Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Aggabao Vs Parulan Digest

Загружено:

April SaligumbaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Aggabao Vs Parulan Digest

Загружено:

April SaligumbaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

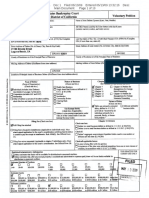

G.R. No.

165803

September 1, 2010

SPOUSES REX AND CONCEPCION AGGABAO, Petitioners, vs. DIONISIO Z. PARULAN, JR. and MA. ELENA PARULAN, Respondents. BERSAMIN, J.: FACTS: Subject of this case are 2 parcels of land located, BF Homes, Paraaque City and registered under TCT No. 633763 and TCT No. 633774 in the name of respondents Spouses Maria Elena A. Parulan (Ma. Elena) and Dionisio Z. Parulan, Jr. (Dionisio), who have been estranged from one another. Real estate broker Marta K. Atanacio (Atanacio) offered the property to the petitioners, who initially did not show interest due to the rundown condition of the improvements, but Atanacios persistence prevailed. On February 2, 1991, they and Atanacio met with Ma. Elena at the site of the property thelatter showed to them the following documents: (a) the owners original copy of TCT No. 63376; (b) a certified true copy of TCT No. 63377; (c) three tax declarations; and (d) a copy of the SPA dated January 7, 1991 executed by Dionisio authorizing Ma. Elena to sell the property.On the same day, they paid P20,000.00 as earnest money, Ma. Elena then executed a handwritten Receipt of Earnest Money, and stipulated that: (a) they would pay an additional payment of P130,000.00 on February 4, 1991; (b) they would pay the balance of the bank loan of the respondents amounting to P650,000.00 on or before February 15, 1991; and (c) they would make the final payment of P700,000.00 once Ma. Elena turned over the property on March 31, 1991. On February 4, 1991, the petitioners went to the Office of the Register of Deeds and the Assessors Office to verify the TCTs in the company of Atanacio and her husband (also a licensed broker). There, they discovered that the lot under TCT No. 63376 had been encumbered to Banco Filipino in 1983 or 1984, but that the encumbrance had already been cancelled due to the full payment of the obligation. They noticed that the Banco Filipino loan had been effected through an SPA executed by Dionisio in favor of Ma. Elena. They found on TCT No. 63377 the annotation of an existing mortgage in favor of the Los Baos Rural Bank, also effected through an SPA executed by Dionisio in favor of Ma. Elena, coupled with a copy of a court order authorizing Ma. Elena to mortgage the lot to secure a loan of P500,000.00. The petitioners and Atanacio next inquired about the mortgage and the court order annotated on TCT No. 63377 at the Los Baos Rural Bank. There, they met with Atty. Noel Zarate, the banks legal counsel, who related that the bank had asked for the court order because the lot involved was conjugal property. Following their verification, the petitioners delivered P130,000.00 as additional down payment on February 4, 1991; and P650,000.00 to the Los Baos Rural Bank on February 12, 1991, which then released the owners duplicate copy of TCT No. 63377 to them. On March 18, 1991, the petitioners delivered the final amount of P700,000.00 to Ma. Elena, who executed a deed of absolute sale in their favor.However, Ma. Elena did not turn over the owners duplicate copy of TCT No. 63376, claiming that said copy was in the possession of a relative who was then in Hongkong. She assured them that the owners duplicate copy of TCT No. 63376 would be turned over after a week. On March 19, 1991, TCT No. 63377 was cancelled and a new one was issued in the name of the petitioners. Ma. Elena did not turn over the duplicate owners copy of TCT No. 63376 as promised. In due time, the petitioners learned that the duplicate owners copy of TCT No. 63376 had been all along in the custody of

Atty. Jeremy Z. Parulan, who appeared to hold an SPA executed by his brother Dionisio authorizing him to sell both lots. At Atanacios instance, the petitioners met on March 25, 1991 with Atty. Parulan, they were also accompanied by one Atty. Olandesca. They recalled that Atty. Parulan smugly demanded P800,000.00 in exchange for the duplicate owners copy of TCT No. 63376, because Atty. Parulan represented the current value of the property to be P1.5 million. As a counter-offer, however, they tendered P250,000.00, which Atty. Parulan declined, giving them only until April 5, 1991 to decide. Hearing nothing more from the petitioners, Atty. Parulan decided to call them on April 5, 1991, but they informed him that they had already fully paid to Ma. Elena. Thus, on April 15, 1991, Dionisio, through Atty. Parulan, commenced an action praying for the declaration of the nullity of the deed of absolute sale executed by Ma. Elena, and the cancellation of the title issued to the petitioners by virtue thereof.In turn, the petitioners filed on July 12, 1991 their own action for specific performance with damages against the respondents.Both cases were consolidated for trial and judgment in the RTC. RTC ruled in favour of Plaintiff Parulan and declared the sale covered by TCT 63376 and 63377 as null and void. RTC declared that the SPA in the hands of Ma. Elena was a forgery, based on its finding that Dionisio had been out of the country at the time of the execution of the SPA; that NBI Sr. Document Examiner Rhoda B. Flores had certified that the signature appearing on the SPA purporting to be that of Dionisio and the set of standard sample signatures of Dionisio had not been written by one and the same person;22 and that Record Officer III Eliseo O. Terenco and Clerk of Court Jesus P. Maningas of the Manila RTC had issued a certification to the effect that Atty. Alfred Datingaling, the Notary Public who had notarized the SPA, had not been included in the list of Notaries Public in Manila for the year 1990-1991. CA affirmed the decision of the RTC.Hence, the instant petition. Issues 1) Which between Article 173 of the Civil Code and Article 124 of the Family Code should apply to the sale of the conjugal property executed without the consent of Dionisio? 2) whether or not they had diligently inquired into the authority of Ma. Elena to convey the property, not whether or not the TCT had been valid and authentic, as to which there was no doubt. Held: The petition has no merit. We sustain the CA. Article 124, Family Code, applies to sale of conjugal properties made after the effectivity of the Family Code The sale was made on March 18, 1991, or after August 3, 1988, the effectivity of the Family Code. The proper law to apply is, therefore, Article 124 of the Family Code, for it is settled that any alienation or encumbrance of conjugal property made during the effectivity of the Family Code is governed by Article 124 of the Family Code. Article 124 of the Family Code provides: Article 124. The administration and enjoyment of the conjugal partnership property shall belong to both spouses jointly. In case of disagreement, the husbands decision shall prevail, subject to recourse to the court by the wife for proper remedy, which must be availed of within five years from the date of the contract implementing such decision.

In the event that one spouse is incapacitated or otherwise unable to participate in the administration of the conjugal properties, the other spouse may assume sole powers of administration. These powers do not include disposition or encumbrance without authority of the court or the written consent of the other spouse. In the absence of such authority or consent, the disposition or encumbrance shall be void. However, the transaction shall be construed as a continuing offer on the part of the consenting spouse and the third person, and may be perfected as a binding contract upon the acceptance by the other spouse or authorization by the court before the offer is withdrawn by either or both offerors. The power of administration does not include acts of disposition or encumbrance, which are acts of strict ownership. As such, an authority to dispose cannot proceed from an authority to administer, and vice versa, for the two powers may only be exercised by an agent by following the provisions on agency of the Civil Code (from Article 1876 to Article 1878). Specifically, the apparent authority of Atty. Parulan, being a special agency, was limited to the sale of the property in question, and did not include or extend to the power to administer the property. The petitioners insistence that Atty. Parulans making of a counter-offer during the March 25, 1991 meeting ratified the sale merits no consideration. Under Article 124 of the Family Code, the transaction executed sans the written consent of Dionisio or the proper court order was void; hence, ratification did not occur, for a void contract could not be ratified. The void sale was a continuing offer from the petitioners and Ma. Elena that Dionisio had the option of accepting or rejecting before the offer was withdrawn by either or both Ma. Elena and the petitioners. The last sentence of the second paragraph of Article 124 of the Family Code makes this clear, stating that in the absence of the other spouses consent, the transaction should be construed as a continuing offer on the part of the consenting spouse and the third person, and may be perfected as a binding contract upon the acceptance by the other spouse or upon authorization by the court before the offer is withdrawn by either or both offerors. Due diligence required in verifying not only vendors title, but also agents authority to sell the property Article 124 of the Family Code categorically requires the consent of both spouses before the conjugal property may be disposed of by sale, mortgage, or other modes of disposition. In Bautista v. Silva,the Court erected a standard to determine the good faith of the buyers dealing with A seller who had title to and possession of the land but whose capacity to sell was restricted, in that the consent of the other spouse was required before the conveyance, declaring that in order to prove good faith in such a situation, the buyers must show that they inquired not only into the title of the seller but also into the sellers capacity to sell. Thus, the buyers of conjugal property must observe two kinds of requisite diligence, namely: (a) the diligence in verifying the validity of the title covering the property; and (b) the diligence in inquiring into the authority of the transacting spouse to sell conjugal property in behalf of the other spouse. It is true that a buyer of registered land needs only to show that he has relied on the face of the certificate of title to the property, for he is not required to explore beyond what the certificate indicates on its face.In this respect, the petitioners sufficiently proved that they had checked on the authenticity of TCT No. 63376 and TCT No. 63377 with the Office of the Register of Deeds in Pasay City as the custodian of the land records; and that they had also gone to the Los Baos Rural Bank to inquire about the mortgage annotated on TCT No. 63377. Thereby, the petitioners observed the requisite diligence in examining the validity of the TCTs concerned. Yet, it ought to be plain enough to the petitioners that the issue was whether or not they had diligently inquired into the authority of Ma. Elena to convey the property, not whether or not the TCT had been valid and authentic, as to which there was no doubt. Thus, we cannot side with them.

Firstly, the petitioners knew fully well that the law demanded the written consent of Dionisio to the sale, but yet they did not present evidence to show that they had made inquiries into the circumstances behind the execution of the SPA purportedly executed by Dionisio in favor of Ma. Elena. Had they made the appropriate inquiries, and not simply accepted the SPA for what it represented on its face, they would have uncovered soon enough that the respondents had been estranged from each other and were under de facto separation, and that they probably held conflicting interests that would negate the existence of an agency between them. To lift this doubt, they must, of necessity, further inquire into the SPA of Ma. Elena. Indeed, an unquestioning reliance by the petitioners on Ma. Elenas SPA without first taking precautions to verify its authenticity was not a prudent buyers move.40 They should have done everything within their means and power to ascertain whether the SPA had been genuine and authentic. If they did not investigate on the relations of the respondents vis--vis each other, they could have done other things towards the same end, like attempting to locate the notary public who had notarized the SPA, or checked with the RTC in Manila to confirm the authority of Notary Public Atty. Datingaling. It turned out that Atty. Datingaling was not authorized to act as a Notary Public for Manila during the period 1990-1991, which was a fact that they could easily discover with a modicum of zeal. Secondly, the final payment of P700,000.00 even without the owners duplicate copy of the TCT No. 63376 being handed to them by Ma. Elena indicated a revealing lack of precaution on the part of the petitioners. It is true that she promised to produce and deliver the owners copy within a week because her relative having custody of it had gone to Hongkong, but their passivity in such an essential matter was puzzling light of their earlier alacrity in immediately and diligently validating the TCTs to the extent of inquiring at the Los Baos Rural Bank about the annotated mortgage. Yet, they could have rightly withheld the final payment of the balance. That they did not do so reflected their lack of due care in dealing with Ma. Elena. Lastly, another reason rendered the petitioners good faith incredible. They did not take immediate action against Ma. Elena upon discovering that the owners original copy of TCT No. 63376 was in the possession of Atty. Parulan, contrary to Elenas representation. Human experience would have impelled them to exert every effort to proceed against Ma. Elena, including demanding the return of the substantial amounts paid to her. But they seemed not to mind her inability to produce the TCT, and, instead, they contented themselves with meeting with Atty. Parulan to negotiate for the possible turnover of the TCT to them.

Вам также может понравиться

- Advanced Players Guide ErrataДокумент5 страницAdvanced Players Guide Erratadanschul100% (1)

- DN Script ThumbelinaДокумент9 страницDN Script ThumbelinaMaria Andreina MontañezОценок пока нет

- Banat V ComelecДокумент3 страницыBanat V ComelecPNP MayoyaoОценок пока нет

- Warrant of Arrest SampleДокумент1 страницаWarrant of Arrest SampleApril Saligumba57% (7)

- Nera Vs Rimando: G.R. L-5971 February 27, 1911 Ponente: Carson, J.Документ4 страницыNera Vs Rimando: G.R. L-5971 February 27, 1911 Ponente: Carson, J.Lyndon OliverosОценок пока нет

- Showing That The Defendants Are About To DepartДокумент3 страницыShowing That The Defendants Are About To DepartBoy Kakak TokiОценок пока нет

- Montaño V VercelesДокумент2 страницыMontaño V VercelesFrancis Masiglat100% (1)

- Tanada vs. AngaraДокумент2 страницыTanada vs. AngaraApril SaligumbaОценок пока нет

- Huma Rights Course SyllabusДокумент7 страницHuma Rights Course SyllabusSheina GeeОценок пока нет

- Warrant of ArrestДокумент2 страницыWarrant of ArrestApril Saligumba100% (3)

- Salient Features of Notarial LawДокумент3 страницыSalient Features of Notarial LawPaolo JavierОценок пока нет

- Module Vi. Special Groups of Employees Libres V NLRCДокумент29 страницModule Vi. Special Groups of Employees Libres V NLRCYuri NishimiyaОценок пока нет

- Declaration of Presumptive Death Strict Standard Under Art 41Документ12 страницDeclaration of Presumptive Death Strict Standard Under Art 41Onireblabas Yor OsicranОценок пока нет

- Special Power of Attorney (SPA, HQP-HLF-064, V02)Документ2 страницыSpecial Power of Attorney (SPA, HQP-HLF-064, V02)Rpadc CauayanОценок пока нет

- Vitto Vs CAДокумент2 страницыVitto Vs CAKym Buena-RegadoОценок пока нет

- Rule 130, Section 40, (One of The Execptions To The Hearsay Rule) ProvidesДокумент2 страницыRule 130, Section 40, (One of The Execptions To The Hearsay Rule) ProvidesVon Lee De LunaОценок пока нет

- University of The Philippines College of Law: Sienes v. EsparciaДокумент2 страницыUniversity of The Philippines College of Law: Sienes v. EsparciaMaribel Nicole LopezОценок пока нет

- BARQS1Документ2 страницыBARQS1Charles CalicaОценок пока нет

- Acts: It Is Averred That at The Time: RespondentДокумент4 страницыActs: It Is Averred That at The Time: RespondentCarina Amor ClaveriaОценок пока нет

- in Re Estate of The Deceased Gregorio Tolentino - WillsДокумент2 страницыin Re Estate of The Deceased Gregorio Tolentino - WillsAndrea TiuОценок пока нет

- Inheritance Proposal 1Документ1 страницаInheritance Proposal 1Wïñ ÑërОценок пока нет

- Crim Pro Case DigestednessДокумент21 страницаCrim Pro Case DigestednessStephen Neil Casta�oОценок пока нет

- 1.b. Digest ALVARICO vs. SOLA GR 138953 - Bob20110376 PDFДокумент3 страницы1.b. Digest ALVARICO vs. SOLA GR 138953 - Bob20110376 PDFcontessa_butronОценок пока нет

- Hilario v. Intermediate Appellate CourtДокумент2 страницыHilario v. Intermediate Appellate CourtzacОценок пока нет

- Ortigas-Co-vs-Feati-Bank-DigestДокумент2 страницыOrtigas-Co-vs-Feati-Bank-DigestBea DiloyОценок пока нет

- BELGICA V OCHOAДокумент6 страницBELGICA V OCHOABea Crisostomo100% (1)

- DNV Ru Ou 0102Документ144 страницыDNV Ru Ou 0102arjunprasannan7Оценок пока нет

- Noceda Vs EscobarДокумент2 страницыNoceda Vs EscobarKar EnОценок пока нет

- 3-T PP Vs AcostaДокумент2 страницы3-T PP Vs AcostaShaine Aira ArellanoОценок пока нет

- Philippine Airlines, Inc., Petitioner, VS., National Labor Relations Commission, Ferdinand PINEDA and GODOFREDO CABLING, RespondentsДокумент48 страницPhilippine Airlines, Inc., Petitioner, VS., National Labor Relations Commission, Ferdinand PINEDA and GODOFREDO CABLING, RespondentsJohn Lester LantinОценок пока нет

- Pacis vs. Morales - EscanoДокумент2 страницыPacis vs. Morales - EscanoJovelan V. EscañoОценок пока нет

- Reyes V RTC & ZenithДокумент2 страницыReyes V RTC & ZenithJean Mary AutoОценок пока нет

- Exconde v. CapunoДокумент2 страницыExconde v. CapunoJovy Balangue MacadaegОценок пока нет

- People V BreisДокумент11 страницPeople V BreisCharlene Salazar AcostaОценок пока нет

- Quiao v. QuiaoДокумент3 страницыQuiao v. QuiaoAKОценок пока нет

- AFP-RSBS vs. RP, G.R. 180086, July 2, 2014Документ2 страницыAFP-RSBS vs. RP, G.R. 180086, July 2, 2014Ron Christian EupeñaОценок пока нет

- Agrarian Law & Social Legislation: Case Digest - Lance MorilloДокумент4 страницыAgrarian Law & Social Legislation: Case Digest - Lance MorilloLance MorilloОценок пока нет

- Honasan vs. Panel of Investigating ProsecutorsДокумент1 страницаHonasan vs. Panel of Investigating Prosecutorsiceiceice023Оценок пока нет

- Labstan AssignmentДокумент47 страницLabstan Assignmentjade123_129Оценок пока нет

- Domingo v. Domingo, 42 SCRA 131Документ8 страницDomingo v. Domingo, 42 SCRA 131Cza PeñaОценок пока нет

- Partnership 1810-1814Документ14 страницPartnership 1810-1814Michelle ValeОценок пока нет

- 12 Chapter 4Документ22 страницы12 Chapter 4Sushrut Shekhar100% (2)

- 19 Molina y Salvador Vs de La RivaДокумент2 страницы19 Molina y Salvador Vs de La RivaVina CagampangОценок пока нет

- San Vicente CaseДокумент1 страницаSan Vicente Casedj_quilatesОценок пока нет

- Torts Cases: I. Fe Cayao vs. Ramolete FactsДокумент16 страницTorts Cases: I. Fe Cayao vs. Ramolete FactsJana GonzalezОценок пока нет

- Ramos V PangilinanДокумент2 страницыRamos V PangilinanAllen Windel BernabeОценок пока нет

- SALES LAW TranscriptДокумент3 страницыSALES LAW Transcriptjstin_jstinОценок пока нет

- NOEL Vs CAДокумент5 страницNOEL Vs CAPhoebe MascariñasОценок пока нет

- Retention Limit (Section 6) : Direct and Exclusive Public Purposes)Документ7 страницRetention Limit (Section 6) : Direct and Exclusive Public Purposes)Rafael Kieran MondayОценок пока нет

- AgencyДокумент27 страницAgencyParina SharmaОценок пока нет

- Regner v. Logarta (CivPro - Summons)Документ3 страницыRegner v. Logarta (CivPro - Summons)Cathy AlcantaraОценок пока нет

- Article 36 of The Vienna Convention On Consular Relations - A Sear PDFДокумент50 страницArticle 36 of The Vienna Convention On Consular Relations - A Sear PDFv.pandian PandianОценок пока нет

- CJVH Civrev2Документ118 страницCJVH Civrev2Leroj HernandezОценок пока нет

- Court Determines Who Has Better Right To PropertyДокумент2 страницыCourt Determines Who Has Better Right To Propertyyurets929Оценок пока нет

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Frederick Garfield Waite Solicitor-General HarveyДокумент4 страницыPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Defendant-Appellant Frederick Garfield Waite Solicitor-General HarveyJustineОценок пока нет

- R.A. No. 9262 Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004Документ10 страницR.A. No. 9262 Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004Francis LeoОценок пока нет

- Doctrine: People v. CaseyДокумент17 страницDoctrine: People v. CaseyBea Czarina NavarroОценок пока нет

- DBP Vs CapulongДокумент2 страницыDBP Vs CapulongRepolyo Ket CabbageОценок пока нет

- The United States vs. Ignacio CarlosДокумент8 страницThe United States vs. Ignacio CarlosJayzell Mae FloresОценок пока нет

- Maralit Case DigestДокумент1 страницаMaralit Case DigestKim Andaya-YapОценок пока нет

- Abella V AbellaДокумент3 страницыAbella V AbellaRamon EldonoОценок пока нет

- Vicar International Corp vs. Feb Leasing Case DigestДокумент3 страницыVicar International Corp vs. Feb Leasing Case Digestkikhay11Оценок пока нет

- Spouses Luciana and Pedro Dalida V CA DigestДокумент1 страницаSpouses Luciana and Pedro Dalida V CA DigestArmand Jerome Carada100% (1)

- Case DigestДокумент9 страницCase DigestOCP Santiago CityОценок пока нет

- 11) SSSEA v. CAДокумент1 страница11) SSSEA v. CAMonicaCelineCaroОценок пока нет

- Ceferino Padua v. RanadaДокумент3 страницыCeferino Padua v. RanadaKent A. AlonzoОценок пока нет

- Succession Notes 2Документ4 страницыSuccession Notes 2Anthony Tamayosa Del AyreОценок пока нет

- Acap vs. CAДокумент7 страницAcap vs. CACrisDBОценок пока нет

- Natalia Realty vs. DAR, GR. 103302, August 12, 1993Документ5 страницNatalia Realty vs. DAR, GR. 103302, August 12, 1993pennelope lausanОценок пока нет

- Civil Law Reviewer Cases IIIДокумент82 страницыCivil Law Reviewer Cases IIICrnc NavidadОценок пока нет

- Aggabao V ParulanДокумент8 страницAggabao V ParulanArnaldo DomingoОценок пока нет

- Jollibee Popeye - Google SearchДокумент1 страницаJollibee Popeye - Google SearchApril SaligumbaОценок пока нет

- Upon Compliance With These Requirements, The Issuance of A Writ of Possession Becomes MinisterialДокумент12 страницUpon Compliance With These Requirements, The Issuance of A Writ of Possession Becomes MinisterialApril SaligumbaОценок пока нет

- WolverineДокумент2 страницыWolverineApril SaligumbaОценок пока нет

- FileДокумент1 страницаFileApril SaligumbaОценок пока нет

- LontokДокумент1 страницаLontokApril SaligumbaОценок пока нет

- Affirmative Defenses KanssogdefДокумент4 страницыAffirmative Defenses KanssogdefRicharnellia-RichieRichBattiest-CollinsОценок пока нет

- Form No GJS1Документ6 страницForm No GJS1NIKHIL SWAMY B C0% (1)

- Bond To Be Signed by Parent and The Gentlemen Selected For Initial Training With A View To Being Commissioned in The Regular ArmyДокумент5 страницBond To Be Signed by Parent and The Gentlemen Selected For Initial Training With A View To Being Commissioned in The Regular ArmySonu LovesforuОценок пока нет

- Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima YojanaДокумент2 страницыPradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima YojanaRavindra ParmarОценок пока нет

- Grievance Filing and Reporting FormДокумент5 страницGrievance Filing and Reporting FormtsegayeОценок пока нет

- Claw Assignment NewestДокумент6 страницClaw Assignment NewestclaraОценок пока нет

- Evacuee Property and Displaced Personslaws Repeal Act 1975Документ3 страницыEvacuee Property and Displaced Personslaws Repeal Act 1975Haseeb HassanОценок пока нет

- Federal Marine Terminals v. Worcester Peat Co.: Charter PartiesДокумент4 страницыFederal Marine Terminals v. Worcester Peat Co.: Charter PartiesLarz MozoОценок пока нет

- Loss of ChanceДокумент5 страницLoss of ChanceThePoitiersОценок пока нет

- Lesaca V LesacaДокумент4 страницыLesaca V LesacaQueenie SabladaОценок пока нет

- Classes of Partnership ch6Документ26 страницClasses of Partnership ch6astra fishОценок пока нет

- Litigation ParalegalДокумент2 страницыLitigation Paralegalapi-78177266Оценок пока нет

- Official Opinions of The Compliance Board 1 (2010) : Joseph H. PotterДокумент4 страницыOfficial Opinions of The Compliance Board 1 (2010) : Joseph H. PotterCraig O'DonnellОценок пока нет

- Dlpcastle InstДокумент41 страницаDlpcastle InstWilliam LiuОценок пока нет

- St. Michael School v. Masaito DevtДокумент12 страницSt. Michael School v. Masaito DevtJobi BryantОценок пока нет

- Summary of The Paris Convention For The Protection of Industrial Property (1883)Документ4 страницыSummary of The Paris Convention For The Protection of Industrial Property (1883)Rabelais Medina100% (1)

- J/lfark Pasnak D/B / A MJP Investment Trust: Property Tax Purchase LetterДокумент2 страницыJ/lfark Pasnak D/B / A MJP Investment Trust: Property Tax Purchase LetterMichael D KaneОценок пока нет

- Workmens-Compensation Act 1923Документ18 страницWorkmens-Compensation Act 1923Shipra ShrivastavaОценок пока нет

- Peoria County Booking Sheet 04/19/15Документ10 страницPeoria County Booking Sheet 04/19/15Journal Star police documentsОценок пока нет

- Michael Nahass BK 8.09.Bk.14465.TA Doc 1Документ12 страницMichael Nahass BK 8.09.Bk.14465.TA Doc 1Fuzzy PandaОценок пока нет

- Zaki ResumeДокумент2 страницыZaki ResumebrukebarunОценок пока нет

- Igot Vs Valenzona PDFДокумент16 страницIgot Vs Valenzona PDFAwin LandichoОценок пока нет