Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

ISM6022 Pamela Karr and Paul Simpson

Загружено:

Pranab SalianИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

ISM6022 Pamela Karr and Paul Simpson

Загружено:

Pranab SalianАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

ISM6022

Pamela Karr and Paul Simpson

How Process Enterprises Really Work Introduction James Champy, Michael Hammer, and others introduced the concept of Business Process Reengineering (BPR) in the early 1990s. Both Hammer and Champy have authored several books on the subject since then as BPR became a hot buzzword. They now both lead separate consulting practices focusing on helping companies improve their processes. Steve Stanton, coauthor of the article How Process Enterprises Really Work, works with Hammer at his consulting practice. Champy, Hammer, and other proponents of Business Process Reengineering envisioned it to be a fundamental rethinking and radical redesign of business processes to achieve dramatic improvement in critical measures of performance (Management Learning). According to Hammer, a process is everything that transpires from the beginning the point at which a customer or constituent requires something to the point that a customer is satisfied with the results (Harris 1999). A process enterprise is a business that takes the revolutionary concept of BPR and transforms their organization. In the article, How Process Enterprises Really Work, Hammer and Steve Stanton reiterate the importance of building a business around its core processes. They take a look at companies who have successfully applied BPR and became process enterprises, noted some of the obstacles these companies faced and how the obstacles were overcome, and reaffirmed the techniques for becoming a successful process enterprise. After a brief summary of the article, a discussion on why BPR is important and what is necessary to succeed at BPR will follow. To close, some criticisms of BPR, a comparison to other business management techniques such as Six Sigma and Total Quality Management (TQM), and a general recommendation will ensue. Success Stories The success stories that were given in the case all had at least two major themes: BPR was a means to an end for a very specific company initiative, and BPR was faced with much initial resistance by the organizations status quo. For example, Texas Instruments was facing obstacles with lengthy time-to-market and product development times that were being undercut by their competitors. They solved this problem by implementing BPR. BPR enabled them to

ISM6022

Pamela Karr and Paul Simpson

streamline their product development by giving ownership of the development effort to a designated team, thereby getting rid of bottlenecks and enforcing accountability. However, the cross-functional teams were stymied by the existing infrastructure because the old functional departments refused to relinquish their power and give the teams the needed resources for success. Texas Instruments solved this problem by shifting the power from the functional departments to the cross-functional teams. Functional departments became learning centers and budgets were allotted by process instead of department. The end result for Texas Instruments was a 50% time reduction in bringing new products to the market. IBM has a similar story, even though the details are different. IBM found itself competing for the same corporate customers globally, and felt that in order to better serve its customers it would have to standardize its operations worldwide. IBMs obstacles to implementing standardized BPR were the country and product managers who tended to tailor their processes to their region or product. To combat this, IBM reorganized its management structure. Each process was given to a Corporate Executive Committee and a Business Process Executive (BPE) to shift the power from the unit managers. This way, unit managers and BPEs were forced to collaborate when a conflict arose over standardizing a process or allowing it to be tailored for special circumstances. IBMs success came with a $9 billion cost saving, a 75% decrease in the time to market for new products, and increased overall customer satisfaction. The story for Owens Corning began with the initiative to implement an Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system. Since ERP systems tie together previously isolated departments and the people working in them (Hammer 1999) by offering an integrated system with a variety of functional modules and a common backend database, Hammer insisted that a proper ERP implementation could not be done without integrated processes. Owens Cornings problem was that departmental and regional managers were rejecting the integrated software and trying to keep their applications as customized as possible. Owens Corning, like Texas Instruments and IBM, had to reorganize around processes in order to successfully implement the ERP system, which saved them millions of dollars in logistics and administrative costs along with a 50% increase in inventory turns (Hammer & Stanton 1999). Duke Power, an energy company increasingly affected by deregulation, realized that in order to compete it would have to radically modify its business practices and improve customer service.

ISM6022

Pamela Karr and Paul Simpson

They implemented BPR by balancing power between the four regional vice presidents and five new core process owners. Their struggle in defining the clear split in authority was solved by developing a decision rights matrix which outlined which process owner or regional vice president had the jurisdiction to make decisions, which had to be consulted about decisions, and which had to be notified of the outcome. An example of the success that they were able to achieve was the Deliver Products and Services process owners ability to meet 98% of his construction commitments (Hammer & Stanton 1999). Why BPR? In the late 1980s and early 1990s many top executives feared that their companies would be overtaken by more efficient foreign competition or local startups. Its becoming an absolute requirement for companies in almost every business to either rethink or die (Harris 1999). BPR was originally conceived as a way for large, established companies to reorganize themselves around their customers needs, and in doing so become more efficient and improve quality. The key to BPR is the radical redesign of business processes for dramatic improvement (Harris 1999). Radical is a key word here, and the thinking is that the business processes at many established businesses are woefully broken. The business may be surviving or even thriving despite its broken processes, but it could do so much better with a completely redesigned set of processes. BPR eschews incremental change in favor of completely ripping out the old system and starting with a clean slate. As such, its not easy to implement. It requires a lot of foresight and planning, but Hammer and Stanton are convinced that companies who successfully implement BPR will reap the rewards, which include lower costs, higher quality products and services, increased customer satisfaction and loyalty, and greater market share. Those that do not will flounder and lose ground to their more efficient competition. They will waste time and energy on political infighting which should be spent on better serving their customers needs. Unfortunately, as one might expect with such a radical procedure, BPR is very difficult to successfully implement. Stanton and Hammer provide some insights for how to implement BPR more smoothly and with less pain.

ISM6022

Pamela Karr and Paul Simpson

Formula for Success Place respected, high-level executives in process owner roles A company must have the support of lower-level employees for a successful BPR revolution. An effective reengineering leader must be one part visionary, one part communicator, and one part legbreaker (Rotman). If employees respect the individuals who are championing the change, then they will be more likely to embrace the change themselves. Hammer defines a process owner as having three primary tasks: designing, coaching, and advocating (Finley). Process owners must design the process, train employees on the process, and provide all the resources that are necessary for the process to succeed. BPR is usually enforced from the top-down, which can cause much resentment within the lower levels of a company (Rotman). BPR also has been synonymous with mass layoffs at several companies, although it doesnt have to involve any layoffs at all. Thus, it is important to find ways to eradicate the cynicism and have employees buy into the BPR revolution. A process enterprise must have process owners willing and able to promote the benefits of the process throughout the organization (Hammer & Stanton 1999). Put responsibility and authority of a processes success upon the process owner If the process owner does not wield control over the process, the power will ultimately slip back into the hands of the functional departments (Hammer & Stanton 1999). Connect the process enterprise initiative with other strategic organizational initiatives As seen with Texas Instruments, IBM, Duke Power, and Owens Corning, the BPR process did not start on its own. BPR was driven by the companies need to meet a certain goal. Tying BPR to a strategic objective provides a line of sight for management and employees, better enabling them to understand why the change needs to occur (Hammer & Stanton 1999). Tie measurements and compensation to process goal initiatives Using Historical financial data to manage your company is like trying to drive while looking in the rearview mirror (Randomhouse). Just as a BPR initiative needs to be connected to an overarching strategic initiative, companies need to devise a model that ties processes back to these overall performance goals (Randomhouse). If performance compensation is still tied to the functional departments, this will foster internal competition and make it harder for the departments to collaborate to serve the customer (Hammer & Stanton 1999).

ISM6022

Pamela Karr and Paul Simpson

Determine the right blend of process standardization and diversification In this case, IBM decided that it needed to have highly standardized processes in order to compete in a global market. On the other hand, American Standard allowed each of its major business units to create their own process designs. The benefits of standardized processes come from reduced overhead and transaction costs along with the ability to present a consistent front to suppliers and customers. It also allows versatile movement of human resources within an organization since processes are standardized and no additional training is required. However, not all processes can be standardized. The main focus of BPR is on the customers needs. Since different customers have different needs, not all processes can be standardized. Process standardization seeks to balance the desire for consistent processes and the need to meet a variety of customer needs (Hammer & Stanton 1999). Focus on collaboration between functional areas and process teams - The companies mentioned in the article and many other traditional organizations have historically been structured around functional or regional departments that perform discrete tasks. These departments are one of the main barriers to a successful process enterprise. The problem is horizontal processes and vertical management. The departments are often unwilling to give up their internal power to help the process teams succeed. The power needs to be shifted from the functional or regional areas, such as in the case of Texas Instruments and Duke Power, so that there is collaboration between the process owners and the business units. Hammer and Stanton propose that the functional departments still control the workforce and make sure the human resources have the necessary skills, but the process owners have the authority to set performance targets and establish budgets. The cooperation between the business units and process teams should have a tangible manifestation as well. Since cross-functional teams will be working together, it does not make sense to have them sitting with their respective departments. Hammer and Stanton propose that facilities should be set aside to foster cooperation between team members by their physical proximity (1999). Allow processes to be flexible to further evolution BPR is not just a one time deal. It should remain an active goal in an organization ready to adapt as business needs change (Hammer & Stanton 1999).

ISM6022

Pamela Karr and Paul Simpson

Criticism Even Hammer himself admits that only 30 percent [of companies] achieve the kinds of performance breakthroughs they had hoped for (Finley). Indeed, Hammer who has been labeled the Father of Reengineering still vehemently defends BPR and the process enterprises 11 years after his groundbreaking innovation. However, his counterpart, Champy, repudiated BPR in 1994 with his book Reengineering Management because of its cold, scientific approach to transforming an organization. Instead, Champy focuses on the importance of management leadership within an organization. In the name of management science, Hammer failed to address the human side of corporate change (Hammer 1996). BPR, itself, has no major flaws as a model for organizing businesses, but it works better in theory than in practice. Two of the major criticisms of BPR are that it is a euphemism for downsizing and that implemented change on the scale that BPR demands is inherently too difficult. BPR expects functional managers and process owners to work together in a close, collaborative way that most high-level executives find uncomfortable (Context Magazine 2002). Since human behavior is so hard to change, this only increases the chances that a BPR project will fail. Hammer estimates that 80% of an organization will resist process centering at the beginning of a BPR project. However, his only solutions are to win the rest of the organization over through evangelism or cut them loose (Finley). This could be where downsizing became associated with BPR. Although Hammer argues that reengineering eliminates work, not people or jobs, the fact that people are laid-off when jobs are obliterated cannot be denied (Rotman). The scope of change required with BPR can be overwhelming, and this is probably the single biggest fault of BPR. It asks companies to do too much, too quickly. They must convert their employees to this new brand of thinking, re-train their employees to work in new ways, design and implement entirely new ways of performing internal functions, all while continuing to operate their core business. It is little wonder that many companies have been disappointed with the results they have seen and others have vastly underestimated the time, expense, and effort required to reengineer their processes. For BPR to be successful, so many things must fall into place that companies who are considering BPR must be realistic and be honest with themselves as to whether they have the resources to successfully pull it off. If they truly are being realistic, a

ISM6022

Pamela Karr and Paul Simpson

large percentage of companies would have to admit that they may be better off incorporating incremental process changes rather than wholesale reengineering. Alternatives and Recommendations No one has said it better than Hammer himself: If some guru tries to sell you a magic bullet technique that will fix all your problems . . . let the buyer beware (Randomhouse). Although Hammer wants companies to believe that process reengineering is the only way to survive in a competitive environment, he often fails to recognize that there are other management techniques such as Six Sigma and Total Quality Management that have been implemented and proven successful for many companies. The fundamental objective of the Six Sigma methodology is the implementation of a measurement-based strategy that focuses on process improvement and variation reduction (Six Sigma). Total Quality Management is very similar to Six Sigma, but lacks the comprehensive statistical measures of Six Sigma. Another methodology, called Kaizen, is from the same school of incremental improvement as Six Sigma and TQM. Hammers argument against these incremental improvement approaches in that they try to pave the cow path or improve the performance of a process that is flawed (MITSloan). Even so, an incremental improvement on a flawed process may make the process less flawed, something that is surely desirable. If its not possible for a company to completely reengineer its processes, an incremental improvement is better than doing nothing at all. Hammer erroneously states that Six Sigma assumes that the existing design is fundamentally sound (MITSLoan). However, Six Sigma has two branches, one of which can be applied to processes that are broken. Six Sigma DMAIC (define, measure, analyze, improve, and control) deals with existing processes. However, Six Sigma DMADV (define, measure, analyze, design, and verify) deals with new processes and can be applied to those processes that need to be rethought (Six Sigma). Not all processes are broken beyond repair. Many companies such as GE (Six Sigma) and Toyota (Kaizen), have implemented incremental improvement techniques and have found success. A process enterprise does not always have to have revolutionary business process reengineering to dominate the market. In fact, the costs may be too high to do this. A recommendation to any company considering improving its processes is to first closely analyze its current processes, then determine if they should be incrementally or drastically improved, and

ISM6022

Pamela Karr and Paul Simpson

then decide the right mix of management science and art to apply for success. Even if they should decide that a process can be drastically improved and that BPR could be used, companies should be cautious and consider whether the right factors are in place for successful implementation. If not, adopting an incremental approach could be far more profitable in the long run than undertaking a massive BPR approach and possibly running the company into the ground in the process.

ISM6022

Pamela Karr and Paul Simpson

Bibliography Context Magazine. (re)made U.S.A. December 2001/January 2002.

http://www.contextmag.com/setFrameRedirect.asp?src=/archives/200112/Feature0RemadeintheUSA.asp

Finley, Michael. Its Hammer Time! http://www.mastersforum.com/archives/hammer/hammerf.htm Hammer, Michael. Out of the Box: Up on the ERP Revolution. February 1999.

http://www.informationweek.com/720/hammer.htm

Hammer, Michael. Reengineered Recycled. How the Process Centered Organization Is Changing Our Work and Our Lives. August 1996.

http://www.businessweek.com/1996/34/b348940.htm

Hammer, Michael and Stanton, Steven. How Process Enterprises Really Work. November 1999 Harris, Blake. Reengineering and Beyond: The Path to Mutually Enlightened Self Interest. November 1999. http://www.govetech.net/magazine/visions/nov99vision/hammer/hammer.phtml ManagementLearning.com. James Champy and Michael Hammer.

http://managementlearning.com/ppl/chamjame.html

MITSloan Management Review. Process Management and the Future of Six Sigma. Winter 2002. http://mitsloan.mit.edu/smr/past/2002/smr4322.html Randomhouse.com. A conversation with Michael Hammer.

http://www.randomhouse.com/crown/business/ex_archive/ex_hammer.html

Rotman.utoronto.ca. Book Reviewed: Michael Hammer and Steven A. Stanton. The Reengineering Revolution. http://www.rotman.utoronto.ca/~wensle/reviews/bprrev8.htm Six Sigma. Six Sigma What is Six Sigma? January 2001.

http://www.isixsigma.com/sixsigma/six_sigma.asp

Вам также может понравиться

- Reengineering the Corporation (Review and Analysis of Hammer and Champy's Book)От EverandReengineering the Corporation (Review and Analysis of Hammer and Champy's Book)Оценок пока нет

- Business Process Mapping: How to improve customer experience and increase profitability in a post-COVID worldОт EverandBusiness Process Mapping: How to improve customer experience and increase profitability in a post-COVID worldОценок пока нет

- Reengineering of Recruitment and Selection Process in DesconДокумент8 страницReengineering of Recruitment and Selection Process in DesconKaleem MiraniОценок пока нет

- Cause and Impact of BPRДокумент12 страницCause and Impact of BPRMarcela ValdesОценок пока нет

- Business Process Reengineering (BPR)Документ4 страницыBusiness Process Reengineering (BPR)Osama Bin AnwarОценок пока нет

- Business Process ReengineeringДокумент2 страницыBusiness Process Reengineeringsgaurav_sonar1488Оценок пока нет

- Business Process Re-EngineeringДокумент26 страницBusiness Process Re-Engineeringapi-386063075% (4)

- Business Process Reengineering: Teguh I Santoso, MBAДокумент38 страницBusiness Process Reengineering: Teguh I Santoso, MBANagunuri SrinivasОценок пока нет

- Business Process ReДокумент23 страницыBusiness Process ReHarrison NchoeОценок пока нет

- CAMI Article On ABCДокумент21 страницаCAMI Article On ABCDoxCak3Оценок пока нет

- Business Process ReengineeringДокумент10 страницBusiness Process ReengineeringNeha MittalОценок пока нет

- Introduction - BPRДокумент16 страницIntroduction - BPRTejal1212Оценок пока нет

- A BPR Case Study at HoneywellДокумент16 страницA BPR Case Study at HoneywellAbdullah KhanОценок пока нет

- Business Process OrientationДокумент3 страницыBusiness Process Orientationrags01045943Оценок пока нет

- Final Business Process Reengineering.Документ24 страницыFinal Business Process Reengineering.trushna190% (1)

- BPR - A Consolidated Approach by Tushar J. ParakhДокумент5 страницBPR - A Consolidated Approach by Tushar J. ParakhTushar ParakhОценок пока нет

- Reengineering The Corporation: Michael Hammer and James ChampyДокумент33 страницыReengineering The Corporation: Michael Hammer and James Champyssuri20Оценок пока нет

- BPR Case HoneywellДокумент15 страницBPR Case Honeywellravi5dipuОценок пока нет

- Business Process Re-EngineeringДокумент3 страницыBusiness Process Re-Engineeringgaurav bhadoriaОценок пока нет

- BPR or ERP What Comes First PDFДокумент5 страницBPR or ERP What Comes First PDFA-Raouf MahmoudОценок пока нет

- BPR Students Slides Chapter 1Документ26 страницBPR Students Slides Chapter 1Souvik BakshiОценок пока нет

- Business Process Re-Engeering Intro.Документ52 страницыBusiness Process Re-Engeering Intro.hasanuОценок пока нет

- Process Improvement Project GuideДокумент19 страницProcess Improvement Project GuideChris RessoОценок пока нет

- Business Process ReegineeringДокумент4 страницыBusiness Process ReegineeringShariffОценок пока нет

- 1Документ25 страниц1Safalsha BabuОценок пока нет

- Business Process OrientationДокумент13 страницBusiness Process OrientationUdjos JosephОценок пока нет

- Amanure ASSIGNMENT ON TheoryДокумент12 страницAmanure ASSIGNMENT ON TheoryMuhe TubeОценок пока нет

- Business Process Re-Engineering Is The Analysis and Design of Workflows and Processes WithinДокумент8 страницBusiness Process Re-Engineering Is The Analysis and Design of Workflows and Processes WithinShaik AkramОценок пока нет

- BPR (Business Process Reengineering)Документ7 страницBPR (Business Process Reengineering)gunaakarthikОценок пока нет

- BPR MethodologiesДокумент19 страницBPR MethodologiesgunaakarthikОценок пока нет

- Gaining Competitive Advantage Through Human Resource Management PracticesДокумент15 страницGaining Competitive Advantage Through Human Resource Management PracticesSasha KingОценок пока нет

- Business Process ReengineeringДокумент6 страницBusiness Process ReengineeringigoeneezmОценок пока нет

- Business Process Re-EngineeringДокумент23 страницыBusiness Process Re-Engineeringgaurav triyarОценок пока нет

- FACT Project ReportДокумент71 страницаFACT Project ReportMegha UnniОценок пока нет

- Business Process Re EngineeringДокумент2 страницыBusiness Process Re EngineeringVishal PandharkarОценок пока нет

- Business Process Re-Engineering: Angelito C. Descalzo, CpaДокумент28 страницBusiness Process Re-Engineering: Angelito C. Descalzo, CpaJason Ronald B. GrabilloОценок пока нет

- Business Process ReengineeringДокумент13 страницBusiness Process ReengineeringkiranaishaОценок пока нет

- Re Engineering ProcessДокумент28 страницRe Engineering ProcessHeeral ShahОценок пока нет

- Business Process Re-EngineeringДокумент13 страницBusiness Process Re-EngineeringZОценок пока нет

- R1813a '22' AshutoshДокумент13 страницR1813a '22' AshutoshashbasotraОценок пока нет

- Quintano Alfred PDFДокумент14 страницQuintano Alfred PDFRobertson E. MumbohОценок пока нет

- BPR Cib 3401 ModuleДокумент32 страницыBPR Cib 3401 ModuleGILBERT KIRUIОценок пока нет

- BPR Session 1Документ24 страницыBPR Session 1Vinit DawaneОценок пока нет

- Q20 PMC Exam QuestionДокумент2 страницыQ20 PMC Exam Questionapi-3695734100% (1)

- Business Process ReengineeringДокумент10 страницBusiness Process ReengineeringTanay VekariyaОценок пока нет

- Unit 5Документ14 страницUnit 5PrasadaRaoОценок пока нет

- Topic 2Документ20 страницTopic 2neyom bitvooОценок пока нет

- Project Report Re-Engineering and Lessons For Job AnalysisДокумент14 страницProject Report Re-Engineering and Lessons For Job AnalysisMany_Maryy22Оценок пока нет

- Continuous Assessment 31 January 2022. Department of Information Systems Course: Ifs 413 - Business Process ReengineeringДокумент35 страницContinuous Assessment 31 January 2022. Department of Information Systems Course: Ifs 413 - Business Process ReengineeringToby TeddyОценок пока нет

- Erp 3rd Assignment - Susanta RoyДокумент9 страницErp 3rd Assignment - Susanta RoySusanta RoyОценок пока нет

- Business Process ReengineeringДокумент5 страницBusiness Process Reengineeringபாவரசு. கு. நா. கவின்முருகுОценок пока нет

- How Enterprise Really WorkДокумент1 страницаHow Enterprise Really WorkRoman TselobanovОценок пока нет

- Applying Business Process Reengineering To Small and Medium Scale Enterprises SMES in The Developing World.Документ13 страницApplying Business Process Reengineering To Small and Medium Scale Enterprises SMES in The Developing World.Innocent MapinduОценок пока нет

- Business Process RearrangingДокумент7 страницBusiness Process RearrangingMathijs91Оценок пока нет

- 4 Production MagementДокумент2 страницы4 Production Magementsouhila47metliliОценок пока нет

- Business Process Reengineering - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaДокумент4 страницыBusiness Process Reengineering - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaardianekoyatmonoОценок пока нет

- Corporate Restructuring and Its Effect On Employee Morale and PerformanceДокумент9 страницCorporate Restructuring and Its Effect On Employee Morale and PerformanceAbhishek GuptaОценок пока нет

- CORPORATE PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT: An Innovative Strategic Solution For Global CompetitivenessДокумент9 страницCORPORATE PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT: An Innovative Strategic Solution For Global CompetitivenessBabu GeorgeОценок пока нет

- HBR's 10 Must Reads on Strategy (including featured article "What Is Strategy?" by Michael E. Porter)От EverandHBR's 10 Must Reads on Strategy (including featured article "What Is Strategy?" by Michael E. Porter)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (25)

- Cut Costs, Grow Stronger : A Strategic Approach to What to Cut and What to KeepОт EverandCut Costs, Grow Stronger : A Strategic Approach to What to Cut and What to KeepРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Palghar DivisionДокумент2 страницыPalghar DivisionPranab SalianОценок пока нет

- IIML APSL BrochureДокумент17 страницIIML APSL BrochurePranab SalianОценок пока нет

- Creating Product Roadmaps - Roles and Responsibilities GuidanceДокумент10 страницCreating Product Roadmaps - Roles and Responsibilities GuidancePranab SalianОценок пока нет

- Patent Office NoticeДокумент2 страницыPatent Office NoticePranab SalianОценок пока нет

- How To Develop and Construct An Investment PhilosophyДокумент104 страницыHow To Develop and Construct An Investment PhilosophyPranab SalianОценок пока нет

- Link in Trading Pause As Dye & Durham Returns With Part OfferДокумент4 страницыLink in Trading Pause As Dye & Durham Returns With Part OfferPranab SalianОценок пока нет

- Anti-Phishing (DMARC) Webinar RBI IndiaДокумент10 страницAnti-Phishing (DMARC) Webinar RBI IndiaPranab SalianОценок пока нет

- FR TextДокумент1 страницаFR TexthiОценок пока нет

- ETA DetailsДокумент4 страницыETA DetailsPranab Salian100% (1)

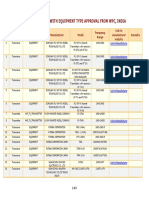

- WPCДокумент37 страницWPCPranab SalianОценок пока нет

- FedexrДокумент2 страницыFedexrPra ChiОценок пока нет

- Housing Society Electricity Meter Connection Transfer NOC No Objection CertificateДокумент1 страницаHousing Society Electricity Meter Connection Transfer NOC No Objection CertificatePranab Salian82% (11)

- Life Cycle of Innovation in Surgery Project OutlineДокумент1 страницаLife Cycle of Innovation in Surgery Project OutlinePranab SalianОценок пока нет

- Implementng Structured Approaches To Innovation - From Theory To PracticeДокумент5 страницImplementng Structured Approaches To Innovation - From Theory To PracticePranab SalianОценок пока нет

- Lean - Theory To PracticeДокумент4 страницыLean - Theory To PracticePranab SalianОценок пока нет

- Virtually Anywhere Lesson Plan Episodes 1 and 2Документ6 страницVirtually Anywhere Lesson Plan Episodes 1 and 2Elyelson dos Santos GomesОценок пока нет

- DSP Manual Autumn 2011Документ108 страницDSP Manual Autumn 2011Ata Ur Rahman KhalidОценок пока нет

- Advanced Java SlidesДокумент134 страницыAdvanced Java SlidesDeepa SubramanyamОценок пока нет

- French DELF A1 Exam PDFДокумент10 страницFrench DELF A1 Exam PDFMishtiОценок пока нет

- Research Methods SESSIONS STUDENTS Abeeku PDFДокумент287 страницResearch Methods SESSIONS STUDENTS Abeeku PDFdomaina2008100% (3)

- PhantasmagoriaДокумент161 страницаPhantasmagoriamontgomeryhughes100% (1)

- ABAP Performance Tuning Tips and TricksДокумент4 страницыABAP Performance Tuning Tips and TricksEmilSОценок пока нет

- Chimney Design UnlineДокумент9 страницChimney Design Unlinemsn sastryОценок пока нет

- Pts English Kelas XДокумент6 страницPts English Kelas XindahОценок пока нет

- Vmod Pht3d TutorialДокумент32 страницыVmod Pht3d TutorialluisgeologoОценок пока нет

- Qualifications: Stephanie WarringtonДокумент3 страницыQualifications: Stephanie Warringtonapi-268210901Оценок пока нет

- Nina Harris Mira Soskis Thalia Ehrenpreis Stella Martin and Lily Edwards - Popper Lab Write UpДокумент4 страницыNina Harris Mira Soskis Thalia Ehrenpreis Stella Martin and Lily Edwards - Popper Lab Write Upapi-648007364Оценок пока нет

- Peranan Dan Tanggungjawab PPPДокумент19 страницPeranan Dan Tanggungjawab PPPAcillz M. HaizanОценок пока нет

- TOS Physical ScienceДокумент1 страницаTOS Physical ScienceSuzette De Leon0% (1)

- SmartForm - Invoice TutorialДокумент17 страницSmartForm - Invoice TutorialShelly McRay100% (5)

- 20 Issues For Businesses Expanding InternationallyДокумент24 страницы20 Issues For Businesses Expanding InternationallySubash RagupathyОценок пока нет

- Ibrahim Kalin - Knowledge in Later Islamic Philosophy - Mulla Sadra On Existence, Intellect, and Intuition (2010) PDFДокумент338 страницIbrahim Kalin - Knowledge in Later Islamic Philosophy - Mulla Sadra On Existence, Intellect, and Intuition (2010) PDFBarış Devrim Uzun100% (1)

- Ervina Ramadhanti 069 Ptn17aДокумент12 страницErvina Ramadhanti 069 Ptn17aMac ManiacОценок пока нет

- The FlirterДокумент2 страницыThe Flirterdddbbb7Оценок пока нет

- Design of Power Converters For Renewable Energy Sources and Electric Vehicles ChargingДокумент6 страницDesign of Power Converters For Renewable Energy Sources and Electric Vehicles ChargingRay Aavanged IIОценок пока нет

- How To Install Windows Drivers With Software Applications: August 1, 2006Документ12 страницHow To Install Windows Drivers With Software Applications: August 1, 2006Mohamad Lutfi IsmailОценок пока нет

- استخدام الشبكة الإدارية في السلوك القيادي بحث محكمДокумент22 страницыاستخدام الشبكة الإدارية في السلوك القيادي بحث محكمsalm yasmenОценок пока нет

- Diamondfreezemel32r E82eenДокумент11 страницDiamondfreezemel32r E82eenGILI RELIABILITYОценок пока нет

- 3D CL Correction S1223RTLДокумент7 страниц3D CL Correction S1223RTLakatsuki.exeОценок пока нет

- Waqas Ahmed C.VДокумент2 страницыWaqas Ahmed C.VWAQAS AHMEDОценок пока нет

- Evidence DoctrinesДокумент5 страницEvidence DoctrinesChezca MargretОценок пока нет

- STIers Meeting Industry ProfessionalsДокумент4 страницыSTIers Meeting Industry ProfessionalsAdrian Reloj VillanuevaОценок пока нет

- CV HuangfuДокумент5 страницCV Huangfuapi-297997469Оценок пока нет