Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

3 Sexes 4 Sexualities

Загружено:

jazzica15Исходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

3 Sexes 4 Sexualities

Загружено:

jazzica15Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Three Sexes and Four Sexualities: Redressing the Discourses on Gender and Sexuality in Contemporary Thailand

Rosalind C.Morris

All archetypes are spurious but some are more spurious than others.-Angela

and the Ideology of Pornography

Carter, The Sadezan Woman

Preliminaries

Few nations have been so thoroughly subject to Orientalist fantasies as has Thailand. Famed for its exquisite women and the pleasures of commodified flesh, the Thailand of tourist propaganda and travelogues is a veritable bordello of the Western erotic imaginary. And yet, despite the aura of sexual excess that infects both local and Western representations, there has been little systematic analysis of sexual identities outside of sex-role theory in Thailand, nor has there been any sustained attempt to situate Thai concepts of bodily order in a historical context. In general, the ethnopositions 2:10 1994by Duke University Press.

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

16

graphic literature has accepted modern Theravada Buddhist orthodoxy,l ironically reproducing its denial of sensual pleasures and its proscriptive images of essential, reproductively oriented gender difference. With a few notable exceptions, sexual identity and erotic experience -especially heterodox identities and experiences- are palpable absences, which is to say suppressed presences, in the scholarly literature. This essay seeks to redress that omission. At the same time, it takes arms against popular traditions that have fetishized Thai bodies in what can only be described as a representational sex trade of desire. And it endeavors to illuminate the interrelations between scholastic and popular inscriptions while addressing that tendency so endemic to gender-bending studies by which sexual otherness is ironically neutralized through its specularization. I begin with an exemplary instance of the latter from Nan Goldins new book, The Other Side.2 Somewhere in the middle of The Other Side is a pair of photographs taken in the back room of a Bangkok burlesque club. T h e bottom image is particularly arresting-in the sense that it induces both the curiosity and the thralldom of the trompe loeil. Looking out from the glossy page from a harshly lit, rather tawdry backdrop is a disrobed figure, frontally nude. We see a delicate face startled by red lipstick. Its almond eyes are perfectly accented with liner and mascara, its cheekbones lifted by rouge from powdered skin. And beneath: full breasts which are not simply unveiled by the camera but which seem to exhibit themselves for the camera. This delicate woman is pure Orientalist fantasy3- except that this is a man. O r rather, this is a photograph of a kathoey, a category that includes male transsexual and transvestite identities in Thailand. In Goldins book about drag queens from around the world, kathoeys appear as just one instance of what the photographer suggests is a transnational system of subversive sexuality. Assuming normative heterosexuality in a biological mode, this ostensibly radical vision then constructs a normative form of subversive sexuality: the drag queen becomes a de facto hero in a global sexual resistance. In this respect, Goldins work shares much with contemporary gender theories, epitomizing the ironic homogenization of differences that emerges when kathoey and other forms of alterior sexual identity are considered in fetishisms vacuum, independent of the culturally specific sedgender systems from which they emerge. T h e moment that

Morris

Three Sexes and Four Sexualities

17

sexual identity is considered in its relation to other forms of subjectivity and subjectification, of course, such equalization becomes untenable. Like Goldins imagery, much of the contemporary literature on gender and difference focuses on specularized forms of sexual identity. But such presentations of self can never be metonyms for the sedgender systems from which they arise. Their particular nature is determined by the theatrics of commodity exchange. Accordingly, professional drag queens or professional kathoeys tell us about the forms of professional drag and little more.5 We need to look elsewhere for an understanding of sedgender systems- to the entire range of sexual practices and identities available within a particular social formation. As we do so, we need also to be aware of the masculinist bias that has dominated the imagery of alterior sexuality and to ask how resistance and transgression are themselves differentiated along the lines of sex and gender. In the following pages, I outline what I believe to be the crucial and distinguishing characteristics of a social landscape inhabited by two radically different sedgender systems, one a trinity of three sexes, the other a system of four sexualities. Throughout this essay, I use the termgender, in the tradition of feminist anthropology, to signify the social forms and symbols of sexual identity as they are constructed in reference to culturally specific rhetorics of the body.6 The ideological work of sedgender systems is, of course, the naturalization of social order. Thus gender is always naturalized as sexual identity, but sexual identity is not always a matter of sexual practice and perhaps only rarely a matter of object choice. As Foucault has argued, sexuality denotes a form of identity that emerges within the structures of modern capitalist production, where sexual relations are abstracted and reified through the logic of commodity exchange as forms of consumption and, hence, of object choice. For this reason, a history of sedgender systems must always be an analysis of the changes in politico-economic order. I do not, however, mean to suggest a linear progression from one system to the other. While they emerge in sequence, there is no necessary telos of integration and rationalization. Both exist in the present and vie for hegemony in a society that is deeply influenced but not fully determined by transnational forces and ideologies. T h e resulting contradictions can induce some head-spinning experiences for those from without.

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

18

On the Spuriousness of Archetypes

Recently, a friend and sister field researcher in Chiang Mai remarked that she had been to a convenience store late one evening and found herself the only person among many (male and female) who was not flamboyantly cross-dressed. T h e scene was, she said, a marvelous and self-consciously performative game of homoerotic flirtation. Her experience was not unique; like her, I have often found myself astounded by the plasticity and heterogeneity of Thai gender and sexual identity. At least part of that dismay stems from the fact that we are all constrained-with more or less comfort- by normative ideologies. And in Thailand, the dominant representations of sex and gender are focused in and through fetishistic notions of ideal feminine beauty as it is constructed for a heterosexual male gaze. In this context, transvestism can undercut or redefine the presumed relationship of desire between male viewer and female viewed, interrupting the expectations of fulfillment with a veil that reveals itself more than the object of consummation. This is, I think, what was happening in the convenience store. There, women refused any status as the objects of a consuming male gaze even as men assumed that role in a parody of tobe-looked-at-ness.7 In doing so, both were implicitly challenging the logic of binary gender and its particular structure of looking. That structure, defined by feminist theories of reading as the very heart of patriarchal narrative,8 has underpinned virtually all gender analysis in Thailand. T a o large degree, it also informs the currently dominant sedgender system in Thailand, but it has not always done so, and even now one cannot presume a totalized order in which binarity is completely hegemonic. Despite such historicity, however, Thai gender studies have described and reinforced a singular opposition between male and female. In general, the ethnography suggests a perfect, if differentially empowered, opposition between elemental principles such as hot and cold, high and low, strong and weak, closed and open, pure and polluting (with women occupying the latter position in these pairs).g A whole spectrum of similarly polarized terms can be extracted from ritual texts, and they have grounded most theorizations of Thai gender. T be sure, such idealizations have local currency and o considerable ideological force, but they are not universally accepted and they

Morris

Three Sexes and Four Sexualities

19

are not without counterpoint. Noting this all-too-neglected fact, Shigeharu Tanabe has recently called the normative bias of Thai ethnography into question and criticized the exclusive reliance on Buddhist texts, whose aim is the production of orthodoxy.10 However, where Tanabe attends to the internal subversion and contradictory elements of individual systems, I want also to consider the possibility of multiple systems and intersystemic contradiction. That is, I want to expand the notion of historical epoch beyond that of the disciplinary regime to accommodate competing ideologies, each internally heterogeneous but determined and circumscribed by distinct technologies of the self and the social order. The first gesture in this argument is the move away from history as a rationalizing principle. As Eve Sedgwick argues, we need to relinquish the narrative of rupture that has sustained the discourse on sexuality.12 Sedgwick herself claims that issues of modern homo/heterosexual definition are structured, not by the supersession of one model and the consequent withering away of another, but instead by the relations enabled by the unrationalized coexistence of different models during the times that they do coexist.13 T h e present appears to be one of those times in Thailand when different and mutually irreconcilable systems cohabit in a single social field.

The System o Three f

Although the first and historically prior system has gone through innumerable historical transformations, its logic is basically tripartite, with the terms of sexual identity being phuuchai (male), phuuying (female), and kathoey (transvestite/transsexual/hermaphrodite). Perhaps inevitably, it is the fact of a third term that attracts the Western dualists eye. The plethora of translations usually offered for kathoey really reflects a paucity of concepts for the biologically irreducible third category implied here. It has clearly meant different things at different times, but in one of its oldest formulations, that of Lan Na origin myths, it seems to have been neither male nor female, but both: a coherent identity attached to diverse and fluid practices. For the modern Western sensibility, for which sexual identity is construed in the idiom of consumption, as a function of object choice14 and of

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

20

practice defined in those terms, this combination of fixed subjectivity and multiple subject positions may appear as a contradiction. However, it is not contradictory in the traditional Thai context, where a division of public and private realms both permits and sustains such antitheses. Indeed, the crucial element in the Thai system of three seems to be a division in which sexual and gender identity is conceived as a repertoire of public appearances and behaviors that is quite independent of the various subject positions and sexual practices available within the private realm. T h e evidence for such claims is admittedly sparse and uneven, but the historical record provides at least a few suggestive texts. T h e first of these is the recently available Pathamamulamuli,l5 a translation of a palm-leaf manuscript that relates the origin of the universe and of Lan Na humanity as it was reportedly told by the Buddha. In its textual form, the work was probably composed by a monk, but it draws upon several popular stories which circulated in oral form among the Tai of the Shan states,16 the Khoen of Laos, the people of northeast Thailand (known locally as Isaan), and the Muang of Lan Na Thai (generally identified with northern Thailand and Chiang Mai). Its original sources may actually predate the arrival of Theravada Buddhism from Sri Lanka. In the Puthamamulamuli, the universe emerges from nonbeing through the intermingling of cold and hot air, these being dimensions of nothingness as well as the principles of inactivity and activity, respectively. Shortly thereafter, a female being, Nang Itthang Gaiya Sangkasi, emerges from the earth. Later, a male being named Pu Sangaiya Sangkasi is born of fire. Together, they populate the world, and from the four elements-earth, fire, water, and wind- they conjure three sexes: female, hermaphrodite, and male.17 Although it emerges from a context of binarity, the sexual trinity is central and fundamental to the origin of humanity. Indeed, humanity is correlate with triadic logic in the Pathamamulamuli. T h e interpretation of the sexual trinity is, of course, problematic, the more so because the text provides no description of the various sexes. T h e hermaphrodite fades in and out of the narrative, coupling with both the female and the male, and is referred to as both father and mother by the children of their unions. In some instances, she/he is jealous of the affections between the male and female.18 In others, he/she suffers neglect. Yet, while the pain and the

Morris

Three Sexes and Four Sexualities

21

pathos of the hermaphrodites position seem to be a function of herlhis existential condition, it is never suggested that he/she should or could be otherwise. Nor is there a discourse that impugns hidher moral integrity. In stereotypically Buddhist terms, the Pathamamulamuli attributes to every sex and gender a particular form of suffering (Pali, dukkha):men with the dissatisfaction that comes from unfulfilled physical desire, women with the agonies of childbirth and the loss of children, hermaphrodites with the emotional discomforts that visit the too-sensitive heart. For reasons that are never specified in the text, the hermaphrodite disappears from the Pathamamulamuli fairly early, but hidher form is echoed in other scenes of generation and other aspects of human existence. In chapter 3, for example, the origin of language is discussed in similar terms: The consonants are combined with vowels to form words of three genders: the feminine, the masculine and the neuter.19 In this context, I think the image of tripartite gender entails more than abstract fantasy. Although it expresses the idealizations of the mythic order, it presents identity as something that is highly elastic and subject to ideological manipulation. But if ideologies and regimes of naming change over time, language also retains the memory of previous usage.20 An analysis of the kathoey category can therefore reveal much about the history of changing social formations in Thailand. Indeed, the dialogic confrontation between the language of the Pathamamulamuli and the languages of its descendants and the contemporary biologized sedgender system occurs most visibly in that term. On the surface, the hermaphrodite of the Pathamamulamuli parallels that of premodern Europe. It, too, can appear as an interstitial gender occupying the liminal space between the idealized poles of male and female. However, this vision of transitivity implies a primary binarity in whose terms the kathoey must always be understood- as mediation, ambiguity, or intentional subversion. But this binarity is absent in the Pathamamulamuli. In that text, the hermaphrodite does not undermine oppositions between male and female but constitutes the third point in a triad in which there can be no single antithesis. Nor can the hermaphrodite be seen as a secondary identity. Rather, it possesses the same ontological status as the male and female characters. He/she is not merely a point of articulation, as is the cross-dresser in some theories of the modern West.21 He/she is

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

22

substantial, possesses an identity, is a self-same self. In this regard, the kathoey of the Pathamamulamuli is something of a conundrum for the articulation theorists (Butler and Garber most notable among them),22 who insist that it is performativity itself which grounds the possibility for escape from binarity and the heterosexual contract. What the Thai system of three points out, in fact, is that the theory of gender as performance is as historically and culturally relative-and relevant-as is the gender system of which it speaks; its implicit flight from biological essentialism may even shore up the absolutist claims for genetic and morphological duality. T h e system of three in Thailand is, on the other hand, an essential one in which all three sexes are of equal materiality. It is, of course, unlikely that there ever existed a period in accord with the completely triadic vision of the Pathamamulamuli. However, what texts we do have suggest a tradition of sexual and gendered identities incompatible with Western binarism. That tradition often intrigued and offended the sensibilities of visiting foreigners. Take, for example, Anna Leonowenss selfrighteous account of the Siamese monarchs palace during the reign of King Mongkut ( I 860s): Within these walls lurked lately fugitives of every class, profligates from all quarters of the city, to whom discovery was death; but here their sanctuary was impenetrable. Here were women disguised as men, and men in the attire of women, hiding vice of every vileness and crime of every enormity,-at once the most disgusting, the most appalling, and the most unnatural that the heart of man has conceived.23 Carl Bock, an intrepid sojourner and amateur naturalist, exercised more restraint in his description of the lusus naturae of Chiang Mai when he remarked only that, in addition to numerous albinos, he heard of several hermaphrodites.24 Although Bocks account provides no translations for the term hermaphrodite, it is virtually certain that he was referring to kathoeys. However, the hermaphrodites of Templesand Elephants are not the originary characters of the Pathamamulamuli. By the time of his writing, the term tathoey referred exclusively to a category of maleness. It is not Bock, however, but Leonowens who forces us to recognize the differential history of male and female transgression. Leonowenss claim

Morris

Three Sexes

and Four Sexualities

23

that there were women cross-dressed as men as well as men crossdressed as women speaks across the years and now draws our attention to the odd silencing of female sexual expression in both popular and scholarly discourse about Thailand. Although her work must be read with caution, her remarks have been echoed and corroborated in a number of other accounts. From Kukrit Pramojs epic melodrama, Si Phaendin (Four reigns),25 to Bocks own reference to court Amazons, the figure of the female cross-dresser appears as a shadow figure in many renditions of latenineteenth-century Thailand. In them, she exists as a public secret and as an enigma but never as an object of discussion upon which the writers eye rests. Nor does she have the legitimacy that is conferred by naming. Unlike male cross-dressers, who were identified as kathoeys, female crossdressers had no special designation until quite recently, when borrowings from the English language created a taxonomy of female sexual deviance. Until then, womens assumptions of masculine roles and demeanors were not naturalized in the sense that they were for men, who could actually cross over into a third domain, becoming less cross-dressers than crossed dressers. It should be clear that I am speaking here of a world that straddles the Pathamamulamulis ideal vision of three sexes and a biologically grounded vision of two sexes-and four sexualities. This is not a transhistorical paradigm. And because of the radically different notions of body and personhood that define Thai and Western sedgender systems, it is not completely translatable. In contemporary North America, kathoeys would encompass both transsexuals and transvestites at the same time; born as men, they remake themselves in the image of women. Increasing numbers of kathoeys are taking advantage of hormonal and surgical procedures,26 but in general, self-construction remains a matter of repeated daily practice and is a habitual but inescapable dimension of identity. T h e Thai language provides an exquisite idiom for this process. The term used for presentation of self, or making oneself up in the English sense of dressing, is taeng tua, which can be translated quite literally as making or composing the body. Everyone, regardless of gender, makes their body up on a daily basis and in accordance with culturally defined norms of masculine and feminine appearance. However, it is a virtually

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

24

universal presumption (within Thailand) that kathoeys are the (literal) masters of feminine habillement, and I was once told that kathoey taeng tua phuuying dii kwaa phuuying (kathoeys compose a female body better than d o women). This superior knowledge of feminine fashion and comportment is usually understood according to a bourgeois or nostalgically aristocratic aesthetic. Often it takes the form of parody and excess, which is why, when discussing the convenience-store scene, I suggested that the costume and performance of kathoeys actually mock the to-belooked-at-ness of women. In so doing, they discredit womens abilities to perform that fantasy and undermine assumptions of a totalized male subjectivity. Perhaps the most important thing to understand in this (present) context is the fact that a kathoey is a kathoey with or without makeup. This kind of naturalized identity is made possible by a vision in which dressing is less a modification of the body than a public construction of the embodied self and the final moment in which potential is actualized. Men, women, and kathoeys all agree that this potential is preordained from birth. A young boy who is particularly graceful or delicate will be openly discussed by his parents and relatives as a future kathoey. There is room for error, of course, and not all effeminate males are or become kathoeys. However, there is never doubt in anyones mind that kathoey is a class of males. This singular trajectory is somewhat at odds with the tradition of the Pathamamulamuli and the dictionary definition of kathoey as any person who has the appearance of both male and female (phuu thii mii laksana 2 yaang thii trongkan khaam), a definition much more in line with that of the English hermaphrodite. Nonetheless, the prerogative of the naturalized cross-dresser is now a male one. For me, one of the crucial issues in understanding the history of sexual and gendered identities in Thailand has to do with the appropriation and naturalization of the kathoey category by the structures and institutions of maleness. I do not mean to hypothesize some originary state in which the tripartite dream of the Pathamamulamuli was lived as equality. However, the trinity of genders exists in the Thai tradition as an imaginary possibility, and neither the distribution nor the production of power within that realm is given. Hence, even without recourse to an impossibly retreating moment

Morris

Three Sexes and Four Sexualities

25

of first purity, the question of historical formation remains. As Julia Epstein and Kristina Straub remark (following Rubin), sedgender systems are historically and culturally specific arrogations of the human body for ideological purposes. In sedgender systems, physiology, anatomy, and body codes (clothing, cosmetics, behaviors, miens, affective and object choices) are taken over by institutions that use bodily difference to define and coerce gender id en t i ty.27 Insofar as the issue of kathoeys and masculine prerogative goes, then, we need to ask how sedgender systems in Thailand have organized the somatic economy in such a way as to render both female and male bodies as media of masculine subjectivities. I should perhaps point out here that the Thai language does differentiate between these bodies at the level of genitalia-as humans with penises and vagina$*-- but that this genital identity is not deemed adequate as a criterion of gendered identity within the system of three. In the contemporary world, a kathoey is a man who appropriates female form without becoming a woman and without ceasing to be a man. This is a system in which bodies exist less as the locus and origin of consciousness than as an iconic ground or symbolic potential, which is realized through everyday practices. To understand fully the degree to whichkathoeys actually usurp the female body in this sense requires that we understand a kind of personhood in which the body and the person are radically independent entities. Such is the legacy of Theravada Buddhism, whose cardinal concepts, impermanence (Pali, anicca; Thai, khwaam may thaawon) and karma (Thai, kam), come together in a doctrine of the transitoriness of form. In this schema, every being goes through countless rebirths as both males and females until reaching that level of the cosmos in which gender is no longer a dimension of form. In Theravada Buddhism, only the lowest levels of birth and rebirth are structured in gendered terms and everyone has the possibility of experiencing masculine and feminine forms in different lifetimes.29 T h e fact that the system of three has evolved to permit men-and only men- to cross gender lines within the confines of a single life is an ideological feat of profound significance. And it is only comprehensible within Thai patriarchy, which polices the boundaries of maleness while insisting upon access to femaleness and which constructs

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

26

the female body as relatively immutable. For this reason, and in opposition to most of the literature on gender bending, I think it is necessary to consider the possibility that contemporary &hoey identity is as much a form of male access to the female domain as it is a subversion of binary gender logic. If I have belabored the status and the nature of @thoey identity, it is not because I want to explain it away but because the third term acts as an aporia in the conceptual framework through which modern Western audiences generally apprehend sexual identities. As such, it is also an entry point for the understanding of systemic differences. Within the system of the third, it would not be mistaken to understand the categories of phuuying, phuuchui, and kathoey as kinds of sexual identity, but it would be wrong to assume that such sexual identity determines either sexual practice or object choice. This is a system of sexual and gendered identities, but it is not a system of hetero- and homosexualities. T h e binary opposition of sexualities and the assumption that sexual practice is the ground of identity are dimensions of the second sedgender system. Before moving to a consideration of the latter, though, one wants to ask after female transvestism, for, as I said earlier, there have been female cross-dressers in Thailand for at least two hundred years. Regrettably, there is too little evidence for historical analysis. Considering the extreme openness of female cross-dressing in contemporary Thailand, however, it seems likely that the silence surrounding earlier forms of alternate female sexual expression is a result of occlusion rather than ignorance or invisibility. In this regard, patriarchal narratives of both Thai and Western origin seem to have effaced any expression of female sexual identity that could not be subsumed under a reproductive mandate. Those narratives give voice to an ideology in which femaleness is so thoroughly naturalized as reproductive capacity that cross-dressing is not permitted to alter the sexual identity of a woman. Nonetheless, those same narratives do not imply a prohibition against female cross-dressing or, as shall be discussed below, homoerotic practice; they suggest only that femaleness- as reproductive capacitywas inviolable, irreversible, and unified. Only in the past few decades, with the emergence of sexualities defined in terms of object choice, has the category of woman itself been differentiated into categories of heterosexual and

Morris

Three Sexes and Four Sexualities

27

homosexual, with the latter being understood as a deviation from the natural telos of biologys female body. Thailand is unusual in that sexual practice has never been subject to jural control. Only recently has a moral discourse emerged concerned with preventing sexual deviance and dissuading people from the pursuit of homoerotic desire, but even this has yet to be enshrined in legislative form. Currently, the only sphere in which homoeroticism is explicitly and authoritatively eschewed is that of psychiatry, which employs earlier American and European categories of neurosis to define lesbianism as a form of dysfunction.30 However, parenting guides that warn against sexual and especially homoerotic desire in children have become increasingly popular since the I ~ ~ O and they reveal much about the shifting nature of the somatic S , economy in Thailand. Previously, a variety of sexual relations- including homoerotic ones- between kathoeys, men, and women seems to have been possible in a number of ritual and domestic contexts. These relations did not compromise or affect a persons social status so long as they did not impede a persons abilities to fulfill other social obligations. This is no longer always the case, and I want now to consider a system of sexuality in which desire and practice are externalized as identity and are subject to moral criticism as well as discipline.

Engendering Sexualities: The System of Four

It is often assumed that, in the history of Western sexualities, homosexuality emerged from the ashes of an ambiguous third category, whether conceived in transvestite or in androgynous terms. The rise of binary and biologized genders is traced to the early modern period, at which time the hermaphrodite became not merely. an ambiguous third category but an irritant in the systematic division and stabilization of binary gender identity. According to most Foucauldian histories of Western sexuality, both hermaphroditism and androgyny were problematized in new ways by the infant sciences of anatomy, physiology, and psychology.31 An identity that had previously existed with ontological integrity was recategorized as a misidentified male or female and became subject to reassignation by medical and legal authorities.32 Same-sex desire was actually conceived as a

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

28

betrayal of biology under the new system, which wanted to eliminate the categorical crisis implied by ambiguity. Given the abundant literature arguing that Thailands modernity has been an imitation of European modernity, it is tempting to impose a Foucauldian schema upon the Thai material. However, the contexts are not completely comparable. To begin with, the Thai situation is one in which hermaphroditic possibilities were appropriated by patriarchys institutions of maleness in the form of the kathoey. This is in stark contrast to the situation in Europe, where there was an increasing tendency to absorb the hermaphrodite into the figure of the deviant woman.33 Furthermore, as I have already argued, Thai hermaphroditism is not coextensive with cross-dressing in the Western sense. I t was not simply redesignated under a new regime of naming. Rather, it was mobilized to new and changing ends within an equally changing patriarchal construction of sexual and gendered identity. More important, the new sedgender system was not completely displaced by the previous one. Kathoeys, who are, for the Westerner, the most visible signifiers of the tripartite system, are a very real part of the contemporary social landscape in Thailand. Indeed, one of the most powerful indices of systemic coexistence is the fact that kathoeys are now as likely to be passing for gay men as for women, and they frequently move back and forth between these systems of identification on a daily basis. The newly emergent sedgender system is comprised of four sexualities and can best be understood as a set of nested and overlapping binarisms in which a hierarchically arranged and biologically located opposition between male and female grounds a secondary, but similarly unequal, opposition between heterosexuality and homosexuality. Like the system of the third, it is encompassed by a patriarchal logic. T h e system of four sexualities continues to construe the kathoey in a male idiom (as an extremely effeminate form of gay identity), but where the tripartite system permitted maleness in two modes, as masculinity and femininity, the system of sexualities renders both maleness and femaleness as natural identities which are either realized or transgressed in sexual practice. Sexual practice is then remarked in its relation to sexual identity and brought into the public domain through forms of surveillance that range from legislation to gossip. Homosexuality is now a widely available and widely deployed concept in

Morris

Three Sexes a n d Four Sexualities

29

Thailand. Discussions about gay men and lesbian women, about the politics of the personal, and about the sexual lives of prominent people are now a common part of public culture. Several major news magazines feature advice columns for gay readers; a subdivision of the pornographic industry caters to gay male clients; an enormous service industry tends to gay tourists; and a number of novels with gay protagonists have recently appeared on the commercial market. Technically, homosexuality is referred to as rak ruam phet, meaning love of the same gender, and it is distinguished from rak taang phet, meaning love between different genders, although this dictionary terminology is rarely used. More often than not, the language of homosexuality is English. There are, in fact, many levels on which one can legitimately argue that gay and lesbian identities are an importation from the West. Not the least of these is the fact that the first truly politicized gay community to arise in Thailand emerged in response to the AIDS crisis. The international sex trade has without question been a crucial but not exclusive factor in the spread of AIDS, but it has also been a factor in the dissemination of images and discourses about gay culture outside Thailand. While these representations often evoke a sense of relative oppression abroad, they have also contributed to the unification and integration of gay identities and communities in major metropolitan areas. Both focusing and ossifying identity, this new construction of subjectivity offers an ambiguous combination of collective power and vulnerability. Its recentness and its foreignness are both signaled in the vocabulary through which it is represented. The Thai language itself has great difficulty accommodating homosexuality and provides only a handful of descriptive terms, mostly from other languages, and even these are more properly a part of the system of three described above. Lakka phet, a rarely used expression borrowed from the Pali, denotes cross-dressing without implying hermaphroditism. Phuuying phraphet sorng, also of Pali derivation, literally translates as second category of women and is applied to male transvestites. Both of these terms are used to identify effeminate men, who may or may not be gay in the sense of object choice,34 but men who have exclusive sexual relations with other men and whose demeanor is classically masculine are called gay.

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

30

Women who like women (phuuying thii choop phuuying) are referred to by the terms thorn (from the English tomboy) and dii (good), which designate cross-dressing lesbians and non-cross-dressing lesbians, respectively. Sometimes used interchangeably with thorn, thut is a profoundly ironic appropriation from the American movie about a reluctant and emphatically heterosexual male transvestite named Tootsie. And thorn itself is used as a cover term for all lesbians. Compared to the already slender vocabulary for male homosexuality, there is an additional linguistic poverty surrounding lesbianism. Despite the considerable debate within Thailand regarding the relative status and acceptability of male and female homosexuality, there is a sense in which Thai lesbianism is both more suppressed and more reified in local discourse. In dominant representations, there is a general tendency to deny the transgressive dimensions of lesbianism by construing it as a form of friendship which, despite its supposedly dangerously sexual excesses, does not ultimately threaten a womans ability to fulfill her role in the heterosexual contract. Unlike gay male sex, which is legitimated by the term Z n sawaat (playing [with] lovers) as a full expression of romantic love, e lesbian sex is called Zen pheuan (playing [with] friends) and is often denigrated as the mere pursuit of physical pleasure (khwaarn ~ k )So, too, gay . male lovers can be accorded the term for heterosexual lovers, namelyfaan, but female lovers are rarely referred to in this manner. T h e corollary, of course, is that a womans sexual relations with other women will never be allowed to inhibit her fulfillment of other social obligations. Undoubtedly, the minimal and trivializing language of homoerotic desire between women is a product of that system (discussed above) in which womens sexual identities encompassed and tolerated the possibility of same-sex relations. In the modern context, however, homoeroticism between women can signify a more profoundly critical positioning of self. And such resistant subjectivity is often dealt with by the mainstream in terms of simple denial. Thus lesbianism is remarked as a threat precisely to the degree that it can veil itself as mere friendship and disappear from the bisected landscape of homo/heterosexuality. In addition, there is a rather elaborate popular discourse that plays on other fears of female sexual power, advocating against female homoerotic experience -and all extrareproductive erotic experience -on the grounds

Morris

Three Sexes and Four Sexuolities

31

that it will lead to genital deformation. This use of medicalized terror in the pursuit of normative heterosexuality is uniquely applied to women, male sexual desire being deemed natural and irresistible. Expressed in parenting guides and occasional (illustrated) newspaper stories about women with something approaching genital giantism,J5 this discourse manifests a profound anxiety about the corrupting potential of female sexual desire. As in its original (Oxford English Dictionary) usage, where tomboy referred less to a boyish girl than to a sexually aggressive woman and where the term was often used as a synonym for harlot, there is an assumption in Thailand (among both Thais and expatriates) that there are a disproportionate number of thorns among prostitutes. There is, to my knowledge, no evidence to sustain such a claim. However, the perceived relationship between prostitution and thornism raises additional issues. Today the term thom also suggests an aesthetic of boyishness, and in this layering of connotation, in which the supposedly masculine sexual aggression of the strumpet and the stereotypically masculine demeanor of the thorn come together, the term begins to suggest something of the anti-woman. Ironically, perhaps, given the association of thomism and prostitution, it seems that the simultaneous denial and remarking of thorns relates to the fact that they have no exchange value in the political and representational economies of heterosexuality. Thorns who are prostitutes indeed commodify their bodies and their sexual labor (or are commodified) within capitalist patriarchy, but their thomism remains outside the exchange system. And this capacity to resist enompassment renders such women a threat to other forms of officially sanctioned female subjectivity- which can and are continually circulated as objects of desire and consumption. Only those lesbians called dii, who enact the local aesthetic of femininity, are partially redeemed by their participation in the system of patriarchal consumption. Although the new sedgender system conflates sexual practice with social identity, the conventional idioms of identity mitigate against it. This is one of the primary points of differentiation and conflict between the systems of three sexes and four sexualities. In the earlier but persisting regime, gender identity was a matter of social form, behavior, and comportment. If heterosexual relations were assumed and required between men and women

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

32

(kathoeys were excluded from this mandate), there was nothing to prohibit other forms of erotic desire and experience. What we see here is the redefinition of sexual identity in the idiom of anatomical destiny and the emergence of a gendered identity that refers to patterns of sexual consumption. Now, as is commonly accepted, the biological paradigm has reproduction as its point of focus and measure of success, and it sustains capitalisms structure of production by naturalizing a unit of production as a unit of reproduction. In this regard, the concealment of sexual identity can provide a means of evading both the productive and reproductive burdens of the bio1ogicaVcapitalistsystem. For this reason, biological realism distrusts appearances and insists upon its right to determine identity through various technologies of privileged viewing. At the same time, however, it asks cosmetic appearances to manifest hidden identities. Distrust and repetition are, as Homi Bhabba so cogently points out, the twin dimensions of ~ t e r e o t y p y ; ~ ~ we endlessly remark that that which we fear will slip beyond the control of our gaze. And so, to the extent that the system of sexuality fears that sexual identity cannot be fully inscribed on the body, it demands that dress and comportment be constructed as the externalizations of identity. The effect is a conflation of private and public domains that is always on the verge of disintegration but that nonetheless legitimates the surveillance of the private on the grounds that it affects the public world. This shift is what Foucault describes as the rise of the body politic and the signal of a regime whose primary disciplinary technology is surveillance. By the traditional Thai logic of visibility and invisibility, however, virtually any act is acceptable if it neither injures another person nor offends others through inappropriate self-disclosure. As one of the countrys more prominent kathoeys remarked about being gay in Thailand, there is no problem . . . providing you dont ripple the surface calm.37 Yet the very notion of sexuality as conceived in the modern West dissolves the separation of private and public domains by bringing homoerotic desire into the public domain as identity. Accordingly, practices which threaten the structures of ideal or symbolic order, such as anal sex among men or nonpenetrative sex among women, are increasingly discussed and their practitioners increas-

Morris

I Three Sexes and Four Sexualities

33

ingly subject to condemnation. Similarly, visible transgressions, such as cross-dressing, have come to signify other kinds of sexual transgression, and they, too, are remarked in the public discourse about appropriate gender identities. Indeed, the discourses about cross-dressing provide some of the most revealing insights into the emerging system of binary identity and normative heterosexuality.

Sumptuary Laws and the Importation of Gender Aesthetics

In her provocative analysis of cross-dressing and Western culture, Marjorie Garber notes that sumptuary laws, whose original purpose was the protection of upper-class privilege and the restriction of upward mobility during the late medieval and early modern periods, effectively entrenched an aesthetic of binary gender difference.38 The legislation of appropriate dress, which crystallized ideally dualist visions of male and female appearance, also opened up the possibility for transgressive cross-dressing. The correlation between sumptuary legislation and the cultures of consumption reveals much about the history of modern social formations in Europe, though Garber does little to qualify her assertions in cultural or geopolitical terms, and a similar correlation can be found in Thai history. From the time of King Chulalongkorn ( 1868-I~IO), Thailands monarchs had been emulating the traditions of European courts and aristocracies. Its finest young students went abroad to study, and it was this new elite of Europeanized professionals that staged the first antimonarchical coup and demanded a share of power following years of increasing taxation and diminishing salaries. Phibun Songkhram came to power with their backing on a platform of modernization that included ethnic homogenization and a concomitant normalization of cultural form. Between 1938 and 1944, his administration enacted legislation that regulated matters of ethnic identification, dress, culinary etiquette, marital relations, and even domestic behavi0rs.3~ Rathaniyom X (decree number 10) required that men wear shirts and trousers and that women don skirts and blouses. Both men and women were to wear shoes and hats. Traditional clothing was discouraged, and even the matter of wearing underclothes was regulated. With the Phibun admin-

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

34

istration, Western dress, which had been a site of playful appropriation and self-reconstruction under King Chulalongkorn, became a locus of prescriptive gender formation. For the first time in Thai history (at least to my knowledge), dress became a means of signifying a binarized genital identity, and cross-dressing became illegal. I do not know if anyone was ever prosecuted for transgressing the gender codes of such fashion law during this period. It would be useful to examine the court records of the time, but there is no doubt that the legislation had impact through fear, gossip, and the more positive influence of successful Westernized Thai bureaucrats. Undoubtedly, there were informal codes long before the enactment of the rathaniyom. However, the criminalization of cross-dressing (which fell with Phibun in 1944) marks an important development in the history of Thailands sedgender system, and in its histrionic assertion of binarity, it signals a crisis of authority that seems to have been brought about by the competition between two irreconcilable but coexistent sedgender systems. Now, it seems to me that we can only understand this crisis in the context of Thai modernity, for sedgender systems are only one site of many in which the self is constituted as a subject. Not surprisingly, the same ambiguity infuses other areas of the social formation, and I want briefly to focus on the two domains most obviously related to the sedgender system, namely the political apparatus and representational culture.

Political Hermaphroditism?On the Ambiguity of Thai Modernity

T h e modern Thai polity is one in which both the material body of the king and the abstract body of society exist as axes of political organization and representation. Despite a coup in 1932 which rendered the monarchy constitutional, the physical presence of the king is a crucial element in Thailands national integration.40 To this day, the king makes regular tours throughout the country. O n these circumambulatory treks, he enacts the ideal of the peoples monarch in charitable deeds while also circulating his own charismatic presence through televised spectacles that bind Thai citizens in an act of collective and simultaneous looking. At the same time, however, there is a social body that is protected and nurtured by an elected government through legislation and various forms of coercion and disci-

Morris

Three Sexes and Four Sexualities

35

pline. This is the body whose health, integrity, and stability are guarded by regulations which, for example, require prostitutes to carry health cards, which criminalize narcotics, and which permit regular military coups dktat whose ostensible purpose is the protection of the public interest. The fact that a discourse on public health and on the body politic does not preclude a discourse of charismatic and embodied monarchical authority incites skepticism regarding the obstetric orientation of Foucaults genealogy. Indeed, what Foucault says of Western society, that the monarchical body was replaced by the fantasy of a social body in a moment of rupture (the French Revolution),4*seems untenable in modern Thailand. The definitive characteristic of the contemporary Thai polity seems to be its duality, its maintenance of two rhetorics of the body and two structures of looking. This duality cannot be evaded with reference to a transitional stage. Thailand exists in the nexus of transnational capitalist relations and information technologies that define the contemporary world. If its sociopolitical response to this placement differs from the responses of Western European or other Asian societies, we cannot simply dismiss it as premodern. T h e implications of a heterogeneously organized polity are of serious consequence for a theory of sexuality, because we have been taught to assume that the emergence of hetero- and homosexualities is the effect of a single power apparatus whose object and locus of investment is the medicalized body. O n some level, the whole history of modernity as Foucault imagines it is an abstract pursuit of unity in which individuals not only have been subjected to constant surveillance but have been made to internalize the inspecting gaze.42 Nowhere is this logic more perfectly enacted than in the Western discourses of sexuality, where the policing of practices and desires functions in two ways: to contain sexuality in terms that serve capitalist production (within the nuclear family) and actually to stimulate contrary desires and practices which will then summon and legitimate the disciplinary system. At the center of this argument is an assumption that the modern episteme is structured in and through a gaze which aspires to total vision. From carceral architecture to medical knowledge, it is the pursuit of a penetrating and panoptic vision that Foucault understands as the driving force of modern p0wer.~3 And it is only in this context that sexuality can be organized as a matter of truth in a realist language of visibility

positions 2:l

Spring 1994

36

and invisibility, disclosure and revelation. Biomedical practice emerges here as the vehicle for exposing hidden truths about an identity which is no longer limited to the performance of roles, or the fulfillment of social and aesthetic obligations, but which is now a telos of the body. T h e issue most pressing to students of other modernities and other sexualities must then be the status of the gaze. What happens if the rhetoric and the structure of looking are different in other modern contexts, or if parallel logics of visibility exist alongside the panoptic gaze of Western modernity? What happens in places, such as Thailand, where appearance is not reconciled with an assumed but hidden reality in all contexts? H o w does one speak about a regime in which the maintenance of form is a social imperative but where the invisible deed is still considered beyond jural control? And can we speak about a technology of panoptic vision when the relationship between the visible and the invisible is not exclusively understood in terms of internalization or externalization but is also, on occasion, rendered as separation, displacement, and even opposition? This is the situation that confronts the student of contemporary Thailand. Just as the coexistence of opposed governing structures defines the contemporary polity, so the coexistence of different visualities defines the political culture of contemporary Thailand. T h e traditional culture of manque, with its separation of public identity and private practice, is still manifest on a variety of levels. T h e ubiquitous and obligatory expression of deference, kraeng cai, is one notable instance. Kraeng cai is a term that denotes consideration of and appropriate respect to elders and positionally senior persons, but it also implies the presentation of a mask and the veiling of felt emotion through public displays of agreeability.44 This masking is not sublimation or repression in the Freudian sense. Kraeng cai has no pathological connotations for Thais but is, instead, the proper mode of social interaction. T h e concept of face reflects a similar Valorization of surfaces. T h e term naa means face, front, or, in some contexts, surface, but it also connotes honor and propriety. It implies something of the quality that inheres in the Anglo-North American term for image or reputation, and it is equally vulnerable to damage. In many respects, then, kraeng cai is the acknowledgment of someone elses face. To lose face as a result of inappro-

Morris

Three Sexes and Four Sexualities

37

priate disclosure or the disclosure of impropriety is a terrible thing in Thailand, terrible not merely for the person whose face is broken (taek) but for everyone concerned, because the universally acknowledged sanctity of the mask is violated in this moment. Until very recently, no one expected or assumed a relationship of identity between ones face and ones private self. Naa is not a representation of subjectivity but a presentation of public order. The discourse of sexuality clearly threatens this construction, but, as of yet, it remains as a powerful structure for the facilitation and containment of social interaction. In some respects, the culture of manque that is permitted by the concepts of kraeng cai and naa enables great mobility and fluidity of practice, preserving the rights of individuals to pursue whatever pleasures, desires, or fascinations they choose. Still operative in a number of contexts, this kind of separation is perfectly summed up in a story that appeared in a national newspaper some nine years ago. In November 1984, Thairat ran a story about a woman who lived as a man, fell in love with another woman, and then killed that womans husband when he withdrew his support for their union. The newspaper reported that, until the crime, the community was nonplussed by the relationship because the lesbian was friendly and helpful to her neighbours45 Her fulfillment of social obligations protected her from any criticism-not because it hid a truer identity which might then be negatively valued but because the enactment of social responsibilities constituted the only relevant dimension of her public identity. This story and that of the convenience store full of cross-dressers, as well as Prakits assertions of Thai liberality, would be understood as evidence of great tolerance in Western contexts. And yet this utopian vision rests uneasily for me. The image of mutual acceptance and celebratory difference is shaken by other images of alienation, violence, and dispossession. I am thinking, for example, of the time a gay male friend told me of his first self-disclosure to a high school friend and of how he was beaten in the wake of his confession. I am thinking also of a thorn friend who was forced to separate from her lover of five years when that woman left to tend ailing parents in the country. T h e women agreed to the separation with great grief and reluctance because they were afraid of the villagers, whom they

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

38

feared would attack them. Both of these friends are in their late twenties, and both identify themselves as homosexual, asguy and thorn, respectively. They are part of a new generation for whom sexual identity is a matter not simply of public roles but also of sexual practice and object choice. And it is here, where identity is naturalized and subject to increasing probes as well as increasing regulation, that homosexuality per se exists.

Conclusions: Not a Genealogy of Morals

At this point, I want to repeat my earlier disclaimer about the artificial linearity of argumentation. I have constructed an image of historical transformation and perhaps even of rupture, in which an earlier system of tripartite sex has given way to one of binary sex and four sexualities. However, this is not a fully rationalized process, and the emergence of modern sexualities has not completely eliminated earlier sexes. Nor is this coexistence simply the function of that residual memory which inheres in words. It is a dimension of the total social fabric, and it has enormous consequences for the kinds of identity structures and personal choices that any individual can inhabit. For the corollary of a nonspatialized but nonetheless structural pluralism is that individuals move back and forth between ideological regimes and discursive formations. This is not merely a movement between different subject positions (as the more banal versions of postmodernism argue). Rather, it is a movement between different kinds of subjectivity. Individuals actually inhabit and negotiate different complexes of personal identity: different arrangements and understandings of the relationships between sex, gender, and sexuality. It is not only kathoeys, who, as I have said, now pass as gay men or women depending on context, but also men and women who cross the boundaries of sedgender systems and present themselves as simply men or women or kathoeys in some cases and as heterosexual or homosexual men and women in other cases. In the end, it might be simpler if one could carry out an investigation of Thai sexualities by simply forgetting Foucault.46 But, Baudrillards witty polemic aside, no one writing about sexuality can forget Foucault. At best we can willfully ignore him. And we are left with a burden of profound ethno-

Morris

Three Sexes and Four Sexualities

39

centrism.47 We know that the apparatus of power is different in every society and that the discourses of sex and gender differ from context to context. Yet a considerable body of critical theory persists in a mode of historical analysis- the emphatically linear genealogy- that derives from the Wests specific experience of modernity. And because it assumes that transnational capitalism is a process of encompassment and homogenization, neither the uniformity of modernity nor the structure of its emergence is questioned. In theories that seek rationality as the sole index of modernity, the crossdresser, the androgyne, and the hermaphrodite appear as self-evident confrontations with the assumed orthodoxy of binarity. In this process, the only alternative to binary (heterosexual) logic is ironically contained by itas opposition and as ambivalence. Nor is the attempt to render sexual or gender ambiguity in the idiom of articulation or performance, when maleness and femaleness themselves remain entrapped by anatomy, an adequate alternative to biological reductionism. Perhaps, in the end, what Thailand tells us is that the essentialism of the two can only be overcome with an essentialism of three-or more. Perhaps it tells us that the limits of our genders are simply the limits of our language. It most certainly tells us that heterogeneity is the point at which analysis either achieves lucidity or becomes an agent of occlusion and domination. This includes not merely the heterogeneity within the traditions of Western Europe but also the heterogeneity that emerges in other cultures and in the interstitial spaces and mutually encompassing relations between them.

Notes

My thanks to Yukiko Hanawa and Penny van Esterik for editorial advice and critical input.

I would also like to acknowledge the critical comments and suggestions of external readers, as well as those of Jean Comaroff and Peter A. Jackson. Only some of these suggestions

could be incorporated here, but all of them inspired me to think about the issues of this essay with greater care. Finally, I would like to dedicate this paper to R.B. and to my Thai friends who are living with courage in difficult times. By modern Buddhism, I mean the period following King Mongkuts reforms, these being oriented toward philosophical and bureaucratic rationalization. See Charles F. Keyes, Buddhist Politics and Their Revolutionary Origins in Thailand, International Political Science Thomas A. Kirsch, Modernizing Implications of 19thReview 10, no. 2 (1989): 121-142;

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

40

Century Reforms in the Thai Sangha, in Religion and the Legitimation o Power in Thailand, f

Laos, and Burma, ed. Bardwell L. Smith (Chambersburg, Pa.: Anima, 1973), 52-65; and

Stanley J. Tambiah, World Conqueror and World Renouncer: A Study o Buddhism and Polity in f

Thailand against a Historical Backdrop (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, I 976).

2

Nan Goldin, The Other Side (New York: Scalo, 1993).

3 Goldins book, written in English, is clearly intended for a North American audience, although the image of Thai femininity has a capacity to signify and invoke desire in ways

that exceed the binary terms of Orientalism. T h e fetishism of Thai beauty in other Asian, particularly Japanese, contexts suggests an image system that is far more complex than can be contained by the logic of Orientalism.

4 I used the term sexlgender system as it is developed by Gayle Rubin in T h e Traffic of Women: Notes on the Political Economy of Sex, in Toward an Anthropology o Women, ed. f Rayna R. Reiter (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1975). 157-210. 5 Many kathoeys who are not employed in the sex trade or the burlesque scene resent being

depicted in terms that are exclusive to them.

6 See Shelly Errington, Recasting Sex, Gender, and Power: A Theoretical Overview, in Power and Drference: Gender in Island Southeast Asia, ed. Jane Monnig Atkinson and Shelly Errington (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1990), 1-58.

7 O n the concept of to-be-looked-at, see Laura Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Screen 16, no. 3 (1975): 6-18. T h e parodic dimension here derives from the fact that

men dressed as women were soliciting the glance of other men dressed as women. 8 T h e binary logic of the structurally male gaze in patriarchal reading formations is by now well established in feminist criticism. T h e classic statements appear in Laura Mulveys germinal essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, and in Teresa de Lauretiss Desire in Narrative, in Alice Doesnt: Feminism, Semiotics, Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984), 103-157.

f 9 See, for example, Richard Davis, Muang Metaphysics: A Study o Northern Thai Myth and Ritual (Bangkok: Pandora, 1984);Charles F. Keyes, Mother or Mistress but Never a Monk: Buddhist Notions of Female Gender in Rural Thailand, American Ethnologist I I (1984): 223-241; Thomas A. Kirsch, Buddhism, Sex Roles, and Thai Society, in Women o Southf east Asia, ed. Penny van Esterik, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Occasional Paper no. 9 (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University, 1982), 16-41; and Penny van Esterik, Lay Women in Theravada Buddhism, in van Esterik, Women o Southeast Asia, 55-78. f Shigeharu Tanabe, Spirits, Power, and the Discourse of Female Gender: T h e Phi Meng 10 Cult of Northern Thailand, in Thai Constructions o Knowledge, ed. Manas Chitakasem and f Andrew Turton (London: SOAS, 1991), 184. Also see Paul T. Cohen and Gehan Wijeyewarf dene, Spirit Cults and the Position o Women in Thailand, special issue of Mankind 14, no. 4 (1984).Charles F. Keyes addresses male gender and ambiguity in Ambiguous Gender: Male Initiation in a Northern Thai Buddhist Society, in Gender and Religion: On the Complexity o f

Morris

I Three Sexes and

Four Sexualities

41

I2

Symbolr, ed. Caroline Walker Bynum, Stevan Harrell, and Paula Richman (Boston: Beacon Press, 1986),66496. Here I rely heavily on Foucaults later work. See Michel Foucault, PowerlKnowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977, ed. Colin Gordon (New York: Pantheon, 1980). See also Technologies o the S e y A Seminar with Michel Foucault, ed. Luther H. Marf tin, Huck Gutman, and Patrick H. Hutton (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988). Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology o the Closet (Berkeley: University of California Press, f

3 4 5

16

7

18

20

99445-46. Ibid., 47. Ibid., 8. Anatole-Roger Peltier, ed. and trans., Pathamamulamuli: The Origin of the World in the Lan Nu Tradition (Bangkok: Suriwong Books, 1991),186-187. The word Tai refers to a language group that includes peoples of Laos, Thailand, Southwestern China, and parts of Vietnam. It is to be distinguished from the word Thai, which means free and which refers to the people of the Thai state. Peltier, Pathamamulamuli, 191-203. I use he/she in this context to suggest the Thai gender-neutral pronouns khao and man. However, the English hybrid construction evokes liminality more than neutrality, and readers should bear this in mind. I do not in any way mean to suggest that kathoey identity is a compromise, but I can think of no other way to represent the Thai phenomenon. Peltier, Pathamamulamuli, 236. It is worth noting in this context that personal pronouns in Thai are also of three kinds, and that it is both possible and normal to use nondifferentiating pronouns in the third person. Second-person pronouns do not specify gender, and there are also neutral first-person pronouns. In situations of extreme intimacy between differently gendered speakers, men and women may even adopt the first-person pronouns of the opposite gender. Mikhail Bakhtin, Discourse in the Novel, in The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, ed. Michael Holquist, trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981),2 5 ~ 4 2 2 . Marjorie Garber, Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing and Cultural Anxiety (New York: Routledge,

1992), I I Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion o Identity (New York: Routf ledge, 1990);Garber, Vested Znterests. f 23 Anna Leonowens, The Engltjh Governess at the Siamese Court: Being Recolkctions o Six Years in the Royal Palace at Bangkok, unauthorized reprint of the original edition (London: Triibner, 1870). Carl Bock, Temples and Elephants: The Narrative o a Journey o Exploration through Upper f f 24 Siam andLao (1884; reprint, Bangkok: White Orchard, 1985), 320.

22

positions 2: 1

Spring 1994

42

25 According to the transliteration protocols followed until now, Kukrits name would be written Khukhrit Pramoj, and the novel, Sii Phaendin. However, I have used the spelling of the published text, Si Phaendin, vols. I and 2, trans. Tulachandra (Bangkok: Duang Kamol, I 98 I). 26 Interestingly, such medical metamorphosis is not specifically or even primarily concerned with genitalia. More common are operations to remove ribs, to modify and attenuate the shoulders, or to construct breasts. Electrolysis is also common. 27 Julia Epstein and Kristina Straub, Body Guards (New York: Routledge, I&), 3. 28 Penny van Esterik, Nurturance and Reciprocity in Thai Studies: A Tribute to Lucien and Jane Hanks, Thai Studies ProjecdWomen in Development Consortium in Thailand, Working Paper no. 8 (Toronto: York University, 1992), 13. 29 Ibid., 1 0 - 1 2 . 30 Walter Irvine, The Thai-Yuan Madman, and the Modernizing, Developing Thai Nation as Bounded Entities under Threat: A Study in the Replication of a Single Image (Ph.D. diss., University of London, 1982). f 3 Michel Foucault, History o Sexuality, trans. R. Hurley (New York: Pantheon, 1978). 32 There is surely no more moving testimony to the agonies that accompanied such transitions than that contained in Michel Foucaults Herculine Barbin: Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs o a Nineteenth-Century French Hermaphrodite (New York: Random House, 1980). f 33 Ann Rosalind Jones and Peter Stallybrass, Fetishizing Gender: Constructing the Hermaphrodite in Renaissance Europe, in Epstein and Straub, Body Guards, 90. 34 Peter Jackson, Mule Homosexuality in Thailand (Amsterdam: Global Academic Publishers, I989), 2 1 . 35 T h e term used to refer to women with enlarged genitalia is norng yai, which translates as big little sister. In 1991, the national newspaper, Thairat, ran a series of stories about a young prostitute who was discovered to be a norngyui. T h e girl was arrested for solicitation. In the prurient representation of her body, which was carried out in full-color photographs provided by the police, it often appeared that her crime was a physiological deformity. 36 Homi K. Bhabha, The Other Question: T h e Stereotype and Colonial Discourse, Screen 24, no. 6 (1983): 18-36. 37 Prakit Tu Vacharesinthu, cited in Bangkok Post, 16 February 1992,37. 38 Garber, Vested Interests, 21-23. 39 Kobkua Suwannathat-Pian, Phibunsongkhrams Socio-Cultural Programme and the Siamese Malay Response, in Proceedings o the Fourth International Conference on Thai Studf ies (Kunming: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1990), 1 4 9 1 5 0 .For a translation of the Thai edicts, see T h a k Chaloemtiara, Thai Politics, I932-I957 (Bangkok: Social Science Association of Thailand, 1978). 40 O n the topic of national integration, see Charles F. Keyes, Buddhism and National Integration in Thailand, Journal o f h i a n Studies 30, no. 3 (1971):419-429; and Stanley J. Tam-

Morris

I Three

Sexes and Four Sexualities

43

biah, The Buddhist Saints o the Forest and the Cult o Amulets (Cambridge: Cambridge Unif f versity Press, 1984).

41 Foucault, PowerlKnowledge, 55-62; Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth o the f Prison, trans. A. Sheridan (New York: Pantheon, 1977). 42 Foucault, PowerlKnowledge, 155.

f 43 See also Jonathon Crary, Techniques o the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, MIT Press, 1990).

f 44 Niels Mulder, Inside Thai Society: An Interpretation o Everyday Llfe (Bangkok: Duang Kamol, 1990),97-99, I O ~ I II . See also Barton Sensenig, Self-Concept and Achievement in Northern Thailand (Ph.D. diss., Cornell University, 1977).

45 Thairat, 25 November 1984, cited in Jackson, Male Homosexuality, I 15. 46 My invocation of Jean Baudrillards Forget Foucault (New York: Semiotext[e], 1987) is intended to be evocative and perhaps expedient rather than facetious. I hope there is no offense. 47 For a major critique of Foucaults Eurocentrism, see Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Can the Subaltern Speak? in Marxism and the Interpretation o Culture, ed. Cary Nelson and f Lawrence Grossberg (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988),271-313.

Вам также может понравиться

- Origins of Thai Massage in Reusi Dat TonДокумент8 страницOrigins of Thai Massage in Reusi Dat TonJacklynlim LkcОценок пока нет

- Childbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory and Childbirth Attitudes Questionner Thai LanguageДокумент11 страницChildbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory and Childbirth Attitudes Questionner Thai LanguageWenny Indah Purnama Eka SariОценок пока нет

- An Analysis of Cultural Substitution in English To Thai TranslationДокумент16 страницAn Analysis of Cultural Substitution in English To Thai TranslationMizuno MichiruОценок пока нет

- Efficacy of Clinacanthus Nutans Extracts in PatientsДокумент7 страницEfficacy of Clinacanthus Nutans Extracts in Patientsconrad9richterОценок пока нет

- All About #1 - The Top 5 Reasons To Study Thai - Lesson Notes PDFДокумент3 страницыAll About #1 - The Top 5 Reasons To Study Thai - Lesson Notes PDFMatthewVincentОценок пока нет

- Idiom Attack Vol. 1 - Everyday Living (Trad. Chinese Edition) : 成語攻擊 1 - 日常生活: Idiom Attack, #1От EverandIdiom Attack Vol. 1 - Everyday Living (Trad. Chinese Edition) : 成語攻擊 1 - 日常生活: Idiom Attack, #1Оценок пока нет

- Cantonese OmniglotДокумент8 страницCantonese OmniglotKarelBRGОценок пока нет

- Japanese Mnemonics For CharactersДокумент15 страницJapanese Mnemonics For Characterstumblrwush_contactОценок пока нет

- Newspeak From The Recent Attacks: Art of War, Sun-Tzu, Chapter 1, Paragraph 18Документ4 страницыNewspeak From The Recent Attacks: Art of War, Sun-Tzu, Chapter 1, Paragraph 18Christopher RhudyОценок пока нет

- Price Dynamics of Crude OilДокумент3 страницыPrice Dynamics of Crude OilnitroglyssОценок пока нет

- Mohochikuan Tome7Документ83 страницыMohochikuan Tome7proutmanseedsОценок пока нет

- Performance Appraisal ReportДокумент36 страницPerformance Appraisal ReportVishal SharmaОценок пока нет

- Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. LTD.: Buddhism and Buddhist Studies Checklist/Order FormДокумент17 страницMunshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. LTD.: Buddhism and Buddhist Studies Checklist/Order Formsachintiwary100% (1)

- Moringa Anti Asthma Activity PDFДокумент8 страницMoringa Anti Asthma Activity PDFCisco SilvaОценок пока нет

- Abhidhamma Notes ExplainedДокумент30 страницAbhidhamma Notes ExplainedChandima SrimaliОценок пока нет

- A History of The Thet Maha Chat and Its PDFДокумент250 страницA History of The Thet Maha Chat and Its PDFoodyjookОценок пока нет

- The Signification of Naga in Thai Architectural and Sculptural OrnamentsДокумент19 страницThe Signification of Naga in Thai Architectural and Sculptural OrnamentsmrohaizatОценок пока нет

- Tipitaka: Suttasaar: Vol. 1 Digha Nikaya & Majjhima Nikaya (Hindi)Документ230 страницTipitaka: Suttasaar: Vol. 1 Digha Nikaya & Majjhima Nikaya (Hindi)Singh1430100% (2)

- 3 Character Classic CantoneseДокумент39 страниц3 Character Classic Cantonesecoconutty100% (1)

- Dificultate 3 AДокумент23 страницыDificultate 3 AJohn JohnОценок пока нет

- The Fig and Olive MiracleДокумент2 страницыThe Fig and Olive MiracleIman Syafar100% (1)

- Cantonese PhrasesДокумент2 страницыCantonese Phrasesyagnamoid_21Оценок пока нет

- TAME L25 062014 Tpod101 PDFДокумент5 страницTAME L25 062014 Tpod101 PDFRobbyReyesОценок пока нет

- HOA3 - Assignment #1 - The Relgions of IndiaДокумент9 страницHOA3 - Assignment #1 - The Relgions of IndiaRojun AranasОценок пока нет

- Review ArticleДокумент19 страницReview ArticleAssaf FeldmanОценок пока нет

- Color VisionДокумент8 страницColor Visionpastuso1Оценок пока нет

- Notes On AbhiDhamma Analysis PDFДокумент922 страницыNotes On AbhiDhamma Analysis PDFအသွ်င္ ေကသရ100% (1)

- Thai History PDFДокумент80 страницThai History PDFJakgrid JainokОценок пока нет

- 6 Dharma GatesДокумент5 страниц6 Dharma Gatesgurdjieff100% (1)

- A Brief Herbal Guide For Dr. Namgyal Tenzin For The Traditional Tibetan Medicine CourseДокумент2 страницыA Brief Herbal Guide For Dr. Namgyal Tenzin For The Traditional Tibetan Medicine Courseab21423Оценок пока нет

- Thai Food & Culture: What Is The Food Like?Документ2 страницыThai Food & Culture: What Is The Food Like?Khuyen NguyenОценок пока нет

- Class Struggles in ChinaДокумент236 страницClass Struggles in ChinaRed Star LibraryОценок пока нет

- Gate Control Theory ExplainedДокумент4 страницыGate Control Theory ExplainedrelbuhmОценок пока нет

- NAN-CHING Chapter Four:: On Illnesses, Cont'dДокумент8 страницNAN-CHING Chapter Four:: On Illnesses, Cont'dJohn JohnОценок пока нет

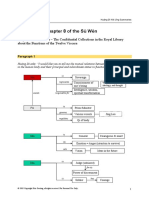

- Summary of Chapter 8 of The Sù WènДокумент4 страницыSummary of Chapter 8 of The Sù WènBudiHoОценок пока нет

- Tai Chi Qigong Shibashi: Instruction ManualДокумент20 страницTai Chi Qigong Shibashi: Instruction ManualMaxoid115Оценок пока нет

- Business Communication in ThailandДокумент34 страницыBusiness Communication in ThailandPrashant DhayalОценок пока нет

- Tai Chi Chuan Self DefenseДокумент50 страницTai Chi Chuan Self Defenseswetor100% (1)

- International Centre For Eye Health Teaching Set 2 The Eye in Primary Health CareДокумент25 страницInternational Centre For Eye Health Teaching Set 2 The Eye in Primary Health Carejo_jo_maniaОценок пока нет

- Mizo Conference Tawh...Документ2 страницыMizo Conference Tawh...zomisda100% (1)

- 促脈 Cu Mai Abrupt Skipping HastyДокумент3 страницы促脈 Cu Mai Abrupt Skipping HastyEthan KimОценок пока нет

- Danh Mục Tổng Hợp Sách Tiếng ViệtДокумент373 страницыDanh Mục Tổng Hợp Sách Tiếng ViệtKhanh Trần VTОценок пока нет

- Concise for document 001 on types of charityДокумент195 страницConcise for document 001 on types of charityChandan Paul100% (1)

- The Art of AttentionДокумент35 страницThe Art of AttentionMihai EnacheОценок пока нет

- Empathy and Human ExperienceДокумент25 страницEmpathy and Human ExperienceCesar CantaruttiОценок пока нет

- Closing Movement 3 - Massaging The Dantian - Proofread LN 2021-05-28Документ1 страницаClosing Movement 3 - Massaging The Dantian - Proofread LN 2021-05-28api-268467409Оценок пока нет

- Palm Oil Waste Potential in Indonesia 2020-2030Документ10 страницPalm Oil Waste Potential in Indonesia 2020-2030Putrika 02Оценок пока нет

- Small Step PosturesДокумент6 страницSmall Step PosturesHarpreet PablaОценок пока нет

- A Vedic Grammar For Students, Including A Chapter On Syntax and Three Appendixes List of Verbs, Metre, Accent (1916) BWДокумент528 страницA Vedic Grammar For Students, Including A Chapter On Syntax and Three Appendixes List of Verbs, Metre, Accent (1916) BWjilyliuОценок пока нет

- Major thigh muscles and their attachments, innervation, and actionsДокумент2 страницыMajor thigh muscles and their attachments, innervation, and actionsanon_281423826Оценок пока нет

- The Glymphatic System - A Beginner's GuideДокумент27 страницThe Glymphatic System - A Beginner's GuidejayjonbeachОценок пока нет

- Speak Mandarin in Five Hundred WordsДокумент237 страницSpeak Mandarin in Five Hundred Words褚佩昕100% (1)

- Chinese Modern (Xiaobing Tang)Документ399 страницChinese Modern (Xiaobing Tang)morgado_dacostaОценок пока нет

- Thesis Body - What Is Thai CuisineДокумент110 страницThesis Body - What Is Thai CuisineMandeep Singh67% (3)

- Super Creativity - Tony BuzanДокумент16 страницSuper Creativity - Tony BuzanHenrik Sundgren0% (1)

- Of Woman Born Motherhood As Experience AДокумент4 страницыOf Woman Born Motherhood As Experience AAntonio MОценок пока нет

- Queering PlatoДокумент29 страницQueering Platochri1753100% (1)