Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Tesellation

Загружено:

Desai RameshИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Tesellation

Загружено:

Desai RameshАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

A tessellation of pavement

A honeycomb is an example of a tessellated natural structure A tessellation or tiling of the plane is a pattern of plane figures that fills the plane with no overlaps and no gaps. One may also speak of tessellations of parts of the plane or of other surfaces. Generalizations to higher dimensions are also possible. Tessellations frequently appeared in the art of M. C. Escher, who was inspired by studying the Moorish use of symmetry in the Alhambra tiles during a visit in 1922. Tessellations are seen throughout art history, from ancient architecture to modern art. In Latin, tessella is a small cubical piece of clay, stone or glass used to make mosaics.[1] The word "tessella" means "small square" (from "tessera", square, which in its turn is from the Greek word for "four"). It corresponds with the everyday term tiling which refers to applications of tessellations, often made of glazed clay.

Contents

[hide]

1 Wallpaper groups 2 Tessellations and color 3 Tessellations with quadrilaterals 4 Regular and semi-regular tessellations 5 Self-dual tessellations 6 Tessellations and computer models 7 Tessellations in nature 8 Number of sides of a polygon versus number of sides at a vertex 9 Tessellations of other spaces 10 See also 11 Notes 12 References

[edit] Wallpaper groups

Tilings with translational symmetry can be categorized by wallpaper groups, of which 17 exist.[2] All seventeen of these groups are represented in the Alhambra palace in Granada, Spain. Of the three regular tilings two are in the p6m and one is in p4m.

[edit] Tessellations and color

If this parallelogram pattern is colored before tiling it over a plane, seven colors are required to ensure each complete parallelogram has a consistent color that is distinct from that of adjacent areas. (This tiling can be compared to the surface of a torus.) Coloring after tiling, only four colors are needed. When discussing a tiling that is displayed in colors, to avoid ambiguity one needs to specify whether the colors are part of the tiling or just part of its illustration. See also symmetry. The four color theorem states that for every tessellation of a normal Euclidean plane, with a set of four available colors, each tile can be colored in one color such that no tiles of equal color meet at a curve of positive length. Note that the coloring guaranteed by the four-color theorem will not in general respect the symmetries of the tessellation. To produce a coloring which does, as many as seven colors may be needed, as in the picture at right.

[edit] Tessellations with quadrilaterals

Copies of an arbitrary quadrilateral can form a tessellation with 2-fold rotational centers at the midpoints of all sides, and translational symmetry whose basis vectors are the diagonal of the quadrilateral or, equivalently, one of these and the sum or difference of the two. For an

asymmetric quadrilateral this tiling belongs to wallpaper group p2. As fundamental domain we have the quadrilateral. Equivalently, we can construct a parallelogram subtended by a minimal set of translation vectors, starting from a rotational center. We can divide this by one diagonal, and take one half (a triangle) as fundamental domain. Such a triangle has the same area as the quadrilateral and can be constructed from it by cutting and pasting.

[edit] Regular and semi-regular tessellations

Hexagonal tessellation of a floor A regular tessellation is a highly symmetric tessellation made up of congruent regular polygons. Only three regular tessellations exist: those made up of equilateral triangles, squares, or hexagons. A semiregular tessellation uses a variety of regular polygons; there are eight of these. The arrangement of polygons at every vertex point is identical. An edge-toedge tessellation is even less regular: the only requirement is that adjacent tiles only share full sides, i.e. no tile shares a partial side with any other tile. Other types of tessellations exist, depending on types of figures and types of pattern. There are regular versus irregular, periodic versus aperiodic, symmetric versus asymmetric, and fractal tessellations, as well as other classifications. Penrose tilings using two different polygons are the most famous example of tessellations that create aperiodic patterns. They belong to a general class of aperiodic tilings that can be constructed out of self-replicating sets of polygons by using recursion. A monohedral tiling is a tessellation in which all tiles are congruent. Spiral monohedral tilings include the Voderberg tiling discovered by Hans Voderberg in 1936, whose unit tile is a nonconvex enneagon; and the Hirschhorn tiling discovered by Michael Hirschhorn in the 1970s, whose unit tile is an irregular pentagon.

[edit] Self-dual tessellations

Tilings and honeycombs can also be self-dual. All n-dimensional hypercubic honeycombs with Schlafli symbols {4,3n2,4}, are self-dual.

[edit] Tessellations and computer models

A tessellation of a disk used to solve a finite element problem.

These rectangular bricks are connected in a tessellation which, considered as an edge-to-edge tiling, is topologically identical to a hexagonal tiling; each hexagon is flattened into a rectangle whose long edges are divided in two by the neighboring bricks.

This basketweave tiling is topologically identical to the Cairo pentagonal tiling, with one side of each rectangle counted as two edges, divided by a vertex on the two neighboring rectangles. In the subject of computer graphics, tessellation techniques are often used to manage datasets of polygons and divide them into suitable structures for rendering. Normally, at least for realtime rendering, the data is tessellated into triangles, which is sometimes referred to as triangulation. Tessellation is a staple feature of DirectX 11 and OpenGL.[3][4] In computer-aided design the constructed design is represented by a boundary representation topological model, where analytical 3D surfaces and curves, limited to faces and edges constitute a continuous boundary of a 3D body. Arbitrary 3D bodies are often too complicated to analyze directly. So they are approximated (tessellated) with a mesh of small, easy-to-analyze pieces of 3D volume usually either irregular tetrahedrons, or irregular hexahedrons. The mesh is used for finite element analysis. Mesh of a surface is usually generated per individual faces and edges (approximated to polylines) so that original limit vertices are included into mesh. To ensure approximation of the original surface suits needs of the further processing 3 basic parameters are usually defined for the surface mesh generator:

Maximum allowed distance between planar approximation polygon and the surface (aka "sag"). This parameter ensures that mesh is similar enough to the original analytical surface (or the polyline is similar to the original curve). Maximum allowed size of the approximation polygon (for triangulations it can be maximum allowed length of triangle sides). This parameter ensures enough detail for further analysis. Maximum allowed angle between two adjacent approximation polygons (on the same face). This parameter ensures that even very small humps or hollows that can have significant effect to analysis will not disappear in mesh.

Algorithm generating mesh is driven by the parameters. Some computer analyses require adaptive mesh, which is made finer (using stronger parameters) in regions where the analysis needs more detail. Some geodesic domes are designed by tessellating the sphere with triangles that are as close to equilateral triangles as possible.

[edit] Tessellations in nature

Basaltic lava flows often display columnar jointing as a result of contraction forces causing cracks as the lava cools. The extensive crack networks that develop often produce hexagonal columns of lava. One example of such an array of columns is the Giant's Causeway in Northern Ireland. The Tessellated pavement in Tasmania is a rare sedimentary rock formation where the rock has fractured into rectangular blocks.

[edit] Number of sides of a polygon versus number of sides at a vertex

For an infinite tiling, let a be the average number of sides of a polygon, and b the average number of sides meeting at a vertex. Then (a 2)(b 2) = 4. For example, we have the combinations (3, 6), (313 , 5), (334 , 427 ), (4, 4), (6, 3), for the tilings in the article Tilings of regular polygons. A continuation of a side in a straight line beyond a vertex is counted as a separate side. For example, the bricks in the picture are considered hexagons, and we have combination (6, 3). Similarly, for the basketweave tiling often found on bathroom floors, we have (5, 313 ). For a tiling which repeats itself, one can take the averages over the repeating part. In the general case the averages are taken as the limits for a region expanding to the whole plane. In cases like an infinite row of tiles, or tiles getting smaller and smaller outwardly, the outside is not negligible and should also be counted as a tile while taking the limit. In extreme cases the limits may not exist, or depend on how the region is expanded to infinity. For finite tessellations and polyhedra we have

where F is the number of faces and V the number of vertices, and is the Euler characteristic (for the plane and for a polyhedron without holes: 2), and, again, in the plane the outside counts as a face. The formula follows observing that the number of sides of a face, summed over all faces, gives twice the total number of sides in the entire tessellation, which can be expressed in terms of the number of faces and the number of vertices. Similarly the number of sides at a vertex, summed over all vertices, also gives twice the total number of sides. From the two results the formula readily follows. In most cases the number of sides of a face is the same as the number of vertices of a face, and the number of sides meeting at a vertex is the same as the number of faces meeting at a vertex. However, in a case like two square faces touching at a corner, the number of sides of the outer face is 8, so if the number of vertices is counted the common corner has to be counted twice. Similarly the number of sides meeting at that corner is 4,

so if the number of faces at that corner is counted the face meeting the corner twice has to be counted twice. A tile with a hole, filled with one or more other tiles, is not permissible, because the network of all sides inside and outside is disconnected. However it is allowed with a cut so that the tile with the hole touches itself. For counting the number of sides of this tile, the cut should be counted twice. For the Platonic solids we get round numbers, because we take the average over equal numbers: for (a 2)(b 2) we get 1, 2, and 3. From the formula for a finite polyhedron we see that in the case that while expanding to an infinite polyhedron the number of holes (each contributing 2 to the Euler characteristic) grows proportionally with the number of faces and the number of vertices, the limit of (a 2)(b 2) is larger than 4. For example, consider one layer of cubes, extending in two directions, with one of every 2 2 cubes removed. This has combination (4, 5), with (a 2)(b 2) = 6 = 4(1 + 2 / 10)(1 + 2 / 8), corresponding to having 10 faces and 8 vertices per hole. Note that the result does not depend on the edges being line segments and the faces being parts of planes: mathematical rigor to deal with pathological cases aside, they can also be curves and curved surfaces.

[edit] Tessellations of other spaces

A torus can be tiled by a An example repeating matrix of isogonal M.C.Escher, Circle tessellation of the Limit III (1959) quadrilaterals. surface of a sphere by a truncated icosidodecahedron. As well as tessellating the 2-dimensional Euclidean plane, it is also possible to tessellate other n-dimensional spaces by filling them with n-dimensional polytopes. Tessellations of other spaces are often referred to as honeycombs. Examples of tessellations of other spaces include:

Tessellations of n-dimensional Euclidean space. For example, 3-dimensional Euclidean space can be filled with cubes to create the cubic honeycomb.

Tessellations of n-dimensional elliptic space, either the n-sphere (spherical tiling, spherical polyhedron) or n-dimensional real projective space (elliptic tiling, projective polyhedron). For example, projecting the edges of a regular dodecahedron onto its circumsphere creates a tessellation of the 2-dimensional sphere with regular spherical pentagons, while taking the quotient by the antipodal map yields the hemi-dodecahedron, a tiling of the projective plane.

Tessellations of n-dimensional hyperbolic space. For example, M. C. Escher's Circle Limit III depicts a tessellation of the hyperbolic plane (using the Poincar disk model) with congruent fish-like shapes. The hyperbolic plane admits a tessellation with regular p-gons meeting in q's whenever ; Circle Limit III may be understood as a tiling of octagons meeting in threes, with all sides replaced with jagged lines and each octagon then cut into four fish.

See (Magnus 1974) for further non-Euclidean examples. There are also abstract polyhedra which do not correspond to a tessellation of a manifold because they are not locally spherical (locally Euclidean, like a manifold), such as the 11cell and the 57-cell. These can be seen as tilings of more general spaces.

[edit] See also

Coxeter groups algebraic groups that can be used to find tessellations Girih tiles Jigsaw puzzle List of regular polytopes List of uniform tilings Mathematics and fiber arts Nikolas Schiller artist using tessellations of aerial photographs Pinwheel tiling Polyiamond and Polyomino figures consisting of regular triangles and squares respectively, often appearing in tiling puzzles Quilting Tile Tiling puzzle Tilings of regular polygons Trianglepoint needlepoint with polyiamonds (equilateral triangles) Triangulation (geometry) Uniform tessellation Uniform tiling Uniform tilings in hyperbolic plane Voronoi tessellation Wallpaper group seventeen types of two-dimensional repetitive patterns Wang tiles

[edit] Notes

1. ^ tessellate, Merriam-Webster Online 2. ^ Armstrong, M.A. (1988). Groups and Symmetry. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3540966753. 3. ^ http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ff476340%28v=VS.85%29.aspx 4. ^ http://www.opengl.org/registry/doc/glspec40.core.20100311.pdf

[edit] References

Grunbaum, Branko and G. C. Shephard. Tilings and Patterns. New York: W. H. Freeman & Co., 1987. ISBN 0-7167-1193-1. Coxeter, H.S.M.. Regular Polytopes, Section IV : Tessellations and Honeycombs. Dover, 1973. ISBN 0-486-61480-8. Magnus, Wilhelm (1974), Noneuclidean tesselations and their groups, Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12465450-1

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Tessellation Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tessellation" View page ratings

Rate this page

What's this? Trustworthy Objective Complete Well-written

I am highly knowledgeable about this topic (optional) Submit ratings Saved successfully Your ratings have not been submitted yet Categories: Symmetry | Mosaic | Tiling

Personal tools

Log in / create account

Namespaces

Article Discussion

Variants

Views

Read Edit View history

Actions Search

Special:Search

Navigation

Main page Contents Featured content Current events Random article Donate to Wikipedia

Interaction

Help About Wikipedia Community portal Recent changes Contact Wikipedia

Toolbox

What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages Permanent link Cite this page Rate this page

Print/export

Create a book Download as PDF Printable version

Languages

Catal Dansk

Deutsch Espaol Franais Italiano Nederlands ors (bo m l) Piemontis Polski Portugus Slovenina / Srps i Svenska Trke

This page was last modified on 5 September 2011 at 05:52. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. See Terms of use for details. Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization. Contact us

Privacy policy About Wikipedia Disclaimers Mobile view

What are tessellations Basically, a tessellation is a way

to tile a floor (that goes on forever) with shapes so that there is no overlapping and no gaps. Remember the last puzzle you put together? Well, that was a tessellation! The shapes were just really weird.

Example:

We usually add a few more rules to make things interesting!

REGULAR TESSELLATIONS: RULE #1: The tessellation

must tile a floor (that goes on forever) with no overlapping or gaps. RULE #2: The tiles must be regular polygons - and all the same. RULE #3: Each vertex must look the same.

What's a vertex?

where all the "corners" meet!

What can we tessellate using these rules?

Triangles? Yep!

Notice what happens at each vertex!

The interior angle of each equilateral triangle is 60 degrees.....

60 + 60 + 60 + 60 + 60 + 60 = 360 degrees Squares? Yep!

What happens at each vertex?

90 + 90 + 90 + 90 = 360 degrees again!

So, we need to use regular polygons that add up to 360 degrees.

Will pentagons work?

The interior angle of a pentagon is 108 degrees. . .

108 + 108 + 108 = 324 degrees . . . Nope!

Hexagons? 120 + 120 + 120 = 360 degrees Yep!

Heptagons? No way!! Now we are getting overlaps!

Octagons? Nope!

They'll overlap too. In fact, all polygons with more than six sides will overlap! So, the only regular polygons that tessellate are triangles, squares and hexagons!

SEMI-REGULAR TESSELLATIONS:

These tessellations are made by using two or more different regular polygons. The rules are still the same. Every vertex must have the exact same configuration.

Examples:

3, 3, 3, 3, 6 3, 6, 3, 6

These tessellations are both made up of hexagons and triangles, but their vertex configuration is different. That's why we've named them! To name a tessellation, simply work your way around one vertex counting the number of sides of the polygons that form that vertex. The trick is to go around the vertex in order so that the smallest numbers possible appear first. That's why we wouldn't call our 3, 3, 3, 3, 6 tessellation a 3, 3, 6, 3, 3! Here's another tessellation made up of hexagons and triangles. Can you see why this isn't an official semi-regular tessellation?

It breaks the vertex rule! Do you see where?

Here are some tessellations using squares and triangles:

3, 3, 3, 4, 4

3, 3, 4, 3, 4

Can you see why this one won't be a semi-regular tessellation?

MORE SEMI-REGULAR TESSELLATIONS

What others semi-regular tessellations can you think of?

Related searches: easy tessellation patterns simple tessellation patterns animal tessellation patterns tessellation patterns for kids

Search Results

1.

o o o o o o o o o o

Page 2

o

Page 3

o

Page 4

Page 5

o

Page 6

Page 7

Page 8

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11

Page 12

Page 13

Page 14

Page 15

o

Page 16

Page 17

o

Page 18

o

Page 19

o

Page 20

o

Page 21

tessellation patterns

en

1034

508

isch

Google Images Home Report Offensive Images Switch to basic versionHelpGive us feedback

Google HomeAdvertising ProgramsBusiness SolutionsPrivacyAbout Google

Вам также может понравиться

- TessellationДокумент22 страницыTessellationDesai RameshОценок пока нет

- Tessellation PWPointДокумент9 страницTessellation PWPointDesai RameshОценок пока нет

- Tessellation PWPointДокумент9 страницTessellation PWPointDesai RameshОценок пока нет

- Energy Scenario: Syllabus Energy Scenario: Commercial and Non-Commercial Energy, Primary Energy ResourcesДокумент36 страницEnergy Scenario: Syllabus Energy Scenario: Commercial and Non-Commercial Energy, Primary Energy ResourcesCelestino Montiel MaldonadoОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5783)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Temperature Rise HV MotorДокумент11 страницTemperature Rise HV Motorashwani2101Оценок пока нет

- Effectiveness of Laundry Detergents and Bars in Removing Common StainsДокумент9 страницEffectiveness of Laundry Detergents and Bars in Removing Common StainsCloudy ClaudОценок пока нет

- Sale of GoodsДокумент41 страницаSale of GoodsKellyОценок пока нет

- BrianmayДокумент4 страницыBrianmayapi-284933758Оценок пока нет

- Official Website of the Department of Homeland Security STEM OPT ExtensionДокумент1 страницаOfficial Website of the Department of Homeland Security STEM OPT ExtensionTanishq SankaОценок пока нет

- Who Are The Prosperity Gospel Adherents by Bradley A KochДокумент46 страницWho Are The Prosperity Gospel Adherents by Bradley A KochSimon DevramОценок пока нет

- Jason Payne-James, Ian Wall, Peter Dean-Medicolegal Essentials in Healthcare (2004)Документ284 страницыJason Payne-James, Ian Wall, Peter Dean-Medicolegal Essentials in Healthcare (2004)Abdalmonem Albaz100% (1)

- Mental Health Admission & Discharge Dip NursingДокумент7 страницMental Health Admission & Discharge Dip NursingMuranatu CynthiaОценок пока нет

- How To Use Google FormsДокумент126 страницHow To Use Google FormsBenedict Bagube100% (1)

- ScriptsДокумент6 страницScriptsDx CatОценок пока нет

- A Review Article On Integrator Circuits Using Various Active DevicesДокумент7 страницA Review Article On Integrator Circuits Using Various Active DevicesRaja ChandruОценок пока нет

- How To Download Gateways To Democracy An Introduction To American Government Book Only 3Rd Edition Ebook PDF Ebook PDF Docx Kindle Full ChapterДокумент36 страницHow To Download Gateways To Democracy An Introduction To American Government Book Only 3Rd Edition Ebook PDF Ebook PDF Docx Kindle Full Chapterandrew.taylor131100% (22)

- Unitrain I Overview enДокумент1 страницаUnitrain I Overview enDragoi MihaiОценок пока нет

- TDS Tetrapur 100 (12-05-2014) enДокумент2 страницыTDS Tetrapur 100 (12-05-2014) enCosmin MușatОценок пока нет

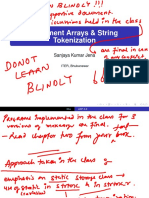

- USP 11 ArgumentArraysДокумент52 страницыUSP 11 ArgumentArraysKanha NayakОценок пока нет

- Module 3 - Risk Based Inspection (RBI) Based On API and ASMEДокумент4 страницыModule 3 - Risk Based Inspection (RBI) Based On API and ASMEAgustin A.Оценок пока нет

- General Physics 1: Activity Title: What Forces You? Activity No.: 1.3 Learning Competency: Draw Free-Body DiagramsДокумент5 страницGeneral Physics 1: Activity Title: What Forces You? Activity No.: 1.3 Learning Competency: Draw Free-Body DiagramsLeonardo PigaОценок пока нет

- Review 6em 2022Документ16 страницReview 6em 2022ChaoukiОценок пока нет

- Relay Models Per Types Mdp38 EnuДокумент618 страницRelay Models Per Types Mdp38 Enuazer NadingaОценок пока нет

- Healthy Kitchen Shortcuts: Printable PackДокумент12 страницHealthy Kitchen Shortcuts: Printable PackAndre3893Оценок пока нет

- Article Summary Assignment 2021Документ2 страницыArticle Summary Assignment 2021Mengyan XiongОценок пока нет

- NAME: - CLASS: - Describing Things Size Shape Colour Taste TextureДокумент1 страницаNAME: - CLASS: - Describing Things Size Shape Colour Taste TextureAnny GSОценок пока нет

- Garner Fructis ShampooДокумент3 страницыGarner Fructis Shampooyogesh0794Оценок пока нет

- Exp Mun Feb-15 (Excel)Документ7 510 страницExp Mun Feb-15 (Excel)Vivek DomadiaОценок пока нет

- AmulДокумент4 страницыAmulR BОценок пока нет

- Cognitive Development of High School LearnersДокумент30 страницCognitive Development of High School LearnersJelo BacaniОценок пока нет

- Mitanoor Sultana: Career ObjectiveДокумент2 страницыMitanoor Sultana: Career ObjectiveDebasish DasОценок пока нет

- Kina Finalan CHAPTER 1-5 LIVED EXPERIENCES OF STUDENT-ATHLETESДокумент124 страницыKina Finalan CHAPTER 1-5 LIVED EXPERIENCES OF STUDENT-ATHLETESDazel Dizon GumaОценок пока нет

- Cambridge IGCSE: 0500/12 First Language EnglishДокумент16 страницCambridge IGCSE: 0500/12 First Language EnglishJonathan ChuОценок пока нет