Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Accounting Irregularities, Management

Загружено:

Dr.Hira EmanИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Accounting Irregularities, Management

Загружено:

Dr.Hira EmanАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

F. A. Elayanand Finance ORIGINALet al./Accounting and Finance XXX Journal The UK 1467-629x 0810-5391 Accounting ARTICLES ACFI Authors Oxford, compilation 2008 Blackwell Publishing Ltd AFAANZ

Accounting irregularities, management compensation structure and information asymmetry

Fayez A. Elayana, Jingyu Lia, Thomas O. Meyerb

a

Department of Accounting, Faculty of Business, Brock University, St. Catharines, L2S 3A1, Canada b Department of Marketing and Finance, College of Business, Southeastern Louisiana University, Hammond, 70402, USA

Abstract The discovery of accounting irregularities is an important negative event for a company. The restatement resulting from the irregularity represents an average of 364 per cent of net income for the 152-rm sample and the irregularities are predominantly revenue enhancing. The irregularity rms exhibit both lower transparency and visibility compared to a matched sample of non-irregularity rms. Furthermore, prior to the announcement, these rms experienced poorer operating performance and their executive compensation structure is found to be signicantly more equity-based. Therefore, rms that have greater opportunity and incentive are shown to be more likely to commit accounting irregularities. Key words: Accounting irregularities; Accounting errors; Restatements; Executive compensation structure JEL classication: G3, G14, J33, M41, M52 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-629x.2008.00266.x

1. Introduction Properly functioning capital markets require reliable and relevant accounting and nancial information as a basis for allocating capital and other scarce

The authors wish to thank Rick Boebel, Steven Cahan, Brian Murphy, Ramesh Rao, Lawrence Rose, John Thornton, Robert Faff (the Editor), Ian Zimmer (the Deputy Editor) and Julie Cotter (the referee), as well as participants at the 7th New Zealand Finance Colloquium, the 2003 Academy of Financial Services, Financial Management Association, European FMA, and European Applied Business Research conferences, and a Departmental Seminar at Southeastern Louisiana University for helpful comments. The research assistance provided by Jie Lian is gratefully acknowledged. Received 18 July 2007; accepted 25 January 2008 by Ian Zimmer (Deputy Editor).

The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

742

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

resources. However, reports of accounting irregularities (AIs) in the wake of notorious business failures like Enron and WorldCom and disclosures of similar problems at other large rms have caused a great deal of concern over the issue of nancial statement reliability and the impact on shareholders, the corporate sector and the general economy.1 Understanding the underlying circumstances and motives that gave rise to these AIs is important and a necessary precursor to effectively prevent future occurrences. Although many have suggested that the explanation is related to the level and the structure of management compensation (the percentage of equity-based compensation including options relative to total compensation) as well as to executive private benets, the explanation is subject to a great deal of debate. This issue has captured the attention of the media, investors, government regulators and legislators and has also prompted US president George W. Bush to form the Corporate Fraud Task Force and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to form the Public Oversight Boards Panel on Audit Effectiveness (Ofce of the Press Secretary, 2002). In fact, former SEC Chairman Arthur Levitt testied: It is therefore not enough that nancial statements be accurate, the public must also perceive them as being accurate . . . In recent years, countless investors have suffered signicant losses as market capitalizations have dropped by billions of dollars due to restatements of audited nancial statements (Levitt, 2000, emphasis in the original). The connection between the structure of management compensation and management incentives is an unresolved issue. Several studies (Hemmelberg et al. 1999; Rajgopal and Shevlin, 2002; Hanlon et al., 2003) provide evidence that is consistent with a positive incentive alignment view of equity compensation, including stock options. In contrast, other studies argue negatively that options are an inefcient way to compensate managers (Meulbroek, 2001; Hall and Murphy, 2002) or that stock options do not exhibit an empirical relation consistent with the economic motives behind granting them. Furthermore, Bar-Gill and Bebchuk (2003) and Goldman and Slezak (2006) show that performancebased compensation can induce managers to misreport performance. Jensen (2003) asserts that non-linearity in pay-for-performance systems induces managers to lie and that such is so pervasive that rms would be better off adopting solely linear pay-for-performance systems. The arguments against incentive alignment are that, rst, the convexity of options gives managers the incentive

1

The Statement on Auditing Standards No. 53 (The Auditors Responsibility to Detect and Report Errors and Irregularities) denes accounting irregularities as intentional misstatements or omissions of amounts or disclosure in nancial statements. Irregularities might include fraudulent nancial reporting undertaken to render nancial statements misleading and misappropriation of assets. Conversely, accounting errors refer to unintentional misstatements or omissions of amounts or disclosures in nancial statements. Examples of accounting errors might involve mistakes in gathering or processing accounting data from which nancial statements are prepared. The main difference between accounting errors and accounting irregularities hinges on the intention of the misstatements.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

743

to take excessive risk. Second, the usefulness of stock options as incentive devices is mitigated by their limited downside risk and the tendency of companies to reprice underwater options. Finally, the options give managers the incentive to fraudulently manipulate the companys stock price to enhance their value. Therefore, the current theoretical and empirical evidence raises the possibility that the perceived increase in AIs might be a result of the structure of management compensation. Indeed, this possibility seems to have become accepted wisdom among policy-makers and regulators. For example, Alan Greenspan, the former Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, on 16 July 2002, speculated about the causes of AIs as follows: Too many corporate executives sought ways to harvest some of those stock market gains. As a result, the highly desirable spread of shareholding and options among business managers perversely created incentives to articially inate reported earnings in order to keep stock prices high and rising.2 Hence, the purpose of the present paper is to examine whether the empirical evidence supports the claim that an incentive-based compensation structure is positively associated with the probability of AIs.3 The principal objectives of this research are threefold. The rst objective is to establish that the restatement of income resulting from the irregularity represents a large economic loss to the rm. The second objective is to examine the types of irregularities committed to determine what impact they would have on the rm.4 The third objective is to show why the executives at the irregularity companies become involved in these activities in the rst place and identify factors that lead them to believe that they could get away with their illegal actions. This is accomplished through a statistical comparison of rms that committed AIs to a matched sample of non-irregularity rms. The amount of the average restatement equals 363.5 per cent of net income and this suggests that the irregularities were committed to disguise signicant losses. The matching sample analysis reveals that irregularity rms have signicantly more volatile stock prices, are followed by signicantly fewer stock analysts and are relatively smaller in size. Therefore, these attributes suggest that the irregularity rms have both greater information asymmetry and are less visible. Irregularity rms are also found to exhibit poorer performance prior to the irregularity announcement. Furthermore, the top executives at the AI rms are shown to receive a relatively large percentage of their pay package in the

Alan Greenspans testimony before the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, 16 July 2002. Typical compensation schemes consist of largely xed, annual compensation (representing level) and long-term, incentive-based components (indicating structure).

The discovery of AIs has serious implications; the company might face shareholder classaction litigation, investigation by the SEC, a criminal investigation, and/or management dismissal. In the case of accounting errors, the company can typically restate previous nancial reports without any legal implications.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

744

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

form of equity-based compensation. The types of irregularities committed are predominantly described in the announcements as being overstatements of revenue, income or prot, early recognition of income, phantom sales and overstating assets. As the effect of these irregularities are revenue enhancing, the ndings regarding rm performance and compensation structure provide a link that goes directly to the motive for commission of these illegal acts. In a criminal trial, motive and opportunity are established to support evidence of guilt. In this research, information asymmetry (opportunity) is linked to poor performance and management compensation structure (motive) as an explanation for the commission of AIs (guilt). The outline of the research follows. Section 2 presents a review of the literature. The testable hypotheses are developed in Section 3. The data used and the methods of analysis are described in Section 4. Section 5 provides the empirical results. Finally, Section 6 presents a summary of the research and conclusions. 2. Review of the literature Although there are no studies that directly link the level and structure of management compensation to AIs, a large number of studies provide evidence about the linkage between management compensation and earnings management or manipulation (see e.g. Healy, 1985; Dye, 1988; Elitzur and Yaari, 1995; Holthausen et al., 1995; Healy and Wahlen, 1999; Duru and Iyengar, 2001; Klinger et al., 2002).5 In general, these studies conclude that when management compensation is based on accounting-based performance measures, management has incentive to manage and manipulate accounting earnings to maximize their own benets. Another group of studies (see Trueman and Titman, 1988; Richardson, 2000) examine the relationship between earnings management and information asymmetry. They conclude that managements informational advantage is the principal factor leading to earnings management. Therefore, an asymmetric information environment is an essential prerequisite for earnings management. Closer in context to this study is a group of studies that examine the characteristics of rms involved in fraud and restatements. Defond and Jiambalvo (1991) use a sample of 41 annual overstatement errors from 1977 to 1988 to compare characteristics of restatement and non-restatement companies. They propose that management overstates earnings to maximize their compensation and to avoid violation of debt covenants. They nd that companies with restatements are less likely to have audit committees, and have diffuse ownership and

5

In this research, total compensation is the sum of annual compensation and long-term incentive compensation. Annual compensation includes salary, bonuses and other annual compensation (perquisites and tax payment reimbursements). Long-term incentive compensation includes restricted stock awards, stock options, stock appreciation rights, long-term incentive plan payouts and all others.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

745

relatively fewer income-increasing Generally Accepted Accounting Principle alternatives. Earnings growth and overstatements are also found to be negatively correlated. Erickson et al. (2006a) compare executive equity incentives of 50 rms accused by the SEC of accounting fraud during the period of 19962003 with two samples of rms not accused of fraud. They nd no evidence to support the argument that equity incentives are associated with fraud. In contrast, Denis et al. (2005) report a signicant positive association between the likelihood of securities fraud being alleged and a measure of executive stock option incentive. This supports the assertions made by policy-makers that incentives from stock-based compensation and the resulting equity holdings increase the likelihood of fraud. Erickson et al. (2006b) examine whether rms pay additional income taxes on allegedly fraudulent earnings. Their sample consists of rms that restated their nancial statements in conjunction with SEC allegations of accounting fraud during the years 19962002. They nd that the mean amount that rms sacriced is 11 cents in additional income taxes per dollar of inated pretax earnings. Their analysis suggests that rms are willing to sacrice substantial cash to inate their accounting earnings. 3. Development of testable hypotheses 3.1. Information asymmetry hypothesis Previous research points to the existence of information asymmetry between management and investors. Dye (1988) and Trueman and Titman (1988) suggest that information asymmetry is a necessary and sufcient environmental condition for earnings management to occur. Richardson (2000) nds that there is a systematic, positive relationship between the level of earnings management and the level of information asymmetry. Under the assumption that AIs represent an aggressive form of earnings management (although this is an understatement because, in most cases, involvement in AIs is illegal) the implication of the above research is that rms with higher levels of information asymmetry are more likely to engage aggressively in earnings manipulation. H1: Firms characterized as having greater levels of information asymmetry are more likely to commit accounting irregularities. 3.2. Management compensation hypothesis Management compensation plans are designed to motivate management to improve the rms performance and to align the interests of management with those of shareholders. Jensen and Meckling (1976) argue that as long as the management team owns less than 100 per cent of the company, they have incentives to maximize their own wealth at the expense of shareholders. The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

746

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

Prior research provides evidence that management compensation is explicitly or implicitly linked with accounting data (Duru and Iyengar, 2001), and as long as accounting data are used in compensation contracts, incentives can arise to manage the data to maximize management welfare (Dye, 1988). The earnings management literature provides evidence that management manipulates accruals and inventory to maximize their own compensation (see e.g. Healy, 1985; Gaver et al., 1995; Holthausen et al., 1995). Additionally, Klinger et al., (2002) nd that chief executive ofcers (CEOs) in 23 companies involved in AIs earned 70 per cent more than the typical CEO at a larger company. They conclude that rather than aligning the interests of executives and investors as promised, CEO pay packages bloated by stock options led to ever more aggressive accounting techniques, making many companys earnings statements works of ction masquerading as fact(p. 3). Abowd and Kaplan (1999) suggest that total compensation measures the level of compensation and determine where the manager works, while long-term incentive compensation determines how management works. Jensen and Murphy (1990) emphasize the importance of long-term incentives as a determinant of rm performance. Mehran (1995), Main et al. (1996) and McKnight and Tomkins (1999) nd that rm performance is positively related to the percentage of executive compensation that is equity based. Therefore, managements desire to increase either their total or long-term incentive compensation serves as a motive for committing revenue-enhancing AIs. Therefore, the general hypothesis with regard to management compensation is stated as follows: H2: Firms having a greater proportion of equity-based compensation are more likely to commit accounting irregularities. 3.3. Historical performance Firms with superior or satisfactory performance have no motive to falsify their accounting statements, whereas poorly performing rms and their executives have a clear motive to fudge the reports (especially when their incentive-based compensation depends on performance). The historical performance hypothesis may then be stated as follows: H3: Firms performing poorly are expected to be more likely to commit irregularities. 3.4. Debt covenant and political cost hypotheses Defond and Jiambalvo (1994) nd evidence of earnings management when rms are close to their lending covenant limits. They argue that rms violating debt covenants can be subjected to a costly re-contracting and management might have incentives to manage earnings to avoid such violations. The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

747

H4: Firms having relatively higher levels of leverage are more likely to commit accounting irregularities. Jones (1991) suggests a political cost hypothesis regarding the proclivity of rms to be engaged in earnings management. He proposes that due to their higher prole, larger rms should have more frequent disclosures, better reporting practices and be followed by a larger number of analysts. They should thereby be subject to greater public scrutiny (versus smaller rms). H5: Larger rms are less likely to commit accounting irregularities. 4. Data description and method of analysis 4.1. Data description The initial sample of AI announcements is obtained using the Dow Jones Interactive Library and a keyword search of accounting irregularities for the period between 1 January 1980 and 31 December 2004. The initial sample of 313 rms is subjected to the following restrictions. First, the announcements are made by publicly traded rms with nancial data available on the COMPUSTAT database. Therefore, announcements by private, not-for-prot and governmental entities were excluded. Second, the company has prices and returns available on Centre for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) over the period from 250 to 90 days before the announcement. Third, the announcement is specically related to AIs and it does not represent an accounting error. Fourth, the announcements do not represent AIs committed by subsidiaries or foreign entities. Finally, the company has compensation data available on ExecComp or the SECs EDGAR database. These requirements produce a sample of 152 announcement rms with complete nancial data available on the COMPUSTAT database. To compare the characteristics of AI rms to non-irregularity rms, this sample was matched with another 152 non-AI rms on the basis of size (total assets) and industry group (the rst two digits of the Standard Industrial Classication code). The total sample of 304 rms (152 AI rms and 152 matching rms) are used in the relevant univariate analysis and in model (3) of the logistic regression. Eightyve of the 152 AI rms have complete nancial and compensation data and are matched with 85 non-AI rms with complete nancial and compensation data.6 The total sample of 170 rms (85 AI rms and 85 non-AI matching rms) are

6

The principal reason for this drop in sample size is due to missing compensation data and it is related to the fact that the sample was collected from the period 1980 2004 (inclusive). This period is selected to try and maximize the sample size given the relative rarity of these irregularity announcements. The trade-off is that the compensation data is missing for many rms with announcements prior to 1995. The ExecComp database coverage starts in 1995 and the SEC proxy statement holdings date back to only 1995.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

748

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

used in the two reduced-form logistic regressions (models 1 and 2 in Table 3) and the univariate analysis. Financial variables are obtained from COMPUSTAT. These nancial variables are generally from the year prior to the announcement year. An obvious problem with collecting nancial data for rms involved in AIs is the issue of how reliable the balance sheet and income statement data will be if taken from a period involving the irregularity. To overcome (or minimize as much as possible) potential inaccuracies due to misstatements, the data used are taken from the restated nancial statements. If restated nancial reports are not available, the number of periods in which the company was involved in the irregularity is ascertained from the announcement. Then, nancial statements from the year prior to this time are used. The compensation data of the rms are collected from the ExecComp, otherwise it is manually collected from EDGAR database, the 10-K and DEF-14 A proxy statements. Compensation data are classied into the seven categories in this reports summary compensation tables. These tables show information related to the top ve ofcers (only) in the rm according to their rank. The categories include salary, bonus, other annual compensation (including perquisites and tax payment reimbursements), restricted stock awards, options or stock appreciation rights (SARs), long-term incentive plan payouts and all other compensation. The average dollar value of each category (except for options and SARs) for these top ve executives is calculated using data from the year prior to the announcement year. For options and SARs, the ve variables necessary to estimate the value of call options using the Black and Scholes (1973) model are obtained as described below. The exercise price and expiration date are collected from the proxy statement. Five year US Treasury bill rates are used as an estimate of the risk-free rate. The standard deviation of the underlying asset is estimated over the period from 250 days to 90 days relative to the announcement day using the market model. The underlying assets share price market value is the 10 day average price (from day 12 to day 2 relative to the announcement day). The value of the unexercised in-the-money options held by the top ve executives is also collected. The stock ownership percentage of all current directors and executive ofcers is also retrieved from the proxy statements for the year before the announcement year. 4.2. Logistic regression analysis In an effort to provide evidence on why rms become involved in AIs in the rst place, a matching sample of control rms not involved in AIs is constructed. A logistic regression model is developed to identify how the sample rms compare in regard to factors representing information asymmetry, the level and structure of management compensation, historical performance, debt usage and political costs. The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

749

Information asymmetry is difcult to model; hence, two variables drawn from the literature are used. The variables used to reect information asymmetry include the volatility of the AI rms stock price over the period of 250 to 90 days prior to the irregularity announcement (VOLAT ) and the number of analysts following the company (ANALYST ). The expectations for each variable using the logistic models are discussed below. Share price volatility is a common metric used to proxy information asymmetry. For example, Moeller et al. (2007) propose and use the variance of returns as a proxy for information asymmetry. They nd a positive and signicant relation between information asymmetry and volatility. A higher degree of information asymmetry provides the environmental conditions for companies to be less transparent. Hence, these rms are more likely to be involved in AIs and a positive relation is expected between return volatility and the likelihood of committing AIs. The existing empirical evidence strongly suggests that analyst coverage is negatively correlated with information asymmetry. Financial analysts play a signicant role in mitigating information asymmetry as they offer two services to market participants. First, they aggregate complex information and synthesize it in a form that is more easily understandable by less sophisticated investors. Second, they provide information that is not widely known by market participants. Hong et al. (2000) nd that companies with high analyst coverage are more informative and the protability of momentum strategies is lower for such rms. Barth and Hutton (2000) nd that stocks with high analyst coverage incorporate information on accruals and cash ows more rapidly than do prices of rms with lower coverage. Because fewer analysts indicate greater potential information asymmetry, there should be an inverse relationship between analyst coverage and the likelihood of committing an AI. Three proxies for management compensation are used. The ratio of total compensation to total assets (TCTA) is used to represent the level of compensation. The structure of compensation is represented by the percentage of equity-based compensation to total compensation (PEQC), as in Mehran (1995). Finally, the value of options exercised (VOETA) by the executives over the 1 year period prior to the discovery of the AI is calculated using the BlackScholes option pricing model and is scaled by total assets. All three of these variables are constructed so that higher values reect greater compensation. Therefore, under the management compensation hypothesis, there is expected to be a positive relationship between these three variables and the likelihood of engaging in AIs. Historical performance is measured by return on equity and whether the companys actual earnings per share were better than the analysts forecast. Return on equity (ROE) is calculated as net income divided by the book value of equity and is used to measure a rms historical operating protability. Defond and Jiambalvo (1991) indicate that managements with smaller earnings growth rates have the incentive to overstate earnings. Poorly performing management are expected to have greater incentive to be involved in AIs; hence, the expected The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

750

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

sign for the ROE variable is negative in the logistic regression. The other performance variable is a dummy variable (DANF), which equals 1 if the companys actual earnings per share (EPS) exceeded analyst forecasts and is 0 otherwise. A value of 1 for this variable indicates better-than-expected performance and these rms are hypothesized to have less incentive to commit AIs. Therefore, the expected sign for this performance variable is also negative. To provide evidence for the debt-covenant hypothesis, nancial leverage (LEV) is proxied by the ratio of total liabilities to the sum of total liabilities plus the market value of equity. Defond and Jiambalvo (1994) nd evidence of earnings management when rms are close to their lending covenant limits. They argue that rms that violate debt covenants can be subjected to a costly re-contracting and management might have incentives to manage earnings to avoid such violations. Therefore, higher levels of leverage are hypothesized to be positively related to the commission of AIs and its sign in the logistic regression is expected to be positive. Jones (1991) suggests a political cost hypothesis regarding the proclivity of rms to be engaged in earnings management. He proposes that due to their higher prole, larger rms should have more frequent disclosures, better reporting practices and be followed by a larger number of analysts. They should thereby be subject to greater public scrutiny (versus smaller rms). Under this hypothesis, larger rms should be less likely to become involved in irregularities and thereby the sign of this variable should be negative in the logistic regression. The log of total assets (SIZE) is used as a proxy variable to represent political cost. The dependent variable in the logistic regression is an indicator variable (AIRF), which takes the value 1 for AI rms and is 0 for the control group. Therefore, any signicant parameter estimates from the equation below provide evidence of the factors or characteristics hypothesized to represent an increased likelihood of taking part in AIs. AIRF = 0 + 1 (VOLAT) + 2 (ANALYST) + 3 (TCTA) + 4 (PEQC) +5 (VOETA) + 6 (ROE)+ 7 (DANF) + 8 (LEV) + 9 (SIZE) + . 5. Empirical results 5.1. Univariate tests comparing irregularity and non-irregularity rms Table 1 provides summary statistics for the proxy variables used to test the hypotheses, some detail on the scope of the irregularities and some general rmcharacteristic variables. These data are provided for both the irregularity rms as well for the non-irregularity rms, as appropriate. The mean and median differences for each variable between the irregularity versus non-irregularity rms are shown in the table (calculated as Non-AI rm value minus AI rm value). The Authors (1)

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

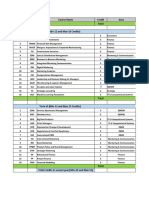

Table 1 Summary statistics of the proxy variables used to test the hypotheses Irregularity rms Variable Mean Median Non-irregularity rms Mean Median Mean Mean difference T-Stat Median difference Median Z-Stat

The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

A. Information asymmetry VOLAT 0.159 ANALYST 9.618 B. Historical performance ROE 0.056 CAR90 0.188 C. Debt covenant and political cost variables LEV 0.193 SIZE (Log) 6.515 D. Announcement characteristics AMOUNT ($US million) 472.548 AMTNI 3.635 TIME (QTR) 8.709 E. Summary statistics ASSETS ($US million) 9209.03 LTD ($US million) 1475.38 EPS ($US) 0.384 NI ($US million) 204.723 OPNCF ($US million) 405.36

0.067 7.300 0.071 0.147 0.146 6.186 21.000 0.211 7.000 485.85 79.11 0.570 7.155 21.370

0.053 12.685 0.157 NA 0.239 6.404 NA NA NA 6160.92 1100.17 0.589 246.990 480.870

0.033 8.500 0.105 NA 0.169 6.204 NA NA NA 494.86 107.40 0.900 12.470 26.52

0.106 3.067 0.214 NA 0.0471 0.111 NA NA NA 3048.00 375.20 0.205 42.276 75.517

4.790*** 2.880*** 1.050 NA 1.770*** 0.420 NA NA NA 0.990 0.950 0.830 0.400 0.380

0.034 1.200 0.034 NA 0.023 0.018 NA NA NA 9.010 28.290 0.330 5.245 5.150

5.055*** 2.447*** 1.274 NA 0.652 0.295 NA NA NA 0.295 0.163 2.093*** 1.397 1.036

*** denotes signicance at the 1 per cent level. Mean and median comparison of the proxies used in the univariate and logistic regression analysis of rms involved in accounting irregularities and a matching sample of rms not involved in accounting irregularities. The two proxies for the information asymmetry hypothesis are VOLAT, which is the standard deviation of returns estimated over the period of 250 to 90 days prior to the announcement, and ANALYST, which is the number of analysts following the rm. Two proxies for rm historical performance are ROE (net income divided by book-value of equity) and CAR90 (the cumulative abnormal return from the market model over the period from day t 90 up through day t 2 before the announcement day). Firm debt characteristics and political cost are controlled for by using LEV (long-term debt divided by total assets) and SIZE (measured as the log of total assets), respectively. Accounting irregularity announcement characteristics include AMTNI, which is the dollar amount (AMOUNT) of the accounting irregularity (as stated in the announcement) divided by net income. TIME is the length of time (in quarters) during which the company was involved in the accounting irregularity (as stated in the announcement). ASSETS is the book value of total assets. LTD is long-term debt. EPS is earnings per share excluding extraordinary items. NI is net income. OPNCF is the operating net cash ow. The Mean (Median) Difference for each variable is calculated as the mean (median) of non-accounting irregularity rms minus the mean (median) of accounting irregularity rms. T-Stat is the t-test statistic testing if the mean difference between the two samples is signicantly different from zero. Z-Stat is the non-parametric Wilcoxon z-statistic testing for a signicant difference between the two medians. NA is not applicable.

751

752

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

The univariate7 t-test statistic (T-Stat), testing whether the mean difference is signicantly different from zero, is shown as well as the non-parametric Z-statistic (Z-Stat), testing for a signicant difference in medians. Table 1 shows that the mean (median) VOLAT proxy measure is 15.9 per cent (6.7 per cent) for irregularity rms compared to 5.3 per cent (3.3 per cent) for the non-irregularity rms. Both the mean (T-Stat = 4.79) and median (ZStat = 5.055) test statistics are signicant at the 1 per cent level. Given the way the test statistics are calculated, these results are consistent with signicantly greater stock-price volatility for AI rms in the period preceding the irregularity than their non-AI counterparts. The mean number of analysts following a rm (ANALYST) is higher for nonAI rms (12.69) compared to AI rms (9.62), as expected. The t-test statistic of 2.88 indicates that this difference in ANALYST means is signicantly different at the 1 per cent level. The results for the median comparison are essentially the same. These ndings are interpreted as indicating that, on average, fewer analysts follow AI rms and they thereby are subject to greater information asymmetry. Therefore, given a motive, these rms have greater opportunity to be involved in these irregularities. The rst performance variable is return on equity. Table 1 shows that the mean ROE for AI rms equals 5.6 per cent (median = 7.1 per cent) while that for the non-AI rms is 15.7 per cent (median = 10.5 per cent). Although neither test statistic is statistically signicant, AI rms are shown to be exhibiting poorer performance. The second performance variable (CAR90) is the pre-announcement return and for the AI rms it equals 18.8 per cent (median = 14.7 per cent). This large negative return suggests that the market was aware of problems with these rms. It seems entirely possible that because this sample of rms committed the irregularities, and the irregularities typically involve earnings management, a motive of those involved was to mitigate this poor past performance. The mean of the LEV control variable in the univariate analysis shows that long-term debt represents an average of 19.3 per cent of total assets, which is signicantly lower (t-statistic = 1.77) at the 1 per cent level than the same ratio (23.9 per cent) for non-irregularity rms. However, there is no signicant difference based on the z-statistic test for a difference in medians. This suggests that the signicant difference in means might be inuenced by skewness of the values of the LEV variable. Table 1 also reports three characteristics in regard to the magnitude and duration of the AIs. The mean irregularity restatement amount equals $US472.5m

7

Correlation analysis has been conducted between the independent variables used in the analysis. In the interest of brevity, these results are described here rather than shown in a table. The signicant correlations (at a minimally 10 per cent level) are as follows (sign in parentheses): ANALYST with TCTA (), PEQC (+) and SIZE (+), TCTA with VOETA (+), LEV () and SIZE (), PEQC with DANF () and SIZE (+), and nally, VOETA with LEV () and SIZE ().

The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

753

whereas the median is only $US21m. This meanmedian difference suggests that a number of the restatements are comparatively large. Again, the mean restatement amount at 3.64 times net income (AMTNI) is much higher than the median (0.21 times) and afrms the previous conclusion. On average, companies are involved in irregularities for a period of 8.7 quarters (about 2 years and 2 months). An examination of the general rm characteristics is shown in the bottom section of the table. The z-statistic (2.093) for the earnings per share variable shows that the median for AI rms of $US0.57 is signicantly lower (at the 1 per cent level) than that of its non-irregularity counterpart of $US0.90. This nding supports the view that the rms who commit AIs are not performing as well as the matching non-AI rms. Table 2 shows descriptive and univariate t-test and z-test statistics for the management compensation data. In the line below each of these statistics, the compensation number is stated as a percentage of total compensation. The mean salary (as a percentage of total compensation) for the top ve executives of irregularity rms (25.9 per cent) is signicantly lower than that for non-AI rms (37.2 per cent) at the 1 per cent level (T-Stat = 3.00). Similarly, the AI rms scaled median salary (19.5 per cent) is signicantly lower at the 1 per cent level than their non-AI counterparts (31.7 per cent). Total current compensation (TCC) is the sum of salary, bonus, and other annual compensation. Mean (median) TCC as a percentage of total compensation equals 41.9 per cent (37.3 per cent) for irregularity rms, which is signicantly lower (at the 1 per cent level) compared to the non-irregularity rm mean (median) of 54.6 per cent (46.8 per cent). Therefore, the salary/guaranteed portions are signicantly lower for irregularity rms based on both measures. These gures suggest that maximization of equity-based compensation is a potential motive for executives of AI rms being involved in these irregularities. Conversely, executives of irregularity rms receive both signicantly higher average ($US3.576m) and median ($US779 000) incentive compensation (BSVAL) in the form of stock options (based on BlackScholes values) compared to their non-irregularity counterparts whose average (median) stock options are worth $US1.431m ($US253 000). Both the T-Stat (1.81) and the non-parametric Z-Stat (2.36) are signicant at the 1 per cent level. The same comparative results are also found when the BSVAL variable is scaled by total compensation. Total equity-based compensation (TEQC) is the sum of restricted stock awards, the BlackScholes value of options, long-term investment plans, and all other (non-current) compensation. For irregularity rms, total equity-based compensation averages $US4.128m and represents 58.1 per cent of total compensation. In contrast, non-irregularity rm executives average $US1.949m, which is 45.4 per cent of their total compensation. The mean differences are signicant at the 1 per cent level on both an absolute and relative basis. The results for the absolute and relative medians also indicate signicantly higher The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

The Authors

754

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

Table 2 Management compensation summary statistics Irregularity rms Variable Salary Bonus OAC TCC RSAW BSVAL LTIP AOC TEQC TC TCTA (%) VOETA (%) Mean 392.04 0.259 463.72 0.160 23.550 0.014 855.76 0.419 314.36 0.065 3576.08 0.458 113.640 0.020 132.89 0.037 4127.96 0.581 4983.72 0.180 0.090 Median 339.11 0.195 226.33 0.142 0.90 0.000 559.27 0.373 0.000 0.000 779.31 0.484 0.000 0.000 21.19 0.016 966.86 0.627 1777.81 0.090 0.010 Non-irregularity rms Mean 373.22 0.372 439.11 0.173 21.43 0.015 812.33 0.546 176.29 0.054 1431.15 0.336 62.49 0.012 278.68 0.053 1948.61 0.454 2760.95 0.140 0.060 Median 331.83 0.317 188.30 0.143 0.000 0.000 545.55 0.468 0.000 0.000 253.02 0.354 0.000 0.000 14.690 0.021 592.44 0.532 1079.25 0.080 0.010 Mean 18.810 0.112 24.610 0.014 2.120 0.001 43.420 0.126 138.10 0.011 2136.00 0.122 51.140 0.009 145.80 0.016 2179.35 0.126 2223.00 0.039 0.030 Mean difference T-Stat 0.62 3.00*** 0.170 0.650 0.21 0.150 0.28 2.850*** 1.29 0.62 1.810*** 2.660*** 1.06 0.99 1.08 1.19 1.940*** 2.850*** 1.670** 1.020 2.170*** Median difference Median 7.285 0.122 38.030 0.001 0.900 0.000 13.720 0.095 0.000 0.000 526.63 0.130 0.000 0.000 6.500 0.005 374.42 0.095 698.56 0.010 0.000 Z-Stat

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

0.713 2.379*** 0.913 0.506 0.441 0.476 0.691 2.575*** 0.476 0.328 2.357*** 2.684*** 1.325 1.331 0.951 0.813 2.146*** 2.575*** 1.849*** 1.021 0.124

*** and ** denote signicance at the 1 and 5 per cent levels, respectively. The compensation data are drawn from the ExecComp database, EDGAR database, and the SEC 10-K and DEF-14A reports. The information in these reports is for the top ve company executives. Salary is the annual salary. Bonus is the annual bonus. OAC is other annual compensation, which includes housing, relocation allowance, tax payments, etc. TCC is the total current compensation found as the sum of salary, bonus and other annual compensation. BSVAL is the value of stock options granted evaluated using the BlackScholes model. RSAW is the value of restricted stock awards. LTIP is the value of long-term investment plans. AOC is all other compensation. TEQC is the total equity-based compensation, which is the sum of restricted stock awards, option value, long-term investment plans and all other compensation. Total compensation (TC) is the sum of total current compensation and total equity-based compensation. TCTA is the total compensation divided by total assets. VOETA is the value of options exercised prior to the accounting irregularity announcement divided by total assets. The Mean (Median) Difference for each variable is calculated as the mean (median) of nonaccounting irregularity rms minus the mean (median) of accounting irregularity rms. T-Stat is the t-test statistic testing if the mean difference between the two samples is signicantly different from zero. Z-Stat is the non-parametric Wilcoxon z-statistic testing for a signicant difference between the two medians. Numbers are shown in thousands of dollars unless noted otherwise. The number in the line below each variable represents the percentage relative to total compensation.

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

755

values of TEQC for irregularity rms. This evidence points to a motive for why rms commit AIs. Actions that overstate income, understate expenses or decrease tax liability, for example, would improve the bottom line and make this incentivebased compensation more valuable. Table 2 also shows that irregularity-rm executives receive higher, average total compensation (TC = $US4.983m) than their non-irregularity counterparts who average $US2.761m. The difference is signicant at the 5 per cent level. The same comparison based on medians shows that TC for AI rms is signicantly higher at the 1 per cent level. These ndings support the conclusion of Klinger et al. (2002) that CEOs involved in AIs earn more than those at typical, non-irregularity rms. However, when total compensation is scaled by total assets (TCTA), the difference in ratios is not signicant. An issue of interest to the average stockholder of the irregularity rms should be whether the top ve executives exercised any of their options in the year prior to the AI announcement. For the irregularity rms, the mean percentage of options exercised (VOETA) represents 0.09 per cent of total assets. This VOETA gure for options exercised over the comparable period by non-irregularity rms is 0.06 per cent and this is signicantly lower at the 1 per cent level. This nding for irregularity rms suggests that the executives are acting in their own self-interest and that there is an element of calculation in terms of the timing of the options being exercised.8 However, this result might potentially be inuenced by outliers as the medians are not signicantly different. 5.2. Results of the logistic regression The results of the logistic regression are presented in Table 3. The objective of this analysis is to compare the characteristics of irregularity (versus the matching non-irregularity) rms in an attempt to identify why the former rms actually became involved in these actions. The results for three different regression models are reported. Both models (1) and (2) include compensation variables and are thereby based on 170 observations, whereas model (3) does not include these data; hence, the sample size is expanded to 304 observations. The VOLAT and ANALYST information asymmetry variables both have the expected signs and are signicant in all three logistic regression models examined. The volatility result shows that the stock of AI rms exhibit relatively greater uncertainty in the period prior to the irregularity announcement. Furthermore, rms being followed by fewer analysts are more likely to commit AIs. This evidence supports the hypothesis that high information asymmetry rms attempt

8

Management typically does not know exactly when the truth will come out. In most cases, the irregularities are discovered and reported by other parties like auditors, whistle blowers, previous employees, the SEC, etc. Those managers involved are unlikely to make the rst confession because they presumably would not have committed these illegal acts (or allowed them to happen) if they expected the illegalities to be discovered.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

756

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

Table 3 Logistic regression analysis AIRF = 0 + 1 (VOLAT ) + 2 (ANALYST) + 3 (TCTA) + 4 (PEQC) + 5 (VOETA) + 6 (ROE) + 7 (DANF) + 8 (LEV) + 9 (SIZE) + . Model 1 Variable Sign Estimate 4.196 20.599 0.236 2.905 123.100 2.944 0.100 3.251 0.827 T-Stat 3.005*** 2.405** 4.453*** 2.603** 0.811 1.857* 0.189 1.655* 3.320*** 170 0.375 Model 2 Estimate 3.601 19.002 0.194 35.199 126.3 3.007 0.098 2.888 0.865 T-Stat 2.265** 2.388** 4.186*** 0.325 0.909 1.907* 0.198 1.582 3.502*** 170 0.415 Model 3 Estimate 2.264 7.641 0.140 0.567 0.435 0.457 0.559 T-Stat 3.235*** 1.987** 4.182*** 1.584 1.347 0.476 3.911*** 304 0.589

Intercept NA VOLAT + ANALYST TCTA + PEQC + VOETA + ROE DANF LEV + SIZE Number of observations Pseudo R2

***, ** and * denote signicance at the 0.1, 1 and 5 per cent levels, respectively. In this logistic regression model, the dependent variable is an indicator variable (AIRF) that is equal to 1 if the observation is from a rm involved in an accounting irregularity and is 0 if it is from an uninvolved matching rm. Matching rms are selected on the basis of their four-digit Standard Industrial Classication code and total assets. The information asymmetry proxies are VOLAT (the return standard deviation over the period of days 250 to 90 prior to the announcement) and ANALYST (the number of analysts following the rm). Proxies for the level and the structure of management compensation are TCTA (total compensation divided by total assets), and PEQC (the ratio of total equity-based compensation to total compensation), respectively. VOETA is the BlackScholes option pricing model value of options exercised by executives during the 1 year period prior to the accounting irregularity, divided by total assets. The proxies for historical performance are ROE (net income divided by the book value of equity) and DANF (a dummy variable equal to 1 if the companys earnings per share exceed analysts forecasts, and 0 otherwise). LEV equals long-term debt divided by total assets. SIZE is proxied by the log of total assets. Sign is the parameter estimates expected sign. T-Stat is the t-test statistic testing if the parameter estimate is signicantly different from zero.

to take advantage of having less transparent operations and risk the falsication of their accounting reports. The percentage of equity compensation variable (PEQC) is found to have the hypothesized negative sign and is also signicant at the 1 per cent level in model (1) (this variable is not included in model 2 because it is highly correlated with TCTA). This result is consistent with Hypothesis 2, which predicts that rms with executives who have relatively higher equity-based compensation are more likely to be involved in irregularities. This evidence reinforces the conclusion drawn from the univariate tests that the manipulation of earnings might be motivated by the desire of executives to enhance the value of their stock options. The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

757

The ROE performance variable proves to be signicant at the 5 per cent level in both models (1) and (2). The coefcients signs are negative as theorized in Hypothesis 3, and this result is consistent with poor performance being a motive for the commission of irregularities. Both the leverage and size control variables prove to be signicant. The LEV variables coefcient is positive and is signicant at the 5 per cent level in model (1). The fact that this coefcients sign is positive supports the debt covenant hypothesis and suggests that highly levered rms are more likely to commit the AIs. The SIZE variable is both negative and signicant at the 0.1 per cent level in all three models. This result (as well as the previous nding for the ANALYST variable) provides evidence on the proposed political-cost hypothesis and suggests that, indeed, larger and more visible rms are less likely to be involved with these irregular accounting activities. The logistic regressions exhibit very reasonable levels of goodness-of-t based on the pseudo R2s, which might be interpreted like the coefcient of determination in a typical multiple regression. 6. Summary and conclusions The present paper develops empirical evidence to investigate the claim that incentive-based compensation structure can be linked to the commission of AIs. First, evidence regarding the materiality of the irregularities shows that they are signicant events. The average amount of the income restatements due to the irregularities is $US472.5m and this mean represents 363.5 per cent of these rms average net income. Furthermore, the types of irregularities committed are described predominantly in the announcements as being overstatements of revenue, income or prot, early recognition of income, phantom sales and overstating assets. Therefore, they are typically revenue-enhancing actions. Both facts are consistent with the irregularities having been committed to disguise signicant losses. Second, irregularity rms are found to exhibit signicantly poorer earnings performance in the time period leading up to the irregularity announcements. Third, the top executives at the AI rms are found to receive a signicantly larger percentage of their pay package in the form of equity-based compensation. Therefore, the rms committing the irregularities are shown to have a motive, as they exhibit poorer operating performance and have greater equity-based compensation. Irregularity rms are also shown to exhibit greater stock price volatility in the period preceding the AI announcements. Furthermore, they are followed by signicantly fewer stock analysts and are relatively smaller in size than their non-irregularity counterparts. Taken together, these attributes suggest opportunity in that the irregularity rms have greater information asymmetry and are less visible. This lack of transparency is consistent with creating an environment in which those managers responsible for committing the irregularities feeling that they were not likely to get caught. In conclusion, these less transparent and The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

758

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

lower prole AI rms have greater opportunity and greater motivation due to poor performance and more equity-based compensation. In the present research they are shown to be more likely to commit the AIs. The results of the present study show that public, government and shareholder concerns with regard to the impact of AIs on shareholders wealth are warranted. The extent of these illegal activities is shown to have a large impact not only on the rms because of the resulting restatements of income, but also on shareholders through a signicant loss of their stocks market value arising directly from the announcement of the irregularity. The recent attempts by the US federal government to better control incidents of corporate dishonesty as manifested in improper and illegal accounting practices through passage of the SarbanesOxley Corporate Reform Act of 2002, seem to be well founded based on the ndings of this research as well as those in other studies, such as Richardson (2000). Among the Acts aims are to expose and punish dishonest corporate leaders while recognizing those who are honest by lifting the shadow of suspicion from them.9 The Act specically notes that the high standards of the accounting profession will be enforced and that both auditors and accountants will be held accountable. Both shareholders and rm employees are expected to benet. The former because the nancial report does not contain any untrue statement of a material fact or omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made . . . not misleading.10 The latter because reckless corporate practices that articially inate stock prices and lead to corporate failure will not be tolerated. References

Abowd, J. M., and D. S. Kaplan, 1999, Executive compensation: six questions that need answering, Journal of Economic Perspectives 13, 145 168. Bar-Gill, O., and L. Bebchuk, 2003, Misreporting corporate performance, working paper (Harvard Law School, Cambridge, MA). Barth, M. E., and A. P. Hutton, 2000, Information intermediaries and the pricing of accruals, working paper (Stanford University, Stanford, CA). Black, F., and M. Scholes, 1973, The pricing of options and corporate liabilities, Journal of Political Economy 81, 637 654. Ofce of the Press Secretary, 2002, President Bush signs corporate corruption bill, White House Press Release, July 30 (The White House, Washington, DC). Defond, M. L., and J. Jiambalvo, 1991, Incidence and circumstances of accounting errors, Accounting Review 66, 643 655. Defond, M. L., and J. Jiambalvo, 1994, Debt covenant violation and manipulation of accruals, Journal of Accounting and Economics 17, 145 176. Denis, D., P. Hanouna, and A. Sarin, 2005, Is there a dark side to incentive compensation? working paper (Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, and Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA).

9 10

Paraphrased from White House Press Release, 30 July 2002. House Resolution 3763 (SarbanesOxley Act of 2002), p. 33, Sec. 302a, (2).

The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

759

Duru, A. I., and R. J. Iyengar, 2001, The relevance of rms accounting and market performance for CEO compensation, Journal of Applied Business Research 17, 10718. Dye, R. A., 1988, Earnings management in an overlapping generations model, Journal of Accounting Research 26, 195 235. Elitzur, R. R., and V. Yaari, 1995, Executive incentive compensation and earnings manipulation in a multi-period setting, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 26, 201219. Erickson, M., M. Hanlon, and E. L. Maydew, 2006a, Is there a link between executive equity incentives and accounting fraud, Journal of Accounting Research 44, 113 143. Erickson, M., M. Hanlon, and E. L. Maydew, 2006b, How much will rms pay for earnings that do not exist? Evidence of taxes paid on allegedly fraudulent earnings, working paper (University of Chicago, Chicago, IL). Gaver, J. J., K. M. Gaver, and J. R. Austin, 1995, Additional evidence on bonus plans and income management, Journal of Accounting and Economics 19, 3 28. Goldman, E., and S. Slezak, 2006, An equilibrium model of incentive contracts in the presence of information manipulation, Journal of Financial Economics, 80, 603626. Hall, B. J., and K. Murphy, 2002, Stock options for undiversied executives, Journal of Accounting and Economics 33, 342. Hanlon, M., S. Rajgopal, and T. Shevlin, 2003, Are executives stock options associated with future earnings? Journal of Accounting and Economics 36, 3 43. Healy, P. M., 1985, The effect of bonus schemes on accounting decisions, Journal of Accounting and Economics 7, 85 107. Healy, P. M., and J. M. Wahlen, 1999, A review of the earnings management literature and its implications for standard setting, Accounting Horizons 13, 365383. Hemmelberg, G., G. Hubbard, and D. Palia, 1999, Understanding the determinants of managerial ownership and the link between ownership and performance, Journal of Financial Economics 53, 353384. Holthausen, R. W., D. F. Larcker, and R. G. Sloan, 1995, Annual bonus schemes and the manipulation of earnings, Journal of Accounting and Economics 19, 29 74. Hong, H., T. Lim, and J. C. Stein, 2000, Bad news travels slowly: size, analyst coverage, and the protability of momentum strategies, Journal of Finance 55, 256 295. SarbanesOxley Act, 2002, House Resolution 3763, 107th Congress of the United States, Washington, DC [online; last accessed: 15 March, 2007. http://1.ndlaw.com/news. ndlaw.com/hdocs/docs/gwbush/sarbaneoxley072302.pdf]. Available: www.ndlaw.com. Jensen, M. C., 2003, Paying people to lie: the trust about the budgeting process, European Financial Management 9, 379 406. Jensen, M. C., and W. Meckling, 1976, Theory of the rm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure, Journal of Financial Economics 3, 305360. Jensen, M. C., and K. J. Murphy, 1990, CEO incentives its not how much you pay, but how, Harvard Business Review 68, 138 153. Jones, J., 1991, Earnings management during import relief investigations, Journal of Accounting Research 29, 193 228. Klinger, S., C. Hartman, S. Anderson, J. Cavanagh, and H. Sklar, 2002, Executive Excess 2002: CEOs Cook the books, skewer the rest of us, Ninth Annual CEO Compensation Survey [online; last accessed: 24 March, 2006. http://www.faireconomy.org/les/Executive_ Excess_2002.pdf]. Available: www.ufenet.org. Levitt, A., 2000, Commissions auditor independence proposal, Testimony before the Senate Subcommittee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, 28 September 2000. Main, B. G. M., A. Bruce, and T. Buck, 1996, Total board remuneration and company performance, Economic Journal 106, 16271644. McKnight, P. J., and C. Tomkins, 1999, Top executive pay in the United Kingdom: a corporate governance dilemma, International Journal of the Economics of Business 6, 223243.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

760

F. A. Elayan et al./Accounting and Finance 48 (2008) 741760

Mehran, H., 1995, Executive compensation structure, ownership, and rm performance, Journal of Financial Economics 38, 163 184. Meulbroek, L., 2001, The efciency of equity linked compensation: understanding the full cost of awarding executive stock options, Financial Management 30, 5 30. Moeller, S. B., F. P. Schlingemann, and R. M. Stulz, 2007, How do diversity of opinion and information asymmetry affect acquirer returns? Review of Financial Studies 20, 20472078. Rajgopal, S., and T. Shevlin, 2002, Empirical evidence on the relation between stock option compensation and risk taking, Journal of Accounting and Economics 33, 145171. Richardson, V. J., 2000, Information asymmetry and earnings management: some evidence, Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 15, 325 347. Trueman, B., and S. Titman, 1988, An explanation for accounting income smoothing, Journal of Accounting Research 26, 127139.

The Authors

Journal compilation 2008 AFAANZ

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- BSBA Financial Management CurriculumДокумент3 страницыBSBA Financial Management Curriculumrandyblanza2014Оценок пока нет

- PIP Storage Tanks PDFДокумент83 страницыPIP Storage Tanks PDFManuel HernandezОценок пока нет

- Adugna LemiДокумент25 страницAdugna LemiDr.Hira EmanОценок пока нет

- Work Experience:: Retail Logistics LLC Steinweg Sharaf Fze Sharaf Shipping Agency LLCДокумент3 страницыWork Experience:: Retail Logistics LLC Steinweg Sharaf Fze Sharaf Shipping Agency LLCDr.Hira EmanОценок пока нет

- Toyota Vehicles For FemaleДокумент4 страницыToyota Vehicles For FemaleDr.Hira EmanОценок пока нет

- TB 1Документ20 страницTB 1Dr.Hira EmanОценок пока нет

- Economic Research1Документ11 страницEconomic Research1Dr.Hira EmanОценок пока нет

- Internal Strengths Internal Weaknesses: StrategiesДокумент1 страницаInternal Strengths Internal Weaknesses: StrategiesDr.Hira Eman100% (1)

- Unit 4 - MarketingДокумент27 страницUnit 4 - MarketingSorianoОценок пока нет

- Brief Note On The Trusteeship Approach As Proposed by Mahatma Gandhi - Business Studies - Knowledge HubДокумент2 страницыBrief Note On The Trusteeship Approach As Proposed by Mahatma Gandhi - Business Studies - Knowledge HubSagar GavitОценок пока нет

- Word DiorДокумент3 страницыWord Diorlethiphuong15031999100% (1)

- Electives Term 5&6Документ28 страницElectives Term 5&6GaneshRathodОценок пока нет

- Sales Inquiry FormДокумент2 страницыSales Inquiry FormCrisant DemaalaОценок пока нет

- 4PS and 4esДокумент32 страницы4PS and 4esLalajom HarveyОценок пока нет

- Tax Invoice/Bill of Supply/Cash Memo: (Original For Recipient)Документ1 страницаTax Invoice/Bill of Supply/Cash Memo: (Original For Recipient)Syed SameerОценок пока нет

- Taylor Nelson Sofres: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaДокумент4 страницыTaylor Nelson Sofres: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaMonique DeleonОценок пока нет

- UTI - Systematic Investment Plan (SIP) New Editable Application FormДокумент4 страницыUTI - Systematic Investment Plan (SIP) New Editable Application FormAnilmohan SreedharanОценок пока нет

- Presidential Decree No 442Документ10 страницPresidential Decree No 442Eduardo CatalanОценок пока нет

- Warehouse Layout OptimizationДокумент4 страницыWarehouse Layout OptimizationJose Antonio UrdialesОценок пока нет

- Report PT Bukit Uluwatu Villa 30 September 2019Документ146 страницReport PT Bukit Uluwatu Villa 30 September 2019Hanif RaihanОценок пока нет

- TPM PresentationДокумент40 страницTPM PresentationRahul RajpalОценок пока нет

- XYZ Investing INC. Trial BalanceДокумент3 страницыXYZ Investing INC. Trial BalanceLeika Gay Soriano OlarteОценок пока нет

- Offer in Compromise Requirement LetterДокумент2 страницыOffer in Compromise Requirement LetterSagar PatelОценок пока нет

- Sample Questions For Itb Modular ExamДокумент4 страницыSample Questions For Itb Modular Exam_23100% (2)

- Chapter 12: Big Data, Datawarehouse, and Business Intelligence SystemsДокумент16 страницChapter 12: Big Data, Datawarehouse, and Business Intelligence SystemsnjndjansdОценок пока нет

- Aviva Life InsuranceДокумент20 страницAviva Life InsuranceGaurav Sethi100% (1)

- BfinДокумент3 страницыBfinjonisugandaОценок пока нет

- Portfolio Management Meaning and Important Concepts: What Is A Portfolio ?Документ17 страницPortfolio Management Meaning and Important Concepts: What Is A Portfolio ?Calvince OumaОценок пока нет

- Functional DocumentДокумент14 страницFunctional DocumentvivekshailyОценок пока нет

- Management 111204015409 Phpapp01Документ12 страницManagement 111204015409 Phpapp01syidaluvanimeОценок пока нет

- HR Pepsi CoДокумент3 страницыHR Pepsi CookingОценок пока нет

- 20092018090907893chapter18 RedemptionofPreferenceSharesДокумент2 страницы20092018090907893chapter18 RedemptionofPreferenceSharesAbdifatah SaidОценок пока нет

- IBC Chap 2Документ28 страницIBC Chap 2Chilapalli SaikiranОценок пока нет

- Renewal Notice 231026 185701Документ3 страницыRenewal Notice 231026 185701Mahanth GowdaОценок пока нет

- Is Enhanced Audit Quality Associated With Greater Real Earnings Management?Документ22 страницыIs Enhanced Audit Quality Associated With Greater Real Earnings Management?Darvin AnanthanОценок пока нет

- Price Action TradingДокумент1 страницаPrice Action TradingMustaquim YusopОценок пока нет