Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Construction Law Bulletin March 2004

Загружено:

dirk hennИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Construction Law Bulletin March 2004

Загружено:

dirk hennАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Cox Yeats

ATTORNEYS

March 2004

CONSTRUCTION LAW BULLETIN

paving laid on the fill. No provision was made for drainage of the newly filled area. VOETSTOOTS CLAUSES Voetstoots clauses are invariably included in sale contracts relating to immovable property. Their purpose is to insulate a seller against claims by the buyer relating to latent defects in the property. In terms of our common law, sellers impliedly warrant to buyers that articles sold are free of latent defects. Ordinarily the only limitation on the protection afforded by such clauses is in those circumstances where the seller knows about the defect at the time of the sale and purposefully conceals the defect from the buyer. The Cape High Court 1 at the end of last year added a further limitation to the reach of voetstoots clauses. In carrying out this work, Mr Barnes did not see fit to enlist the advice or the services of a structural engineer or any other suitably qualified person. In May 1997 Mr Barnes sold the property to the P&L Trust. The sale agreement contained the following provision: 9. Warranties and undertakings 9.1 The property is hereby sold voetstoots subject to all existing servitudes and title deed conditions. Approximately a year later, in 1998, the retaining wall collapsed causing extensive damage. The P&L Trust sued Mr Barnes for the costs of repairing the retaining wall and the damage caused by its collapse. BASIS OF CLAIM Had the voetstoots clause not been contained in the sale agreement, the P&L Trust would have been entitled to base a claim on the common law implied warranty against latent defects which is a normal incidence of every sale contract. The Trust initially contended that the voetstoots clause did not apply because Mr Barnes had been aware of the defect and had intentionally concealed it. The Trust however did not persist with this line of attack. The Trusts principal attack was advanced not in the law of contract but in the law of delict. In terms of the law of delict you can be held liable for damages suffered by another person if the requis ite ingredients giving rise to delictual liability are present. The ingredients for delictual liability are:

THE FACTS In 1996 Mr Henry Barnes bought a vacant property on a steep slope on the Tygerberg overlooking the Cape Peninsula. He designed and built a dwelling on the property. On the southern boundary between the property and a lower adjoining property there was a pre-existing retaining wall approximately 2 metres high which had been erected by the neighbour. Mr Barnes, with the permission of the neighbour, increased the height of the retaining wall by building on top of it. In doing so, Mr Barnes increased the retaining part of the wall and built a free standing wall on top of the retaining section of approximately 1,2 metres. Fill was placed against the new retaining section and

1

Paul Leatham Humphrys NO v Henry John Barnes High Court of South Africa, Cape of Go od Hope Provincial Division, Case No A1236/02.

Page 2

A wrongful act an act is wrongful if you owe a person a duty of care and you transgress that duty. Fault fault is present if you have acted negligently or intentionally. You are negligent if you foresee the possibility of harm and you do not take reasonable and practicable steps to guard against the harm arising. Patrimonial loss caused by the negligent or intentional action.

The court explained that a voetstoots clause only limits the contractual liability of a seller for latent defects in the property sold. It does not exclude liability for anything else such as for example negligence or misrepresentation.3 It would have been permissible for Mr Barnes to have included a clause excluding liability for delictual claims in the sale agreement. In the absence of such a provision, Mr Barnes was held liable for the Trusts damages claim. Sellers beware.

The Trust argu ed that Mr Barnes had owed it and for that matter successive purchasers of the property a duty of care and that he had breached that duty of care by negligently constructing a retaining wall without the necessary structural integrity and not in accordance with the National Building Regulations. Importantly, he had failed to secure the services of a competent structural engineer in building the wall.

PRESCRIPTION OF ARBITRATORS AWARD An arbitrators award prescribes after the elapse of three years unless it is made an order of court in which case a 30 year prescriptive period applies.4

COURTS FINDING Expert evidence at the trial demonstrated that the increased fill, the free standing wall on top of the retaining wall and the lack of drainage all contributed to an excessive increase in the bending moment of the wall which caused its collapse. The court in fact found that neither the original retaining wall nor the extension constructed by Mr Barnes had been built with the necessary structural integrity and in accordance with the National Building Regulations. In the circumstances the court found that both the neighbour and Mr Barnes had breached a duty of care owed to successive owners of the Barnes property to ensure the integrity of the structure and their negligence in this regard had caused the collapse of the wall. The Trust had in the action only made a claim against Mr Barnes and not the neighbour. Whilst this may at first blush appear to be unfair, it is expressly allowed in our law of delict where the principle has been expressed as follows 2 : a plaintiff can hold a defendant liable whose negligence has materially contributed to a totality of loss resulting partly also from the acts of other persons or from the forces of nature, even though no precise allocation of portions of the loss to the contributing factors can be made. In relation to whether the voetstoots clause provided Mr Barnes with a shield against the Trusts delictual claim, the court found that it did not.

3 4 2

ALASTAIR HAY COX YEATS 12th Floor, Victoria Maine 71 Victoria Embankment P O Box 3032 DURBAN Tel: (031) 304 2851 Fax: (031) 301 3540 ahay@coxyeats.co.za

Kakamas Bestuursraad v Louw 1960(2) SA 202A at 222A-C.

Cockroft v Baxter 1955(4) SA 93C at 98B-C. Prima Vera Construction v Government North West Province 2003(3) SA 579B.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

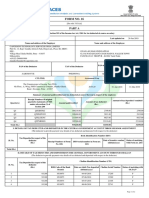

- Form16 2018 2019Документ10 страницForm16 2018 2019LogeshwaranОценок пока нет

- RYA-MCA Coastal Skipper-Yachtmaster Offshore Shorebased 2008 AnswersДокумент28 страницRYA-MCA Coastal Skipper-Yachtmaster Offshore Shorebased 2008 AnswersSerban Sebe100% (4)

- Lockbox Br100 v1.22Документ36 страницLockbox Br100 v1.22Manoj BhogaleОценок пока нет

- Food and Beverage Department Job DescriptionДокумент21 страницаFood and Beverage Department Job DescriptionShergie Rivera71% (7)

- 500 Logo Design Inspirations Download #1 (E-Book)Документ52 страницы500 Logo Design Inspirations Download #1 (E-Book)Detak Studio DesainОценок пока нет

- Hotel ManagementДокумент34 страницыHotel ManagementGurlagan Sher GillОценок пока нет

- Digital LiteracyДокумент19 страницDigital Literacynagasms100% (1)

- Sourcing Decisions in A Supply Chain: Powerpoint Presentation To Accompany Powerpoint Presentation To AccompanyДокумент58 страницSourcing Decisions in A Supply Chain: Powerpoint Presentation To Accompany Powerpoint Presentation To AccompanyAlaa Al HarbiОценок пока нет

- Ytrig Tuchchh TVДокумент10 страницYtrig Tuchchh TVYogesh ChhaprooОценок пока нет

- Manual 40ku6092Документ228 страницManual 40ku6092Marius Stefan BerindeОценок пока нет

- Social Media Marketing Advice To Get You StartedmhogmДокумент2 страницыSocial Media Marketing Advice To Get You StartedmhogmSanchezCowan8Оценок пока нет

- LMU-2100™ Gprs/Cdmahspa Series: Insurance Tracking Unit With Leading TechnologiesДокумент2 страницыLMU-2100™ Gprs/Cdmahspa Series: Insurance Tracking Unit With Leading TechnologiesRobert MateoОценок пока нет

- Supergrowth PDFДокумент9 страницSupergrowth PDFXavier Alexen AseronОценок пока нет

- Innovations in Land AdministrationДокумент66 страницInnovations in Land AdministrationSanjawe KbОценок пока нет

- Tinplate CompanyДокумент32 страницыTinplate CompanysnbtccaОценок пока нет

- Abu Hamza Al Masri Wolf Notice of Compliance With SAMs AffirmationДокумент27 страницAbu Hamza Al Masri Wolf Notice of Compliance With SAMs AffirmationPaulWolfОценок пока нет

- Basics: Define The Task of Having Braking System in A VehicleДокумент27 страницBasics: Define The Task of Having Braking System in A VehiclearupОценок пока нет

- Chapter 5Документ3 страницыChapter 5Showki WaniОценок пока нет

- Enerparc - India - Company Profile - September 23Документ15 страницEnerparc - India - Company Profile - September 23AlokОценок пока нет

- Microwave Drying of Gelatin Membranes and Dried Product Properties CharacterizationДокумент28 страницMicrowave Drying of Gelatin Membranes and Dried Product Properties CharacterizationDominico Delven YapinskiОценок пока нет

- Ingles Avanzado 1 Trabajo FinalДокумент4 страницыIngles Avanzado 1 Trabajo FinalFrancis GarciaОценок пока нет

- Everlube 620 CTDSДокумент2 страницыEverlube 620 CTDSchristianОценок пока нет

- MSDS - Tuff-Krete HD - Part DДокумент6 страницMSDS - Tuff-Krete HD - Part DAl GuinitaranОценок пока нет

- Cancellation of Deed of Conditional SalДокумент5 страницCancellation of Deed of Conditional SalJohn RositoОценок пока нет

- BASUG School Fees For Indigene1Документ3 страницыBASUG School Fees For Indigene1Ibrahim Aliyu GumelОценок пока нет

- BMA Recital Hall Booking FormДокумент2 страницыBMA Recital Hall Booking FormPaul Michael BakerОценок пока нет

- Dissertation On Indian Constitutional LawДокумент6 страницDissertation On Indian Constitutional LawCustomPaperWritingAnnArbor100% (1)

- Micron Interview Questions Summary # Question 1 Parsing The HTML WebpagesДокумент2 страницыMicron Interview Questions Summary # Question 1 Parsing The HTML WebpagesKartik SharmaОценок пока нет

- Sophia Program For Sustainable FuturesДокумент128 страницSophia Program For Sustainable FuturesfraspaОценок пока нет

- SAS SamplingДокумент24 страницыSAS SamplingVaibhav NataОценок пока нет