Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Blu Review I. Mayorga

Загружено:

Virginia GriseАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Blu Review I. Mayorga

Загружено:

Virginia GriseАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Access Provided by The University Of Texas at Austin, General Libraries at 11/14/12 11:11PM GMT

412

/ Theatre Journal

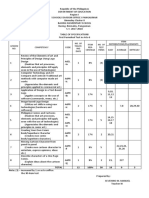

ries Award, Virginia Grises blu is a deeply political play that focuses on the ramifications of such harrowing figures, especially for youth, by dramatizing two generations of a Mexican American family within a fictionalized Barrio U.S.A. blus title not only eponymously names the familys eldest teenage son (played by Xavi Moreno), whose birth, life, and death (while serving as a soldier in Iraq) the play tracks, but it also announces the centrality of spiritual despair in its characters lives. Working through the dramaturgical schema of a fragmented memory play and relying on ensemble storytelling, blu is an absorbing mediation of memories, dreams, rituals, and prayers that illustrates the interplay between macro-level sociopolitical conditions in the barrio and micro-level adaptations by its Latina/o residents. Director Laurie Carloss staging placed emphasis on the plays lean, poetically metered language and its ensemble-storytelling styleits most arresting element. To this end, CoAs intimate black-box theatre held a bare minimum of set pieces to suggest blus barrio: a sacred tree, a column tagged with graffiti, a prison cell occupied by the familys father Eme (pronounced m-, also the name of one of the most notorious prison gangs in the California penal system) (Luis Galindo), a tiny house tumbled onto its side to signify the familys home, and a separate pitched-roof unit (sans house) set on the stage floor that served as a liminal space between street and sky where blus younger sister Gemini (Alexandra Jimenez) perched during much of the play in order to better scan the stars or search the horizon. The sets stark, open quality thoughtfully upended overdetermined gritty representations of the barrio, and instead offered a surrealistic landscape that lent itself to the plays central motif of dreaming, positioned as an act of resistance against the barrios tribulations. blu often made use of plural-vocal dialogic exchanges among characters, an ensemble-based narrative technique that heightened the plays theatricality and positioned it firmly away from realism, as characters spoke across time and among different spaces to describe their circumstances. In performance, these plural-vocal exchanges delivered a poetically charged choral effect that evocatively distributed the narrative task of storytelling among different sets of characters. For example, when blu and his younger brother Lunatico (Phillip Garcia) recounted the violent initiation rite of being jumped into a gang, they began with a shared account that quickly cut back and forth between them. Then Eme joined his sons by adding his memory of gang initiation to their visceral reenactment. Shared narration of this kind allowed the play to trace out the

utes. Early Plays, less interested in the bodies of the actors per se, accomplished this visceral audience response through song. From the spectral voices that began Moon of the Caribees to the multiple songs both scripted and not, it was when the actors were singing that their bodies reminded us of our own. Watching the actors labor in the process of singing was perhaps the only time we really saw them utilize their whole bodies onstage, evoking a bodily awareness all the more striking for its absence during the majority of the production. Throughout The Complete & Condensed the mixtures of body and object were permeable for both audience and performers. Conversely, Early Plays worked to tear apart the excessive materiality that ONeill wrote into his texts by separating the bodies of the actors from the words they spoke and the immaterial props that accompanied them. Both productions actively worked against ONeills canonical texts, stripping the playwright of both spoken and unspoken words and replacing them with material and immaterial props that paradoxically subverted and fulfilled the plays. By creatively reimagining ONeills words, these two shows also proved that the somewhat imposing stage directions and dialect of the plays are not obstacles, but rather sites for potentiality. In this way, both groups proved that ONeills works can have an active life outside of the realm of realism and naturalism.

BESS ROWEN The Graduate Center/CUNY

BLU. By Virginia Grise. Directed by Laurie Carlos. La Colectiva Chorizo y Maguey, with Company of Angels, Los Angeles. 30 October 2011.

In his program note, Company of Angels (CoA) artistic director Armando Molina explained how the world premiere of a Chicana-authored, awardwinning play like blu precisely suited CoA and its mission to produce theatre that portrays the 80 percent of Los Angeles residents who rarely see themselves represented onstage. He reminded his audience that the underrepresented Latina/o world of blu theatrically adumbrates barrios like Boyle Heights, the 98 percent Latina/o-populated neighborhood located just across the river from CoAs downtown Los Angeles location. Boyle Heights has a 60 percent high school dropout rate, along with a median annual income of $24,000disturbing statistics that also describe barrios throughout the United States. Garnering the 2010 Yale Drama Se-

PERFORMANCE REVIEWS

413

Diana de la Cruz, Romi Dias, and Alexandra Jimenez in blu. (Photo: Graham Kolbeins.) pervasiveness of violence across two generations of men, and among three perspectives. Carloss staging enhanced blus plural-vocal narrative structure with nonnaturalistic, highly physical movement in effect, powerful dances among characters that drew from expressionistic movement vocabularies, as well as sources like hip-hop. In scenes between father and sons, for example, this stylized physicality effectively upbraided the shopworn gestures of Latino male bravado and gangbangers with fresh grammars of masculine physicality and homosocial intimacy and proved to be some of Carloss most luminous staging. While Eme, blu, and Lunatico collectively showed particular social forces in the barrio, including gang life, police harassment, abasement in public schools, and the prison system, the familys women juxtaposed these events with articulations of teen pregnancy, single motherhood, and domestic abuse. After Emes gang activities led to his imprisonment, the familys mother Soledad (Romi Dias) began a relationship with Hailstorm (Diana de la Cruz), a two-spirit Xicana-Indgena woman. Their relationship offered a vision of love and family-making that foregrounded the catalytic potential of queerness. Carlos countered the male characters kinetic group scenes by staging Hailstorm and Soledads romantic intersections in intimate, ritualistic tones, where their social critiques were often infused with sensuality. Ritualistic tones blended with storytelling also carried through to scenes among Hailstorm, Soledad, and Gemini as well, most especially when Hailstorm introduced mother and daughter to the redressive figure of Coyolxauhquithe Aztec goddess slain by her war-god brother, whose head becomes the moona female figure who, like Soledad and Gemini, sought to quell war and violence in her family. Indigenous articulations like these

Luis Galindo, Xavi Moreno, and Phillip Garcia in blu. (Photo: Graham Kolbeins.) among the women were imbued with ceremonial movement, music, and reverence that often came to entail the entire ensemble in shared enactments that conjured a sense of sacred ritual, even as they reminded the audience of Chicana/os Native origins. In this, Mexican Indian mythology not only highlighted the legacy of colonialism within the barrios contemporary dilemmas, but also served as a force of cultural grounding and efficacy for the women. When blus sociocultural critiques extricated Chicana/os Native origins, I could not help but feel strong resonances between blu and Cherre Moragas The Hungry Woman: A Mexican Medea, which also animates the potentiality of both queerness and Chicana/o indigeneity. If blu attended to the interlocking social forces that dead-end young peoples lives in the barrio, then blus decision to join the military afforded its most searing example. In the plays dissembled chronology, its story had already revealed blus death; therefore the plays ending concentrated on its transpiration and implications. Hailstorm delivered one of blus strongest anti-war indictments by correlating military service to the barrios schematics: blu was merely switching out one gang for another. In a highly affecting recounting, Gemini and Eme jointly narrated how while flying in a helicopter in Iraqfinally free from the barrios constraintsblu was shot out of the sky. Here, the play clearly suggested that while military life held the tantalizing promises of purpose, pay, and escape for blu, in a time of war, promises of this kind are often made in exchange for young Latina/os lives. In response, Gemini used her grief to fashion a transformation, because blus death signaled an opportunity for Coyolxauhquis myth to be rewrittenbrother did not kill sister, as the myth foretold. She vowed to resurrect the deitys feminist energies; violence would not determine her life.

414

/ Theatre Journal

Somewhere, which takes its title from West Side Storyspecifically, Tony and Marias iconic song about the hope for a place for usis a dramatic homage to the Golden Age of Broadway. Each of the four central characters is immersed so much in the culture of Broadway that it has become constitutive to their sense of self and one another. The 20-year-old Alejandro first worked on Broadway as a child in the King and I, although he has given up performing, despite his mothers protests, in order to help with the familys expenses; Francisco, his 21-year-old brother, while less successful as an actor, carries the optimism, enthusiasm, and ambition that his younger sibling has lost; their mother, herself a cabaret singer, behaves as if Chita, Ethel, and Jerome are all familial intimates; and Rebecca, an aspiring dancer and the youngest at age 17, hopes to be cast in the upcoming film version of West Side Story, which seems likely given that the brothers best friend, Jamie, is Jerome Robbinss assistant. The production at the Old Globe maximized the versatility of the actorsessential to Matthew Lopezs dramaturgical showcase of a family of artistsby incorporating music, performance, and especially dance (beautifully choreographed by Greg Graham) throughout the show. We saw the brothers rehearsing their acting scenes; the sister dancing solo as Maria in West Side Story as she set the table for the family dinner; and the two boyhood friends, Alejandro and Jamie, attempting to recreate the specific choreography of an old sequence in an extended dance scene, which nearly stole the show. In Somewhere, someone is always performing! The Candelarias are their own best variety show, and their own best audience too. Despite the familys boisterous pleasure in all things Broadway, the Candelarias face several challenging dilemmas that need immediate attention. Their buildingin truth most of, if not their entire, neighborhoodis being razed to make room for Robert Mosess Lincoln Center. The play addresses the complicated politics of urban renewal and ethnic belonging, as most of the inhabitants evacuated to a housing project in Brooklyn are Puerto Rican. Matthew Lopezs subtle yet persuasive perspective asked us to consider what is lost and gained in the name of cultural progress. The play is ambitious; it is difficult, for example, to contain the play within a limited plot line. Is it about the bonds of kinship? The role of the arts? Urban gentrification? Matthew Lopezs sophisticated dramaturgy allows his play the space to be all these things and more. While many of the local critics faulted the play for this matter, hoping for a more focused narrative, I found the plays messiness exciting and in sync with the melodramatic and totally entertaining family situational comedy that it

blu closed with a striking, final plural-vocal ceremonial exchange by the ensemble, a threnody that transfigured the affective denotations of blue from dispiritedness to hope, as the family asked the life-giving blue of the ocean, sky, horizon, and their son/brother to carry us home. Considering the plays resolute effort to index young Latina/o lives, it came as no surprise that a decidedly young, majority Latina/o and people-of-color constituency had populated the evenings audience. Leaving the theatre, the palpably provoked spectators spilled into an LA night sky filled with the whirring blades of police helicopters and the faint glimmer of stars overhead, many returning themselves to their homes across the river in Barrio U.S.A.

IRMA MAYORGA Dartmouth College

SOMEWHERE. Written by Matthew Lopez. Directed by Giovanna Sardelli. The Old Globe, San Diego, California. 5 October 2011.

In the opening scene of Matthew Lopezs excellent new play Somewhere, two brothers, Francisco and Alejandro, are battling it out in the living room of their Manhattan tenement. It is the summer of 1959 and the brothers, young Puerto Ricans, are supposed to be packing the familys belongings before the bulldozers arrive to demolish the building later that week. The play begins in the midst of this escalating heated exchange and violence seems immanent. The palpable machismo of the moment is brilliantly and abruptly ruptured when we learn that they are not actually fighting each other, but rehearsing a scene from Elia Kazans On the Waterfront for Franciscos acting class. The Candelaria brothers, it turns out, are deeply entrenched in the performing arts; the play showcases their investments in film, theatre, and dance in ways that underline the role of the arts in their lives. Consider that the brothers are interrupted only when their mother, Inez, and younger sister, Rebecca, return from their jobs ushering at West Side Story at the Winter Garden, raving about Chita Riveras performance before arguing with the boys about the merits of Leonard Bernsteins music for On the Waterfront and West Side Story. This familys argot is that of musical theatre and popular culture. The fact that Inez, a Latina Mama Rose, was played by Tony Awardwinning Broadway veteran Priscilla Lopez (A Chorus Line, A Night in the Ukraine, Anna in the Tropics, In the Heights), only added to the delight that the play consistently delivered as the production unfolded.

Вам также может понравиться

- Mimetic Disillusion: Eugene O'Neill, Tennessee Williams, and U.S. Dramatic RealismОт EverandMimetic Disillusion: Eugene O'Neill, Tennessee Williams, and U.S. Dramatic RealismОценок пока нет

- JADT Vol19 n1 Winter2007 Lee Having Favorini BarriosДокумент100 страницJADT Vol19 n1 Winter2007 Lee Having Favorini BarriossegalcenterОценок пока нет

- An Other Othello Djanet SearsДокумент15 страницAn Other Othello Djanet SearsSana Gayed100% (1)

- The Latina/o Theatre Commons 2013 National Convening: A Narrative ReportОт EverandThe Latina/o Theatre Commons 2013 National Convening: A Narrative ReportОценок пока нет

- Mixed Faith and Shared Feeling: Theater in Post-Reformation LondonОт EverandMixed Faith and Shared Feeling: Theater in Post-Reformation LondonОценок пока нет

- The Transition of Doodle Pequeno CastlistДокумент1 страницаThe Transition of Doodle Pequeno Castlistapi-238209038Оценок пока нет

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Maria Irene Fornés and Multispatial TheaterОт EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Maria Irene Fornés and Multispatial TheaterОценок пока нет

- The Life and Genius of Anton Chekhov: Letters, Diary, Reminiscences and Biography: Assorted Collection of Autobiographical Writings of the Renowned Russian Author and Playwright of Uncle Vanya, The Cherry Orchard, The Three Sisters and The SeagullОт EverandThe Life and Genius of Anton Chekhov: Letters, Diary, Reminiscences and Biography: Assorted Collection of Autobiographical Writings of the Renowned Russian Author and Playwright of Uncle Vanya, The Cherry Orchard, The Three Sisters and The SeagullОценок пока нет

- Imagining Medea: Rhodessa Jones and Theater for Incarcerated WomenОт EverandImagining Medea: Rhodessa Jones and Theater for Incarcerated WomenОценок пока нет

- What a Piece of Work Is Man!: Full-Length Plays for Leading WomenОт EverandWhat a Piece of Work Is Man!: Full-Length Plays for Leading WomenОценок пока нет

- Bigotry on Broadway: An Anthology Edited by Ishmael Reed and Carla BlankОт EverandBigotry on Broadway: An Anthology Edited by Ishmael Reed and Carla BlankОценок пока нет

- Chile Con Carne and Other Early Works: Chile Con Carne, ¿QUE PASA with LA RAZA, eh?, and In a Land Called I Don’t RememberОт EverandChile Con Carne and Other Early Works: Chile Con Carne, ¿QUE PASA with LA RAZA, eh?, and In a Land Called I Don’t RememberРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Theatre Symposium, Vol. 23: Theatre and YouthОт EverandTheatre Symposium, Vol. 23: Theatre and YouthDavid S. ThompsonОценок пока нет

- The Flower of Beauty: Two Commedia dell'Arte Plays for the Modern StageОт EverandThe Flower of Beauty: Two Commedia dell'Arte Plays for the Modern StageОценок пока нет

- Howard Barker's art of theatre: Essays on his plays, poetry and production workОт EverandHoward Barker's art of theatre: Essays on his plays, poetry and production workОценок пока нет

- Aecom Holiday List-2017: Staff Working On Site Offices Would Follow Their Respective Client Holiday ListДокумент1 страницаAecom Holiday List-2017: Staff Working On Site Offices Would Follow Their Respective Client Holiday ListAntony John VianyОценок пока нет

- Mysore Travel GuideДокумент18 страницMysore Travel GuideNipun SahniОценок пока нет

- How The World Was Created (Panayan)Документ25 страницHow The World Was Created (Panayan)Mary Kris De AsisОценок пока нет

- Great Drawings and Illustrations From Punch 1841-1901Документ166 страницGreat Drawings and Illustrations From Punch 1841-1901torosross6062100% (3)

- Brand Personality of KHAADIДокумент17 страницBrand Personality of KHAADIBusteD WorlDОценок пока нет

- Transitional Words and PhrasesДокумент3 страницыTransitional Words and PhrasesEricDenby89% (9)

- The BellДокумент1 страницаThe BellDiyonata KortezОценок пока нет

- DorksДокумент170 страницDorksjemmmОценок пока нет

- Transition Elements Final 1Документ44 страницыTransition Elements Final 1Venkatesh MishraОценок пока нет

- Shakespeare EssayДокумент4 страницыShakespeare EssayAdy CookОценок пока нет

- Freestyle AcrobaticsДокумент2 страницыFreestyle AcrobaticsAnaLiaОценок пока нет

- Nomenclature: Hibiscus Is A Genus of Flowering Plants in The Mallow Family, Malvaceae. The Genus IsДокумент4 страницыNomenclature: Hibiscus Is A Genus of Flowering Plants in The Mallow Family, Malvaceae. The Genus IsKarl Chan UyОценок пока нет

- Análisis de PoemasДокумент6 страницAnálisis de PoemasSTEFANY MARGARITA MEZA MERIÑOОценок пока нет

- BOOK The 7 Prayers Jesus Gave To Saint Bridget of SwedenДокумент7 страницBOOK The 7 Prayers Jesus Gave To Saint Bridget of SwedenSandra Gualdron0% (1)

- Cendrillon 17-18 Guide PDFДокумент41 страницаCendrillon 17-18 Guide PDFKenneth PlasaОценок пока нет

- Development of Cinema in The Philippines-1Документ25 страницDevelopment of Cinema in The Philippines-1Ryan MartinezОценок пока нет

- FREE Music Lessons From Berklee College of Music: A Modern Method For GuitarДокумент4 страницыFREE Music Lessons From Berklee College of Music: A Modern Method For Guitarbgiangre8372Оценок пока нет

- Mol Serge Classical Fighting Arts of Japan PDFДокумент251 страницаMol Serge Classical Fighting Arts of Japan PDFMark ZlomislicОценок пока нет

- 6th Grade Writing PromptsДокумент4 страницы6th Grade Writing Promptssuzanne_ongkowОценок пока нет

- Evelyn Waugh Elena PDFДокумент2 страницыEvelyn Waugh Elena PDFElizabeth0% (1)

- Elements of Design ActivityДокумент4 страницыElements of Design ActivityMegan Roxanne PiperОценок пока нет

- Perfect Espresso:: The First Step To Make AДокумент3 страницыPerfect Espresso:: The First Step To Make AAlyHDОценок пока нет

- Make The Sign of The Cross: St. Faustina's Prayer For SinnersДокумент4 страницыMake The Sign of The Cross: St. Faustina's Prayer For SinnersFelix JosephОценок пока нет

- The First Religion of MankindДокумент23 страницыThe First Religion of MankindaxelaltОценок пока нет

- Fun HomeДокумент242 страницыFun HomeMario Alexis González93% (40)

- MK Foundations of Multidimensional and Metric Data Structures 0123694469 PDFДокумент1 022 страницыMK Foundations of Multidimensional and Metric Data Structures 0123694469 PDFnazibОценок пока нет

- Asme section-IIДокумент25 страницAsme section-IIAmit Singh100% (10)

- First Periodical Test in Arts.6Документ6 страницFirst Periodical Test in Arts.6Cathlyn Joy GanadenОценок пока нет

- NCERT Notes - Vedic Civilization - Important Events (Ancient Indian History Notes For UPSC)Документ1 страницаNCERT Notes - Vedic Civilization - Important Events (Ancient Indian History Notes For UPSC)rajat tanwarОценок пока нет