Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Consolidated Reply-Aff (FB)

Загружено:

Romulo UrciaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Consolidated Reply-Aff (FB)

Загружено:

Romulo UrciaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

2

Affidavit is not properly verified or subscribed under oath in accordance with law.

1.1

The

Counter-Affidavit contains a

of

private

respondent but the

Gapangada

verification

verification is patently defective. It does not comply with the requirement of the rule on verification because it does not contain the required attestation that allegations therein are true and correct of his personal knowledge or based on authentic records. The body of the Counter-Affidavit of private respondent Gapangada is also completely bereft of any allegation attesting that the allegations therein are true and correct of his personal knowledge. Neither is there any statement in the body of his Counter-Affidavit attesting to the veracity of the contents of his Counter-Affidavit.

1.2

Section 4 of Rule 7 of the 1997 Rules of Civil procedure explicitly provides for the rule on verification, to quote: Section 4 of Rule 7 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure provides: SEC. 4. Verification. Except when otherwise specifically required by law or rule,

pleadings need not be under oath, verified or accompanied by affidavit. A pleading is verified by an affidavit that the affiant has read the pleadings and that the allegations therein are true and correct of his personal knowledge or based on authentic records. A pleading required to be verified which contains a verification based on information and belief or upon knowledge, information and belief or lacks a proper verification, shall be treated as an unsigned pleading. (Emphasis ours)

1.3

In Negros Oriental Planters Association, Inc. vs. Hon. Presiding Judge of RTC-Negros Occidental, Branch 52, Bacolod City,1 the Supreme Court declared that A pleading, therefore, wherein the Verification is merely based on the partys

knowledge and belief produces no legal effect xxx.

1.4

Obedience to the requirements of procedural rules is needed if we are to expect fair results therefrom, and utter disregard of the rules cannot justly be rationalized by harking on the policy of liberal construction. Time and again, this Court has

strictly enforced the requirement of verification and certification of non-forum shopping under the

1

G.R. No. 179878, December 24, 2008.

Rules of Court. This case is no exception. Verification is required to secure an assurance that the allegations of the petition have been made in good faith, or are true and correct and not merely speculative.2 (Emphasis ours)

1.5

We would not have objected to the defective verification of the Counter-Affidavit of private respondent Gapangada if only the body of his Counter-Affidavit contains a statement or allegation attesting to the veracity of the contents of his Counter-Affidavit but, as mentioned above, this attestation is also manifestly wanting in his CounterAffidavit.

1.6

Without the allegation in the verification that the allegations in his Counter-Affidavit are true and correct of his personal knowledge or based on authentic records, or without any statement in the body of his Counter-Affidavit attesting to the veracity of the contents thereof, then there is no assurance that the allegations in the Counter-

Clavecilla vs. Quitain, G.R. No. 147989, February 20, 2006, citing Mariveles Shipyard Corp. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 144134, November 11, 2003, 415 SCRA 573, 584; Pagtalunan v. Manlapig, G.R. No. 155738, August 9, 2005; Torres v. Specialized Packaging Development Corp., G.R. No. 149634, July 6, 2004, 433 SCRA 455, 464.

Affidavit of private respondent Gapangada have been made in good faith, or are true and correct and not merely speculation. In other words, there is no assurance that the contents of the CounterAffidavit of respondent Gapangada are not false and purely speculative. Thus, it is only proper that the Counter-Affidavit of private respondent

Gapangada should be treated as unsigned pleading which produces no legal effect.

2.

Private respondent Gapangada contends in his Counter-

Affidavit that a private individual, like himself, cannot be held criminally liable for violation of Section 3 (g) of R.A. No. 3019, otherwise known as the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, by citing the ruling of the Supreme Court in the case of Go vs. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 172602 in its Resolution dated September 3, 2007. This contention of private respondent Gapangada is quite misleading and it distorted the final ruling of the Supreme Court in the said case of Go vs. Sandiganbayan.

2.1

In its subsequent Resolution dated April 16, 2009, the Supreme Court had overturned/reversed its Resolution dated September 3, 2007 in Go vs. Sandiganbayan when it ruled that private

individuals may be charged in conspiracy with public officer for violating Section 3(g) and if found guilty, be held liable therefore, to quote: We maintain that to be indicted of the offense under Section 3(g) of R.A. No. 3019, the following elements must be present: (1) that the accused is a public officer; (2) that he entered into a contract or transaction on behalf of the government; and (3) that such contract or transaction is grossly and manifestly disadvantageous to the government. However, if there is an allegation of conspiracy, a private person may be held liable together with the public officer, in consonance with the avowed policy of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act which is to repress certain acts of public officers and private persons alike which may constitute graft or corrupt practices or which may lead thereto.3

2.2

In a later case of Santillano vs. Court of Appeals, 4 the Supreme Court reiterated its ruling in the Resolution dated April 16, 2009 in Go vs. Sandiganbayan5 where it was ruled that the fact that one of the elements of Section 3(g) of RA 3019 is that the accused is a public officer does not necessarily preclude its application to private persons who, like petitioner Go, are being charged

3 4

Go vs. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 172602, April 16, 2009. G.R. Nos. 175045-46, March 3, 2010. 5 G.R. No. 172602, April 13, 2007, 521 SCRA 270.

with

conspiring

with

public

officers

in

the The

commission of the offense thereunder.

appellants assertion was at odds with the policy and spirit behind RA 3019, which was to repress certain acts of public officers and private persons alike which constitute graft or corrupt practices or which may lead thereto.6

3.

The instant criminal case for violation of Section 3(g) of

the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act and the corresponding administrative complaint are founded on two (2) legal grounds (a) that the respondents have conspired and confederated with one another in entering into the three (3) water contracts subject matter of the complaint, which contracts are manifestly and grossly

disadvantageous to the Municipality of Majayjay, Laguna (Majayjay for short) because they were entered into by respondents in gross violation of (i) Republic Act No. 6957, as amended by Republic Act No. 7718, otherwise known as the Built-Operate and Transfer Law (BOT Law for short), (ii) Republic Act No. 9184, otherwise known as the Procurement Reform Act, (iii) and the Local Government Code of 1991, and (b) that the subject three (3) water contracts by themselves [ and by going from the body of the contract itself] will

6

Santillano vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. Nos. 175045-46, March 3, 2010.

indubitably

show

that

they

are

manifestly

and

grossly

disadvantageous to Majayjay.

4.

Contrary to the claim of pubic respondents-members of

the Sangguniang Bayan (SB for short), the lack of proper bidding and posting of the required performance security as well as the lack of compliance with either the BOT Law, Executive Order (E.O.) No. 423 dated April 30, 2005, Procurement Reform Act or the Local Government Code of 1991 are relevant and material to the instant case to show that respondents have conspired with one another to enter into a manifestly and gross disadvantageous contract to Majayjay and that public respondents committed grave misconduct and gross negligence in the discharge of their duties.

5.

The aforestated laws were enacted by the legislature to

protect the government and its agencies or instrumentalities, including the LGUs, from onerous and grossly disadvantageous contracts. Since the respondents did not follow those laws in the execution of the subject three (3) water contracts, then the respondents have in effect placed Majayjay in a very onerous and disadvantageous position.

6.

In other words, the public respondents committed grave

misconduct and gross negligence in the discharge of their duties when they conspired with one another to authorize the execution of the subject three (3) water contracts without due observance of the

provisions of those laws. The public respondents should not have authorized the execution of the subject three (3) water contracts without due compliance with the provisions of those laws. In acting otherwise, public respondents should be held not only criminally liable but also administratively liable for grave misconduct and gross negligence in the discharge of their duties.

7.

On the fact that the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT

between Majayjay and Israel Builders and Development Corporation (IBDC) is manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to Majayjay because it violated the BOT Law, the Counter-Affidavit of the respondents will show that they did not dispute and disprove the allegations and proof presented in our Affidavit-Complaint dated June 14, 2012 that the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT has grossly violated the BOT Law. The respondents merely made the lame

excuse that the BOT Law is not applicable to the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT. This lame excuse of respondents cannot prevail over the undisputed fact that the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT involved an unsolicited proposal from IBDC involving important and priority project of Majayjay.

7.1

As an unsolicited proposal from IBDC, the subject BULK

WATER CONTRACT clearly falls within the coverage of the BOT Law but the same was entered into by respondents without the

10

required publication and approval as provided under Sections 4, 5 and 6 of R.A. No. 7718 or the BOT Law.

7.2

More importantly, the term of the said BULK WATER

CONTRACT is contrary to the provision of Section 8 of R.A. No. 7718 which provides that the maximum term of a BOT contract shall not exceed fifty (50) years. But the BULK WATER CONTRACT provides for a mind boggling term of 100 years, inclusive of the 50 years automatic extension.

7.3

Therefore, the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT is

manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to Majayjay because it was entered into by respondents in gross violation of the BOT Law.

8.

Private respondent Gapangada and public respondent

Guera contend that the BOT Law will not apply to the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT and they both cited that the applicable law is the GUIDELINES on Joint Venture (JV) pursuant to Section 8 of Executive Order (E.O.) No. 423 dated April 30, 2005. Public respondent Guera has even the temerity to claim that even the Procurement Reform Act is also not applicable to the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT.

9.

Assuming arguendo without in any way conceding that

the GUIDELINES on JV provided under Section 8 of E.O. 423 dated April 30, 2005 is the applicable law to the subject BULK WATER

11

CONTRACT, still there is a patent violation of the aforestated GUIDELINES because Section 4.0 of E.O. No. 423, sub-paragraph 4.1, explicitly provides that Local Government Units (LGU) are not covered by these Guidelines.

9.1

On the other hand, Section 12 of E.O. No. 423 dated April 30,

2005 explicitly provides that Procurement contracts of local government units, regardless of the source of funds, shall be subject to the provisions of Republic Act No. 9184 and its Implementing Rules and Regulations.

9.2

Since Section 12 of E.O. No. 423 clearly provides that

procurement contracts of LGU, regardless of the source of funds, is subject to the Procurement Reform Act, it follows, therefore, that the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT is subject to the procedures on competitive bidding as provided under the Procurement Reform Act.

9.3

Sad to say, however, respondents entered into and executed the WATER CONTRACT without complying with the

BULK

requirements/procedures on competitive bidding as provided in Procurement Reform Act. Republic Act No. 9184 requires preparation of bidding documents following the standard forms and manuals prescribed by the GPPB, 7 pre-procurement conference,8 advertising of

7 8

Section 17, Republic Act No. 9184. Section 20, Republic Act No. 9184.

12

invitation to bid,9 pre-bid conference,10 eligibility requirements of a prospective bidder shall be made under oath,11 submission of Bids shall have technical and financial components, 12 all Bids shall be accompanied by Bid security,13 opening of all the Bids publicly at a specified date, time and place,14 Bid evaluation,15 post qualification,16 notice of Award,17 and performing security.18

9.4

The respondents Counter-Affidavits are completely bereft of

any allegation and proof showing that the award of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT to IBDC had complied with the aboveenumerated requirements and procedures on competitive bidding as provided under the Procurement Reform Act. The BULK WATER CONTRACT is neither a negotiated procurement as it does not fall to any of the thirteen (13) types of a negotiated procurement applicable in specific and distinct situation enumerated under the Revised Implementing Rules and Regulation of Republic Act No. 9184. Thus, for having been awarded to IBDC in gross violation of Republic Act No. 9184, the BULK WATER CONTRACT is obviously manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to Majayjay.

9

Section 21, Republic Act No. 9184. Section 22, Republic Act No. 9184. 11 Section 23, Republic Act No. 9184. 12 Section 25, Republic Act No. 9184. 13 Section 27, Republic Act No. 9184. 14 Section 28, Republic Act No. 9184. 15 Article IX, Republic Act No. 9184. 16 Article X, Republic Act No. 9184. 17 Section 37, Republic Act No. 9184. 18 Section 39, Republic Act No. 9184.

10

13

10.

On the fact that the subject BULK WATER

CONTRACT is contrary to the Local Government Code of 1991, the respondent did not dispute the fact that the 10% share of Majayjay under the BULK WATER CONTRACT is a public fund. Neither is there a denial from respondents that the BULK WATER CONTRACT provides in Section 7 (b) of its Article IV that the price of water for the first ten (10) cubic meters charged against the concessionaires of Majayjay shall not exceed P30.00 and that the difference between P30.00 and the total of the actual production, distribution and the other operating and maintenance costs plus the agreed rate of return shall be subsidized by the 10% share of Majayjay from the bulk water sales.

10.1

In other words, there is no denial from respondents that said 10% share of Majayjay, which is a public fund, shall be used to subsidize the water concessionaires of Majayjay or the same shall be used to pay for the obligation of private individuals.

10.2

Since the 10% share of Majayjay is a public fund, the same cannot be used without appropriations

ordinance or law. Section 305 (a and b), Chapter I, Title Five of the Local Government Code provides

14

that No money shall be paid out of the local treasury except in pursuance of an appropriations ordinance or law and that Local government funds and monies shall be spent solely for public purposes.

10.3

The Local Government Code further mandates that No public money or property shall be

appropriated or applied for religious or private purposes.19 Thus, the said 10% share of Majayjay cannot be used to subsidize the water concessionaires of Majayjay or to pay the water bills of private individuals. If only the respondents have any intention to protect the interest of Majayjay, respondents should have stipulated in the BULK WATER CONTRACT that the subsidy to water concessionaires of Majayjay should be chargeable against the 90% share of IBDC from the proceeds of the sale of bulk water. But it appears that respondents have no concern at all for the interest of Majayjay as they have conspired and confederated with one another to charge the said subsidy to the meager 10% share of Majayjay.

19

Section 335, Chapter 4, Title Five of the Local Government Code.

15

10.4 By allowing and authorizing the stipulation in the BULK WATER CONTRACT that the 10% share of Majayjay shall be used to subsidize the water concessionaires of Majayjay, respondents have in effect allowed and authorized the use of public funds without appropriations ordinance or law and for private purposes and the same constitutes plain and simple crime of malversation of public funds. Simply put, by authorizing the use of public funds without appropriations ordinance or law and for private purposes, respondents have in effect authorized or abetted the commission of the crime of malversation of public funds. 10.5 It is manifestly and grossly disadvantageous and prejudicial to Majayjay for respondents to allow and authorize under the BULK WATER

CONTRACT the use of public funds [10% share of Majayjay] without appropriations ordinance or law and for private purposes.

11.

Granting arguendo that the subject three (3) water

contracts are not contrary to the BOT Law, Procurement Reform Act and the Local Government Code of 1991, still the same will not

16

exonerate the respondents from the offense charged of violating Section 3(g) of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. This is because the validity of the contract is not indispensable for the prosecution and conviction under Section 3(g) of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act. As held by the Supreme Court in the case of Luciano vs. Estrella20, to require conviction under Section 3(g) of the R.A. 3019 that the validity of the contract or transaction be first proved would be to enervate, if not defeat the intention of the law. For what would prevent the officials from entering into those kinds of transactions against which R.A. 3019 is directed, and then deliberated omit the observance of certain formalities just to provide a convenient leeway to avoid the clutches of the law in the event of discovery and consequent prosecution?

12.

For the prosecution and conviction under Section 3(g) of

the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act, it will be enough to show that the contract itself subject of the criminal action is manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to the government. Such is the situation obtaining in the case at hand. The three (3) water contracts subject matter of the instant case are manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to Majayjay.

20

34 SCRA 769

17

13.

On the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT, the same

is manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to Majayjay because:

13.1

The subject BULK WATER CONTRACT does not provide/indicate any specific PROJECT COST for the project. In fact, the respondents did not deny that there is no PROJECT COST indicated in the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT.

13.2

Without

the PROJECT

COST,

it cannot be

determined the correct amount of performance security that should be posted by IBDC as required under Section 37 of the Procurement Reform Act.

13.3

Without the PROJECT COST, the posting of the required performance security will depend on the whims and caprices of IBDC.

13.4

Without the correct performance security, there is no assurance that IBDC will complete the project.

13.5

Without the correct performance security, there is no assurance that Majayjay would be compensated for damages in the event of default or delay by IBDC in the performance of its contractual obligations under the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT.

18

13.6

Without the PROJECT COST, the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT will be an open-ended contract where the cost of the project will solely depend upon the whims and caprices of IBDC.

13.7

Without the PROJECT COST, the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT will be an open-ended contract where the determination of the Recovery Of Investment (ROI) will solely depend upon the whims and caprices of IBDC.

13.8

Without the PROJECT COST, the return of investment cannot be determined. The determination of return of investment to IBDC is necessary to avoid excessive and unreasonable return of investment. It is worth noting that the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT does not provide for a formula for the return of investment. Thus, Majayjay will have no way of finding whether IBDC has already recovered its investments. Moreso, the 25% ROI provided

under the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT is unconscionable. Jurisprudence dictates that 12% is the just amount of return of investment.

19

13.9

Without the PROJECT COST, it cannot be determined if the term of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT for 50 years or 100 years is reasonable.

13.10

Without the PROJECT COST, there is unnecessary risk exposure to Majayjay as there is no clear provision in the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT on the adjustment of the water rate. Respondents public officers have, in a way, given full authority and discretion to IBDC to

compute and determine any adjustments on water rate. In other words, any adjustments on water rate will solely depend upon the whims and caprices of IBDC which is greatly prejudicial and

disadvantageous not only to Majayjay but, more importantly, to the people of Majayjay.

13.11

The subject BULK WATER CONTRACT exposes Majayjay to unnecessary risks as there is no provision in the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT on the amount to be shouldered as subsidy by Majayjay. In the Bulk Water Contract, respondents public officers agreed that the difference between the P30.00 charged for every household of concessionaire of Majayjay and the total of actual production, distribution and

20

other operating and maintenance cost plus the agreed rate of return shall be subsidized by the Majayjay.21 The subject Bulk Water Contract did not even provide for the ceiling amount that can be subsidized by Majayjay.

13.12

More importantly, the subject Bulk Water Contract does not specify who or what entity is the regulator. It is not an acceptable practice that one and the same entity operates and regulates the supply of basic utilities such as water in this case. In the instant case, it appears that IBDC has the sole authority to operate and even regulate the supply of water. There will be no checks and balances to ensure that the operator does not over-charge and perform its obligation to its clients. Respondent public officers allowed IBDC to exercise such sole authority at the expense of and to the great disadvantage of Majayjay.

13.13

The subject BULK WATER CONTRACT provides for a term of 100 years, inclusive of the 50 years automatic extension, at the revenue sharing of 90% in favor of IBDC and 10% in favor of Majayjay.

21

Section 7 (b), Article IV of the Contract for the Supply of Bulk Water dated August 1, 2011.

21

13.14

The fifty (50) years automatic extension of the contract is not subject to any condition. It is automatically effective as the wording of the contract connotes. The words provided under Section 4 of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT that - unless terminated pursuant to the provisions provided herein is not a condition for the effectivity of the 50 years automatic extension of the contract but the same merely provided for a ground for the termination of the 50 years automatic extension of the contract.

13.15

However, the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT does not have a TERMINATION CLAUSE. Section 29 of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT has nothing to do with the TERMINATION CLAUSE as it does not provide for a ground for the termination of the contract. Thus, the 50 years automatic extension of the contract is absolute and unconditional which makes the term of the contract effective for 100 years.

13.16

The subject BULK WATER CONTRACTs term of 100 years, inclusive of the 50 years automatic

22

extension, is not only illegal but it is also unconscionable and contrary to moral and public policy especially considering the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT does not provide for the PROJECT COST or the investments to infused by IBDC for the project.

13.17

It

is

obviously

grossly

and

manifestly

disadvantageous to Majayjay to give IBDC a term of 100 years under the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT as the same virtually lock up for 100 years in favor of IBDC the right to extract and enjoy the abundant water resources of Majayjay to the great disadvantage and prejudice of Majayjay and its inhabitants.

13.18

The sharing arrangement in the revenue to be generated from the sale of bulk water is in the proportion of ninety percent (90%) in favor of IBDC and ten percent (10%) in favor of Majayjay22. This revenue sharing arrangement is not only disadvantageous to Majayjay but the same is unconscionable especially considering the

22

Section 22, Article XIV of the Contract for the Supply of Bulk Water dated August 1, 2011.

23

respondents have likewise agreed for the allowable 25%23 rate of return in favor of IBDC. These 10% share of Majayjay and the agreed 25% allowable rate of return to IBDC are obviously greatly

disadvantageous to Majayjay.

13.19

The agreed 25% allowable rate of return is unreasonable and unconscionable. It is also contrary to the long established ruling of the Supreme Court that the reasonable rate of return for company engaged in public utility business is only 12%.24

13.20

The said 10% share of Majayjay is disadvantageous and unconscionable because this ten percent (10%) share of Majayjay is still subject to deduction25 on the difference between the P30.00 charged for every household of concessionaire of Majayjay and the total of actual production, distribution and other operating and maintenance costs plus the 25% agreed rate in return.

13.21

In other words, the 10% share of Majayjay from the proceeds of the sale of bulk water is subject to various deductions but the ninety percent (90%) share of

23 24

Section 16 paragraph 5, Article XI of the Contract for the Supply of Bulk Water dated August 1, 2011. Meralco vs. Public Service Commission, 18 SCRA 651; and Republic vs. Meralco, 391 SCRA 700, 709 25 Section 7 (b), Article IV of the Contract for the Supply of Bulk Water dated August 1, 2011.

24

IBDC is not subject to any deduction, except for the 2% intended for tree planting which shall equally be borne by IBDC and Majayjay. Stated otherwise, after charging the said deductions from the 10% share of Majayjay, it is most likely that nothing would be left to Majayjay. Better yet, Majayjay will be holding nothing but empty bag.

13.22

The BULK WATER CONTRACT grants sole and exclusive authority to IBDC to extract water from Mangulila, Patak-Patak, Sinabak Spring, Gundala Springs and the surface water of Dalitiwan River26. On top of it, the Water Contract granted IBDC the right to extract water from all water sources of Majayjay under the principle of right of first refusal27. In other words, by virtue of the Water Contract, IBDC has the sole and absolute control over all water resources of Majayjay, Laguna for the next 100 years or until 2111.

13.23

Stated differently, on account of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT, Majayjay and its residents/ inhabitants would be deprived of the rights to use and

26 27

Section 6 (f), Article IV of the Contract for the Supply of Bulk Water dated August 1, 2011. Section 7 (g), Article IV of the Contract for the Supply of Bulk Water dated August 1, 2011.

25

enjoy all water sources of Majayjay for the next 100 years or until 2111 in favor of IBDC without need of public bidding.

13.24

IBDC was granted the right to extract water from all water sources of Majayjay without payment of any compensation/consideration for the grant of such water right. This is obviously manifestly and grossly prejudicial to Majayjay.

13.25

At this point, it is significant to take note that Majayjay has abundant sources of water as it is situated at the foot of Mt. Banahaw. As we have pointed out in our Affidavit-Complaint dated June 14, 2012, the real purpose of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT is not to rehabilitate the water system of Majayjay but to exploit the abundant water resources in favor of IBDC with practically no cost for IBDC for a period of 100 years at the sharing arrangement of 90% in favor IBDC and only 10% in favor of Majayjay.

13.26

To illustrate the enormous water resources of Majayjay, pursuant to BULK WATER CONTRACT, IBDC filed an application for issuance of water

26

permit

before

the

Laguna

Lake

Development

Authority (LLDA) over the Mangulila Spring located at Brgy. Piit, Majayjay, Laguna. A copy of the application for water permit filed by IBDC before the LLDA is hereto attached for ready reference as Annex A.

13.27

Under the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT, the right to apply for water permit for the various water resources of Majayjay was granted to Majayjay but respondent public officials allowed IBDC to apply water permit on Mangulila Spring as well as on two (2) other springs in Majayjay, to wit: (i) Sinabak Spring and (ii) Patak-Patak Spring. Copies of the applications for water permit by IBDC over Sinabak Spring and Patak-Patak Spring are enclosed hereto as Annexes B and C, respectively.

13.28

In the application for water permit alone of IBDC over Mangulila Spring, IBDC has applied to extract water from Magulila Spring for diversion to the Municipalities of Magdalena, Sta. Cruz and Lumban at the rate of 900 Liters Per Second (LPS) or 54,000 Liters Per Min. or 3,240,000 Liters Per Hour or

27

77,760,000 Liters Per Day. In other words, from Mangulila Spring alone, IBDC will extract water for sale as bulk water at the rate of 77,760,000 Liters Per Day. Thus, from Mangulila Spring alone, IBDC will get and be able to sell bulk water to the neighboring towns at the rate of 77,760,000 Liters Per Day.

13.29

It

is

obviously

manifestly

and

grossly

disadvantageous to Majayjay and its people for respondent public officials to authorize IBDC to extract water from Mangulila Spring and sell the same as bulk water to neighboring towns at the rate of 77,760,000 Liters Per Day.

13.30

Worse, while IBDC was allowed by respondent public officials to extract water from Mangulila Spring and divert it for sale as bulk water to neighboring towns at the rate of 77,760,000 Liters Per Day, the water to be diverted to Majayjay for distribution to its people is only 5,184,000 Liters Per Day, as shown in IBDCs applications for water permit for Sinabak Spring and Patak-Patak Spring. In these two (2) applications for water permits, IBDC

28

will extract water from Sinabak Spring for diversion to Majayjay at the rate of 30 Liters Per Second (LPS) or 1, 800 Liters Per Minute or 108,000 Liters Per Hour or 2,592,000 Liters Per Day, while the water to be extracted from Patak-Patak Spring for diversion to Majayjay will also be at the same rate as the water coming from Sinabak Spring or the combined volume of water coming from Sinabak Spring and PatakPatak Spring for diversion to Majayjay will be 5,184,000 Liters Per Day.

13.31

So, the combined volume of water that will come from Sinabak Spring and Patak-Patak Spring for diversion to Majayjay is only 5,184,000 Liters Per Day, while the volume of water that will come from Mangulila Spring for diversion to the neighboring towns will be 77,760,000 Liters Per Day.

13.32

In other words, the volume of water that will be diverted for distribution to the people of Majayjay is much smaller than the volume of water to be diverted for sale as bulk water to neighboring towns. This goes to show that the real purpose of subject BULK WATER CONTRACT is not the rehabilitation

29

of the water system of Majayjay but to exploit the abundant water resources of Majayjay for sale as bulk water to neighboring towns.

13.33

Simply put, the supposed rehabilitation of the water system of Majayjay is merely a devious scheme employed by respondents to be able to exploit [at practically no cost on the part of IBDC] the abundant water resources of Majayjay for sale as bulk water to neighboring towns. In employing such devious scheme, the respondents have obviously acted in concert to the great prejudice and disadvantage of Majayjay and its people.

13.34

Aside from Mangulila Spring, Sinabak Spring and Patak-Patak Spring, there are other equally abundant water sources in Majayjay which have been placed under the control of IBDC for the next 100 years due to the provision in the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT which provides that IBDC has been granted the right to extract water from all water sources of Majayjay. This provision in the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT is not only grossly

30

disadvantageous to Majayjay but it is immoral, unconscionable and contrary to public policy.

13.35

Most importantly, the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT does not contain any provision

providing that IBDC shall post prior to the execution of the contract performance security to assure compliance with its contractual obligation. In the subject (2) Water Supply Contracts, it is expressly provided therein that Majayjay shall post performance security consisting of 5% cash bond, 10% bank guarantee and 30% surety bond in favor of the Municipality of Sta. Cruz, Laguna and the

Municipality of Lumban, Laguna, respectively. But such important provision on the posting of

performance security was eliminated in the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT which renders the same grossly disadvantageous to Majayjay.

13.36

Private respondent Gapangada claims that IBDC posted surety bond in the sum of P10,000,000.00 for the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT. However, aside from being obviously insufficient, an

examination of the surety bond posted by IBDC will

31

show that the same is not accompanied by the required Certification from Insurance Commissioner with the contents that (i) the bond is for the stated project; (ii) the amount of the bond and (iii) the bond is callable on demand. This Certification is necessary for the validity and effectivity of the surety bond, as shown in the Non Policy Matter (NPM) No. 017-2012 issued by Government Procurement Policy Board (GPPB) hereto attached as Annex D.

13.37

Accordingly, since the alleged surety bond posted by IBDC is not accompanied by the aforesaid required Certification from the Insurance Commissioner, then the said bond is not valid and effective. Necessarily, the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT is without the required performance security which renders it manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to Majayjay.

14.

On the Water Supply Contract28 between Majayjay and

the Municipality of Lumban, Laguna and the Water Supply Contract29 between Majayjay and the Municipality of Sta. Cruz, Laguna, the said two (2) Water Supply Contracts are also manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to Majayjay because:

28 29

Annex L of the Affidavit-Complaint dated June 14, 2012. Annex M of the Affidavit-Complaint dated June 14, 2012.

32

14.1

Under the BULK WATER CONTRACT, it is expressly provided that IBDC shall have the sole right and authority to supply bulk water to Majayjay and the neighboring towns30, including but not limited to Lumban and Sta. Cruz. Since the right and authority to supply bulk water under the BULK WATER CONTRACT belongs to IBDC, then it is only proper that IBDC should be the one to act as the Water Supplier to Lumban and Sta. Cruz but obviously it was not done so as to enable IBDC to evade any and all obligations arising under the subject two (2) Water Supply Contracts.

Respondents have acted in concert to make Majayjay as the Water Supplier and not IBDC. 14.2 As such Water Supplier, Majayjay assumed all the obligations and responsibilities for the supply of bulk water to Lumban and Sta. Cruz, including but not limited to the payment of penalties in the event of default or delay and the posting of the required performance security such as the (i) cash bond equivalent to 5% of the total contract price, (ii) bank

30

Section 7 (a), Article IV of the Contract for the Supply of Bulk Water dated August 1, 2012.

33

guarantee equivalent to 10% of the total annual contract price and (iii) surety bond equivalent to 30% total annual contract price. The purpose of this cash bond, bank guarantee and surety bond is to guarantee the faithful performance by Majayjay of its obligations under the Water Contracts.

14.3

As provided in Section 2 of Article IV of the Water Contract-Lumban31, Majayjay will post for Lumban the performance security equal to the annual contract price. Under the contract, Majayjay shall supply potable water to Lumban at the volume of at least 5,000 cubic meters per day or 150,000 cubic meters per month or 1,825,000 cubic meters for 365 days or one (1) year at the price of P11.00 per cubic meter.

14.4

At the price of P11.00 per cubic meter, the total annual contract price of 1,825,000 cubic meters of water per year is P20,075,000.00. Thus, Majayjay will have to post performance security in favor of Lumban as follows: (i) cash bond of 5% equivalent to the sum of P1,003,750.00, (ii) bank guarantee of 10% equivalent to the sum of P2,007,500.00 and (iii)

31

Annex L of the Affidavit-Complaint dated June 14, 2012.

34

surety bond of 30% equivalent to the

sum of

P6,022,500.00. Simply put, Majayjay will have to post performance security in favor of Lumban in the total sum of P9,033,750.00.

14.5

On the other hand, for Sta. Cruz, Majayjay will have to post performance security equal to the annual contract price of P5,110,000 cubic meters of water per annum at the price of P10.00 per cubic meter. Under the Water Contract-Sta. Cruz 32, Majayjay is obligated to supply potable water to Sta. Cruz at the price of P10.00 per cubic meter and at the rate of at least 14,000 cubic meters per day or 420,000 cubic meters per month or 5,110,000 cubic meters per 365 days or per annum.

14.6

At the volume of 5,110,000 cubic meters per annum at the price of P10.00 per cubic meter, the total annual contract price of the contract of Majayjay with Sta. Cruz for the supply of potable water is P51,100,000.00. Thus, Majayjay will have to post performance security in favor of Sta. Cruz consisting of (i) cash bond 5% equivalent to the sum of

32

Annex M, hereof

35

P2,555,000.00, (ii) bank guarantee of 10% equivalent to the sum of P5,110,000.00 and (iii) surety bond of 30% equivalent to the sum of P15,330,000.00. Simply put, Majayjay will have to post performance security in favor of Sta. Cruz in the total sum of P22,995,000.00.

14.7

In resume, Majayjay will have to post performance security in favor of Lumban equivalent to the total sum of P9,033,750.00, while for Sta. Cruz, Majayjay will post performance security equivalent to the total sum of P22,995,000.00 or Majayjay will post performance security in favor of Lumban and Sta. Cruz in the amount equivalent to the grand total of P32,028,750.00.

14.8

Considering IBDC is not the Water Supplier under the subject two (2) Water Supply Contracts but Majayjay, then IBDC was effectively relieved and released from the obligation to post performance security in favor or Lumban and Sta. Cruz in the amount equivalent to the total sum of P9,033,750.00 and the total sum of P22,995,000.00, respectively.

36

14.9

Respondent

Guera claims

that the right

and

obligations of Majayjay under the subject two (2) Water Supply Contracts will be eventually assigned to IBDC. But the fact remains that to this date Majayjay is the contractual obligor under the subject two (2) Water Supply Contracts.

14.10

In any event, this claim of respondent Guera that the rights and obligations of Majayjay will be eventually assigned to IBDC is a confirmation of the fact that the subject two (2) Water Supply Contracts were purposely entered into by Majayjay with Sta. Cruz and Lumban so as to do away with the required public bidding if IBDC will be the one to act as water supplier.

14.11

Since the two (2) Water Supply Contracts are Negotiated Agency to Agency-Procurement, then the same does not need public bidding. This is the precise contention of private respondent Gapangada. In other words, respondents have made it appear that the subject two (2) Water Supply Contracts is a Negotiated Agency to Agency-Procurement so as to enable IBDC to evade the requirement for public

37

bidding as well as to evade the obligation of posting the required performance security. This kind of irregular and anomalous transaction has placed Majayjay at a grossly disadvantageous situation.

15.

The revision and amendment of the subject BULK

WATER CONTRACT is the best evidence that the same is manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to Majayjay and that respondents have acted in bad faith and in conspiracy with one another to give legal color and justification to a manifestly and grossly disadvantageous contract.

15.1

Respondents

contend

that

the

subject

BULK

WATER CONTRACT is not manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to Majayjay as it was already revised and amended to make as contracting party to it a certain AAA Water Corporation (AAA Water for short). Respondent Guera attached to his CounterAffidavit the Memorandum of Agreement between IBDC and AAA Water in order to bolster his claim that there will be a big funder for the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT as AAA Water is supposedly a big company.

38

15.2

Respondents/members of SB, on the other hand, passed a Resolution Blg. 114 T. 2012 dated June 25, 201233 to confirm and ratify the Memorandum of Agreement between IBDC and AAA Water.

15.3

On the same date of June 25, 2012, respondents SB members passed a Resolution Blg. 115 T. 201234 to authorize the revision and amendment of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT to make part of it AAA Water.

15.4

Consequently, respondent Guera attached to his Counter-Affidavit an alleged Addendum and

Revision to the Contract for the Supply of Bulk Water dated August 1, 201235 where supposed to be IBDC, AAA Water and Majayjay agreed for the revision of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT. The name of AAA Water was indicated in the said Addendum and Revision but an examination of the body of the same will show that AAA Water did not sign or give its consent to the said Addendum and Revision. Thus, it is a big lie for respondents to

33 34

Annex T of the Counter-Affidavit of Public Respondent Guera.. Annex U of the Counter-Affidavit of Public Respondent Guera.. 35 Annex W of the Counter-Affidavit of Public Respondent Guera.

39

claim that there is now a funder for the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT.

15.5

At best, the aforestated Resolutions 36 of respondents SB members and the said Addendum and Revision to the Contract for the Supply of Bulk Water 37 are the best evidence that respondents have acted and are acting in conspiracy with one another to authorize the implementation of an anomalous and unlawful contract Majayjay. which is grossly disadvantageous to

15.6

The aforestated Resolutions of respondent SB members and the said Addendum and Revision to the Contract for the Supply of Bulk Water are mere afterthought by respondents with no other evident intention but to cure or correct a contract void from the beginning.

15.7

It is well worth to stress that our Affidavit-Complaint was filed on June 15, 2012 and it was posted on the Facebook of Gising Majayjay on the same date which makes the same accessible to the general public.

36 37

Annexes T and U of the Counter-Affidavit of Public Respondent Guera. Annex W of the Counter-Affidavit of Public Respondent Guera

40

15.8

Respondents were all duly furnished with copy of our Affidavit-Complaint by registered mail as shown in our Ex-Parte Motion dated June 26, 2012.

Respondents public officials received copy of our said Affidavit-Complaint on June 25, 2012, as shown in the photocopies of the Registry return card attached to our Ex-Parte Motion dated June 26, 2012.

15.9

The Resolution Blg. 114 T-2012 and Resolution Blg. 115 T-2012 were both passed and approved on June 25, 2012 by respondent pubic officials while the aforestated Addendum and Revision to the Contract for the Supply of Bulk Water was executed and signed by IBDC and Majayjay on August 1, 2012.

15.10

From the foregoing, it is quite clear that at the time of the passage by respondents public officials of said Resolution Blg. 114 T-2012 and Resolution Blg. 115 T-2012 as well as at the time of the execution of the said Addendum and Revision, the respondents have already an actual notice and knowledge of our Affidavit-Complaint dated June 14, 2012.

15.11

In other words, respondents have already an actual notice and knowledge of the defects and legal flaws

41

of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT at the time of the passage of said Resolution Blg. 114 T2012 and Resolution Blg. 115 T-2012. This is apparently the reason why respondents public officials passed the said Resolution Blg. 114 T-2012 and Resolution Blg. 115 T-2012 and authorized the execution of the said Addendum and Revision to cure the legal flaws and defects in the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT.

15.12

Clearly then, respondents acted in bad faith and in conspiracy with one another in their futile attempt to amend and revise an anomalous and void contract by making it appear that AAA Water is part of it when in truth and in fact AAA Water did not give its conformity to the contract as shown by the fact that AAA Water is not a signatory to the said Addendum and Revision.

16.

The subject BULK WATER CONTRACT cannot be

amended and modified as the same is null and void from the beginning.

16.1

Assuming for the sake of argument that AAA Water has signed the said Addendum and Revision, still the same

42

will not ratify and render valid the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT.

16.2

Since the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT is contrary to law, morals or public policy as discussed above, then the same is an inexistent and void contract from the beginning and thus, the same cannot be ratified, amended or modified. The aforesaid Addendum and Revision cannot amend, modify and ratify the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT as the same is null and void from the beginning. Article 1409

of the Civil Code mandates that: Art. 1409. The following contracts are inexistent and void from the beginning:

1. Those whose cause, object or purpose is contrary to law, morals, good customs, public order or public policy; 2. Those which are absolutely simulated or fictitious; xxx xxx xxx 4. Those whose object is outside the commerce of men. xxx xxx xxx These contracts cannot be ratified. Neither can the right to set up the defense of illegality be waived.

16.3

Being null and void, the subject contract confers no rights nor does not impose any duty. binds nor bars any one.38 It neither

38

Caro v. CA, 158 SCRA 270

43

16.4

A void or inexistent contract is equivalent to nothing; it is absolutely wanting in civil effects.39

16.5

The action or defense for the declaration of the inexistent of a contract does not prescribe.40 Mere lapse of time cannot give effect to contracts that are null and void.41

17.

Respondent members of the Sangguniang Bayan cannot

set up the defense of good faith and presumption of regularity in the performance of duty because they have actively conspired and confederated with public respondent Guera and private respondent Gapangada to revise and amend the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT despite prior notice to them that the same is unlawful and void from the beginning:

17.1

As shown in our Affidavit-Complaint dated June 14, 2012, we have sent a letter dated April 14, 2012 42 to public respondent Guerra informing him about illegality of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT to the effect that the same is null and void for being contrary to laws, morals and public policy. On account of which, we demanded from private respondent Guerra to stop the implementation of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT.

39 40

Civil Code of the Philippines annotated by Arturo M. Tolentino, Vol. IV, Page 629, 1991 edition Article 1410, Civil Code of the Philippines 41 Civil Code of the Philippines Annotated by Edgardo M. Paras Vol IV, Page 809, 1994+ Edition. 42 Annex N" of Affidavit-Complaint dated June 14, 2012

44

17.2

We sent a letter dated April 27, 201243 to respondents members of SB advising them about the illegality of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT to the effect that it is inexistent and void from the beginning because it is contrary to laws, moral and public policy and thus, we demanded from them to pass a resolution stopping the implementation of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT. However, despite due notice and demand to stop the implementation of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT, respondent public officials made a futile attempt to revise and modify the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT so as to cure the defect of it. As mentioned above, respondent public officials made an attempt to revise and modify the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT only after they have received on June 25, 2012 a copy each of our Affidavit-Complaint dated June 14, 2012.

17.3

17.4

By their action, respondent public officials have shown their malicious intention to justify and ratify the execution of an unlawful and void contract. Stated otherwise, respondent public officials have shown that they are acting in conspiracy with one another in the execution and implementation of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT.

18.

Private Respondent IBDC Gapangada claims that IBDC

has already spent P22,655,000.00 for the subject BULK WATER

43

Annex O Affidavit-Complaint dated June 14, 2012.

45

CONTRACT as allegedly shown in "Annex 10" of his CounterAffidavit. This claim of Private respondent Gapangada is a big lie.

18.1

An examination of the said "Annex 10" will show that the same is a mere Appraiser Report prepared by Cuervo Appraisers, Inc. Worse, the said Appraiser Report is not signed and authorized by the authorized appraiser/representative Appraiser of Cuervo

Appraisers, Inc. Thus, the same is nothing but a mere scrap of paper which does not have any probative value.

19.

On the other hand, public respondent Guerra is claiming

that he coordinated with the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Center and the National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) for the preparation and execution of the subject BULK WATER

CONTRACT, so as to apparently show that the contract was executed in accordance with law. This claim of private respondent Guerra is another big lie, as shown in the Certification dated May 16, 2012 issued by the PPP Center attached to our Affidavit-Complaint as "Annex K".

19.1

The Certification dated March 16, 2012 of the PublicPrivate Partnership (PPP) Center explicitly provides that the PPP Center has no further involvement in

46

the processing of the said project. It has not participated in the preparation of bid documents, drafting of the contract and in the selection of Israel Builders and Development Corporation (IBDC) as the winning private proponent. Further, it has not received any copy of the contract with IBDC and other project-related documents.

19.2

Also, the National Economic Development Authority has issued two (2) Certifications, both dated July 11, 2012, to the effect NEDA had no prior information nor participation on the proposed Bulk Water Supply Project of the Municipality of Majayjay, Laguna. This further attests that no project contract and other documents have been submitted to this Office for review and evaluation by the proponent or project contractor. A copy of the said Certifications of NEDA are hereto attached as Annexes E and F, respectively.

20.

Public respondent SB members argue that vested rights have

already been created by the subject water contracts. Further, they argue that Article III, Section 3 of the 1987 Philippine Constitution effectuate and

47

safeguard the constitutional right of freedom to enter into a contract. These arguments are misplaced.

20.1

In the recent case of Hacienda Luisita Incorporated vs. Presidential Agrarian Reform Council,44 the Supreme Court ruled that A law authorizing interference, when appropriate, in the contractual relations between or among parties is deemed read into the contract and its implementation cannot successfully be resisted by force of the non-impairment guarantee. There is, in that instance, no impingement of the impairment clause, the non-impairment protection being applicable only to laws that derogate prior acts or contracts by enlarging, abridging or in any manner changing the intention of the parties. Impairment, in fine, obtains if a subsequent law changes the terms of a contract between the parties, imposes new conditions, dispenses with those agreed upon or withdraws existing remedies for the enforcement of the rights of the parties.45 Necessarily, the

constitutional proscription would not apply to laws already in effect at the time of contract execution, xxx.

20.2

The Supreme Court reiterated its ruling in Serrano v. Gallant Maritime Services, Inc.46:

44 45

G.R. No. 171101, July 5, 2011. Hacienda Luisita Incorporated vs. Presidential Agrarian Reform Council, G.R. No. 171101, July 5, 2011, citing BANAT Party-list v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 177508, August 7, 2009, 595 SCRA 477, 498. 46 G.R. No. 167614, March 24, 2009, 582 SCRA 254, 275-276.

48

The prohibition [against impairment of the obligation of contracts] is aligned with the general principle that laws newly enacted have only a prospective operation, and cannot affect acts or contracts already perfected; however, as to laws already in existence, their provisions are read into contracts and deemed a part thereof. Thus, the non-impairment clause under Section 10, Article II [of the Constitution] is limited in application to laws about to be enacted that would in any way derogate from existing acts or contracts by enlarging, abridging or in any manner changing the intention of the parties thereto.47

20.3

Hence, public respondent SB members cannot hide under the non-impairment clause of our Constitution as the subject water contracts were executed after the enactment of Republic Act No. 9184. And the subject water contracts are violative of existing laws and regulations.

21.

Public respondents SB members allege that they acted in good

faith and due to the honest belief that that public respondent Guera in negotiating and signing the subject water contracts with private respondent and other LGUs concerned would give paramount consideration to the interest, rights and welfare of the people of Majayjay as the Local Chief Executive of Majayjay who has the discretion and prerogative with respect to the detail, legal requisites and processes as well as the proper and legal procedures that the subject water contracts should undergo shall lacks merit.

47

Hacienda Luisita Incorporated vs. Presidential Agrarian Reform Council, G.R. No. 171101, July 5, 2011.

49

21.1

By merely relying and believing that public respondent Guera would give paramount consideration to the interest, rights and welfare of the people of Majayjay and would follow the legal requisites and procedures for the implementation of the subject water contract is

tantamount to gross negligence on the part of public respondents SB members. 21.2 By giving full authority to public respondent Guera to deal with the subject water contracts shall also be considered gross negligence on the part of public respondents SB members.

21.3

Subject to existing laws, [the Sangguniang Bayan] shall provide for the establishment, operation, maintenance, and repair of an efficient waterworks system to supply water for the inhabitants; regulate the construction, maintenance, repair and use of hydrants, pumps, cisterns and reservoirs; protect the purity and quantity of the water supply of the municipality xxx.48

21.4

The afore-cited provisions under R.A. No. 7160 would show that the allegation of public respondents SB members that the implementation of the subject water contracts is not within the domain of their powers is erroneous.

48

Republic Act No. 7160, Section 447 (4) (vii).

50

21.5

In fact, public respondents SB members have the power, duty and function to prescribe terms and conditions under which a a waterworks system shall be operated; to provide for the establishment, operation and maintenance of waterworks system; to regulate the construction, maintenance and repair and use of pumps, hydrants and reservoir; and to protect the purity and quantity of water supply in the municipality.

21.6

Accordingly, public respondent SB members cannot just give full authority to public respondent Guera to deal with the subject water contracts and by doing so, public respondent members of Sanggunian are guilty of gross misconduct and gross negligence.

21.7

In the recent cases of Ambil vs. Sandiganbayan49 and Apelado vs. People of the Philippines,50 the Supreme Court reiterated the definition of gross negligence. Gross negligence has been so defined as negligence

characterized by the want of even slight care, acting or omitting to act in a situation where there is a duty to act, not inadvertently but wilfully and intentionally with a conscious indifference to consequences in so far as other persons may be affected. It is the omission of that care

49

50

G.R. No. 175457, July 6, 2011. G.R. No. 175482, July 6, 2011.

51

which even inattentive and thoughtless men never fail to take on their own property.51

21.8

It worth stressing that public respondents and private respondent have conspired and confederated with one another to enter into and/or authorize the execution of the subject water contracts, which contracts are manifestly and grossly disadvantageous to Majayjay. According to the Supreme Court, An accepted badge of conspiracy is when the accused by their acts aimed at the same object, one performing one part of and another performing another so as to complete it with a view to the attainment of the same object, and their acts although apparently independent were in fact concerted and cooperative, indicating closeness of personal association, concerted action and concurrence of sentiments.52

22.

Public respondent Guera would like to make it appear in

his Counter-Affidavit that the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT is already accepted by the people of Majayjay when he alleged that almost 2,500 households have applied for water supply for the project. However, public respondent Guera failed to present proof of the alleged application for water system made by almost 2,500 households in Majayjay.

51 52

Sison vs. People, G.R. Nos. 170339, 170398-403, March 9, 2010, 614 SCRA 680. Ambil vs. Sandiganbayan, G.R. No. 175457 and Apelado vs. People, G.R. No. 175482, July 6, 2011, citng People v. Serrano, G.R. No. 179038, May 6, 2010, 620 SCRA 327, 336-337.

52

23.

Contrary to the claim of public respondent Guera, the

people of Majayjay were forced by respondents to apply for water connection to the supposed new water system installed by IBDC by cutting off the old water system in Majayjay over the objection of the people of Majayjay, as shown in the Affidavit dated October 18, 2012 of Mrs. Simplicia V. Rosel (Mrs. Rosel for short) hereto attached as Annex G.

24.

As stated in the said Affidavit of Mrs. Rosel, she was

forced to apply for water connection because the water supply in her house was disconnected. However, she was made to execute a water connection contract not with IBDC but with a certain company by the name of Majayjay Waters. She subsequently found out that Majayjay Waters is a fictitious company as it is not registered with the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Local Water Utilities Administration (LWUA). This shows that respondents will do anything [even to the extent of misleading the people] to be able to implement the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT.

25.

The fact that the people of Majayjay is against the subject

BULK WATER CONTRACT as well as in the intended operation by IBDC of the water system of Majayjay is shown from the fact that more than 2,000 people of Majayjay signed a manifesto asking the

53

Honorable Ombudsman to place under preventive suspension the respondent public officials as they continue to implement the subject water contract to their great prejudice and damages. A copy of the Sinumpaang Salaysay of Henry Gruezo, Roberto Urcia and Gaudencio Clado dated October 17, 2012, together with the several manifestos of more than 2,000 people of Majayjay, is hereto attached as Annex H.

26.

Unless they are placed under preventive suspension,

respondent public officials pose great threat to the lives and properties of the people of Majayjay as they have threatened and will continue to threat the people of Majayjay who will oppose the implementation of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT.

27.

As attested by Mrs. Rosel in her Affidavit dated October

18, 2012, the water connection in her house was disconnected for more than one (1) month already because she is one of the main oppositors to the execution and implementation of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT.

28.

It is only proper to place respondent pubic officials under

preventive suspension pending adjudication of this case to protect the people of Majayjay from their threat to cut off water connection to the house of any person who will oppose/object the implementation of the subject BULK WATER CONTRACT.

54

29.

As shown above, there exists strong evidence of the guilt

of respondent public officials which necessitate to place them under preventive suspension to protect the people of Majayjay from their abusive conducts which tend to put in clear and present danger the lives and properties of the people of Majayjay.

30.

It is a pure speculation for respondents to claim that this

case against them is a political harassment. Complainant Froilan Gruezo did not file a certification of candidacy to run for any elective office in Majayjay for the 2013 Election. The instant case is based upon of good legal grounds that respondents have conspired with one another to execute the three (3) Water Contract subject matter of the instant case.

31.

Contrary to respondents claim, PPP is a legitimate and

bonafide non-stock and non-profit organization with one of its mandates the promotion of good governance, transparency and accountability in government service. PPP filed the instant case to promote good governance and accountability of public officials in Majayjay so as others will not follow the unlawful conduct and/or gross misconduct committed by respondent public officials in the discharge of their duties.

32.

In causing the execution of the subject of three (3) Water

Contract in gross violation of the laws and/or and entering into a

55

manifestly and grossly disadvantageous contract to Majayjay, respondents public officials committed gross misconduct and gross negligence in the performance of their duties.

33.

The Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public

Officials and Employees enunciates the state policy to promote a high standard of ethics in public service, and enjoins public officials and employees to discharge their duties with utmost responsibility, integrity and competence. Section 4 of the Code lays down the norms of conduct which every public official and employee shall observe in the discharge and execution of their official duties, specifically providing that they shall at all times respect the rights of others, and refrain from doing acts contrary to law, good morals, good customs, public policy, public order, and public interest. Thus, any conduct contrary to these standards would qualify as conduct unbecoming of a government employee.53

34.

A long line of cases has defined misconduct as a

transgression of some established and definite rule of action, more particularly, unlawful behavior or gross negligence by the public officer.54 Jurisprudence has likewise firmly established that the misconduct is grave if it involves any of the additional elements of

53

Government Service Insurance System vs. Mayordomo, G.R. No. 191218, May 31, 2011, underscoring supplied. 54 Salvador O. Echano, Jr. v. Liberty Toledo, G.R. No. 173930, September 15, 2010, 630 SCRA 532, citing Bureau of Internal Revenue v. Organo, 468 Phil. 111, 118 (2004).

56

corruption, willful intent to violate the law or to disregard established rules, which must be proved by substantial evidence.55

35.

The respondent is reminded that the Constitution stresses

that a public office is a public trust and public officers must at all times be accountable to the people, serve them with utmost responsibility, integrity, loyalty, and efficiency, act with patriotism and justice, and lead modest lives. These constitutionally-enshrined principles, oft-repeated in our case law, are not mere rhetorical flourishes or idealistic sentiments. They should be taken as working standards by all in the public service.56

36.

This Reply-Affidavit is being executed to the attest

veracity of the foregoing statements and to prove that respondents are criminally liable for three (3) counts of violation of Section 3(g) of the R.A. 3019, as amended, otherwise known as the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act and to further prove that respondent public officials are guilty of gross misconduct and gross negligence in the performance of their duties amounting to betrayal of public trust and to also prove that there exists strong evidence of the guilt of respondent public officials to warrant their preventive suspension pending adjudication of the instant complaint.

55 56

Civil Service Commission v. Lucas, 361 Phil. 486 (1999). Id.

57

Вам также может понравиться

- Edward Jaoson P DeijoДокумент2 страницыEdward Jaoson P DeijoSulong Pinas JR100% (1)

- Reckless Imprudence Case Against Bong RunДокумент42 страницыReckless Imprudence Case Against Bong RunMau AntallanОценок пока нет

- RTC Branch 282 Drug Case Evidence ObjectionДокумент4 страницыRTC Branch 282 Drug Case Evidence ObjectionRaffy PangilinanОценок пока нет

- Answer Hanabi NewДокумент8 страницAnswer Hanabi NewJoelebie Gantonoc BarrocaОценок пока нет

- The Ark Vehicle Trading & General Merchandise Inc.: Payment ContractДокумент3 страницыThe Ark Vehicle Trading & General Merchandise Inc.: Payment ContractkeouhОценок пока нет

- Deed of Sale for Residential LotДокумент6 страницDeed of Sale for Residential LotGeraleen ValdezОценок пока нет

- Nye Verified MotionДокумент7 страницNye Verified MotionJudge Florentino FloroОценок пока нет

- Motion To Dismiss: Municipal Trial Court in CitiesДокумент3 страницыMotion To Dismiss: Municipal Trial Court in CitiesJoel C AgraОценок пока нет

- Sample SCRBD MR On Denial of Notice of Appeal EjectmentДокумент3 страницыSample SCRBD MR On Denial of Notice of Appeal EjectmentBng Gsn100% (2)

- Investigation Data FormДокумент1 страницаInvestigation Data FormCatherine Rose DiazОценок пока нет

- 10.-Complaint-Affidavit-Qualified-Theft (1) AsssДокумент2 страницы10.-Complaint-Affidavit-Qualified-Theft (1) AsssEmilio Ong SorianoОценок пока нет

- Summons: Petition, Copy of Which Is Attached, Together With The Annexes. If You Fail To AnswerДокумент1 страницаSummons: Petition, Copy of Which Is Attached, Together With The Annexes. If You Fail To AnswerRoberto Galano Jr.Оценок пока нет

- Philippines labor dispute over illegal dismissal, unpaid wagesДокумент22 страницыPhilippines labor dispute over illegal dismissal, unpaid wagesGreg RefugioОценок пока нет

- Motion to Amend Complaint in Land Dispute CaseДокумент3 страницыMotion to Amend Complaint in Land Dispute CaseRoy HirangОценок пока нет

- AnswerДокумент5 страницAnswerRossa RiveraОценок пока нет

- Counter AffidavitДокумент1 страницаCounter AffidavitLevi CorralОценок пока нет

- RTC Branch 282 issues subpoena for drug case witnessesДокумент2 страницыRTC Branch 282 issues subpoena for drug case witnessesRaffy PangilinanОценок пока нет

- Application For Probation RA 10654 (Illegal Fishing)Документ4 страницыApplication For Probation RA 10654 (Illegal Fishing)santiago wacasОценок пока нет

- Ja Expert WitnessДокумент7 страницJa Expert WitnessJan Maxine PalomataОценок пока нет

- Sworn Statement of Assets, Liabilities, and Net WorthДокумент6 страницSworn Statement of Assets, Liabilities, and Net WorthKenneth RobledoОценок пока нет

- Reply To Petition For CertiorariДокумент14 страницReply To Petition For CertiorariMarissa DacayananОценок пока нет

- Notice of Appeal SampleДокумент3 страницыNotice of Appeal SampleronaldhallidОценок пока нет

- Ombudsman Vs MedranoДокумент12 страницOmbudsman Vs MedranoAaron ViloriaОценок пока нет

- Complaintfor Damages-Esperidian Ola JRДокумент5 страницComplaintfor Damages-Esperidian Ola JRaldinОценок пока нет

- Motion For Recon - Soriano Et - Al.Документ12 страницMotion For Recon - Soriano Et - Al.Maryknoll MaltoОценок пока нет

- Complainant,: Timeliness of The MotionДокумент5 страницComplainant,: Timeliness of The MotiongiovanniОценок пока нет

- Philippine labor dispute appeal dismissal motionДокумент2 страницыPhilippine labor dispute appeal dismissal motionSanchez Roman VictorОценок пока нет

- Vdocuments - MX - Formal Offer of EvidenceДокумент3 страницыVdocuments - MX - Formal Offer of EvidenceRay LegaspiОценок пока нет

- Counter - Affidavit: MODESTO C. MAHICON, of Legal Age, Filipino Citizen and AДокумент5 страницCounter - Affidavit: MODESTO C. MAHICON, of Legal Age, Filipino Citizen and APj TignimanОценок пока нет

- LFW 2Документ35 страницLFW 2JasOn EvangelistaОценок пока нет

- MemorandumДокумент8 страницMemorandumvictor_mulz6Оценок пока нет

- Barangay Captain Charged for Misuse of Public FundsДокумент4 страницыBarangay Captain Charged for Misuse of Public FundsJuris FormaranОценок пока нет

- Child AbuseДокумент3 страницыChild AbuseHerbert Shirov Tendido SecurataОценок пока нет

- Comment (To The Memorandum of Appeal Filed by RC Victory World Trading Inc)Документ3 страницыComment (To The Memorandum of Appeal Filed by RC Victory World Trading Inc)Viktor Ivan Nicolo Tolentino MoralesОценок пока нет

- Motion To Release Cash BondДокумент2 страницыMotion To Release Cash BondJay RibsОценок пока нет

- Position Paper RecuencoДокумент8 страницPosition Paper RecuencoMarco RodmanОценок пока нет

- Motion to Quash Criminal Case for PrescriptionДокумент3 страницыMotion to Quash Criminal Case for PrescriptionedcelquibenОценок пока нет

- Motion For Issuance of Order To Compel Petitioner To Comply With The Order of The Honorable Court Dated December 22, 2o21Документ4 страницыMotion For Issuance of Order To Compel Petitioner To Comply With The Order of The Honorable Court Dated December 22, 2o21Jaime GonzalesОценок пока нет

- DOLE NLRC WithdrawalДокумент2 страницыDOLE NLRC WithdrawalchaddzkyОценок пока нет

- FINAL Counter Affidavit Maria Clara - V3Документ19 страницFINAL Counter Affidavit Maria Clara - V3Paredes Julius Leonard C.Оценок пока нет

- Motion For Issuance of InjunctionДокумент3 страницыMotion For Issuance of InjunctionMarianoFloresОценок пока нет

- Motion To Admit EstrellaДокумент2 страницыMotion To Admit EstrellaKernell Sonny SalazarОценок пока нет

- Motion to Admit Answer in Bar Discipline CaseДокумент3 страницыMotion to Admit Answer in Bar Discipline CaseKarah JaneОценок пока нет

- Morion For Reduction of Bail For TordilloДокумент1 страницаMorion For Reduction of Bail For TordilloCarolina VillenaОценок пока нет

- Accomplishment Report 2Документ2 страницыAccomplishment Report 2queen malikОценок пока нет

- Board Resolution - Meyers (NLRC Orbiter Case)Документ2 страницыBoard Resolution - Meyers (NLRC Orbiter Case)Gigi De LeonОценок пока нет

- Philippine Court Documents Object to Evidence in Drug CasesДокумент4 страницыPhilippine Court Documents Object to Evidence in Drug CasesDraei DumalantaОценок пока нет

- Affidavit of Desistance SampleДокумент2 страницыAffidavit of Desistance SampleenelehcimОценок пока нет

- Orbe Vs Lahoylahoy - Motion For ReconsiderationДокумент5 страницOrbe Vs Lahoylahoy - Motion For ReconsiderationKhalil Fedmar MarandaОценок пока нет

- Complaint-In-Intervention (1) AssssДокумент4 страницыComplaint-In-Intervention (1) AssssEmilio Ong SorianoОценок пока нет

- RTC Ruling on Appointment of Receiver for GREEN IncДокумент11 страницRTC Ruling on Appointment of Receiver for GREEN Incmisyeldv0% (1)

- Metropolitan Trial Court: Plaintiff-Appellant, Civil Case No. 10-000-90-SC - VersusДокумент2 страницыMetropolitan Trial Court: Plaintiff-Appellant, Civil Case No. 10-000-90-SC - VersusMaureen rillonОценок пока нет

- Motion For Reconsideration (MR)Документ8 страницMotion For Reconsideration (MR)JakeCarlosGarciaJr.100% (1)

- Sample Motion Fore ReconsiderationДокумент5 страницSample Motion Fore ReconsiderationMarc Joseph AguilarОценок пока нет

- Partido Marxista-Leninista NG PilipinasДокумент4 страницыPartido Marxista-Leninista NG PilipinasBien MorfeОценок пока нет

- Public Attorney'S Office Cabagan District Office: - versus-NPS Docket No. II-04-INQ-20F - 00074 For: Frustrated MurderДокумент6 страницPublic Attorney'S Office Cabagan District Office: - versus-NPS Docket No. II-04-INQ-20F - 00074 For: Frustrated MurderYNNA DERAYОценок пока нет

- Compliance - RTC - ScribdДокумент2 страницыCompliance - RTC - ScribdjakeОценок пока нет

- Sample MotEx CustodySupportДокумент3 страницыSample MotEx CustodySupportRhyz Taruc-ConsorteОценок пока нет

- Supreme Court rules on search warrantДокумент6 страницSupreme Court rules on search warrantAlicia Jane NavarroОценок пока нет

- Sabio v. SandiganbayanДокумент4 страницыSabio v. SandiganbayanabdullhОценок пока нет

- LETTER Dated April 6, 2021Документ8 страницLETTER Dated April 6, 2021Romulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- COA - 98-002 - Prohibition Against Employment by Local Government Units of Private Lawyers ToДокумент3 страницыCOA - 98-002 - Prohibition Against Employment by Local Government Units of Private Lawyers ToYan Rodriguez DasalОценок пока нет

- Letter Dated August 3, 2020 From COAДокумент1 страницаLetter Dated August 3, 2020 From COARomulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Letter Dated 4 December 2020Документ2 страницыLetter Dated 4 December 2020Romulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Position Paper (MHCI-Amando Diaz)Документ14 страницPosition Paper (MHCI-Amando Diaz)Romulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Legal Opinion No. 04 Series 2014 (Provincial Atty. of Laguna)Документ4 страницыLegal Opinion No. 04 Series 2014 (Provincial Atty. of Laguna)Romulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Decision Dated Feb. 21, 2013 (OMB Administrative Case)Документ21 страницаDecision Dated Feb. 21, 2013 (OMB Administrative Case)Romulo UrciaОценок пока нет

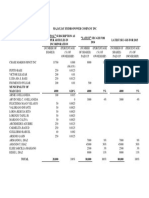

- Summary of Payments For CompensationДокумент1 страницаSummary of Payments For CompensationRomulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Letter Dated 18 December 2020Документ2 страницыLetter Dated 18 December 2020Romulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Decision Dated March 19, 2021 (MCTC Magdalena)Документ11 страницDecision Dated March 19, 2021 (MCTC Magdalena)Romulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Service of Order And-Or Sobpoena OrderДокумент5 страницService of Order And-Or Sobpoena OrderRomulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Position Paper (Mary Rose Almarinez)Документ30 страницPosition Paper (Mary Rose Almarinez)Romulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Letter Dated March 19, 2014 (Mayor Rodillas To Atty. Pat)Документ1 страницаLetter Dated March 19, 2014 (Mayor Rodillas To Atty. Pat)Romulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Counter Affidavit of RespondentsДокумент32 страницыCounter Affidavit of RespondentsRomulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Decision Dated June 17, 2016 (Mentilla Vs OMB, PPP)Документ13 страницDecision Dated June 17, 2016 (Mentilla Vs OMB, PPP)Romulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Resolution No. 116 S. 2006 With MOAДокумент11 страницResolution No. 116 S. 2006 With MOARomulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Letter Dated 29 April 2016Документ15 страницLetter Dated 29 April 2016Romulo UrciaОценок пока нет

- Decision Dated 17 June 2016 (Majayjay)Документ13 страницDecision Dated 17 June 2016 (Majayjay)Romulo UrciaОценок пока нет