group polarization (e.g..

The original risky-shift research bv Stoner (1961) used scenarios in which subjects read each scenario and then recommended how much risk thev thought the character in the scenario should take. Decision scenarios involved chess moves, career shifts, professional choices, and so forth. 6 A third qualification of the Myers studies is the possibilitv that release theory and pluralistic ignorance theory are in fact different, but the effect is so small as to be trivial. Both of Myers's studies showed frequencvexposure conditions to be slightlv more effective than average-exposure conditions in producing polarization, but the effects, simply and combined, were nonsignificant. " This is based on the comparison of the polarization in the three experimental conditions versus the controls. The omnibus f\'3. 18) = 3.73. and given the 4 cell means 55 (between) was calculated and the contrast performed.

5

GROUP POLARIZATION Anderson & Graesser, 1976; Bishop & Myers. 1974: Ebbesen & Bowers, 1974: Kaplan, 1977: Kaplan & Miller. 1977: Madsen. 1978: Vinokur & Burnstein, 1978a). The most sophisticated and well-researched version of the information processing explanation for choice shifts is persuasive arguments theory (PAT; e.g.. Burnstein & Vinokur. 1975. 1977; Burnstein, Vinokur, & Trope, 1973: Madsen. 1978; Vinokur & Burnstein. 1974. 1978a). PAT holds that an individual's choice or position on an issue is a function of the number and persuasiveness of pro and con arguments that that person recalls from memory when formulating his or her own position. Thus, in judging the guilt or innocence of a trial defendant, jurors come to predeliberation decisions on the basis of the relative number and persuasiveness of proguilt and proinnocence arguments. Group discussion will cause an individual to shift in a given direction to the extent that the discussion exposes that individual to persuasive arguments favoring that direction. Since the notion of persuasiveness is so central to PAT, some research has been devoted to ascertaining the characteristics of arguments that make them persuasive. Burnstein (1982; Vinokur & Burnstein. 1978b) persuasively argued that two factors determine how persuasive a given argument will be. One factor is the perceived validity of the argument. How true is the argument? Does the argument fit into the person's previous views? Does the argument logically follow from accepted facts or assumptions? The second factor determining persuasiveness is the perceived novelty of the argument. Does the argument represent a new way of organizing information? Does the argument suggest new ideas? Does the argument increase the perceiver's access to additional information that is stored in memory? For example, the argument. "Cigarette smoking is bad because it causes cancer in the smoker." is valid, but it is not novel anymore. The argument. "Cigarette smoking is bad because it causes cancer in nonsmokers who inhale the smoke when smokers are present." is relatively novel. To the extent that the two arguments are perceived as equally valid, the latter, more novel argument should be more persuasive. Together, the perceived validity and perceived novelty of an argument determine how influential that particular argument will be in causing a choice shift. The novelty-persuasiveness hypothesis has received experimental support (Vinokur & Burnstein. 1978b). PAT seriously qualifies the risky shift phenomenon by making shifts contingent upon the argument pool within the group. A given group may or may not shift in a given direction, depending upon the possession and expression of persuasive arguments during the group discussion. The role of novelty is particularly central. If arguments are presented that the individual group member is already aware of, a shift in his or her position will not occur as a result of the discussion (Kaplan. 1977). If novel persuasive arguments are presented that are opposite to the direction initially favored by the group member, their position will shift in the opposite direction and depolarize (Kaplan. 1977: Vinokur & Burnstein. 1978a). Thus, a juror who initially favors a guiltv verdict will come to favor a more guilty verdict if and only if he or she is exposed to novel persuasive arguments in favor of guilt. The specificity of the process by which PAT produces choice shifts lends it two major strengths as a theory: (a) given appro-

1145

priate information. PAT can predict the direction and extent of choice shifts, be they polarizing or depolarizing (Vinokur & Burnstein, 1978a). (b) PAT facilitates the conceptual integration of individual and group decision making, since the underlying mechanism is the same for arguments processed privately or in interaction with other people.

The Evidence

The evidence for the proposition that persuasive arguments alone can produce choice shifts and attitude polarization is quite strong and from the start has been one of the best-supported explanations of polarization phenomena (see Pruitt. 197la. 1971 b). However, the statement that only a persuasive argument mechanism mediates choice shifts (e.g.. Burnstein & Vinokur. 1977) is premature on empirical and theoretical grounds (see Sanders & Baron, 1977, and Burnstein & Vinokur, 1977. for a debate on this particular issue). I will summarize the major findings in support of PAT. emphasizing the most recent additions to the literature not covered in the reviews by Lamm and Myers (1978) and Myers and Lamm (1976). The evidence will be organized around three hypotheses: 1. There is a correlation between the extent of polarization and the prior preponderance of pro and con arguments that are available to group members (the correlational hypothesis). 2. Group polarization can be caused by manipulating the preponderance of pro and con arguments that are processed (the causal hypothesis). 3. PAT is a necessary and sufficient cause of group polarization whereas social comparison is neither necessary nor sufficient (the exclusivity hypothesis). Tlie correlational hypothesis. Several studies have shown that there is a good correlation between the preponderance of pro and con arguments possessed by group members and the size and direction of the postdiscussion polarization. For example, Madsen (1978) in Experiment 1, had subjects in one condition generate arguments pro and con on public sex education either in their own home state or in a geographically distant state. They then rated the persuasiveness of the arguments. In the second condition, eight groups of subjects completed pre- and postdiscussion ratings of their own support of sex education in their own home state, while eight groups of subjects performed the same task for sex education in a distant state. An index of average persuasiveness (Vinokur & Burnstein. 1974) derived from arguments for and against public sex education was highly predictive of the actual shifts towards greater or lesser support of public sex education. /"(13) = .51. across 16 groups of subjects with one covariate. In Experiment 2, Madsen used the same paradigm but changed the issue to be three CDQ-like scenarios involving drug usage. These three scenarios were crossed with a between-subjects manipulation of issue importance. Again, one large group totaling 50 subjects generated and ranked the persuasiveness of pro and con arguments, and 12 small groups totaling about 50 subjects completed pre- and postdiscussion ratings of their support of the courses of action proposed in the scenarios. Again, there was a high correlation between the average persuasiveness index for

1146

DANIEL J. ISENBERG

each scenario and the direction and magnitude of the observed choice shifts. r(4) = .82 and .64. by two alternative methods.8 These studies and one by Ebbesen and Bowers (1974, Experiment 1). r(9) = .65. suggest a high correlation between the preponderance of pro versus con arguments and choice shifts (see also Bishop & Myers. 1974: Vinokur& Burnstein, 1974. Experiment I). Nevertheless, as Madsen points out. there are examples of imperfect predictions from PAT. such as in his second experiment where two shift directions were incorrectly anticipated. He suggests that this may be due to the actual dynamics of howpersuasive arguments possessed by individual members may or may not work their way into the actual group discussion. Rather than surveying all of the relevant arguments, groups tend to be rather selective in their pursuance of limited lines of argumentation. Similarly, it has been observed in a number of studies that group members censor the arguments they put forth during discussion in order to support the emerging group consensus (cf. Ebbesen & Bowers, 1974. Experiment 2: Myers & Lamm. 1976. pp. 619-620). The causal hypothesis. Clearly, the establishment of a strong correlation between persuasive argument processing and group polarization is impressive, but it does not demonstrate a causal link. Accordingly, a number of studies have gone one step further and directly manipulated the preponderance of pro and con arguments in order to bring about corresponding shifts (e.g.. Burnstein & Vinokur, 1973, 1975; Burnstein et al., 1973: Ebbesen & Bowers, 1974, Experiments 2 and 3: Kaplan. 1977: Kaplan & Miller. 1977: Vinokur & Burnstein. 1978b). Ebbesen and Bowers (1974) in Experiment 3 had subjects listen to 10 risky and cautious arguments, while systematically varying the proportion of risky to cautious arguments from . I to .9. They found that the correlation between this proportion and polarization to risk was .98 across five different proportions (.1. .3. .5, .7. and .9). In other words, the higher the proportion, the greater the polarization to risk. When the proportion fell below .5, the group polarized to caution. More recently, Kaplan and Miller (1977) showed that subjects tended to recall persuasive arguments that they had been exposed to most recently rather than the ones they had been exposed to first. They then composed 24 six-person groups, half of which were in a redundant condition, and half of which were in a novel condition. Each subject in the redundant condition received six arguments, and the arguments were in the exact same order for each subject. Each subject in the novel condition received the same six arguments, but in a given group every subject received the six arguments in a different order. If subjects showed a recency effect and recalled the most recent argument, subjects in the redundant condition should recall the same argument, whereas subjects in the novel condition should recall different arguments. To the extent that recalled arguments were discussed more in the groups, subjects in the novel condition should be exposed to more novel arguments and thus should shift more. As predicted, the novel arguments groups showed a greater polarization effect. r(!40) = .67, although groups in both conditions polarized significantly. r( 140) = .76. Further studies have shown that group polarization is a function of an information pool within a group, where the pool consists of partially shared persuasive arguments (Kaplan. 1977, Experiment 3: Kaplan & Miller, 1977; Madsen. 1978: Vinokur &

Burnstein, 1974, I978a, 1978b). The greater the number of persuasive arguments that are novel or nonredundant in a group, the greater the impact of those arguments on group members. Thus, the partially shared (novel) arguments will have the most impact. In their second study, Vinokur and Burnstein (1978b) explored whether novel and valid arguments were in fact any more effective in causing shifts in predicted directions than non-novel arguments. In one condition, subjects received novel arguments that were prorisk mixed with non-novel arguments that were procaution. In the second condition, the same subjects received novel precaution and non-novel prorisk arguments. The prediction from the novelty-persuasiveness hypothesis would be that shifts would occur in the direction of the novel arguments. In fact, this was clearly the case, independent of whether the item was a typically risk- or caution-shifting item. In addition, risky items did shift to risk more than did cautious items, but the effect was weaker than the predicted effect. r ( 5 l ) = .93 versus .74. The effect of novelty was particularly strong for the neutral item, which shifted significantly in the direction of the novel arguments depending on whether they were prorisk or precaution. The exclusivity hypothesis. A number of studies have attempted to show that PAT is necessary and sufficient to produce polarization effects and that only PAT can account for these effects. The most recent of these will be reviewed here (Burnstein & Vinokur. 1975; Laughlin & Earley. 1982; Vinokur & Burnstein. 1978a: see also Burnstein & Vinokur, 1973: Burnstein et al., 1973). One study (Burnstein & Vinokur, 1975) was designed to show that exposure to others' positions (mere-exposure) causes people to privately generate persuasive arguments, which in turn produces polarization. These authors attempted to demonstrate that exposure to others' positions causes polarization only when it stimulates the generation of persuasive arguments. In a withinsubjects design. 12 groups of 5 subjects responded to three risky CDQ items in three conditions (after having completed one CDQ item as practice). In the major experimental condition, subjects responded to one of the three items, were exposed to each other's responses, privately generated arguments for and against risk for that item, and then responded again to the same CDQ item. An exposure control condition was identical to the experimental condition except that subjects privately generated arguments for and against risk for a different item (the practice item). Thus, subjects in this condition were prevented both from thinking about others' responses and from generating relevant arguments. A no-exposure control condition had subjects respond to a CDQ item, privately generate arguments, and respond to the same CDQ item again. Thus, the first condition purportedly shows the effects of exposure on argument generation, which is hypothesized to mediate the effects of exposure on polarization. The authors found a risky shift in the experimental condition, r( 11) = .89, a nonsignificant cautious shift in the exposure control, r = .43,' and no shift in the no-exposure control, r = .03. The experimental condition polarized to risk significantly more

8 The second correlation is a more conservative post hoc analysis that I conducted on Madsen's data. 9 We are not told which item was used as a practice item, but it is conceivable that subjects generated precaution arguments that then generalized to the focal item, thus attenuating the usual polarization to risk.

GROUP POLARIZATION

1147

than the other two conditions, r(22) = .68. In comparing the balance of actual prorisk and procaution arguments generated by subjects in the experimental and no-exposure conditions, it was found that the weight and number of prorisk arguments was greater in the experimental conditions, whereas this was not true for the procaution arguments. Although the difference between prorisk and procaution arguments was significant for the experimental condition but not for the no-exposure condition, the difference between these conditions was apparently not significant as should have been predicted by the model. This is an admirable study in its use of content analysis, in the strength of the findings, and in its specific predictions that were tested by planned comparisons.'0 Nevertheless, there are some aspects of the study that are vulnerable to criticism. The major criticism is that Burnstein and Vinokur (1975) first distorted the SCT position somewhat and then attacked the distortion. For example, in the exposure control condition the experimenter prevented subjects from thinking after they had been exposed to others' positions by immediately giving them a task to generate arguments for a different item. In a very real sense this was a distraction task. The implicit assumption is that social comparison processes require no thought. However, this is not the case; information processing in SCT must occur at two junctures, the first being in processing the fact that others are different from what one had expected, and the second being in the cognitive calculus of how to be different from the average "in the right direction and to the right degree." Burnstein and Vinokur (1975) also assumed the role of strong emotion in social comparison processes, stating that group members are supposed to be "distressed" (p. 414). "disturbed," or "surprised" (p. 417) by discovering that they are not as different from others as they had previously thought. To my knowledge, nowhere is such emotion suggested by advocates of social comparison theory." In one of the most thorough and innovative studies of group polarization, Vinokur and Burnstein (1978a) argued that in most cases, PAT and SCT make similar predictions about the direction of polarization, except for the case when two subgroups with divergent positions (one pro-J and the other pro-K) try to reach a decision. In this situation, SCT holds that each member of the pro-K. subgroup will compare himself to the members of his own subgroup and then become more pro-K after discussion, whereas members of the pro-J subgroup will become more pro-J. The result will be polarization between subgroups. PAT argues that within each subgroup most of the arguments favoring a given alternative will have been shared already and thus there will be relatively few novel (and thus persuasive) valid arguments within subgroups. Across subgroups, however, new arguments will be heard, thus facilitating a shift toward the other subgroup, and depolarization will be observed. In the first of two experiments, subjects first completed seven CDQ items: four risky, two cautious, and one neutral. On the basis of their responses, experimenters composed several groups of six members for each item (in other words, groups were formed for one item, then re-formed for the next item, and so on). The criterion for forming each group was that there were two subgroups of 3 subjects, and for the particular item to be discussed the average responses for the two subgroups differed by approximately 5 scale points (out of 10). For half of the groups, a salience manipulation had the three subgroup members sit together op-

posite the other subgroup with the labels ("Risky Subgroup" and "Cautious Subgroup") in front of them. For the other groups, members simply sat together. In both conditions group members discussed each CDQ item with the instructions to attempt to reach consensus. After responding to all of the items in seven different subgroupings. subjects made their postdiscussion ratings on all seven items. The measure of attitude polarization was postdiscussion minus prediscussion ratings. The measure of depolarization was the difference between the means of each of the two subgroups of 3 subjects each.1' The findings of Experiment 1 were clear: both polarization of the total groups of 6 and depolarization between the two subgroups of 3 occurred, the latter being two to three times as large as the former. These effects apparently were equivalent for groups in the salient and nonsalient subgroup conditions (effect sizes are not given, nor do we know if the effects were in the predicted direction). Groups polarized to risk on risky items and to caution on cautious items, but overall the two subgroups showed a strong tendency to converge toward one another. r( 17) = .87. l3 Analyses of the subgroups showed that on the risky items the cautious subgroups shifted more toward risk than did the risky subgroups shift toward caution. Likewise, on the cautious items the risky subgroups shifted more toward caution than did the cautious subgroups shift toward risk. On the neutral item both subgroups tended to shift (depolarize) toward each other. Experiment 2 replicated and extended these findings but instead of the CDQ items, subjects responded to two value items (e.g., "Do you think capital punishment is not justified under any circumstances or is justified for special cases of murder?"), two personal taste items (e.g., "Is football or basketball more interesting to watch?"), and three factual items (e.g., "When will the LInited States become independent of foreign sources of energy?"). Otherwise, the procedures were identical to those used in Experiment 1. Again, there were apparently no effects of subgroup salience (again, no effect directions or sizes were reported), both polarization (on six of the seven items) and depolarization occurred, and depolarization was stronger (on six of the seven items). In both cases, the exception was the capital punishment item. With two exceptions both subgroups shifted toward each other, accounting for the large depolarization effect, r(2Q) = .84 (see Footnote 13: again, the capital punishment item was one of the two exceptions). Finally, combining the findings from both experiments, depolarization was greatest for factual

One wonders wh> a 2 x 2 analysis of variance was not used to test the predicted interaction of condition with balance of prorisk/procaution arguments. " There is a confound in the comparison between the experimental and the no-exposure control conditions, namely that subjects always responded to the no-exposure control condition first when participating in the experiment. Then the remaining two conditions were counterbalanced. It is conceivable that subjects needed to warm up to the experimental situation, and this caused them to generate arguments of different kinds in the first trial (i.e.. the no-exposure control condition). i: An additional group of subjects completed the two CDQ items and seven items used in Experiment 2 in order to control for regression to the mean. 13 This effect size is based upon the average of seven is for the depolarization score on each item, as well as on the harmonic mean. A slightly different number of groups was used for each of the seven items.

10

1148

DANIEL J. ISENBERG

items (3.92), second for the CDQ items (2.44), third for taste (1.90), and fourth for value (1.01). These two experiments are quite interesting primarily because they are surprisingly the first to study polarization between subgroups. This remains a serious shortcoming in the group polarization literature. The authors interpret their results as showing that PAT makes an accurate prediction (depolarization) whereas SCT makes an inaccurate one (polarization between subgroups). A more cautious interpretation would be that here is yet another demonstration of postdiscussion convergence (see Myers. 1982) occurring along with an average shift, where the members most extreme in the direction of polarization shift less compared to those most extreme in the opposite direction (see Ferguson & Vidmar. 1971). Whether or not these two experiments actually test SCT depends upon how much we believe that the salience manipulation in fact caused group members to compare themselves to the other 2 members of their own subgroup. I think this can be reasonably questioned given (a) the instructions to "reach consensus." (b) the fact that all subjects were students at the same university, and (c) that the students may have adhered to norms of conflict avoidance. Given the choice between being less extreme and avoiding conflict, versus comparing themselves to their own subgroup and becoming more extreme, I think that most students would choose the former, independent of any persuasive arguments. It is to the credit of PAT that its specificity allows anomalies to be informative, and the anomaly of the capital punishment item is instructive because it is the only item showing both significant polarization and no depolarization. Data presented in the article indicate that the polarization was against capital punishment, due primarily to nonliberal subjects becoming more liberal. According to PAT, this could occur only if (a) the liberal subgroup did not hear any new arguments for capital punishment, and (b) the nonliberal subgroup did hear novel arguments against capital punishment. There is no evidence that this was the case: in fact, the authors themselves argue that for value items, novel arguments are essentially exhausted. A simpler alternative explanation to the data on the capital punishment item is that discussion engaged a liberal norm in a liberal setting, and that attitudes polarized accordingly, a typical finding in polarization research (Myers, 1975: Myers & Bach, 1974). The Vinokur and Burnstein (1978a) studies do pose a critical question for group research in general, namely, under what circumstances should polarization between groups occur? Would it be possible for polarization between groups to occur if both groups (for example, Palestinians and Israelis) was exposed to the same arguments and the argument pool is exhausted? Everyday experiences in families, labor relations, and international politics suggest that such argument-poor polarization can occur (Sherif, 1966). PAT itself suggests a way to understand how this might happen, namely that the arguments generated and processed are novel but they are rejected as invalid (Vinokur & Burnstein, 1978b). However, this puts us back in the arena of normative mechanisms because the perception of validity is by definition value based. This point is reinforced by the finding that novelty leads to persuasiveness only when perceived validity is high (Vinokur & Burnstein, 1978b). Given the ubiquity of intergroup phenomena (e.g., Sherif, 1966) we would expect that when an outgroup is perceived as "bad," their arguments will be

perceived as invalid, and thus novel arguments (and rational discussion) will be unpersuasive. Without siding with either SCT or PAT. it seems that the perception of validity is one important conceptual link between the two. A final exclusivity study by Laughlin and Earley (1982) reportedly found stronger support for PAT than for SCT based on the observation that, across CDQ items, repeated trials, and conditions (individual vs. group), decisions taking the perspective of a hypothetical stranger were riskier than those taking the perspective of a friend or oneself. Why is this counter to SCT? Laughlin and Earley argued that the hypothesized desire to be better than the average in SCT should manifest itself primarily when making decisions from one's own perspective and not when making decisions from the stranger perspective. Thus when risk is valued, one should rate oneself as riskier than the stranger, and when caution is valued one should rate oneself as more cautious. Curiously, Laughlin and Earley used the perspective main effect to test this hypothesis rather than the item by perspective interaction. Whereas they concluded that SCT has a problem because across items the self perspective is more cautious than the stranger perspective, there is nothing in SCT that would predict a perspective main effect at all. The more appropriate item perspective by interaction yields an F less than 1, F(\, 564) = .07. This might still be considered a problem for SCT. but certainly a relatively minor one.14

Summary and Conclusions

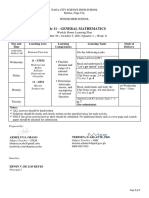

Table 1 summarizes the effects from the more recent studies showing effects either of mere-exposure or of persuasive arguments. The average effect sizes from each type of study are substantial, but the effect of persuasive argumentation is particularly strong (.746 average r vs. .436)." In many of the studies reported here, both social comparison and persuasive argumentation are occurring simultaneously, but there are studies that show effects of social comparison in argument-poor tasks (e.g.. Baron & Roper, 1976: see also Myers, 1982: Vidmar, 1974). There are also studies that show effects of argumentation in comparison-poor tasks (e.g..

14 One source of potential support for the exclusivity hvpothesis has been the relative lack of effects of mere-exposure to other group members" positions compared to exposure to persuasive arguments. For example. Kaplan (1977. Experiment 2) found that when confronted with two contradictory sources of influence, proincrimination persuasive arguments and proexoneration ratings of group members, the persuasive arguments influenced subjects' subsequent ratings, whereas mere-exposure did not. Care should be taken, however, in interpreting this finding as evidence for the exclusivitv hypothesis. An alternative interpretation would be that a written list of proincrimination arguments would be more vivid and salient (Borgida and Nisbett. 1977) than a set of numbers representing members' proexoneration positions. 15 Some care must be exercised in interpreting this difference in average effect size. Data reported in several of the PAT studies (e.g.. Vinokur & Burnstein. 1974) allow the calculation of the correlation between predicted and observed scores across CDQ or similar items. Given the lack of an appropriate within subjects error term, it is not possible to calculate an r that is directly comparable with the other. Thus, several of the reported rs probably are higher than they would be based on an appropriate error term with <# based on number of subjects, not number of items.

GROUP POLARIZATION Burnstein et al., 1973; Ebbesen & Bowers, 1974), that is, tasks that do not permit the inference of group comembers' positions. In the cases of the argument-poor studies the effect sizes are very similar to the average effect size for mere-exposure studies. Likewise, for comparison-poor studies, the effect sizes are similar to the average effect size for persuasive arguments studies. At this point in time there is very good evidence that there are two conceptually independent processes even though outside of the laboratory they almost always co-occur. The analysis of effect sizes is important for both the planning

1149

Table 1 Effect Sizes for Recent Group Polarization Studies on Mere-Exposure and Persuasive Argumentation

Stud>

Mere-exposure studies" Baron & Roper (1976) Experiment 1 Experiment 2 Bell &Jamieson( 1970) Bell & Jamiesonf 1970) Blascovich. Ginsburg. & Veach ( 1975) Blascovich, Ginsburg. & Howe (1975) Blascovich. Ginsburg. & Howe (1976) Blascovich & Ginsburg (1974) Blascovich & Ginsburg (1974) Clark &Willems( 1969) Clark &Willems( 1969) Goethals& Zanna(l979) Myers (1978) Experiment 1 Experiment 1 Experiment 2 Myers, Bach, & Schreiber (1974) Myers. Bruggink, Kersting, & Schlosser (1980) Experiment 1 Experiment 2 Myers, \\ojcicki. & Aardema ( 1977) Teger& Pruitt(l967) Wallach& Kogan(1965) Wallach& Kogan(1965)

'a.t

df

.41 .43 .12 .21 .37

.74

44 39

.39 .29 .57 .52 .36 .63 .27

.44

23 23 14 7 17

27 27 24 24 14

102a

of future experiments as well as the interpretation of past ones. For example, Burnstein & Vinokur (1977) cited the lack of mereexposure effects in several studies, but reanalyses suggest effect sizes that are respectable (.3-.4) but insignificant perhaps as a result of the small number of subjects in the experiment. For example. Clark and Willems (1969) found that information exchange of positions led to no shift in one of their conditions. t(24) = 1.87, whereas the associated r(.36) is very similar to those in Table I. Thus, the conclusion that this is a failure to replicate is not necessarily founded in this study (a Type 2 error may have been committed). On a related point, many investigators have made it difficult to perform meta-analyses and at the same time impeded tests of specific hypotheses by using omnibus F-tests (with df(num) greater than 1). These make the translation to r difficult and test only the general (and conceptually meaningless) hypothesis that there is some significant amount of variance associated with the independent variables. Given the maturity of the field and accumulated knowledge of the effects of various stimuli, very specific a priori hypotheses can and should be stated using planned contrasts. A discussion of this technique is beyond the scope of this article (see Winer, 1971), but any number of degrees of freedom in the numerator other than 1 should be a warning flag for researchers (Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1984).

Integrative Questions

Given the support for both PAT and SCT as mediating processes, it behooves investigators to develop theories that account for the interaction between SCT and PAT and that address the factors that moderate the emergence of one or the other form of influence. The following are four questions that suggest how to integrate PAT and SCT into a more conceptually coherent position, a position that also serves to integrate group polarization with other social psychological phenomena. Under what conditions will group processes be more affected by either rational argumentation or social comparison? One potential moderating variable is decision characteristics. To the extent that a decision has many factual or logical components we would expect rationality to be more prominent than social desirability. The items that Vinokur and Burnstein (1978a) showed to depolarize the most in group discussion (i.e., be less susceptible to social comparison processes) were those involving matters of fact. A different potential moderating variable is ego involvement. In a decision where group members are highly ego-involved several parameters change: (a) values are engaged; (b) attention is constricted to a narrow range of information input and issues; and (c) argument pools tend to be exhausted because ego-involving issues have already been heavily processed by individuals prior to discussion. We would expect capital punishment, feminism, pacifism, and drug usage to be ego-involving compared to the CDQ scenarios and questions of whether basketball or football is the more interesting spectator sport. Thus social comparison should operate more strongly in the former situations, and persuasive argumentation should operate more strongly in the latter. H 'hat are the causal paths among social desirability, persuasive argumentation, and attitude polarization? Myers and Lamm

.33 .52 .86 .43

.17 .51 -.03

102 116

18 18 27 265 18 II 11

.37

.436

Persuasive arguments studies Burnstein & Vinokur (1975) Burnstein. Vinokur, & Trope (1973) Ebbesen & Bowers (1974) Experiment 1 Experiment 3 Kaplan (1977) Experiment I Experiment 2 Kaplan & Miller (1977) Madsen(l978) Experiment 1 Experiment 2 Vinokur & Burnstein (1974) Experiment I Experiment 2 Experiment 3

.68 .39 .65 .98 .44 .53 .67 .51 .57 .86 .93 .84 .746 22 252 9 3 88 88

140

13 4 3 3 3

" These two correlations are not independent, thus the average of these two correlations (.408) was used in computing the average r for all of the mere-exposure studies.

1150

DANIEL J. ISENBERG

(1976) suggested that social desirability can influence argumentation through action commitment, but that persuasive arguments do not affect social desirability (Myers & Lamm. 1976, Figure 1). The distinction between rationality and rationalization is germane here and needs to be paid attention to in particular by the persuasive arguments theorists. The former implies argumentation in the absence of social desirability, whereas the latter suggests that social desirability can motivate persuasive argumentation. Action commitment helps, but it is not necessary for the internal generation of arguments to reduce dissonance with socially desirable positions. In overt group interaction, normative processes can do more than motivate group members to think of supporting arguments; they can also cause members to skew their spoken arguments to favor one alternative over another. As Myers and Lamm (1976) argued, self-censoring probably occurs in group decision making. If so, we might hypothesize that the greater the pluralistic ignorance in a group prior to discussion, the greater the amount of self-censoring that will be observed as members attempt to conform to the misperceived norm. As in release theory, when the true norms are discovered, self-censoring will still occur, but in the opposite direction as members strive to be better than the average. Hmv is information about group members' positions combined into a mental concept of the "group norm"? What are the processes by which group members attend to, encode, and store information about these descriptive and prescriptive norms within their group? This issue reverses the causal sequence in the second question above (normative cognitive) and suggests that informational processes can influence normative ones. Thus, certain characteristics of information such as vividness (Taylor & Fiske, 1978) can influence how group members perceive their group's norms. For example, it is possible that information about extreme or deviant group members is cognitive!}1 overavailable and will have an inordinate influence in determining perceptions of norms. An obvious area of research is the relation between social cognition and group polarization. Burnstein (1982) has already begun to establish links between polarization and information processing. Hmv can group polarization phenomena be related to attitude change processes in general (e.g.. Sherif& Holland, 1961) and attitude polarization in particular? One distinction typically made in the attitude change literature is between source and message characteristics (McGuire, 1969). The debate between PAT and SCT can be recast in these terms. For example, social comparison theorists indirectly focus on who or what is the source of the norms that form the basis for social comparison. If the source is a reference group of similar others, then a perceived discrepancy between own and others' positions should generate group polarization. Persuasive argument theorists seem to disregard the source and differentiate among message characteristics, such as novelty and validity. When seen in this light, one reason the two positions do not see eye to eye is that they are dealing with different aspects of a more generalized process of attitude change. Quite unwittingly. James Stoner opened up an important subfield of research in small group behavior that has resulted in several robust conclusions. It is hoped this research will continue in such a way that it becomes integrated with other important

theoretical streams in social psychology as well as with the practical requirements of functioning in real-life groups.

References

Anderson. N. H., & Graesser. C. C. (1976). An informational integration analysis of attitude change in group discussion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 34, 210-222. Baron, R. S.. & Roper. G. (J976). Reaffirmation of social comparison views of choice shifts: Averaging and extremity effects in an autokinetic situation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 33, 521 -530. Bell. P. D.. & Jamieson, R. B. (1970). Publicity of initial decision and the risky-shift phenomenon. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 6. 329-345. Bishop. G. D.. & Myers, D. G. (1974). Informational influences in group discussion. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance. 12, 92104. Blascovich, J.. & Ginsburg, G. P. (1974). Emergent norms and choice shifts involving risk. Sociometry. 37, 205-218. Blascovich, J.. & Ginsburg. G. P. (1978). Conceptual analysis of risktaking in "risky-shift" research. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 8. 217-230. Blascovich. J., Ginsburg, G. P.: & Howe, R. C. (1975). Blackjack and the risky shift. II: Monetary stakes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, I I . 224-232. Blascovich, J.. Ginsburg, G. P.. & Howe. R. C. (1976). Blackjack, choice shifts in the field. Sociometry, 39. 274-276. Blascovich, J., Ginsburg. G. P.. & Veach. T. L. (1975). A pluralistic explanation of choice shifts on the risk dimension. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 422-429. Borgida, E., & Nisbett. R. E. (1977). The differential impact of abstract vs. concrete information on decisions. Journal of Applied Social Psvchology, 7. 258-271. Brown. R. (1965). Social psychology. New York: Free Press. Brown. R. (1974). Further comment on the risky shift. American Psychologist, 29. 468-470. Burnstein. E. (1982). Persuasion as argument processing. In H. Brandstatter. J. H. Davis. & G. Stocher-Kreichgauer (Eds.), Contemporary problems in group decision-making (pp. 103-124). New York: Academic Press. Burnstein, E.. & Vinokur. A. (1973). Testing two classes of theories about group-induced shifts in individual choice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 9. 123-137. Burnstein. E., & Vinokur. A. (1975). What a person thinks upon learning he has chosen differently from others: Nice evidence for the persuasive arguments explanation of choice shifts. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 11,412-426. Burnstein, E.. & Vinokur, A. (1977). Persuasive argumentation and social comparison as determinants of attitude polarization. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 13. 315-332. Burnstein. E., Vinokur. A.. & Trope. Y. (1973). Interpersonal comparison versus persuasive argumentation: A more direct test of alternative explanations for group-induced shifts in individual choice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 9, 236-245. Cartwright, D. (1973). Determinants of scientific progress: The case of research on the risky shift. American Psychologist, 28, 222-231. Clark. R. D. (1971). Group-induced shift towards risk: A critical appraisal. Psychological Bulletin, 76, 251-270. Clark. R. D., & VVillems, E. P. (1969). Where is the risky shift? Dependence on instructions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13. 215221. Ebbesen, E. B.. & Bowers, R. J. (1974). Proportion of risky to conservative arguments in a group discussion and choice shifts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29, 316-327. Ferguson. D. A.. & Vidmar. N. (1971). Effects of group discussion on

GROUP POLARIZATION estimates of culturally appropriate risk levels. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 20, 436-445. Festinger. L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7. 117-140. Fromkin. H. (1970). Effects of experimentally aroused feelings of undistinctiveness upon valuation of scarce and novel experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 16. 521-529. Goethals. G. R.. & Darley. J. (W). Social comparison theory. An attributional approach. In J. Suls & R. Miller (Eds.), Social comparison processes: Theoretical and empirical perspectives (pp. 259-278). Washington, DC: Hemisphere Press. Goethals. G. R.. & Zanna. M. P. (1979). The role of social comparison in choice shirts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 3~. 14691476. Hong. L. K. (1978). Risky shift and cautious shift: Some direct evidence on the cultural-value theory. Social Psychology. 41. 342-346. Isenberg, D. J. (1980). Levels of analysis of pluralistic ignorance phenomena: The case of receptiveness to interpersonal feedback. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 10. 457-467. Isenberg. D. J.. & Ennis. J. G. (1981). Perceiving group members: A comparison of derived and imposed dimensions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology; 41. 293-305. Jellison. J.. & Arkin, R. (1977). Social comparison of abilities: A selfpresentation approach to decision-making in groups. In J. Suls & R. Miller (Eds.). Social comparison processes.- Theoretical and empirical perspectives (pp. 235-258). Washington. DC: Hemisphere Press. Jellison. J.. & Riskind. J. (1970). A social comparison of abilities interpretation of risk-taking behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 15. 375-390. Jones, E. E.. & Nisbett. R. E. (1972). The actor and the observer: Divergent perceptions of the causes of behavior. In E. E. Jones, E. E. Kanouse. H. H. Kelley. R. E. Nisbett, S. Valins. & B. \Veiner(Eds.). Attribution. Perceiving the causes of behavior. Morristown. NJ: General Learning Press. Kaplan. M. F. (1977). Discussion polarization effects in a modified jury decision paradigm: Informational influences. Sociomeir): 40, 262-271. Kaplan. M. F. & Miller. C. E. (1977). Judgments and group discussion: Effect of presentation and memory factors on polarization. Sociomeln: 40. 337-343. Kleinhans. B.. & Taylor. D. A. (1976). Group processes, productivity, and leadership. In B. Seidenberg & A. M. Snadowsky (Eds.). Social psychology (pp. 407-434). New York: Free Press. Lamm. H.. & Myers, D. G. (1978). Group-induced polarization of attitudes and behavior. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.). Advances in experimental social psychology (Vo\. 2, pp. 147-195). New York: Academic Press. Laughlin, P. R.. & Earley. P. C. (1982). Social combination models, persuasive arguments theory, social comparison theory, and choice shifts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 42. 273-280. Levinger. G., & Schneider. D. J. (1969). Test of the "risk is a value" hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. I I . 165-169. Madsen. D. B. (1978). Issue importance and choice shifts: A persuasive arguments approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 36. 1118-1127. McGuire, W. J. (1969). The nature of attitudes and attitude change. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.). The handbook of social psychology (2nd ed.. pp. 136-314). Reading. MA: Addison-Wesley. Moscovici. S., & Zavalloni. M. (1969). The group as a polarizer of attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 12. I25-135. Myers, D. G. (1975). Discussion-induced attitude polarization. Human Relations, 28, 699-714. Myers. D. G. (1978). Polarizing effects of social comparison. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 14. 554-563. Myers. D. G. (1982). Polarizating effects of social interaction. In H. Brandstatter, J. H. Davis. & G. Stocher-Kreichgauer (Eds.). Contem-

1151

porary problems in group decision-making (pp. 125-161). New York: Academic Press. Myers, D. G., & Bach. P. J. (1974). Discussion effects on militarismpacifism: A test of the group polarization hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30. 741-747. Myers. D. G.. Bach. P. J.. & Schreiber, F. G. (1974). Normative and informational effects of group interaction. Sociometry. 37, 275-286. Mvers. D. G.. Bruggink. J. B., Kersting, R. C.. & Schlosser, B. A. (1980). Does learning others' opinions change one's opinion? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 6. 253-260. Myers. D. G., & Lamm. H. (1975). The polarizing effect of group discussion. American Scientist, 63. 297-303. Myers, D. G.. & Lamm, H. (1976). The group polarization phenomenon. Psychological Bulletin. 83. 602-627. Myers. D. G., Wojcicki. S. B.. & Aardema, G. C. (1977). Attitude comparison: Is there ever a bandwagon effect? Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1. 341-347. Pruitl, D. G. (197 la). Choice shifts in group discussion: An introductory review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 20, 339-360. Pruitt, D. G. (197lb). Conclusions: Toward an understanding of choice shifts in group discussion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 20.495-510. Rosemhal. R. (1978). Combining results of independent studies. Psychological Bulletin. 85, 185-193. Rosenthal. R., & Rosnow, R. (1984). Essentials of behavioral research. New York: McGraw-Hill. Sanders. G. S., & Baron, R. S. (1977). Is social comparison irrelevant for producing choice shifts? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 13. 303-314. Schroeder, H. E. (1973). The risky shift as a general choice shift. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 27. 297-300. Sherif. M. (1966). In common predicament. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Sherif. M.. & Hovland. C. (1961). Social judgment. New Haven. CT: Yale University Press. Stoner, J. A. F. (1961). A comparison of individual and group decisions involving risk. Unpublished master's thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Cambridge, MA. Stoner, J. A. F. (1968). Risky and cautious shifts in group decisions: The influence of widely held values. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 4. 442-459. Taylor, S. E.. & Fiske, S. (1978). Salience, attention, and attribution: Top of the head phenomena. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (\'o\. 11, pp. 250-288). New York: Academic Press. Teger. A. I., & Pruitt, D. G. (1967). Components of group risk taking. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 3. 189-205. Vidmar, N. (1974). Effects of group discussion on category width judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 29, 187-195. Vinokur. A.. & Bumstein. E. (1974). Effects of partially-shared persuasive arguments on group-induced shifts: A group-problem-solving approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 29. 305-315. Vinokur, A.. & Burnstein. E. (I978a). Depolarization of attitudes in groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36. 872-885. Vinokur. A.. & Burnstein. E. (I978b). Novel argumentation and attitude change: The case of polarization following group discussion. European Journal of Social Psychology, 8, 335-348. Wallach. M. A.. & Kogan. N. (1965). The roles of information, discussion, and consensus in group risk-taking. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, I. 1-19. Winer, B. J. 11971). Statistical principles in experimental design. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Received July 3, 1984 Revision received March 22, 1985

Вам также может понравиться

- Sequences and Series Integral Topic AssessmentДокумент6 страницSequences and Series Integral Topic AssessmentOrion BlaqueОценок пока нет

- Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: The Self-And Other-Interest InventoryДокумент21 страницаJournal of Personality and Social Psychology: The Self-And Other-Interest InventoryCatarina C.Оценок пока нет

- Bottoms y Sparks - Legitimacy - and - Imprisonment - Revisited PDFДокумент29 страницBottoms y Sparks - Legitimacy - and - Imprisonment - Revisited PDFrossana gaunaОценок пока нет

- Party Brands and Partisanship: Theory With Evidence From A Survey Experiment in ArgentinaДокумент16 страницParty Brands and Partisanship: Theory With Evidence From A Survey Experiment in ArgentinaKeys78Оценок пока нет

- Prejudice SechristДокумент25 страницPrejudice SechristZsuzsi AmbrusОценок пока нет

- GerberEncyclopedia PDFДокумент9 страницGerberEncyclopedia PDFANNURRIZA FIRDAUS RОценок пока нет

- Marketing, El Lado OscuroДокумент46 страницMarketing, El Lado OscurovitorperonaОценок пока нет

- Social Movement Rhetoric Anti Abortion PDFДокумент26 страницSocial Movement Rhetoric Anti Abortion PDFEl MarcelokoОценок пока нет

- Norm ClarityДокумент10 страницNorm ClarityMaja TatićОценок пока нет

- Identity and Emergency Intervention: How Social Group Membership and Inclusiveness of Group Boundaries Shape Helping BehaviorДокумент34 страницыIdentity and Emergency Intervention: How Social Group Membership and Inclusiveness of Group Boundaries Shape Helping BehaviorJodieОценок пока нет

- Current Research in Social PsychologyДокумент16 страницCurrent Research in Social PsychologyCosmina MihaelaОценок пока нет

- Literature Review PaperДокумент24 страницыLiterature Review Paperapi-564599579Оценок пока нет

- Communication in Small GroupsДокумент12 страницCommunication in Small GroupslyyОценок пока нет

- DiMaggio, Evans y Bryson - Have Americans Social Attitudes Become More Polarized 2 (1996)Документ86 страницDiMaggio, Evans y Bryson - Have Americans Social Attitudes Become More Polarized 2 (1996)Leandro Agustín BruniОценок пока нет

- Liu 2012Документ16 страницLiu 2012Iber AguilarОценок пока нет

- Art - Hornsey-2008 Self Categorization PDFДокумент19 страницArt - Hornsey-2008 Self Categorization PDFUmbelino NetoОценок пока нет

- Prejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination 3Документ26 страницPrejudice, Stereotyping and Discrimination 3Veronica TosteОценок пока нет

- Manuscript Gomila Paluck Preprint Forthcoming JSPP Deviance From Social Norms Who Are The DeviantsДокумент48 страницManuscript Gomila Paluck Preprint Forthcoming JSPP Deviance From Social Norms Who Are The DeviantstpОценок пока нет

- Locus of Control and Social Support: Interactive Moderators of StressДокумент13 страницLocus of Control and Social Support: Interactive Moderators of StressFajrin AldinaОценок пока нет

- Cognitive Dissonance TheoryДокумент44 страницыCognitive Dissonance TheoryAde P IrawanОценок пока нет

- Experimentul Lui Sherif MuzaferДокумент17 страницExperimentul Lui Sherif MuzaferRamona Cocis100% (1)