Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

ACCURATELY DETERMINING ECONOMIC RATES OF RETURN

Загружено:

Urvashi RoongtaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

ACCURATELY DETERMINING ECONOMIC RATES OF RETURN

Загружено:

Urvashi RoongtaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

ACCURATELY DETERMINING ECONOMIC RATES OF RETURN FOR THE FINANCING OF LARGE-SCALE EMERGING MARKET DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS Introduction Many

private party large-scale development projects in emerging-market nations have been funded by or received loan guarantees from multilateral organizations such as The United Nations Development Project (UNDP), The African Development Bank (AfDB), The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and The World Bank (WB) through its private sector arm, the International Finance Corporation (IFC). The WBs ultimate goal is to provide economic development for these nations with the hope that this development will lead to the reduction and eventual eradication of poverty.

When assessing the impact of a project on the development of a nation, the IFC uses a metric referred to as the countrys Economic Rate of Return (ERR). ERR calculations take into account all stakeholders of a project the project financiers (whose return is captured in the private return, or financial rate of return (FRR)), the financiers employees, the projects suppliers & customers, producers of complementary goods, competitors of the project (and new entrants into that market), neighboring residents affected by the implementation of the project, and the rest of society. ERR determination focuses more on the efficiency of resource allocation and therefore treats each group equally. By choosing to evaluate ERR this way, one has to question whether the objectives of the multilateral agencies is met. If the objective of the organizations is the eradication of poverty, should more weight not be placed on the value of the project to the neighboring community (and

to local suppliers) and less emphasis given to the project financiers (who are already compensated via the FRR)?

ERR Framework Currently The Economic Rate of Return (ERR) can loosely be defined as The net benefits to all members of society, as a percentage of cost, taking into account externalities and other market imperfections. In a Harvard Business School Professor Benjamin Esty defined a two-step process for calculating an Economic Rate of Return. This method is described briefly thus: ERR = Actual Revenues Opportunity Costs = Actual Revenues Opportunity Costs + (Actual Costs Actual Costs) = (Actual Revenues Actual Costs) + (Actual Costs Opportunity Costs) ERR = Private Returns + Cost Gains.. (1) where Private Returns = Actual Revenues Actual Costs Cost Gains = Actual Costs Opportunity Costs This simple calculation assumes the exclusion of taxes and other social anomalies.

The analysis presented above highlights the fact that there is a difference between Private and Social Returns. Though the difference between opportunity costs and actual costs is the only difference noted above, other reasons for this difference could include: Taxes, Tariffs and other forms of Government intervention which could reduce private returns; Transaction Costs; and Non-market effects such as the impact of the project on the environment.

In addition to highlighting the differences between the ERR and the FRR (or social returns and private returns), the analysis also shows, through the gains in costs, that investments in large-scale projects should result in economic development. Why is this not always the case? Rather than giving equal weight to FRR and Opportunity Costs in the determination of Social Returns, less emphasis should be placed on private returns, and more significance should be placed on other stakeholders who are likely to receive more economic benefit from the project.

Social Returns: Who Are the Other Stakeholders? Exhibit 1 is a diagram that shows the interaction of the stakeholders of a large-scale investment project. Aside from the project financiers, the other stakeholders and their interests are: EMPLOYEES: This group experiences 2 major benefits 1) wages over and above the opportunity cost of labor and 2) training that could be valuable to other employers CUSTOMERS: The project provides 3 major benefits to customers, including: 1) the provision of a novel good or service, 2) a better quality of an existing type of product or service, and 3) an increase in the supply of a particular good or service, which could lead to price reduction. PRODUCERS OF COMPLEMENTS: The producers of complements are likely to benefit from the fact that an increase in the products production of a particular good will likely result in the increased sale of complementary goods.

SUPPLIERS: By choosing to supply their wares to the project firm, local suppliers will benefit positively from the project.

COMPETITORS: Though competition will intensify if the good provided by the project is similar to an existing market, society benefits, as a whole, as the price paid for the good or service will be lower. By contrast, if a project requires a certain type of input from a supplier that can be used by other entities, the increased demand for this input (due to competition) could result in a price increase, which would result in a benefit to the supplier and thus society as a whole.

NEIGHBORS: Perhaps the most important of all stakeholders, the neighboring community stands to benefit positively and negatively from the project existence. Positive benefits include improved infrastructure and basic services such as schools, medical facilities and community centers. However, the environment is likely to be affected. Although there could be some positive environmental impacts, the likelihood is that this will not be the case (problems such as oil spills and air pollution can result depending on the nature of the project).

The FRR certainly cannot be excluded from the determination of social returns. The private investor assumes a number of risk factors (Exhibit 2) when investing in a developing nation, and those risks need to be accounted for. In addition, according to Dr. John Ohiorhenuan, the Deputy Director of the UNDPs Crisis and Prevention Bureau, If it were not for the private party seeing an avenue to make a profit, there would be no project to invest in in the first place. The private investor

creates the vehicle for social development. So you cannot discount his value.

This statement is true the private investor does create the vehicle for economic development when investing in large-scale projects. However, he seeks a financial profit for himself and social benefit is usually not a primary concern to him. The stated objective of the UNDP and other multilateral organizations is the reduction of poverty and promotion of sustainable development in developing nations. As such, in determining social returns, more emphasis should be given to the parties who stand to benefit most from increased income and social development: the neighboring community, some local suppliers, and indigenous people hired by the project.

Accounting for Income Inequality: Lorenz Curves and The Gini Coefficient Developed by Max Lorenz in 1905, the Lorenz curve is an efficient means of representing income inequality within a country (Exhibit 3). The curve shows the relationship between the cumulative percentage of actual income received and the percentage of the population that received the particular income. Building on this, the Italian mathematician Corrado Gini, in his paper Variabilit e mutabilit published in 1912, defined a relation (the Gini coefficient) which is defined as the area between the Lorenz curve of a probability distribution function and the curve of a uniform distribution probability distribution function to the total area under the uniform distribution curve. Gini coefficients range between 0 (meaning that no inequality exists in the income of a nation) to 1 (implying perfect income inequality). Exhibit 4 shows the Gini coefficient for select nations.

Mathematically, the Gini coefficient can be represented as:

Gy = 2 cov Y , F ( y ) y

(2)

where = mean income F(y) = normalized rank of a household in the distribution of income

In his paper entitled Benefit Incidence Analysis on Public Sector Expenditures in Ethiopia: the case of Education and Health, Michael Seifu combined the Gini coefficient with the mean national income to define a social welfare function:

W = Y (1 G y ) . (3)

Social Returns can be calculated by applying equation (1) above. However, by slightly modifying equation (1) to be of the form ERR = Private Returns + {1+ [1-(ln (W)/10]}*Cost Gains . (4) multilateral organizations can require a higher ERR for projects, with the additional gains being realized by the lower-income stakeholders (i.e., not the private investors). A higher Economic Rate of Return does not necessarily mean that the lower income stakeholders will receive additional economic benefit. However, the higher ERR could force private investors into realize the necessity of investing not only for his own financial return, but also for the benefit of the local economy of the project region. In addition, this simple framework does not address such issues as government expropriation and mismanagement of funds (such as was observed after the IFCs investment in the Chad-

Cameroon Pipeline Project), but this can be rectified by modifying the function to emphasize improving returns to the necessary stockholders.

Exhibit 1. Stakeholder Diagram

Customers Producers of Complimentary Products Financiers (FRR) Neighbors Employees

Rest of Society

Competitors & New Entrants

Suppliers

Source: Benjamin Esty, Frank Lysy, & Carrie Ferman, An Economic Framework for Assessing Development Impact, Harvard Business School Case 9-202-052.

Exhibit 2. List of Potential Risk Factors faced by Project Financiers 1) Sovereign Risk: a. Direct Currency Risk b. Indirect Currency Risk c. Expropriation i. Direct ii. Diversion iii. Creeping d. Multilateral Agency Involvement e. Sensitivity of Project to wars, strikes, etc f. Sensitivity of Project to natural disasters 2) Operating Risk: a. Resource Risk b. Technology Risk 3) Financial Risk: a. Probability of default b. Political Risk Insurance

Source: Campbell Harvey, Country Risk Worksheet

10

Exhibit 3. The Lorenz Curve and the Gini Coefficient

Cumulative % of Income

Uniform PDF Curve

o iC e

t i en c ffi

n Gi

Lorenz Curve

% of Population receiving Income

11

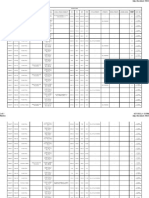

Exhibit 4. Human Development Statistics for Select (Low Development) Nations

MDG Share of income or consumption (%) HDI rank 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 Madagascar Swaziland Cameroon Lesotho Djibouti Yemen Mauritania Haiti Kenya Gambia Guinea Senegal Nigeria Rwanda Angola Eritrea Benin Cte d'Ivoire Tanzania, U. Rep. of Malawi Zambia Survey year 2001 1994 2001 1995 .. 1998 2000 .. 1997 1998 1994 1995 1996 1983 .. .. .. 2002 1993 1997 1998 e e e e e e e e e e e e e c e e Poorest 10% 1.9 1.0 2.3 0.5 .. 3.0 2.5 .. 2.5 1.8 2.6 2.6 1.6 4.2 .. .. .. 2.0 2.8 1.9 1.0 Poorest 20% 4.9 2.7 5.6 1.5 .. 7.4 6.2 .. 6.0 4.8 6.4 6.4 4.4 9.7 .. .. .. 5.2 6.8 4.9 3.3 Richest 20% 53.5 64.4 50.9 66.5 .. 41.2 45.7 .. 49.1 53.4 47.2 48.2 55.7 39.1 .. .. .. 50.7 45.5 56.1 56.6 Richest 10% 36.6 50.2 35.4 48.3 .. 25.9 29.5 .. 33.9 37.0 32.0 33.5 40.8 24.2 .. .. .. 34.0 30.1 42.2 41.0 Richest 10% to poorest 10% 19.2 49.7 15.7 105.0 .. 8.6 12.0 .. 13.6 20.2 12.3 12.8 24.9 5.8 .. .. .. 16.6 10.8 22.7 41.8 Inequality measures Richest 20% to poorest 20% 11.0 23.8 9.1 44.2 .. 5.6 7.4 .. 8.2 11.2 7.3 7.5 12.8 4.0 .. .. .. 9.7 6.7 11.6 17.2

Gini index 47.5 60.9 44.6 63.2 .. 33.4 39.0 .. 42.5 47.5 40.3 41.3 50.6 28.9 .. .. .. 44.6 38.2 50.3 52.6

12

167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177

Congo, Dem. Rep. of the Mozambique Burundi Ethiopia Central African Republic Guinea-Bissau Chad Mali Burkina Faso Sierra Leone Niger

.. 1996 1998 1999 1993 1993 .. 1994 1998 1989 1995 e e e e e e e e e

.. 2.5 1.7 3.9 0.7 2.1 .. 1.8 1.8 0.5 0.8

.. 6.5 5.1 9.1 2.0 5.2 .. 4.6 4.5 1.1 2.6

.. 46.5 48.0 39.4 65.0 53.4 .. 56.2 60.7 63.4 53.3

.. 31.7 32.8 25.5 47.7 39.3 .. 40.4 46.3 43.6 35.4

.. 12.5 19.3 6.6 69.2 19.0 .. 23.1 26.2 87.2 46.0

.. 7.2 9.5 4.3 32.7 10.3 .. 12.2 13.6 57.6 20.7

.. 39.6 33.3 30.0 61.3 47.0 .. 50.5 48.2 62.9 50.5

13

References 1) Benjamin Esty, Frank Lysy, & Carrie Ferman, An Economic Framework for Assessing Development Impact, Harvard Business School Case 9-202-052, February 7, 2003. 2) Philip LeBel, PhD., Economic Analysis of Development Projects, Center for Economic Research on Africa, Montclair State University, Spring 2003. 3) Michael Seifu, Benefit Incidence Analysis on Public Sector Expenditures in Ethiopia: The Case of Education & Health. 4) Benjamin Esty, Frank Lysy, & Carrie Ferman, Nghe An Tate & Lyle Sugar Company (Vietnam), Harvard Business School Case 9-202-054, May 27, 2003 5) Benjamin Esty, Frank Lysy, & Carrie Ferman, Teaching Note: Nghe An Tate & Lyle Sugar Company (Vietnam), Harvard Business School Case 9-202-067, June 12, 2003 6) Benjamin Esty & Aldo Sesia Jr., An Overview of Project Finance 2004 Update, Harvard Business School Case 9-202-065, April 29, 2005. 7) Campbell Harvey, Aditya Agarwal, & Sandeep Kaul, Project Finance Introduction. 8) New York Department of Transportation Handbook of Economic Development, Elements of Economic Analysis of Projects.

14

Вам также может понравиться

- Crowdfunding For Impact in Europe and The USAДокумент24 страницыCrowdfunding For Impact in Europe and The USACrowdfundInsiderОценок пока нет

- Project Analysis of Urban Planning Master's ProjectДокумент28 страницProject Analysis of Urban Planning Master's ProjectHarita SalviОценок пока нет

- Financial Markets Fundamentals: Why, how and what Products are traded on Financial Markets. Understand the Emotions that drive TradingОт EverandFinancial Markets Fundamentals: Why, how and what Products are traded on Financial Markets. Understand the Emotions that drive TradingОценок пока нет

- Sky vs BSB payoff matrix analysisДокумент3 страницыSky vs BSB payoff matrix analysisd-fbuser-46026705100% (1)

- Benefit Cost Analysis HandoutДокумент16 страницBenefit Cost Analysis HandoutGemma P. TabadaОценок пока нет

- Tata Consultancy Services PayslipДокумент2 страницыTata Consultancy Services PayslipNilesh SurvaseОценок пока нет

- Discuss The UNIDO Approach of Social-Cost Benefit AnalysisДокумент3 страницыDiscuss The UNIDO Approach of Social-Cost Benefit AnalysisAmi Tandon100% (1)

- Strauss Printing ServicesДокумент5 страницStrauss Printing ServicesYvonne BigayОценок пока нет

- Topic 6 - Concepts of National Income (Week5)Документ52 страницыTopic 6 - Concepts of National Income (Week5)Wei SongОценок пока нет

- How Should We Think About Debt Capital Markets Today? ESG’s Effect On DCMОт EverandHow Should We Think About Debt Capital Markets Today? ESG’s Effect On DCMОценок пока нет

- Daro Nacar Vs Gallery Frames DigestДокумент4 страницыDaro Nacar Vs Gallery Frames DigestMyra MyraОценок пока нет

- Efficiency, Effectiveness and Performance of Public SectorДокумент16 страницEfficiency, Effectiveness and Performance of Public Sectorfreya4u100% (1)

- Economic, Social and Environmental Cost Benefit AnalysisДокумент5 страницEconomic, Social and Environmental Cost Benefit AnalysisProfessor Tarun DasОценок пока нет

- PM - Social Cost Benefit AnalysisДокумент6 страницPM - Social Cost Benefit AnalysisEkta DarganОценок пока нет

- Project Appraisal SCBAДокумент15 страницProject Appraisal SCBAapi-3757629100% (1)

- Chapter 6 &7Документ6 страницChapter 6 &7demeketeme2013Оценок пока нет

- Chapter 005 PMДокумент5 страницChapter 005 PMHayelom Tadesse GebreОценок пока нет

- Chapter 4 and 5 Project AbДокумент77 страницChapter 4 and 5 Project Abnigus gurmis1Оценок пока нет

- Unit-3 SCBAДокумент7 страницUnit-3 SCBAPrà ShâñtОценок пока нет

- Social Cost-Benefit Analysis: Submitted To Doctor GetnetДокумент15 страницSocial Cost-Benefit Analysis: Submitted To Doctor GetnetSamuel DebebeОценок пока нет

- Social Cost-Benefit Analysis: Chapter SixДокумент29 страницSocial Cost-Benefit Analysis: Chapter SixAbebe GetanehОценок пока нет

- Social Cost-Benefit Analysis InsightsДокумент5 страницSocial Cost-Benefit Analysis InsightsIsrael Ad FernandoОценок пока нет

- Social Cost Benefit Analysis (SCBA) : By: Narayan GaonkarДокумент24 страницыSocial Cost Benefit Analysis (SCBA) : By: Narayan GaonkarusmanОценок пока нет

- Project Ass From Mek ModuleДокумент19 страницProject Ass From Mek Modulesamuel kebedeОценок пока нет

- Social Cost and Benefit AnalysisДокумент9 страницSocial Cost and Benefit AnalysisAmi Tandon100% (1)

- Project Finance: Economic Framework For Assessing Development ImpactДокумент13 страницProject Finance: Economic Framework For Assessing Development ImpactPriyanshu Sharma FIN01Оценок пока нет

- ScbaДокумент9 страницScbasambam500Оценок пока нет

- Agricultural EconomicsДокумент45 страницAgricultural EconomicsMilkessa SeyoumОценок пока нет

- Social Cost Benefit AnalysisДокумент11 страницSocial Cost Benefit Analysisdwivedi25100% (7)

- SCBA Project Case Study PDFДокумент22 страницыSCBA Project Case Study PDFrishipathОценок пока нет

- Social Cost Benefit AnalysisДокумент10 страницSocial Cost Benefit Analysismuskan5jain-9Оценок пока нет

- UNIT-4 Social Cost Benefit Analysis (Scba)Документ8 страницUNIT-4 Social Cost Benefit Analysis (Scba)javed alamОценок пока нет

- Chapter 3Документ30 страницChapter 3Tadese MulisaОценок пока нет

- Keywords: Social Cost Benefit Analysis-UNIDO Approach, Coal Plant, Hydro Plant, PowerДокумент22 страницыKeywords: Social Cost Benefit Analysis-UNIDO Approach, Coal Plant, Hydro Plant, PowerVidya Hegde KavitasphurtiОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2 Financial Analysis and Appraisal of Project 21Документ24 страницыChapter 2 Financial Analysis and Appraisal of Project 21kasuОценок пока нет

- Regional Social Accounting ImpactsДокумент6 страницRegional Social Accounting ImpactscarolsaviapetersОценок пока нет

- Three Approaches to Economic Analysis of ProjectsДокумент25 страницThree Approaches to Economic Analysis of ProjectsRodrick WilbroadОценок пока нет

- Social Cost Benefit AnalysisДокумент4 страницыSocial Cost Benefit AnalysisNazmus ShakibОценок пока нет

- Online Annex 2.1. Financing Constraints and The Strategy For InvestmentДокумент47 страницOnline Annex 2.1. Financing Constraints and The Strategy For InvestmentVdasilva83Оценок пока нет

- Social Cost Benefit Analysis (SCBA) ExplainedДокумент12 страницSocial Cost Benefit Analysis (SCBA) ExplainedAli KhanОценок пока нет

- Cost-Benefit Analysis Guide (40 CharactersДокумент20 страницCost-Benefit Analysis Guide (40 Charactersdavid56565Оценок пока нет

- Identifying Costs and Benefits in Agricultural ProjectДокумент64 страницыIdentifying Costs and Benefits in Agricultural Projectwondater MulunehОценок пока нет

- How To Note Efa Part 2 MethodsДокумент25 страницHow To Note Efa Part 2 Methodsancadinu22Оценок пока нет

- Cost-Benefit Analysis Framework for Evaluating Public ProjectsДокумент23 страницыCost-Benefit Analysis Framework for Evaluating Public ProjectsPooja GuptaОценок пока нет

- Finteo (2) (Vseborec cz-f33sx)Документ25 страницFinteo (2) (Vseborec cz-f33sx)Matej HaraslínОценок пока нет

- Social Cost Benefit Analysis ExplainedДокумент3 страницыSocial Cost Benefit Analysis ExplainedTemesgenОценок пока нет

- ScbaДокумент30 страницScbaDeepika SharmaОценок пока нет

- Social Cost Benefit AnalysisДокумент67 страницSocial Cost Benefit Analysisitsmeha100% (1)

- Investment For African Development: Making It Happen: Nepad/Oecd Investment InitiativeДокумент37 страницInvestment For African Development: Making It Happen: Nepad/Oecd Investment InitiativeAngie_Monteagu_6929Оценок пока нет

- CONCORD Aidwatch Input To OECD-DAC Senior Level Meeting - 3-4 March 2014Документ6 страницCONCORD Aidwatch Input To OECD-DAC Senior Level Meeting - 3-4 March 2014OECD PublicationsОценок пока нет

- "National Income": A Project Report OnДокумент39 страниц"National Income": A Project Report OnSaidas KavdeОценок пока нет

- Challenges For European Welfare Systems PDFДокумент10 страницChallenges For European Welfare Systems PDFar15t0tleОценок пока нет

- Principles Underlying The Economic Analysis of ProjectsДокумент29 страницPrinciples Underlying The Economic Analysis of ProjectsArmando RodasОценок пока нет

- PM MBA 6, 7Документ28 страницPM MBA 6, 7Tedros AbrehamОценок пока нет

- Unit-3 Social Cost Benefit AnalysisДокумент13 страницUnit-3 Social Cost Benefit AnalysisPrà ShâñtОценок пока нет

- TD D0 BOOHWi KLF 4 YP93Документ25 страницTD D0 BOOHWi KLF 4 YP93Mohamed MustefaОценок пока нет

- Econ Analysis of ProjectsДокумент91 страницаEcon Analysis of ProjectsBarkhad MohamedОценок пока нет

- Eficienta Si EficacitateДокумент16 страницEficienta Si EficacitateMaria HergheligiuОценок пока нет

- Financial Exclusion Costs QuantifiedДокумент10 страницFinancial Exclusion Costs QuantifiedVictoriaWokabiОценок пока нет

- PUBLIC POLICY AND ANALYSIS (IGNOU) Unit-20Документ14 страницPUBLIC POLICY AND ANALYSIS (IGNOU) Unit-20Vaishnavi SuthraiОценок пока нет

- Microfinance PaperДокумент9 страницMicrofinance PaperAnnaSОценок пока нет

- SFM Handwritten Notes 3Документ56 страницSFM Handwritten Notes 3Raul KarkyОценок пока нет

- A Radical Solution for the Problems of Bankruptcy and Financial Bottlenecks for Individuals and CompaniesОт EverandA Radical Solution for the Problems of Bankruptcy and Financial Bottlenecks for Individuals and CompaniesОценок пока нет

- Report of the Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development 2020: Financing for Sustainable Development ReportОт EverandReport of the Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development 2020: Financing for Sustainable Development ReportОценок пока нет

- Rexercises 1 R BasicДокумент35 страницRexercises 1 R BasicJohn StephenОценок пока нет

- Building XML Web Services With PHP NusoapДокумент12 страницBuilding XML Web Services With PHP NusoapUrvashi RoongtaОценок пока нет

- Informatica Mapping Variable AssignmentДокумент7 страницInformatica Mapping Variable AssignmenttungarajaОценок пока нет

- JasperServer Admin GuideДокумент98 страницJasperServer Admin GuideAnurag Wazalwar100% (1)

- The World Trade Organization... : ... in BriefДокумент8 страницThe World Trade Organization... : ... in BriefDiprajSinhaОценок пока нет

- Wipro Annual ReportДокумент212 страницWipro Annual ReportJuzar HusainОценок пока нет

- CH 02Документ3 страницыCH 02Osama Zaidiah100% (1)

- Ch05-Accounting PrincipleДокумент9 страницCh05-Accounting PrincipleEthanAhamed100% (2)

- Capacity To ContractДокумент33 страницыCapacity To ContractAbhay MalikОценок пока нет

- ACCT212 - Financial Accounting - Mid Term AnswersДокумент5 страницACCT212 - Financial Accounting - Mid Term AnswerslowluderОценок пока нет

- Blank Finance Budgets and Net WorthДокумент24 страницыBlank Finance Budgets and Net WorthAdam100% (6)

- Finnifty Sum ChartДокумент5 страницFinnifty Sum ChartchinnaОценок пока нет

- MGL IPO Note | Oil & Gas SectorДокумент16 страницMGL IPO Note | Oil & Gas SectordurgasainathОценок пока нет

- Preparing Financial StatementsДокумент6 страницPreparing Financial StatementsAUDITOR97Оценок пока нет

- Hussein Abdullahi Elmi: Personal ProfileДокумент3 страницыHussein Abdullahi Elmi: Personal ProfileHusseinОценок пока нет

- Black Money-Part-1Документ9 страницBlack Money-Part-1silvernitrate1953Оценок пока нет

- FX Risk Hedging and Exchange Rate EffectsДокумент6 страницFX Risk Hedging and Exchange Rate EffectssmileseptemberОценок пока нет

- Common Bank Interview QuestionsДокумент23 страницыCommon Bank Interview Questionssultan erboОценок пока нет

- Complaint Versus Jeffrey Christian MabilogДокумент3 страницыComplaint Versus Jeffrey Christian MabilogManuel MejoradaОценок пока нет

- Engineering EconomyДокумент18 страницEngineering EconomyWesam abo HalimehОценок пока нет

- Bankruptcy of Lehman BrothersДокумент12 страницBankruptcy of Lehman Brothersavinash2coolОценок пока нет

- Buy Back Article PDFДокумент12 страницBuy Back Article PDFRavindra PoojaryОценок пока нет

- PT Ever Shine Tex Annual Report HighlightsДокумент122 страницыPT Ever Shine Tex Annual Report HighlightsKhairul UmamОценок пока нет

- Internship Report On "General Banking, Investment Mode & Foreign Exchange Activities of Al-Arafah Islami Bank Limited"Документ84 страницыInternship Report On "General Banking, Investment Mode & Foreign Exchange Activities of Al-Arafah Islami Bank Limited"Rayhan Zahid Hasan100% (1)

- Public-Private Partnerships: Shadrack Shuping Sipho KabaneДокумент8 страницPublic-Private Partnerships: Shadrack Shuping Sipho Kabaneasdf789456123Оценок пока нет

- HKSI LE Paper 11 Pass Paper Question Bank (QB)Документ10 страницHKSI LE Paper 11 Pass Paper Question Bank (QB)Tsz Ngong KoОценок пока нет

- Budgetary Control - L G ElectonicsДокумент86 страницBudgetary Control - L G ElectonicssaiyuvatechОценок пока нет

- AUSTRALIAN WOOLLEN MILLS PTY LTD V COMMONWEA PDFДокумент17 страницAUSTRALIAN WOOLLEN MILLS PTY LTD V COMMONWEA PDFjohndsmith22Оценок пока нет

- LNS 2018 1 2016Документ26 страницLNS 2018 1 2016Aini RoslieОценок пока нет

- Power of Compounding CalculatorДокумент5 страницPower of Compounding CalculatorVinod NairОценок пока нет