Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Opponents of Egypt's Leader Call For Boycott of Charter Vote

Загружено:

Long Dong MidoИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Opponents of Egypt's Leader Call For Boycott of Charter Vote

Загружено:

Long Dong MidoАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Opponents of Egypts Leader Call for Boycott of Charter Vote

Tara Todras-Whitehill for The New York Times

Egyptian Republican guards stood in front of a barrier near the presidential palace in Cairo, as protesters demonstrated against President Morsi on Sunday.

By DAVID D. KIRKPATRICK Published: December 9, 2012

FACEBOOK TWITTER GOOGLE+ SAVE E-MAIL SHARE PRINT SINGLE PAGE REPRINTS

CAIRO The political crisis over Egypts draft constitution hardened on both sides on Sunday, as President Mohamed Morsi prepared to deploy the army to safeguard balloting in a planned referendum on the new charter and his opponents called for more protests and a boycott to undermine the vote.

Multimedia

Dueling Protests Continue in Cairo

Related

Times Topic: Egypt News Revolution and Aftermath Backing Off Added Powers, Egypts Leader Presses Vote(December 9, 2012)

Connect With Us on Twitter

Follow@nytimesworldfor international breaking news and headlines. Twitter List: Reporters and Editors

Thousands of demonstrators streamed toward the presidential palace for a fifth night of protests against Mr. Morsi and the proposed charter, and the president, a former leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, formally issued an order asking the military to protect such vital institutions and to secure the vote. With the decision to boycott the referendum, the opposition signaled that it had given up hope that it could defeat the draft charter at the polls, and had opted instead to try to undermine the referendums legitimacy. The call for new protests with major demonstrations expected at the presidential palace again on Tuesday and Friday ensures that questions about Egypts national unity and stability will continue to overshadow debate about the specific contents of the charter. Although international experts who have studied the draft say it is hardly more religious than Egypts old constitution, opponents say it fails to adequately protect individual rights from being constricted by a future Islamist majority in Parliament. Over the past two weeks, hundreds of thousands of people have poured into the streets to oppose the charter, crowds have attacked 28 Muslim Brotherhood offices and the groups headquarters, and at least seven people have died in clashes between Islamist and secular political factions. The opposition rejects lending legitimacy to a referendum that will definitely lead to more sedition and division, said Sameh Ashour, a spokesman for a coalition that calls itself the National Salvation Front. Holding a referendum in a state of seething and chaos, Mr. Ashour said, amounted to a reckless and flagrant absence of responsibility, risking driving the country into violent confrontations that endanger its national security.

Whether to ask voters to vote no or to stay home has been the subject of heated debate in opposition circles in the week since Mr. Morsi announced the referendum, to be held on Saturday. Now the question is whether opponents can translate the energy of the protests against the charter into more votes and seats in parliamentary elections that are expected to take place two months after the referendum. Both sides acknowledge that President Morsi, who belongs to the Muslim Brotherhoods political party, has hurt himself and his party politically with the act that first touched off the protests: a decree giving himself authoritarian powers and putting his decisions above the reach of judicial review until the new charter is passed. He suffered even more, they say, when the backlash against the decree and the new constitution led to a night of clashes between his Islamists supporters and their more secular opponents that left at least six dead and hundreds more injured. Mr. Morsi surprised his critics after midnight on Sunday by withdrawing almost all the provisions of his decree, a step he said he took on the recommendation of about 40 politicians and thinkers he convened on Saturday for a national dialogue meant to resolve the crisis. Leading opposition figures were invited to take part, but nearly all declined; according to a list broadcast on state television, most of the attendees were Islamists of various stripes, and the only prominent secular politician on hand was the former presidential candidate Ayman Nour. A spokesman for the group said at an authorized news conference that Mr. Morsi was issuing a new, more limited decree, giving immunity from judicial scrutiny only to his constitutional declarations, a narrow if hazily defined category of presidential actions. Steps he took under the previous decree would also be protected, including dismissal of the public prosecutor, who was appointed under the ousted former president, Hosni Mubarak. Through the spokesman for the national dialogue group, Mohamed Salim el-Awa, Mr. Morsi even signaled a willingness to allow his opponents and allies to negotiate a package of amendments to the constitution that all sides would agree to enact once the draft is approved. But Mr. Morsi did not concede to the oppositions main demand: to postpone the referendum long enough for an overhaul of the draft. Mohamed ElBaradei, the former diplomat who now acts as a coordinator of the secular opposition, was the first to fire back on Sunday, resorting again to the language of revolution.

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/10/world/middleeast/egypt-mohamed-morsiprotests.html?ref=world

19-12-2012 04:54PM ET

Presidential trials and errors

As Egypts first freely-elected president after last years 25 January Revolution, how is Mohamed Morsi faring, asks Dina Ezzat

Mohamed Morsi started this year as head of the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP), the political arm of the long-persecuted-but-popular Muslim Brotherhood. By the spring he was the back-up presidential candidate for the FJP and the Brotherhood. On 30 June, he was sworn in as the first-ever freely elected president in Egypts history. This week, as 2012 comes to an end, he is occupying a barricaded presidential palace whose back door is being kept ready for a possibly speedy exit. I really feel very sorry that I voted for him. It was a big mistake. He cheated us, said May, a doctor in her late 20s. Queuing up to participate in the referendum over the controversial draft constitution at one of the Heliopolis polling stations last Saturday, this veiled but carefully manicured lady said that it had been three hours since she had taken up her place in a long queue to vote no to the constitution. This is the least I could do to make up for the mistake of voting for anyone from the Muslim Brotherhood, she said. As she shared her frustration with other voters in-waiting, May received a call on her IPhone4. After a brief conversation marked with big smiles, contained laughter and a quick recitation of the Quranic verse in which the Almighty promises to defeat those who dont keep their promises, May hung up and announced the great news that her sister had said on behalf of her husband who had just come home. They got [Brotherhood leader] Khairat Al-Shater. They really gave him what he deserves [in terms of insults], she said to the queries of other voters. May shared news that was later all over YouTube. The strongman of the Muslim Brotherhood, its vice supreme guide and the original runner for the presidential elections whose legal status as a newly released prisoner blocked his campaign, had gone to vote at a school in Nasr City where he was met with anger by woman voters who shouted out, out with the liars at him. They lied to us. They promised to work to improve living conditions, security and traffic, but they did nothing. They promised to work in cooperation with other political forces, but they have been taking everything themselves, and they are trying to frighten us with the Salafis. But as we put them in, we will get them out, May said, supported by other women in the queue. Another veiled woman promised to continue the demonstrations until Morsi is forced out, with the help of the God Almighty. Sources with insights into the regular polling service of the Muslim Brotherhood say that there is a clear awareness in the group that Morsis popularity is declining sharply. It stands at around 20 per cent today, and they know it, said one source. Morsi was never a charismatic politician who solicited wide support. Within the ranks of the Muslim Brotherhood itself, he was never perceived to be anywhere near Al-Shater, who is said by his supporters, like his critics, to be charismatic, or like Abdel-Moneim Abul-Fotouh, a former Brotherhood leader who now heads the Strong Egypt Party and is known to have enormous respect within this oldest political Islam group, especially among the younger generation. Among the five key presidential candidates, who included Morsis round-two adversary Ahmed Shafik, the last prime minister of the regime of ousted former president Hosni Mubarak, Nasserist Hamdeen Sabahi, Amr Moussa, a former foreign minister and Arab League secretary-general, and Khaled Ali, a prominent labourers rights lawyer, Morsi was perceived to have the lowest presence indicator, leading some commentators to suggest that no matter what the influence of the Muslim Brotherhood was like on the ground it would be difficult to get this very square, even if good-hearted and hardworking, politician into the presidential palace.

Yet, it happened. Morsis success in the presidential elections was not about Morsi himself or his platform, but about the strong influence of the Muslim Brotherhood. His victory was that of the Muslim Brotherhood, said Hassan Abu Taleb, a political analyst. In round one of the presidential elections held in May, Morsi got around five million out of a total of some 25 million votes cast. During the few weeks leading to round two of the elections, Morsi solicited the support of voters from across the political spectrum. In a meeting at the Fairmont Hotel in Heliopolis, Morsi received representatives of diverse political forces and promised consensual and participatory rule in return for their support. Last June, Morsi was sworn in as president, assuming office against the backdrop of a constitutional declaration issued by the transitional ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), which divided the rule of the country between the army leadership and the elected president. This dual rule was later eliminated in mid-August, when the president issued his own presidential declaration to remove the top army leadership and introduce his own team of Islamist-oriented generals in the wake of a breakdown in security in Sinai. When he did that we all supported him, said Mariam, a pharmacist in her 30s. Speaking after having voted no to the constitution, this veiled young woman said that she had voted for Morsi in the second round of the presidential elections after having voted for Khaled Ali in the first. I voted for him because I was afraid that if Shafik were president there would be repression against his opponents and political activists. But now Morsi is doing what I feared Shafik would have done. It is really very sad, she said. During the last six weeks, Morsi has been suffering from political hiccups. These started with the constitutional declaration announced by the presidency on 22 November that gave the president close to full control over all state powers. This particularly infuriated a large part of the countrys judiciary, whose leadership is associated directly or indirectly with the ousted Mubarak regime. The constitutional declaration prompted widespread demonstrations against it, some spontaneous and others more well-organised. The result was bloody confrontations between supporters, massed under the Muslim Brotherhood and its Salafi allies, and opponents that included everyone from Shafik supporters to independent Islamist activists, along with leftists and those who are apolitical. On the first day of the demonstrations, Morsi was forced to exit out of the presidential palace ahead of a massive demonstration. The president was said to have been rushed out of the backdoor of the presidential palace. On the second day, eight activists were announced as having been killed during the demonstrations. In search of an exit, Morsi then forced ahead the vote over a controversial draft of the new constitution that had been abruptly finalised by a drafting committee stripped of all non-Islamist members during its last phase. That was an attempt to fix one big mistake with another mistake it accentuated the polarisation that society had fallen into between those who oppose Morsi for a wide range of reasons and those who support him because they subscribe to the political Islam camp, said Abu Taleb. In the midst of this political quagmire that he had landed in while trying to defuse what his aides say was a conspiracy by his political adversaries against the president, Morsi was caught between his now rapidly resigning aides, who were pushing for reconciliatory moves, and the leadership of the Muslim Brotherhood, which according to sources within the group was blaming the president for his poor political performance and giving him contradictory advice on how to run the political show and attend to economic decision-making. The latter included the release, and then the freeze, of a decision to increase the prices of some commodities and services in what prompted the scepticism of an even wider segment of society. At the same time, there was criticism by Brotherhood figures and associated clerics against the Copts and the followers of other churches in Egypt for their opposition to the draft constitution, thus prompting the antagonism of yet another segment of society that was already apprehensive about its future. Morsi had discredited himself on so many levels, said Emad Gad, a political commentator and activist. According to Gad, Morsi, who on the eve of round two of the presidential elections had promised to be president for all Egyptians, a promise reiterated following his victory, had discredited himself as an unbiased president. He acted as the president of the Islamists, the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafis, Gad said. One of the remarks that many made on Saturday during the first round of the referendum on the constitution in 10 of the 27 Egyptian governorates was that Morsi, who had started his presidency by going to Tahrir Square to address all those present, even if they had been predominantly Islamist, had now failed to revisit the square where the 25 January Revolution took place. Instead, he had addressed only a group of his supporters next to the presidential palace in Heliopolis. Morsis reserved public presence has been getting more obvious by the week. The president, who went for his first Friday prayers at a crowded and hard-to-secure Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo to be met with genuine signs of support from ordinary citizens, seemed perplexed last Friday about where to go to prayers to avoid the kind of attacks he was subjected to two weeks ago at a neighbourhood mosque, according to a security source. From the first Friday in July, right after his inauguration, to last Friday, Morsi has acted not just as a strictly Islamist president, but also as a president who does not keep his promises and who fails to streamline state affairs, in the eyes of many commentators. The president made several promises about having an independent figure to head his government and having assistants and cabinet members that represented the entire society and above all to improve the quality of life for all Egyptians, but none of this has happened. Even if we could argue like those who say it is a very difficult task to fix the economy or the traffic, we could still say that he has no excuse for breaking his promises regarding a participatory approach to ruling, Gad said. He said that Morsi had his eyes on the Muslim Brotherhood and Salafis alone and that consequently he had lost all support outside these two groups. Morsi is for sure losing his legitimacy, Gad added. It has become clear that he is not ruling alone and that his decisions are made upon the directives of Al-Shater and of the supreme guide of the Muslim Brotherhood. Even then, he is not doing a good job. For Abu Taleb, who had not supported Morsi during the elections, Morsi had committed the unforgivable error of betraying the trust of the nation in favour of the approval of the Islamists. Either his presidency would come to an abrupt end, or he would continue his term in continued political turmoil, Abu Taleb said. When Morsi goes, the chances of political Islam as a whole holding onto power would exit from the stage for a long while to come, he added. Leftist activist Wael Khalil, who supported Morsi during the second round of the elections, does not argue that the president has not committed errors during his first six months in office. Nor does he necessarily excuse any of them. However, Khalil said that he did not think that Morsis errors were as serious as some have made out. Morsi could still do a U-turn, he suggested. So far, we have seen a mediocre performance from the Muslim Brotherhood, especially during the first half of the year before the elected parliament was dissolved, Khalil said. The Islamists had enjoyed close to two-thirds of the seats in a parliament elected around this time last year and dissolved during the early days of summer because of the unconstitutional nature of the electoral law. During its early sessions, the parliament failed to impress, and people complained that it was engrossed in irrelevant debates and was failing to adopt legislation that could serve the much-needed socio-economic reforms. At the same time, it was failing to pursue the rights of the martyrs who had died during the revolution.

During the second half of the year, Khalil said, Morsi has started his presidency without a parliament amidst hopes that he would cease the moment he went beyond the lines of his traditional constituency and those of the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist quarters. But unfortunately he did not. It was not that difficult. He could have reached out to the people even if at the expense of the consent of the Muslim Brotherhood leadership, and he could have garnered wider public support that would have been more fortifying than any Brotherhood organisational skills. But unfortunately, and typically of the Muslim Brotherhoods style, he failed to take account of the masses. Today, despite the growing scepticism, things are not too late for Morsi, Khalil said. The vast majority of people want Morsi to fix his performance and stay on as president, rather than wanting him to go. That would mean another long [and open-ended] political process, he said. The recipe for the reform, some might even say salvaging, of Morsis presidency is not too complicated, according to Khalil. He needs to adopt a more participatory approach in which he includes the views of other political forces in practice and not just in theory. According to Khalil, Morsi also needs to convince the Muslim Brotherhood to refrain from adopting the kind of dominating techniques enforced during the Mubarak regime and that eventually led to the fall of Mubarak himself. Above all, Khalil insisted, Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood needed to go beyond the sentiment of self-victimisation that could make alleged or possible adversaries conspiracies self-fulfilling prophecies. There will always be problems, but if he has the people with him, and not just his group, he can find a way to attend to these problems. I am convinced that angry as people are today with his performance and the polarisation of society, they will still give him the benefit of the doubt, even if as reluctantly as in the second round of the elections, Khalil concluded.

http://weekly.ahram.org.eg/News/615/17/Presidential-trials-and-errors.aspx

Вам также может понравиться

- Egyptian Vote Time ArticleДокумент3 страницыEgyptian Vote Time ArticleHayleyОценок пока нет

- 02.07.13 Morsi Faces Ultimatum As Allies Speak of Military Coup'Документ5 страниц02.07.13 Morsi Faces Ultimatum As Allies Speak of Military Coup'anirudhadapaОценок пока нет

- The Revolution Will Not Be Marginalized: Max Blumenthal Reports From Egypt's Counter-Counter-RevolutionДокумент4 страницыThe Revolution Will Not Be Marginalized: Max Blumenthal Reports From Egypt's Counter-Counter-RevolutionPando DailyОценок пока нет

- 0307 Cap 014Документ1 страница0307 Cap 014bernicetsyОценок пока нет

- Traub, James. 2007. "Islamic Democrats - " New York Times Magazine - 44-49Документ21 страницаTraub, James. 2007. "Islamic Democrats - " New York Times Magazine - 44-49Rommel Roy RomanillosОценок пока нет

- Mansour in Reconciliation EffortsДокумент2 страницыMansour in Reconciliation EffortsGhulam Hassan KhanОценок пока нет

- 07-02-11 - Protests Demanding Mubarak's Resignation Grow Stronger Despite Some Government ConcessionsДокумент8 страниц07-02-11 - Protests Demanding Mubarak's Resignation Grow Stronger Despite Some Government ConcessionsWilliam J GreenbergОценок пока нет

- 'Not Even The Pharaohs Had So Much Authority': Elbaradei Speaks Out Against MorsiДокумент2 страницы'Not Even The Pharaohs Had So Much Authority': Elbaradei Speaks Out Against MorsiMohamed AlaaОценок пока нет

- 19-07-13 The Grand Scam: Spinning Egypt's Military CoupДокумент10 страниц19-07-13 The Grand Scam: Spinning Egypt's Military CoupWilliam J GreenbergОценок пока нет

- Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st CenturyОт EverandEvidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st CenturyОценок пока нет

- Guccifer Drumheller Blumenthal Memos PDFДокумент47 страницGuccifer Drumheller Blumenthal Memos PDFUploaderОценок пока нет

- Turc Des Affairs EtrangersДокумент3 страницыTurc Des Affairs EtrangersOğuzhan ÖztürkОценок пока нет

- Muslim Brotherhood Is Considered As The WorldДокумент12 страницMuslim Brotherhood Is Considered As The WorldMUHAMMED TcОценок пока нет

- Arab Revolution PDFДокумент36 страницArab Revolution PDFAsad IbrahimОценок пока нет

- In 2013, Rise of The Right in Elections Across The MideastДокумент8 страницIn 2013, Rise of The Right in Elections Across The MideastThe Wilson CenterОценок пока нет

- mg342 AllДокумент24 страницыmg342 AllsyedsrahmanОценок пока нет

- Egypt Position PaperДокумент7 страницEgypt Position PaperFIDHОценок пока нет

- The Dawn Call For Imposing Sanctions On Myanmar: Iran Agenda Faces Realities' at World GatheringДокумент4 страницыThe Dawn Call For Imposing Sanctions On Myanmar: Iran Agenda Faces Realities' at World Gatheringsinghsundar334Оценок пока нет

- Egyptians Bewildered Over BO Support For MBДокумент4 страницыEgyptians Bewildered Over BO Support For MBVienna1683Оценок пока нет

- 03-07-08 CSM-Iran Debate - Who Owns The Revolution by Scott PДокумент3 страницы03-07-08 CSM-Iran Debate - Who Owns The Revolution by Scott PMark WelkieОценок пока нет

- Liberian Daily Observer 02/03/2014Документ16 страницLiberian Daily Observer 02/03/2014Liberian Daily Observer NewspaperОценок пока нет

- Thousands Protest Military Rule in Egypt After Muslim Brotherhood BanДокумент2 страницыThousands Protest Military Rule in Egypt After Muslim Brotherhood BanShane MishokaОценок пока нет

- The Irresistible Rise of The Muslim Brothers Fawas Gerges Published 28 November 2011Документ14 страницThe Irresistible Rise of The Muslim Brothers Fawas Gerges Published 28 November 2011Aşır Yüksel KayaОценок пока нет

- Nadia Khomami @nadiakhomamiДокумент3 страницыNadia Khomami @nadiakhomamiGn H Gil MejiaОценок пока нет

- Egypt: Road To VictoryДокумент11 страницEgypt: Road To VictoryMohammad AkmalОценок пока нет

- Egypt Crowds Unmoved by Mubarak's Vow Not To Run: Tahrir SquareДокумент4 страницыEgypt Crowds Unmoved by Mubarak's Vow Not To Run: Tahrir SquareGerardoОценок пока нет

- US Bankrolled Anti-Morsi ActivistsДокумент8 страницUS Bankrolled Anti-Morsi Activistsh86Оценок пока нет

- Iran's Future Scenarios: An Illustrative Discussion of Multiple Mental ModelsДокумент16 страницIran's Future Scenarios: An Illustrative Discussion of Multiple Mental Modelspayamkhan2010Оценок пока нет

- Some Syrians Vote, As Others Are AttackedДокумент5 страницSome Syrians Vote, As Others Are AttackedcocoopuiОценок пока нет

- MB Project NJCUДокумент5 страницMB Project NJCUegyptnjcuОценок пока нет

- I030 CFC Medbasin News-Infocus (13-Nov-12)Документ2 страницыI030 CFC Medbasin News-Infocus (13-Nov-12)Robin Kirkpatrick BarnettОценок пока нет

- Martin/Zimmerman. As Noted A Few Hours Ago, Following Imposition of Enormous SocialДокумент4 страницыMartin/Zimmerman. As Noted A Few Hours Ago, Following Imposition of Enormous SocialRobert B. SklaroffОценок пока нет

- Debkafile Exclusive Report: June 13, 2012Документ2 страницыDebkafile Exclusive Report: June 13, 2012api-154388419Оценок пока нет

- Liberian Daily Observer 01/27/2014Документ18 страницLiberian Daily Observer 01/27/2014Liberian Daily Observer NewspaperОценок пока нет

- Unit 2 Portfolio NewsletterДокумент2 страницыUnit 2 Portfolio Newsletterapi-304312954Оценок пока нет

- Hillel Fradkin On Arab DemocracyДокумент10 страницHillel Fradkin On Arab DemocracyMáté MátyásОценок пока нет

- Morsi's Ouster Shakes Egypt and The Region: Middle East in FocusДокумент2 страницыMorsi's Ouster Shakes Egypt and The Region: Middle East in FocusCanna IqbalОценок пока нет

- Eric Trager and Marina Shalabi - in Egypt, The Muslim Brotherhood's New Leaders Turn Revolutionary To Stay RevelantДокумент6 страницEric Trager and Marina Shalabi - in Egypt, The Muslim Brotherhood's New Leaders Turn Revolutionary To Stay RevelantDhruvNagpalОценок пока нет

- The Rise and Fall of Political Islam and Democracy in The Middle EastДокумент4 страницыThe Rise and Fall of Political Islam and Democracy in The Middle EastRizky AmaliaОценок пока нет

- The Hindu Imp. News Feb. 12th 2012Документ7 страницThe Hindu Imp. News Feb. 12th 2012Baljit DochakОценок пока нет

- Global CrisisДокумент12 страницGlobal CrisisDavid GadallaОценок пока нет

- The Second, People-Led RevolutionДокумент45 страницThe Second, People-Led RevolutionDr. Iman BibarsОценок пока нет

- A Tunisian-Egyptian Link That Shook Arab History: FacebookДокумент7 страницA Tunisian-Egyptian Link That Shook Arab History: FacebookWaleed FekryОценок пока нет

- Britain's Deficient Democracy: A Pledge of AllegianceДокумент6 страницBritain's Deficient Democracy: A Pledge of Allegiancehati1Оценок пока нет

- Bahrain Sunnis Defend MonarchyДокумент2 страницыBahrain Sunnis Defend MonarchyMissKuoОценок пока нет

- Bahrain Media Roundup: Read More Read MoreДокумент2 страницыBahrain Media Roundup: Read More Read MoreBahrainJDMОценок пока нет

- Egypt's Also RanДокумент4 страницыEgypt's Also RanSheriff SammyОценок пока нет

- Tracking The: "Arab Spring"Документ15 страницTracking The: "Arab Spring"Marcos Inzunza TapiaОценок пока нет

- CRS Report For Congress: Egypt: 2005 Presidential and Parliamentary ElectionsДокумент6 страницCRS Report For Congress: Egypt: 2005 Presidential and Parliamentary ElectionsFabio MetzgerОценок пока нет

- Westminster Egypt Delegation Press ReleaseДокумент3 страницыWestminster Egypt Delegation Press ReleaseSUAusEdОценок пока нет

- Marsi Govt and Our Doublr StandardsДокумент2 страницыMarsi Govt and Our Doublr StandardsEngr TariqОценок пока нет

- Middle East Policy CouncilДокумент9 страницMiddle East Policy CouncilMuhammedОценок пока нет

- Islamists and Human Rights in Egypt andДокумент28 страницIslamists and Human Rights in Egypt andJavid HashmzaiОценок пока нет

- The 2018 Egyptian Elections and Lessons-71842622Документ4 страницыThe 2018 Egyptian Elections and Lessons-71842622Fedia GasmiОценок пока нет

- DD309 ATMA2016 FirstДокумент4 страницыDD309 ATMA2016 FirstLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Module 1 Introduction and Business Start-UpДокумент25 страницModule 1 Introduction and Business Start-UpLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Quality As Value-Adding Management Concept:: IKEA Supplier Quality AssuranceДокумент16 страницQuality As Value-Adding Management Concept:: IKEA Supplier Quality AssuranceLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- OM - Chp. 1Документ31 страницаOM - Chp. 1Long Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Operations Management. - CH 1: 1-Discuss The Concept of Operations Management and Operations Function?Документ11 страницOperations Management. - CH 1: 1-Discuss The Concept of Operations Management and Operations Function?Long Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- T306A TMA Fall 2016Документ8 страницT306A TMA Fall 2016Long Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1: How To Design A Language?Документ2 страницыChapter 1: How To Design A Language?Long Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- TMA Cover Form Faculty of Language Studies AA100A: The Arts Past and Present IДокумент4 страницыTMA Cover Form Faculty of Language Studies AA100A: The Arts Past and Present ILong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Lecture 1 EntrepreneurshipДокумент35 страницLecture 1 EntrepreneurshipLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Major/ Omar Alnufais Military Number:-37465Документ4 страницыMajor/ Omar Alnufais Military Number:-37465Long Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Major/ Omar Alnufais Military Number:-37465Документ4 страницыMajor/ Omar Alnufais Military Number:-37465Long Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Impact Test: ObjectiveДокумент4 страницыImpact Test: ObjectiveLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Tensile Test: ObjectiveДокумент3 страницыTensile Test: ObjectiveLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Impact Test: ObjectiveДокумент3 страницыImpact Test: ObjectiveLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- ExperimentДокумент3 страницыExperimentLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Samsung Case StudyДокумент17 страницSamsung Case StudyLong Dong Mido100% (1)

- Tensile Test: ObjectiveДокумент3 страницыTensile Test: ObjectiveLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Tourism in KuwaitДокумент16 страницTourism in KuwaitLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Tensile Test: ObjectiveДокумент4 страницыTensile Test: ObjectiveLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Hillary Clinton Assails James Comey, Calling Email Decision Deeply Troubling'Документ3 страницыHillary Clinton Assails James Comey, Calling Email Decision Deeply Troubling'Long Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Manchester United News: Jose Mourinho Could Face Potential Stadium BanДокумент4 страницыManchester United News: Jose Mourinho Could Face Potential Stadium BanLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- A Linguistic Toolkit Chapters 7-9Документ20 страницA Linguistic Toolkit Chapters 7-9Long Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Lebanese Lawmakers Pick Hezbollah-Ally Michel Aoun To End Presidential LogjamДокумент4 страницыLebanese Lawmakers Pick Hezbollah-Ally Michel Aoun To End Presidential LogjamLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- Iraqi Forces Prepare To Break Into Mosul in Battle Against Islamic StateДокумент4 страницыIraqi Forces Prepare To Break Into Mosul in Battle Against Islamic StateLong Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- U214A Class 1Документ45 страницU214A Class 1Long Dong MidoОценок пока нет

- 5 Market Segmentation Targeting and PosiДокумент24 страницы5 Market Segmentation Targeting and PosiLong Dong Mido100% (1)

- Mun Resolution Israel PalestineДокумент2 страницыMun Resolution Israel Palestineapi-29836926450% (6)

- List of Hospitals For All Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Lebanon (Please Note That Some Changes in The List May Occur)Документ2 страницыList of Hospitals For All Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Lebanon (Please Note That Some Changes in The List May Occur)AliОценок пока нет

- Badge Lists NamesДокумент1 страницаBadge Lists NamesNawaf Bin HadbaОценок пока нет

- English Report Khadija BouzelmatДокумент3 страницыEnglish Report Khadija BouzelmatKhadija BouzelmatОценок пока нет

- Latihan NewsДокумент3 страницыLatihan Newsfadilvalderama404Оценок пока нет

- Unofficial Members of The National Transitional Council of LibyaДокумент2 страницыUnofficial Members of The National Transitional Council of Libyaapi-112102714Оценок пока нет

- Israel Palestine IsueДокумент11 страницIsrael Palestine IsueAdira ReeОценок пока нет

- Azimuth Al MapДокумент1 страницаAzimuth Al MapSaiful Rizam TangoxraylimaОценок пока нет

- Arab-Israeli WarДокумент29 страницArab-Israeli WarAykut ÜçtepeОценок пока нет

- The Main Lebanese Political PartiesДокумент15 страницThe Main Lebanese Political PartiesDeen Sharp100% (4)

- OGLES 123 (Jayapal)Документ3 страницыOGLES 123 (Jayapal)Michael GinsbergОценок пока нет

- QAI GCC Iran Trade Fact SheetДокумент2 страницыQAI GCC Iran Trade Fact SheetQatar-America InstituteОценок пока нет

- M.yasser.s (24) X Mipa 3Документ3 страницыM.yasser.s (24) X Mipa 3Muhammad YassersaputroОценок пока нет

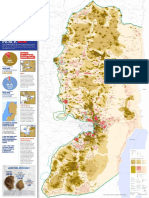

- Settlements Map en 2023Документ2 страницыSettlements Map en 2023Parag Ekbote100% (1)

- Bahrain Government Ministers From Al Khalifa Royal Family 20 May 2011 TextДокумент1 страницаBahrain Government Ministers From Al Khalifa Royal Family 20 May 2011 TextxxKallistAxxОценок пока нет

- Leila KhalidДокумент1 страницаLeila KhalidSeema SindhuОценок пока нет

- Israel Gaza War: History of The Conflict Explained - BBC NewsДокумент2 страницыIsrael Gaza War: History of The Conflict Explained - BBC NewsAnne ForgetableОценок пока нет

- 22.23 Israel - Palestine Web QuestДокумент3 страницы22.23 Israel - Palestine Web QuestSasha ShishkinОценок пока нет

- Governing Gaza After The War The Regional Perspectives - Carnegie Endowment For International PeaceДокумент8 страницGoverning Gaza After The War The Regional Perspectives - Carnegie Endowment For International PeacecyntiamoreiraorgОценок пока нет

- Vocab Offical Makrs FinalДокумент2 страницыVocab Offical Makrs FinalAmal BologniniОценок пока нет

- Draft Resolution 1.1: Special Political and Decolonization CommitteeДокумент3 страницыDraft Resolution 1.1: Special Political and Decolonization CommitteeMudassir AyubОценок пока нет

- Iraq Offers Deal To Quit Kuwait U.S. Rejects It, But Stays 'Interested' (NASSAU AND SUFFOLK Edition)Документ2 страницыIraq Offers Deal To Quit Kuwait U.S. Rejects It, But Stays 'Interested' (NASSAU AND SUFFOLK Edition)phooey108Оценок пока нет

- Exchange Rates The Libya ObserverДокумент1 страницаExchange Rates The Libya ObserverMOHA MEDОценок пока нет

- List of Universities and Colleges in Saudi Arabia: University/College Website Foundati On City Riyadh ProvinceДокумент3 страницыList of Universities and Colleges in Saudi Arabia: University/College Website Foundati On City Riyadh ProvinceAbdullah Al SajibОценок пока нет

- Dubai Companies Addresses For Mega ProjectsДокумент3 страницыDubai Companies Addresses For Mega Projectsmuhammad waqas arshadОценок пока нет

- Map - Clean Map of Israel, Gaza, and West BankДокумент1 страницаMap - Clean Map of Israel, Gaza, and West Bankwildguess1Оценок пока нет

- I Read and Do 1 Yara Juda - TasksДокумент2 страницыI Read and Do 1 Yara Juda - TasksLylia Rose100% (1)

- Israel and Palestine ConflictsДокумент4 страницыIsrael and Palestine ConflictsgarryОценок пока нет

- Name Position Phoneفتاهلا / Mobileلاقنلا / Email/ليميلاا Photo/ ةروصلا ةفصلا مــــسلاا Omar JelbanДокумент4 страницыName Position Phoneفتاهلا / Mobileلاقنلا / Email/ليميلاا Photo/ ةروصلا ةفصلا مــــسلاا Omar Jelbanapi-65585217Оценок пока нет

- Palestinian Non-Violent Resistance To Occupation Since 1967Документ12 страницPalestinian Non-Violent Resistance To Occupation Since 1967Centro Culturale Islamico Al Farouq PadovaОценок пока нет