Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Keats Letters

Загружено:

ellen20Исходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Keats Letters

Загружено:

ellen20Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

JOHN KEATS LETTERS

To Richard Woodhouse

October 27th, 1818 My dear Woodhouse, Your Letter gave me a great satisfaction; more on account of its friendliness, than any relish of that matter in it which is accounted so acceptable in the 'genus irritabile'. The best answer I can give you is in a clerk-like manner to make some observations on two princple points, which seem to point like indices into the midst of the whole pro and con, about genius, and views and achievements and ambition and cetera. 1st. As to the poetical Character itself (I mean that sort of which, if I am any thing, I am a Member; that sort distinguished from the wordsworthian or egotistical sublime; which is a thing per se and stands alone) it is not itself - it has no self - it is every thing and nothing - It has no character - it enjoys light and shade; it lives in gusto, be it foul or fair, high or low, rich or poor, mean or elevated - It has as much delight in conceiving an Iago as an Imogen. What shocks the virtuous philosopher, delights the camelion Poet. It does no harm from its relish of the dark side of things any more than from its taste for the bright one; because they both end in speculation. A Poet is the most unpoetical of any thing in existence; because he has no Identity - he is continually in for - and filling some other Body - The Sun, the Moon, the Sea and Men and Women who are creatures of impulse are poetical and have about them an unchangeable attribute - the poet has none; no identity - he is certainly the most unpoetical of all God's Creatures. If then he has no self, and if I am a Poet, where is the Wonder that I should say I would write no more? Might I not at that very instant have been cogitating on the Characters of Saturn and Ops? It is a wretched thing to confess; but is a very fact that not one word I ever utter can be taken for granted as an opinion growing out of my identical nature - how can it, when I have no nature? When I am in a room with People if I ever am free from speculating on creations of my own brain, then not myself goes home to myself: but the identity of every one in the room begins so to press upon me that I am in a very

little time annihilated - not only among Men; it would be the same in a Nursery of children: I know not whether I make myself wholly understood: I hope enough so to let you see that no despondence is to be placed on what I said that day. In the second place I will speak of my views, and of the life I purpose to myself. I am ambitious of doing the world some good: if I should be spared that may be the work of maturer years - in the interval I will assay to reach to as high a summit in Poetry as the nerve bestowed upon me will suffer. The faint conceptions I have of Poems to come brings the blood frequently into my forehead. All I hope is that I may not lose all interest in human affairs - that the solitary indifference I feel for applause even from the finest Spirits, will not blunt any acuteness of vision I may have. I do not think it will - I feel assured I should write from the mere yearning and fondness I have for the Beautiful even if my night's labours should be burnt every morning, and no eye ever shine upon them. But even now I am perhaps not speaking from myself: but from some character in whose soul I now live. I am sure however that this next sentence is from myself. I feel your anxiety, good opinion and friendliness in the highest degree, and am Your's most sincerely John Keats

To George and Georgiana Keats

["The Vale of Soul-Making"] Sunday 14 Feb.-Monday 3 May 1819. Sunday Morn Feby 14th MY DEAR BROTHER & SISTER[]Call the world if you Please "The vale of Soul-making". Then you will find out the use of the world (I am speaking now in the highest terms for human nature admitting it to be immortal which I will here take for granted for the purpose of showing a thought which has struck me concerning it) I say 'Soul making' Soul as distinguished from an Intelligence- There may be intelligences or sparks of the divinity in millions-but they are not Souls till they acquire identities, till each one is personally itself. I[n]telligences are atoms of perception-they know and they see and they are pure, in short they are GodHow then are Souls to be made? How then arc these sparks which are God to have identity given them-so as ever to possess a bliss peculiar to each one's individual existence? I- low, but by the medium of a world like this? This point I sincerely wish to consider because 'I think it a grander system of salvation than the chrystiain religion -or

rather it is a system of Spirit-creation-This is effected by three grand materials acting the one upon the other for a series of years. These three Materials are the Intelligence-the human heart (as distinguished from intelligence or Mind) and the World or Elemental space suited for the proper action of Mind and Heart on each other for the purpose of forming the Soul or Intelligence destined to possess the sense of Identity. I can scarcely express what I but dimly perceive-and yet I think I perceive it-that you may judge the more clearly I will put it in the most homely form possible-I will call the world a School instituted for the purpose of teaching little children to read-I will call the human heart the horn Book used in that School-and I will call the Child able to -read, the Soul made from that School and its hornbook. Do you not see how necessary a World of Pains and troubles is to school an Intelligence and make it a Soul? A Place where the heart must feel and suffer in a thousand diverse ways! Not merely is the Heart a Hornbook, It is the Minds Bible, it is the Minds expe rience, it is the teat from which the Mind or intelligence sucks its identity. As various as the Lives of Men are-so various become their Souls, and thus does God make individual beings, Souls, Identical Souls of the Sparks of his own essence-This appears to me a faint sketch of a system of Salvation which does not affront our reason and humanity-I am convinced that many difficulties which Christians labour under would vanish before it-there is one which even now Strikes me-the Salvation of Children-In them the Spark or intelligence returns to God without any identity-it having had no time to learn of and be altered by the heart-or seat of the human Passions-It is pretty generally suspected that the cbr[i]stian scheme has been coppied from the ancient persian and greek Philosophers. Why may they not have made this simple thing even more simple for common apprehension by introducing Mediators and Personages in the same manner as in the he[a]then mythology abstractions are personified-Seriously I think it probable that this System of Soul-making-may have been the Parent of all the more palpable and personal Schemes of Redemption, among the Zoroastrians the Christians and the Hindoos. For as one part of the human species must have their carved Jupiter; so another part must have the palpable and named Mediator and Saviour, their Christ their Oromanes and their Vishnu-If what I have said should not be plain enough, as I fear it may not be, I will but [for put] you in the place where I began in this series of thoughts-I mean, I began by seeing how man was formed by circumstances-and what are circumstances?-but touchstones of his heart-? and what are touchstones? but proovings of his heart? and what are proovings of his heart but fortifiers or alterers of his nature? and what is his altered nature but his Soul?-and what was his Soul before it came into the world and had these provings and alterations and perfectionings?-An intelligence-without Identity-and how is this Identity to be made? Through the medium of the Heart? And how is the heart to become this Medium but in a world of Circumstances? . . . Your ever affectionate brother, John Keats.

To Percy Bysshe Shelley

16 August 1820 Hampstead August 16th My dear Shelley, I am very much gratified that you, in a foreign country, and with a mind almost over occupied, should write to me in the strain of the Letter beside me. If I do not take advantage of your invitation it will be prevented by a circumstance I have very much at heart to prophesy - There is no doubt that an english winter would put an end to me, and do so in a lingering hateful manner, therefore I must either voyage or journey to Italy as a soldier marches up to a battery. My nerves at present are the worst part of me, yet they feel soothed when I think that come what extreme may, I shall not be destined to remain in one spot long enough to take a hatred of any four particular bed-posts. I am glad you take any pleasure in my poor Poem; - which I would willingly take the trouble to unwrite, if possible, did I care so much as I have done about Reputation. I received a copy of the Cenci, as from yourself from Hunt. There is only one part of it I am judge of; the Poetry, and dramatic effect, which by many spirits nowadays is considered the mammon. A modern work it is said must have a purpose, which may be the God - an artist must serve Mammon - he must have "self concentration" selfishness perhaps. You I am sure will forgive me for sincerely remarking that you might curb your magnanimity and be more of an artist, and 'load every rift' of your subject with ore. The thought of such discipline must fall like cold chains upon you, who perhaps never sat with your wings furl'd for six Months together. And is not this extraordina[r]y talk for the writer of Endymion? whose mind was like a pack of scattered cards - I am pick'd up and sorted to a pip. My Imagination is a Monastry and I am its Monk - you must explain my metap [for metaphysics] to yourself. I am in expectation of Prometheus every day. Could I have my own wish for its interest effected you would have it still in manuscript - or be but now putting an end to the second act. I remember you advising me not to publish my first-blights, on Hampstead heath - I am returning advice upon your hands. Most of the Poems in the volume I send you have been written above two years, and would never have been publish'd but from a hope of gain; so you see I am inclined enough to take your advice now. I must exp[r]ess once more my deep sense of your kindness, adding my sincere thanks and respects for Mrs Shelley. In the hope of soon seeing you (I) remain most sincerely yours, John Keats

Вам также может понравиться

- The Odes of John Keats - Complete Collection: Ode on a Grecian Urn, Ode to a Nightingale, Hyperion, Endymion, The Eve of St. Agnes, Ode to PsycheОт EverandThe Odes of John Keats - Complete Collection: Ode on a Grecian Urn, Ode to a Nightingale, Hyperion, Endymion, The Eve of St. Agnes, Ode to PsycheОценок пока нет

- Passage To IndiaДокумент14 страницPassage To IndiaUma Devi100% (1)

- Rabindranath Tagore's The Wife's Letter: A Story Reveals Patriarchal DominationДокумент4 страницыRabindranath Tagore's The Wife's Letter: A Story Reveals Patriarchal DominationManoj JanaОценок пока нет

- Purloined Letter - SummaryДокумент5 страницPurloined Letter - SummaryXieanne Soriano Ramos100% (1)

- Paradise LostДокумент6 страницParadise Lostrizalstarz100% (3)

- Home Burial: by Robert FrostДокумент12 страницHome Burial: by Robert Frostjosefina100% (1)

- A Grammarian's Funeral Lect 21Документ23 страницыA Grammarian's Funeral Lect 21saad mushtaqОценок пока нет

- Faerie Queen NotesДокумент8 страницFaerie Queen NotesMohsin MirzaОценок пока нет

- PoetryДокумент5 страницPoetryIrfan SahitoОценок пока нет

- Paradise Lost Essay PDFДокумент5 страницParadise Lost Essay PDFapi-266588958Оценок пока нет

- Red Oleanders-1Документ13 страницRed Oleanders-1Khushaliba JadejaОценок пока нет

- Church Going - Philip LarkinДокумент6 страницChurch Going - Philip LarkinThe True NoobОценок пока нет

- Lycidas QuotesДокумент4 страницыLycidas QuotesSohailRanaОценок пока нет

- The Purloined LetterДокумент7 страницThe Purloined LetterHazel Ann Prado Togonon100% (1)

- Emancipation of Women in Tagore's The Wife's Letter: Dr. Sresha Yadav Nee GhoshДокумент4 страницыEmancipation of Women in Tagore's The Wife's Letter: Dr. Sresha Yadav Nee GhoshSajal DasОценок пока нет

- Emerson's "The Snow-Storm": A Representation of Natural BeautyДокумент6 страницEmerson's "The Snow-Storm": A Representation of Natural BeautyMustafa A. Al-HameedawiОценок пока нет

- Autobiographical Elements in Charles Dickens' David CopperfieldДокумент4 страницыAutobiographical Elements in Charles Dickens' David CopperfieldAnil SehrawatОценок пока нет

- In Memoriam3443Документ6 страницIn Memoriam3443Ton TonОценок пока нет

- Locksley HallДокумент7 страницLocksley HallKhadija Shapna100% (1)

- Article On Maha Swethadevi Breast GiverДокумент16 страницArticle On Maha Swethadevi Breast GiverKirran Khumar GollaОценок пока нет

- Appreciation John Donne Good Friday 1613Документ3 страницыAppreciation John Donne Good Friday 1613Rulas Macmosqueira100% (1)

- Tess'Документ4 страницыTess'Shirin AfrozОценок пока нет

- 08 - Chapter IIДокумент35 страниц08 - Chapter IINIRMAL SINGHОценок пока нет

- Vi Desse LieДокумент4 страницыVi Desse LieRahul KumarОценок пока нет

- Translation StudiesДокумент10 страницTranslation StudiescybombОценок пока нет

- Curse For A NationДокумент18 страницCurse For A NationsambidhasudhaОценок пока нет

- Epistolary in Pamela@ SHДокумент3 страницыEpistolary in Pamela@ SHShahnawaz HussainОценок пока нет

- ENGL 3312 Middlemarch - Notes Part IДокумент4 страницыENGL 3312 Middlemarch - Notes Part IMorgan TG100% (1)

- Epic Simile IsДокумент2 страницыEpic Simile IsNishant SaumyaОценок пока нет

- Journey of Maggi in Religious PoemДокумент42 страницыJourney of Maggi in Religious PoemSubodh SonawaneОценок пока нет

- Sunday Morning: by Wallace StevensДокумент4 страницыSunday Morning: by Wallace StevensMarinela CojocariuОценок пока нет

- William Wordsworth: The Manifesto of English RomanticismДокумент4 страницыWilliam Wordsworth: The Manifesto of English RomanticismVincenzo Di GioiaОценок пока нет

- Church GoingДокумент7 страницChurch GoingHaroon AslamОценок пока нет

- Individuality in Robinson Cruseo by Daneil DefeoДокумент4 страницыIndividuality in Robinson Cruseo by Daneil DefeoSafi UllahОценок пока нет

- Unit Charles Lamb: Dissertation Upon Roast Pig": 24.0 ObjectivesДокумент19 страницUnit Charles Lamb: Dissertation Upon Roast Pig": 24.0 Objectivesranjan_kr125Оценок пока нет

- Hard Times As A Dickensian DystopiaДокумент9 страницHard Times As A Dickensian DystopianaalumthendralОценок пока нет

- Themes Motifs in HamletДокумент3 страницыThemes Motifs in HamletAnjali RayОценок пока нет

- John Donne As A Religious PoetДокумент5 страницJohn Donne As A Religious Poetabc defОценок пока нет

- Robert Browning PoetryДокумент4 страницыRobert Browning PoetrypelinОценок пока нет

- The Paradox of Lightness As Heaviness of BeingДокумент5 страницThe Paradox of Lightness As Heaviness of BeingGeta MateiОценок пока нет

- The Tiger: William BlakeДокумент19 страницThe Tiger: William BlakeMohammad Suleiman AlzeinОценок пока нет

- Liturgical DramaДокумент2 страницыLiturgical DramaSohailRanaОценок пока нет

- Tom Jones 1Документ5 страницTom Jones 1oldschoolarijitОценок пока нет

- An Introduction To A House For MR Biswas PDFДокумент6 страницAn Introduction To A House For MR Biswas PDFSarba WritesОценок пока нет

- Respponse To Walking in MoonlightДокумент1 страницаRespponse To Walking in Moonlightapi-438963588100% (1)

- Structure and Plot of AntigoneДокумент5 страницStructure and Plot of AntigonedlgirОценок пока нет

- Saadat MintoДокумент9 страницSaadat MintoMustafa KhattakОценок пока нет

- Presented To: Dr. Archana Awasthi: A Study of Provincial LifeДокумент7 страницPresented To: Dr. Archana Awasthi: A Study of Provincial LifeJaveria MОценок пока нет

- Because I Could Not Stop Download in PDFДокумент2 страницыBecause I Could Not Stop Download in PDFAbdul WaheedОценок пока нет

- Eunice de SouzaДокумент3 страницыEunice de SouzaManya ShivendraОценок пока нет

- The Romantic Age 1 (Cenci As A Revenge Tragedy)Документ9 страницThe Romantic Age 1 (Cenci As A Revenge Tragedy)ManikandanОценок пока нет

- Shelley's OdeДокумент17 страницShelley's OdedebarunsenОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Samuel RichardsonДокумент22 страницыIntroduction To Samuel RichardsonKavisha AlagiyaОценок пока нет

- Yayati (Girish Karnad) Summary by Dr. Himanshu Kandpal (MP3 160K)Документ4 страницыYayati (Girish Karnad) Summary by Dr. Himanshu Kandpal (MP3 160K)Dhanush NОценок пока нет

- Jane Austen Art of CharacterizationДокумент4 страницыJane Austen Art of CharacterizationSara SyedОценок пока нет

- What Are The im-WPS OfficeДокумент7 страницWhat Are The im-WPS OfficeSher MuhammadОценок пока нет

- Chief Characteristics of Dryden As A CriticДокумент4 страницыChief Characteristics of Dryden As A CriticQamar KhokharОценок пока нет

- Study Guide to The Vicar of Wakefield by Oliver GoldsmithОт EverandStudy Guide to The Vicar of Wakefield by Oliver GoldsmithОценок пока нет

- Ivana Curent LitДокумент6 страницIvana Curent Litellen20Оценок пока нет

- An Essay On Man 432107Документ2 страницыAn Essay On Man 432107ellen20Оценок пока нет

- Elective DP 2Документ8 страницElective DP 2nochefОценок пока нет

- A Midsummer Night2Документ2 страницыA Midsummer Night2ellen20Оценок пока нет

- Summary of Robinson CrusoeДокумент4 страницыSummary of Robinson Crusoeellen20100% (2)

- An Essay On Man 432107Документ2 страницыAn Essay On Man 432107ellen20Оценок пока нет

- A Midsummer NightДокумент2 страницыA Midsummer Nightellen20Оценок пока нет

- Summary of Robinson CrusoeДокумент4 страницыSummary of Robinson Crusoeellen20100% (2)

- An Essay On Man 432107Документ2 страницыAn Essay On Man 432107ellen20Оценок пока нет

- An Essay On Man 432107Документ2 страницыAn Essay On Man 432107ellen20Оценок пока нет

- DPI Vs PPI - What Is The Difference - Photography LifeДокумент90 страницDPI Vs PPI - What Is The Difference - Photography LifePavan KumarОценок пока нет

- Geo TestДокумент2 страницыGeo Testleta jima100% (1)

- In The Beginning: by Thomas WhiteДокумент2 страницыIn The Beginning: by Thomas WhiteYo AsakuraОценок пока нет

- Lamb of GodДокумент2 страницыLamb of GodChristiana KritikosОценок пока нет

- Dzexams 3am Anglais d1 20180 1052824Документ2 страницыDzexams 3am Anglais d1 20180 1052824fatihaОценок пока нет

- SR20DET Engine Swap GuideДокумент10 страницSR20DET Engine Swap GuideJeff KentОценок пока нет

- Chuck Palahniuk: Beyond The Body A Representation of Gender in "Fight Club", "Invisible Monsters" and "Diary" - Kjersti JacbosenДокумент115 страницChuck Palahniuk: Beyond The Body A Representation of Gender in "Fight Club", "Invisible Monsters" and "Diary" - Kjersti JacbosenCamelia PleșaОценок пока нет

- Greek NameДокумент10 страницGreek Namecermjh21Оценок пока нет

- BWSSB 07-03-2018 SorДокумент184 страницыBWSSB 07-03-2018 Sorkathir1965Оценок пока нет

- Lab 1Документ39 страницLab 1Nausheeda Bint ShahulОценок пока нет

- EDCI 517 F17 Reaves SyllabusДокумент9 страницEDCI 517 F17 Reaves Syllabusfostersds1Оценок пока нет

- Ma EnglishДокумент19 страницMa EnglishKAMALSUTHAR6061AОценок пока нет

- Channels ListДокумент2 страницыChannels Listphani raja kumarОценок пока нет

- The Man Who Sold The WorldДокумент9 страницThe Man Who Sold The WorldJoell Rojas MendezОценок пока нет

- Kusile Power Station South Africa: EnterprisesДокумент50 страницKusile Power Station South Africa: EnterprisesDeepak DasОценок пока нет

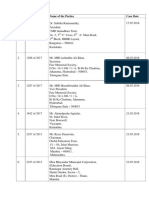

- S.No. Case No. Name of The Parties Case Date: RD TH NDДокумент4 страницыS.No. Case No. Name of The Parties Case Date: RD TH NDAasim Ahmed ShaikhОценок пока нет

- A 0308003Документ196 страницA 0308003Kissy De Las Mercedes Pérez Bustamante0% (3)

- The Art of Black Magic and Witchcraft: AbstractДокумент4 страницыThe Art of Black Magic and Witchcraft: AbstractNyana PrakashОценок пока нет

- 1066-And All That (1930)Документ129 страниц1066-And All That (1930)shauniya83% (12)

- Making Better ChoicesДокумент2 страницыMaking Better Choicesapi-465849518Оценок пока нет

- Curriculum Map ENGLISH 2 Edited PRINTED 1-4Документ11 страницCurriculum Map ENGLISH 2 Edited PRINTED 1-4Jo MeiОценок пока нет

- House On Mango Street PowerpointДокумент3 страницыHouse On Mango Street Powerpointapi-500884712Оценок пока нет

- GP Welcome Tune List 2015Документ2 страницыGP Welcome Tune List 2015AlexОценок пока нет

- Survey To American Literature 1Документ573 страницыSurvey To American Literature 1Mirana Rogić100% (1)

- Gujarati Samaj Guest HousesДокумент3 страницыGujarati Samaj Guest HousesjitmОценок пока нет

- Chapter 4 Fashion CentersДокумент48 страницChapter 4 Fashion CentersJaswant Singh100% (1)

- Ted Harrison Art Work DecДокумент4 страницыTed Harrison Art Work Decapi-384125792Оценок пока нет

- Sequence of Works For Building ConstructionДокумент2 страницыSequence of Works For Building ConstructionBoni Amin76% (34)

- Linking Words of Reason PracticeДокумент2 страницыLinking Words of Reason PracticeMarisa SilvaОценок пока нет

- 66 Fluency Boosting German Phrases PDFДокумент13 страниц66 Fluency Boosting German Phrases PDFAyesha ChaudryОценок пока нет