Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

03 - Identifying Customer Needs

Загружено:

Jeffrey Jair Murillo MendozaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

03 - Identifying Customer Needs

Загружено:

Jeffrey Jair Murillo MendozaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CHAPTER 3

IDENTIFVING CUSTOMER

NEEDS

Developed in coll aboration with Jonathan Sterrett.

EXHIBIT 1 Exisl ing producls used lo drive screws : manual screwdrivers. cordless screw-

driver, screw gun, cordless drill with driver bit. (Stuart Cohen)

Asu ccessful hand tool manufacturer was explo ri ng the growing market for

hand-held power tools. Ate r performing initial res earch, the firm decided lO

enter th e market with a cordless screwdriver, Exhibit 1 shows several existing

produces uscd to drive screws. Arrer sorne initial concept work, the manufactur-

e r 's d evclopment team rabi icated and field-r estcd severa] prOlotypes. The results

were d iscoui aging. Although so rne of th e products were liked bettcr than others,

each o ne had SO IlH' Icature i hat cus romers object ed to in u ne way o r another,

The rc sults were quite m)"stil )'ing slice th e company li ad been su cc essful in relat-

ed consumer products 1'01' years. Aft er much discussion, the team decided that

it s process for id entifying custorner nceds was inadequate.

This chapte r presents a methodol ogy for comprehensively id entifying a set 01'

cus to rner needs. The goal s 01' th e methodology are lo:

Ensure that the product is focused on cus tomer needs

Id entify latent o r hidden necds as well as explicit needs

Provide a fact base rol' justifying th e product specificatio ns

Cr ea re a n archival r ecord of th e needs activi ty o f the development proces s

Ensure that no critical customer need is missed or forgotten

Develop a common understanding 01' cus to mer needs a mong the develop-

ment team members

The philosophy behind the methodology is 10 create a hi gh-quality informa-

tion channel that runs di r ectly between customers in the target market and the

d evelopers of the product. This philosophy is built on the premise that those

who directly control the details 01' the product, including the engineers and

industrial d esigners, must interact with cus tomers and experience the use envi-

ronment 01' the product. Without this emphasi s on direct experience, technical

trade-offs are not likely to be made corr ectly, innovati ve solutions 10 cus torner

needs may never be discovcred, and the development team may never develop a

deep co mmitme n t to meeting customer needs.

The process of identifying customer needs is an integral part of the larger

product development process and is most dosely rclated to concept generation,

concept sel ectio n, co mpe ti tive benchmarking, and the establishment of product

specifications. The cus to mer-needs activity is shown in Exhibit 2 in relation to

th es e other early product d evelopment activities, whi ch collec tively ca n be

thought 01'as th e ronrei)! druelopment phase .

The coucept developrucm phase illusuated in Ex h ibit 2 implies a di stinction

between customer needs and product speci fications. This distinction is subtle

but important. Needs are largely independent of any particular product we might

develop; they are not specific to the conce pt we eventually choose to pursue. A

team sh ould be able to identify custorner n eeds without knowing if 01' how it will

eventually address those needs. On the other hand, specifi cations do depend on

the concep t we sel ect. The specifica tio ns for the product we finall y choose to

d evelop will depend on what is technically and economically feasible and on

34

e H APTER 3 : I DE NT I FYI NG e U3 TOMER NE o s 35

.1

Plan

Remaining

Devel opment

Projeet

r:; I

Specifications !

I

r

Seiact a

Produ et

Concep

r--

r . Perform

Econornic

Analysis

Esl abhsh H

'

Generare

Targe! Prcduet

Spscifi cat icns I Concepts

L--_--.J

1

_ _ __L

Ail a,yz;l

Cornpeti tive

Produets

Idenlify

Custo rner

Needs

- - - - - - - - - - - - CONCEPT DEVELOPMENT --- - --- - --- -

I

I

l.

Mission

statomcnt

EXHI BIT 2 The custorner-needs activity in relation to other concepl development activities.

what uur competitors o fc r in th e marketplace, as well as un custorn er needs.

(See the chapter "Establishing Pr oduct Specifi cations" for a more detailed dis-

cussion of thi s di stinction.) Also note th at we choose to use th e word need to label

any attr ibute of a potential product th at is desired by the cus to mer ; we do not

di stingui sh he rc betwecn a want ancl a neecl . Other terms uscd in industrial prac-

tice to refer l o customer ne cds include customer auributes and customer require-

ment s.

Identi fyin g custo rner needs is itself a process, for whi ch we pres ent a six-stc p

methocl ology. We believe th. u a little str uct urc goes a long \Vay in fac ilita ti ng

effective product development practi ces, and we hope and expect that thi s

rnethodology will not be viewe d as a ri gid process by th ose wh o ern ploy it but

rather as a stan ing poin t for co utinuous improvement and refinement. The six

ste ps are :

1 Define th e scope of the e ffor t.

2 Gather raw data frorn cus to rners.

3 Interpret th e raw data in terms of cus to rner needs.

4 Organize i he necds into a hi erarchy of primal) ', seco ndary, and (if neces-

sa ry) terti .uv n ce rls.

5 Est ahli sh lile re la rivc- illlporl;lllc e of rhc- I ]( '( ds.

ti Refl cct on 1he results and th e process.

We treat each of th e six steps in turn and illustrat e the key points with th e

cordles s screwdriver exa mple . \Ve chose the scr ewd river because it is simple

enough that the methoclology is not hidden by the co mplexity of the example.

However, note th at th e same methodology, with minor adap tation , has been suc-

cessfull y a pplied to hundreds of products ranging fr orn kitcheri utensils cos ting

less than $10 to machin e tool s costi ng hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The cordless screwclriver caregory of product s is alr eady reJativel y well devel-

36 PAODUCT DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

o ~ e d . Su ch products are parti cularl y well sui ted to a structured process for gath

en ng custorner needs, One could re asonably ask whether a structured method-

ology is effectivc for cornple tely new categories of products with which customers

have no experience , Satisfyirig necds is just as important in revolutionary prod-

\ICL'\ as in inciemental products. A nccessary condition for product success is that

a product offer perceived benefits to the custorner. Products offer benefits when

th ey satisfy needs. This is true whether the product is an incremental variation

on an cx isti ng product 0 1' whether it is a completel y new product based on a rev-

olu tio nary invcntion. Developing an en tirely new category of product is a risky

undertaking, and to sorne extent the only real indication of whether customer

needs have been identified correctly is whether customers like the tearn's first

prototypes. Nevertheless, in our opinion, a str uctured methodology for gather-

ing dat a from customers remains useful and can lower the inherent risk in

devel oping a radicalIy new product. Whether or not customers are able to fuIly

art iculate th eir latent needs, inte raction with customers in the target market will

help th e deveIopment tearn develop a personal understanding of the us er's envio

ronment and point of view. This information is always useful, even if it does not

re sult in the identification of every need the new product wiII address.

STEP 1: DEFINE THE SCOPE OF THE EFFORT

For completeness we inelude defining the scope of th e product development

effort as pan of the customer needs phase of development, although this step is

usualIy performed as part of a product planning activity preceding formal prod-

uct development. In defining the scope of the development effort the firm spec-

ifies a particular mark et opportunity and lays out the broad constraints and

objectives for the project. This information is frequently formalized as a mission

statement (also sorne times called a charter or a design lniej) . The mission statement

specifies which direction to go in but generally does not specify a precise desti-

nation or a particular way to proceed. The mission statement for the cordless

screwdriver is shown in Exhibit 3. The mission statement may in elude sorne or

all of the following information:

Brief (one-sentence) description 01 the product: This description typically

ineludes the key customer benefit of the product but avoids implying a spe-

cifi c product concept.

Key business goals: Often these goals in elude th e timing of th e new product

in tro duction, market sh are targets, and desired financial performance.

Target market(s) larthe product: There may be several target markets for the

product. This part ofthc mission statement identifies the primary market as

well as any secondary markets that should be considered in the deveIop-

ment effort.

Assumptions that constrain the deuelopment effort: Assumptions must be made

CHAPTER 3 : IDENTI FYING CUSTOM ER NE EDS 37

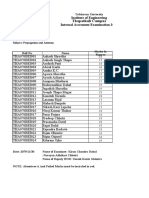

Miss ion S!atement : Screwdriver Project

Product

Description

Ksy Business

Goals

Primary Market

Secondary Markets

Assumptions

Stakeholders

A hand-held. power-assisted de,..ice ' ~ i:l stall ing threadeci

Iasteners

Product introducsd in tourth quarter of 1997

50% gross margin

10% share ot cordless screwdriver market by 1999

Do-it-yourself consumer

Casual consumer

Liqht-duty professiona l

Hand-held

Power-assi sted

Nickel-metal-hydride rechargeable battery technology

User

Retailer

Sales torce

Service center

Production

Legal department

EXHIBIT 3 Mission statement tor the cordless screwdriver.

ca re fu lly; alt ho ugh th ey restri ct the range of possibl e product concep ts,

they help to maintain a manageabl e project scope. We have already implie d

o ne assumption in our example by cal!ing the product a cordless screwd riv-

el'. The implication is that th e screwdriver will be powered but wil! not use

a corded power supply.

Stakeholders: One way to ens urc that many of the subtic development issues

are add ressed is to explicitly list al! of th e product' s stakeholders, th at is, al!

01' the gro llps 01' peoplc wh o are affect cd by th e product's a u rib u tcs, Thc

stakeholder list begins " 'Ih 1111" end u se- r (the ulr ima tr-. c xtcrn al (' 11"" '1 11<' 1 '

.uu t lil e ex te rna! cus to me r wh o makes th e buying deci sion about th e prod-

uct. St akeholders also include the customers of the product wh o reside

within th e firm, such as the sales force, the service organization, and th e

production departments. Although this chapter is primarily about identify-

ing the needs of external chst omers, the list of st akcholders serves as a

rerninder to consid er th e needs of eve ryone who will be influenced by th e

product.

38 PRODUCT DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

STEP 2: GATHER RAW DATA FROM CUSTOMERS

Consistent with our basic philosophy of creating a high-qual ty information

channel directly frorn the customer, gathering data involves contact with cus-

tomers and experience with the use environrnent of the product. Three meth-

ods are commonly used:

1 Interviews: One or more dcvelopment tearn mernbers discuss needs with a

single customer. Interviews are usually conducted in th e customer's envi-

ronment and typi cally last one to two hours.

2 Focus groups: A moderator facilitares a two-hour discussion with a group of

8 to 12 customers. Focus groups are typically conducted in a special room

equipped with a two-way mrror allowing several members of the develop-

ment team to observe the group. The proceedings are usually videotaped.

Parti cipants are usually paid a modest fee ($50 to $100 each) for their atten-

dance. The total cost of a focus group, including rental of the room, par-

ticipant fees, videotaping, and refreshments is about $2,000. In most U.S.

cities, firms that rent focus group facilities are listed in the telephone book

under "Market Research."

3 Obseroing the product in use: Watching customers use an existing product or

perform a task for which a new product is intended can reveal important

details about customer needs. For example, a customer painting a house

may use a screwdriver to open paint cans in addition to driving screws.

Observation may be completely passive, without any direct interaction with

the customer, or may involve working side by side with a customer, allowing

members of the development team to develop firsthand experience using

the product. For sorne products, such as do-it-yourself tools, actually using

the products is simple and natural; for others, such as surgical instruments,

the team may have to use the products on surrogate tasks (e .g., cutting fruit

instead of human tissue when developing a new scalpel) .

Sorne practitioners also rely on written surveys for gathering raw data. While

a mail survey is quite useful later in the process, we cannot recommend this

approach for initial efforts to identify customer needs; written surveys simply do

not provide enough information about the use environment ofthe product, and

they are ineffective in revealing unanticipated needs.

Research by Griffin and Hauser shows that one 2-hour focus group reveals

about the same number of needs as two l-hour interviews (Griffin and Hauser,

1993) . (See Exhibit 4.) Because interviews are usually less costly (per hour) than

focus groups and because an interview often allows the product development

team to experience the use environment of the product, we recommend that

interviews be the primary data collection method. Interviews may be supple-

mented with one or two focus groups as a way to allow top management to

observe a group of customers or as a mechanism for sharing a comrnon customer

experience (via videotape) among the members of a larger team. Sorne practi-

tioners believe that for certain products and custorner groups, the interactions

among the participants of focus groups can elicit more varied needs than are

,

U

Q)

Q)

z 40

e

Q)

o

Q;

Q.

20

CHAPTER 3. iDENTIFYING CUST:JMER NEEDS 39

o One-on-One Interview (1 hour)

o Fccus Group (2 hour)

o 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Number of Interviews or Groups

EXHIBIT 4 Comparison 01 the percentages 01customer needs that are revealed ter locus groups and inter-

views as a lunction 01 the number of sessions. Note that a locus group lasts two hours, while an

interview lasts one hour. (Abbie Griffin and John R. Hauser, "The Voice 01 the Customer,"

Marketing Science, Vol. 12, No. 1, Winter 1993.)

revealed through interviews, although this belief is not strongly supported by

research findings.

Choosing Customers

Griffin and Hauser have al so addressed the question of how many custorners

should be interviewed in order to reveal most of the custorner needs. In one

study, they estimated that 90 percent of the custorner needs for picnic coolers

were revealed after 30 interviews. In another study, they estimated that 98 per-

cent of the custorner needs for a piece of office equipment were revealed after

25 hours of data collection in both focus groups and interviews, As a practical

guideline for most products, conducting fewer than 10 interviews is probably

inadequate and 50 interviews are probably too many. However, interviews can be

conducted sequentially and the process can be terminated when no nc-w needs

are revealed by additional interviews, Teams containing more than 1() pcoplc

usuallv collect data frorn plcnty of customers simplv by involving ever;( .ue in the

1,j(Jl('" FuI' ,,,-,lI"Jk, .. t i n u.uu is di\lllcd I,u tin J<tirs ,tjHi Clcl . ',lir JI1-

ducts {) interviews, the team will conduct 30 interviews in total.

Needs can be identified more efficientiy by interviewing a class of customers

called lead users. According to von Hippel, lead users are custorners who experi-

ence needs months or years ahead of the majority of the marketplace and stand

to benefit substantially from product innovations (von Hippel, 1988). These cus-

tomers are particularly useful sources of data for two reasons: (1) thev are often

able to articulare their emerging needs, because they have had to struggle with

the inadequacies of existing products, and (2) they may have airead" invented

40 PRODUCT DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

I

I

!

I

Retaller or

5e;vlce I

Lead users Users S a l ~ ; ; Outiet

i

Centers

r--

!

I

I Homeowner

D 5

(occaslonal use) I

- -

2

I

Handy person

3 10 3

(frequent use)

Professional

3 2 2

(heavv-dutv use)

EXHIBIT 5 Customer selection matrix lar the cordless screwdriver project.

solutions to meet their needs. By focusing a portion of the data collection efforts

on lead users, th e team may be abl e to identify needs which, although explicit

for lead users, are still latent for th e majority of the marketplace. Developing

products to meet these latent needs allows a firm to anticpate trends and to

leapfrog competitive products.

The choice of which customers to interview is complicated when several dif-

ferent groups of people can be considered "the customer." For many products,

one person (the buyer) makes the buying deci sion and another person (the

user) actually uses the product. A good approach is to gather data from the end

user of the product in all situations, and in cases wherc other types of customers

and stakeholders are clearly important, to gather data from these as well.

Furthermore, ifthere are multiple market segments to be addressed by th e prod-

uct, it is important to gathcr data from each segment in order to understand the

differences in th eir re spective needs.

A cus tomer sel ection matrix is use ful for planning exploration of both market

and customer vari ety. Burchill suggests that market segments be listed on the left

side of th e matrix while the different types of customers are listed across the top

(Burchill et al. , 1992) , as shown in Exhibit 5. The number of intended customer

contacts is entered in each cell to indicate the depth of coverage.

ActualIy locating customers is usualIy a matter of making telephone calIs . In

developing industrial products within an existing manufacturing firm, a field

sales force can often provide names of cu stomers, although the team must be

careful about biasing the sclection of customcrs toward those with alIegiances to

a particul ar manufacturer. The tel ephone book can be used to identify names of

sorne types of customers for sorne classes of products (e.g., building contractors

or insurance agents) . For industrial products that are integral to a customer's

job, getting someone to agree to an interview is usualIy simple; these customers

are anxious to discuss their needs. Also, most consumers are frustrated quite reg-

ularly by products that do not fulfilI their needs-much more often than they are

bothered by surveys and interview requests.

C HAPT ER 3 : I D ENTI F YI NG CUST Oiv1 ER NEE DS 41

The Art of Eliciting Customer Needs Data

Thc tcc.hniqucs wc p resenl hcre a re aimcd primaril v .u intclv iewini-\" e nd U,'itTS,

h ut t hcse metho cls d o a p p '" l O ,d I 0 1' the th rec d a ta -!-',a he - in i-\" l1I o d es a nd 1<: ,tl!

IYH'S 01' sta keho ld crs. The b.i- ic app ro.rch is to he recc pti \'c lo in o rmauo n pro-

\'ided by c u sto me rs .ui d I () avoi d co n rroll ta l io n s 0 1' dcfensi ve p ostu r ing

( ;a lh (Tin i-\" necds d .u a is ,,'el\ d ift e rell t Irom a s a k ~ . ca ll: t h goal is lo rlici t ; lI l

hom-st c xp rr-ssio n u f nf,'l' d s, no t lO cu n\'IlCe a t'US{OIl1l:' r o wh: he o r slu : n ('<' d s,

In most cases CUSlo nHT in u-r. ut io ns will he ve r bal; in ter vi ewers as k q uestions .u irl

the custorne r res po nd s. A prc pa rcd in tcrview g ll iele is va lua ble 1' 0 1' suuctu ring

i h is d ial o gue , Sorne h elplul q uesti ons and pro mpts rol' use a ter th int e rvi c wc-rs

introduce t he msc lves a ud c xpla in i he p u r pose 0 1' i h in tc rvi ew are :

Walk LI S throllgh a typica l sessi o n llsing rhe procluct .

\ Vhat elo vou like abou r t he cxisting p ro duct x?

\Vhat do vo u d isl ikc a bo u : t h t: exisl ing p rocluc tx-

What issucs do yo u consider whe n p u rc hasing the p ro duct -

\Vhat improvern e uts would yo u rnake to the product?

Here are so rn e ge neral hin ts [01' cffective inte racti on with c usto rn c rs:

Co with the flow. Ir the cus to mer is provi ding in te resting in forrna ti o n , d o not

WOIT Y a bou t confo rrning lo th e in terv iew g uide . T h e goal is to gather in te r-

esting a nel important elata on c ustome r n eeds, not lo com p le te the in te r-

view guide in thc allotted time ,

Use visual stimuli aud props. Br in g a collection 01' e xi sli ng an d co m pc tiio rs '

pr oducts, 0 1' even prod uc ts t hat a re tangcn tia lly rcla ted to the product

lindel' deve lo pmcnt. AL the e nd of a sessio n, t h e interviewc rs rn ight evc n

show so mc prelirnin ary product co ncep ts 10 ge t cus to rners' ca rl y reac t ions

to var io us a p p roaches.

Suppress preconceived hypotheses about the product techllOlogy. Frequently ClI S-

torn ers will ma ke as su mptio ns a boli t the p roduc t eo ncep t th ey expe ct would

meet thei r need s. In these si tuati o ns, the in tervi ewe r s sh ould avo id bi asin g

the eliscussion with assu m p tio ns abou t how th e produc t will e ve n tually be

elesigned 01' produce el. When cus torners menr io u specific le chnol ogi cs 01'

prorl uct fc a tur c-s. i h inu-rvi cwr-r shou ld pro be t.... r t li e- 1IlHlerl yin g ne-ed t l n:

cust o rn r-r beli c\'('s t1 1(' k ; , 11IH' \" l) l il rl s:l i -;f\ ' ,

Have the eustomer demonstrate the product and/or typical tasks related to the

producto If the inte rvi e w is co nelucte el in the use e n viron ment , a d emonstra-

ti on is usually co n venie n t an d invariab ly reveaIs new information.

Be alert [or surprises and the expression of latent needs. 11' a custorne r men ti o n s

something su r p r ising, pu rsue the leael wi th fo llow-u p questio n s. Fre qll e nll y,

an unexpeeted line oI' q uestion ing wi ll reveal latcnt ncc ds- im portan t

42 PROOUCT DESIGN ANO OEVELOPMENT

dimensions of the custorners' needs which are neither fulfilled nor corn-

monly articulated and understood.

Watch [or nonuerbal irformation. The described in the chapter is

aimed at developing bettei physieal producrs. Unfortunately, words are not

always th e best \Vay to communicate needs related to the physical world.

This is particularly true 01' needs involving the human dirnensions of the

product, such as cornfort, irnage, 01' style . The developrnent tearn must be

constantly aware of the nonverbal messages provided by customers. What

are their facial expressions? How do they hold competitors' produets?

Note that many of our snggested questions and guidelines assume that the

customer has sorne farniliarity with products similar to the new product under

developrnent. This is alrnost always true. For example, even before the first cord-

less screwdriver was developed, people installed fasteners. Developing an under-

standing of custorner needs as they relate to the general fastening task would still

have been beneficial in developing the first cordless tool. Similarly, understand-

ing the needs of customers using other types of cordless appliances, such as elee-

trie razors, would also have been useful. We can think of no product so revolu-

tionary that there would be no analogous produets 01' tasks from which the

development team could learn. However, in gathering needs relating to truly

revolutionary products with which customers have no experience, the interview

questions should be focused on the task 01' situation in which the new product

will be applied, rather than on the product itself.

Documenting Interactions with Customers

Four methods are commonly used for documenting interactions with customers:

1 Audiotape recording: Making an audiotape reeording of the interview is very

easy. Unfortunately, transcribing the tape into text is very time-eonsuming,

and it can be expensive to hire sorneonc to do it. Also, tape recording has

the disadvantage of being intimidating to sorne customers.

2 Notes: Handwritten notes are the rnost eomrnon method of doeumcnting an

interview. Designating one pcrson as the primary notetaker allows the other

person to concentrate on effeetive questioning. The notetaker should strive

to capture sorne of th e wording of ever)' eustomer staternent verbatim.

These notes, if transcriben imrnediatelv aft er the interview, can be used to

creare a description of the interview that is very close to an actual transeript.

This debriefing immediateIy after the interview also facilitates sharing of

insights between the interviewers.

3 Videotape recording: Videotape is almost always used to doeument a foeus

group session. It is al so very useful for doeumenting observations ofthe cus-

tomer in the use environment and/or using existing produets. tape is

usefui for bringing new tearn rnembers "up to speed" and is also useful as

raw material for presentations to upper managcment. Multiple viewings of

CI-IAPTER 3 ' I DE NTI FY I NG CU8TOM E R N E El' S 43

a vid eo tape of r ustome rs in acti on une n Iar ilita te rh e id eruifi cation of

Iaic nt cllslo me r ne, 'd s, \'ideolaping is !Iso lI SC[uI for t:aptlll many

aspe cts of th e crid uscr's c nvi r on mcn t,

4 Still pllOtog1"!lply: T;lking slides 0 1' photograph-, providcs o " t hc benc-

fil S0 1\ it!CUI"pc ITco "(ling, Thc pri mary ,\Ch'Ullages (,1' still p!1otugraphy are

case o f di spl av o f t hc: photos, excellern image q uality, a nd r ead ily avai lab le-

cqlliplncnl. The priuuuv disacl\'al1ta ge is he rclati v iuability to record

dvnamic informat iou .

T he fin al result 0 1' rh c daia-gathcring phase of th e proce ss is a se t of raw d ata,

usu all y in thc form uf custo rn c r suucments hut fr equen tly supplemented by

video ta pe 01' phol ographs, A data templare implcmeuted with a sp r eadshee t

software package is useful 1'01' o rga n izi ng th cse raw data. Exhibir 6 shows an

example of a portion 01' such a templare. v\'e rcconnuend that th e template be

fill ed in as soon as possibl aft e r the int eract ion wit h the cusiorn cr an d c di ted by

th e ot her d evelopmen t tc.uu members present during th c interaction. The first

column in th e main body 01'the templare indicates the question or prompt that

eli cited th e cus to mer data. The se co n d colu mn is a list o f ve r ba t im st a ternents

the custorner made 01' a n observation of a custorncr action (frorn a videotape or

from direct observation) . The third colu mn co n ta ins the custo rner need implied

by the raw data. Some e m phas is should be pl aced o n in vestigating clues whi ch

may identify potential late nt n ecds, Such clues may be in th e forrn of humorous

remarks, less serious su ggestions, nonverbal inforrnation, 01' o bse rva tio ns and

d es criptions of th e use e nviron mc n t. Techniques or interpreting the raw data

in terms of custo mer n e ecls are gi\' e n in the next se ctiou.

The fin al task in step 2 is ro write t ha nk-you not es to th e customers involved

in th e process . Invariablv, th e tc am will ne ed to so licit further cus to rner infor-

mation, so devel oping a nd maintaining a good rapport with a set of users is

important.

STEP 3: INTERPRET RAW DATA IN TERMS OF CUSTOMER NEEDS

Customer needs a re expressed as written st aternents an d are the result of inter-

preting th e need underlying the raw data gat he red frorn the custorners. Each

starement 01' observati ou (as list ed in tlre- second colu rn n of the d ata template )

may be translated into Iro rn zero 10 seve ra l cus to mer needs. Griflin and Hauser

f " I I I HI tlL 11 mult i pl. : ; \l ; I! : ' h 11'; llhbl l' 111<.' <.uu: i l li l '!'\i( ' \ \ ' 11o l ( ' s into d ill c l l' n l

needs, so it is useful to have more than one team member co n d ucti ng th e trans-

lation process. Below we provide five guidelines for writing need statements. The

first two gllidelines are fundamental and are critical to effective translation; the

remaining three guidelines ensure consistency of phrasing and style among team

mernbers, Exhibit 7 provides exarnples to iIlu strate each guideline.

Express tite need in terms of what the product has to do, not in terms of how it

might do it. Customers express their preferertces by describing a solu-

44 PRODUCT DESIGN AND DEVE LOPMENT

Cn, ..srnan Model A3

8

Interviewer(s): Jonathan and Lisa

Date: 19 December 1994

CUirenily uses:

f

Bill Esposito

10C Memorial Orive

Cambridqe, MA 02139

617- 864-1274

Customer:

Address:

Telephone:

Willing to do Type o user: uilding rnaintenance

follow-up? ves

Qucstion/Prompt Customer Statement Interpreted Need

Typi cai uses I need to drive screws fast, The SO dr ives screws faster

i

fast er lhan by hand . lhan by hand .

I sometimes do ducl work; use The SO drives sheet metal

sheel metal screws. screws into metal duct work.

A 101 of eleclrical : switch covers, The SO can be used lar

outl ets, fans, kilchen appliances. screws on eleclrical devices.

Likes-currenl tool I like lhe pistol grip; it leels the The SO is comfortable to grip.

bes!.

I

I like lhe magnetized lip. The SO lip retains lhe screw

I belore JI is driven,

Oislikes-currenl 1001 I don't Iike il when lhe tip slips The SO lip remains aligned

I

off the screw. wilh lhe screw head wthout :

slipping.

I would like lo be able lo lock il The user can apply torque

so I can use il wilh a dead manually lo lhe SO lo drive a

!

battery. screw.

I

Can't drive screws into hard The SO can drive screws into

I

wood. hard wood.

i

Sometimes I strip tough screws. The SO does not slrip screw

. heads,

Suggested An attachment to allow me to The SO can access screws at I

improvements reach down skinny hales . the end al deep, narrow hales. l'

A point so lean scrape paint off The SO allows the user to

I

al screws. wor k with screws that have

i

been painled over.

Would be nice jI it could punch The SO can be used to creal e \

a pilot hale. a pilol hale.

EXHIBIT 6 Customer data template filled in with sample customer statements and interpreted needs. SO is

an abbreviation lar screwdriver. (Note thal this template represents a part ial Iist lrom a single

interview. A typical interview session may elicit more than 50 customer statemenls and nter-

preted needs.)

CHAPTER 3: IDENTIFYING CIJSTOMER N!::EDS 45

Guideline Customer Statement Need Statement-Right Need Statement--Wrong

"What" not "how' "Why don't you pul The screwdriver battery is The screwdriver battery

protective snields around Ihe protected trorn accidental contacte are covered by a

batery contacs?' shortinq. piastic slidng door.

speclclty "1 drop my screwdriver ail TI:8 screwdriver operales The screwdriver is rugged.

Ihe time" normally atter repealed

droppinq.

Positive not "il doesn't matter il it's The screwdriver operales The screwdriver is nol

negative raining, I slill need lo work normally in Ihe rain. disabled by Ihe rain.

outside on Salurdays."

An attribute of the "l'd Iike lo charge my battery The screwdriver battery can An automobile cigarette

product trom my cigarette lighler." be charged frorn an lighler adapler can charge

autornobile cigarette lighler. Ihe screwdriver battery.

Avoid "must" and "1 hale it when I don't know The screwdriver provides an The screwdriver should

"should" how much juice is left in Ihe indicalion 01 Ihe energy level provide an indication 01Ihe

batteries 01my cordless 01 Ihe battery. energy level 01Ihe battery.

lools."

EXHIBIT 7 Examples illustratinq the guidelines lar wriling need statements.

tion concept 01' an implementation approach; however, the need statement

should be expressed in terms independent of a particular technological

solution.

Express the need as specifically as the raw data. Needs can be expressed at

many different levels of detail. To avoid loss of information, express the

need at the same level of detail as the raw data.

Use positive, not negative, phrasing. Subsequent translation of a need into a

product specification is easier if the need is expressed as a positive state-

mento This is pot a rigid guideline, because sometimes positive phrasing is

difficult and awkward. For example, one of the need statements in Exhibit

6 is "the screwdriver does not strip screw heads." This need is more natu-

rally expressed in a negative formo

Express the need as an attribute of the producto Wording needs as statements

about the product ensures consistency and facilitates subsequent transla-

tion into product specifications. Not all needs can he cleanlv expressed as

auributes of the product, however, and in most 01 these cases the needs can

be expressed as attributes of the user of the product (e.g., "the user can

apply torque manually to the screwdriver to drive a screw") .

Avoid the words must and should. The words must and should imply a level of

importance for the need. Rather than casually assigning a binary impor-

tance rating (must versus should) to the needs at this point, we recommend

deferring the assessment of the importance of each need until step 5.

46 PRODUCT DFSIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

The !ist of custorner needs is the superset of all thc needs elicitee! frorn all the

interviewed customcrs in th e target market. Sorne of th ese needs my be con-

tradictory. Sorne needs may not be technologi cally realizable. The cons train ts of

te chn ical and ecunumic feasibility are inc. 'pora ted into the pruccss of estab-

lishing product specifications in subsequent developmeru st cps. (See the chap-

ter "Esta blishing Product Specifica tions.")

STEP 4: ORGANIZE THE NEEDS INTO A HIERARCHY

The result of ste ps 1 through 3 should be a list of 50 to 300 n eed statements.

Such a large number of detailed needs is awkward to work with and difficult to

summarize for use in subsequen t development activities, The goal of step 4 is to

organ ize these needs into a hierarchical list, The list will typically consist of a set

uf primary needs, eac h one of whi ch will be further characterized by a set uf sec-

o ndary needs. In cas es of very co mplex products, the secondary needs may be

broken down into tertiary needs as weIl . The primary needs are the most gener-

al needs, while the secondary and tertiary needs express needs in more deta il.

Exhibit 8 shows the resulting hierarchical list of needs for the screwdriver exam-

pIe . For th e scrcwdriver, there are 15 primary needs and 49 secondary needs.

Note that two of the primary needs have no associated secondary needs.

The procedure for organizing the needs in to a hierarchical list is intuitive,

and many teams can successfully comple te th e task without detailed instructions.

For cornpleteness, we provide a step-by-step procedure here. This activity is best

performed on a large table by a group of six 01' fewer team mernbers.

1 Print or write each need statement on a separate card or selfstick note. (A print

macro can be easily written to print th e need statements directl y frorn th e

data template. A nice feature of thi s approach is that the need can be print-

ed in a large font in the center of the card and then the original custorner

statement and other relevant information can be printed in a smaIl font at

the bottom of th e card for easy reference. Four "cards " can be cut frorn a

standard printed sheet.)

2 Eliminate redundant statements. Those cards expressing redundant need

statements can be stapled together and treated as a single cardo Be careful

to consolidate only th ose staternents th at are identical in meaning.

3 Group the cards according to the similarity ofthe needs they exprese. At thi s point,

ihc team sh ould ~ l L t e m p t to crea re groups uf roughly th ree tu sevcn cards

that express similar needs. The logic by which groups are created deserves

special attention. Novice development teams often create groups according

to a technological perspective, c1ustering needs relating to, for example,

rnaterials, packaging, or power. 01', they create groups according to

assumed physical components such as enclosure, bits, switch, and battery.

Both of th ese approaches are dangerous. RecaIl that the goal of the process

is to creare a description of the needs of the customer. For this reason, the

groupings should be con sisten t with the way customers think about their

CHAPTER 3: IDENTIFYING C U S T O M ~ R NEE DS 47

The SO provides plenty of power to drlve screws.

3 l il e SO maintains power tor several hours 01 heavy

use

3 Trie sr) can drive s 3'1.'S into hardwood.

The SD drives sheet metal screws int o metal ducl

work.

The SO drives screws Iaster than by hand.

The SO makes it easy to start a s::rew.

3 l he SO retains the screw bele re it is driven.

3 The SO can be used to create a pilot hale.

The SO works with a variety of screws.

4 The SO can lu rn ohillips, torx, socket, and hex

head screws.

4 l he SO can turn rnany sizes 01 screws .

The SD can access most screws.

Tne SO can be maneuvered in li ghl areas .

4 The SO can access screws al the end 01 deep,

narrow holes.

The SO turns screws that are in poor condition.

The SO can be used l o remove grease and di rt lrom

screws.

The SO allows the user l o war k wilh painled screws.

The SO feels good in the user's hand.

The SO is comlortabl e when the user pushes on it.

The SO is coml ortable when the user resists

Iwisl ing.

The SO is balanced in Ihe user' s hand.

The SO is equally easy l o use in righl or left hands.

The SO weighl is jusI righ!.

2 The SO is warm to touch in cold weal her.

lhe SO remaips comlortable when left in Ihe sun.

The SO is easy to control while turning screws.

The user can easily push on the SO.

The user can easily resist the SO twisting.

2 The SO can be locked " on."

4 The SO speed can be controlled by the user while

turning a screw.

The SO remains aligned wit h the screw head

without slipping.

The user can easily see where the screw is.

The SO does not strip screw heads.

The SO is easi ly reve rsible.

The SO is easy to set-up and use.

The SO is easy to turn en.

i he SD prevente inadvcrtent swilcn ing ol f.

3 The mximum torqu e 01 tn SO can be set by

l he user .

Th8 SD provides ready access to bits or

access ories .

The SO can be attached to the user la r l emporary

slorage.

The SO power is convenient.

The SO is easy to reeharge.

3 The SO can be used while recharging.

5 lhe SO recharges qui ckly.

2 The SO batt eries are ready to use when new.

The user can apply torque manually lo lhe SO l o

drive a screw.

The SO lasts a long time.

The SO tip survives heavy use.

2 The SO can be hammered.

The SO can be dropped Irom a ladder withoul

damage.

The SO is easy to store.

The SO l its in a toolbox easily.

The SO can be charged whil e in storage.

2 The SO resist s corr osion when left outside or in

damp places .

3 The SO mai ntains its charge after long periods

01 storage.

The SO maintains its charge when we!.

The SO prevents damage to the work.

The SO prevenls damage l o the screw head .

The SO prevenls scral ching 01 l inished surlaces.

3 The SO has a pleasant sound when in use.

The SO looks Iike a professional quallty tool.

The SO is safe.

The SO can be used on electrical devices.

The SO does not cut Ihe user 's hands.

EXHIBIT 8 Hierarehicallist 01primary and seeondary customer needs lor the eordless screwdriver. Impor-

tance ral ings are shown lar some 01Ihe needs (using the ranking seheme given in Exhibil 9).

necds and not with the way th e development team thinks about the prod-

uct. Thc groups should correspond to necds customers would vicw as sirni-

lar. In fact, sorne practitioners argue that cus to mers should be th e ones to

organize the need staterne nts.

48 PRODUCT DESIGN AND DEVEI.OPMENT

4 For each group, choosea label. The label is itself a statement of need that gen-

eralizes all of the needs in the group. It can be selected frorn one of the

needs in lhe group, 01' lile team can write a new need statement.

:> e.nsider creating "supergroups" consisting of tuio to five groups. If there are

fewer than 20 grOLlps, ihen a two-level hierarchy is probablv snfficicnt lo

organize the dala. In this case, the group labels are primal)' needs ami the

grcmp ruernbers are seconrlary needs. However, if there are more than 20

groups, th e team may consider creating sllpergroups, and therefore a third

level in the hierarchy. The process of creating supergroups is identical lo

the process of creating grollps. As with the previous stcp, cluster groups

according lo similarity of th e need they express and then creare or select a

supergroup labe!. These sllpergroup labels become the primary needs, the

group labels become the secondary needs, and the mernbers of the grollps

become tertiary needs.

6 Review ami edil the organized needs statements. The arrangement of needs in

a hierarchy is not unique in terrns of being "correct." Al this poinl, the team

may wish to consider alternative groupings or labels.

STEP 5: ESTABLlSH THE RELATIVE IMPORTANCE OF THE NEEDS

The hierarchical list of needs does not provide any information on the relative

importance that customers place on different needs. Yet the development team

will have lo make trade-offs and allocate resources in designing the product. A

sense of the relative importance of the various needs is essential to making these

trade-offs correctIy. Step 5 in the needs process establishes the relative impar-

tance of the customer needs identified in steps 1 through 4. The outeome of this

step is a numerical importanee weighting for a subset of the needs. There are

lWO basic approaches to the task: (1) relying on the consensus of the team mem-

bers based on their experience with customers, or (2) basing the importanee

assessment on further customer surveys. The obvious trade-off between the two

approaches is cost versus accuracy: the team can make an educated assessment

of the relative importance of the needs in one meeting, while a customer survey

takes a minimum of two weeks and more realistically one or two months. In gen-

eral, we believe the custorner survey is important and worth the time required lo

eomple te it. Other development tasks, such as concept generation and analysis

of cornpe titive products, can hcgin before the relativc importance survevs are

complete.

The team should at this point have developed a rapport with a group of CllS-

tomers. These same customers can be surveyed to rate the relative importance of

the needs. The survey can be done in person, by telephone, or by mai!. Few CllS-

tomers will respond to a survey asking them to evaluate the importance of 100

needs, so typically the team will work with only a subset of the needs. A practical

limit on how many needs can be addressed in a customer survey is 20 to 30. This

limitation is not too severe, however, becausc many of the needs are either obvi-

CHAPTER 3 : D ENT I FY I NG C UST OME R NEEDS 49

Cordless Screwdriver Survey

Fcr eac h 01 ol lowi : screwdriver teat ures. please indicats en scale 01 I l o 5 hQW

import an: the tsat ure is lO YOIJ. h ease use the lollcwi ng sca!e:

1. Feature is undesirable. I would not ccnsider 3 product with this l eal ure.

2. Fealure is nol irnport ant , but I would not rnmd havinq it

3. Feature would be nice lo have, bul is nol uec essar y.

4. Fealure is highly desirable, but I would consider a product without it.

5. Fea!ure is critica! I would no! consider a product wilhout this leature.

_ _ _ _ The screwdriver can drive screws into hardwo od.

___ _ The screwdriver can turn phillips, torx, soc ket , and hex head screws .

___ _ The screwdriver can acce ss screws al lhe end 01dee p, narrow holes.

And so forth.

EXHIBIT 9 Example importance survey (partial).

o us ly irnportant (e .g., th e uscr ca n easily se e wh er e the screw is) or a re eas)' lo

imple rnent (e .g. , thc screwd rive r prevcnts in advertent switc h in g off) . The te am

ca n therefore lirni t th e scope o f the su l've)' by o n ly querying customers abou t

ne ecls th at are likely lo give rise to d ifficult te chnologi cal trade-offs or costl y fe a-

tu res in th e p roduct d esigno Such n eeds wo u lcl inclucle th e ne ed lO val')' speed,

th e n cecl lO drive sc rcws in to hardwood, and th e nc ed lo have rhe scre wd ri ve r

c rn it a pl easant souncl . Alternatively th e team cou lcl c1evel op a se t 01' sul'veys lo

as k a va riety 01' cus io mers each about d ifferen t su bse ts 01' th e needs list. There

a re many su rvey e1esigns fo r cs tablishi ng th e rel ative impo rtan ce 01' custome r

ne ecls. One good c1esign is illu strated by the portion of the corclless screwdriver

su rve y shown in Exhibit 9.

The surve y responses for each ne ed state rne n t ca n be characte r ized in a vari-

e ty of ways: by the mean, by sta nd a rd dcviat io n , o r by th e numbe r 01' respo nses

in each ca tegory. The responses ca n then be use el lo ass ign an importance

we ighling lo th e need sta te me n ts. T h e sa me scale of 1 lo 5 ca n be used lO SU Ill-

marize th e irnportancc elat a, So rn e ofrhe nceds in Exhibir Hare wci ghted ac cord-

in g lo th c su rvev d at a.

srEP 6: REFLECT ON THE RESULTS AND THE PROCESS

The final ste p in the methodology is to r efl ect on the resu lts ancl the process.

While the process o f id entifying customer needs ca n be usefully st ructu r ed, it is

not a sci ence. The team must continually challenge its r esults to vcrify that they

are consistent with the knowl edge and intuition the team has devel oped th rough

many hours a l' inte racti on with custo rne rs . Some questi ons lo ask include:

SUMMARV

SO PROOUCT OESIGN ANO OEVELOPMENT

Have we interact ed with aIl of the important typt:s of cus tomers in our tar-

get ma rke t?

Ar e we abl e to see beY011d needs related on!y to existing products in o rder

to ca plm-e the Iatent ne c ' ,'; of o ur target c us torncrs ?

Ar e th ere al eas of inq uiry we should pursue in Iollow-up interviews ol' su r-

veys?

Wh ich o f the custo me rs we spoke to would be good parti cipants in o u r o n-

going development efforts?

Wh at do we know I ~ O W th at we didn' t kn ow when we star ted? Are we su r-

prised by a ny of th e needs?

Did we invol ve everyone within our own o rgani za tion who needs to d eepl y

understand custorner needs?

How might we irnprove the p rocess in futu re cfforts?

Id entifying custome r needs is an integral pan ofthe concep t d evel opment phase

of the product development process. The resulting cus to mer n eeds are us ed to

guidc the team in establish ing product specificatio ns , ge ncr ati ng product co n-

ce pts, and sc1ec ting a p r oduct concept for further d evel opment.

The process of identifying customcr needs inc1udes six st eps:

1 Define the scope of the product development effor t,

2 Ga ther raw d ata fr o m customers.

3 Interpret the raw dala in terms 01" customer needs,

4 Organize th e necds into a hi era rchy of prirnary , secon dary, a nd tertiary

needs.

5 Establish the rel ative importancc of the needs.

6 Reflect on the r esults and the process.

Creating a high-quality infor matio n channc1 fr om custo me rs to the product

developers ensures that those who directly control the details of the prod-

uct, inc1uding the product designers, fuIl y understand the needs o f the cus-

tomer.

Lead users a re a good so urce of custo mer needs bec ause th ey experience

IH'W n ccds mo nt h s or ye ars uhc.id o f t he hulk o f th markctpl acc a nd

because they stand lo benefit substantially from new product innovations.

Furthermore , they are frequently able to articulate their needs more clear-

ly than typical custo mers.

Latent needs are fr equently as important as explicit needs in determining

cus tomer satisfacti on. Latent needs are those that many customers recog-

nize as important in a final product but do not or are not able to articula te

in advance .

CHAPTER 3: IDENT IFYING CUSTOMER NEI::DS 51

Cus tn me r n eeds should he expr essed in tcrms of wh at th e product h as to

do, not in terms o f how rhc p roduct mi ght he implernented . Ad hcrcncc to

thi s principle lcaves rhe dcvel opment team with maxirnurn lexibili ty to ~ e n

U " c a nd scl cct produrt co nccp ts.

~ T he key bencfi ts of th e methodology are: ens uri ng t hat th c pi oducr is

ocused on custorn er nceds a no th a l no critica ! cu si omcr ueed is fo rgoueu:

d evcloping a clca r underst anding alilong mcuibcrs 01" th e dcvclopmeru

tc am 01" the n ecds of the cus to mcrs in th e largel marke t: d eveloping a fact

bas e to be us ed in generating con cep ts, sel e cting a product concept, a n d

es ta blish ing product spccificati ons; and crcati ng an archiva] record of th e

n eeds phase of th e developmcnt process.

REFERENCE5 AND BIBLlOGRAPHY

Con cept ('//gi l/f'ering IS a methodol ogy devel oped by rhe Ce nter for Quality

Manag crn cnt. This chapter benefits frorn our observations of th e development and

appli cariou of concepl engineering. For a complet e and detail ed description of con-

cept e ngine ering, see:

Burehill, Gary, et al., Concept Engineering: Th e Key to Operationall Defining Your

Customer's Requ irements, Cerner for Quality Managernent, Cambr idge, MA,

Document No. 71, September 1992 .

The research by Griffin and Hauser is only one of th e rigorous efforts to validate dif-

ferent methods for extracti ng needs fr om intervi ew data. Their study of the fra ction

of needs identified as a furiction of the nurnber of cus tomers intervi ewed is parti cu-

larly interesting.

Gr iffin , Abbie, and John R. Hauser, "The Voice of the Cus to mer," Marketing

Scienre, Vol. 12, No . 1, Winter 1993 .

Kinnear and Taylor th oroughly di scuss data colle cti on methods and survey design in:

Kinnear, Thomas e., and j ames R. Taylor, Marketing Research: An Applied Approach,

MeGraw-HiU, New York, NY, 1991. ISBN 0-07-034757-3.

Payne ' s book is a detailcd and interesting discussion of how to pose questions in sur-

veys.

Payne, Stanley L. , The A ,.t o/ Asking QlII'StiOIl S, Princeton University Press,

Princet on, N.T, 1951.

Tor al qualir v man agenwnl (TQ\f) providr-s a valua ble- pe-rspr-cr iv on ho\\" idenrifv-

ing cus to mer needs fits into an overall c fort LO improve the quality of gaods and se r-

VIces .

Shiba, Shoji, Ajan Craham, and David Walden, A NeioAmmcan TQM: Four Pra ctical

Reuolutions in Management, Produetivity Press, Cambridge, MA, and The Center for

Quality Managernent, Cambridge , MA, 1993. ISBN 1-56327-032-3.

Urban and Hauser provide a thorough discussion of how to ereate hierarehies of

needs (along with many other tapi es) .

52 PRODUCT DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

Urban, Cien L., andjohn R. Hauser, Design and Marketing o/ Neui Products, second

ed itio n, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1993. ISBN 0-13-201567-6.

\'on Hippei describes many years of research on the rol e of lead users in innovaiion.

He provides uscul guideiines for idcntifying' lead users.

von Hippel, Eri , The Sources o/Innouation, Oxord University Prcss, Nev.. York, NY,

i 988. ISBN 0- 19-504085-6.

EXERCISES

Translate the following customer statements about a studen t book bag into prop-

er needs statements:

a "See how the leather on the bottom of the bag is all scratched; it's ugly."

b "Wh en I'm st anding in line at the cashier trying to find my checkbook while

balancing my bag on my kn ee, I feel like a stork."

e "This bag is my life ; ifl lose it I'm in big trouble."

d "Theres nothing worse than a banana that's been squished by the edge ofa

textbook. "

e "1 never use both straps on my knapsack; 1just sling it over one shoulder."

2 Using a camera, document user frustration with an everyday task of your own

choice.

3 Choose a product that continually annoys you. Identify the needs the developers

of this product missed. Why do you think these needs were not met? Do you think

the developers deliberately ignored these needs?

THOUGHT aUESTIONS

1 How would the needs methodology change if a development team wished to pur-

sue two very different market segments with the same product?

2 One of the reasons the methodology is effective is that it involves the entire devel-

opment team. Unfortunately, the methodology can beeome unwieldy with a team

of more than six people. How might yo u modify the methodology to maximize

involvement yet maintain a focused and decisive effort given a development team

of 12 or more people?

3 Can the process of identifying customer needs lead to the creation of innovative

produet eoncepts? In what ways? Could a struetured process of identifying cus-

torner needs lead to a fundament alIy new product concept like the Post-It note?

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- TM11-5855-213-23&P - AN-PVS4 - UNIT AND DIRECT SUPPORT MAINTENANCE MANUAL - 1 - June - 1993Документ110 страницTM11-5855-213-23&P - AN-PVS4 - UNIT AND DIRECT SUPPORT MAINTENANCE MANUAL - 1 - June - 1993hodhodhodsribd100% (1)

- Heat TransgerДокумент56 страницHeat TransgerShusha Shomali67% (3)

- Lesson 3 Fold Mountains Task SheetДокумент2 страницыLesson 3 Fold Mountains Task Sheetapi-354360237Оценок пока нет

- XY Model Symmetric (Broken) Phase Normal (Supercon-Ducting) PhaseДокумент12 страницXY Model Symmetric (Broken) Phase Normal (Supercon-Ducting) PhaseKay WuОценок пока нет

- Chapter 5 - Launch Vehicle Guidance Present Scenario and Future TrendsДокумент20 страницChapter 5 - Launch Vehicle Guidance Present Scenario and Future TrendsAdrian ToaderОценок пока нет

- WMA11 01 Que 20190109Документ28 страницWMA11 01 Que 20190109tassu67% (3)

- PFI ES-27-1994 - Visual Examination - The Purpose, Meaning and Limitation of The TermДокумент4 страницыPFI ES-27-1994 - Visual Examination - The Purpose, Meaning and Limitation of The TermThao NguyenОценок пока нет

- NSCP 2015Документ1 032 страницыNSCP 2015Rouzurin Ross100% (1)

- Ridpath History of The United StatesДокумент437 страницRidpath History of The United StatesJohn StrohlОценок пока нет

- Anxiety in Practicing English Language As A Means of Communication in Esl ClassroomДокумент40 страницAnxiety in Practicing English Language As A Means of Communication in Esl Classroomkirovdust100% (1)

- Acta Scientiarum. Biological Sciences 1679-9283: Issn: Eduem@Документ12 страницActa Scientiarum. Biological Sciences 1679-9283: Issn: Eduem@paco jonesОценок пока нет

- ODI Case Study Financial Data Model TransformationДокумент40 страницODI Case Study Financial Data Model TransformationAmit Sharma100% (1)

- Data Mining Chapter3 0Документ32 страницыData Mining Chapter3 0silwalprabinОценок пока нет

- Ielts Writing Key Assessment CriteriaДокумент4 страницыIelts Writing Key Assessment CriteriaBila TranОценок пока нет

- I S Eniso3834-5-2015Документ24 страницыI S Eniso3834-5-2015Ngoc BangОценок пока нет

- Theatre at HierapolisДокумент7 страницTheatre at HierapolisrabolaОценок пока нет

- Hospital Information SystemДокумент2 страницыHospital Information SystemManpreetaaОценок пока нет

- Electric CircuitsДокумент546 страницElectric CircuitsRAGHU_RAGHU100% (7)

- HealthSafety Booklet PDFДокумент29 страницHealthSafety Booklet PDFAnonymous VQaagfrQIОценок пока нет

- Grade 6 Mathematics Week 12 Lesson 4 - 2021 - Term 2Документ6 страницGrade 6 Mathematics Week 12 Lesson 4 - 2021 - Term 2MARK DEFREITASОценок пока нет

- Western Oregon University: CSE 617 Open Source ToolsДокумент5 страницWestern Oregon University: CSE 617 Open Source ToolszobelgbОценок пока нет

- Art and Design - Course ProspectusДокумент20 страницArt and Design - Course ProspectusNHCollegeОценок пока нет

- MCQ TEST For Mba 1st Year StudentДокумент10 страницMCQ TEST For Mba 1st Year StudentGirish ChouguleОценок пока нет

- Bei 076 III II AntenamarksДокумент8 страницBei 076 III II Antenamarksshankar bhandariОценок пока нет

- Chapter 9Документ52 страницыChapter 9Navian NadeemОценок пока нет

- DW Basic + UnixДокумент31 страницаDW Basic + UnixbabjeereddyОценок пока нет

- 6th STD Balbharti English Textbook PDFДокумент116 страниц6th STD Balbharti English Textbook PDFꜱᴀꜰᴡᴀɴ ꜱᴋОценок пока нет

- Literature SurveyДокумент6 страницLiterature SurveyAnonymous j0aO95fgОценок пока нет

- MM 321 Field ReportДокумент15 страницMM 321 Field ReportSiddhant Vishal Chand0% (1)