Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Shakespeare's Son-in-Law John Hall by Arthur Gray (1939)

Загружено:

TerryandAlanАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Shakespeare's Son-in-Law John Hall by Arthur Gray (1939)

Загружено:

TerryandAlanАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

SHAKESPEARE'S

SON-IN-LAW

JOHN HALL

By ARTHU.R GRAY, M.A.

Master of Jesus College, Cambridge

CAMBRIDGE

W. HEFFER & SONS LTD.

1

939

'"

>fSW

First Published in 193 9

PRINTED AND BOUND IN GREAT BRITAIN AT THE WORKS

W, HIEP'FER a SONS LTD., CAMBRIDGE, ENGLAND

Shakespeare s Son-in-Law

O

N June 5, 1607, John Hall, gentleman, was

married at Stratford church, to Susanna Shake-

speare.

Susanna, his elder daughter, was evidently Shake-

speare's favourite. The ample provision which he

made in his will for her and her husband and issue is in

marked contrast with the hesitating bequests which

he makes to her sister, Judith, and her husband,

Thomas Quiney, who in his later life proved so un-

satisfactory. John and Susanna were executors of

Shakespeare's will, and to them he devised his freehold

properties in London and at Stratford. Their only

child, Elizabeth, was born in February, 1 6o8.

"Something there was of Shakespeare," perhaps, in

John, as well as in Susanna. We should like to know

the man who, in h1s medical capacity, cared for the poet

in his retirement, and must have taken daily part in

conversation with him, and conceivably, imparted

something of his experience and character to the pro-

duction of the plays. Just possibly, some likeness of

him may be intended in Cerimon, the benevolent

physician of Pericles (I 6o8), but the portrait has no

individual features. If little positive evidence be

forthcoming of the relation between the two men

during the years when both were living at Stratford, it

might be expected that from documents some evidence

might be forthcoming to satisfy some obvious questions

about Hall. What of his family and birthplace, his

I

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

education, when did he settle at Stratford, and what

induced him to start a medical practice there?

In the amplitude of its records concerning the lives

and conditions of even its least distinguished citizens,

Stratford has perhaps as much to tell as any town in

England in the period I 590- I 6 3 5. And Hall was

by no means among the least distinguished. In the

town and neighbourhood his reputation stood almost

as high as Shakespeare's. And what does Stratford

tell of the one man more than the other?

Extracted from a bewildering heap of pure guess-

work the following facts are all that Sir E. K. Chambers

could unearth when he wrote his biography of William

Shakespeare in I 930. John Hall was somehow con-

nected with Acton, Middlesex, where he owned a

house, which he bequeathed to his daughter, Elizabeth.

He was elected in his absence and without his consent

to the Town Council of Stratford, and was displaced

for non-attendance. His age at death (I 6 3 s), as

stated on his monument, was "6o," and he himself

notes that in August, 1632, he was about 57 He was

described as M.A. (in Artibus Magister). As Strat-

fordian biographers naturally postulated that a West

Country man would go to the nearer University, it

was assumed that he was a certain John Haule who

graduated M.A. at Oxford in I 598 and was of

Worcestershire. But the arms of the Worcestershire

family were not those displayed on the Hall monument

at Stratford Church. Sir E. K. Chambers prudently

remarks "the name is too common to make any con-

clusion more than tentative." In the register of

John Hall's burial he is described as medicus peritissimus,

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

3

"a physician greatly skilled." So far as is known he

had no licence to practise medicine at Stratford or

elsewhere.

But there exists a notebook, written in Hall's hand

and now in the British Museum, of cases attended by

him in his later years, which proves that he had a wide

practice and many distinguished patients. After

Hall's death this book fell into the hands of a pro-

vincial physician, J ames Cooke, who edited it, with

additions of his own, as Observations of English Bodies,

I 6 3 7. One of his notes is that Hall had travelled and

"was acquainted with the French tongue." The

significance of the remark is illustrated by the dis-

coveries made by Mr. I. E. Gray and published by

him in the Genealogical Magazine of September, I 936.

The evidence collected by Mr. Gray is attested by

contemporary documents, collected from many sources,

and leaves no question that the subject of his enquiry

was indeed the John Hall who married Shakespeare's

daughter.

The key that opened the enquiry came from an

altogether neglected quarter. In the invaluable

Alumni Cantabrigienses of the late Dr. John Venn, a

register of admissions and degrees from the earliest

times, occur the following notes :

HALL, DivE. Matric. pens. from QuEENs', Mich. I 589. Of

Bedfordshire.

HALL, JoHN. Matric. pens. from QuEENs', Mich. I 589. Of

Bedfordshire. B.A. I 593-4, M.A. I 597, as Hale.

In college admission books the county stated is in-

variably that of birth. The fact that both brothers

were pensioners indicates that they were of some social

+

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

standing. Of Dive, more will presently be said. The

remarkable thing in his admission is his Christian

name. It is the surname of a well-known family

living at Bromham in Bedfordshire. Dive may have

been related-possibly a god-son of either Sir Lewis

Dive (d. 1592) or of Sir John Dive (d. 16o7).

The clue offered by John Hall's ownership of the

house at Acton of course had to be followed up. But

the parish register of that place contains no entries of

Halls who could reasonably be connected with the

Bedfordshire family. A flood of light on their origin,

occupations and interests comes from the will of a

certain William Hall "of Acton in the Countye of

M1dd.," dated December I 2, I 607. The testator

was buried at Acton on the following December 2 I.

WILL OF WILLIAM HALL OF ACTON,

MIDDLESEX, GENT.

DATED I 2 DEcEMBER I 6o7

(P.C.C.)

In dei nomine Amen, I William Hall of Acton in the Countye

of Midd. sicke in bodye but of a perfect memorye and

understandmg I thanke god Do ordayne, constitute and make this my

last will and testament in manner and forme folowing. First I

bequeathe my bodye to be buryed in the churche of Acton if I dye

there or in the churche elswhere. My soule I bequeathe unto the

Almightie god whoe hathe created me and gave his sonne to redeeme

me and _therfore he is wholly myne by whose deathe passion and

resurrectiOn I only truste to be saved, and by noe meritte of myne

owne, for he hathe given me of his spiritt sufficiently to call me to

repentaunce for all my former synnes, and hathe given me grace

steedfastly to beleve in hym and unto suche he hathe promised no

condempation but life everlasting saying: Whosoever repenteth and

beleeveth in me I will give hym life everlasting, thoroughe which

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

5

promise my faithe ys fortified and confirmed. For the whiche I give

hym humble thankes and so I take the whole Cupp of Salvation of

hym with thankes gyving for ever and ever Amen. Concerning my

earthlie goodes I ordayne as foloweth. As concerning my eldest son ne

Dive forasmuche as he requyred his portion longe agoe the whiche ye

receyved and bound hym selfe in a bond to demaunde any more as

appeareth by his bond obligatorye in this house, as allso the many

unkyndnes which he showed unto me heretofore and especially synce

the deathe of his mother; Notwithstanding in regard that he is my

sonne I bequeathe unto hym as a legacey fortie shillings. Item I give

unto the poore of Acton fortye shillings to be distributed by the church-

wardens and cunstables of the parishe of Acton equally where most

neede ys. Item I give and bequeathe to my daughter Elizabeth Sutton

tenne poundes conditionallye that she give the sayed tenne poundes

with her sonne William Sutton to bynde hym an apprentise; Because

they have kept hym home at his owne will and would not suffer hym

to profitt while he mighte, and nowe of necessitie is constreyned to be

put an apprentise because he will not give hym selfe to any other

profession. Furthermore I give and bequeathe unto my sayed

Daughter Sutton twelve poundes conditionally that she shall distribute

yt equally betwene her children called Randall, Mary and Elizabeth

at the ages of eightene yeres ould or at the dayes of theire marriage,

whiche of bothe shall first come. And yf it please god to take any

of theise before the sayed time theire portion so dying shall remayne

to the rest lyvinge equally distributed. And in defaulte of them all

before the forsayed tyme: Then that yt should all remayne whollie to

William Sutton her eldest sonne. And in his defaulte to remayne

whollie to my daughter Welles children successively. Item I give and

bequeathe to my daughter Sara Sheppard fiftie poundes to be receyved

and had from my executors within the space of one halfe yere after

the deathe of her husband that now ys to witte William Shepparde

Doctor of phisicke. Item I give and bequeathe to my daughter

Martha Barlowe nowe wife of Benjamyn Barlowe, one hundred and

twentie poundes, to be receyved from the executor or executors within

the space of one quarter of a yere after the deathe of her said husbande

Benjamyne Bar!owe. Item I give and bequeathe to my sister Cicely

Carter twentie nobles to be payed unto her within one quarter of a

yere after my deceasse. Item I give and bequeathe to my sister

Knighte her sonne, twentye nobles, to be payed unto hym within one

quarter of a yere after my deceasse. Furthermore I give and bequeathe

unto my man Mathewe Morris all my bookes of Astronomye and

6 SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

Astrologie whatsoever conditionally that yf my sonne John do intende

and purpose to laboure studdye and endevor in the sayed Arte, that

the sayd Mathewe should instruct hym in consideracon of his Mr. his

benevolence and free guift. Further I give and bequeathe unto the

sayed Mathewe Morris fower poundes of good and lawfull money to

be payed unto the sayed Mathewe within three moneths after my

deceasse and the foresayed bookes presently after my Deceasse.

Furthermore I give and bequeathe to my mayde Anne Gouldstone that

nowe ys thirtie shillings to be payed unto her within one moneth after

my deceasse. All the rest of my goodes, debts as well by bonde due

as otherwise and all houses, landes, leasses, tenements or whatsoever

myne or due unto me, I give and bequeathe unto my sonne John Hall

whome I make my sole executor of this my last will and testament

condicionally that the sayed John shall dischardge paye or cause to be

executed, discharged and payed the abovenamed legaceys according

to the true intent will and meaning of me the Testator, as allso to

dischardge my funerall expenses and debts. In witnesse whereof I

have putt to my hande uppon the twelveth daye of December in the

f}'veth yere of the Raign of James by the grace of god kinge of England,

France and Ireland and of Scotlande the one and fortithe and in the

yere of our Lord god 1 6o7. Provided further that yf my sayed sonne

John do refuse to be executor and to paye the legaceys abovewritten

That then my sonne Dive should take uppon hym the foresayed

execution of my testament; my will ys paying unto my sayed sonne

John fiftie poundes togither with all my bookes of phisicke, to be

payed unto the sayd John within one or twoe moneths after my deceasse.

Further I give and bequeathe all my bookes of Alchimye unto my

foresaid servaunt Mathewe Morris, to be payed and given presently

after my deceasse unto hym. Allso I ordeyne and constitute that my

executor whosoever shall paye or cause to be payed all my debts

whatsoever and execute and contente all Demaundes whatsoever.

Moreover yf neither of may sayed sonnes will be executor: then my

will ys that my sonne Michaell Welles should be executor paying to

my son John and the Rest the aforesaid Legaceys before rehersed

together with my Debt and funerall expenses. Allso my will ys that

yf neither of my Sonnes be executor, that then my sonne Sutton and

my sonne W elles should be Overseers. And yf my sonne W elles be

executor that then my sonne John Hall and my sonne Sutton should

be overseers. In witnesse whereof (That this is my true and laste will

and testament) I have putt to my hande and seale the Daye and yere

abovewritten per me Guilielmum Hall.

~ ... ,.... .c

~ - '11 .....

I

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

7

John Hall was clearly not present when the will was

drawn; otherwise the doubt as to his acceptance of

the executorship would not have arisen. He had been

married to Susanna Shakespeare in the previous June

and, no doubt, professional duties kept him at Strat-

ford, just as, at a later time, they prevented his

attendance at meetings of the Town Council. He

proved the will on December 24, I 607, but declined

to act as executor, and in accordance with the will,

his brother, Dive, acted in his room. Dive died at

Acton, apparently in his brother's house, in I 626,

and by his nuncupatory will left all he had to his

relation, Michael W elles. In I 6 2 9 there was

Chancery litigation between John Hall, of Stratford,

gent., and Michael W elles, of Glatton, Hunts. Hall

states that he renounced the executorship of his

father's will "in regard it would be a hindrance in his

profession of being a physician."

From the particular mention in his will of "books of

physic" it would appear that William Hall was a

practitioner in medicine at Acton, then a suburban

village within the jurisdiction of the Royal College of

Physicians. Whether he had a medical degree or was

licensed by that body is unknown. The value which

he attached to his books of Astrology, Astronomy and

Alchymy proves that he had been trained in a school of

medicine which was old-fashioned in I 6o7 but had been

highly popular forty years earlier, when the great

physician, J erome Cardan, associated those sciences

with his medical teaching. We gather from his will

that he was a convinced Protestant.

Dive and John were apparently his only sons

8 SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

surviving in 1607. He had several married daughters

who, with their husbands and families, are mentioiJed

in the will. His most notable son-in-law was William

Sheppard, "doctor of physick," a Buckinghamshire

man, who was an Eton Scholar of King's College,

Cambridge, in I S82, B.A. I S86-7, M.D. c. I S98,

Fellow of King's, I ss S-I S99 His family had

property at Maulden, Beds. Of the rest, Michael

W elles was a Bedfordshire man, related to the Halls,

and mentioned in the will of John Hall's daughter,

Elizabeth, Lady Bernard.

The most interesting name in William's will is that

f " " " " M tth M . t o my man or my servant, a ew orrts, o

whom he leaves his books of Astronomy and Alchymy

with the hesitating condition that if his son, John,

intends to study "that art," Morris is to give him

instruction. Morris, it would seem, is employed in

William's profession as dispenser or secretary.

Whether he was at Acton in December, I 6o7, is not

clear. What is evident is that shortly afterwards he

was at Stratford with John. There, in I 6 I 3, he

married Elizabeth Rogers, and had children Susanna,

John, Elizabeth, and Matthew. The first three

names suggest intimacy with the family of Shakes-

peare's son-in-law. Furthermore, he is brought into

direct connection with Shakespeare in an indenture of

I 6 I 8, relating to the transference of Shakespeare's

house in Blackfriars to the use of Susanna Hall, to

which Matthew IVlorrys "of Stratford on Avon" is

a party.

Mr. Irvine Gray's investigation of Bedforshire

parish registers has brought to light complete evidence

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

9

of the relationship of the Hall and W elles families.

His attention has been concentrated on the two small

villages of Carlton and Chellington, near Harrold in

Bedfordshire. At a remote period the two benefices

were united, but the registers are distinct. From

I S77 to his death in I 642 the rector was Thomas

W elles, whose tombstone in Carlton church records

that he died "Aged about a Hundred." His son,

Michael, born in IS 7 8, married a daughter of William

Hall, in whose will he is proposed as executor in case

Dive and John decline to act. Michael W elles had a

son, Thomas, and in her will (1 669) Elizabeth Hall,

Lady Bernard, bequeaths so to "my cousin, Thomas

Welles of Carlton, Beds., gent." The registers of

either parish contain many entries of the W elles

family, and two inscriptions of the Carlton branch of

it occur at so distant a place as Elm, Cambs., in I 694

and I7I3. '

The Carlton register witnesses that William Hall

was resident there from I S69 to I S90. During those

years it contains the baptisms of five daughters and one

son, and burials of two daughters and two sons; also

the marriage of Elizabeth Hall to Edmund Sutton, in

August, I 590. After that date there are no Halls in

the register, and it must seem that William Hall

quitted the place. But a Carlton terrier of I 607 has

various references to "the land of Mr. Hall," which

may imply that he still owned property in the parish.

The baptisms of Dive and John are not in the Carlton

register: possibly they may be found at some neigh-

bouring village. William Hall appears in a Lay

Subsidy for Carlton in I 593, and again in I S97, but

10 SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

with a note in the latter year that he has departed. In

the early years of Edward VI, William Hall, generosus,

appears in the neighbouring parish of Turvey.

\Vhen, where, and how did Hall and Shakespeare

become first acquainted? At the Acton house, in

London, or at the New Place where Shakespeare set

up house for himself and daughters in I 597?

Unlike his brother-in-law, William Sheppard, John

took no medical degree at Cambridge. He took the

usual course in Arts, ending with M.A. in I 597, when

he was 22. In the sixteenth century continuous

residence for nine terms (three years) was required for

proceeding from B.A. to M.A., and for so long Hall

must have been at Cambridge. After that he studied

medicine, apparently at a French University, and

could scarcely be engaged in professional work much

before I 6oo.

He had no qualification for practice in Acton or

London. By the Charter of the Royal College of

Physicians it was prescribed that no person should

practise physic in London, or within seven miles of it,

unless with sanction of the President and Fellows.

Graduates in medicine of Oxford and Cambridge might

practise if they had license from the University Chan-

cellor. Graduates in medicine of foreign universities

had no authority to practise in England unless they

had licence from the bishop of the diocese. Until

Post-Reformation times episcopal registers rarely

contain any mention of licences granted, and it is

fairly evident that medical men seldom applied for

them. There is no mention of such a grant to Hall

at Worcester, and we may fairly assume that he had

- .. ~ - - ~ n j - -

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW !I

none. Why, of all places, did he choose Stratford

for a start in his career?

A possible answer to this question is supplied by the

unexpected appearance on the scene of two familiar

Stratford men-Abraham Sturley and Sir Thomas

Lucy of Charlecote.

Abraham Sturley matriculated at Cambridge at

Queens' College-the College of Dive and John Hall

-in the Easter term, I 569. Richard Sturley, who

matriculated from the same College in I 564, was

perhaps hts brother. The facts are derived from the

V niversity Grace Books, and as admissions at Queens'

College do not begin until some years later, we have

no knowledge of the county of their birth. The sur-

name--otherwise spelt Strelly-should imply that

the family was derived from Strelly, Notts. In or

before I 57 5, Mr. Fripp tells us that Abraham was in

the service of Sir Thomas Lucy in a legal capacity

and variously described as the knight's "servant" or

"retainer." His name is familiar to Shakespeare

students for his correspondence with Richard Quiney

on matters of busmess concerning Shakespeare. There

is no reason to suppose that he had family associations

with Bedfordshire, but Mr. Fripp is authority for the

fact that he visited Cambridge and Bedford early in

I 598 in behalf of sufferers from fires at Stratford. A

vtsit to Cambridge would be natural if among scholars

there he retained friends of student days: but why

Bedford?

The Lucy family-including Sir Thomas of legend-

ary fame-possessed ample estates in Bedfordshire,

and it is likely that Sturley acted as estate agent and

12 SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

rent-collector and holder of a manor court. The con-

nection of Charlecote with Bedfordshire was of old

standing and lasted far into the seventeenth century.

Several mentions of Lucy names occur in Beds. parish

registers: one is of Constance, daughter of Richard

Lucy of Charlecote, who married Sir John Burgoyne,

Bart., of Sutton, Beds. It is highly suggestive that

some of the family estates lay in Carlton parish. Here

there were two manors, one called Pabenhams, the

other Carlton and Chellington. Pabenhams passed

by marriage of a de Pabenham heiress into the posses-

sion of the Lucy family. It was alienated by Sir

Thomas (of the legend) in I 569, in which year

William Hall was clearly living at Carlton. An

Inquisitio Post Mortem in I 602 states that at that

date Lord Mordaunt was seised of the 1.\tlanor of

Carlton and Chellington together with appurtenances

and of a close called "long close" lying in Carlton,

which he purchased from William Hall. The Court

Rolls of Carlton Manor state that Sir Thomas Lucy

held his court at Carlton in 8 Henry VI and again in

the following year. In a terrier of Carlton (I 6o7)

there are several references to land of William Hall.

But in his will William makes no mention of property

there and it may be assumed that he parted with it

when he went to live at Acton.

The facts so far ascertained in the early life of John

Hall reveal far more than the Stratford Legend does of

the youth of Shakespeare. The Orthodox interpreta-

tion of the conflicting stories told a century or more

after the events has only fostered the Heretical Schools

which ascribe the authorship of the poems and plays

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW 13

to anyone rather than the Stratford man. The only

evidence of his existence is in the church register of

the baptism of his children, and it is a gratuitous

assumption that he was then resident at Stratford or

present at the ceremony. No mention of him in

municipal records or in letters of

Stratfordians serves to identify him with the dramatist.

In the documents cited in the "Lives" there is only

one which so identifies him, and the witness is Shakes-

peare in his will. The "Centurie of his Prayse,"

beginning with Meres in I 598, is continuous thmugh-

out his literary life. From first to last Stratford was

seemingly unconscious of the splendour of its Star of

Poets. In a letter of Abraham Sturley (I 5 9li ),

addressed to his neighbour, Richard Quiney, he

mentions Shakespeare as a man of substance who

may advance money in the concerns of the town, and

he passes to the topics of markets and "beeves,"

exactly as Shallow talks of fairs and "bullocks" in

connection with the Psalmist's text on the certainty

of death. The Puritan antipathy of the Corporation

to stage performances was so pronounced when

Shakespeare was at the zenith of his fame that they

refused to admit players to the town, and even paid

them to stop away. When Shakespeare died the

local folk put on the flagstone of his grave some

doggerel rimes which might have served for any

tradesman in the town. The monument and bust

were the work of a London mason, and probably were

provided by more scholarly friends at a later time.

When Shakespeare occupied the New Place in I 597

he found homely neighbours in such people as Sturley

'4

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

and Quiney, and they found in him no more than

was in themselves.

In a society so provincial and unimaginative, John

Hall, from his advent at Stratford, could not fail to

interest Shakespeare. He was young and brought

talk of recent day.; at Cambridge and in France-

almost certainly of Montpellier and its great medical

Professor, Rabelais. Probably when he started in his

profession he lodged with some Dame Quickly, and

was a constant visitor at the New Place. Perhaps he

attended Shakespeare professionally. We know that

he accompanied him on a visit to London in I6I4.

The names of Stratford patients included in Hall's

case book are interesting, but unfortunately it contains

few dates, and none earlier than I 6 I 7. It does not

include Shakespeare or any of the Lucy family of

Charlecote, but mentions "generosa" Hall, uxor mea,

and their daughter Elizabeth. Among others the

following occur:

"Eques Rainsforde," "Domina Rainsforde," and

"Mr. Drayton, poeta laureatus." These were Sir Henry

of Clifford Chambers and his wife Lady Ann, daughter

of Sir Henry Goodere of Polesworth, Warwicks, at

whose house Drayton for many years used to pass

some months in summer; she was the Idea celebrated in

Drayton's sonnets.

"Katherine" Sturley, perhaps a daughter of

Abraham.

"Generosus Nash, aet. 62," perhaps a relation of

Thomas, husband of Elizabeth Hall.

"Anna Greene, 'generosa,' jiliola primogenita Causi-

dici Greene," i.e. daughter of Thomas, a barrister of

i

t

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

the Middle Temple, in whose diary he calls Shake-

speare his "Cosen."

"Mr. Quiney," perhaps Thomas, husband of

J udith Shakespeare.

Neither in the case book nor from any Stratford

sources do we get any clue as to the date when Hall

began his residence at Stratford. Is it just possible

that in the plays there is incidental evidence to deter-

mine it? Hall was continuously resident at Cam-

bridge, where he did not study medicine, until I 597

After that year a medical course in France could

scarcely have occupied less than two or three years.

It is unlikely that he started in practise at Stratford

before I 599-I 6oo. What plays did Shakespeare

produce about that time?

From external evidence Sir E. K. Chambers in his

William Shakespeare (Vol. I, pp. 248-9) gives the

following dates: Henry 17, I 599; As You Like It, I 6oo;

Twelfth Night, I 6o2; Merry Wives, I 602.

But the first staging and composition of some of

them may be earlier; none of them are in the list of

Palladis Tamia (I598). In their theme they form a

natural group belonging to the period of Shakespeare's

shrewd and mirthful comedy. In them, and in no

earlier plays, there are some odd features of a casual

kind which suggest that Hall's fleeting talk of Cam-

bridge and France has crept into them.

Of the practice of English universities Shakespeare

seems to have had more knowledge than might be

expected of one who was not, as Hall was, a graduate

of Oxford or Cambridge. At Cambridge a graduate

was said to "proceed," when he advanced from a lower

. .. .. ~ - ' - - - -- ~ . . . . . . -

16

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

to a higher degree, and the cerem h.

admitted to the latter called at w tch he was

Remark how the three t ommencement."

Timon's speech to A erms together in

pemantus .J. tmon IV 3).

' ' .

Hadst thou like fi h

The sweet t tl' swath procudd

natudre dhid comme!lce sin

ma e t ee hard m 't.

There is evidence that Camb 'd .

mind when he made K' Lrt ge Shakespeare's

mg ear complam to Regan

'Tis not in thee-to scant my .

SIZes.

"Size" is a Cambrid e d .

food or drink priv!tel word or a certam quantity of

The word Y ?r ered from the buttery.

qmte pecuhar to Cambrid .

daughter umversities of D bl' y ge and Its

Minsheu in his Gut'd ,.,.. u m, ale and Harvard.

. e .o .1.ongues(I6I7) "I

portiOn of bread and dri k. . . t IS a

Cambridge scholars h n , It ts a farthmg which

with the letter S a . ave at the ?uttery; it is noted

halfe a farthing , ' Oxford the letter Q, for

was "battels." . "Ab e word at Oxford

. atement of stzes w C 11

pumshment alternative to " atin " a o ege

an apparent allu . L g, to whtch there is

ston In ear s next wo d "

the bolt against my corn . , r s, to oppose

I tng m.

n Merry Wives the French docto . Il .

Shakespeare is reckles . . . r ts ea ed CaiUs.

s In gtvmg nam h'

acters and regardless f d. ffi . . .es to ts char-

was the name ori i o Il I e:mg conditiOns. Oldcastle

Falstaff, and Sir ]!h Y gtven to the character of

of Sir John Fastolfen s was suggested by that

course we . . n aster Doctor Caius of

must recogmse the distinguished h . .

p ystctan,

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

John Caius, the founder of Caius College at Cam-

bridge, who died in I 573 In John Hall's student

days stories lingered in Cambridge of the violent

quarrels of the doctor with the University officials-

particularly of his vehement dislike of Sir Hugh Evans'

countrymen, whom he expressly excluded from the

benefit of his foundation. He was physician to

Edward VI, Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, just

as his namesake in the play was the court physician at

Windsor. Otherwise there is no resemblance between

the two. John Caius was not a French doctor. As an

ardent Catholic he studied medicine at the Italian

University of Padua, but John Hall at a Protestant

French University. Both John Caius and John Hall

graduated in Arts at Cambridge before they studied

medicine abroad.

When and how did Shakespeare acquire his know-

ledge of French speech such as is employed in Henry V

and Merry Wives and in no play of earlier date? His

scene in earlier plays is often in France, but the

courtiers of Navarre and the royalties of King John

speak English. For French dialogue the talk between

the French King and Helen, daughter of the physician,

Gerard de Narbon, might have given an opportunity

of which Shakespeare did not avail himself. Transla-

tions of French books were common in Tudor days,

and it is just possible that he was acquainted with an

otherwise unknown English translation of Belleforest's

Histoires Tragikes, itself a translation of an Italian

original; otherwise Shakespeare drew his comedy plots

exclusively from Italian literature. The scenes in

Henry r and Merry Wives, in which French dialogue

18 SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

occurs, are partly in English, partly in French. It is

noticeable that in Henry F, Act m, Scene 7, the

Dauphin quotes a text from the French Protestant

translation of the New Testament, a version no doubt

current at Montpellier, but not very likely to be known

to Shakespeare. One scene in Henry V.-that between

the Princess Katherine and her maid-is written

entirely in French of a fairly idiomatic kind. It must

have been "caviare to the general" of the Globe

Theatre. It is irrelevant in its place in the play, for

the Princess has no reason to learn English when the

French court was confident of victory and the English

King and people were regarded with contempt. It is

unfitting to the majestic theme of the play and an ill

introduction of the future Queen of England. Its

sole motive is to introduce an obscene jest which is

uncharacteristic of Shakespeare at his worst. If not

actually written by Hall it was introduced by some one

who was a better French linguist than dramatic artist.

So far as we can learn from the Plays there was only

one French author in whom Shakespeare was interested

-Rabelais. No English translation of Pantagruel is

known to have existed in his day, and there is small

likelihood that he had French enough to unravel the

Rabelaisian jargon which discomfited U rquhart and

even French editors. His acquaintance with Rabelais'

book is casual and general and his notes of names and

incidents seem to be drawn from conversation rather

than the written page. Something of Gargantua was

already known to Shakespeare before the date of his

first introduction to Hall. In Book I, chapter 4,

Rabelais introduces a great Sophister-Doctor, Tubal

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

Holofernes, who taught the infant Gargantua his

A.B.C. The odd combination of names suggested

the names of characters in Loves' Labours Lost and the

Merchant of Fenice, both written before I598. In the

plays written in I 599 or after I 6o2 we meet with

more conscious association with Rabelais. In As

You Like It, Rosalind wishes that she had Gargantua's

mouth. In Twelfth Night Feste delights Sir Andrew

with the Rabelaisian nonsense about Pigromitus and

the Vapians passing the equinoctial of Queubus.

Rabelais makes Queubus a personal name, translated

Lord Kiss breech by U rquhart. In the last scene of

Henry F the French King's jest about "maiden walh"

is an unpleasant reminder of ribald talk of Panurge.

In King Lear (?I 6o 5) Edgar, in his assumed madness,

says, "Nero is an angler in the lake of darkness,"

which looks like a confused recollection of what

Epistemon says of his vision of the occupations in

after life of historical celebrities, "Trajan was a fisher

of frogs, Nero a base blind fiddler."

All these four plays were written about the years

when John Hall made acquaintance with Shakespeare

at the New Place. He was young and brought fresh

reminiscences of Montpellier and of the tutelary

genius of its University, Rabelais, student and doctor

of medicine there, whose red gown was used to invest

students there on taking a degree; his first two books,

printed in I 54 7, would be in the hands of the scholars,

and it is likely that Hall brought the volume to

Stratford, and gave Shakespeare the benefit of his

translation.

Of course the connection of John Hall with the

.. - - - - ~ ~ ~ . . '" .... _ " - - - - - - - - - - ~ - - - ~ - ~ I- '

- ' ~ " .... c -- "

:!0 SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

Plays is matter of surmise, but surmise based on

ascertained and dated facts. The Stratford School

does not approve of surmise unless it is based on the

gossip of the nameless and ignorant gobes-mouches of

Stratford whose grandfathers had buried the poet in

their church. Once again, and not too often, it must

be said that no Stratford document can prove that

Shakespeare was continuously resident in the town

before his retirement in I 597, when half his literary

life was done. If he was, as on good evidence we

are told, "a schoolmaster in the country," it is likely

that he was not present at the baptisms of his children.

Population in Elizabethan days was much more

mobile than is conceived by Stratford enthusiasts. In

a book, A Chapter in the Early Life of Shakespeare,

printed in I926, I developed a theory that Shakespeare

was brought up at Polesworth, in North Warwicks.

In that neighbourhood he mentions many towns and

villages in the plays, one actually in Polesworth parish,

which in some verses of I 6 53 is identified with the

scene of Christopher Sly's tippling, but he never

mentions Stratford or any place near it. Sir E. K.

Chambers in his William Shakespeare dismisses my

theory as "most improbable," since Polesworth is

too far from Stratford. Since I wrote that book I

have discovered a remarkable entry in the P;lesworth

register of the baptism on July 5, I632, of Susanna,

daughter of "Mr" Quiny. The Quiny family were

all resident at Stratford, and there is no other mention

of the name at Polesworth. What brought him to a

place so distant? Apparently he is Thomas, the

unthrifty husband of Judith Shakespeare. In I632

SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW 21

he was in financial straits and, as there was a likelihood

that he would part with his house in Stratford, John

Hall and Thomas Nash, husband of Shakespeare's

grand-daughter, Elizabeth, in the interest of Judith

took over the lease of the house. Was Susanna

Quiny Shakespeare's grand-daughter? Nothing

further is known of her. If-which is doubtful-

Mr. Quiny journeyed from Stratford to Polesworth

for the christening of his daughter is it altogether im-

probable that for the baptism of his children Shakes-

peare travelled from Polesworth, or some other

Warwickshire place, to Stratford? Thrice in their

correspondence of I 598 Sturley and Quiny speak of

Shakespeare as their "countryman," inasmuch as they

associated him with the "county" of Warwick rather

than with Stratford. This tallies with William

Beeston's statement that in his younger days Shakes-

peare had been a schoolmaster in the" country." There

were many good schools in Warwickshire, but I have

grave doubts that the apprentice who, according to the

Legend, left Stratford School at the age of thirteen,

had poor qualifications as a teacher-or even as a

writer ot plays.

In his William Shakespeare Sir E. K. Chambers

devotes a long section to what he calls the Shakespeare

Mythos, in which he includes the gossip of Stratford

of a time when "the inquisitiveness of tourists was

beginning to meet with the natural response of local

guides." Sir E. K. Chambers objects that my theory

had "no support from records or probability." Of

the improbability of the Legendary stories my book

gave, I think, ample evidence. Of record there is

:Z2 SHAKESPEARE'S SON-IN-LAW

none at Stratford. Of course, Polesworth has no

municipal records, and its church register only begins

in r 6 3 r. Stratford in its corporation documents has

minute evidence of the lives and conditions of its

inhabitants, and its church register covers the whole

period of Shakespeare's life. Neither source affords

a particle of information about the man who was a

dramatist and also the richest man in the town.

Admitting his doubt of the credibility of most of the

articles of the geocentric Stratford faith, Sir E. K.

Chambers yet believes that authority must be attached

to the testimony of certain writers of the late seven-

teenth and early eighteenth century that traditions,

e.g. of the deer-stealing business, survived in their days

at Stratford, and he does not welcome the suggestion

that the whole of the authoritarian belief is unbelievable.

When I am confronted with the caricature portrait of

young Shakespeare, drawn by Stratford artists, I must

express my concurrence with the justice of the verdict

of Mrs. Betsy Prig about a similar figment-"! don't

believe there was no sich a person."

Вам также может понравиться

- Pickett’s Charge, July 3 and Beyond, Omnibus E-book: Includes Pickett’s Charge—The Last Attack at Gettysburg by Earl J. Hess and Pickett’s Charge in History and Memory by Carol ReardonОт EverandPickett’s Charge, July 3 and Beyond, Omnibus E-book: Includes Pickett’s Charge—The Last Attack at Gettysburg by Earl J. Hess and Pickett’s Charge in History and Memory by Carol ReardonОценок пока нет

- Carlo GINZBURG. High and Low - The Theme of Forbidden Knowledge in The Sixteenth and Seventeenth CenturiesДокумент23 страницыCarlo GINZBURG. High and Low - The Theme of Forbidden Knowledge in The Sixteenth and Seventeenth CenturiescirolourencoОценок пока нет

- Postman Always Rings Twice - Sian RuffellДокумент2 страницыPostman Always Rings Twice - Sian Ruffellsianr97Оценок пока нет

- Microhistory Robisheaux FFДокумент6 страницMicrohistory Robisheaux FFdiegopratsОценок пока нет

- Norman Malcolm-Thoughtless BrutesДокумент17 страницNorman Malcolm-Thoughtless BrutesB Ochoa100% (1)

- 15.polychronic Knowledge of Health and Healthcare and Polythetic Culture A DiachronicДокумент16 страниц15.polychronic Knowledge of Health and Healthcare and Polythetic Culture A Diachroniclaura isabellaОценок пока нет

- Munday Microhistory 2014Документ18 страницMunday Microhistory 2014Baagii BataaОценок пока нет

- Tracking Medicine - John E. WennbergДокумент340 страницTracking Medicine - John E. WennbergurbanincultureОценок пока нет

- Bio of Edward Kelly by Michael WildingДокумент28 страницBio of Edward Kelly by Michael WildingTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Postmortem Skeletal LesionsДокумент11 страницPostmortem Skeletal LesionsJelena WehrОценок пока нет

- Micro Analysis and The Construction of The SocialДокумент12 страницMicro Analysis and The Construction of The Sociallegarces23Оценок пока нет

- John Rennie Short - CV - PDFДокумент57 страницJohn Rennie Short - CV - PDFDavid del MaderoОценок пока нет

- Critical Studies in Media CommunicationДокумент23 страницыCritical Studies in Media CommunicationAneelaОценок пока нет

- PatientsAndPractitioners PDFДокумент362 страницыPatientsAndPractitioners PDFTeodor MogoșОценок пока нет

- Living The Long Life Physical and SpiriДокумент34 страницыLiving The Long Life Physical and SpiriBeni ValdesОценок пока нет

- 2019 Bioarchaeology and Social Schrader - Activity, Diet and SocialДокумент221 страница2019 Bioarchaeology and Social Schrader - Activity, Diet and Socialc.noseОценок пока нет

- John Dee and The Quest For A British Emp PDFДокумент11 страницJohn Dee and The Quest For A British Emp PDFrdenadai_silvaОценок пока нет

- Racism and The Aesthetic of Hyperreal Violence (Giroux 1995)Документ19 страницRacism and The Aesthetic of Hyperreal Violence (Giroux 1995)William J GreenbergОценок пока нет

- LOCK Anthropology of Bodily Practice and KnowledgeДокумент23 страницыLOCK Anthropology of Bodily Practice and KnowledgebernardodelvientoОценок пока нет

- Thoughts John DeeДокумент353 страницыThoughts John DeeJ. Perry Stonne100% (1)

- Soc 362 Final PaperДокумент9 страницSoc 362 Final PaperDerek KingОценок пока нет

- Microhistory and The Histories of Everyday Life: Cultural and Social HistoryДокумент24 страницыMicrohistory and The Histories of Everyday Life: Cultural and Social HistoryfiraОценок пока нет

- Paracelsus, and 500years Ofencouraging Scientific InquiryДокумент2 страницыParacelsus, and 500years Ofencouraging Scientific Inquiryjasper_gregory100% (1)

- AJA - The Social Archaeology of Funerary RemainsДокумент2 страницыAJA - The Social Archaeology of Funerary RemainsDuke AlexandruОценок пока нет

- Get Out (February 2017) - AnalysisДокумент3 страницыGet Out (February 2017) - AnalysisNathan CollinsОценок пока нет

- Crash Film AnalysisДокумент4 страницыCrash Film AnalysisstОценок пока нет

- Garner, Aubry Accepted Thesis 5-23-16Документ105 страницGarner, Aubry Accepted Thesis 5-23-16Ian GeikeОценок пока нет

- Henrik Ibsen and Conspiracy Thinking - The Case of Peer GyntДокумент36 страницHenrik Ibsen and Conspiracy Thinking - The Case of Peer GyntAyla BayramОценок пока нет

- Superbad Mise en Scene 3Документ4 страницыSuperbad Mise en Scene 3api-297666683Оценок пока нет

- The Paracelsian Compromise in Elizabethan EnglandДокумент29 страницThe Paracelsian Compromise in Elizabethan Englandsalah64Оценок пока нет

- Bronislaw MalinowskiДокумент15 страницBronislaw MalinowskimorikolulaОценок пока нет

- Crash and The Real Collision With Modern Rasist America: Zofotă 1Документ6 страницCrash and The Real Collision With Modern Rasist America: Zofotă 1Andreea Zofotă100% (1)

- Forest Gump DeconstructionДокумент4 страницыForest Gump DeconstructionCallumKopkoОценок пока нет

- Macrohistory vs. MicrohistoryДокумент4 страницыMacrohistory vs. MicrohistoryaksoyraОценок пока нет

- Renaissance EnlightenmentДокумент94 страницыRenaissance EnlightenmentAhmad Makhlouf100% (1)

- Giovanni Levi. Biography and MicrohistoryДокумент3 страницыGiovanni Levi. Biography and MicrohistoryAndré Luís Mattedi DiasОценок пока нет

- The Study of Christian Cabala in English: Don KarrДокумент92 страницыThe Study of Christian Cabala in English: Don KarrAnonymous HtDbszqtОценок пока нет

- Do The Right ThingДокумент4 страницыDo The Right Thingapi-548749586Оценок пока нет

- Smallpox Vaccines, Historical Review PDFДокумент9 страницSmallpox Vaccines, Historical Review PDFVijaykiran ReddyОценок пока нет

- Hughey.2009.Cinethetic RacismДокумент35 страницHughey.2009.Cinethetic RacismPeter FredricksОценок пока нет

- Joyce E. Chaplin Natural Philosophy and An Early Racial Idiom in North America Comparing English and Indian Bodies LEIDOДокумент25 страницJoyce E. Chaplin Natural Philosophy and An Early Racial Idiom in North America Comparing English and Indian Bodies LEIDOVanessa MontenegroОценок пока нет

- The Search For Ancient Wisdom in Early Modern Europe: Reuchlin and The Late Ancient Esoteric ParadigmДокумент19 страницThe Search For Ancient Wisdom in Early Modern Europe: Reuchlin and The Late Ancient Esoteric ParadigmNițceValiОценок пока нет

- Andreatta2014 Subverting Patronage in Translation Flavius Mithridates, Giovanni Pico Della Mirandola, and Gersonides' Commentary On The Song of SongsДокумент34 страницыAndreatta2014 Subverting Patronage in Translation Flavius Mithridates, Giovanni Pico Della Mirandola, and Gersonides' Commentary On The Song of SongsRoberti Grossetestis Lector100% (2)

- Rafał Prinke, Heliocantharus BorealisДокумент38 страницRafał Prinke, Heliocantharus Borealisbalthasar777100% (1)

- (The Eddington Memorial Lectures, Cambridge University) Charles Webster-From Paracelsus To Newton - Magic and The Making of Modern Science-Cambridge University Press (1983)Документ59 страниц(The Eddington Memorial Lectures, Cambridge University) Charles Webster-From Paracelsus To Newton - Magic and The Making of Modern Science-Cambridge University Press (1983)zC6MuNiWОценок пока нет

- John Dee - Hieroglyphic MonadДокумент47 страницJohn Dee - Hieroglyphic MonadErik KapferОценок пока нет

- The Alchemical Patronage of Sir William Cecil, Lord BurghleyДокумент180 страницThe Alchemical Patronage of Sir William Cecil, Lord BurghleyJames CampbellОценок пока нет

- Monica GreenДокумент41 страницаMonica GreenElis FalasquiОценок пока нет

- Notes For Woman WangДокумент4 страницыNotes For Woman WangAlexSpeiserОценок пока нет

- Satire As Medicine in Restoration and Early Enlightment CenturyДокумент24 страницыSatire As Medicine in Restoration and Early Enlightment CenturyGustavo Ramos de SouzaОценок пока нет

- The Apocalyptic Eucharist and Religious Dissidence in Stefan Michelspacher's Cabala - Spiegel Der Kunst Und Natur, in Alchymia (1616) PDFДокумент25 страницThe Apocalyptic Eucharist and Religious Dissidence in Stefan Michelspacher's Cabala - Spiegel Der Kunst Und Natur, in Alchymia (1616) PDFVanniОценок пока нет

- Gerald A. Press. The Development of The Idea of History in AntiquityДокумент185 страницGerald A. Press. The Development of The Idea of History in AntiquityAndrey TashchianОценок пока нет

- Death MaskДокумент4 страницыDeath MasktanitartОценок пока нет

- Alchemy in Early Modern EnglandДокумент5 страницAlchemy in Early Modern EnglandHugo Bohorquez PeñaОценок пока нет

- Volumen Medicinae Paramirum ParacelsusДокумент39 страницVolumen Medicinae Paramirum ParacelsusAlinda Nagy100% (2)

- English literary afterlives: Greene, Sidney, Donne and the evolution of posthumous fameОт EverandEnglish literary afterlives: Greene, Sidney, Donne and the evolution of posthumous fameОценок пока нет

- Medical Humanity and Inhumanity in the German-Speaking WorldОт EverandMedical Humanity and Inhumanity in the German-Speaking WorldОценок пока нет

- The Discovery of a World in the Moone Or, A Discovrse Tending To Prove That 'Tis Probable There May Be Another Habitable World In That PlanetОт EverandThe Discovery of a World in the Moone Or, A Discovrse Tending To Prove That 'Tis Probable There May Be Another Habitable World In That PlanetОценок пока нет

- Amye Robsart and The Earl of Leycester OptДокумент377 страницAmye Robsart and The Earl of Leycester OptTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Roydon Lodge - A Manor House Through Four Centuries by A.R. CookДокумент123 страницыRoydon Lodge - A Manor House Through Four Centuries by A.R. CookTerryandAlan100% (1)

- Annals of Medical History III Reduced SizeДокумент438 страницAnnals of Medical History III Reduced SizeTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Annals of Medical History IV Reduced SizeДокумент437 страницAnnals of Medical History IV Reduced SizeTerryandAlan100% (1)

- F - Rabelais - À - La - Faculté - de - Médicine Reduced SizeДокумент83 страницыF - Rabelais - À - La - Faculté - de - Médicine Reduced SizeTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- The Forest of Arden by George Wharton (1914)Документ230 страницThe Forest of Arden by George Wharton (1914)TerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- The Metrical Dindshenchas Vol 4 Edited by Edward Gwynn (1906)Документ114 страницThe Metrical Dindshenchas Vol 4 Edited by Edward Gwynn (1906)TerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Whitney S Choice of EmblemesДокумент628 страницWhitney S Choice of EmblemesTerryandAlan0% (1)

- Annals of Medical History II Reduced SizeДокумент439 страницAnnals of Medical History II Reduced SizeTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Bio of Edward Kelly by Michael WildingДокумент28 страницBio of Edward Kelly by Michael WildingTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Relationship of Celtic Ogmios and Hercules - HeraklesДокумент4 страницыRelationship of Celtic Ogmios and Hercules - HeraklesTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Stair Ercuil Ocus A Bas - The Life and Death of Hercules - Edited and Translated by Gordon Quin (1936)Документ312 страницStair Ercuil Ocus A Bas - The Life and Death of Hercules - Edited and Translated by Gordon Quin (1936)TerryandAlan100% (1)

- Annals of Medical History I Reduced SizeДокумент480 страницAnnals of Medical History I Reduced SizeTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Occult Science in Medicine by Franz HartmanДокумент107 страницOccult Science in Medicine by Franz HartmanTerryandAlan100% (2)

- Irish NenniusДокумент470 страницIrish NenniusTerryandAlan100% (2)

- An Exact Collection of The Choicest and More Rare Experiments and Secrets in Physick and Chyrurgery (Both Cymick and Galenick)Документ496 страницAn Exact Collection of The Choicest and More Rare Experiments and Secrets in Physick and Chyrurgery (Both Cymick and Galenick)TerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- The Metrical Dindshenchas Vol 2 Edited by Edward Gwynn (1906)Документ486 страницThe Metrical Dindshenchas Vol 2 Edited by Edward Gwynn (1906)TerryandAlan100% (2)

- The Anatomy of MelancholyДокумент533 страницыThe Anatomy of MelancholyTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Remaines of Gentilisme and Judaisme 1686Документ282 страницыRemaines of Gentilisme and Judaisme 1686TerryandAlan100% (1)

- The Life and Times of Anthony WoodДокумент373 страницыThe Life and Times of Anthony WoodTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- The Works of Fulke GrevilleДокумент60 страницThe Works of Fulke GrevilleTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Symbolae Ad Herculis Historiam Fabularem Ex Vasculis Pictis Pititae by Josephus Boehm (1909)Документ51 страницаSymbolae Ad Herculis Historiam Fabularem Ex Vasculis Pictis Pititae by Josephus Boehm (1909)TerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- The Metrical Dinshenchas Vol 2 Edited by Edward Gwynn (1906)Документ124 страницыThe Metrical Dinshenchas Vol 2 Edited by Edward Gwynn (1906)TerryandAlan50% (2)

- Gargantua and PantagruelДокумент420 страницGargantua and PantagruelTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- The Anatomy of MelancholyДокумент533 страницыThe Anatomy of MelancholyTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Fasciculus Chemicus or Chemical Collections and The Arcanum or Grand Secret of Hermetic Philosophy by Arthur Dee (1650)Документ328 страницFasciculus Chemicus or Chemical Collections and The Arcanum or Grand Secret of Hermetic Philosophy by Arthur Dee (1650)TerryandAlan100% (3)

- Law Sports at Gray's Inn 1594 (1594) Including Those by ShakespeareДокумент383 страницыLaw Sports at Gray's Inn 1594 (1594) Including Those by ShakespeareTerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Herakles by George Cabot Lodge (1908)Документ294 страницыHerakles by George Cabot Lodge (1908)TerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Hercules PiochymicusДокумент218 страницHercules PiochymicusincoldhellinthicketОценок пока нет

- Hercules Furens A Tragedy by Seneca Edited by Charles Beck (1845)Документ122 страницыHercules Furens A Tragedy by Seneca Edited by Charles Beck (1845)TerryandAlanОценок пока нет

- Kwabena Donkor: Biblical Research InstituteДокумент30 страницKwabena Donkor: Biblical Research InstitutePatricio José Salinas CamposОценок пока нет

- FILIPINO VALUES FinalДокумент126 страницFILIPINO VALUES FinalJoe Genduso87% (15)

- Soren Kierkegaard Historical and Intellctual Mileu (The Context)Документ24 страницыSoren Kierkegaard Historical and Intellctual Mileu (The Context)Mark ZisterОценок пока нет

- Plant As ShaykhДокумент7 страницPlant As Shaykhgourdgardener100% (2)

- Eclectroal Reforms in India - Election LawДокумент20 страницEclectroal Reforms in India - Election LawNandini TarwayОценок пока нет

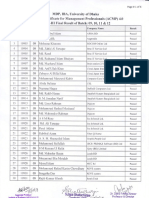

- ACMP4.0 Phase-III ResultДокумент6 страницACMP4.0 Phase-III ResultasmreazОценок пока нет

- Receptive Ecumenism and The Call To Catholic Learning - Exploring A Way For Contemporary Ecumenism (2008, Oxford University Press, USA)Документ571 страницаReceptive Ecumenism and The Call To Catholic Learning - Exploring A Way For Contemporary Ecumenism (2008, Oxford University Press, USA)abel67% (3)

- Muslim Girl Names - Girl Names From The Quran - 2175 Muslim Names - Page 3Документ5 страницMuslim Girl Names - Girl Names From The Quran - 2175 Muslim Names - Page 3Nadir IqbalОценок пока нет

- Marcel Detienne - Dionysos Slain-The Johns Hopkins University Press (1979)Документ143 страницыMarcel Detienne - Dionysos Slain-The Johns Hopkins University Press (1979)lynnsimhaserfatyhakimОценок пока нет

- Kattavakkam RouteДокумент2 страницыKattavakkam RouteSundarОценок пока нет

- What English Composition I Has Done For MeДокумент5 страницWhat English Composition I Has Done For Meapi-242081653Оценок пока нет

- Islamic Way of LifeДокумент36 страницIslamic Way of Lifeobl97100% (2)

- Issue of Kissing ThumbsДокумент25 страницIssue of Kissing ThumbsThe OKARVI'SОценок пока нет

- Dada GAVANDДокумент37 страницDada GAVAND2010SUNDAY100% (1)

- Right To Privacy in India PDFДокумент12 страницRight To Privacy in India PDFManwinder Singh GillОценок пока нет

- The Biblical Givers: Lesson 04: ABRAHAMДокумент2 страницыThe Biblical Givers: Lesson 04: ABRAHAMKim OliciaОценок пока нет

- Sample Essays PteДокумент6 страницSample Essays PteFatima JabeenОценок пока нет

- Somalata (Research Paper)Документ5 страницSomalata (Research Paper)ringboltОценок пока нет

- V Scott Oconnor Mdy and Other Citis of The Past in BurmaДокумент494 страницыV Scott Oconnor Mdy and Other Citis of The Past in BurmaSawОценок пока нет

- Riordan, Rick - The Kane Chronicles Survival Guide (Disney Book Group)Документ145 страницRiordan, Rick - The Kane Chronicles Survival Guide (Disney Book Group)HalJ33% (3)

- The Elephant in The Room Part 2Документ33 страницыThe Elephant in The Room Part 2Faheem Lea100% (1)

- No. Module Learning Outcomes Essential Topics Essential Skills Essential Attitudes Online Strategies Online Assessment E-Learning MaterialДокумент10 страницNo. Module Learning Outcomes Essential Topics Essential Skills Essential Attitudes Online Strategies Online Assessment E-Learning MaterialAlaissa Jazzy C. TimosanОценок пока нет

- 108 KrishnaДокумент6 страниц108 KrishnaDilip Kumar VigneshОценок пока нет

- 'Materia Ex Qua' and 'Materia Circa Quam' in AquinasДокумент14 страниц'Materia Ex Qua' and 'Materia Circa Quam' in AquinasRoberto SantosОценок пока нет

- Al GhazaliДокумент4 страницыAl GhazaliIsmail BarakzaiОценок пока нет

- Pre-Islamic Arab QueensДокумент23 страницыPre-Islamic Arab QueensNefzawi99Оценок пока нет

- Text of Muhammad Asad's Interview With Karl Gunter SimonДокумент12 страницText of Muhammad Asad's Interview With Karl Gunter SimonSmartyFoxОценок пока нет

- International Journal of English and EducationДокумент15 страницInternational Journal of English and EducationMouna Ben GhanemОценок пока нет

- Hyde QuotesДокумент1 страницаHyde QuotesSuleman WarsiОценок пока нет

- When Life Throws You A CurveДокумент168 страницWhen Life Throws You A CurveAlfreo Wilson FinnОценок пока нет