Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

GE Heathcare BOP Article

Загружено:

Mustafa HussainИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

GE Heathcare BOP Article

Загружено:

Mustafa HussainАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Getting It Right at the Bottom of the Pyramid

How GE Healthcare Married Community Needs with Corporate Imperatives and Birthed a Business Segment and a Movement By Nancy Musselwhite, Senior Consultant

The Company GE Healthcare is a $17 billion unit of General Electric, the $180 billion global manufacturer of aircraft engines, generators and turbines, locomotives and other transportation equipment, medical imaging equipment, lighting, home appliances, and electric distribution and control equipment. GEs genesis was the home laboratory of an inventor, Thomas Edison, who ultimately held 1,093 US patents and wanted to solve problems for people: problems related to illumination, power, sound, communication, and transportation. Edison wanted to change lives by making technological advances accessible to average people. The Country India is seventh largest country in the world but (at 1/3 the size of the US) contains four times the population - 1.17 billion people. The population density picture is complicated by the countrys vulnerability to natural hazards, misdistribution of resources, persistent poverty, lagging infrastructure development, and poor agricultural practices. Life expectancy lags, and gross national income per capita is $1,070. The country understands that education is key to changing the economics of the country and since independence (1947) has been working to improve access to and the quality of primary and secondary education available to its citizens. As a result of this focus, India today contains a surplus of the highlytrained researchers and engineers: a fact not lost on multinational corporations. Many players, watching labor clusters and calculating wage rates in the US/EU versus India, have made decisions to develop R&D centers in India, including GE. The John F. Welch Technology Centre in Bangalore was inaugurated on September 17, 2000. Spread over 50 acres, the $175 million, 1.15 million sft, John F. Welch Technology Centre houses state-of-the-art laboratories and facilities to conduct research and development for GE businesses worldwide. Today, the center supports 4,200 scientists, researchers and engineers who redefine what is possible in the healthcare, energy, transportation, aviation, financial and entertainment business. In healthcare, R&D initiatives at the center involve work on molecular imaging and diagnostics, capacitive micromachined ultrasound transducers (cMUTs), volume CT, next generation MRI (massively parallel MR, 7 Tesla Imaging Systems), advanced navigation technologies for interventional X-ray applications, X-ray tomo synthesis, time of flight positron emission tomography, and computational biology & biostatistics.

While much of the work done at the center develops high-end products that benefit the lives of those living in developed countries, a team of scientists and researchers changed GEs perspective on the Bottom of the Pyramid forever. Bottom of the Pyramid Concept In 2004, author C. K. Prahalad delivered a paradigm-shattering book entitled The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits. The book challenged the notion that the only way to improve the lives of those living in poverty at the Bottom of the Pyramid (hereafter BOP) was through public and non-profit sector intervention. The book suggested that the private sector has a critical role to play in the alleviation of global poverty- not by donating product but by selling product that benefits the lives of people making less than $2/day. The pyramid developed by Prahalad divides the world into four tiers:

The world pyramid

Purchasing power parity in USD >$20,000 Population in millions

Tier 1

75-100

$1,500-20,000

Tier 2-3

1,500-1,750

<$1,500

Tier 4

4,000

Source: Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid C.K. Prahalad Selling to the worlds poorest people (approximately 4 billion people) means a reexamination of the priceperformance relationships for products/services coupled with a new level of capital efficiency. Because of that, selling to the BOP presents a managerial challenge that requires a transformation of managerial practices in established multinational corporations. BOP strategies are about giving the massive population base living on less than $2/day access to solutions that radically improve their wellbeing. While geography and infrastructure are significant barriers, the greatest limiting factor is cost, according to authors Prahalad and Hart because poor have to pay a poverty penalty. This refers to the premium that they are required to pay for products for which the rich pay a lower price. The poor pay more for water, food, electricity, etc. because they buy lesser quantities.

A second limiting factor is dominant logic: players in both the public and private sector tend to operate in familiar ways and may be resistant to thinking outside the box.

Sectors are conditioned by dominant logic; abandoning familiarity/comfort zones is difficult.

Politicians, public policy establishments

Aid agencies

BOP latent 4 billion consumer opportunity Private sector, including multinational companies

NGOs, civil society organizations

Source: Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid C.K. Prahalad BOP initiatives may require private, public, and non-profit sector entities to develop partnerships or at least understand how to work in parallel within the new paradigm. Established managerial practices in multinational corporations require a paradigm shift in order to meet the needs of the bottom of the pyramid. Decision-makers within multinational corporations have not been conditioned to focus on solving problems for the worlds poorest. Successful BOP products deliver on three key questions: 1. Does it solve a problem for the poorest? 2. Is it economically viable? Does the business case hold up to scrutiny? 3. Is it scalable? Is it repeatable elsewhere? Paradigm Shift Soon after the opening of the Welch Technology Centre in 2001, a group of GE Healthcare researchers involved in the development of state-of-the-art healthcare diagnostic equipment had a moment of revelation. While working during the day on next-generation equipment destined for the worlds wealthiest, they took family members to local clinics bereft of diagnostic equipment, or clinics containing substandard equipment. What equipment existed at the local level in Indian towns and villages had not been manufactured to international quality standards.

The team suggested to GE management that they be allowed to explore the development of a prototype electrocardiogram device that was affordable and portable and could be used in-country in place of existing substandard equipment in local clinics and hospitals. Pushback from management jelled around two issues: the need for a solid business case (economic viability), and a need to fully understand how GE could sell to that end of the market. Historically within GE, approval to proceed with research for new product development turns on the ability to demonstrate a return on investment within three years of launch. Understanding that dynamic, the GE Healthcare team from Bangalore went back to management with a solid business case for developing an affordable and portable ECG for developing countries- a product that would show a return on investment to the company within an acceptable time frame. Evidence that there was a market at the bottom of the pyramid for this kind of diagnostic tool gave management what they were looking for. Approval to begin work was granted with an R&D outlay not to exceed $500,000.00 to develop the device, and a challenge to deliver a working product in 18 months. The biggest challenge for the team was not functionality: it was bringing the device to market within a price range that would be accepted by Indian healthcare workers and institutions. The research team recognized that a diagnostic device developed for this market would have to sell for $500-1000, and so developed a value segment. The new value segment focused on two things: a) keeping product costs down while keeping quality intact, and b) learning how/if the existing sales/marketing assets could be leveraged to sell to this segment. The second biggest challenge to GE was developing a new distribution model for the value segment. Even within India, GEs sales/marketing assets were dedicated to high-end equipment because that was the end of the market the company new best. Most of the $400-500 million in revenue that GE made in India was attributable to sales of high-end equipment, not product sold to the BOP. GE is the #1 provider in India of sophisticated ECG, MRI, CT and other diagnostic equipment. But the people that would benefit from GEs value segment work represented a completely different market for GE: different customers, different channels, different support requirements, etc. GEs Bangalore team had a few natural cost advantages. Computing power improved dramatically since GE brought the last ECG to market- putting faster processing speeds into ever tinier chips- so the new device would therefore have lower material costs (less plastic; smaller LCD screen). R&D costs would be lower since eight of the nine engineers involved with the project would be based in India, and GE made the decision to go with commercially-available chips which were one-quarter the price of customized processing chips. The team got feedback from doctors earlier in the process by using technology capable of delivering fast plastic mold prototypes, which prevented costly change orders later. They disassembled a semi-portable ECG built by GE in the '90s to learn how dust from India's rural roads jammed standard printers, and adapted a printer used in bus terminal kiosks in India capable of functioning in dusty environments. The research team redesigned the battery so it wouldn't be depleted sitting on a distributor's shelf, and simplified the software that interprets electrical impulses for doctors to prevent memory overload. Prototype accepted, GE began production 22 months after project approval, just a few months over the 18-month target for delivery. In India, GE partners with Wipro (WIT) for health-care manufacturing. Wipro Ltd. is a Bangalore-based technology company with $6 billion in sales and 100,000 employees. Wipro GE Healthcare, also headquartered in Bangalore, is a joint venture 51% owned by GE and handles manufacturing of GEs value-segment medical diagnostic devices. The Wipro-GE team recognized that in order to bring the ECG, named MAC 400, to market within their cost target, they would have to negotiate hard with procurement people: something local suppliers had not been accustomed to from GE. Local suppliers were ultimately used for all components parts.

In parallel to product development, GE had to develop the value-segment sales, marketing, and distribution model. The company had to create the means to put the MAC 400 into the hands of rural doctors and clinics. GE found a financing partner in the State Bank of India (SBI). SBI has over 16000 branches, giving it the largest branch network in India and reach into a number of rural locations where GE had never operated. With an asset base of $250 billion and $195 billion in deposits, SBIs size and reach made it the perfect banking partner. No-interest loans for rural doctors and clinics were part of the equation. The sales pitch to rural doctors and clinics was the second part: a business case for the device, showing how the MAC 400, at a cost of $1000, would pay for itself in less than 2 years at a utilization of x electrocardiograms per week, delivering an ECG report for less than $1/patient. In addition to meaningful business pitch, the company made strategic equipment donations to drive acceptance and penetration. GE accepted the fact that the profit margin of the MAC 400 per unit would be lower than the per unit profit margin of GEs higher-end equipment. While per-unit margins on the MAC 400 were within an acceptable range, the company understood that selling to the BOP would require a focus on volume: making sales numbers in India and then replicating successful healthcare market penetration in other developing countries. The MAC 400 has been an unprecedented success. Early feedback from the field indicated that doctors were bringing the device to rural locations that had never had access to ECG equipment and the equipment performed beautifully under a variety of environmental challenges. Since launch in India, the MAC 400 has been sold in over 100 countries and laid the groundwork for a whole family of products designed for the BOP market. Researchers needed only to point to the success of the MAC 400 (and its corresponding $20 million in revenue to GE) to validate the market at the bottom of the pyramid. In November 2009, GE Healthcare India released its latest ECG device: the MAC I. Smaller than a laptop and with a price tag of Rs 25,000 ($535), the MAC I slashes the cost of delivering an ECG bill to just Rs 9. ($.20 cents): six times lower than prevailing ECG rates and roughly equivalent to the cost of a bottle of mineral water. Again partnering with the State Bank of India, GE is putting this device in the hands of rural doctors with no-interest loans at a price that delivers a fast return on investment. Official early sales expectations on the MAC I are conservative at 5000 units, but informal estimates place sales expectations of the MAC I at no less than 35,000 units- worth another $19-20 million in revenue. Revenue from GE India could top $1 billion within four years, and we believe a growing percentage of revenue will be attributable to the value-segment product lines. One of the reasons MAC 400 was followed so quickly with the release of MAC I is that GE got its valuesegment legs. The company, with its manufacturing partner Wipro, quickly developed best-in-class value benchmarks for delivery of low-cost, high-quality diagnostic products. The investment by the doctor is made relatively painless by the delivery of a credit card by the State Bank of India, and is quickly recouped as the cost of the device is leveraged across hundreds of patients. Not just a product but a movement Last year GE Healthcare launched a six-year, $6-billion healthymagination campaign to deliver low-cost, quality products globally. The three tenets of healthymagination are to reduce costs, increase access, and improve quality. R&D will get $3 billion; GE also committed $2 billion toward financing, and $1 billion to related GE technology and content to drive healthcare IT in rural and underserved areas.

By 2015, GE expects to launch at least 100 innovations that lower cost, increase access and improve quality by 15% and work with partners on innovations across four critical initial need areas: accelerating healthcare information technology; targeting high-tech products to more affordable price points; broadening access to the underserved; supporting consumer-driven health. Healthymagination reflects the new opportunities we see in healthcare, according to GE Chairman and CEO Jeff Immelt. Our newest innovations low-cost digital x-ray machines, portable ultrasounds, more affordable cardiac equipment will save costs for doctors, hospitals, the government, families and businesses. This will help level the playing field in health care. With our technology, rural and urban areas and developing countries can have access to the best technology, affordably. Not just a product but a miracle What GE researchers in Bangalore didnt know when they began work on a value-segment ECG is that Indians are at greater risk of heart disease than Europeans, Americans, and Asians. A genetic mutation found in 1 in 25 people in India almost guarantees development of heart disease. Indians suffer heart attacks at an earlier age and often without prior symptoms or warning. According to Medwin Heart Foundation, half of all heart attacks among Indian men occur before the age of 50, and 25% occur before 40. India, a country of more than one billion people, could therefore account for up to 60% of heart disease patients worldwide next year. World Health Organization researchers had long been aware that heart disease was exceptionally prevalent in the sub-Indian continent, but it was only recently that scientists discovered the gene responsible. The research, published in January 2009 in the journal Nature Genetics, explained how a genetic mutation affecting 4% of Indians and 1% per cent of the world's population leads to formation of an abnormal protein that results in cardiomyopathy, a disease causing deterioration of the heart muscle. In southern India where cardiovascular disease claims a third of lives, a simple therapy like daily aspirin could have a significant impact on early-stage cardiovascular problems. "Because many deaths occur in a much younger age group compared to developed countries, cardiovascular disease has a significant economic and social consequence among families, especially in rural India, according to Rohina Joshi from The George Institute for International Health in Sydney, Australia. "The key finding from this new analysis is that while many treatments for the prevention of cardiovascular disease are low-cost and effective, the uptake of these drugs has been limited in this rural area of India." GE Healthcare researchers in Bangalore put the means of diagnosing heart problems into the hands of healthcare professionals in a country that needs it more than any other country in the world India. Conclusion GE Healthcare got it right at the bottom of the pyramid by making sure the product solved a problem for Indias poorest and that there was a viable and scalable business model. The value-segment paired high value to the community with high value to the corporation.

Moving to sustainable BoP strategies

High Not self-sustaining

Value to the community

Focus

Sustainable BoP strategy

Low Corporate philanthropy

Limited value to community

Value to the company

The genius of GE is that proven success in India has given the company a family of products that can be sold in dozens of countries across Asia, South America, and Africa to doctors and clinics serving populations living on $2/day. Local manufacturing and financing partners must be developed along with marketing and instruction in local languages, but initial development costs are then spread across an even broader basket of sales figures. If this was only about revenue, the story would be good. But the reality is that the story of GE Healthcare at the bottom of the pyramid is not only about positive return on investment: it is about saving lives. The company is gaining proponents one family at a time, and one doctor or clinic at a time. If the basic rules of corporate marketing include product, price, place, and promotion, GE Healthcare as an unbeatable combination: the right mix of life-saving products, a price the BOP can afford, delivered in rural villages beyond the reach of cardiac specialists, sparking a thousand stories that begin with the words they saved my fathers life

Nancy Musselwhite Senior Consultant 770-650-8495 Nancy@geostrategypartners.com www.geostrategypartners.com Market Intelligence | Competitive Positioning | Winning Strategies Where you are Where you need to be How you get there

Localize

Profitable venture

Вам также может понравиться

- The Innovation Process of A Company - An Aravind Eye Hospital Case Study.Документ3 страницыThe Innovation Process of A Company - An Aravind Eye Hospital Case Study.huss_hellraiser100% (1)

- GE HealthcareДокумент19 страницGE HealthcarePaskalis Sergius Noeng100% (2)

- Accelerating Commercialization Cost Saving Health Technologies ReportДокумент25 страницAccelerating Commercialization Cost Saving Health Technologies ReportBrazil offshore jobsОценок пока нет

- Building For The Environment 1Документ3 страницыBuilding For The Environment 1api-133774200Оценок пока нет

- HU - Century Station - PAL517PДокумент232 страницыHU - Century Station - PAL517PTony Monaghan100% (3)

- Stewart, Mary - The Little BroomstickДокумент159 страницStewart, Mary - The Little BroomstickYunon100% (1)

- Case 1 - GE Globalizes Its Medical System BusinessДокумент2 страницыCase 1 - GE Globalizes Its Medical System Businessdinar50% (2)

- Biocon Case Study Question SolutionДокумент12 страницBiocon Case Study Question Solutionbelinda abigaelОценок пока нет

- GE ChinaДокумент6 страницGE ChinajuliedehaesОценок пока нет

- Case Study 1Документ3 страницыCase Study 1pareek gopalОценок пока нет

- Strategic AlliancesДокумент27 страницStrategic AlliancesLitty KurianОценок пока нет

- Electro-Air Pad: Solar Charging StationДокумент28 страницElectro-Air Pad: Solar Charging StationBUSN460Оценок пока нет

- Slotwise CII NotesДокумент50 страницSlotwise CII NotesGCL GCLОценок пока нет

- Assignment 1 - International FinanceДокумент8 страницAssignment 1 - International FinanceKARTIK DABASОценок пока нет

- C K Prahalad Bottom of The PyramidДокумент10 страницC K Prahalad Bottom of The PyramidChetan MetkarОценок пока нет

- MarketingДокумент27 страницMarketingAkanksha AroraОценок пока нет

- General ElectricДокумент8 страницGeneral ElectricAnjali Daisy100% (1)

- Veggies Nearly Triple in Height Via Nanotechnology, With Poly's Help)Документ5 страницVeggies Nearly Triple in Height Via Nanotechnology, With Poly's Help)Lorraine Millama PurayОценок пока нет

- Frugal Engineering Part-1Документ26 страницFrugal Engineering Part-1azimsohel267452Оценок пока нет

- Gems Group5Документ4 страницыGems Group5saurav1202Оценок пока нет

- 1917138 (1)Документ5 страниц1917138 (1)makniazikhanОценок пока нет

- Explanations OF CASEДокумент3 страницыExplanations OF CASEblikerishabhОценок пока нет

- Chapter 10Документ56 страницChapter 10b1131916177Оценок пока нет

- Agricultural Biotechnology - Economic Growth Through New Products, Partnerships and Workforce DevelopmentДокумент276 страницAgricultural Biotechnology - Economic Growth Through New Products, Partnerships and Workforce DevelopmentSunny KimОценок пока нет

- The Innovation SandboxДокумент13 страницThe Innovation SandboxcandraОценок пока нет

- Case Study - Accelerating Drug DiscoveryДокумент10 страницCase Study - Accelerating Drug DiscoverythaynacanadaОценок пока нет

- Strategic ManagementДокумент5 страницStrategic ManagementTahseen ArshadОценок пока нет

- Market AnalysisДокумент6 страницMarket AnalysisMohamed AhmedОценок пока нет

- Project ReportДокумент7 страницProject ReportShahrooz JuttОценок пока нет

- Individual Assignment Example - Mindray Medical PDFДокумент10 страницIndividual Assignment Example - Mindray Medical PDFCheryl ShongОценок пока нет

- June 29, 2011: Volume 9, Number 5 Jobs Not Getting Done: Bold Approaches To InnovationДокумент8 страницJune 29, 2011: Volume 9, Number 5 Jobs Not Getting Done: Bold Approaches To InnovationMiltonThitswaloОценок пока нет

- Unit-14 Technological Environment AssessmentДокумент17 страницUnit-14 Technological Environment AssessmentPrasadakash Mantosh KumarОценок пока нет

- Project Management DriversДокумент3 страницыProject Management DriversNeeraj GargОценок пока нет

- Frugal InnovationДокумент20 страницFrugal InnovationGrace Triana PeranginanginОценок пока нет

- Quiz 2 Name: Hafiz Abdul MananДокумент2 страницыQuiz 2 Name: Hafiz Abdul Mananmanan abdulОценок пока нет

- Ee8061 Innovation and Technology Management Class Discusison 5Документ13 страницEe8061 Innovation and Technology Management Class Discusison 5davidbehОценок пока нет

- Bottom of The Pyramid MarketingДокумент26 страницBottom of The Pyramid MarketingAnam MalikОценок пока нет

- Ge Healthcare ThesisДокумент4 страницыGe Healthcare Thesisfc33r464100% (2)

- Molabola SocДокумент26 страницMolabola SocPaul KianОценок пока нет

- Article Review, The World Has Turned Upside DownДокумент5 страницArticle Review, The World Has Turned Upside DownPrakash ValiappanОценок пока нет

- Marketing Strategy of Consumer Durable CompaniesДокумент84 страницыMarketing Strategy of Consumer Durable CompaniesseemranОценок пока нет

- Marketing StrategyДокумент84 страницыMarketing StrategySantosh Dinesh100% (1)

- Unit - Iv Technological Environment Technological Environment in India Policy On Research and Development Patent Law Technology TransferДокумент31 страницаUnit - Iv Technological Environment Technological Environment in India Policy On Research and Development Patent Law Technology TransferRohini VyasОценок пока нет

- Sanuwave Investor Presentation.v5Документ36 страницSanuwave Investor Presentation.v5DougОценок пока нет

- The Emergence of Personalized Health TechnologyДокумент5 страницThe Emergence of Personalized Health TechnologyNoel S. De Juan Jr.Оценок пока нет

- Home Care in India - Kapil Khandelwal - EquNev CapitalДокумент1 страницаHome Care in India - Kapil Khandelwal - EquNev CapitalKapil KhandelwalОценок пока нет

- How GE Is Disrupting ItselfДокумент5 страницHow GE Is Disrupting ItselfRuchika SinhaОценок пока нет

- Sources: "Moving Up The Value Chain," Business Times, November 10, 2009 "Patient Guide," Parkway HealthДокумент5 страницSources: "Moving Up The Value Chain," Business Times, November 10, 2009 "Patient Guide," Parkway HealthHarsha tОценок пока нет

- ElectronicsДокумент33 страницыElectronicsmelihat dataОценок пока нет

- AnswersДокумент10 страницAnswersSaqib HanifОценок пока нет

- IH InstrumentationДокумент5 страницIH InstrumentationBharatiyaNaariОценок пока нет

- Case Study GEДокумент15 страницCase Study GEBaha'eddine TakieddineОценок пока нет

- Global Clinical Engineering 3-5-PB VOL 0 #1 - 2018Документ50 страницGlobal Clinical Engineering 3-5-PB VOL 0 #1 - 2018John Jairo CárdenasОценок пока нет

- Case Study EnvideaДокумент13 страницCase Study Envideakaushik_borgohainОценок пока нет

- For Immediate Release ContactДокумент5 страницFor Immediate Release ContactRavi DesaiОценок пока нет

- The Clean Tech Revolution (Review and Analysis of Pernick and Wilder's Book)От EverandThe Clean Tech Revolution (Review and Analysis of Pernick and Wilder's Book)Оценок пока нет

- Digital Health: Scaling Healthcare to the WorldОт EverandDigital Health: Scaling Healthcare to the WorldHomero RivasОценок пока нет

- Delivering Superior Health and Wellness Management with IoT and AnalyticsОт EverandDelivering Superior Health and Wellness Management with IoT and AnalyticsОценок пока нет

- Wearable Technology Trends: Marketing Hype or True Customer Value?От EverandWearable Technology Trends: Marketing Hype or True Customer Value?Оценок пока нет

- The Clean Tech Revolution: Winning and Profiting from Clean EnergyОт EverandThe Clean Tech Revolution: Winning and Profiting from Clean EnergyРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (2)

- Electronic Data Interchange (An in Depth Analysis of Technological and Security Issues)Документ30 страницElectronic Data Interchange (An in Depth Analysis of Technological and Security Issues)Mustafa HussainОценок пока нет

- Licensing Application PonitsДокумент5 страницLicensing Application PonitsMustafa HussainОценок пока нет

- Company Profile Voicetel LTDДокумент13 страницCompany Profile Voicetel LTDMustafa HussainОценок пока нет

- Ccna Voice With Voip: Course DurationДокумент2 страницыCcna Voice With Voip: Course DurationMustafa HussainОценок пока нет

- Tamanna Sharmin MumuДокумент4 страницыTamanna Sharmin MumuMustafa HussainОценок пока нет

- Tunazzina Islam: Career ObjectiveДокумент3 страницыTunazzina Islam: Career ObjectiveMustafa HussainОценок пока нет

- Dewan Mohammad Mahbubur RahmanДокумент3 страницыDewan Mohammad Mahbubur RahmanMustafa Hussain100% (1)

- Abu Zahed Jony: Career ObjectiveДокумент3 страницыAbu Zahed Jony: Career ObjectiveMustafa HussainОценок пока нет

- Industry-Academia-Bank Model: Presentation OnДокумент7 страницIndustry-Academia-Bank Model: Presentation OnMustafa HussainОценок пока нет

- Md. Mahbub UzzamanДокумент4 страницыMd. Mahbub UzzamanMustafa HussainОценок пока нет

- BoQ RelocationДокумент11 страницBoQ RelocationMustafa HussainОценок пока нет

- Form of Reduction of PBGДокумент1 страницаForm of Reduction of PBGMustafa HussainОценок пока нет

- Avid Final ProjectДокумент2 страницыAvid Final Projectapi-286463817Оценок пока нет

- DxDiag Copy MSIДокумент45 страницDxDiag Copy MSITạ Anh TuấnОценок пока нет

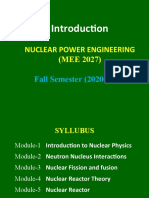

- Nuclear Power Engineering (MEE 2027) : Fall Semester (2020-2021)Документ13 страницNuclear Power Engineering (MEE 2027) : Fall Semester (2020-2021)AllОценок пока нет

- Ginger Final Report FIGTF 02Документ80 страницGinger Final Report FIGTF 02Nihmathullah Kalanther Lebbe100% (2)

- Industrial Machine and ControlsДокумент31 страницаIndustrial Machine and ControlsCarol Soi100% (4)

- Distribution BoardДокумент7 страницDistribution BoardmuralichandrasekarОценок пока нет

- IBPS Clerk Pre QUANT Memory Based 2019 QuestionsДокумент8 страницIBPS Clerk Pre QUANT Memory Based 2019 Questionsk vinayОценок пока нет

- Teks Drama Malin KundangДокумент8 страницTeks Drama Malin KundangUhuy ManiaОценок пока нет

- Villamaria JR Vs CAДокумент2 страницыVillamaria JR Vs CAClarissa SawaliОценок пока нет

- The Minimum Means of Reprisal - China's S - Jeffrey G. LewisДокумент283 страницыThe Minimum Means of Reprisal - China's S - Jeffrey G. LewisrondfauxОценок пока нет

- ThaneДокумент2 страницыThaneAkansha KhaitanОценок пока нет

- Schneider Contactors DatasheetДокумент130 страницSchneider Contactors DatasheetVishal JainОценок пока нет

- UnixДокумент251 страницаUnixAnkush AgarwalОценок пока нет

- List of Phrasal Verbs 1 ColumnДокумент12 страницList of Phrasal Verbs 1 ColumnmoiibdОценок пока нет

- Discovery and Integration Content Guide - General ReferenceДокумент37 страницDiscovery and Integration Content Guide - General ReferencerhocuttОценок пока нет

- Grade9 January Periodical ExamsДокумент3 страницыGrade9 January Periodical ExamsJose JeramieОценок пока нет

- Journal of Atmospheric Science Research - Vol.5, Iss.4 October 2022Документ54 страницыJournal of Atmospheric Science Research - Vol.5, Iss.4 October 2022Bilingual PublishingОценок пока нет

- Geometry and IntuitionДокумент9 страницGeometry and IntuitionHollyОценок пока нет

- LKG Math Question Paper: 1. Count and Write The Number in The BoxДокумент6 страницLKG Math Question Paper: 1. Count and Write The Number in The BoxKunal Naidu60% (5)

- Technical Data Sheet TR24-3-T USДокумент2 страницыTechnical Data Sheet TR24-3-T USDiogo CОценок пока нет

- Unit 1 - Lecture 3Документ16 страницUnit 1 - Lecture 3Abhay kushwahaОценок пока нет

- Explore The WorldДокумент164 страницыExplore The WorldEduardo C VanciОценок пока нет

- Object-Oriented Design Patterns in The Kernel, Part 2 (LWN - Net)Документ15 страницObject-Oriented Design Patterns in The Kernel, Part 2 (LWN - Net)Rishabh MalikОценок пока нет

- Holiday AssignmentДокумент18 страницHoliday AssignmentAadhitya PranavОценок пока нет

- LicencesДокумент5 страницLicencesstopnaggingmeОценок пока нет

- Adime 2Документ10 страницAdime 2api-307103979Оценок пока нет

- Microeconomics Term 1 SlidesДокумент494 страницыMicroeconomics Term 1 SlidesSidra BhattiОценок пока нет