Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Profit of The Cooperating Firms Is Greater Under SA Than Under Full Merger

Загружено:

Vladimir TorbicaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Profit of The Cooperating Firms Is Greater Under SA Than Under Full Merger

Загружено:

Vladimir TorbicaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

On The Choice between Strategic Alliance and Merger in the Airline Sector: The

Role of Strategic Effects

by

Philippe Barla

1

and

Christos Constantatos

2

Abstract: We consider a market with three competitors, two of which decide to

cooperate. Firms first choose capacity under demand uncertainty then compete in

quantities after the uncertainty has been resolved. We specify strategic alliance (SA)

as an agreement where two airlines jointly choose capacity and divide it among

themselves. Contrary to the full merger case, after demand is revealed the alliance

members market their capacity shares independently. Our main result is that the

profit of the cooperating firms is greater under SA than under full merger.

JEL code: L130, L240, L930

Key words: Strategic alliance, capacity, airline industry.

1

Dpartement dconomique and GREEN, Universit Laval, Qubec, Canada.

2

Corresponding author. University of Macedonia, Greece and GREEN, Universit Laval, Qubec, Canada.

Corresponding address: Egnatia Str. 156, Thessaloniki, Greece, 540 06, e-mail: cconst@uom.gr .

- 2 -

1. Introduction

In recent years, increased cooperation among airlines has been a major trend in the air

transport sector. Full mergers, code-sharing agreements and block-seat sales are

examples of the variety of cooperation forms that have been used by airlines. The need

for cooperation arises mostly from the desire of major airlines to a) offer a global service,

b) increase service quality, c) exploit size economies, and d) gain market power.

3

In this paper we admit from the outset that, for some or all of the above reasons,

airlines desire to cooperate and examine if there is an economic reason for them to prefer

forming a strategic alliance (SA) rather than to proceed with a full merger. By SA we

mean situations of partial cooperation, where firms cooperate on some decisions but act

as competitors on others. SA formation is usually attributed to i) regulations preventing

foreign airlines for providing domestic services or owning national carriers, and ii) the

fact that the investment required to develop an efficient global service network is

perhaps prohibitively large, even for major airlines.

4

While considering the above

factors as being very important, we show that strategic reasons may also enhance the

desirability of SA. Interestingly, the effect underlined in this paper could also explain the

strategy by Air France and KLM in trying to maintain some independence despite their

recent merger.

5

Lufthansa has also recently adopted such a strategy following its

acquisition of Swiss.

We consider a market with three competitors, two of which decide to cooperate.

The general structure of the model is analogous to Barla and Constantatos (2000 and

2005). Firms first choose capacity then compete in quantities. Capacity being a longer

run decision it is taken under uncertainty over the state of demand while the seat sales

decision is taken after the demand state has been revealed. In this paper, we specify SA

as an agreement where two airlines jointly choose capacity and divide it among

themselves according to some rule. Contrary to the full merger case, after demand is

3

According to Oum et al. (2000) cooperation allows i) expansion of seamless service networks (i.e., avoid

changing airline); ii) traffic feed between partners; iii) cost efficiency (economies of scale, scope and traffic

density); iv) increased service quality; v) marketing advantages (pooling of frequent flyer programs, CRS

display)

4

Oum et al. (2000).

5

This strategy has been coined one group, two airlines.

- 3 -

revealed the alliance members market their capacity shares independently. Our main

result is that the profit of the cooperating firms is greater under SA than under full

merger.

As is well known, a two-firm merger in a Cournot triopoly, while successful at

raising the price, it turns out to be detrimental for the profit of the merged firms. By

internalizing part of the effect a firms quantity decision has on rival profits, the merged

entity sets its quantity more prudently, thus yielding market share to the outside firm who

now acts more aggressively.

6

When instead of merger the cooperating firms form a SA then the above effect

disappears, since for given capacity choices the allied airlines will act as aggressively as

the outside firm. This change in attitude, while of no importance in states where the

cooperating firms are capacity constrained, becomes important in low demand states

where capacity is not binding. In those states, the SA members will market their capacity

more aggressively. This implies that in the capacity stage, the SAs reaction function is

located outwardly relative to the reaction function of the merged entity. Equilibrium

capacity of the cooperating firms is, therefore, higher under SA than under merger and

the opposite holds true for the outside rival.

While the cooperating airlines do better by forming a SA than merging, they still

make less profit compared to acting separately. The latter conclusion can be easily

reversed when joining forces allows for synergies and cost reductions.

7

If SA and merger

confer similar cost reductions, the former becomes the first best solution in terms of

profit maximization. It also dominates the merger in terms of social welfare.

The existing literature on airline strategic alliances is limited but growing. Park

(1997) and Oum, Park and Zhang (2000) analyze the effect of airline alliances on traffic

levels, fares, and welfare, distinguishing between complementary and parallel alliances.

The former refer to cases where firms link up their existing networks to build a larger

one, while the latter to collaboration between firms competing on the same routes. It is

6

See Salant et al. (1983) and Tirole (1989). While the merger succeeds to increase price, the market share

losses of the participating firms are sufficiently large to counterweight any such benefits. In strategic terms,

the merged firms adopt a soft attitude (fat cat) while competition takes place in strategic complements.

7

As a matter of fact, the cooperating firms also make less profit than their independent rival. Sufficient

cost reductions from cooperation reverse this result as well.

- 4 -

shown that complementary alliances are likely to increase welfare while parallel alliances

to decrease it.

Brueckner (2001) distinguishes two types of markets, the inter-hub and the

interline markets, where a passenger needs to use two companies in order to complete his

trip, even in the pre-alliance situation. It shows that an alliance tends to reduce (increase)

fares in the interline (inter-hub) and suggests that the positive effects of alliances may

outweigh any negative impacts.

Flores-Fillol and Moner-Collonques (2004) examines whether airlines that

employ the same hub have an incentive to create a complementary alliance. It concludes

that complementary alliances are profitable only for a sufficient degree of product

differentiation, but may nevertheless be formed as prisoners dilemma outcome even

when product differentiation is not enough. In a situation where the allied airlines and

their rival can choose whether to be the leader in a price game with product

differentiation, Lin (2004) shows that the leaders identity is parameter-dependent. Chen

and Ross (2003) studies an alliance where an incumbent accepts to provide access to its

facilities to a newcomer. It shows that, even if the alliance increases total market surplus

above the pre-alliance level, it may be socially detrimental by forestalling a more

substantial form of entry. Lin (2005) also shows that a strategic alliance may deter entry

by acting as a commitment device.

In all the above papers no comparison is made between SA and full merger.

Considering alliance as a joint venture for an intermediate product, Morash (2000) shows

how contractual terms about transfer prices and profit sharing may serve as an

appropriate commitment device yielding the alliance Stackelberg-like leadership

advantages over the outside firms. Forming a strategic alliance may therefore be superior

to full merger. Zhang and Zhang (2005) develops a two stage model of competition

between two alliances each formed by two partners linked by demand complementarities.

In the first stage, alliance partners decide on the degree of internalization by a partner of

its impact on the other partners profit. In the second stage, alliances are competing in

quantities. In this setting, internalizing demand complementarities has not only a direct

positive impact but also improves the alliance strategic position by making it tougher.

They therefore find that partners have an interest to opt for complete cooperation.

- 5 -

Section 2 presents the model, section 3 and 4 present the main results and section

5 concludes.

2. The Model

Let us have two cities A and B. The air-transport market between them (market AB) is

currently served by three airlines. Airlines 1 and 2 contemplate either forming a strategic

alliance or merging in which case the emerging company, airline M, competes against

airline 3. The SA differs from merger in that the partners join forces only in deciding the

choice of total capacity and its allocation between them. Once individual capacities are

decided, the two partners become rivals in selling AB tickets.

The three carriers are players in a three-stage game. At stage 1, firms 1 and 2

decide on the nature of their relationship: merger or SA. At stage 2, firms make their

capacity choice. Whether merger or SA, firms 1 and 2 make their capacity decisions

jointly. Stages 1 and 2 are played under demand uncertainty. At stage 3, the demand state

is revealed and firms compete in quantities, with potentially binding capacity constraints.

To keep the analysis tractable a) we assume the demand on AB to be Q P = ,

where P is price, Q is total quantity and the parameter follows a uniform distribution

on the support | | 1 , 0 ; b) we rule out any product differentiation among airlines.

13

On the cost side, we assume that the capacity costs supported in stage 2 are the

only cost element. Hence, the marginal cost associated with serving an extra passenger in

stage 3 is zero up to capacity. This is consistent with the observation that, in the airline

industry, most of the operating costs are associated with offering a seat rather than

serving a passenger.

14

Concerning the capacity cost, we introduce a very simple structure that allows us

to focus on demand and strategic considerations. We assume that: i) all airlines face

similar cost; ii) the per unit capacity cost (i.e. the cost of offering one seat) is independent

13

This is done in order to isolate the effects under study from those due to product differentiation.

14

In other words, once a seat has been added to capacity, its cost is the same whether a passenger flies on it

or not. The analysis could easily be extended to include a positive marginal cost in stage 3.

- 6 -

of the number of seats carried on a route and equal to c,

2

1

0 < c . We restrict c to values

below in order to rule out the trivial case where the market AB is never served in

equilibrium.

15

3. The Case of Merger

Airlines 1 and 2 form a single entity M that chooses total capacity as well as quantity.

The subgame examined in this section is a two-stage duopoly between symmetric

airlines, M and 3. A superscript M indicates equilibrium values in this subgame.

Lemma 1: When airlines 1 and 2 merge, ( ) 3 2 1

3

c K K

M M

M

= = , while

( )( )

2 3

3

2 4 6 1 27 1 c c

M M

M

+ = = .

Proof: Let us assume that both players have already chosen capacities with

j i

K K ,

3 , , M j i = j i . Define

i M

K 3

1

= ,

j i M

K K 2

2

+ = . There are three possibilities according

to the realization of . First, when ] , 0 (

1M

the demand is very low none of the firms

is constrained. The Cournot solution is , 3 = =

j i

q q 3 = P . Second, when

] , (

2 1 M M

(intermediate demand states) firm i is constrained while its rival is not.

The Cournot solution is

i i

K q = , ( ) 2

i j

K q = , and ( ) 2

i

K P = . Third, when ] 1 , (

2M

(high demand states) both firms are constrained with

i i

K q = ,

j j

K q = , and

j i

K K P = . Hence, at the first stage firm i maximizes

( ) ( )

i

M

i j i

M

M

i

i

M

i

cK d K K K d K

K

d E + |

.

|

\

|

+ =

1

2

2

1

1

0

2

2 9

(2)

while its rival maximizes:

( ) ( )

j

M

j j i

M

M

i

M

j

cK d K K K d

K

d E + |

.

|

\

|

+ =

1

2

2

1

2

1

0

2

2 9

. (3)

It is straightforward to show (proof available by the authors) that the only equilibrium

involves the symmetric capacity choices and profits described in the lemma, QED.

15

Obviously, if c> capacity costs in the AB exceed the maximum expected revenue from that market.

- 7 -

There is no much to comment on the merger case. Each of the merged firms 1,2,

collects half the duopoly profit. Since the two firms act in a fully coordinated manner,

the way they split capacity, hence profits, is irrelevant for the market outcome.

4. The Case of Strategic Alliance

In this section, firms 1 and 2 form a strategic alliance defined as an agreement where

partners a) jointly choose capacity in order to maximize total expected profit, b) share

this capacity equally among themselves,

16

c) market their capacity share independently.

This implies that market structure in the third stage is triopoly, potentially an asymmetric

one. A superscript A indicates equilibrium values in this subgame.

Lemma 2: When airlines 1 and 2 form a strategic alliance, unless c is too small (i.e.,

0006 . 0 > c ),

|

.

|

\

|

+ + = c c c K

A

A

2 5 . 2 2 2 2

4

1

4 1

,

|

.

|

\

|

+ + = c c c K

A

2 5 5 . 2 2 2 2

8

1

4 1

3

,

while =

A

A

( )

+ + +

4 3 2 3

5 2 2 1 2 2 3 1

24

1

c c c c c , and

=

A

3

( )

+ + + + c c c c c c 2 3 5 2 2 1 2 3 2 22 3 1

48

1

4 3 2 3

.

Proof: Since we have assumed a 50% capacity-sharing rule among alliance members,

2

2 1 A

K K K = = . We need to examine two cases according to whether

3

2K K

A

or

3

2K K

A

> . We only present the former since it turns out to be the only equilibrium.

Therefore, as increases, each alliance partner becomes capacity constrained before the

outside firm. Define

A A

K 2

1

= ,

3 2

2K K

A A

+ = , which divide the realizations of into

three zones analogous to those in the merger case. At the first stage, the alliance chooses

its capacity maximizing

17

( ) ( )

A

A

A A

A

A

A

A

A

A

cK d K K K d K

K

d E + |

.

|

\

|

+ =

1

2

3

2

1

1

0

2

2 16

2

(4)

while the outside firm maximizes

16

This division could be viewed as the result of a Nash bargaining outcome where the two airlines have

identical bargaining power.

17

Expressions (4) and (5) are analogous to expressions (2) and (3).

- 8 -

( ) ( )

3

1

2

3 3

2

1

2

1

0

2

3

2 16

cK d K K K d

K

d E

A

A

A

A

A

A

+ |

.

|

\

|

+ =

(5)

Solving the system of first order conditions and substituting optimal capacities into the

profit functions yields the expression in the lemma. Notice that 0006 . 0 c the second

order conditions for the maximization of (5) are not met, which creates a discontinuity in

the reaction function of firm 3. We simply ignore this case since it has no special

interest, QED.

With the two lemmata at hand, we proceed to show

Proposition 1: A strategic alliance is preferable to merger as a means for the

participating firms to collaborate, while the outside firm prefers that its competitors

merge; i.e., ( | 5 . 0 , 0006 . 0 c ,

M

M

A

A

and

M A

3 3

.

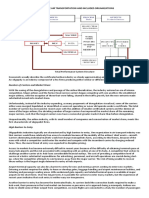

Proof: First we compute the

M

M

A

A

difference for all the admissible values of c. The

results are reported in figure 1, which shows that ( | 5 . 0 , 0006 . 0 c ,

M

M

A

A

. Similarly,

figure 2 reports the

M A

3 3

difference, which is positive ( | 5 . 0 , 0006 . 0 c , QED.

The intuition behind the results in proposition 1 is straightforward. Merging

makes the last stage reaction of the joining partners softer, thus yielding market shares to

the outside firm. To see this clearly let first

M A

K K =

12

K = , so

1 1 1

= =

A M

, and compare

profits in demand states where neither the alliance, nor the merged firm is capacity

constrained. From the first integrals in (2) and (4) it is obvious that the alliance performs

better in terms of partners profits. This happens since ] , 0 [

1

capacity choices are

irrelevant and the allied partners behave like unconstrained Cournot triopolists. We find,

therefore, the well know result of Salant, et al. (1893): when firms compete in strategic

substitutes a merger reduces the total profit of the participating firms. Hence, preferring

alliance to merger has a first strategic effect related to third stage outcome and stemming

from low demand states.

Now assume also that whether merger or alliance the outsiders capacity is fixed

at

3 3

K K = . It is easy to show that

( )

( )

( )

( )

( ) 0

2

12

4

1

3

,

12

> =

K

K K

M

K E

M

E

A

K E

A

E

. In other words,

preferring alliance to merger increases the cooperating firms marginal profit due to

- 9 -

capacity and pushes their second stage reaction function outwards. This implies that

M

M

A

A

K K > and

M A

K K

3 3

< . Figure 3 reports the

M

M

A

A

K K difference and shows that it is

positive for all the admissible values of c. This means that the alliances total capacity

exceeds that of the merged firm, therefore, whenever constrained, the alliance partners

have in total a larger market share than their merger counterpart. This holds true

independently of whether the outside firm is capacity constrained. These results also

easily explain why social welfare is always higher under the alliance than the merger (see

Figure 4).

5. Conclusion

We have shown that, in the presence of demand uncertainty airline alliance dominates

merger in terms of profits as a form of cooperation. Strategic alliance is therefore not

necessarily a second best solution justified by regulation limiting airline mergers. In the

model presented here, had the two firms remained independent they would have obtained

higher profits This is due to the fact that, in order to keep matters simple we have ruled

out any cost synergies. Obviously, by allowing for sufficient cost synergies one can find

situations where cooperating yields higher profits than remaining independent. Since the

intuition developed in this paper is unaffected by the presence of such synergies, the

superiority of alliance over merger is robust when the two forms of cooperation provide

similar cost reductions. Obviously, it remains to be verified whether a strategic alliance

allows the same type of cost synergies than a full merger.

18

In terms of policy

implications, our results suggest that, for similar cost savings, SA should be favored over

full merger by the competition authorities.

We have presented the analysis in the framework of a parallel alliance (the

collaborating airlines were supposed to initially operate on AB). Note however that the

18

Note that it is not clear that the merger necessarily performs better in that respect than the SA. Indeed,

suppose that economies of aircraft size are the main source of cost saving associated with cooperation

between airlines (i.e. the per-unit capacity cost is decreasing with the level of capacity). In this case, the

strategic advantage of the SA could very well be reinforced, since the alliance chooses more capacity than

the merged entity, and most important, it creates an asymmetry with the rival. Also, consider, for instance,

that the three airlines are somewhat differentiated, and the uncertainty that they face contains an

idiosyncratic component. If airline 1s idiosyncratic uncertainty is not perfectly correlated with that of firm

2, forming a strategic alliance allows the two airlines to reduce the cost of holding excess capacity, like in

Barla and Constantatos (2000).

- 10 -

same type of strategic effect should favor SA over merger in the case of a complementary

alliance. Indeed, suppose that airline 1 and 2 connect a third city H to cities A and B,

respectively. For some reason (e.g. regulatory constraint), they cannot serve AB directly

but if they collaborate they can offer AB passengers to fly through H. In choosing

whether to merge or to form a SA, the strategic effect identified in our analysis remains

present.

19

We can therefore conclude that, when cooperation is called for by either cost

synergies or regulatory constraints, in the presence of outside rivals SA is profit superior

to merger.

19

Obviously, airlines would also have to consider the impact of their decision on the other markets namely

AH and BH. However, since the SA makes the collaborating airlines more aggressive in terms of capacity

choice, the SA should also be superior to the merger in improving their competitive positions into these

other markets.

- 11 -

References

Barla, P. and C. Constantatos (2000), Airline Network Structure under Demand

Uncertainty. Transportation Research Part E, 36, 173-180.

Barla, P. and C. Constantatos (2005), Strategic Interactions and Airline Network

Morphology under Demand Uncertainty. European Economic Review, vol 49, 3, 703-

716.

Brueckner, J.K. (2001), The Economics of International Codesharing: An Analysis of

Airline Alliances. International Journal of Industrial Organization, vol 19, 10, 1475-

1498.

Chen, Zhiqi and T. W. Ross (2003), Cooperating upstream while competing

downstream: a theory of input joint ventures. International Journal of Industrial

Organization, 21, 381-397.

Flores-Fillol, R. and R. Moner-Collonques (2004) Strategic Effects of International

Airline Alliances Mimeo, Department of Economic Analysis, Universitat de Valncia,

Campus dels Tarongers, 46022-Valcencia, Spain.

Morash, K. (2000) Strategic Alliances as Stackelberg CartelsConcept and Equilibrium

Alliance Structure. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 18, 257-282.

Lin M.H. (2004), Strategic airline alliances and endogenous Stackelberg equilibria.

Transportation Research Part E 40, 357-384.

Lin M.H. (2005), Alliances and entry in a simple airline network. Economic Bulletin,

Vol. 12, No 2, 1-11.

- 12 -

Oum, C., J. H. Park and A. Zhang (2000), Globalization and Strategic Alliances: The

case of the Airline Industry, Pergamon.

Park, J.H. (1997), The Effect of Airline Alliances on Markets and Economic Welfare.

Transportation Research Part E, 33, 181-195.

Salant,S., S. Switzer, and R. Reynolds (1983), Losses Due To Merger: The Effects of an

Exogenous Change in Industry Structure on Cournot-Nash Equilibrium. Quarterly

Journal of Economics 48, 185-200.

Tirole, J. (1989), The Theory of Industrial Organization. MIT Press.

Zhang A. and Y. Zhang (2005), Rivalry between strategic alliances. International

Journal of Industrial Organization, forthcoming.

- 13 -

Figures

0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5

0.001

0.002

0.003

0.004

Figure 1. The

M

M

A

A

difference for all admissible values of c.

0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5

-0.015

-0.0125

-0.01

-0.0075

-0.005

-0.0025

Figure 2. The

M A

3 3

difference for all admissible values of c.

Figure 3. The

M

M

A

A

K K difference for all admissible values of c.

- 14 -

Figure 4. Difference (alliance-merger) in total surplus for all admissible values of c.

Вам также может понравиться

- Cruising to Profits, Volume 1: Transformational Strategies for Sustained Airline ProfitabilityОт EverandCruising to Profits, Volume 1: Transformational Strategies for Sustained Airline ProfitabilityОценок пока нет

- A Typology of Strategic Alliances in The Airline IndustryДокумент13 страницA Typology of Strategic Alliances in The Airline IndustrynantateaОценок пока нет

- Can Parallel Airline Alliances Be Welfare Impro - 2023 - Transportation ResearchДокумент9 страницCan Parallel Airline Alliances Be Welfare Impro - 2023 - Transportation ResearchJose Luis Moreno GomezОценок пока нет

- Paper F2nbEZhhДокумент42 страницыPaper F2nbEZhhdiamond WritersОценок пока нет

- Airline Alliance Legal WorkДокумент46 страницAirline Alliance Legal WorksidjboahОценок пока нет

- GayleBrownPaperJanuary 2015Документ40 страницGayleBrownPaperJanuary 2015lenaw7393Оценок пока нет

- Articulo Kwoka SSRN-id1275841 1Документ49 страницArticulo Kwoka SSRN-id1275841 1Fred SaundersОценок пока нет

- Vertical Integration in The Presence of Upstream CompetitionДокумент53 страницыVertical Integration in The Presence of Upstream CompetitionCore ResearchОценок пока нет

- Fontenay VerticalIntegrationPresence 2005Документ30 страницFontenay VerticalIntegrationPresence 2005Dario GFОценок пока нет

- Airline Alliances Game TheoryДокумент4 страницыAirline Alliances Game TheoryJ CОценок пока нет

- Analysis of The Enternal and External EnvirnmentДокумент4 страницыAnalysis of The Enternal and External EnvirnmentAlana BridgemohanОценок пока нет

- Download จาก..วารสารบริหารธุรกิจ: The Airline Business: Global Airline AlliancesДокумент20 страницDownload จาก..วารสารบริหารธุรกิจ: The Airline Business: Global Airline AlliancesKim Ngoc NguyenОценок пока нет

- Case 1 - Airlines IndustryДокумент6 страницCase 1 - Airlines IndustryYaswanth MaripiОценок пока нет

- IB Case StudyДокумент4 страницыIB Case StudyManisha TripathyОценок пока нет

- Wa0009.Документ29 страницWa0009.pragyanparidaОценок пока нет

- Strategic Alliances in The WДокумент11 страницStrategic Alliances in The WZorance75Оценок пока нет

- Revenue Management Games: Horizontal and Vertical CompetitionДокумент36 страницRevenue Management Games: Horizontal and Vertical CompetitionHien Heart-lovelycatОценок пока нет

- Vertical Integration in The Presence of Upstream CompetitionДокумент29 страницVertical Integration in The Presence of Upstream CompetitionCore ResearchОценок пока нет

- Organizing Vertical Boundaries: Vertical Integration and Its Alternatives Chapter ContentsДокумент14 страницOrganizing Vertical Boundaries: Vertical Integration and Its Alternatives Chapter ContentsOscar CardenasОценок пока нет

- The USA Airline Industry and Porter's Five ForcesДокумент5 страницThe USA Airline Industry and Porter's Five ForcesSena KuhuОценок пока нет

- Vertical Integration in The Presence of Upstream CompetitionДокумент59 страницVertical Integration in The Presence of Upstream CompetitionCore ResearchОценок пока нет

- 310139481TPTM5001STRATEGICALLIANCESS12011Документ12 страниц310139481TPTM5001STRATEGICALLIANCESS12011Jenny HeОценок пока нет

- Bilotkach e Huschelrath 2010Документ38 страницBilotkach e Huschelrath 2010KatiaОценок пока нет

- OECD - Measuring Market Power in MSMДокумент16 страницOECD - Measuring Market Power in MSMFitri AtikahОценок пока нет

- Case 1Документ2 страницыCase 1SheebaОценок пока нет

- Presentation On Impact Analysis of Strategic AlliancesДокумент32 страницыPresentation On Impact Analysis of Strategic Alliancesrathneshkumar100% (3)

- Southwest Airlines Business EvaluationДокумент38 страницSouthwest Airlines Business EvaluationHansen SantosoОценок пока нет

- 1997 Baird - Industrial Structure, Conduct and PerformanceДокумент16 страниц1997 Baird - Industrial Structure, Conduct and PerformanceWahyutri IndonesiaОценок пока нет

- Managerial Economic: Reading 12Документ15 страницManagerial Economic: Reading 12Mary Grace V. PeñalbaОценок пока нет

- 2015, EoT. Adler, N. and Mantin, B.Документ12 страниц2015, EoT. Adler, N. and Mantin, B.Rodrigo Freitas LopesОценок пока нет

- Strategic Alliance and Competitiveness: Theoretical FrameworkДокумент12 страницStrategic Alliance and Competitiveness: Theoretical FrameworkAbhishekОценок пока нет

- Porter'S Five Forces: Threat of New EntrantsДокумент8 страницPorter'S Five Forces: Threat of New EntrantsMostern MbilimaОценок пока нет

- Mini Case ArticleДокумент9 страницMini Case Articlepaulxu94Оценок пока нет

- Dartmouth Shankar Vergho Aff 6 NDT FinalsДокумент90 страницDartmouth Shankar Vergho Aff 6 NDT Finalsjohn kОценок пока нет

- SSRN Id3280688Документ47 страницSSRN Id3280688Andres Felipe Leguizamon LopezОценок пока нет

- Chapter 9 Case StudyДокумент2 страницыChapter 9 Case StudyJemima LopezОценок пока нет

- An Analysis of Delta Air Lines - Based OnДокумент5 страницAn Analysis of Delta Air Lines - Based OnYan FengОценок пока нет

- Assignment 2 - Innovation ManagementДокумент15 страницAssignment 2 - Innovation ManagementClive Mdklm40% (5)

- Porter's 5 Forces and IMCДокумент4 страницыPorter's 5 Forces and IMCVanshika ChopraОценок пока нет

- Alianzas InternacionalesДокумент17 страницAlianzas InternacionalesSara Barranco LegranОценок пока нет

- Strategic Alliances in The Aviation Industry: An Analysis of Turkish Airlines ExperienceДокумент8 страницStrategic Alliances in The Aviation Industry: An Analysis of Turkish Airlines Experienceasdas asfasfasdОценок пока нет

- Airline Capital Structure: One Parameter in TheДокумент26 страницAirline Capital Structure: One Parameter in Thedavidmarganti100% (1)

- Alliance Formation, Both Globally and Locally, Chapter 9Документ6 страницAlliance Formation, Both Globally and Locally, Chapter 9Jeralden Namoc BalaguaОценок пока нет

- Modeling Applications in The Airline Industry Ch1Документ17 страницModeling Applications in The Airline Industry Ch1Abhinav GiriОценок пока нет

- Economic Characteristics of The Air Transportation and Included OrganizationsДокумент4 страницыEconomic Characteristics of The Air Transportation and Included OrganizationsVence Dela Tonga PortesОценок пока нет

- Paper B5f8ArtfДокумент42 страницыPaper B5f8ArtfRona DesabilleОценок пока нет

- The Key Success FactorsДокумент16 страницThe Key Success Factorslavender_soul0% (1)

- 5219-Article Text-14479-1-10-20190129Документ21 страница5219-Article Text-14479-1-10-20190129rОценок пока нет

- Transportation Research Part A: Sylvain Bourjade, Regis Huc, Catherine Muller-VibesДокумент17 страницTransportation Research Part A: Sylvain Bourjade, Regis Huc, Catherine Muller-VibeslesliekjОценок пока нет

- Airline Strategy From Network ManagementДокумент34 страницыAirline Strategy From Network ManagementSantanu DasОценок пока нет

- Porter's Five Forces: Threat of New EntrantsДокумент6 страницPorter's Five Forces: Threat of New EntrantschocolatelymilkОценок пока нет

- Observations and Future ResearchДокумент3 страницыObservations and Future ResearchPetronela IstrateОценок пока нет

- University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB) : Course Title: Strategic Management Course Code: BUS 307 Section: 03Документ23 страницыUniversity of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB) : Course Title: Strategic Management Course Code: BUS 307 Section: 03Dhiraj Chandro RayОценок пока нет

- Analysis of Strategic Alliance As A Source of Competitive Ad PDFДокумент86 страницAnalysis of Strategic Alliance As A Source of Competitive Ad PDFMariam MassaȜdehОценок пока нет

- Master Thesis Airline IndustryДокумент4 страницыMaster Thesis Airline Industryerinperezphoenix100% (2)

- 1 s2.0 0167718786900275 MainДокумент13 страниц1 s2.0 0167718786900275 MainseanflippedОценок пока нет

- Mini Case Chapter 9Документ4 страницыMini Case Chapter 9Angelina AliciaОценок пока нет

- Problem Sets For Micro BookДокумент98 страницProblem Sets For Micro BookNgoc Chi MinhОценок пока нет

- Managerial Economics and Strategy: Third EditionДокумент41 страницаManagerial Economics and Strategy: Third EditionRaeОценок пока нет

- Advanced MicroeconomicsДокумент13 страницAdvanced Microeconomicsthe1uploaderОценок пока нет

- Advanced Microeconomics Theory I Question 123456 M SДокумент36 страницAdvanced Microeconomics Theory I Question 123456 M SJeannette EcholsОценок пока нет

- 2008 Final Exam - .AnswersДокумент17 страниц2008 Final Exam - .Answersd00m_0daydumpОценок пока нет

- The Cola WarsДокумент38 страницThe Cola Warssonulal83% (6)

- Notes Unconstrained Max PDFДокумент10 страницNotes Unconstrained Max PDFDeepak SanjelОценок пока нет

- Econ 161 - Exercise Set 2Документ3 страницыEcon 161 - Exercise Set 2SofiaОценок пока нет

- Gibbons Solution Problem Set 1.5 1.7 & 1. 8Документ8 страницGibbons Solution Problem Set 1.5 1.7 & 1. 8senopee100% (2)

- Monopolistic and Oligopoly Competition PDFДокумент28 страницMonopolistic and Oligopoly Competition PDFJennifer CarliseОценок пока нет

- ECO206Y5 Final 2012W CarolynPitchikДокумент7 страницECO206Y5 Final 2012W CarolynPitchikexamkillerОценок пока нет

- Oligopoly Market StructureДокумент31 страницаOligopoly Market StructureMulugeta tequarОценок пока нет

- Cournot OligopolyДокумент5 страницCournot OligopolyTanya YugalОценок пока нет

- CH 05Документ13 страницCH 05Reem AdОценок пока нет

- Game Theory 2Документ15 страницGame Theory 2ABHIJITH A AОценок пока нет

- Chapter 12Документ100 страницChapter 12cutiee cookieyОценок пока нет

- University College London: Examination For Internal StudentsДокумент4 страницыUniversity College London: Examination For Internal StudentsKarolina KaczmarekОценок пока нет

- Mec 001Документ6 страницMec 001Tamash MajumdarОценок пока нет

- KUL Advanced Microeconomics 2019 Problem Set 1Документ4 страницыKUL Advanced Microeconomics 2019 Problem Set 1Fedor DostОценок пока нет

- EC3099 - Industrial Economics - 2003 Examiners Commentaries - Zone-AДокумент6 страницEC3099 - Industrial Economics - 2003 Examiners Commentaries - Zone-AAishwarya PotdarОценок пока нет

- ID: - Name: - Microeconomics Spring 2020, NCKU, Dept. of Econ Recitation 10Документ4 страницыID: - Name: - Microeconomics Spring 2020, NCKU, Dept. of Econ Recitation 10bibby88888888Оценок пока нет

- 04.oligopoly SolutionsДокумент3 страницы04.oligopoly SolutionsfedericodtОценок пока нет

- Io Presentation On BhevioralДокумент17 страницIo Presentation On Bhevioralvlabrague6426Оценок пока нет

- Introduction To Economic Analysis - Econ 1005Y Tutorial 2Документ5 страницIntroduction To Economic Analysis - Econ 1005Y Tutorial 280tekОценок пока нет

- Game Theory & Asymmetric InformationДокумент88 страницGame Theory & Asymmetric InformationSamiur RahmanОценок пока нет

- Competition in Electricity Markets With Renewable Energy SourcesДокумент20 страницCompetition in Electricity Markets With Renewable Energy SourcesNirob MahmudОценок пока нет

- Microeconomics Competition and Market Structure OligopolyДокумент17 страницMicroeconomics Competition and Market Structure Oligopolymuhammadyasirmpae4Оценок пока нет

- Io-Exercises ImportantДокумент33 страницыIo-Exercises ImportantjayaniОценок пока нет

- Mi 2 CHAPTER 2Документ16 страницMi 2 CHAPTER 2Kifu YeОценок пока нет

- Literature Review MonopolyДокумент8 страницLiterature Review Monopolyafduaciuf100% (1)