Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Jlewin Vitrase Fun Facts March 2012

Загружено:

api-131514457Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Jlewin Vitrase Fun Facts March 2012

Загружено:

api-131514457Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

Vitrase Fun Facts: The role of the vitreous in diabetic retinopathy James Lewin, PharmD Postdoctoral Fellow/Vitrase Lead

The inspiration for this article came from an inquiry that I received in third month of my fellowship. I received an unsolicited request for medical information from a clinician regarding Vitrase (hyaluronidase injection) and the effect inducing posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). Although the lyophilized, ovine formulation of hyaluronidase (which is no longer being manufactured) was previously studied for the induction of PVD and the effect on progression of diabetic retinopathy, it was not FDAapproved for this use and ISTA is not conducting further studies in this population with the current formulation of Vitrase.1 The aim of this article is to describe the pathologic role of the vitreous gel in the development of diabetic retinopathy and to provide a brief overview of vitreolytic agents. This article does not represent a recommendation for the use of any of the pharmaceuticals or biologics named herein, and all opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of ISTA or its employees. The evolution of technology has facilitated much advancement in ocular imaging tools, such as ocular coherence tomography (OCT), and has enabled researchers to establish an association between disorders of the vitreous body and the development of diabetic retinopathy.2 As time progresses, the vitreous liquefies and eventually pulls away or separates from the back of the eye where it is attached to the retina. This process is called PVD and is a common event that can occur in all individuals at some point later on in their life. Studies have demonstrated a clear increase in the prevalence of PVD with age.3 In general, interventions are not required for PVD unless the vitreous does not separate clearly from the retina (incomplete PVD). Incomplete PVD is a surrogate marker for vitreomacular adhesion (VMA), which can manifest as many retinal and macular disorders including but not limited to macular hole, age-related macular degeneration, as well as diabetic and cystoid macular edema. Although vitrectomy has been established as an option for inducing PVD and correcting VMA, this surgical approach is not always reliable and can be very expensive; furthermore, the use of non-invasive interventions could potentially reduce patient exposure to severe surgical complications. Researchers are investigating vitreolytic agents to induce PVD through vitreous liquefaction (liquefactants), vitreoretinal separation (interfactants), or both. At this time, there are no FDA-approved agents for treating PVD or VMA See Table 1. Table 1: Classification of vitreolytics that have either been tested or are currently under development.ab Interfactants Liquefactants Both Mechanisms Enzymatic Dispase Hyaluronidase Ocriplasmin Collagenase tPA Nattokinase Chondrotinase Nonenzymatic RGD peptides Vitreosolve a 2 Adapted from Schneider, et al b Abbreviations: RGD= Arginine-glycine-aspartate; tPA=Tissue plasminogen activator The recent submission of a Biological License Application (BLA) subsequent to successful Phase III clinical trial results with Ocriplasmin a truncated form of the human serine protease plasmin was another reason for deeming this article appropriate for the MAM Newsletter. The original BLA was

submitted by Thrombogenics in December 2011 for the treatment of symptomatic VMA including macular hole: the FDA has granted Ocriplasmin priority review status, and, as a result, Thrombogenics has withdrawn their original filing and announced on February 2, 2012 that they plan to re-submit a BLA in April 2012 in order to meet the FDA pre-approval inspection timelines. References: 1. Kuppermann BD, Mercado HQ, Graue-Wiechers F, et al. Effect of Intravitreous Hyaluronidase (Vitrase) on Progression of Diabetic Retinopathy in Humans. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2002;43: EAbstract 3865. Accessed March 2, 2012. 2. Schneider EW, Johnson MW. Emerging nonsurgical methods for the treatment of vitreomacular adhesion: a review. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011:5;1151-1165 3. Ang A, Poulson AV, Snead DRJ, et al. Posterior Vitreous Detachment: Current Concepts and Management. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/513226. Published September 27, 2005. Accessed March 1, 2012 4. ThromboGenics NV. ThromboGenics Announces that the FDA Intends to Grant Ocriplasmin Priority Review. ThromboGenics website. http://thrombogenics.com/wpcontent/uploads/2011/03/THR_02_Ocriplasmin-BLA-PriorityReview_Final_ENG.pdf. Published February 2, 2012. Accessed March 1, 2012

Вам также может понравиться

- Jameslewin CVДокумент3 страницыJameslewin CVapi-131514457Оценок пока нет

- Lewin JB - 2012 Postersession Dia-MedcommworkshopДокумент1 страницаLewin JB - 2012 Postersession Dia-Medcommworkshopapi-131514457Оценок пока нет

- Jameslewinabstract Dia Medcomm Workshop 2012Документ1 страницаJameslewinabstract Dia Medcomm Workshop 2012api-131514457Оценок пока нет

- Vitrase Fun Facts January 2012Документ2 страницыVitrase Fun Facts January 2012api-131514457Оценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Foundry Technology GuideДокумент34 страницыFoundry Technology GuidePranav Pandey100% (1)

- Expose Anglais TelephoneДокумент6 страницExpose Anglais TelephoneAlexis SoméОценок пока нет

- Monitoring Tool in ScienceДокумент10 страницMonitoring Tool in ScienceCatherine RenanteОценок пока нет

- Costing - Type Wise Practical Mcq-Executive-RevisionДокумент71 страницаCosting - Type Wise Practical Mcq-Executive-RevisionShruthi ParameshwaranОценок пока нет

- Book 7 More R-Controlled-VowelsДокумент180 страницBook 7 More R-Controlled-VowelsPolly Mark100% (1)

- Basics of Duct DesignДокумент2 страницыBasics of Duct DesignRiza BahrullohОценок пока нет

- Rev F AvantaPure Logix 268 Owners Manual 3-31-09Документ46 страницRev F AvantaPure Logix 268 Owners Manual 3-31-09intermountainwaterОценок пока нет

- Surveying 2 Practical 3Документ15 страницSurveying 2 Practical 3Huzefa AliОценок пока нет

- Module 2 What It Means To Be AI FirstДокумент85 страницModule 2 What It Means To Be AI FirstSantiago Ariel Bustos YagueОценок пока нет

- Principal Component Analysis of Protein DynamicsДокумент5 страницPrincipal Component Analysis of Protein DynamicsmnstnОценок пока нет

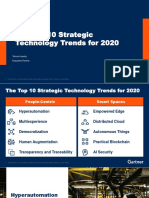

- The Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends For 2020: Tomas Huseby Executive PartnerДокумент31 страницаThe Top 10 Strategic Technology Trends For 2020: Tomas Huseby Executive PartnerCarlos Stuars Echeandia CastilloОценок пока нет

- Minimum Fees To Be Taken by CAДокумент8 страницMinimum Fees To Be Taken by CACA Sanjay BhatiaОценок пока нет

- CGL Flame - Proof - MotorsДокумент15 страницCGL Flame - Proof - MotorspriteshОценок пока нет

- Carbapenamses in Antibiotic ResistanceДокумент53 страницыCarbapenamses in Antibiotic Resistancetummalapalli venkateswara raoОценок пока нет

- 1 20《经济学家》读译参考Документ62 страницы1 20《经济学家》读译参考xinying94Оценок пока нет

- Ejemplo FFT Con ArduinoДокумент2 страницыEjemplo FFT Con ArduinoAns Shel Cardenas YllanesОценок пока нет

- SIO 12 Syllabus 17Документ3 страницыSIO 12 Syllabus 17Paul RobaiaОценок пока нет

- SSNДокумент1 377 страницSSNBrymo Suarez100% (9)

- Solidwork Flow Simulation TutorialДокумент298 страницSolidwork Flow Simulation TutorialMilad Ah100% (8)

- 2019 ASME Section V ChangesДокумент61 страница2019 ASME Section V Changesmanisami7036100% (4)

- Hotels Cost ModelДокумент6 страницHotels Cost ModelThilini SumithrarachchiОценок пока нет

- Roll Covering Letter LathiaДокумент6 страницRoll Covering Letter LathiaPankaj PandeyОценок пока нет

- Siegfried Kracauer - Photography (1927)Документ17 страницSiegfried Kracauer - Photography (1927)Paul NadeauОценок пока нет

- 1 Univalent Functions The Elementary Theory 2018Документ12 страниц1 Univalent Functions The Elementary Theory 2018smpopadeОценок пока нет

- Beyond B2 English CourseДокумент1 страницаBeyond B2 English Coursecarlitos_coolОценок пока нет

- After EffectsДокумент56 страницAfter EffectsRodrigo ArgentoОценок пока нет

- Sales Account Manager (Building Construction Segment) - Hilti UAEДокумент2 страницыSales Account Manager (Building Construction Segment) - Hilti UAESomar KarimОценок пока нет

- KG ResearchДокумент257 страницKG ResearchMuhammad HusseinОценок пока нет

- AWK and SED Command Examples in LinuxДокумент2 страницыAWK and SED Command Examples in Linuximranpathan22Оценок пока нет

- MP & MC Module-4Документ72 страницыMP & MC Module-4jeezОценок пока нет