Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

KM Barriers

Загружено:

polz2007Исходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

KM Barriers

Загружено:

polz2007Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

ISSN 1750-9653, England, UK International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management Vol. 3 (2008) No. 2, pp.

141-150

Knowledge management barriers: An interpretive structural modeling approach

M. D. Singh , R. Kant Department of Mechanical Engineering, Motilal Nehru National Institute of Technology, Allahabad, India (Received December 12 2007, Accepted January 21 2008) Abstract. In the fast changing global business, knowledge management (KM) has emerged as an integral part of business strategy. Many business organizations have implemented KM and many are in the process of its implementation. KM implementation is adversely affected by few factors which are known as KM barriers. The objective of this paper is to develop the relationships among the identied KM barriers. Further, this paper is also helpful to understand mutual inuences of barriers and to identify those barriers which support other barriers (driving barrier) and also those barriers which are most inuenced by other barriers (dependent barriers). The interpretive structural modeling (ISM) methodology is used to evolve mutual relationships among these barriers. KM barriers have been classied, based on their driving power and dependence power. The objective behind this classication is to analyze the driving power and dependence power of these barriers. Keywords: barriers, dependence power, driving power, interpretive structural modeling, knowledge management

Introduction

KM implementation is one of the major attractions among the researchers and practitioners. The business organizations are more concerned about building the knowledge assets for their competiveness. KM effort is no longer merely an option but rather a core necessity for organizations any where in the world, if they have to compete successfully[33, 36] . KM is the deliberate and systematic coordination of an organizations people, technology, processes and organizational structure in order to add value through reuse and innovation. This coordination is achieved by creating, sharing and applying knowledge as well as through feeding the valuable lessons learnt and incorporating the best practices into corporate memory in order to foster continued organizational learning[13] . KM also facilitates ow of knowledge and sharing to improve the efciency of individuals and hence the organizations. There are many factors that adversely affect the success of KM implementation in the organizations, known as KM barriers. These may be internal and external type barriers. Internal barriers originate from organizational cultures, organizational structures, etc. The second group of barriers is outside the immediate control of the organization[41] . The aim of this paper is to develop the relationships among the identied barriers using interpretive structural modeling (ISM) and classify theses barriers depending upon their driving and dependence power. ISM is a well established methodology for identifying relationships among specic items which dene a problem or an issue[31, 37] . The opinions from group of experts are used in developing the relationship matrix, which was later used in the development of the ISM model. These barriers are derived theoretically from various literature sources, and experts discussion (See Tab. 1). Some barriers are extracted from the work of those who have explored KM in general or have addressed a particular barrier in detail. Although different researchers have used different terminologies to indicate these barriers, they can be represented by generic

Corresponding author. Tel: +91-532-2271513; E-mail address: mds nit@yahoo.com Published by World Academic Press, World Academic Union

142

M. Singh & R. Kant: Knowledge management barriers

themes. In addition, they have also been mentioned in the literature with a mixed extent of emphasis and coverage.

Table 1. Knowledge management barriers Barriers Number 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Barrier Description Lack of top management commitment Lack of technological infrastructure Lack of methodology Lack of organizational structure Lack of organizational culture Lack of motivation and reward Staff retirement Lack of ownership of problem Staff defection References [1], [7], [12], [20], [40], [41] [1], [4], [8], [11], [12], [40] [1], [11] [11], [30] [1], [4], [9], [10], [12], [30] [1], [12], [30], [41] [1] [1], [10], [30] [1], [30]

KM Barriers: Literature Review

Barriers, which hinder organizations to implement KM, have been identied from various authors who have researched and written directly on this issue. One of the earliest sets of barriers for implementing KM was reported by a study of Fraunhofer Stuttgart. According to this study, scarcity of time and lack of awareness about KM were the most important barriers to implement KM [8]. Aligned with this type of approach, another study to explore the practices has identied three major barriers namely scarcity of time, lack of awareness and lack of top management support, to implement KM[20] . Based on lessons captured from leading organizations, two of the KPMG (Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler) studies have proposed four (lack of time, lack of understanding of KM and its benets, lack of funding and lack of senior management support) and ve (lack of time, the sharing of ones own knowledge, an unclear strategy, weaknesses of information communication technology support, and unclear information demand) key barriers respectively to KM initiatives[1, 2] . The Delphi study has proposed three barriers, among which culture was the top most barrier and immature technology and lack of need of KM were the minor barriers [17]. Another survey has identied culture, leadership, lack of understanding, efforts vs. reward, technology and knowledge complexity as barriers to KM implementation [26]. A survey of Indian engineering industries has proposed twenty barriers, amongst them, lack of understanding of KM and lack of top management commitment have been identied as top most barriers. According to this survey, there is a need for KM strategy which must be supported by top management and requires a good KM infrastructure, staff retention, and incentives to encourage knowledge sharing[36] . Reference [32] shows culture as a main barrier and lack of time, and lack of ownership of problem as two other barriers. Reference [30] classies barriers into three categories namely organizational, individual and technological barriers. Organizational barriers are lack of leadership, organizational structure, processes etc. Individual barriers are lack of time to share knowledge, job security, benet of KM, low awareness and realization of the value etc. Technological barriers are lack of integration of information technology system, unrealistic expectation of employees, lack of training etc. Based on the literature review, the authors have identied nine barriers to KM initiatives in the organization (See Tab. 1).These barriers are explained in the following sub-sections. 2.1 Lack of top management commitment

Top management is responsible for each and every activity at all the levels of the organizations. It is instrumental in development of organizational structure, technological infrastructure and various decisions making processes which are essential for effective creation, sharing and use of knowledge. Effective knowledge creation and sharing require long term commitment and support from top management in recruitment and

MSEM email for contribution: submit@msem.org.uk

International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management, Vol. 3 (2008) No. 2, pp. 141-150

143

retention of right people[7] . Lack of top management is the most critical barrier for a successful KM implementation, particularly in knowledge creation and sharing[11] . It is also responsible for identifying organizational strength and weaknesses as well as analyzing the opportunities and threads in the external environment[16] . The top management has to conceptualize a vision about what type of knowledge should be developed and used into a management system for implementation[28] . 2.2 Lack of technological infrastructure

As most of the issues of KM are culture based, the role of technology cant be overlooked. Lack of technological infrastructure (TI) is one of the barriers in implementation of KM. TI provides a stronger platform to KM and enhances its impact in an organization, by helping and leveraging its knowledge systematically and actively[34] . The wide varieties of technology such as business intelligence, knowledge base, collaboration, portals, customer management systems, data mining, workow, etc., support KM activities and the selection of appropriate technology improves the performance of businesses[35] .TI enables collecting, dening, storing, indexing and linking data, and digital objects in order to support management decisions[9] . It is able to overcome the barriers of time and space. It also serves as a repository in which knowledge can be reliably stored and efciently retrieved[12] . 2.3 Lack of methodology

KM is a group of clearly dened processes or methods used to search important knowledge among different KM operations[38] . Despite top management commitment, organizational structure and technological support, KM may fail due to lack of methodology. Successful KM implementation requires a set of methodology[36] . Methodology denes each and every activity which is going to be held during the KM implementation. It is necessary for enhancing KM implementation. Many authors[13, 22, 27] have suggested the step-by-step methodology for KM implementation. But even though, when it comes to real implementation, they fail. Organizations have to understand those guidelines and transfer them according to their context. 2.4 Lack of organizational structure

Business organizations should adopt an organizational structure (OS) which matches and supports its strategy. OS includes division of labor, departmentalization and distribution of power which is necessary to support the information and decision process of the organizations. It is dened as the specication of jobs to be done within an organization and the ways in which those jobs relate to one another[15] . There are two types of organizational structure; one is bureaucracy and the other is task force[28] . Bureaucratic structure hinders the ow of knowledge, hence it should be discouraged. Task force structure is exible and adoptable which brings a team or group together to deal with problems[4] . OS needs to support the knowledge transfer and must contribute towards creation and reuse of knowledge for the successful implementation of KM in the organizations. It must be capable enough to administer the knowledge related activities. Creating an organizational structure to manage knowledge is by no means enough for the success of KM, but it is an important ingredient of success[14] . Lack of organizational structure can discourage the KM activities which certainly hinder the prospect of KM in the organizations. 2.5 Lack of organizational culture

Organizational culture denes the core beliefs, value norms and social customs that govern the way individuals act and behave in an organization. It is the sum of shared philosophies, assumptions, values, expectations, attitudes, and norms that bind the organizations together[21] . Lack of organizational culture is a key barrier for successful implementation of knowledge management in an organization. Organizational culture is the largest barrier in creation of a successful knowledge-based organization[10]. Culture considers the multiple aspects mainly collaboration and trust. Trust is one of the aspects of the knowledge friendly cultures that fosters the relationship between individuals and groups, thereby, facilitating a more proactive and open knowledge sharing[3] . Absence or minimal level of collaboration hinders the transfer of knowledge between individuals as well as of the groups.

MSEM email for subscription: info@msem.org.uk

144

M. Singh & R. Kant: Knowledge management barriers

2.6

Lack of motivation and rewards

Organizational goals cant be achieved unless organizations integrate the concept of motivation and rewards to its employees. Motivation can be provided through recognition, visibility, and inclusion of knowledge performance in appraisal systems and incentives[18] . The motivation could be either intrinsic or extrinsic. Rewarding and recognizing an employee with tangible form for their knowledge sharing efforts is extrinsic motivation while intrinsic motivation is intangible nature[5] . Employees share their knowledge easily when motivated. It is critical for sharing of both types of knowledge tacit as well as explicit knowledge. One of the examples of motivation and reward system practices by Bharti Cellular Limited is of knowledge-dollar (K$) scheme, under which employees earn points or K$s every time when they share new knowledge in an organization knowledge base or every time they replicate or apply knowledge shared by others[19] . Lack of motivation and reward system is also a barrier because it discourages people to create, share, and use knowledge. Without the establishment of organizational reward and recognition systems, it is very difcult to align the KM and business needs of the organizations[39] . 2.7 Staff retirement

Staff retirement is the major barrier in the KM implementation. Many organizations are facing lot of problems due to expertise retirement[36] . If any employee retires from his/her job, it is very difcult to get a substitute of that level. His/her experience and expertise will be lost by the organizations. Organizations are less vigilant about protecting their human intellectual capital. Organizations need to focus on knowledge retention and its transfer into their business process management[13] . According to Accenture, one out of four organizations makes no effort whatsoever to capture the workplace knowledge of retirees, and a further 16% of organizations expect retirees to have an informal chat with colleagues before leaving. Thats more than 40% of the organizations have no formal processes for retaining expertise[29] . 2.8 Lack of ownership of problem

Lack of ownership of problem is another issue which proves to be a barrier for KM implementation[2, 23] . Due to the lack of ownership of problem, no employee is ready to take up the jobs unless it has been properly assigned. This situation is basically due to absence of culture in the organizations. Employees are not ready to take the responsibility of unassigned jobs. This situation makes difcult to nurture the KM implementation in the organizations. 2.9 Staff defection

Increasing Staff defection rates are mainly due to the demand for sound trained and skilled personnel. Lack of motivation and reward also contributes in staff turnover. It has much inuence on KM implementation[36] . The loss of knowledge through staff defections is a critical driver of KM[25] . KM program fails due to staff defection and brings instability to the organization. Staff defection affects the organizations in many ways. One of which is in the knowledge it uses in its day-to-day business. Organizations have to formulate successful strategies for minimizing the staff turnover.

ISM Methodology and Model Development

ISM methodology helps to impose order and direction on the complexity of relationships among elements of a system[31] . It is interpretive as the judgment of the group decides whether and how the variables are related. It is structural as on the basis of relationship, an overall structure is extracted from the complex set of variables. It is a modeling technique as the specic relationships and overall structure are portrayed in a graphical model. The various steps involved in the ISM technique are: (1). Identifying elements which are relevant to the problem or issues-this could be done by survey;

MSEM email for contribution: submit@msem.org.uk

International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management, Vol. 3 (2008) No. 2, pp. 141-150

145

(2). Establishing a contextual relationship between elements with respect to which pairs of elements would be examined; (3). Developing a structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM) of elements which indicates pair-wise relationship between elements of the system; (4). Developing a reachability matrix from the SSIM, and checking the matrix for transitivity - transitivity of the contextual relation is a basic assumption in ISM which states that if element A is related to B and B is related to C, then A is related to C; (5). Partitioning of the reachability matrix into different levels; (6). Based on the relationships given above in the reachability matrix, drawing a directed graph (digraph), and removing the transitive links; (7). Converting the resultant digraph into an ISM-based model by replacing element nodes with the statements; and (8). Reviewing the model to check for conceptual inconsistency and making the necessary modications. The various steps, which lead to the development of ISM model, are illustrated below. 3.1 Structural self-interaction matrix (SSIM)

Group of experts, from industries and the academics were consulted in identifying the nature of contextual relationships among the barriers (see Tab. 1). For analyzing the barriers in developing SSIM, the following four symbols have been used to denote the direction of relationship between barriers (i and j): V - Barrier i will help to achieve barrier j; A - Barrier j will help to achieve barrier i; X - Barriers i and j will help to achieve each other; and O - Barriers i and j are unrelated.

Table 2. Structural self-interaction matrix (ssim) Barrier Number 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Barrier Description Lack of top management commitment Lack of technological infrastructure Lack of methodology Lack of organizational structure Lack of organizational culture Lack of motivation and reward Staff retirement Lack of ownership of problem Staff deection 9 V V V V V V O A X 8 V V V V V V V Barrier Number 7 6 5 4 V V V V V V V A V V V X V V V V V V 3 V A 2 V

3.2

Reachability matrix

The SSIM has been converted into a binary matrix, called the initial reachability matrix (see Tab. 3) by substituting V , A, X and O by 1 and 0 as per given case. The substitution of 1s and 0s are as per the following rules: If the (i, j) entry in the SSIM is V , the (i, j) entry in the reachability matrix becomes 1 and the (j, i) entry becomes 0; If the (i, j) entry in the SSIM is A, the (i, j) entry in the reachability matrix becomes 0 and the (j, i) entry becomes 1; If the (i, j) entry in the SSIM is X, the (i, j) entry in the reachability matrix becomes 1 and the (j, i) entry also becomes 1; and If the (i, j) entry in the SSIM is O, the (i, j) entry in the reachability matrix becomes 0 and the (j, i) entry also becomes 0.

MSEM email for subscription: info@msem.org.uk

146

M. Singh & R. Kant: Knowledge management barriers

Since, there is no transitivity in this case; hence initial reachability matrix (see Tab. 3) will be used for further calculations. The driving power and the dependence of each barrier are shown in Tab. 3. The driving power for each barrier is the total number of barriers (including itself), which it may help achieve. Dependence is the total number of barriers (including itself), which may help achieve it.

Table 3. Initial reachability matrix Barrier Number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Barrier Description Lack of top management commitment Lack of technological infrastructure Lack of methodology Lack of organizational structure Lack of organizational culture Lack of motivation and reward Staff retirement Lack of ownership of problem Staff deection Dependence power 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 2 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 4 3 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 3 Barrier Number 4 5 6 7 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 3 5 6 7 8 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 9 9 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 7 Driving power 9 6 8 8 5 4 2 1 2

3.3

Level partitions

From the nal reachability matrix, the reachability and antecedent set for each barrier is found[37] . The reachability set consists of the element itself and the other elements which it may help achieve, whereas the antecedent set consists of the element itself and the other elements which may help in achieving it. Thereafter, the intersection of these sets is derived for all the barriers. The barriers for which the reachability and the intersection sets are the same occupy the top level in the ISM hierarchy. The top-level element in the hierarchy would not help achieve any other element above its own level. Once the top-level element is identied (see Tab. 4), it is separated out from the other elements. Then, the same process is repeated to nd out the elements in the next level. This process is continued until the level of each element is found (see Tab. 5). These levels help in building the diagraph and the nal model

Table 4. P artition of reachability matrix: rst iteration Barrier Number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Reachability Set 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 6, 7, 8, 9 7, 8 8 8, 9 Antecedent Set 1 1, 2, 3, 4 1, 3, 4 1, 3, 4 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9 Intersection 1 2 3, 4 3, 4 5 6 7 8 9 Level

Classication of barriers

All barriers have been classied, based on their driving power and dependence power, into four categories as autonomous barriers, dependent barriers, linkage barriers, and independent barriers. These classications

MSEM email for contribution: submit@msem.org.uk

International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management, Vol. 3 (2008) No. 2, pp. 141-150

147

Table 5. Levels of km barriers Barrier Number 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Reachability Set 1 2 3, 4 3, 4 5 6 7 8 9 Antecedent Set 1 1, 2, 3, 4 1, 3, 4 1, 3, 4 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9 Intersection 1 2 3, 4 3, 4 5 6 7 8 9 Level VII V VI VI IV III II I II

of barriers are similar to classication used by Mandal and Deshmukh[24] . The driving power and dependence power diagram for barriers is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Cluster of km barriers

It is observed that barrier 2 has a driving power of 6 and a dependence power of 4 (see Tab. 3) and therefore, it is positioned at a place which corresponds to a driving power of 6 and a dependence power of 4 as shown in Fig. 1. The objective behind the classication of barriers is to analyze the driving power and dependence power of the barriers. In this classication of barriers, the rst cluster is of autonomous barriers that have a weak driving power and weak dependence power. The autonomous barriers are relatively disconnected from the system. In the present case, there are no autonomous barriers. The second cluster consists of dependent barriers that have weak driving power and strong dependence power. In the present case, barriers 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 are in the category of dependent barriers. The third cluster consists of linkage barriers that have strong driving and dependence power. Any action on these barriers will have an effect on the other barriers and also a feedback effect on themselves. In this case, there are no linkage barriers. The fourth cluster includes independent barriers that have strong driving power and weak dependence power. In this case, barriers 1, 2, 3, and 4 are in the category of independent barriers.

MSEM email for subscription: info@msem.org.uk

148

M. Singh & R. Kant: Knowledge management barriers

Formation of ISM digraph and model

The structural model is generated from initial reachability matrix (see Tab. 3). If there is a relationship between the barriers i and j, this is presented by an arrow which points from i to j. This graph is called as an initial directed graph, or initial digraph. After removing the transitivities - see step 4 of the ISM methodologythe nal digraph is formed (Fig. 2). This nal digraph is converted into the ISM-based model (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Final digraph depicting the relationship among the km barriers

Discussion

The levels of barriers are important in understanding of successful KM implementation. Lack of top management commitment is the most important barrier due to its high driving power and low dependence among all the identied KM barriers. This can be validated by the previous surveys results [1, 40].This barrier is positioned at the lowest level in the hierarchy of the ISM-based model. The barrier, lack of ownership of problem, is at the highest level in the ISM-based model due to its high dependence power and low driving power. Those barriers which are at the fourth and third levels in the model with highest driving power are known as strategic barriers. These barriers play a key role in knowledge sharing and also in supporting communication, collaboration, and in searching for knowledge and information. These barriers require greater attention from the top management. The driving power and dependence power diagram gives some valuable insights about the relative importance and interdependencies of the barriers. The driving power and dependence diagram (Fig. 1) indicates that there is no autonomous barrier in the process of successful KM. Autonomous barriers are weak drivers and weak dependents. These barriers do not have much inuence on the KM system. The absence of autonomous barriers in this study indicates that all the identied barriers inuence the process of successful knowledge management. Therefore, it is suggested that management should pay serious attention to all KM barriers.

Conclusion and future directions

The levels of barriers are important in the KM implementation process. It can also be observed from Fig. 1 that three barriers, namely lack of top management commitment (barriers 1), lack of methodology (barriers 3), and lack of organizational structure (barriers 4) have high driving power and less dependence power. Therefore, these barriers can be treated as key KM barriers. On the basis of above discussion, we can conclude that all the nine barriers are important (although in varying degrees) for the purpose of successful implementation of KM. In this research only nine KM barriers have been used to develop the ISM model,

MSEM email for contribution: submit@msem.org.uk

International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management, Vol. 3 (2008) No. 2, pp. 141-150

149

Fig. 3. Ism based model

but more KM barriers can be included to develop the relationship among them using the ISM methodology. Further, in this research, the relationship model among the identied KM barriers has not been statistically validated. Structural equation modeling (SEM), also referred to as linear structural relationship approach, has the capability of testing the validity of such hypothetical models. Thus, this approach can be applied in the future research to test the validity of this model. ISM is a tool which can be helpful to develop an initial model whereas SEM has the capability of statistically testing an already developed theoretical mode. Hence, it has been suggested that future research may be targeted to develop the initial model through ISM and then testing it using SEM.

References

[1] Knowledge management research report 1998. in: KPMG Management Consulting (K. Consulting, ed.), 1998. [2] Knowledge management in the context of ebusiness. status quo and perspectives 2001. Berlin, 2001. (in German). [3] A. Alawi, A. Marzooqi, Y. Mohammed. Organizational culture and knowledge sharing: critical success factors. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2007, 11(2): 2242. [4] Z. Ang, P. Massingham. National culture and the standardization versus adaptation of knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2007, 11(2): 521. [5] S. Bhirud, L. Rodrigues, P. Desai. Knowledge sharing practices in km: A case study in indian software subsidiary. Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, 2005, 6. Available at http://www.tlainc.com/jkmp.htm (accessed on July 15, 2007). [6] A. Bollinger, R. Smith. Managing organizational knowledge as a strategic asset. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2001, 5(1): 818. [7] A. Brand. Knowledge management and innovation at. Journal of Knowledge Management, 1998, 2(1): 1722. [8] H. Bullinger, K. Worner, J. Prieto. Knowledge management today: Data, facts, trend, (in german). Stuttgart, 1997. Institut fur Fraunhofer fur Arbeit Management und Organisation (IAO). [9] A. Carneiro. The role of intelligent resources in knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2001, 5(4): 358367. [10] R. Chase. The knowledge-based organization: An international survey. Journal of Knowledge Management, 1997, 3849. [11] S. Chong, Y. Choi. Critical factors in the successful implementation of knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, 2005, 6. Available at http://www.tlainc.com/jkmp.htm (accessed on July 15, 2007).

MSEM email for subscription: info@msem.org.uk

150

M. Singh & R. Kant: Knowledge management barriers

[12] A. Chua. Knowledge management system architecture: a bridge between km consultants and technologists. International Journal of Information Management, 2004, 24: 8798. [13] K. Dalkir. Knowledge Management in Theory and Practice. Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann., Burlington. [14] T. Devenport, S. Volpel. The rise of knowledge towards attention management. Journal of Knowledge Management, 5(3): 212221. [15] R. Ebert, R. Grifn. Business Essential, 5th edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2005. [16] I. Goll, N. Johnson, A. Rasheed. Knowledge capability, strategic change, and rm performance: The moderating role of the environment. Management Decision, 2007, 45(2): 161 179. [17] D. D. C. Group. Research & perspectives on todays knowledge landscape. in: Delphi on Knowledge Management, Boston, MA (USA), 1997. [18] A. Hariharan. Knowledge management: A strategic tool. Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, 2002, 3. Available at http://www.tlainc.com/jkmp.htm (accessed on March 5, 2007). [19] A. Hariharan. Knowledge management at bharti tele-ventures - a case study. Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, 2005, 6. Available at http://www.tlainc.com/jkmp.htm (accessed on July 15, 2007). [20] W. Jager, R. Straub. Knowledge resources use - results of an inquiry. Personalwirtschaft, 1999, 26(7): 2023. (in German). [21] B. Lemken, H. Kahler, M. Rittenbruch. Sustained knowledge management by organizational culture. in: Proc. of the 33rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 2000, 64. [22] G. Levett, M. Guenov. A methodology for knowledge management implementation. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2000, 4(3): 258269. [23] J. Liebowitz. Knowledge management handbook. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL, 1999. [24] A. Mandal, S. Deshmukh. Vendor selection using interpretive structural modeling (ism). International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 1994, 14(6): 5259. [25] B. Martin. Knowledge based organizations: Emerging trends in local government in australia. Journal of Knowledge Management Practice, 2000. Available at http://www.tlainc.com/jkmp.htm (accessed on July 15, 2007). [26] D. Mason, D. Pauleen. Perceptions of knowledge management: a qualitative analysis. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2003, 7(4): 3842. [27] A. McCampbell, L. Clare, S. Gitters. Knowledge management: the new challenge for the 21st century. Journal of Knowledge Management, 1999, 3(3): 172179. [28] I. Nonaka, H. Takeuchi. The Knowledge-creating Company. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 1995. [29] G. Parkin. Knowledge managing the retirement brain drains. 2005. Available at http://parkinslot.blogspot.com/2005/06/knowledge-managing-retirement-brain.html (accessed on October, 15, 2007). [30] A. Riege. Three-dozen knowledge-sharing barriers managers must consider. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2005, 9(3): 1835. [31] A. Sage. Interpretive Structural Modeling: Methodology for Large-scale Systems, 91164. McGraw-Hill, New York, 1977. [32] T. Sensky. Knowledge management. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 2002, 8: 387396. [33] M. Singh, R. Kant. Knowledge management as competitive edge for indian engineering industries. in: Proc. of the International Conference on Quality and Reliability, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2007, 398403. 5-7 November , pp. 398-403, 2007a. [34] M. Singh, R. Kant. Knowledge management enablers: An interpretive structural modeling approach. in: Proc. of the 8th European Conference on Knowledge Management, Barcelona, Spain, 2007, 915923. 6-7 September, pp. 915-923, 2007 b. [35] M. Singh, R. Narain, R. Kant. Critical factors for successful implementation of knowledge management: An interpretive structural modeling approach. in: Proc. of International conf. on Innovation and Knowledge Management of Social and Economic Issues: International Perspective, J.N.U., New Delhi, India, 2007. January 9-12. [36] M. Singh, R. Shankar, etc. Survey of knowledge management practices in indian manufacturing industries. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2006, 10(6): 110128. [37] J. Wareld. Developing interconnection matrices in structural modeling. IEEE Transactionsons on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, 2005, 4(1): 8167. [38] K. Wiig. Knowledge management foundations-thinking about thinking-how people and organizations create, represent, and use knowledge. Schema Press Arlington, Texas, 1995. [39] R. Witt. Making sense of portal pandemonium. KM Magazine, 1999, 3753. [40] K. Wong, E. Aspinwall. Characterizing knowledge management in the small business environment. Journal of Knowledge Management, 2004, 8(3): 4461. [41] S. Zyngier. Knowledge management obstacles in australia. in: Proc. of the 10th European Conference on Information Systems, Gdansk, Poland, 2002, 919928. June 6-8, pp. 919-928, 2002.

MSEM email for contribution: submit@msem.org.uk

Вам также может понравиться

- Knowledge Management Barriers: An Interpretive Structural Modeling ApproachДокумент11 страницKnowledge Management Barriers: An Interpretive Structural Modeling ApproachAziz MalikОценок пока нет

- IJMET - 10!02!091 Knowledge Management ReadinessДокумент10 страницIJMET - 10!02!091 Knowledge Management ReadinessMarcel YapОценок пока нет

- Knowledge ManagementДокумент8 страницKnowledge ManagementUrmilaAnantОценок пока нет

- Knowledge Architecture Framework Based On ZachmanДокумент4 страницыKnowledge Architecture Framework Based On ZachmanEditor IJRITCCОценок пока нет

- Knowledge Management Model For Construct PDFДокумент9 страницKnowledge Management Model For Construct PDFCassio ManoelОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Knowledge Management On Organisational PerformanceДокумент22 страницыThe Impact of Knowledge Management On Organisational PerformanceasadqhseОценок пока нет

- 3 7-4 BSCДокумент22 страницы3 7-4 BSCkhmortezaОценок пока нет

- Keywords:: Knowledge Management, Information Technology, Knowledge Management System, Socio-Technical SystemДокумент6 страницKeywords:: Knowledge Management, Information Technology, Knowledge Management System, Socio-Technical SystemnareshОценок пока нет

- 3315 12328 1 PBДокумент7 страниц3315 12328 1 PBNorman SuliОценок пока нет

- A Theoretical Framework For Strategic Knowledge Management MaturityДокумент17 страницA Theoretical Framework For Strategic Knowledge Management MaturityadamboosОценок пока нет

- Investigating Knowledge Management Practices in Software Development Organisations - An Australian ExperienceДокумент23 страницыInvestigating Knowledge Management Practices in Software Development Organisations - An Australian ExperienceHameer ReddyОценок пока нет

- Unit Structure - IДокумент100 страницUnit Structure - IAbhilash K R NairОценок пока нет

- 6572-Article Text-27230-1-10-20200310Документ19 страниц6572-Article Text-27230-1-10-20200310Gonzales AbegailОценок пока нет

- IT Project Management and Virtual TeamsДокумент5 страницIT Project Management and Virtual Teamsfoster66Оценок пока нет

- Chioma MSC Assignment 1 MIS New 2Документ12 страницChioma MSC Assignment 1 MIS New 2Nonsoufo eze100% (1)

- Knowlege Managment Strategies in Public SecotorДокумент12 страницKnowlege Managment Strategies in Public Secotoribrahim kedirОценок пока нет

- Measuring Knowledge Management Readiness in ERP Adopted Organizations: A Case of Iranian CompanyДокумент8 страницMeasuring Knowledge Management Readiness in ERP Adopted Organizations: A Case of Iranian CompanybjorncsteynОценок пока нет

- Module 1 Assignment - Formulating A Knowledge Management Strategy PDFДокумент12 страницModule 1 Assignment - Formulating A Knowledge Management Strategy PDFHernando PangilinanОценок пока нет

- KMPI - Measuring Knowledge Management PerformanceДокумент14 страницKMPI - Measuring Knowledge Management PerformanceAlexandru Ionuţ PohonţuОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Knowledge Management On OrganizationДокумент19 страницThe Impact of Knowledge Management On OrganizationNahur BikeОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S2351978915011506 MainДокумент8 страниц1 s2.0 S2351978915011506 MainPutri DewintariОценок пока нет

- A Web-Based Knowledge Management SystemДокумент6 страницA Web-Based Knowledge Management SystemEditor IJRITCCОценок пока нет

- Technology in Managemnt 2Документ8 страницTechnology in Managemnt 2Elvin BucknorОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Knowledge Management On Organisational PerformanceДокумент23 страницыThe Impact of Knowledge Management On Organisational PerformanceOwusu Ansah BrightОценок пока нет

- Research Paper Performance of KnowledgeДокумент15 страницResearch Paper Performance of Knowledgeapi-3697361Оценок пока нет

- Business Intelligence Success Factors: A Literature Review: Journal of Information Technology ManagementДокумент15 страницBusiness Intelligence Success Factors: A Literature Review: Journal of Information Technology ManagementNaol LamuОценок пока нет

- Barriers To Knowledge Management - A Theoretical Framework and A Review of Industrial CasesДокумент12 страницBarriers To Knowledge Management - A Theoretical Framework and A Review of Industrial CasesrenzocollinsОценок пока нет

- Digital Transformatrion Weekly Discussion Forum 3Документ3 страницыDigital Transformatrion Weekly Discussion Forum 3Milan WeerasooriyaОценок пока нет

- Have Information Technologies Evolved Towards Accommodation of Knowledge Management Needs in Basque SMEs?Документ6 страницHave Information Technologies Evolved Towards Accommodation of Knowledge Management Needs in Basque SMEs?irfanteaОценок пока нет

- Actionable Knowledge Discovery: Mohammad Maqsood, M. Steven Vinil Kumar, C. Bhagya Latha, A. Hemantha KumarДокумент4 страницыActionable Knowledge Discovery: Mohammad Maqsood, M. Steven Vinil Kumar, C. Bhagya Latha, A. Hemantha KumarRakeshconclaveОценок пока нет

- Concept of KM Implementation in OrganizationsДокумент50 страницConcept of KM Implementation in OrganizationsBasri Ismail100% (1)

- The Effect of Knowledge Management On Organizational Performance Through Total Quality ManagementДокумент16 страницThe Effect of Knowledge Management On Organizational Performance Through Total Quality ManagementMeet Sanghvi100% (1)

- ItmДокумент4 страницыItmRaghavendra CОценок пока нет

- StratImpModel PDFДокумент15 страницStratImpModel PDFNur FadhilahОценок пока нет

- Deber 1 Luis NaranjoДокумент19 страницDeber 1 Luis NaranjoLuis NaranjoОценок пока нет

- Using Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) As A Tool For Setting Up Student Teams For Information Technology ProjectsДокумент7 страницUsing Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) As A Tool For Setting Up Student Teams For Information Technology ProjectsSEP-Publisher100% (2)

- Competency Measurement ModelДокумент29 страницCompetency Measurement ModelFrancesco Castagna0% (1)

- Assessing Knowledge Retention in ConstruДокумент18 страницAssessing Knowledge Retention in ConstruJade SemillaОценок пока нет

- Enterprise Architecture Model For Implementation KMSДокумент6 страницEnterprise Architecture Model For Implementation KMSMarcel YapОценок пока нет

- Sustainability 11 00058Документ17 страницSustainability 11 00058Ogi AnugrahhОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2Документ3 страницыChapter 2Reem ShakirОценок пока нет

- Arsrv14 N1 P17 37Документ20 страницArsrv14 N1 P17 37Ikin NoraОценок пока нет

- Strategy Implementation DriversДокумент7 страницStrategy Implementation DriversMohemmad Naseef0% (1)

- Analysis of Knowledge Management Within Five Key AreasДокумент24 страницыAnalysis of Knowledge Management Within Five Key AreaschasОценок пока нет

- Build and Design Knowledge Management System For SДокумент9 страницBuild and Design Knowledge Management System For SAyalew NigatuОценок пока нет

- Communicationsin Computerand Information ScienceДокумент11 страницCommunicationsin Computerand Information SciencelemahbritОценок пока нет

- TQM & KMДокумент5 страницTQM & KMAsalSanjabzadehОценок пока нет

- Chapter Three: Theoretical FrameworkДокумент56 страницChapter Three: Theoretical Frameworkإيمان محمدОценок пока нет

- Integrating Knowledge and Processes in The Learning OrganizationДокумент5 страницIntegrating Knowledge and Processes in The Learning OrganizationBiju ChackoОценок пока нет

- The Evolution of Knowledge Management Systems Needs To Be ManagedДокумент14 страницThe Evolution of Knowledge Management Systems Needs To Be ManagedhenaediОценок пока нет

- Ijiem 271Документ13 страницIjiem 271Jabir ArifОценок пока нет

- IT Governance in Enterprise Resource Planning and Business Intelligence Systems Environment: A Conceptual FrameworkДокумент9 страницIT Governance in Enterprise Resource Planning and Business Intelligence Systems Environment: A Conceptual FrameworkhaslindaОценок пока нет

- Identification of Knowledge Gaps in ApplДокумент9 страницIdentification of Knowledge Gaps in ApplRex S. SiglosОценок пока нет

- Critical Failure Factors in Information System ProjectsДокумент6 страницCritical Failure Factors in Information System ProjectsRafiqul IslamОценок пока нет

- Critical Failure Factors in Information System Projects: K.T. YeoДокумент6 страницCritical Failure Factors in Information System Projects: K.T. YeoAbdullah MelhemОценок пока нет

- Paper 13 IJDMSCL Process DesignДокумент17 страницPaper 13 IJDMSCL Process DesignNagarajanОценок пока нет

- The Utilization of COBIT Framework Withi PDFДокумент8 страницThe Utilization of COBIT Framework Withi PDFWahyuОценок пока нет

- Analysing The Relationship Between IT Governance and Business/IT Alignment MaturityДокумент14 страницAnalysing The Relationship Between IT Governance and Business/IT Alignment MaturityĐoàn Đức ĐềОценок пока нет

- International Journal of Engineering Research and Development (IJERD)Документ9 страницInternational Journal of Engineering Research and Development (IJERD)IJERDОценок пока нет

- Séneca, Ensayos MoralesДокумент488 страницSéneca, Ensayos Moralesserjuto100% (1)

- Stoic PsychoДокумент3 страницыStoic Psychopolz2007Оценок пока нет

- McDonalds and KFC RecipesДокумент1 страницаMcDonalds and KFC RecipesSir Hacks alot100% (2)

- Interpers Commun - ParentsДокумент29 страницInterpers Commun - Parentspolz2007Оценок пока нет

- Explorations in PersonalityДокумент802 страницыExplorations in Personalitypolz2007100% (8)

- Coaching PagiansДокумент19 страницCoaching PagianslucindoОценок пока нет

- Bateson Life StoryДокумент3 страницыBateson Life Storypolz2007Оценок пока нет

- Motivating Healthcare Workers & Changing BehaviorsДокумент10 страницMotivating Healthcare Workers & Changing Behaviorspolz2007Оценок пока нет

- Is andДокумент7 страницIs andpolz2007Оценок пока нет

- Deming Follet TaylorДокумент2 страницыDeming Follet Taylorpolz2007Оценок пока нет

- Understanding Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and Connection TypesДокумент8 страницUnderstanding Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and Connection TypesEL A VeraОценок пока нет

- Automatic Industrial Air Pollution Monitoring System''Документ31 страницаAutomatic Industrial Air Pollution Monitoring System''17-256 Teja swiniОценок пока нет

- RPA IntroductionДокумент15 страницRPA IntroductionfanoustОценок пока нет

- Example To Manually Check and Create EDIFACT Signatures 2022-11-18Документ10 страницExample To Manually Check and Create EDIFACT Signatures 2022-11-18ralucaОценок пока нет

- Cummins - ISL CM850 (2003-06)Документ11 страницCummins - ISL CM850 (2003-06)Elmer Tintaya Mamani0% (1)

- Case Study II - RoffДокумент3 страницыCase Study II - RoffNikhil MaheshwariОценок пока нет

- Project Management Resume ExampleДокумент2 страницыProject Management Resume ExampleGuino VargasОценок пока нет

- UntitledДокумент7 страницUntitledVar UnОценок пока нет

- Form Emsd Ee Ct2B: Fresh Water Cooling Towers Scheme Notification of Completion of Cooling Tower InstallationДокумент3 страницыForm Emsd Ee Ct2B: Fresh Water Cooling Towers Scheme Notification of Completion of Cooling Tower InstallationSimoncarter LawОценок пока нет

- BMW Group BeloM SpecificationenДокумент23 страницыBMW Group BeloM SpecificationencsabaОценок пока нет

- Project SpecificationДокумент8 страницProject SpecificationYong ChengОценок пока нет

- Jeti Telemetry ProtocolДокумент8 страницJeti Telemetry ProtocolAsniex NilОценок пока нет

- Advanced Python Lab GuideДокумент38 страницAdvanced Python Lab GuideNetflix ChatbotОценок пока нет

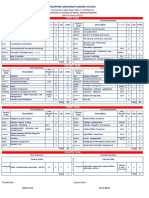

- Philippine Merchant Marine School: First YearДокумент5 страницPhilippine Merchant Marine School: First YearCris Mhar Alejandro100% (1)

- Difference Between ECN, ECR, ECOДокумент3 страницыDifference Between ECN, ECR, ECOmkumarshahiОценок пока нет

- Wheel Loader Air Cleaner Installation Parts ListДокумент4 страницыWheel Loader Air Cleaner Installation Parts ListVladimirCarrilloОценок пока нет

- Nycocrd BrochureДокумент2 страницыNycocrd Brochuremrhrtn88Оценок пока нет

- D500P D510P D520P D530P PDFДокумент30 страницD500P D510P D520P D530P PDFNelson ShweОценок пока нет

- 1/3-Inch 1.2Mp CMOS Digital Image Sensor With Global ShutterДокумент123 страницы1/3-Inch 1.2Mp CMOS Digital Image Sensor With Global ShutteralkrajoОценок пока нет

- Social Media Safety TipsДокумент5 страницSocial Media Safety TipsIthran IthranОценок пока нет

- The Function of Transport TerminalsДокумент3 страницыThe Function of Transport TerminalsRiot Ayase0% (1)

- Siebel 8.1.1 Communications, Media and EnergyДокумент3 страницыSiebel 8.1.1 Communications, Media and EnergyArnaud GarnierОценок пока нет

- Lindapter Uk CatalogueДокумент84 страницыLindapter Uk CataloguemecjaviОценок пока нет

- ArcGIS Tutorials PDFДокумент3 страницыArcGIS Tutorials PDFVaneet GuptaОценок пока нет

- CV Igor Chiriac enДокумент2 страницыCV Igor Chiriac enigorash17Оценок пока нет

- 50 Hydraulics Probs by Engr. Ben DavidДокумент43 страницы50 Hydraulics Probs by Engr. Ben DavidEly Jane DimaculanganОценок пока нет

- TJ 810D 1110D EngДокумент14 страницTJ 810D 1110D EngDavid StepićОценок пока нет

- HCI Designquestions AakashДокумент2 страницыHCI Designquestions Aakashvijay1vijay2147Оценок пока нет

- Ingun Ada Catalogue enДокумент80 страницIngun Ada Catalogue enMichael DoyleОценок пока нет