Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Effects of Multimedia Stories of Deaf or Hard-of-Hearing Celebrities On The Reading Comprehension and English Words Learning of Taiwanese Students With Hearing Impairment

Загружено:

lhendheiОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Effects of Multimedia Stories of Deaf or Hard-of-Hearing Celebrities On The Reading Comprehension and English Words Learning of Taiwanese Students With Hearing Impairment

Загружено:

lhendheiАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp.

91-105, 2009

The Effects of Multimedia Stories of Deaf or Hard-of-Hearing Celebrities on the Reading Comprehension and English Words Learning of Taiwanese Students with Hearing Impairment

JING-MING JU*

Department of Early Childhood Education, Asia University, Taiwan

ABSTRACT

The main purpose of this study was to improve the reading comprehension and to increase the English vocabulary of students with hearing impairment; with the sub-goal of encouraging them to strive for success. To overcome the reading difficulty of students with hearing impairment, the author developed a multimedia program with main ideas, graphic organizers and English key words integrated to make reading a more exciting, pleasant and understandable experience. The multimedia stories of Taiwanese deaf or hard-of-hearing celebrities included a famous model, a professor, a teacher, an athlete, a computer programmer, an illustrator, an insurance agent and a deaf leader. In the main idea identification, English word pronunciation, recognition, listening comprehension and lip-reading, post-test scores were significantly higher than pre-test scores. Students also found these stories encouraging and hoped they could have more similar multimedia stories. Key words: multimedia, hearing impairment, reading comprehension, English learning.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the U.S., even after 30 years of educational innovations, most deaf children did not read on grade level (Luetke-Stalhman & Nielson, 2003). Kelly (2003) indicated that low reading comprehension persisted among deaf readers, and low automaticity in recognizing words and parsing sentence patterns was a significant source of the difficulty. The Gallaudet Research Institute (1996) reported that the median reading level for deaf 18-year-olds nationwide was a 3.9 grade equivalent. A study by Flaherty and Moran (2004) seemed to imply that memory spans were similar for deaf and hearing participants for words constructed from Chinese characters, which are logographs. However, Taiwanese deaf students may not have benefited much from the use of Chinese characters. In Taiwan, Lin and Lee (1987) found the reading ability of 7th to 9th grade students in deaf schools was equivalent to 1.5 grade level, and the reading ability of 10th to 12th grade students in deaf schools was equivalent to 2.2 grade level. Chang (1987) found the reading ability of elementary pupils with severe hearing impairment lagged behind their hearing peers by 2.2 grade levels. Two years later, Chang (1989) found the reading ability of 3rd to 6th grade pupils with hearing impairment was equivalent to 1.7, 2.1, 2.5 and 3.6 grade level respectively. Tsai (1994) studied 287 middle-school students with hearing impairment in central and southern Taiwan, and found they lacked learning strategies, especially reading comprehension strategy. Chi (2000) further

*

E-mail: Jjm3222@gmail.com

91

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

studied hearing-impaired students reading comprehension ability and found they were lagging behind in understanding basic facts, making inference, comparing and analyzing and retrieving main ideas. The lag occurred both in narrative and expository text. According to a survey conducted by the Department of Human Development and Family at National Taiwan Normal University, among a random sample of 4,942 high school students rating the helpfulness of twenty-five subjects, English was rated more helpful to life than Chinese, the official language, by one place (Chou, 2006). This survey was extensive as it sampled thirty-three high schools around Taiwan. Although English is a foreign language in this country, it has found its way into almost every corner of Taiwan in this era of the global village. Professionals seem to have assumed that students with hearing impairment inevitably will have problems learning a phonetic language like English. However, it is still necessary for students with hearing impairment in Taiwan to learn some basic English for their everyday life. With recent advances in technology, hearing aids and cochlear implants may enhance their phonologic awareness. Moreover, computers are especially suitable for people with hearing impairment as their learning primarily depends upon visual information. Computers are mostly visual and highly interactive, thus they fit the students learning style perfectly. To overcome the reading difficulties and to increase the English vocabulary of students with hearing impairment, the author developed a multimedia program with main ideas, graphic organizers and English key words integrated to make reading a more exciting, pleasant and understandable experience.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Computer Assisted Instruction for Students with Hearing Impairment Computers are especially suitable for students with hearing impairment, as their learning primarily depends upon visual information. Computers are mostly visual and very interactive, thus fitting the students learning style perfectly. Lindstrand (2001) surveyed sixteen parents of children with hearing impairment about the importance of computers, and the parents pointed out that computers were most helpful for language development, word recognition and concept development through their visual support. Barker (2003) conducted an outcomes assessment to determine the effectiveness of a computer-based vocabulary tutor in an elementary auditory/oral program. Participants were nineteen children, sixteen profoundly deaf and three hearing. Through audiovisual reception, children memorized up to 218 new words for household items. After four weeks, most students retained more than half of the new words. Xin, Glaser and Rieth (1996) described video-based vocabulary lessons that they used with ten fourth-grade students enrolled part-time in a special education resource program serving students with learning disabilities. The results indicated that on a six-week review test, students correctly obtained the meanings of 60% of the new target words. This represented an improvement of 27% over the scores that the students retained when

92

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

non-video-based instructional procedures were used. In addition, 95% of the students reported that they enjoyed learning new vocabulary words with the help of video presentations. Andrews & Jordan (1998) believed multimedia applications are especially useful for deaf children because video dictionaries of sign language can be built right into the stories. They set up a multimedia laboratory and had the staff develop scripts and multimedia stories centering on the Mexican-American culture. They used the internet to research their stories and then put the stories on the Web. Gentry, Chinn and Moulton (2005) studied the effects of multimedia computers on the reading achievement of twenty-six students with hearing impairment. The experiment consisted of three kinds of intervention: text, text and graph, text and video of sign language. The results indicated that pure text produced the poorest performance in reading comprehension by the students. Multimedia presentation produced better performance in reading comprehension. Prinz, Nelson, Geysels and Willems (1993) studied the effects of multimedia computers on deaf childrens reading and writing; the subjects were ten children with severe and profound hearing impairment. They received twenty minutes of training on computers each week. After ten weeks, the post-test score on sentence matching, reading comprehension had improved by more than 50%, and their reading fluency, speed, and accuracy were significantly better than pre-test. Volterra (1995) used interactive multimedia software to teach twelve deaf students (aged six to sixteen) Italian by Italian sign language. All twelve students benefited from this software. Many learning and reading strategies can be integrated into computer software, which will attract students attention and give them a successful experience. Gillespie and Twardorsz (1997) used story books to enrich deaf childrens vocabulary, and the children became more involved in the reading process when the story telling used more expressive and interactive strategies. Hanson and Padden (1989) developed an interactive video disc program to teach deaf students English; the program included five activities: watch the story, read the story, answer questions about the story, write a story, and write captions for the story. Copra (1990) also developed an interactive video disc program to teach deaf pupils English; they read stories, watched videos of sign language stories, learned a series of words, and wrote captions for videos of sign language stories. When Fogel (1990) integrated the principle of direct instruction into interactive reading software, she found that computer visual graphic and control system could improve deaf students language ability, including vocabulary, syntax, and inference. Mayer and Lee (1995) studied two groups of 158 fourth, fifth and sixth grade reading deficient student, who were randomly assigned to either an average-paced closed-caption video, a slow-paced closed-captioned video, or printed text with no video, serving as a control measure. Results indicated significantly more learning occurs for those students using captioned video compared to those having traditional print materials. Additionally, students assigned to the slow-paced prompt rate retained significantly more information than those having the average-paced captioning. Results suggested educators could better help reading deficient students by choosing a captioned-video curriculum rather than traditional print materials. Higgins, Boone and Lovitt (1996) found that students who had access to hypermedia study guides exhibited better information retention than

93

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

students who did not use the hypermedia study guides. Hillinger (1994) indicated that ordinary printed text could not provide reading-disabled students with the necessary help, but hypermedia computers could compensate the basic deficiency of poor readers. He called this kind of computer hypermedia text responsive text. Responsive text provided voice or graphics to help word recognition, background information and notes to help comprehension, and interactive questions to monitor reading process. Students using the responsive text had their reading comprehension improved more than ordinary text or less interactive reading program could have. Students with hearing impairment often quit or give up when they meet unfamiliar words or fail to comprehend the sentences. This will form a vicious circle. The more they dislike reading, the worse their reading ability will become. Hypermedia text can help them understand unfamiliar vocabulary through graphic or video. Thus, this study developed a multimedia program with hyperlinked English key words, in addition to graphic organization and main ideas. 2.2 Main Idea and Graphic Organization Kelly, Albertini and Shannon (2001) indicated that standardized reading test scores of deaf college students were not necessarily clear indicators of their functional comprehension of authentic text. Their data showed that the students in both the higher-level and lower-level reading groups did not identify the main idea of the passage from Science Watch (on methane gas and air quality) or answer the related content questions correctly. van den Broek, Lynch, Naslund, Ievers-Landis and Verduin (2003) investigated the development of readers ability to identify main ideas in narrative texts. Their results revealed that even the youngest students were able to identify the main ideas, but they did so less consistently than did older students. Burke (2003) presented the Main Idea Organizer (MIO) to help students who may struggle with writing, reading and thinking and described many different ways the MIO was used. Stevens (1986) developed computer software to teach strategies for finding correct main ideas, and avoiding incorrect choices such as: (1) only expressing part of the main idea, (2) only expressing a specific detail, (3) too general, (4) unrelated. The results of post-test showed the accuracy of finding main ideas increased. Piquette (1994) pointed out that direct instruction of a self-questioning technique could promote the understanding of a main idea, and direct instruction through computer would increase learning motivation and maintenance of learning results. Sharp and Ashby (2002) implemented an action plan in special education classes of a middle school and a high school for thirteen weeks. The action plan included cooperative reading, SQ3R, self-questioning worksheets and reciprocal teaching. In the eighty-eight Passages Comprehension Series test, 24% students were unable to identify main ideas compared to 57% prior to the intervention. Sedita (1995) proposed a model that presented main idea, note taking, and summarizing skills which could be taught and practiced in grades four through high school for students with learning disabilities. Jitendra, Coleman, Hoppes and Wilson (1998) investigated the effects of a direct instruction main idea summarization program and a self-monitoring technique on the reading comprehension of four sixth-grade students with learning disabilities. The program produced increases in identifying and generating main ideas, with even higher 94

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

levels of performance following self-monitoring instruction. Furthering their research to older students, Jitendra, Hoppes and Xin (2000) trained middle school students with disabilities to identify and generate main idea statements using main idea strategy instruction and a self-monitoring procedure. Results showed that the experimental group outperformed the control group in reading comprehension on post-test and delayed post-test items. Kim, Vaughn, Wanzek and Wei (2004) made an extensive search of the professional literature between 1963 and 2001 and found that using graphic organizers was associated with improved reading comprehension overall for students with learning disabilities. Graphic organizers include semantic maps, framed outlines and Venn diagrams. Boulineau, Fore III, Hagen-burke and Burke (2004) used story-mapping to increase story-grammar text comprehension of students with learning disabilities. Using a descriptive, three-phased, single-subject design, the effect of story-map instruction on student participants comprehension of story-grammar elements was monitored. Positive results were observed and maintenance probes suggested the effects of the intervention were maintained. Bakken, Mastropieri and Scruggs (1997) found that text-structure-based reading strategies had a significant effect on recall of central and incidental information over traditional instruction on immediate, delayed and transfer tests on all measures. In the text-structure-based condition, students were taught to identify three types of passages (main idea, list and order). Findings indicated that eighth-grade students with learning disabilities could learn, apply and transfer complex text-structure-based strategies. Seidenberg (1989) reviewed research on text processing and made implications that the instruction of students with learning disabilities included strategy instruction and instruction in such text processing skills as identifying main idea and identifying text structure. Dickson (1995) indicated that reading comprehension was enhanced by text organization. Text organization includes the visual, physical organization such as heading and location of main idea. Since the main idea is an important part of text organization, this study embedded the main idea in the graphical organization to support students with hearing impairment in their reading.

3. METHOD

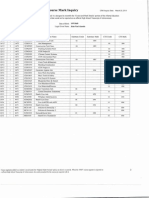

3.1 Participants The participants of this research were eight elementary students with hearing impairment. They were all mainstreamed in general-education classes at different elementary schools in Taichung City. They received general education without learning sign language and were supported by two itinerant special education teachers who participated in this study. Table 1 shows the participants demographic data:

95

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

3.2 Instrumentation The multimedia stories of Taiwanese deaf or hard-of-hearing celebrities included a famous model, a professor, a teacher, an athlete, a computer programmer, an illustrator, an insurance agent and a deaf leader. Their real stories were taken from the internet and edited by four special educators for the deaf or hard-of-hearing students. The multimedia software Flash was used to convert the text into multimedia form. The programmer was an English teacher for special education students, and the author was also a former English teacher. Figure 1 shows the story of a professor who is deaf. The English key words are colored with deep red indicating accented syllable and green or orange indicating other syllables. The syllabling is a mixture of English and Taiwanese Mandarin phonetic system, which may be easier for students with hearing impairment. The students in this study had learned Taiwanese Mandarin phonetic system, which was used alongside the Chinese traditional characters as shown in figure 1. When students click the mouse on the English key words to find their meanings, a pop-up window will show a video of a mouth pronouncing the word and a box with the words meaning in Chinese. Figure 2 shows the pop-up window.

Figure 3 is a graphic organizer of the story; it is intended to express the main idea and important details of the whole story. Table 1. Participants Demographic Data Participant Hearing loss Device Grade S1 Severe HA 5 S2 Severe CI 6 S3 Mild HA 3 S4 Mild HA 6 S5 Moderate HA 5 S6 Mild HA 2 S7 Mild HA 6 S8 Severe CI 2

Note. *HA = hearing aid; CI = cochlear implant.

Mode of communication Speech, writing, and gesture Speech, writing, and gesture Speech Speech Speech, writing, and gesture Speech Speech Speech

Figure 1. The text with English key words of the story of a professor who is deaf.

96

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

Figure 2. A pop-up window shows a video of pronouncing an English word and a box with its meaning in Chinese.

Figure 3. A graphic organizer of the story of a professor who is deaf.

3.3 Design and Procedure As the two itinerant special education teachers visited the eight hearing-impaired students separately for two hours a week, the students were taught a story for about an hour each week. Prior to teaching, the students were assessed in main idea identification, English word pronunciation, English word recognition, English word listening comprehension and English word lip-reading. Students were given the stories in Chinese on paper and asked to write the main ideas. Students were also given English words on paper to read aloud for the assessment of

97

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

pronunciation. Assessment of English word recognition, English word listening comprehension, and English word lip-reading was administered as multiple-choice items. During the computer assisted instruction students read from the screen and teachers encouraged them to guess and click on the English key words for their meanings and pronunciations. The teachers also explained unfamiliar Chinese words. The main ideas, the stories implications and important details were discussed with the help of the graphical organizers. After teaching, the students were assessed in main idea identification and English word pronunciation, recognition, listening comprehension, and lip-reading the same way as in the pre-test. The assessment, teaching and re-assessment lasted for eight weeks, as there were eight stories. After the last reassessment, a questionnaire was administered to the students to find their attitude toward the computer assisted instruction of multimedia stories of Taiwanese deaf or hard of hearing celebrities. Two weeks later, a follow-up assessment in English word pronunciation was administered to test the maintenance effect. Thus, the experiment lasted for ten weeks from beginning to end.

4. RESULTS

Table 2 shows that the post-test was significantly higher than the pre-test (***p < .001) in main idea identification. Students got two points if they wrote the main idea correctly for each story, and got one point if they wrote other important details instead of the main idea. Thus the full score was sixteen, as there were eight stories. Students improved from 4.55 to 14.625. Table 3 shows the means and standard deviations of the three pre-tests in English word recognition, English word listening comprehension, and English word lip-reading. Table 4 of the repeated measures ANOVA shows the difference was significant (*p < .05). The pre-test of English word lip-reading was significantly higher than those of English word listening comprehension and English word recognition (17.3750 > 13.7500 > 6.6250). It indicated lip-reading was helpful for hearing-impaired students in this study to learn English words.

Table 2. T test of the Difference between Pre and Post Tests of Main Ideas Tests M SD n t value df Pre 4.5000 2.92770 8 -9.555 7 Post 14.6250 2.06588 8

p .000

Table 3. Means and Standard Deviations of Three Pre-tests Pre-tests M English word recognition 6.6250 English word listening comprehension 13.7500 English word lip-reading 17.3750

SD 5.85388 9.31589 11.62433

n 8 8 8

98

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

Table 4. Repeated Measures ANOVA of Three Pre-tests Source SS df Ms F Pre-test 478.583 2 239.292 5.710 Error 586.750 14 41.911

Note. Mauchlys W= .500, Sphericity Assumed.

.670

P .015

Table 5. T test of the Difference between Pre and Post Tests of Word Recognition Tests M SD n t value df p Pre 6.6250 5.85388 8 -14.675 7 .000 Post 37.2500 3.19598 8

Table 6. T test of the Difference between Pre and Post Tests of Listening Comprehension Tests M SD n t value df p Pre 13.7500 9.31589 8 -5.965 7 .001 Post 31.6250 3.46152 8

Table 7. T test of the Difference between Pre and Post Tests of Lip-reading Tests M SD n t value df Pre 17.3750 11.62433 8 -4.669 7 Post 32.6250 4.10357 8

p .002

Table 5 shows the post-test was significantly higher than the pre-test (***p < .001) in English word recognition. There were five English key words for each story. Thus the full score was forty, as there were eight stories. Students improved from 6.6250 to 37.2500, almost the full score. Table 6 shows the post-test was significantly higher than the pre-test (**p < .01) in English word listening comprehension. Students improved from 13.7500 to 31.6250. The pre-test of English word listening comprehension was higher than that of English word recognition (13.7500 vs. 6.6250), while the post-test of English word listening comprehension was lower than that of English word recognition (31.6250 vs. 37.2500). The higher pre-test score in listening comprehension indicated that students with hearing impairment in the study had some phonologic awareness, but the lower post-test score in listening comprehension indicated that phonologic awareness could not be improved in as short a time as the word recognition. Table 7 shows the post-test was significantly higher than the pre-test (**p < .01) in English word lip-reading. Students improved from 17.3750 to 32.6250. Table 8 shows the post-test was significantly higher than the pre-test (***p < .001) in English word pronunciation. Students improved from 6.8813 to 64.6875. Two English teachers scored their pronunciation, and if students pronounced each syllable of a word correctly they would get 2 points. The full score was eighty, as there were forty English key words.

99

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

Table 8. T test of the Difference between Pre and Post Tests of Word Pronunciation Tests M SD n t value df p Pre 6.8813 8.67788 8 -12.206 7 .000 Post 64.6875 15.15144 8

Table 9. T test of the Difference between Post and Follow-up Tests of Word Pronunciation Tests M SD n t value df p Post 64.6875 15.15144 8 1.560 7 .163 Follow-up 52.9125 18.99071 8

Table 10. Students Attitude toward Multimedia Stories of Taiwanese Deaf Celebrities Items M SD 1. I like to read striving stories of people with hearing 3.5000 1.41421 impairment. 2. These stories make me believe I can succeed if I try hard. 4.1250 .64087 3. The graphical organization with main idea helps me 3.8750 .83452 understand the story. 4. I hope all stories provide graphical organization with main 4.1250 .83452 ideas. 5. These stories with English key words are helpful for 4.1250 .83452 learning English. 6. These stories with English key words are interesting for 3.6250 1.30247 learning English. 7. The graphical organization with English key words helps 3.5000 .92582 me remember the meanings of these words. 8. I hope teachers teach English words using graphical 3.7500 1.16496 organization with English key words. 9. Its easier to pronounce English words using colors to 4.0000 .92582 differentiate syllables. 10. I hope teachers teach English words using colors to 4.0000 .92582 differentiate syllables. 11. Its helpful to learn English words by lip-reading video of 3.6250 1.30247 a mouth articulating words. 12. I hope teachers teach English words using video for 3.6250 1.30247 lip-reading.

Two weeks after the post-test, a follow-up test was given to test the maintenance effect of the computer-assisted instruction. Their scores decreased from 64.6875 to 52.9125, but the difference was not significant statistically (p > .05) as shown in Table 9. In addition to the assessment of main idea identification and English word learning, a questionnaire was administered to the students to find their attitude toward the computer-assisted instruction of multimedia stories of Taiwanese deaf or hard of hearing celebrities. The questionnaire was a five point Likert scale, with a score of three as neutral. Table 10 shows that items receiving most positive scores were numbers: 2. (these stories make me believe I can succeed if I try hard), 4 (I 100

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

hope all stories provide graphical organization with main ideas) and 5 (these stories with English key words are helpful for learning English).

5. DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

1. Students felt these stories were encouraging and believed they would succeed by working hard as the characters in the stories did. Some students found these stories interesting, wanted to know more about them and searched in the internet for more information. These striving for success stories of the deaf or hard-of-hearing people provided valuable models for them to follow and motivated their desire to read. This may improve their reading, which is enriching and essential for students with hearing impairment. As they cannot hear very clearly, reading may be more important to them than hearing people. 2. Kelly et al. (2001) found that deaf college students in both the higher-level and lower-level reading groups did not identify the main idea of the passage from Science Watch. This study provided graphical organization with main ideas to help students with hearing-impairment, and the post-test was significantly higher than the pre-test in main idea identification. This scaffold of graphical organization seemed to work for students with hearing-impairment. Student also hoped all stories provide graphical organization with main ideas. This implied that teachers could use graphical organization in their teaching, or encourage students to develop graphic organization themselves. 3. The pre-test of English word lip-reading was significantly higher than those of English word listening comprehension and English word recognition (17.3750 > 13.7500 > 6.6250). It indicated lip-reading was helpful for hearing-impaired students in this study to learn English words. However, lip-reading is discouraged by the oral/auditory method which is the mainstream method for teaching students with hearing impairment in Taiwan. That might be the reason why some of the students disliked lip-reading. Since English is a foreign language and its pronunciation is very different from Mandarin Chinese, even some general education students have difficulty articulating English words correctly. Hearing impairment will pose particular difficulties for the deaf or hard-of-hearing students. Thus, lip-reading may be helpful for them to learn to speak English. 4. In this study, English words were colored with deep red indicating accented syllable and green or orange indicating other syllables. Students found its easier to pronounce English words using colors to differentiate syllables. The two teachers in charge of the experiment also found coloring syllables was helpful for themselves to articulate the English words clearly and to correct students pronunciation or provide models, as they were special education teachers and not very good in English themselves. Thus, using colors to differentiate syllables may also help many adults or students without hearing impairment to articulate English words. 5. It was observed by the teachers that students practiced and improved their English by repeatedly clicking on the English key words to hear the voice and

101

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

imitate the pronunciation. However, a few students with severe hearing loss were not able to catch up with the computer voice, which was recorded at a normal speed. After watching the teachers articulate the words at a slower speed, they got accustomed to the computer voice and could practice on the computer by themselves. Computers could not replace teachers, but could be effective and patient instructional assistants for teachers who want to improve and enrich their teaching through technology.

NOTE

This research was supported by a grant from the National Science Council of Taiwan. The grant number is NSC 95-2413-H-468-001.

REFERENCES

Andrews, J. F., & Jordan, D. L. (1998). Multimedia stories for deaf children. Teaching Exceptional Children, 30(5), 28-33. Bakken, J., Mastropieri, M., & Scruggs, T. (1997). Reading comprehension of expository science material and students with learning disabilities: A comparison of strategies. The Journal of Special Education, 31, 300-24. Barker, L. P. (2003). Computer-assisted vocabulary acquisition: The CSLU vocabulary tutor in oral-deaf education. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 8 (2), 187-198. Boulineau, T., Fore III, C., Hagen-burke, S., & Burke, M. D. (2004). Use of story-mapping to increase the story-grammar text comprehension of elementary students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 27, 105-121. Burke, J. (2003). The main idea organizer. Voices from the Middle, 10 (3), 52-53. Chang, B. L. (1987). A study of the language ability of main-streamed students with hearing impairment. Journal of Special Education Research, 3, 119-134. [in Chinese] Chang, B. L. (1989). A study of the language ability of students with hearing impairment. Journal of Special Education Research, 5, 165-204. [in Chinese] Chi, B. S. (2000). An analysis of reading comprehension of students with hearing impairment. Journal of Taiwan Education College, 14, 155-187. [in Chinese] Chou, L. D. (2006, December). The report of a survey result by the department of human development and family of National Taiwan Normal University [in Chinese]. Paper presented at the conference of alliance of teacher education institutions, Taipei, Taiwan. Copra, E. R. (1990). Using interactive videodiscs for bilingual education. Perspectives in Education and Deafness, 8(5), 9-11.

102

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

Dickson, S. (1995). Text organization and its relation to reading comprehension: A synthesis of the research. Technical Report No. 17. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 386 864) Flaherty, M., & Moran, Ai. (2004). Deaf signers who know Japanese remember words and numbers more effectively than deaf signers who know English. American Annals of the Deaf, 147(1), 39-45. Fogel, N. S. (1990, April). A computer approach to teaching English syntax to deaf students. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Boston, MA, USA. Gallaudet Research Institute (1996). Standard achievement test 9th edition: Norms booklet for deaf and hard-ofhearing students. Washington, DC, USA: Gallaudet University. Gentry, M., Chinn, K., & Moulton, R. (2005). Effectiveness of multimedia reading materials when used with children who are deaf. American Annals of the Deaf, 149(5), 394-403. Gillespie, C. W., & Twardosz, S. (1997). A group story-reading intervention with children at a residential school for the deaf. American Annals of the Deaf, 142, 320-332. Hanson, V. L., & Padden, C. A. (1989). Interactive video for bilingual ASL/English instruction of deaf children. American Annals of the Deaf, 134(3), 209-213. Higgins, K., Boone, R., & Lovitt, T. C. (1996). Hypertext support for remedial students an students with disabilities. Journal of Leaning Disabilities, 29(4), 402-412. Hillinger, M. L. (1994, June). Using hypermedia to support understanding of expository text: Examples from the workplace and classroom. Paper presented at the Annual National Educational Computing Conference, Boston, MA, USA. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No ED 396 668). Jitendra, A. K., Coleman, C. L., Hoppes, M. K., & Wilson, B. (1998). Effects of a direct instruction main idea summarization program and self-monitoring on reading comprehension of middle school students with learning disabilities. Reading and Writing Quarterly: Overcoming Learning Difficulties, 4(4), 379-396. Jitendra, A., Hoppes, M., & Xin, Y. (2000). Enhancing main idea comprehension for students with learning problems: The role of a summarization strategy and self-monitoring instruction. Journal of Special Education, 34(3), 127-39. Kelly, L. P. (2003). Consideration for designing practice for deaf readers. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 8(2), 171-186. Kelly, R., Albertini, J., & Shannon, N. (2001). Deaf college students reading comprehension and strategy use. American Annals of the Deaf, 146(5), 385-400. Kim, A., Vaughn, S., Wanzek, J., & Wei, S. (2004). Graphic organizers and their effects on the reading comprehension of students with LD. Journal of Learning Disabilites, 37(2), 105-118. Lin, B. G., & Lee, J. S. (1987). A study of language ability of students with hearing impairment. Journal of Taiwan Education College, 12, 1-27. [in Chinese]

103

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

Lindstrand, P. (2001). Parents of children with disabilities evaluate the importance of the computer in child development. Journal of Special Education Technology, 16(2), 43-52. Luetke-Stalman, B., & Nielson, D. C. (2003). The contribution of phonologic awareness and receptive and expressive English to the reading ability of deaf students with varying degrees of exposure to accurate English. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 8(4), 464-484. Mayer, M. J., & Lee, Y. B. (1995). Closed-captioned prompt rates: Their influence on reading outcomes. Paper presented at the annual national conventional of the association for educational communications and technology, 17th, Anaheim, CA, USA. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No ED 383 226). Piquette, M. (1994). A multi-modal approach to remediating main-idea comprehension efficiencies in behavior-disorder students. Master of science practicum report, Nova University, USA. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No ED 379 828) Prinz, P. M., Nelson, K. E., Geysels, G., & Willems, C. (1993). A multimodality and multimedia approach to language, discourse, and literacy development. In Ben A. Elsendoorm & Frans Conix (Eds.), Interactive learning technology for the deaf. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. Sedita, J. (1995). A call for more study skills instruction. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 380 973) Seidenberg, P. L. (1989). Relating text-processing research to reading and writing instruction for learning disabled students. Learning Disabilities Focus, 5(1), 4-12. Sharp, P., & Ashby, D. (2002). Improving students comprehension skills through instructional strategies. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED468240). Stevens, R. J. (1986). The effects of strategy training on the identification of main ideas of expository passages, report no.4. Center for Research on Elementary and Middle Schools, Baltimore, MD, USA. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No ED 297 265). Tsai, S. F. (1994). A study of learning strategies and related factors of middle school students with hearing impairment. [in Chinese] Unpublished Masters thesis of the Graduate Institute of Special Education of National Chang-Hua University, Taiwan. van den Broek, P., Lynch, J., Naslund, J., Ievers-Landis, C., & Verduin, K. (2003) The development of comprehension of main ideas in narratives: Evidence from the selection of titles. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(4), 707-18. Volterra, V. (1995). Advanced learning technology for a bilingual education of deaf children. American Annals of Deaf, 140(5), 402-409. Xin, F., Glaser, W. G., & Rieth, H (1996). Multimedia reading using anchored instruction an video technology in vocabulary lessons. Teaching Exceptional Children, 28(6), 45-49.

104

J. M. Ju / Asian Journal of Management and Humanity Sciences, Vol. 4, No. 2-3, pp. 91-105, 2009

Jing-Ming Ju received the Doctoral degree in education from the University of Northern Colorado in 1983, and the M. S. degree in special education technology from the Johns Hopkins University. Dr. Ju was a professor and Department chair at National Taichung University for many years. His current research interests include learning disabilities, hearing impairment, and assistive technology.

105

Вам также может понравиться

- Invisible CitiesДокумент14 страницInvisible Citiesvelveteeny0% (1)

- Articulatory+Phonetic+Drills +Tools+in+Enhancing+the+Pronunciation+among+High+School+StudentsДокумент20 страницArticulatory+Phonetic+Drills +Tools+in+Enhancing+the+Pronunciation+among+High+School+Studentsarjhel saysonОценок пока нет

- Caterpillar Cat C7 Marine Engine Parts Catalogue ManualДокумент21 страницаCaterpillar Cat C7 Marine Engine Parts Catalogue ManualkfsmmeОценок пока нет

- Praise and Worship Songs Volume 2 PDFДокумент92 страницыPraise and Worship Songs Volume 2 PDFDaniel AnayaОценок пока нет

- Detail Design Drawings: OCTOBER., 2017 Date Span Carriage WayДокумент26 страницDetail Design Drawings: OCTOBER., 2017 Date Span Carriage WayManvendra NigamОценок пока нет

- Phonological and Phonemic AwarenessДокумент11 страницPhonological and Phonemic AwarenessMay Anne AlmarioОценок пока нет

- Reading Interventions for the Improvement of the Reading Performances of Bilingual and Bi-Dialectal ChildrenОт EverandReading Interventions for the Improvement of the Reading Performances of Bilingual and Bi-Dialectal ChildrenОценок пока нет

- Down Syndrome 2Документ19 страницDown Syndrome 2Renelli Anne GonzagaОценок пока нет

- Toe by ToeДокумент17 страницToe by Toe1230% (2)

- CG Photo Editing2Документ3 страницыCG Photo Editing2Mylene55% (11)

- Healthy Apps Us New VarДокумент9 страницHealthy Apps Us New VarJESUS DELGADOОценок пока нет

- Early Reading For Young Deaf Alt FrameworkДокумент13 страницEarly Reading For Young Deaf Alt Frameworkapi-316697752Оценок пока нет

- View All Callouts: Function Isolation ToolsДокумент29 страницView All Callouts: Function Isolation Toolsمهدي شقرونОценок пока нет

- Chapters 1, 2, 3rДокумент45 страницChapters 1, 2, 3rLenAlcantaraОценок пока нет

- Videos EducactivosДокумент6 страницVideos EducactivosLuis A. Cardoza CastroОценок пока нет

- Research Proposal: ProjectДокумент7 страницResearch Proposal: ProjectrabiaОценок пока нет

- Ok 08Документ10 страницOk 08yd pОценок пока нет

- Using Technology To Help ESLДокумент6 страницUsing Technology To Help ESLActivities CoordinatorОценок пока нет

- Comprehension Strategies: Effect On Reading Comprehension of Children With Hearing ImpairmentДокумент11 страницComprehension Strategies: Effect On Reading Comprehension of Children With Hearing ImpairmentFakerPlaymaker100% (1)

- Which Is The Most Appropriate Strategy For Very Young Language Learners?Документ9 страницWhich Is The Most Appropriate Strategy For Very Young Language Learners?Nita IrfayaniОценок пока нет

- Computer Use in Language LearningДокумент6 страницComputer Use in Language LearningImran MaqsoodОценок пока нет

- Digital Stories To Improve Listening Skills in Spanish ChildrenДокумент15 страницDigital Stories To Improve Listening Skills in Spanish ChildrenLeo AngieОценок пока нет

- Building A Powerful Reading ProgramДокумент17 страницBuilding A Powerful Reading ProgramInga Budadoy NaudadongОценок пока нет

- 1 SM PDFДокумент13 страниц1 SM PDFRika AprianiОценок пока нет

- Artikel Jurnal 1, 2, 3Документ17 страницArtikel Jurnal 1, 2, 3NORFADZLIANA ROHANIОценок пока нет

- Essential Need Orton Gillingham 2Документ25 страницEssential Need Orton Gillingham 2taticastilloОценок пока нет

- Chen L1toL2reading20221215Документ40 страницChen L1toL2reading20221215courursulaОценок пока нет

- Coppens2011 Article DepthOfReadingVocabularyInHearДокумент15 страницCoppens2011 Article DepthOfReadingVocabularyInHearMariaP12Оценок пока нет

- Critique 1Документ3 страницыCritique 1emyeuaiОценок пока нет

- Jls 026 s3 036 Valipour Differences LearningДокумент4 страницыJls 026 s3 036 Valipour Differences LearningSobat NugasОценок пока нет

- Factors Contributing To Parents Selection ofДокумент10 страницFactors Contributing To Parents Selection ofBayazid AhamedОценок пока нет

- Storytelling As A Reading Comprehension Instructional Strategy Fisseha-Derso-READYДокумент11 страницStorytelling As A Reading Comprehension Instructional Strategy Fisseha-Derso-READYTadesse BitewОценок пока нет

- Using Puppets For Language TeachingДокумент14 страницUsing Puppets For Language Teachingt-poh91Оценок пока нет

- The Impact of A Dialogic Reading Program On Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Kindergarten and Early Primary School-Aged Students in Hong KongДокумент14 страницThe Impact of A Dialogic Reading Program On Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Kindergarten and Early Primary School-Aged Students in Hong Kongp.ioannidiОценок пока нет

- 03 PDFДокумент9 страниц03 PDFTati MuflihahОценок пока нет

- Annotated BibliographyДокумент5 страницAnnotated BibliographyLIWANAGAN MARYJOICEОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Movie Subtitles On EFL LearnersOral PerformanceДокумент15 страницThe Effect of Movie Subtitles On EFL LearnersOral PerformanceUtari DamayantiОценок пока нет

- Article 281 PDFДокумент25 страницArticle 281 PDFRiska Nahara SyahputriОценок пока нет

- Research Proposal: ProjectДокумент9 страницResearch Proposal: ProjectrabiaОценок пока нет

- A Conjoint Analysis of The Listening Activity Preferences of A Select Group of Grade 7 and Grade 8 Students From Philippine Provincial SchoolДокумент20 страницA Conjoint Analysis of The Listening Activity Preferences of A Select Group of Grade 7 and Grade 8 Students From Philippine Provincial SchoolReinalene Macolor GonzagaОценок пока нет

- 2028 5411 1 PBДокумент14 страниц2028 5411 1 PBThang Nguyen ChienОценок пока нет

- 6775 8884 1 PB PDFДокумент6 страниц6775 8884 1 PB PDFMathematicaRoomОценок пока нет

- Insights Into Listening Comprehension Problems: A Case Study in VietnamДокумент24 страницыInsights Into Listening Comprehension Problems: A Case Study in VietnamAn AnОценок пока нет

- Switzerland TOKUHAMA Ten Key Factors 2Документ230 страницSwitzerland TOKUHAMA Ten Key Factors 2sammlissОценок пока нет

- ListeningДокумент9 страницListeningkskskОценок пока нет

- Hirsh-Pasek and Golinkoff 2012Документ49 страницHirsh-Pasek and Golinkoff 2012Francisco Javier Echenique ArosОценок пока нет

- Longitudinal Associations of Phonological Processing Skills, Chinese Word Reading, and ArithmeticДокумент21 страницаLongitudinal Associations of Phonological Processing Skills, Chinese Word Reading, and ArithmeticLuana TeixeiraОценок пока нет

- Dfe 00155 2011B PDFДокумент7 страницDfe 00155 2011B PDFoanadraganОценок пока нет

- Reading Comprehension - A Computerized Intervention With Primary-Age Poor ReadersДокумент22 страницыReading Comprehension - A Computerized Intervention With Primary-Age Poor ReadersPaulo DaudtОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Films With and Without Subtitles On Listening Comprehension of EFL LearnersДокумент13 страницThe Effect of Films With and Without Subtitles On Listening Comprehension of EFL LearnersIsabel BlackОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Watching Authentic Videos On Improvement of Listening Comprehension Ability PDFДокумент9 страницThe Effect of Watching Authentic Videos On Improvement of Listening Comprehension Ability PDFTHEA URSULA EMANUELLE RACUYAОценок пока нет

- Podcast Effects On EFL Learners Listening ComprehensionДокумент10 страницPodcast Effects On EFL Learners Listening ComprehensionSyafira Rahmi AzkiaОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1 RHODAДокумент55 страницChapter 1 RHODAJosenia ConstantinoОценок пока нет

- Reading in A Foreign LanguageДокумент22 страницыReading in A Foreign LanguageDaniLu MBОценок пока нет

- John Howrey - Improving Listening Skills Through Studentgenerated Listening ActivitiesДокумент17 страницJohn Howrey - Improving Listening Skills Through Studentgenerated Listening ActivitiesSamet Erişkin (samterk)Оценок пока нет

- PaperC 1342Документ19 страницPaperC 1342Lenny ArfianiОценок пока нет

- Child Psychology Psychiatry - 2008 - Bowyer Crane - Improving Early Language and Literacy Skills Differential Effects ofДокумент11 страницChild Psychology Psychiatry - 2008 - Bowyer Crane - Improving Early Language and Literacy Skills Differential Effects ofKhoa Lê AnhОценок пока нет

- Vocab PreKДокумент13 страницVocab PreKKhaerel Jumahir PutraОценок пока нет

- The Effect of Using Vocabulary Flash Card On Iranian Pre-UniversityДокумент14 страницThe Effect of Using Vocabulary Flash Card On Iranian Pre-UniversitySiti Zaleha HamzahОценок пока нет

- Right of Knowing and Using Mother Tongue: A Mixed Method StudyДокумент9 страницRight of Knowing and Using Mother Tongue: A Mixed Method StudyDenniseElarcosaОценок пока нет

- The Correlation Between Listening and Speaking Among High School StudentsДокумент13 страницThe Correlation Between Listening and Speaking Among High School Studentsالهام شیواОценок пока нет

- The Effects of Extensive Reading Via E-Books On Tertiary Level Efl Students' Reading Attitude, Reading Comprehension and VocabularyДокумент10 страницThe Effects of Extensive Reading Via E-Books On Tertiary Level Efl Students' Reading Attitude, Reading Comprehension and VocabularyAngelu EmОценок пока нет

- Media Exposure and S Tudents' Communicative English As Second Language (Esl) PerformanceДокумент11 страницMedia Exposure and S Tudents' Communicative English As Second Language (Esl) PerformanceMatthewОценок пока нет

- Chapter 1Документ22 страницыChapter 1Bhin BhinОценок пока нет

- RRLДокумент3 страницыRRLJiro LatОценок пока нет

- Analysis of Barriers in Listening CompreДокумент7 страницAnalysis of Barriers in Listening CompreRANDAN SADIQОценок пока нет

- The Effects of Film Subtitles On English ListeningДокумент8 страницThe Effects of Film Subtitles On English ListeningRahma WulanОценок пока нет

- Industrial ExperienceДокумент30 страницIndustrial ExperienceThe GridLockОценок пока нет

- Design of Reinforced Cement Concrete ElementsДокумент14 страницDesign of Reinforced Cement Concrete ElementsSudeesh M SОценок пока нет

- FHWA Guidance For Load Rating Evaluation of Gusset Plates in Truss BridgesДокумент6 страницFHWA Guidance For Load Rating Evaluation of Gusset Plates in Truss BridgesPatrick Saint-LouisОценок пока нет

- Engleza Referat-Pantilimonescu IonutДокумент13 страницEngleza Referat-Pantilimonescu IonutAilenei RazvanОценок пока нет

- Teaching Trigonometry Using Empirical Modelling: 2.1 Visual Over Verbal LearningДокумент5 страницTeaching Trigonometry Using Empirical Modelling: 2.1 Visual Over Verbal LearningJeffrey Cariaga Reclamado IIОценок пока нет

- Literature Review Template DownloadДокумент4 страницыLiterature Review Template Downloadaflsigfek100% (1)

- 19 Dark PPT TemplateДокумент15 страниц19 Dark PPT TemplateKurt W. DelleraОценок пока нет

- Jul - Dec 09Документ8 страницJul - Dec 09dmaizulОценок пока нет

- Victor 2Документ30 страницVictor 2EmmanuelОценок пока нет

- Hockney-Falco Thesis: 1 Setup of The 2001 PublicationДокумент6 страницHockney-Falco Thesis: 1 Setup of The 2001 PublicationKurayami ReijiОценок пока нет

- The Turning Circle of VehiclesДокумент2 страницыThe Turning Circle of Vehiclesanon_170098985Оценок пока нет

- Universitas Tidar: Fakultas Keguruan Dan Ilmu PendidikanДокумент7 страницUniversitas Tidar: Fakultas Keguruan Dan Ilmu PendidikanTheresia Calcutaa WilОценок пока нет

- SPC FD 00 G00 Part 03 of 12 Division 06 07Документ236 страницSPC FD 00 G00 Part 03 of 12 Division 06 07marco.w.orascomОценок пока нет

- SP-Chapter 14 PresentationДокумент83 страницыSP-Chapter 14 PresentationLoiDa FloresОценок пока нет

- China Training WCDMA 06-06Документ128 страницChina Training WCDMA 06-06ryanz2009Оценок пока нет

- Module 5 What Is Matter PDFДокумент28 страницModule 5 What Is Matter PDFFLORA MAY VILLANUEVAОценок пока нет

- PM Jobs Comp Ir RandДокумент9 страницPM Jobs Comp Ir Randandri putrantoОценок пока нет

- Research FinalДокумент55 страницResearch Finalkieferdem071908Оценок пока нет

- De Thi Hoc Ki 1 Lop 11 Mon Tieng Anh Co File Nghe Nam 2020Документ11 страницDe Thi Hoc Ki 1 Lop 11 Mon Tieng Anh Co File Nghe Nam 2020HiềnОценок пока нет

- Department of Education: Template No. 1 Teacher'S Report On The Results of The Regional Mid-Year AssessmentДокумент3 страницыDepartment of Education: Template No. 1 Teacher'S Report On The Results of The Regional Mid-Year Assessmentkathrine cadalsoОценок пока нет

- PD3 - Strategic Supply Chain Management: Exam Exemplar QuestionsДокумент20 страницPD3 - Strategic Supply Chain Management: Exam Exemplar QuestionsHazel Jael HernandezОценок пока нет

- Img 20150510 0001Документ2 страницыImg 20150510 0001api-284663984Оценок пока нет

- Generation III Sonic Feeder Control System Manual 20576Документ32 страницыGeneration III Sonic Feeder Control System Manual 20576julianmataОценок пока нет