Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Intimacy in Recovery PDF

Загружено:

sunkissedchiffonИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Intimacy in Recovery PDF

Загружено:

sunkissedchiffonАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Intimacy in Recovery

By Tian Dayton, PhD, TEP When a couple is in recovery from their own or their partners drug abuse or alcoholism they each need stability, support and intimacy more than ever, but they are usually terrified by the thought of it. True intimacy requires that each partner allows him or herself to be vulnerable and dependent, but because their ability to be intimate with one another has been traumatized by addiction, they might both be afraid that allowing themselves to be open and responsive will lead to further violations of faith, hope and trust. Making sense of an addicted relationship The intimate relationships of addicts evolve, over time, to mirror their own inner world. Unmodulated affect, unreliability and an emotional climate that alternates between shutdown and over-reaction characterize both the worlds of the addict and his/her relationships. When the substance is removed, couples are at risk for living out the dysfunctional patterns that became fixed while one or both partners were using. Partners may view each other through distorted lenses, that is, they assess themselves, each other and their relationship using the meaning that represented their best attempt at making sense of an addicted partnership. It is as if an ice storm has frozen dysfunctional relationship dynamics in place and both partners continue to navigate by that map even when the addictive behaviors and substances are removed. They are suited up for the wrong weather trained for a different event. The trauma of addiction Couples who have been traumatized by addiction need to overcome the learned helplessness (van der Kolk, 1996) that was set in motion when they repeatedly felt that they could do nothing to help or change their painful pattern of relating. The emotional intensity that characterized their partnership needs to give way to real, rather than distorted reasoning.

The hyper vigilance (Krystal, 1968), that keeps them so on the alert for problems that they continually create them, needs to be made conscious so that they can relax as a couple. Along with their need to delve into distorted meaning established during addiction is the task of examining the impact that family-of-origin issues had on their propensity to manage emotional and psychological issues with mood-altering substances and behaviors or to choose partners who do so. Traumatic bonds from early painful relationships where there was an imbalance of power and isolation (Allen, 1996) can lead to negative transferences from parents onto partners. Splitting may occur where partners see each other through the magical mind of the child alternating between all good (able to meet and gratify all needs and wishes) and all bad (out to harm, wound and abandon). Negative modeling and mirroring from childhood that may have taught partners to see themselves and/or relationships in a negative light may need to be reexamined. Slowly the couple can restore and rebuild both themselves and their relationship until they develop the strength and resilience necessary to right themselves on their own when they get into distress. Chronic relationship disconnection All relationships, even healthy ones, cycle through periods of connection, disconnection and reconnection. Its the natural ebb and flow of family, friendship or partnership. In healthy partnerships the reconnection is usually a small step up (Baker-Miller, et al., 1997), that is, we learn a little something about getting along from our temporary feeling of disconnection and bring it into the reconnection (ibid.). For those who have experienced addiction and trauma in their intimate relationships, however, the types of disconnections that occur are much more serious. These experiences of disconnection lead people to form relational images of others as people who cannot understand them, cannot feel with them, will leave them in isolation, will not be there for them, will scorn, humiliate or abuse them. Then they develop a variety of responses such as compliance, silence, serving and responding to others needs, not asking anything or outwitting, controlling or triumphing over others (ibid.).

For example, a son of an alcoholic mother may develop a strategy of taking care of her by being a surrogate partner, a good listener or caretaker. Or the wife of an alcoholic husband may develop a pattern of compliance. These types of relationship disconnects create cauldrons of emotional and psychological pain that can and often do lead to addiction or are part of addicted relationships. Self-medicating and addiction Bessell van der Kolk, in his seminal research on trauma, found that one of the pervading symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) both in soldiers and those who have experienced some form of physical, sexual or emotional abuse, neglect or living with addiction, is the desire to self-medicate with drugs or alcohol. Bessell van der Kolk defines trauma as a rupture in relationship bond. People who have been in intimate partnerships with addicts and addicts themselves have experienced these deep fissures and can feel hesitant to form intimate connections, as they fear another relationship rupture. In recovery from addiction when the self-medicator is removed, the emotions and psychological problems that were being quieted by using substances emerge with even greater intensity. Treatment issues and dysfunction in intimacy Meet Jane and Bill. Bill is the second addict in Janes life; her first was her father. She learned her lessons on intimacy from modeling her parents alcoholic dynamic, and her first love her father was a practicing alcoholic. From her mother she learned to deny what was in front of her and over function in order to maintain family order and dignity. When she met Bill, a handsome, charming man addicted to alcohol and cocaine, she felt that she had finally found the man I wanted to marry. Bill, on the other hand, came from a military family. An army brat who moved every two years, he grew up watching his parents manage their ever-present tension and emotional ups and downs with an extended cocktail hour during which they each consumed two or three strong drinks a piece. When he met Jane, he felt that she really understood him. Twelve years

and three kids later, Bills law firm gave him a choice get treatment or leave. Here are some of the issues that were waiting for them when Bill sobered up and they entered couples therapy to try to reconstruct their broken relationship: Intimacy: People who have self-medicated with a substance have been emotionally unavailable for the subtle nuances of intimacy. The modulated give and take, each person retaining and maintaining his or herself while integrating the presence of another, trust levels, comfort with openness, honesty and constant negotiation that are all a part of intimacy have been undermined if not nearly destroyed by the pressure of addiction. The couple for whom addiction has played a central organizing role in their relationship may need to learn to rebuild intimacy from the ground up. In treatment, the self of each partner will need to be reaffirmed. To exist in close partnership, both Bill and Jane will need to improve their relationship with themselves in order to be with each other in healthy ways. Commitment: Broken promises, unreliability and ambivalence about commitment have taken their toll on the relationship. Victims of addiction and trauma have often lost faith in love and in their ability to stay in long-term partnerships. Jane and Bill alternate between fear of abandonment and/or engulfment. They fear that they will have to give up a self to stay in a relationship. They feel that they do not have what it takes to make a relationship work in the real world. Treatment will require that they keep their word and fulfill their commitments in a responsible manner so that integrity and reliability can return to their relationship. Communication: Good communication requires that each partner can tune in on their own inner world, articulate it in an emotionally literate manner and listen to their partner do the same. Partners need to accurately read each others subtle signals. They need to learn to listen to each other without being triggered into attacking, withdrawing or

experiencing explosions and implosions of emotions and psychological intensity that shut down communication. In couples therapy, Bill and Jane will need to retrain one another in skills of good communication. One useful technique is to ask one person to stand behind their partner and double for what they feel is going on inside of them. Bill standing behind Jane articulates what he imagines to be her inner world, thus training the ability to tune in on each other. Then the partner accepts or corrects it. Another technique is to ask partners to reverse roles to physically change places with each other and continue the exchange. This allows each person to experience the role of the other so that empathy and understanding can build (Dayton, 1994). Accepting love and support: Bill, the addict, has learned to turn to a substance for intimacy and comfort rather than his partner, Jane. Jane has been isolated from Bill and learned not to need anything that might lead to further pain or disappointment. Both fear that allowing closeness to feel too good, i.e., to let it in, will only lead to more hurt when it inevitably disappears again as it did during addiction. Either they use in an unconscious attempt to prevent further abandonment or they maintain a cool distance. Unconsciously, they imagine theyre protecting themselves from further pain by staying hyper vigilant while, in truth, theyre keeping out pleasure and love. The truth is that closeness ebbs and flows. But for those who have been deeply wounded that ebb and flow can become hard to tolerate. Hurt couples want to fix it, to not hurt ever again. They will need to learn that its natural to move in and out of intimacy and not to feel their relationships not working if their co-state cycles through connection and disconnection. Boundaries: The addict has forfeited the ability to say no to themselves and/or to modulate their use of a substance. The substance itself has dictated terms of involvement invading both the personal and relationship world with the force of a natural disaster mowing down everything in its path. For Bill and Jane, setting meaningful limits, which are a natural outgrowth of a genuine connection with self and a realistic understanding of the dynamics of the relationship, becomes difficult. Boundaries have been rigid or rubber depending not on a realistic sense of self and relationship, but on surviving dysfunction day to day. In a chaotic partnership where patterns of fusing vs. disconnection and aggression vs. withdrawal are the norm, it is difficult to know where one person leaves off

and the other begins. Boundaries set in this emotional climate tend to be arbitrary and inconstant. The treatment will require a methodical rebuilding of self and relationship. Boundaries will then be about maintaining a sense of self WHILE in deep connection with another and allowing the other person to do the same through attunements, respect and negotiation. Modulating Emotion: Psychological and emotional trauma undermine an addicts and co-addicts ability to modulate emotion. The emotional climate of the relationship becomes characterized by extremes of shutdown and withdrawal alternating with emotional intensity and high affect; hence the black-and-white world of the addict in relationship with self and partner (van der Kolk, 1994). When intense emotional extremes are the rule, Bill and Jane seesaw between conflict and withdrawal, being easily triggered into intense anger and/or emotional and psychological numbness. Trust and Faith: The addict loses trust and faith in self, others and life. The person in an intimate relationship with the addict experiences constant disappointment and disillusionment that undermines trust. They need to be rebuilt along with the self, as the addict reconstructs a selfregulated inner world. People in addicted relationships have often lost faith in their relationships ability to repair and renew itself. Their pain-filled partnership may have invaded many aspects of their life, throwing not only their marriage but other areas of their life out of balance. They lose faith in an orderly, predicable world. In this way, addiction and coaddiction can become a spiritual disease as those involved lose hope of a better life. Having Fun: Spontaneity and relaxation for the addict have been dependent upon a substance-induced state. It is a task to learn how to have fun in recovery. For the co-addict, spontaneity means out-of-control or on the edge of chaos. In the recovering relationship, the addict and coaddict need to consciously learn to engage in activities that bring pleasure. Bill and Jane need to plan fun into their lives in whatever way feels meaningful to them. Dinners, socializing and shared hobbies can all be ways of restoring pleasure and play. Sexuality: Sex while under the influence of a substance is different from

sex while sober. Bill will need to relearn enjoyment and ease with sober sex. Men tend to use sex to connect emotionally while women tend to want an emotional connection in order to become aroused (Gray, 1996). Because she felt emotionally distant from Bill, Jane withdrew sexually. Sex while Bill was high gratified her physically, but felt humiliating. Healing in this area will require patience and practicing new behaviors. Masters & Johnson-type tapes and sex therapy are useful to the recovering couple. Less emphasis on intercourse with more time given to foreplay and afterplay can extend the pleasure of sex and reduce the anxiety around performance. Dates and romance need to be consciously scheduled and enjoyed. According to Stephanie Covington, PhD, of The Institute for Relational Development in La Jolla, California, some of the factors a therapist will need to identify in clients during treatment are: * The capacity to have observer ego and self-regulation * Family-of-origin patterns * Communication * The individuals defensive structure * Each persons ability to seek self needs from others

Intrapsychic and lived reality of wish Covington finds that effective treatment often involves encouraging one or both partners to maintain their own beliefs, even if they seem antithetical to effective sexual and marital functioning. The emergence of a greater solid self in at least one partner often has a catalytic impact on the development of both individuals and enhances intimacy and sexual

intensity. An assessment instrument for couples Following is a self-assessment tool for couples. It is designed to help each partner reflect on psychodynamic issues related to living with trauma and addiction that may be affecting their relationship. It can be used in therapy as a springboard for exploration and as a tool to help bring relevant issues into focus. It can be filled in as homework or in the presence of a therapist. For more in-depth information on this subject refer to Trauma and Addiction: Ending the Cycle of Pain Through Emotional Literacy and Heartwounds: The Impact of Unresolved Trauma and Grief on Relationships both by this writer and published by Health Communications, Inc. Conclusion Over the course of treatment, couples will need to learn to self-soothe without the use of chemicals or acting out behaviors. Learning to observe or witness their own internal process will eventually allow them to talk out rather than act out emotions and to tune in on their internal worlds in a non-reactive manner. Dysfunctional defensive structures that impair intimacy will slowly be dismantled while more functional behaviors replace them. The couple can explore what needs can be met by their partner, which needs they will need to go outside the partnership to meet and which are fantasies that have more to do with a wish for the perfect parent than a reasonable expectation of a partner. For the couple who can plow through this complicated terrain, intimacy can feel like a stolen treasure that they will guard with their lives. They can develop the vision, as C. S. Lewis said, that it takes two to see one and use their relationship for self-actualization.

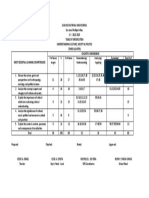

-----------------------------------------------------------------------Answer the following questions by placing a check "a" in the appropriate box.

Self Assessment Tool for Couples

To what extent do you: Very Little Somewhat Quite a Bit Very Much

1. Avoid intimate relationships because you unconsciously fear another interruption of the affiliative bond? 2. Recreate relationship dynamics that mirror your worst nightmare? 3. Project unhealed pain and anger from earlier relationships onto your current intimate relationship? 4. Become enmeshed or fused in intimate relationships in an unconscious attempt to protect against abandonment? 5. Distance your partner when you enter an interdependent relationship? 6. Respond to situations that trigger you by shutting down or with an intensity of emotions appropriate to earlier relationships or traumatic times in your relationship? 7. See your partner as alternately all good or all bad? 8. Misread signals from your partner? 9. Overreact to signals that threaten to stimulate old pain? 10. Lose the ability to let go and be playful in intimate relationships? 11. Lose the ability to trust and have faith in intimate relationships? 12. Fear being smothered or engulfed by your relationshhips? 13. Lose your ability to accept support? 14. Get easily triggered into anger, tears or withdrawal? 15. Have trouble keeping your commitments in relationships? 16. Have a hard time saying what you really mean or feel? 17. Have trouble listening or staying present during emotionally charged conversations without withdrawing or becoming overly aggressive? 18. Have a hard time figuring out where you leave off and your partner begins? 19. Have trouble setting and maintaining your own boundaries and/or respecting those of your partner? 20. Manifest relationship problems in the area of sexuality? 21. Feel helpless to affect or create change in your relationship?

22. Feel numb, shutdown or emotionally constricted in your relationship? 23. Become hyper vigilant in your relationship constantly scanning for problems? Tian Dayton, PhD, TEP, is director of Program Development and Staff Training for the Family and Couples Programs, Caron Foundation, Wernersville, Pennsylvania, New York City. She holds a doctorate in clinical psychology, a Master's in educational psychology and is a fellow and certified trainer of the American Society for Psychodrama, Sociometry and Group Psychotherapy. She is the author of many books, including "Drama Games", "The Drama Within", "Affirmations for Parents", "Forgiving and Moving On" and "Trauma and Addiction."

Вам также может понравиться

- The Shame Experiences of The Analysts-R Stein PDFДокумент8 страницThe Shame Experiences of The Analysts-R Stein PDFsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Iapt, Ph9, EtcДокумент1 страницаAssessment, Iapt, Ph9, EtcsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- BeGudd - Issue Nr. 6 2020Документ80 страницBeGudd - Issue Nr. 6 2020sunkissedchiffon38% (53)

- B08LT728MSДокумент501 страницаB08LT728MSSandy FireОценок пока нет

- Hip Pain Assessment Form: Date Name Points I - Pain or DiscomfortДокумент2 страницыHip Pain Assessment Form: Date Name Points I - Pain or DiscomfortsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Images TreatmentДокумент4 страницыAssessment, Images TreatmentsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Knee LequesneДокумент2 страницыAssessment, Knee LequesnesunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- HDS Manual PDFДокумент73 страницыHDS Manual PDFsunkissedchiffon100% (1)

- Assessment, Life HighlightsДокумент1 страницаAssessment, Life HighlightssunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Track Changes in Feelings During Imagery RescriptingДокумент2 страницыTrack Changes in Feelings During Imagery RescriptingsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Interpersonal Iip-48, TДокумент3 страницыAssessment, Interpersonal Iip-48, TsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Hip & Knee ScoreДокумент1 страницаAssessment, Hip & Knee ScoresunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Intrusive Memories - 0Документ2 страницыAssessment, Intrusive Memories - 0sunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Images WeekДокумент2 страницыAssessment, Images WeeksunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Images DetailsДокумент3 страницыAssessment, Images DetailssunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Images BackgroundДокумент4 страницыAssessment, Images BackgroundsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Experiencing Scale - 1Документ2 страницыAssessment, Experiencing Scale - 1sunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Ibs Severity, TДокумент3 страницыAssessment, Ibs Severity, TsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Espie Overall ProgressДокумент1 страницаAssessment, Espie Overall ProgresssunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Expectancy & CredibilityДокумент2 страницыAssessment, Expectancy & CredibilitysunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Fatigue SeverityДокумент1 страницаAssessment, Fatigue SeveritysunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Fatigue TirednessДокумент2 страницыAssessment, Fatigue TirednesssunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Experiencing Scale - 1Документ2 страницыAssessment, Experiencing Scale - 1sunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Espie Diary FormДокумент2 страницыAssessment, Espie Diary FormsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Erectile Dysfunction ScaleДокумент1 страницаAssessment, Erectile Dysfunction ScalesunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Erectile Dysfunction ScoringДокумент1 страницаAssessment, Erectile Dysfunction ScoringsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Dyadic Adjustment ScoringДокумент1 страницаAssessment, Dyadic Adjustment ScoringsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Diener SwlsДокумент1 страницаAssessment, Diener SwlssunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Disability, 0-8 Five Areas, ScoringДокумент1 страницаAssessment, Disability, 0-8 Five Areas, ScoringsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Assessment, Diener Swls BackgroundДокумент3 страницыAssessment, Diener Swls BackgroundsunkissedchiffonОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- TDCCBCSArabic Syllabus 2017Документ24 страницыTDCCBCSArabic Syllabus 2017Januhu ZakaryОценок пока нет

- What Is A Minimum Viable AI ProductДокумент10 страницWhat Is A Minimum Viable AI Productgradman2Оценок пока нет

- Reyes BRJ 2004Документ22 страницыReyes BRJ 2004Sharan RajОценок пока нет

- PedagogiesДокумент45 страницPedagogiesVictoria Beltran SubaranОценок пока нет

- Laws of Body Language Answer KeyДокумент4 страницыLaws of Body Language Answer KeySvrbishaОценок пока нет

- Inset EVALuationДокумент1 страницаInset EVALuationGinangОценок пока нет

- Tos - Ucsp 3rd QRTRДокумент1 страницаTos - Ucsp 3rd QRTRJessie IsraelОценок пока нет

- Visual Weight Cheat Sheet NewДокумент1 страницаVisual Weight Cheat Sheet NewRicardo W. BrandОценок пока нет

- Notes 8 SubmodalitiesДокумент17 страницNotes 8 Submodalitiesигнат дълбоковОценок пока нет

- Lesson Plan SkippingДокумент6 страницLesson Plan Skippingapi-400754898Оценок пока нет

- Orgs Open Systems PDFДокумент3 страницыOrgs Open Systems PDFYàshí ZaОценок пока нет

- Entrepreneurial IntentionДокумент24 страницыEntrepreneurial IntentionGhulam Sarwar SoomroОценок пока нет

- Science of Psychology An Appreciative View 4th Edition King Test Bank 1Документ45 страницScience of Psychology An Appreciative View 4th Edition King Test Bank 1derek100% (42)

- Spiral CurriculumДокумент17 страницSpiral Curriculumharlyn21Оценок пока нет

- My PaperДокумент5 страницMy PaperAbraham Sunday UnubiОценок пока нет

- Module 1Документ5 страницModule 1Janelle MixonОценок пока нет

- "Improving Reading Comprehension Skills Through The Implementation of "Recap" For Grade 2 Wisdom Learners"Документ5 страниц"Improving Reading Comprehension Skills Through The Implementation of "Recap" For Grade 2 Wisdom Learners"Erich Benedict ClerigoОценок пока нет

- Business Seminar Notes-2021-1Документ41 страницаBusiness Seminar Notes-2021-1Meshack MateОценок пока нет

- Relaxed Pronunciation ReferenceДокумент8 страницRelaxed Pronunciation Referencevimal276Оценок пока нет

- Definition of M-WPS OfficeДокумент2 страницыDefinition of M-WPS Officekeisha babyОценок пока нет

- Explainable Sentiment Analysis For Product Reviews Using Causal Graph EmbeddingsДокумент22 страницыExplainable Sentiment Analysis For Product Reviews Using Causal Graph Embeddingssindhukorrapati.sclrОценок пока нет

- Plan of Study Worksheet 1Документ9 страницPlan of Study Worksheet 1api-405306437Оценок пока нет

- Queen Mary College, Lahore: Submitted To: Miss Shazia Submitted By: Saba Farooq Rimsha KhalidДокумент5 страницQueen Mary College, Lahore: Submitted To: Miss Shazia Submitted By: Saba Farooq Rimsha KhalidMomna AliОценок пока нет

- What Is Instructional Design?Документ33 страницыWhat Is Instructional Design?ronentechОценок пока нет

- Lecture 6. SelfДокумент11 страницLecture 6. SelfAkbibi YazgeldiyevaОценок пока нет

- This Content Downloaded From 107.214.255.53 On Sat, 26 Feb 2022 22:32:57 UTCДокумент20 страницThis Content Downloaded From 107.214.255.53 On Sat, 26 Feb 2022 22:32:57 UTCRicardo SchellerОценок пока нет

- Concepcion Integrated School MAPEH Lesson LogДокумент3 страницыConcepcion Integrated School MAPEH Lesson Logdaniel AguilarОценок пока нет

- PLANNING LANGUAGE LESSONSДокумент6 страницPLANNING LANGUAGE LESSONSGii GamarraОценок пока нет

- Student Copy of COM105 SyllabusДокумент25 страницStudent Copy of COM105 SyllabusTSERING LAMAОценок пока нет

- A Review of Object Detection TechniquesДокумент6 страницA Review of Object Detection TechniquesrmolibaОценок пока нет