Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Barriers To Implementing Flexible Transport Services An International Comparison of

Загружено:

YinGz ZaИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Barriers To Implementing Flexible Transport Services An International Comparison of

Загружено:

YinGz ZaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Research in Transportation Business & Management 3 (2012) 311

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Research in Transportation Business & Management

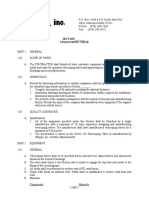

Barriers to implementing exible transport services: An international comparison of the experiences in Australia, Europe and USA

Corinne Mulley a,, John Nelson b, Roger Teal c, Steve Wright b, Rhonda Daniels d

a

Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies, The University of Sydney, Australia Centre for Transport Research, University of Aberdeen, UK DemandTrans Solutions, Inc. USA d 2a Glenelg St, Sutherland NSW 2232, Australia

b c

a r t i c l e

i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Flexible transport services (FTS) are an emerging term in passenger transport which covers a range of mobility offers where services are exible in one or more of the dimensions of route, vehicle allocation, vehicle operator, type of payment and passenger category. Research in New South Wales (NSW), Australia identied a number of barriers to the implementation of FTS and this paper explores the extent to which these barriers have been encountered and tackled in the USA and Europe where exible transport services have been used increasingly as part of the public transport mix in areas where demand is too low to support conventional public transport. Barriers include institutional frameworks such as policy and regulation; economic issues of funding and fares; operational issues of eet and vehicles; as well as operator and community attitudes; and information and education. The paper makes recommendations to enable and encourage greater use of exible transport services by transport service planners and providers through the sharing of best practice and information on overcoming barriers to implementation. 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Article history: Received 30 November 2011 Received in revised form 13 April 2012 Accepted 13 April 2012 Available online 12 May 2012 Keywords: International experience Flexible transport services Barriers to implementation

1. Introduction Flexible transport services (FTS) are broadly dened as a transport service where at least one of the characteristics (route, vehicle, schedule, passenger and payment system) is not xed. In the public transport context, this contrasts with the service which has a xed route, xed timetable and fare, and vehicles with drivers scheduled on a regular basis. FTS have a number of different markets. They can be used as access services in areas where resources are concentrated on strategic or trunk corridors or where topographical constraints (such as peninsulas and isolated valleys) make conventional public transport services difcult to provide. FTS are particularly suited to being the principal public transport offer to areas of low demand such as on the fringes of urban areas where there is dispersed development or in the new residential areas on greeneld sites where population may not initially justify conventional services. FTS are increasingly used to provide services at times of the day or weekend when conventional services achieve low levels of patronage typically late evening and weekend services and in many cases they have been enhanced by the appropriate application of transport telematics. The motivation of this paper is to draw lessons from the implementation of FTS in different spatial settings so as to understand why FTS occur in some places and countries and not in others. Thus,

Corresponding author. Tel.: + 61 293 510 103. E-mail address: corinne.mulley@sydney.edu.au (C. Mulley). 2210-5395/$ see front matter 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.rtbm.2012.04.001

the main focus of this paper is to identify the variety of barriers which exist to prevent more widespread implementation of exible transport services. Research in New South Wales (NSW), Australia (Daniels & Mulley, 2012) identied a number of barriers to the implementation of FTS, many of which seem to have been an issue for some time, as discussed in Enoch, Potter, Parkhurst, and Smith (2004) and SAMPO (1997). This paper therefore explores the extent to which these barriers have been encountered and tackled in the USA and Europe. The categorisation of the barriers follows Daniels and Mulley (2012). This identies some barriers arising from institutional: policy, legislative, or regulatory arrangements which work against development and implementation of FTS. Other barriers are economic in nature, whether due to funding constraints or the inherently higher costs per exible service trip. There are also operational factors that may impede FTS, such as the availability of appropriate vehicles or standard operational practices (such as simplistic eet conguration structures) that generate higher costs than necessary. FTS implementation does not occur in an organisational vacuum, and long standing public transport industry attitudes, perceptions and cultural conditioning have frequently been cited as an impediment to new forms of service. Finally, as an innovative service concept, the adoption of FTS may be obstructed by informational deciencies that prevent the relevant actors (including passengers) from fully understanding the realistic potentials of these types of services. The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of experience with open access FTS drawing primarily on examples from

C. Mulley et al. / Research in Transportation Business & Management 3 (2012) 311

Australia, Europe and USA. In Section 2.1 ve sets of barriers, encompassing institutional frameworks; economic issues; operational issues; operator and community attitudes; and nally information and education, are analysed with respect to experience from Australia, Europe and USA. Finally, implications for managerial practice are identied by considering the conclusions derived from the study of each of the sets of barriers. 2. Development of exible transport services around the world FTS cover a wide range of mobility offer concepts, although currently Demand Responsive Transport (DRT) is arguably best known. DRT has been dened as any form of transport where day to day service provision is inuenced by the demands of users (Derek Halden Consultancy (DHC), 2006). DRT is associated with public transport services operated by smaller vehicles (small buses, minibuses) and maxi-taxis (large taxis, often seating up to 10 passengers, depending on the jurisdiction) and while the denition of FTS encompasses DRT it has a wider and more generic denition. FTS is dened as including a range of passenger transport mobility offers, where services are exible in one or more of the dimensions of route, vehicle allocation, vehicle operator, type of payment and passenger category. It is therefore a exible, integrated and customer centric adaptive transport option that sits somewhere between private car ownership and xed route traditional transit (Waters, cited in Ferreira, Charles, & Tether, 2007). FTS can be either for general public use, or can be for closed user groups such as special services for people with disabilities and the elderly. In this paper, the focus is on the provision of services for the general public which includes people with disabilities and the elderly where appropriate services are provided. A recent study of such an open access FTS service is reported in Nelson and Phonphitakchai (2012). FTS have been introduced both as part of the public transport mix and also to meet certain accessibility gaps. Accessibility is a multidimensional concept relating to the ease with which individuals can reach destinations. A number of different accessibility gaps can therefore exist ranging from a lack of service (spatial gap), inaccessible vehicles (physical gap), no service at the required time or the journey takes too long (time gap), passengers do not have the required information (information gap), services are too expensive (economic gap) and cultural or attitudinal issues around the use of public transport (cultural/attitudinal gap). The development and contribution of exible transport services can be assessed from either a top-down or bottom-up perspective. In a top-down approach, the role of exible transport services is clearly dened as part of government policy and/or planning documents and supported by funding agencies. In contrast, some exible services may be operator-led, where the original motivation is to reduce operational inefciency by reducing the number of lightly loaded buses, even when the government species the level of service and subsidises operations. The remainder of this section considers experience from Australia, Europe and USA. 2.1. Australia In Australia, the federal government does not fund public transport operations, although its role and policy interest in social inclusion, urban planning and public transport are increasing. State governments fund scheduled bus and train services, under institutional and legislative frameworks which vary from State to State. The local government sector does not have a legislative role in the provision of public transport, but many local governments are lling the gap in State funded public transport, by funding exible transport services which often focus on reducing the cost of travel to users but these are typically for a restricted user group. The experience in

Australia is therefore State and local government dependent with no over-arching pattern visible in the provision of FTS. Open access services FTS in Australia are rare, despite the preponderance of low density markets where FTS might appear to be appropriate. Whilst all States have Community Transport services, albeit organised in different ways, these have not developed or become integrated into open access services (Daniels & Mulley, 2012). Currie (2007) reviews FTS across the country and notes how the majority of exible transport services have been abandoned, with nancial performance a major challenge. Only three well-known open access FTS still operate in Australia: Telebus in Melbourne Victoria, Roam Zone in Adelaide South Australia, and Flexibus in Canberra ACT. Currie (2007) identies the common characteristics across these three exible bus services as offering simplied operations at low cost for a low density market including many to one operations, conned small catchments, and mature residential areas. Telebus in the outer suburbs of Melbourne is noteworthy for its longevity, having been introduced in 1978 (Usher, 1978, 1994). Since Currie (2007), there has been the implementation of other FTS but on a small scale such as LocalLink in Queanbeyan near Canberra and LocalLink on the South Coast of NSW (Daniels & Mulley, 2012). Flexible taxi services, particularly in Queensland, are discussed by Logan (2007) giving examples of a taxi service that uses spare capacity to provide some of the urban public transport network (Mackay Taxi Transit Service) and taxis providing FTS (Council Cab in Queensland). Other examples include local government subsidising shared taxis with the shared taxi service being booked by the local government Council as hirer (Willoughby Council, NSW). 2.2. UK and Mainland Europe Historically, across Europe, stemming from disability legislation, there has been a network of conventional public transport for the able bodied supplemented by large scale exible specialist transport for disabled and elderly people. This duplication of service has proven very costly to support. Over the last decade there has been an ongoing shift of focus from accessibility for disabled persons to accessibility for all, with specialised exible transport services considered as a complement to accessible public transport (see Nelson, Wright, Masson, Ambrosino, & Naniopoulos, 2010). The main barrier to achieving this has been the need for conventional bus services on the mainstream routes to be accessible to the disabled. In the UK, the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (DDA, 1995) required that from 2001 all new buses and coaches which can carry more than 22 passengers and are used to provide a local or scheduled service must be accessible to disabled persons, including wheelchair users. In 2006 only 56% of the UK's bus eet was low oor (Department for Transport (DfT), 2010) with signicantly lower proportion in rural areas. This clearly created a barrier to integrating elderly and disabled into the mainstream public transport. However, as of October 2010, 89% of the UK's bus eet was low oor (Department for Transport (DfT), 2010) making this goal more achievable. Some countries have been more successful at integrating elderly and disabled into the mainstream public transport. Sweden is a good example between 2004 and 2010 the Kolla project (www. kolla.goteborg.se) has introduced a package of measures aimed at implementing accessible public transport that is less costly but that reaches more people. The Swedish model required that all xed route services use low oor accessible vehicles. There should be a eet of accessible exible services for the public which complement the xed routes in low demand situations (rural feeders at peak times and area wide evening services). This resulted in the situation where 98% of citizens were able to use the accessible public transport and a limited specialist exible service is provided only for the severely disabled.

C. Mulley et al. / Research in Transportation Business & Management 3 (2012) 311

From the early 2000s the UK government sponsored a series of bus challenge programmes which resulted in the widespread development of telematics-based FTS which drew heavily on European experience (Ambrosino, Nelson, & Romanazzo, 2004). This resulted in the emergence of a signicant number of open access FTS in rural areas. However, more than half of those funded through this scheme have since been discontinued. It is worth noting that those that have survived tend to provide connection with accessible xed route services on the main corridors (e.g. Interconnect in Lincolnshire and Connect2Wiltshire). 2.3. USA The USA has signicantly more experience with FTS than any other country or region of the world. Due to lower urban population densities than in Europe, in part a consequence of extensive suburbanisation of metropolitan areas, conventional xed route public transport has always had a limited market appeal in all but a small number of large metropolitan areas. Seeking to provide a form of public transport better suited for the often low density service environments in the USA, FTS were introduced as demand responsive transport services approximately 40 years ago, and by the 1980s had become widespread. It quickly became apparent that FTS were relatively expensive compared to productive xed route public transport operations due to its limited service productivities, but in small cities or low density suburbs it was often difcult or impossible to devise productive xed route service and hence FTS were frequently the preferred service option. Most passengers embraced FTS as well due to their higher level of service compared to conventional xed route public transports. By the early 1990s, however, a sharp bifurcation developed in the pattern of FTS deployment in the USA, with the distinction being between metropolitan and non-metropolitan areas. FTS are widespread in non-metropolitan areas in the USA. The predominance of these FTS over 550 are general public services has operated since the 1970s or 1980s. In addition, over 200 other FTS systems whose ridership is restricted to a subset of the public, typically based upon age or physical disability, are operating in non-metropolitan areas. Moreover, many of the more innovative approaches to FTS have been implemented in non-metropolitan areas (Koffman, 2004). The situation is totally different in metropolitan areas (of all sizes) in the USA, where there is very little deployment of FTS for the general public. In all but a handful of the 100 largest metropolitan areas, FTS are restricted to the disabled population. There are a few notable exceptions to this trend, such as the general public FTS of the Denver and Dallas regional public transport systems (Teal & Becker, 2011) and municipal-based FTS operations in the Los Angeles, Chicago, and San Diego metropolitan regions. Overall the picture is one of almost no use of FTS by the larger public transport organisations in the USA. As a result, the market opportunity for FTS has become highly skewed. 3. Barriers to implementing exible transport services The previous section makes clear that FTS are extensively used in the USA to meet the needs of communities, particularly where there is insufcient demand to make a conventional xed schedule service a productive service. In the UK and mainland Europe there are similar examples of FTS being used to service low demand areas. Disability legislation appears to have been the reason behind the initial implementation of FTS in many cases even if subsequent implementation has responded to other drivers. Australia too has strong disability legislation and land use density similar to the USA and yet there is little evidence of FTS being used to service areas of low demand. Using the categorisation of barriers identied by Daniels and Mulley (2012) in NSW, Australia, this section describes each barrier briey before

turning to the international experience which highlights the similarities and differences in each barrier for the different parts of the world considered in this paper. 4. Institutional issues policy, legislation and regulation Institutional factors can determine the ease in which FTS can form part of the public transport mix as open access services. In principle, there is a continuum in institutional environments ranging from the on-the-road competition between transport operators, as in the deregulated environment in the UK, through to the multi-modal regional planning which is often seen in mainland Europe. Other countries fall in between these extremes. In addition, whether or not public transport planning policy recognises a role for FTS can make a difference to the legislative and regulatory frameworks in place for public transport and whether this is conducive to operating FTS or not. Policy frameworks impinging on the propensity to see FTS as part of the public transport mix often come from outside the transport policy arena. In particular, many countries have implemented disability discrimination legislation which has led to many FTS being developed to meet this transport challenge but such legislation, when not introduced into mainstream transport services, has also made the development of access for all FTS more difcult because of more stringent requirements for vehicles. The social inclusion agendas being developed in many countries, recognising the central role of transport in providing accessibility, has increased the visibility and potential for FTS in reducing transport disadvantage. Perceived or actual competition between FTS and other modes of public transport offering exible services, such as taxis and Community Transport can create signicant barriers to the introduction of services. Taxis are typically commercial operations and see FTS as a threat to their business, operating at public transport fares but offering a taxi-like service. Community Transport services can perceive FTS as impinging on their core services of meeting the spatial and physical accessibility gaps, even when Community Transport is restricted in the customers that they may service. In Australia, it is the State governments that are responsible for mass transit policy and funding. A common element of these frameworks is often rigid denitions of modes. For instance, in NSW bus operators must operate to a timetable with xed stops, and cannot charge a fare unless accredited. Bus operators are funded by the State government to provide scheduled route services, and services to school for children. Innovative, exible services developed by bus operators and open to the public are difcult to develop. In Victoria, the long standing Telebus FTS began as a fully exible transport service but was forced to introduce stops in order to meet interoperability in fares introduced by the State government. Likewise, the FTS LocalLink services in two areas of NSW are required to have timing points at stops in order to comply with the legislation for public passenger transport under the NSW Passenger Transport Act 1990. Australian cities have signicant numbers of low density communities with associated low demand. This is particularly true of growth areas where greeneld site development is not conducive to service by the conventional public transport offer. The regulatory environments have evolved to reect the environment in which conventional services primarily provide school services in these low density environments and provide the baseline public transport offer. There are recent signs that State governments, such as the ACT, are beginning to consider the provision of exible services for areas as they start to grow (Denmark, 2011). In the UK, the regulatory framework has been a key barrier to the development of exible transport services. The bus industry in the UK was deregulated following the Transport Act (1985) and, following this legislation, entry restrictions have been minimised with a view to creating free market conditions. In short, the legislation required only that operators of passenger service vehicles (service buses and

C. Mulley et al. / Research in Transportation Business & Management 3 (2012) 311

coaches) must meet safety regulations (for vehicles and operators) and then services not requiring subsidy can be simply registered which denes the route, timings at stops and fares. Services requiring subsidy have to meet the same safety regulations and route registration but their operation is consequent on an award of a competitive tender. Until the early 1990s the regulatory framework in the UK did not recognise exible services and the requirement to register the route, as described above, was not possible until the Transport Act (2000). This included measures to relax constraints on the development of exibly routed bus services by allowing the registration of certain types of variable route services and enabling these FTS to claim same grants and concessions as xed routes (Department for Transport (DfT), 2002). However these tweaks to legislation designed for conventional bus services had the unfortunate effect of making an already complex situation even more complicated. The outcome was no less than eight legislative routes to providing FTS, each with different rules for the passengers which could be carried and grants/tax rebates which could be received by operators. For example, an FTS involving a exible portion of bus route for restricted hours in the day could be provided by a licenced PSV operator under the Transport Act (2000), but if provided by a Community Transport operator using volunteer drivers then different permits were required and entitlements to claim grants and concessions differed, or if provided by a taxi operator using a vehicle with less than 8 seats then a different legislation comes into play. Given the complexity of the choices for providers, there have been many problems with interpretation and application of the legislation relating to FTS. In an effort to simplify matters and reduce the legislative barriers to providing FTS, the Local Transport Act (2008) made a number of amendments to previous legislation (primarily the Transport Act, 1985, 2000) relating to the way in which public and Community Transport services are planned and operated. The 2008 Act relaxes restrictions on the sizes of vehicles that may be used by Community Transport providers and allows drivers of community bus services to be paid. In particular, it aimed to create a more level playing eld to allow community transport and taxi operators to be entitled to the same subsidies and opportunities as commercial PSV operators (see Halcrow Group, 2009). The situation in Europe is summarised by Kalliomaki, Eloranta, and Sassoli (2004) who note that in most countries there is no legislation for FTS. They argue that without clear juridical status with other forms of public transport the real potential of FTS cannot be achieved, although the largely regionally based public transport operations have allowed FTS to be introduced successfully (as in Italy, Finland and the Netherlands). In the USA, the primary funding and decision making about public transport is at the level of local government, although many State governments have funding programmes for local public transport, often with special provisions for metropolitan regions. Although the federal government does provide capital assistance to public transport entities, the bulk of the funding for public transport originates at the local level and decisions about the type of service to provide are universally the purview of the local public transport authority and its local political overseers. The adoption of FTS in the USA has been shaped decisively by two types of legislative and policy developments. First, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 requires the provision of comparable paratransit (demand responsive) services for individuals with disabilities who are unable to use xed route public transport. This legislative mandate has resulted in the development of nearly 200 ADA paratransit services. While the ADA paratransit mandate has obviously been a facilitator of FTS of a certain type, it has also served to impede more wide-scale adoption of FTS as a result of the high costs of these special purpose FTS operations and their disproportionate claim on the public transport authority's resources. In 2004 the

operating cost per trip for paratransit service was $22.14; for all other modes, the operating cost per trip was $2.75 (Chia, 2008). At the same time, State level transit subsidy programmes have had an equally large impact on the proliferation of FTS largely in the form of general public FTS in a number of States in the USA (Cervero, 1997). California, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, and Indiana are home to over 300 FTS operations for the general public and more than 50 others with ridership restrictions. In each State, a relatively generous and long-standing programme of funds allocated to local governments for public transport purposes has enabled local authorities to implement FTS. These FTS operations are heavily concentrated in small cities, suburbs, and non-urbanised areas, where a xed route transit often performs poorly; and most systems have been in place for at least 20 years. Typically, FTS is the only public transport provided in these communities. 5. Economic issues funding issues, fares and costs to users Funding issues can create barriers through an insufcient level of funding to provide adequate subsidy for exible transport services. FTS are often seen as innovative services requiring special funding streams which are not necessarily continued into the long-term, creating a danger that FTS are only introduced as trials and expected to be sustainable or self-funding beyond the initial seed funding. In addition, the method of subsidy payment mitigates against the provision of exible transport services. If subsidy payments for conventional bus services are made according to the miles or km operated, exible transport services meet the barrier of not being able to determine in advance the level of subsidy required. For operators of FTS there is the additional risk that FTS might be more expensive, per km or per mile operated, and that this may not be covered by the typical level of subsidy for their environment. A separate set of barriers applies to the users of exible transport services. Many exible transport services are stand alone inll services with fares that are not aligned with regular passenger transport fares. Decisions as to whether users of exible transport fares should pay a premium fare for collection from or delivery to the door (as opposed to a bus stop) are often debated. For many passengers a signicant barrier is that public transport fares are expensive and the payment of a premium fare adds to the cost burden. As more cities and areas move to integrated fares with payments related to the origin and destinations, this barrier may be reduced. In Australia, conventional bus services are typically provided by private operators under contract to the State government. The form of the contract varies (whether negotiated or competitively tendered) by State. In those States where the contract is negotiated, the payment mechanism is related to the service km operated. FTS introduce uncertainty for governments as they cannot predict the nal subsidy budget with certainty. It is a signicant barrier that FTS are seen as expensive and potentially increasing the subsidy bill. In States where bus services at certain levels are competitively tendered, such as in the metropolitan area of Adelaide in South Australia, there is little incentive to introduce FTS. Despite these barriers, some of the FTS in Australia have been initiated by operators, rather than governments. Telebus in Victoria was introduced to serve a new housing development where the road dimensions were insufcient for conventional buses and has since grown to serve other areas. LocalLink in NSW was initiated by the operator as a way of reducing the costs of operation. But the approach to fares varies with Telebus charging users a premium of $1 to be collected or delivered to the door whereas LocalLink applies normal distance-based public transport fares (Daniels & Mulley, 2012). European experience suggests that the main barrier to implementing FTS is that of nancial sustainability and affordability. All exible transport services, with the exception of some niche services such as airport feeders, require subsidy. This subsidy requirement is signicant, generally above 5 per passenger trip in rural areas (see Commission for

C. Mulley et al. / Research in Transportation Business & Management 3 (2012) 311

Integrated Transport (CfIT), 2008; Laws, Enoch, Ison, & Potter, 2009). While diesel and wage costs continue to increase, budgets to fund subsidised transport services are being cut estimated to amount to a 23% cut in the budget to support subsidised services in the UK by 2014 (MVA Consultancy, 2011). Alternative providers are being increasingly sought by local authorities in the UK. As well as greater use of taxis to reduce operating costs, there is a move towards greater utilisation of the voluntary and Community Transport sector in the UK to provide reliable FTS for the general public through local authority contracts (Department for Transport (DfT), 2009, 2011). This has been made possible by a number of years of investment in community transport infrastructure by the UK Government to build capacity and to professionalise the sector by paying drivers and equipping the sector to be in a position to bid for contracted services. The advantages of this are that it offers services at a lower cost than commercial bus operators due to lower overhead costs, as well as being able to supply transport in deep rural areas. However, there are some innovative approaches to reducing the burden of subsidy. For example, the local municipality in Almada, Portugal has introduced a new service with a xed route core but on each run it allows for a limited number of pre booked deviations of up to 500 m from the xed route to pick up and drop off elderly persons from the door of day centres and health centres. Hail and ride is provided on the xed route section and this added exibility makes it unnecessary for the less able to walk the extra distance to the designated stops. This service has high patronage, attracting around 20 passengers per vehicle hour, while still providing the door to door service for those who most need it. Even with a low fare structure (0.26 per trip or 0.13 per passenger km) the farebox revenue accounts for 62% of the operating contract costs (excluding vehicle purchase cost) (Wright & Masson, 2011a). Similar to Europe and Australia, the key barrier to FTS adoption in the USA is nancial sustainability. FTS has a reputation as an expensive form of public transport, largely due to the fact that the cost per passenger trip of the typical FTS service exceeds the cost per trip for moderately productive xed route bus service (see Goodwill & Carapella, 2008). While FTS can be more cost-effective than xed route public transport, they typically are not, and thus are largely restricted to service environments where xed route services perform poorly. Even so, the relatively high costs per passenger trip of FTS means that services are often more limited than passengers prefer. Such limitations commonly take the form of a restricted number of vehicles (which means service is not always available when passengers would prefer) and restricted service hours, with little or no service during evenings and early mornings and possibly on weekends as well (KFH Group Inc., Urbitran Associates, Inc., McCollom Management Associates, Inc. & Cambridge Systematics, Inc, 2008). Several general public FTS operations in California and Michigan have existed since the 1970s, and comparing the amount of service currently with that from the earlier years of these systems reveals in virtually every case a reduction in the number of vehicles and vehicle hours of service. In a large part, this is due to State and local subsidies, particularly the former, not keeping pace with service cost increases, hence service contraction is being required to maintain nancial viability. User fares have risen signicantly for services in an attempt to reduce the impact of subsidy reductions, but with fares covering a small portion of public transport costs in the USA (typically less than 20% of operating costs except in the largest urban areas), fare increases are usually insufcient to ll the gap if subsidies from higher level government do not keep up with service cost increases. As identied above, the economic issues with ADA mandated services for the disabled have proved to be a major nancial burden for public transport authorities with knock-on effects for general access services through budget constraints. While there has been erosion in service levels over time for long standing open access FTS

operations, as noted previously, the services at least have been maintained in most communities. In some cases, however, the FTS has been transformed into a local xed route operation in an attempt to improve nancial performance but rarely due to a general increase in patronage. 6. Operational issues eet and vehicle issues Fleet and vehicle issues create operational barriers to greater implementation of FTS. This includes the nature of the existing eet of vehicles, accessible vehicles, and vehicle brokerage. Fleet proles of conventional bus operators are driven by their core business and this may give rise to vehicles unsuited to FTS operation. Acquisition of additional vehicles for FTS operation can therefore lead to additional costs associated with diverse eets such as the need to hold a greater variety of spares for maintenance and the need for more vehicles to cover engineering maintenance work. FTS vehicles tend to be smaller to permeate areas not available to conventional vehicles but do not have signicantly lower operating costs. The physical accessibility of vehicles is also a potential issue as the requirement for accessible vehicles increases costs. In virtually all developed countries disability legislation is driving the agenda for accessible vehicles which apply to both conventional and FTS vehicles. In most jurisdictions it is recognised that there is a signicant spare capacity of public transport vehicles, at certain times of day. Barriers to the greater sharing of the existing eet of vehicles between different operators exist, despite brokerage schemes for vehicles being in place. The low density environment of Australia means that the conventional bus eet, outside the metropolitan areas, is driven by the requirement to provide school services and peak period route services. This is associated with a funding mechanism that incentivises the acquisition of conventional bus vehicles. In the off-peak it is these conventional vehicles which are available and these are most suited to the provision of xed route services. The smaller vehicles used typically for FTS are not seen as being cost effective as running costs are often not much lower than conventional bus vehicles and more expensive if held in addition to the conventional eet required for the core business. In Australia, as in other countries, community groups, clubs (including the Returned and Services League (RSL) venues) and community and youth services campaign to acquire and operate their own vehicle which may be unused for signicant periods of the day or week. There are legal and other difculties in encouraging greater use of the existing eet including determining an appropriate cost to charge out vehicles to other users, ownership and insurance issues, the provision of drivers, as well as a need for information on where and what vehicles are available. Across Europe there is an increasing trend towards using taxis to provide FTS. Taxis offer an already existing vehicle resource as well as a booking capability and hence offer signicant reductions in operating costs over bus-based transport in low demand areas. A good example of this is the on demand collective (shared) taxi service on the Island of Formentera, Spain. In the non-tourist season a conventional bus service is replaced by taxi-operated FTS for local people with the choice of taxi vehicles determined by an objective to reduce cost, maximise the use of existing resources and improve the level of service for residents. In addition to cost savings of 25% there has been a reduction in CO2 emissions of over 70% (Wright & Masson, 2011b). As well as taxis providing a lower cost option to buses for individual services, there are also examples of region-wide subsidised shared taxi services such as the RegioTaxi and TreinTaxi services in the Netherlands (Mott MacDonald, 2008; Van Hamersveld, 2003) and the Collecto taxi service in Brussels (http://www.urbanicity.org/Site/ Articles/Dufour.aspx). In the UK the Commission for Integrated Transport (Commission for Integrated Transport (CfIT), 2008) presents the case for regional shared taxi provision in rural areas, but the

C. Mulley et al. / Research in Transportation Business & Management 3 (2012) 311

Government has not taken up this recommendation, even as a demonstration project. Another approach is to expand travel dispatch centres to incorporate vehicle brokerage (and vehicle booking) between for example, local authorities and the voluntary sector. Whilst this was anticipated by a number of UK authorities, it has had little success because of the difculty of integrating vehicle eets when different operators use vehicles with different vehicle standards and specications. In the USA, FTS is typically contracted out to private operators and this has had the effect of eet and vehicle issues only rarely becoming barriers to implementing such services. Federal and/or State government subsidies are usually available to purchase vehicles, and while the vehicles used to provide FTS typically are relatively expensive, often costing US$50,000$60,000 or more, such subsidies reduce the effective cost to the local authority to as little as 10% of these amounts. Moreover, the presence of three large national private sector service contractors means that even in the absence of capital subsidies for a specic local situation, the contractor has the nancial resources to purchase vehicles for use in an FTS operation. It also is important to note the way in which the three large national scale operators show interest in virtually all contracting opportunities throughout the USA, even for systems with as few as three or four vehicles; thus the local public transport authority will rarely have a problem in nding a qualied vehicle operator to implement FTS. These companies collectively operate several hundred systems. Fleet conguration represents one of the few promising areas for increasing the cost-effectiveness of FTS for the disabled, which not only improves nancial sustainability but has the benet of reducing the cost for general access FTS. In several metropolitan areas, such as Orange County, Denver, Chicago, and Dallas, the regional public transport authority has begun to utilise non-dedicated vehicles in the form of taxis to optimise the deployment of the dedicated vehicle eet. Given a highly non-uniform demand pattern, in which there are diurnal peaks and low ridership during evening hours for disabled access, the use of taxis enables the dedicated vehicle operator to operate with a relatively at service prole and reduces service production costs. This approach is not limited to FTS for the disabled, since the opportunity arises whenever there are periods where service demands, either incrementally (peak periods) or in their entirety (low volume evening service), are sufciently low that employing dedicated vehicles is less cost-effective than diverting trips to conventional taxi service. The USA equivalent of travel dispatch centres have been deployed in a limited number of areas, but have primarily been focused on brokerage approaches to regional-scale ADA paratransit services, which often involve taxi operators. There has been much discussion about such centres as a focal point for co-ordinated services involving human service agency transportation, but very little has actually occurred. Coordinated service approaches have proven very difcult to implement in the USA due to the fragmented nature of both political authority and funding sources, in the context of the typical absence of any entity with both the policy legitimacy and the nancial resources to lead the coordination system. This is an area where many regions and states have an interest, and it is likely that some travel dispatch centres whose charter extends beyond ADA paratransit will be implemented in the next 2 to 3 years. But the barriers remain formidable. 7. Attitudes, culture, perceptions and relationships between stakeholders This set of barriers is complex and relates to differences in attitudes, culture, perceptions and expectations amongst stakeholders leading to conicting approaches to public transport. On the supply side, operators of conventional public transport services perceive xed scheduled services as providing certainty for operators and the travelling public. As identied in the discussion of

economic barriers, the operation of FTS can bring uncertainty in outcome for the operator and government as the nature of the service means that the amount of provision, by responding to demand, may produce less or more funds to the operator and require more or less subsidy from the government. On the positive side, the lack of information about what FTS can offer has been recognised at a national level in the UK and USA and FTS has been publicised to operators and authorities through guidance and information documents (Department for Transport (DfT), 2006; Potts, Marshall, Crockett, & Washington, 2010). On the demand side, attitudes and cultural views on FTS create barriers. There is often a perception that the travelling public prefers the certainty of xed scheduled services as opposed to services which they need to initiate (Martikke & Jeffs, 2009). The time required to change the public's travel behaviour poses another barrier. The travelling public is not used to innovative services and it takes time to build both acceptance and patronage (Commission for Integrated Transport (CfIT), 2008; Daniels & Mulley, 2012). In Australia, the prevalence of xed scheduled route services means that operators are most comfortable with this service offer. In addition, funding arrangements mean that operators would not be able to predict with certainty the level of income they will receive in subsidy if the amount of subsidy is directly related to the amount of service provided. In NSW, for example, this leads to an asymmetry of mistrust between operators and government with both sides being uncertain about the funding outcomes. Customers are also used to xed scheduled route services even though in areas of dispersed settlements the level of service might be extremely poor. Route services are seen to be available to Australian residents in ways that FTS are not. As with all passengers, travel behaviour is slow to adjust with the operator of LocalLink services in NSW identifying that passengers needed to be trained to understand the collective nature of the service and not to treat it as a taxi service (Daniels & Mulley, 2012). In Europe, local authorities have increasingly used taxis for FTS but it is often difcult to get the taxi industry to engage in combining individual demands primarily due to the perception amongst taxi operators that shared taxi services might be less protable than the current system. In Kastoria, Greece, the local authority has overcome this barrier through establishing a co-operation agreement with the Union of Taxis consisting of 70 local taxi operators, describing the concept and the scheme of an FTS and dening the roles and responsibilities of the partners. In the UK, until relatively recently there had been few instances of local authorities awarding contracts for public FTS to Community Transport (CT) groups. CT groups relied on short-term and precipice funding arrangements made up from grants and charitable donations (see Moreton, Malhome, Jones, & Tunney, 2006). However, the relationship between CT and local authorities is now changing due to Local Transport Plans encouraging a strategic approach to community transport. More than 3/4 of local transport authorities now have a community transport strategy and the most common nancial relationship between local transport authorities and CT organisations is now through a service level agreement (SLA) to provide contracted services. The national government now actively encourages partnership working between local authorities and the Community Transport sector (Department for Transport (DfT), 2011). There sometimes remains however tension between CT and other transport providers. Within Europe, the engagement of local communities to actually use FTS is a clearly recognised barrier with too often a disconnect between the transport planners and operators and the local community. The FTS which have made a particular effort to overcome this barrier have been amongst the most successful. Ring-a-Link, for example, is a nonprot making, charitable organisation funded by the Department of Transport in Ireland, offering general access services for rural dwellers. It is underpinned by a management structure which comprises a Board

C. Mulley et al. / Research in Transportation Business & Management 3 (2012) 311

of 17 volunteer Directors who are prominent members of the community representing community groups, local authority elected representatives and staff, disability groups, farming organisations and various other Agencies. The benet of such representation is the direct links to large sections of the community that would otherwise be unreachable by the Ring-a-Link staff and has increased community acceptance (Wright & Masson, 2011b). As in Australia, a primary barrier to more extensive use of FTS in the USA is a strong cultural orientation among many public transport managers towards traditional public transport services. Most managers in metropolitan area public transport systems have little or no experience with FTS, and extensive experience with conventional xed route services. Their primary exposure to FTS has been via the ADA paratransit services operated by their organisation, and these services have been expensive, low volume headaches for the most part. Moreover, public transport managers perceive their charter to be one of providing conventional public transport services in a costeffective manner and so have not thought strategically as to how to use FTS to achieve their agency's overall objectives. There are some clear exceptions to this, such as the family of services approach used by the Denver public transport agency in using FTS to provide last mile public transport service or basic access to local residents in low density service environments (Teal & Becker, 2011). As identied above, FTS is primarily provided by a small number of national scale private providers in the USA. These organisations, together with smaller scale regional contractors where present, are an important constituency supporting FTS. However, their support tends to be passive as these organisations are usually not in a position to lobby aggressively for FTS as a consequence of their dependency on public sector clients for their income. In contrast to Europe, the local taxi industry in the USA is less of a factor in encouraging the adoption of FTS. The taxi industry in the USA has undergone a dis-integration at the local level over the past 30 years, with taxi companies devolving into loose collections of drivers with limited centralised management of operations, and the taxi company doing little more than providing a telephone number and dispatching services. The result is an uneven interest by taxi operators in obtaining FTS business from the public transport operators in their areas. 8. Information, education and promotion Information as a barrier includes information and awareness by both operators and the public of the opportunities offered by exible transport. For operators not operating FTS, there is a lack of understanding as to what FTS can offer. Alongside this, operators are comfortable with their core business but unfamiliar with what would be required to run FTS. Passengers also have a lack of understanding of how a more exible service might work and how it might impact on their accessibility. Smaller vehicles which are called on-demand feel more like a taxi service and the need to share with other public transport passengers is not understood. Marketing of FTS is one of the biggest, but overlooked, challenges facing an FTS provider. The more exible the service, the less visible it is to the passenger and the more resources and effort need to be devoted to its promotion. There is also a practical difculty in information provision that relates to the way in which exible services are stored in public transport databases used in public transport information provision. Services which are exible cannot be geo-coded and are therefore difcult to include in on-line journey planning systems, providing an additional barrier to the dissemination of their presence although text messaging is being more widely used (e.g. the MyBus services in Strathclyde). In Australia, the low incidence of FTS means that operators are not familiar with the operation of FTS. For the vast majority of passengers this is also true. Providing information for public transport where FTS

exists is not as problematic as most FTS are required to have xed stops to comply with the regulatory framework. These xed stops are built into timetable provision and information sources. In line with the experience outside Australia, Australian operators of FTS identied word of mouth as the most effective form of advertising and marketing. However, operators of Telebus and LocalLink identied the travelling public's lack of knowledge about travel options and the mechanics of use, such as timetables and ticketing, as a barrier to more public transport use in general and FTS in particular (Daniels & Mulley, 2012). This experience is repeated in Europe where the perception in many areas is that FTS is only for elderly and disabled people. There are, however, some successful experiences. ATL, the municipal public transport operator in Livorno, Italy, has been successful for many years with its marketing of FTS using a brand image of a Koala Bear consistently. In Almada, Portugal, the local authority developed an animated video tour of the FLEXIBUS service operation (http://www. m-almada.pt/exibus/). This provides a powerful means of presenting all the features of the service to potential users and can be used at public meetings arranged to raise awareness of the service. European services, when fully exible, suffer from poor representation in on-line journey planners because of the difculty in geocoding routes. This is in clear contrast to Melbourne, Australia where the exible service is represented by a dummy timetable and trip notes to explain the service to users (although this is facilitated by the service also having xed stop timings). Although some (mainly xed route) operators are starting to use Twitter and Facebook to communicate with passengers, it is increasingly being recognised that embracing and exploiting this require investment both in time and effort. An information barrier also exists when authorities and client representatives attempt to allocate users of different specialist transport services on to open access FTS. In the UK there have been numerous instances of attempts to reduce the spending on specialist transport services, particularly non-emergency patient transport services (PTS), by transferring passengers to open access FTS. However, a lack of knowledge on passenger needs and entitlements combined with insufcient information on vehicle and driver suitability has made this difcult to achieve in practice on a wider scale. In the USA, established FTS are typically community-centric and there is little need for on-going education as the local public has at least a vague sense of the service and how it functions and active users quickly become very knowledgeable about the nature of the service. With the advent of on-line information resources and, in a small number of systems, on-line reservation capability for riders, passengers can access information and even book trips on the service using their own computers. On the other hand, adopting FTS as a substitute for a poorly performing xed route operation may require the public transport authority to sell the virtues of the service to passengers who are suspicious and sometimes hostile towards such substitution. Here, education and active persuasion as to why passengers are not disadvantaged by this new, unknown service are needed, as shown by the considerable time spent by the planning staff and the policy makers of the Denver public transport agency when it decided to substitute FTS operation for poorly performing xed route bus services. It has been important to make the case to the public that the alternative to service substitution is total discontinuation of public transport service in an area, and the FTS represents a positive option in this situation. 9. Implications for managerial practice This section considers recommendations for overcoming each of the sets of barriers discussed in the previous section. In terms of institutional barriers it is clear that the legislative context can have a major impact on the prospects for FTS. Legislation that

10

C. Mulley et al. / Research in Transportation Business & Management 3 (2012) 311

implicitly assumes that public transport is inherently a xed route, xed schedule mode may impede development of FTS. The experiences in Australia and the UK illustrate that this is not merely a theoretical possibility. Similarly, the heavy legislative emphasis in the USA on providing FTS for the disabled population has created a situation in which many participants in the public transport planning and decision making system have literally no knowledge that FTS was initially developed as a transport service for the general public, and has a favourable track record as such in many smaller cities. Whether it be Europe, Australia, or the USA, the result of not according FTS full status as a form of public transport has been to increase many-fold the difculty of achieving acceptance of proposals for introducing FTS into the local public transport environment. On the other hand, when funding programmes for public transport are merely neutral with respect to their use and sufcient in magnitude, then FTS has proliferated without any special treatment, as in the hundreds of small cities in the USA that have adopted FTS as a backbone local public transport service for the general public. Consideration of economic barriers shows that in every country and region, increased adoption of FTS is challenged by the nancial performance of this form of public transport. FTS is invariably less cost-effective than higher volume xed route services, but the actual choice in service environments appropriate for FTS is typically between FTS and low volume xed route operations, and in this comparison, FTS is often quite competitive. Throughout the world, various strategies have been utilised to attempt to improve the costeffectiveness of FTS. These include more structured types of FTS such as deviated routes or checkpoints, dynamic temporal recongurations of service, etc. to obtain some of the advantages of xed route service without losing the essential characteristics of service exibility, the substitution of lower cost operators such as taxis organisations, and premium fares to reect the more personalised nature of the service. Even for socially mandated FTS, such as ADA paratransit in the USA, strong pressures have developed to improve cost-effectiveness signicantly. Public transport agencies in the USA are beginning to experiment with much more use of taxis to atten the service prole and to off-load highly unproductive trips to an alternative supplier, thereby insulating the core service operation from the corrosive impacts of an excessive amount of long, out of the way trips. In the end, it is this very exibility of FTS in terms of service structuring, service organisation, and service delivery options that represents its greatest asset in meeting the cost-effectiveness challenge. As the Denver regional public transport agency in the USA has demonstrated, an important role can be developed for FTS in selected service environments in spite of its higher cost per passenger, provided the public authorities have the proper concept of how to best use FTS and use all of the tools available to maximise its nancial performance. When addressing operational barriers, the concept of travel dispatch centres has proven conceptually attractive, and there have been a number of such centres actually implemented. But while these have been useful devices to improve service organisation and generate minor cost-efciency improvements, their impacts have been less wide ranging than hoped for. For example, a number of British authorities have anticipated that their Centres will be developed and expanded to incorporate other local authorities and the voluntary sectors to provide common booking (including transferring passengers between different providers), vehicle brokerage or both. In practice this has seldom been realised often because of the difculty of integrating services and vehicle eets as well as the failure to implement better co-ordination of back-ofce resources. A notably positive factor for FTS in the USA has been the development of the national scale private contractors. Somewhat ironically, two of these three organisations have non-USA parent companies, who themselves are major presences in the UK, European, and

Australian markets but whose non-USA operations have much less competency and experience with FTS. Due to the presence of these three companies, any public agency who wishes to implement FTS can be assured that a competent operator can be secured to operate the service. This is not a new development in the USA; multiple national scale contractors for FTS existed as early as the mid-1980s. It is clear that FTS has an international problem with respect to the attitudes of public transport operators towards this form of transport. Even 40 years after the initial introduction of FTS, many public transport managers continue to view these services sceptically. FTS are perceived as being overly expensive and difcult to operate, as offering little advantage compared to conventional xed route service. On the other hand, when FTS are sponsored by local authorities who are not public transport organisations per se, it is often viewed quite differently, and may be embraced by both public sector managers and decision makers, and local residents. There are countless examples of this in small cities in the USA. It is noteworthy that there is typically no established organisational constituency for FTS, due to their peripheral status with most public transport organisations, a few notable exceptions (such as Denver in the USA) notwithstanding. Even in the USA, the national scale operators of FTS, since they are contractors with a limited local presence, are not in an ideal position to advocate for these services. Local residents tend to be more focused on service availability than service mode, and often become strong advocates of FTS if the service becomes successfully established, but it is common for residents to identify xed route service as being real public transport if they have not had prior experience with FTS. The good news is that these perceptions can be altered in favour of FTS if an implemented system performs well. Informing and educating decision makers, the general public, and public transport users about FTS remain an important task in all regions, even 40 years after the introduction of these services. While insufcient knowledge represents a less formidable barrier to the implementation of FTS than the negative views of public transport managers, the sense that FTS are less of a mainstream form of public transport can still pose a barrier to policy and general public acceptance. Experience has demonstrated that information is usually the antidote to that problem. Educating the public about the nature of FTS and how to use the service has been an issue since the inception of FTS. With the advent of a new era in communication capabilities, there is much potential for improvement in this area. On-line information resources and booking tools make it possible to place the customer in the middle of the process of obtaining service, and to dramatically improve information ow. While public transport lags well behind other modes of passenger transport the contrast to airline travel continues to be stark in using on-line mechanisms to transact with and inform its users, it is clear that there are no technical impediments to such improvements, and only modest nancial barriers. It is still early in the process, but examples are beginning to be seen of organisations using technology to involve the user more fully and with greater immediacy in the information ow. Notwithstanding better penetration of information technology, FTS must be sensitive to their users and their capabilities with, for example, differentiated education and marketing being used for the elderly and inrm compared to youth users.

10. Conclusions This paper was motivated by the recognition that a variety of barriers existed to prevent more widespread use of FTS in NSW, Australia (Daniels & Mulley, 2012) where the territory for its implementation would seem favourable. Using the categorisation of barriers in Daniels and Mulley (2012) (institutional frameworks; economic issues; operational issues; operator and community attitudes; and nally information and education) this paper has compared and

C. Mulley et al. / Research in Transportation Business & Management 3 (2012) 311

11

contrasted the experience across Australia, UK and Europe. The key ndings include: Whether it be Europe, Australia, or the USA, the result of not according FTS full status as a form of public transport has been to increase many-fold the difculty of achieving acceptance of proposals for introducing FTS into the local public transport environment. It is the very exibility of FTS in terms of service structuring, service organisation, and service delivery options that represents their greatest asset in meeting the cost-effectiveness challenge. The concept of travel dispatch centres has proven conceptually attractive in all of the regions, and there have been a number implemented in each region (except Australia). But while these have been useful devices to improve service organisation and generate minor cost-efciency improvements, their impacts have been less wide ranging than hoped for and are currently not well equipped to facilitate wide-scale service integration. Local residents tend to be more focused on service availability than service mode, and often become strong advocates of FTS if the service becomes successfully established However, it is common for residents to identify xed route service as being real public transport if they have not had prior experience with FTS. While insufcient knowledge represents a less formidable barrier to the implementation of FTS than the negative views of public transport managers, the sense that FTS is less of a mainstream form of public transport can still pose a barrier to policy and general public acceptance. The paper has explored the way in which the barriers experienced in Australia have been encountered and tackled in the USA and Europe so as to make recommendations for managerial practice that would enable and encourage greater use of exible transport services by transport service planners and providers in all countries, not only in Australia. References

Ambrosino, G., Nelson, J. D., & Romanazzo, M. (Eds.). (2004). Demand responsive transport services: Towards the exible mobility agency. Rome: ENEA. Cervero, R. (1997). Paratransit in America: Redening mass transportation. Connecticut, USA: Praeger. Chia, D. (2008). Policies and practices for effectively and efciently meeting ADA paratransit demand. A synthesis of transit practice, TCRP Synthesis 74, Washington, DC available at: http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/tcrp/tcrp_syn_74.pdf Last accessed 10.04.12. Commission for Integrated Transport (CfIT) (2008). A new approach to rural public transport. London: Commission for Integrated Transport Available at http:// webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110304132839/http://ct.independent. gov.uk/pubs/2008/rpt/report/index.htm Currie, G. (2007). Demand responsive transit development program report nal report. Institute of Transport Studies, Monash University. Daniels, R., & Mulley, C. (2012). Flexible transport services: Overcoming barriers to implementation in low density urban areas. Urban Policy and Research, 30(1), 5976. Denmark, D. (2011). Flexible transport services review for ACT Department of Territory and Municipal Services. Available at http://www.transport.act.gov.au/referencesdocs/Draft%20Coverage%20Service%20Deliver%20Study%20-%20Appendix%20A.pdf Department for Transport (DfT) (2002). The exible future. Available at http://webarchive. nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/ http://www.dft.gov.uk/consultations/archive/2002/frbs/ Department for Transport (DfT) (2006). Good practice guide for demand responsive transport services using telematics. Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle University. Department for Transport (DfT) (2009, April). Providing transport in partnership A guide for health agencies and local authorities. London: Department for Transport Available at http://www.dft.gov.uk/pgr/regional/ltp/guidance/localtransportsplans/ policies/communitytransport/transportinpartnership/ Department for Transport (DfT) (2010, October). Annual bus statistics 2009/2010. London: Department for Transport Statistics Available at http://www.dft.gov.uk/ pgr/statistics/datatablespublications/public/bus/ Department for Transport (DfT) (2011, March). Community transport: Guidance for local authorities. London: Department for Transport.

Derek Halden Consultancy (DHC) (2006). How to plan and run exible and demand responsive transport guidance. Derek Halden Consultancy (DHC), The TAS Partnership and the University of Aberdeen. Transport Research Planning Group, Scottish Executive Social Research Available at http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2006/ 05/22101418/0 Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) (1995). Disability Discrimination Act 1995. UK. Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1995/50/data.pdf Enoch, M., Potter, S., Parkhurst, G., & Smith, M. (2004). INTERMODE: Innovations in demand responsive transport, nal report. Available at http://design.open.ac.uk/ potter/documents/INTERMODE.pdf Ferreira, L., Charles, P., & Tether, C. (2007). Evaluating exible transport solutions. Transportation Planning and Technology, 30(23), 249269. Goodwill, J. A., & Carapella, H. (2008). Creative ways to manage paratransit costs. University of South Florida: National Center for Transit Research (NCTR) Available at http://www.nctr.usf.edu/pdf/77606.pdf Last accessed 12.04.12. Halcrow Group (2009). The Local Transport Act Effectiveness in rural areas. Report for the Commission for Rural Communities. Kalliomaki, A., Eloranta, P., & Sassoli, P. (2004). Organisational, institutional and juridical issues. In G. Ambrosino, J. D. Nelson, & M. Romanazzo (Eds.), Rome: ENEA. KFH Group Inc., Urbitran Associates, Inc., McCollom Management Associates, Inc., & Cambridge Systematics, Inc. (2008). Guidebook for measuring, assessing, and improving performance of demandresponse transportation. Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board. Koffman, David (2004). Operational experiences with exible transit services. TCRP Synthesis, 53, Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board. Laws, R., Enoch, M., Ison, S., & Potter, S. (2009). Demand responsive transport: A review of schemes in England and Wales. Journal of Public Transportation, 12(1), 1937. Local Transport Act (2008). UK. Available at http://www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2008/ ukpga_20080026_en_1.htm Logan, P. (2007). Best practice demand-responsive transport policy. Road and Transport Research, 16(2), 312. MacDonald, Mott (2008). The role of taxis in rural public transport, Appendix C Case study reports. Report prepared for The Commission for Integrated Transport. Martikke, S., & Jeffs, M. (2009). Going the extra mile: Community transport services and their impact on the health of their users. Report for Greater Manchester Transport Resource Unit, July 2009 Available from: http://www.gmcvo.org.uk/sites/ gmcvo.org.uk/les/Going%20the%20Extra%20Mile.pdf; last visited 10/04/12. Moreton, R., Malhome, E., Jones, A., & Tunney, F. (2006). Enterprising approaches to rural community transport. : Plunkett Foundation and the Community Transport Association Available from: http://www.plunkett.co.uk/whatwedo/RCT.cfm; last visited 10/04/12. MVA Consultancy (2011, August). Modelling bus subsidy in English metropolitan areas. Report for Passenger Transport Executive Group. London: MVA Consultancy. Nelson, J. D., & Phonphitakchai, T. (2012). An evaluation of the user characteristics of an open access DRT service. Research in Transportation Economics, 34, 5465. Nelson, J. D., Wright, S., Masson, B., Ambrosino, G., & Naniopoulos, A. (2010). Recent developments in exible transport services. Research in Transportation Economics, 29, 243248. Potts, J. F., Marshall, M. A., Crockett, E. C., & Washington, J. (2010). A guide for planning and operating exible public transport services. Transportation Research Board, TCRP Report, 140. SAMPO (1997). Systems for advanced management of public transport operations. Available at http://www.cordis.lu/telematics/tap_transport/research/projects/ sampo.html last visited 10/04/12. Teal, R. F., & Becker, A. J. (2011). Business strategies and technology for access by transit in lower density environments. Research in Transportation Business and Management, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2011.08.003. Transport Act (1985). UK. Available at http://www.opsi.gov.uk/RevisedStatutes/Acts/ ukpga/1985/cukpga_19850067_en_1 Transport Act (2000). UK. Available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/38/ contents Usher, J. (1978). Possibilities for demand responsive bus operation in outer suburbs. Papers of the 4th Australian Transport Research Forum, Perth www.patrec.org/atrf. aspx Usher, J. (1994). Remember Telebus? The Rowville report. Papers of the 19th Australasian Transport Research Forum, Lorne www.patrec.org/atrf.aspx Van Hamersveld, H. (2003). A new collective public transport system, Regiotaxi KAN. Paper presented at the European Transport Conference 2003 Available at http://www.etcproceedings.org/paper/a-new-collective-public-transport-systemregiotaxi-kan. Wright, S., & Masson, B. (2011). Cross site evaluation report (D8), FLIPPER project. Available at http://srvweb01.softeco.it/ipper/_Rainbow/Documents/FLIPPER_D8_ Cross_Site_Evaluation_141011.pdf last visited 10/04/12. Wright, S., & Masson, B. (2011). Good practice guidance report (D9), FLIPPER project. Available at http://srvweb01.softeco.it/ipper/_Rainbow/Documents/FLIPPER%20D9_ Good%20Practice%20Guidance_310811.pdf last visited 10/04/12.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Weldability of Cr-Mo SteelsДокумент20 страницWeldability of Cr-Mo SteelsNitin Bajpai100% (2)

- 4 - Lec 3 - 1 MaterialДокумент55 страниц4 - Lec 3 - 1 MaterialMohd Shukri IsmailОценок пока нет

- Saep 309Документ22 страницыSaep 309brecht1980Оценок пока нет

- Tolerance ManualДокумент187 страницTolerance ManualRenish RegiОценок пока нет

- 1019spm S7000re L03Документ12 страниц1019spm S7000re L03Farid TataОценок пока нет

- Painting Coating Selection Guide PDFДокумент1 страницаPainting Coating Selection Guide PDFNageswara Rao BavisettyОценок пока нет

- TYPES OF TERMINALS IN PORTSДокумент55 страницTYPES OF TERMINALS IN PORTSOltan Uzun100% (1)

- Ronda Pilipinas Race ManualДокумент198 страницRonda Pilipinas Race ManualRonda PilipinasОценок пока нет

- (12.2.624) Aviation Refueling Business: A Goldmine of OpportunitiesДокумент6 страниц(12.2.624) Aviation Refueling Business: A Goldmine of OpportunitiesMuhammed SulfeekОценок пока нет

- URA Elect SR 2005 03Документ55 страницURA Elect SR 2005 03Zhu Qi WangОценок пока нет

- Bill of MaterialsДокумент6 страницBill of MaterialsJames Howell Nacion50% (2)

- Agenda Cbe 2012Документ22 страницыAgenda Cbe 2012Santhoshkumar RayavarapuОценок пока нет

- Factors Affecting Subcontracting StrategyДокумент12 страницFactors Affecting Subcontracting StrategyAbdulrahman NogsaneОценок пока нет

- Fabrication of Steel Structure and Steel Equipment (Itp)Документ4 страницыFabrication of Steel Structure and Steel Equipment (Itp)Javed MAОценок пока нет

- Mining TermsДокумент8 страницMining TermsAbhijit PandaОценок пока нет

- Granberg Precision Grinder G1012XT ManualДокумент2 страницыGranberg Precision Grinder G1012XT ManualAnonymous GtkD9AEJqeОценок пока нет

- Staufen Polska One Piece Flow 2009Документ4 страницыStaufen Polska One Piece Flow 2009tiwintli14Оценок пока нет

- OIL POLLUTION SURVEYSДокумент3 страницыOIL POLLUTION SURVEYShlekakisОценок пока нет

- Non WovenДокумент24 страницыNon WovenAbdullah Al Hafiz0% (1)

- Pipefitter.com - One Stop Shopping for Pipe Fitting Books and ToolsДокумент7 страницPipefitter.com - One Stop Shopping for Pipe Fitting Books and Toolsprimavera1969Оценок пока нет

- Boegger Industrial LimitedДокумент7 страницBoegger Industrial Limitedshusongdai78Оценок пока нет

- LNG 01Документ24 страницыLNG 01Abhijeet Mukherjee100% (1)

- AISI 1020 Low CarbonLow Tensile SteelДокумент3 страницыAISI 1020 Low CarbonLow Tensile SteelNaman TanejaОценок пока нет

- How To Weld T-1 SteelДокумент21 страницаHow To Weld T-1 SteelMuthu Barathi ParamasivamОценок пока нет