Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Man Shot by Police Loses Appeal

Загружено:

Edmonton SunАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

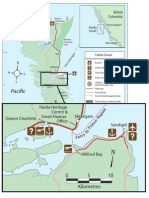

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Man Shot by Police Loses Appeal

Загружено:

Edmonton SunАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

In the Court of Appeal of Alberta

Citation: R v Davis, 2013 ABCA 15 Date: 20130124 Docket: 1103-0114-A Registry: Edmonton

Between: Her Majesty the Queen Respondent - and Percy Walter Davis Appellant

_______________________________________________________ The Court: The Honourable Chief Justice Catherine Fraser The Honourable Mr. Justice Clifton OBrien The Honourable Mr. Justice J.D. Bruce McDonald _______________________________________________________

Memorandum of Judgment of The Honourable Mr. Justice OBrien and The Honourable Mr. Justice McDonald Dissenting Memorandum of Judgment of The Honourable Chief Justice Fraser

Appeal from the Conviction by The Honourable Madam Justice M.G. Crighton Dated the 11th day of April, 2011 (Docket: 081329385Q1)

_______________________________________________________ Memorandum of Judgment _______________________________________________________ The Majority: I. Introduction [1] The appellant, Percy Walter Davis, was shot in the chest and neck during a confrontation with a police officer outside an Edmonton shopping mall. Davis was later charged and convicted of possession of a weapon (a knife) for a dangerous purpose, assault of a police officer in the execution of duty, and assault of the same officer with a weapon. He appeals these convictions and seeks a new trial. He submits the trial judge erred by giving insufficient reasons and by failing to find that his Charter rights were breached by the use of excessive force in effecting his arrest. For the reasons that follow, we dismiss the appeal. II. Background [2] The trial extended over several days and more than 20 witnesses were called. Some of the facts were contested at trial. Relying primarily on the evidence of Cst. Myles Stromner, the officer who shot the appellant, the trial judge found as follows. [3] On August 8, 2008 the Edmonton Police Service received a report that a person armed with a butcher knife was riding a bicycle around the parking lot of the Abbotsfield Mall in Edmonton. Cst. Stromner was dispatched to investigate. [4] Stromner attended the mall and drove around the parking lot looking for the individual with the knife. Along the way he spoke to two people, Barry Andrews and Jill Thomas, asking if they had seen the person he was looking for. Both later gave evidence at the trial. [5] As he was about to give up the search, Stromner saw a young man riding a bike who matched the description Stromner had been given. This was the appellant. Stromner followed behind him in his police car as Davis headed down 119th Avenue NW on his bicycle. [6] Near the end of the street, Stromner sounded his air horn twice and activated the police cars emergency lights, but before he could get out of the car Davis charged the police car with a knife in his hand. [7] The drivers side window of the police car was open. Seeing the knife, and believing he might be stabbed, Stromner covered his head and leaned towards the passenger side of the vehicle. As a consequence he did not see what Davis did with the knife. When the stabbing did not occur, Stromner un-holstered his revolver, unbuckled his seatbelt, and attempted to get out the drivers side door. He met brief resistence, as Davis pushed back, but Davis quickly relented and Stromner was able to open the door and get out. As he did so, he observed Davis forward of the door holding a knife over his head. In finding the attack occurred, as alleged by Stromner, the trial judge noted that Stromners evidence was confirmed by an eyewitness.

Page: 2

[8] Once out of the police car, Stromner told Davis to back up and drop the knife. Stromner then gave a 10-13 emergency signal over the radio, an indication that an officer is in distress and needs help immediately. [9] Davis picked up his bike and walked away. Stromner, with revolver drawn, followed Davis and shouted at him many times to drop the knife. Davis continued to walk away. At some point Davis turned to face Stromner and Stromner pepper sprayed him in the face. Stromner perceived the pepper spray to have no effect. The trial judge noted that other witnesses made the same observation. [10] Davis continued to walk away, with Stromner following, revolver pointing at eye level, demanding that Davis drop the knife. At this point, Stromner updated his status over the police radio by downgrading the alert to a 10-17, an indication that an officer needs help but not as immediately as with a 10-13 alert. He continued to follow Davis, from a short distance, repeating the command that he drop the knife. [11] Davis was proceeding down the east side of Abbotsfield Road NW when he decided to cross the road near the McDonalds parking lot located on the west side of the street. McDonalds is in the southeast corner of the Abbotsfield Mall. Stromner advised police dispatch that he needed a taser as Davis was moving in the direction of the Mall where Stromner had earlier observed that people were present. Stromner followed Davis over the median to the parking area at the back of McDonalds. [12] Stromner was concerned by this point that they would soon reach a populated area, where his options in stopping Davis would be limited. Stromner had already determined that he would not let Davis get near people while still in possession of the knife. When it became apparent that Davis was not willing to drop the knife, Stromner decided to shoot. Davis turned to face him and raised the knife in the air. At this point, Stromner shot Davis twice in quick succession, once to the right of the appellants Adams apple, and once in the right chest. [13] Two other police officers arrived at the moment of the shooting Cst. Griffith in a police cruiser and Cst. Leblanc on foot. Davis remained standing. Leblanc gave a verbal direction to Davis to get down. After a few moments, Davis dropped the knife and toppled over onto his back. [14] Davis was taken to hospital for treatment. His injuries were life-threatening. He was later charged with the offences described above. The Alberta Serious Incident Response Team (ASIRT) conducted an investigation into the incident and exonerated Stromner. III. The Trial Decision [15] The trial judge made an initial assessment of the credibility of two witnesses a civilian witness, Mike Abdullah, and Stromner. Abdullahs evidence set him apart from the other civilian witnesses because he had testified, among other things, that a second police officer, Cst. Griffith, was at the scene at the time of the shooting. Davis did not testify at the trial.

Page: 3

[16] The trial judge found Abdullah was a witness hostile to both the defence and the Crown, and that his evidence was not objective. She concluded that his suggestion that Cst. Griffith had appeared prior to the shooting was contradicted by the evidence of all the other witnesses. As for Stromner, the trial judge found him forthright, fair, and a credible witness, and she accepted his version of events concerning his confrontation with the appellant, noting that in various instances it was confirmed by other witnesses. [17] After reciting the facts, the trial judge turned to the three charges. She looked first at the charge under section 88(1) of the Criminal Code of possessing a knife for a purpose dangerous to the public peace. She rejected the idea that the knife was being used in self-defence to thwart an unlawful detention, and found that Davis actions in charging the police car with the knife in hand, refusing to drop the knife after repeated requests, and waving the knife around, occasionally making forward thrusting motions, indicated an intention to use the knife for a dangerous purpose. Although some witnesses testified that Davis was acting strangely, and there was some suggestion that he was cognitively impaired, no expert evidence was called so as to displace the usual presumption that he intended the reasonable and probable consequences of his acts. She found Davis had committed the offence charged in count 1. [18] She turned to the charge of assaulting a police officer engaged in the execution of duty under section 270(1)(a). She found that in charging the police cruiser with a butcher knife in his hand, at a time when the officer inside was actively searching for a man with a knife in response to an expressed public concern, Davis had committed an assault against a police officer while he was engaged in the execution of duty. She found it did not matter that Stromner did not believe that a crime had been committed at the time. It was sufficient that he was lawfully making a general inquiry to determine if Davis possession of the knife constituted a threat to the public. Thus, she found the appellant had committed the offence charged in count 2. [19] The remaining charge was committing an assault against a police officer while using, or threatening to use, a weapon in this case, a knife contrary to section 267(b) of the Code. The trial judge observed that she had already found the appellant had committed the assault, with the result that the only remaining question was whether he used the knife to effect this purpose. She concluded: I agree with the Crown that Mr. Davis, in committing the assault threatened Constable Stromner first by charging the police cruiser with a knife in his hand, and thereafter, by presenting it above his head and waving it around as Constable Stromner tried to lawfully disarm him. I agree with the Crown that Mr. Davis brandishing of his knife was an implied threat, as there was no other evidentiary purpose for displaying the knife in the manner that he did. [ARD 000009] [20] Thus, she found that the third charge had been made out.

Page: 4

[21] At this point, the trial judge turned to defence allegations that Davis rights under sections 7, 9, 10(a), 11(d) and 12 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms had been abrogated. The parties had agreed that these issues could be dealt with in the course of the trial rather than through a voir dire. She found that the appellants immediate attack upon the police car made it impossible for Stromner to make any inquiries about whether Davis possessed a knife, or to decide whether the knife posed a threat to public peace. Thus, there was no arbitrary detention contrary to section 9. Furthermore, she found that while there might have been a reason for the appellant to feel as if he was under some form of arrest, while he was being pursued at gunpoint, the opportunity to communicate the reasons for detention or arrest did not present itself until Mr. Davis lay injured on the ground. Thus, there was no breach of section 10(a). [22] The remaining alleged Charter breaches related to the allegations that the police has used excessive force, or they had conducted a negligent investigation into the police involved shooting. The suggestion that the police had used excessive force engaged section 25of the Code, the relevant portions of which read: 25(1) Every one who is required or authorized by law to do anything in the administration or enforcement of the law ... (b) as a peace officer of public officer... ... is, if he acts on reasonable grounds, justified in doing what he is required or authorized to do and in using as much force as is necessary for that purpose. ... (3) Subject to subsections (4) and (5), a person is not justified for the purposes of subsection (1) in using force that is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm unless the person believes on reasonable grounds that it is necessary for the self-preservation of the person or the preservation of anyone under that persons protection from death or bodily harm. (4) A peace officer, and every person lawfully assisting the peace officer, is justified in using force that is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm to a person to be arrested, if

Page: 5

(a) the peace officer is proceeding lawfully to arrest, with or without warrant, the person to be arrested; (b) the offence for which the person is to be arrested is one for which that person may be arrested without warrant; (c) the person to be arrested takes flight to avoid arrest; (d) the peace officer or other person using the force believes on reasonable grounds that the force is necessary for the purpose of protecting the peace officer, the person lawfully assisting the peace officer or any other person from imminent or future death or grievous bodily harm; and (e) the flight cannot be prevented by reasonable means in a less violent manner. [23] The defence submitted that, once it had demonstrated that force had been used, the Crown bore the onus to of proving the factors justifying the use of force, under the applicable subsections of section 25, beyond a reasonable doubt. The trial judge disagreed, finding that although the Crown was required to prove the charges beyond a reasonable doubt, the onus was on Davis to demonstrate that his Charter rights had been breached. Thus, she held that Davis bore the burden of establishing that the requirements of section 25 had not been met on a balance of probabilities. [24] She then reviewed the evidence and found that Stromner had used what efforts he could to obtain help, that he had not heard the sirens of approaching police, and that at the point of the shooting he had no other choice but to shoot in order to stop Davis from entering an area with people in it. She also found Stromner did not recognize Davis, despite having encountered him before, and she rejected the defence suggestion that in shooting Davis the police officer acted out of malice or anger. As well, the trial judge found that in these particular circumstances Stromner was not obliged to issue a warning that he would shoot before actual shooting, as any reasonable person in the appellants position would have understood the consequences of failing to comply with a request to drop a knife given by a police officer pointing a revolver at him, especially after the pepper spray had not worked. [25] The trial judge concluded, on the evidence before her, that on a balance of probabilities Stromner was justified in acting as he did. She concluded, therefore, that Davis Charter rights had not been breached through the use of excessive force.

Page: 6

[26] Finally, she examined the police investigation into the shooting conducted by ASIRT. She concluded: In my view, the ASIRT investigation did not fall below the overarching standard of the reasonable police officer in the circumstances. There were many resources that could have been deployed, but the lead investigators reasons for not doing so were sound given the available evidence. Perhaps more important, there was no evidence about how the failure to take those steps in any way prejudiced the accuseds ability to make full answer and defence or in any way undermined the integrity of the judicial system. The investigation did not breach Mr. Davis s. 7 and s. 11(d) rights. [27] In the end, therefore, the trial judge concluded there was no need to grant a Charter remedy by excluding evidence or granting a stay. She convicted Davis on all three counts, although she entered a stay on Count 1 because it arose out of the same facts as Count 3. She also noted, in dicta, that she could take account of the fact that Davis had been shot and injured as part of sentencing. This appears to have happened, as Davis was later given a suspended sentence. IV. Grounds of Appeal [28] Davis originally advanced three grounds of appeal. At the appeal hearing, however, one of those grounds was abandoned. The remaining grounds of appeal are: (a) the learned trial judge erred in failing to give sufficient reasons; and (b) the learned trial judge erred in her analysis of whether or not the appellants Charter rights were breached. V. Analysis A. Ground One The alleged failure to give reasons [29] Davis submits the trial judge erred by giving insufficient reasons on the issue of credibility, with the result that this Court cannot determine how she arrived at her findings of fact. More specifically, the appellant points to Stromners evidence about the alleged assault at the police car and notes that his evidence that the police car was charged by the knife-wielding Davis was contradicted by three civilian witnesses Susan Giffen, Jill Thomas and Mathew Debeurs who testified that Stromner simply got out of the police car unimpeded and approached Davis demanding that he drop the knife. He submits the trial judge was obliged to explain her reasons for rejecting this evidence, as the allegation that Davis had committed some form of assault at the police car was central to the trial judges findings on all three charges. Davis makes a similar argument in relation to Stromners testimony about the appellants handling of the knife evidence, he submits, was also

Page: 7

contradicted by the evidence of several civilian witnesses who testified that they did not see Davis raise the knife above his head, or that they did not see the knife at all. [30] The starting point with respect to this ground of appeal is the general rule regarding the sufficiency of reasons set out by the Supreme Court in R v Sheppard, 2002 SCC 26, [2002] 1 SCR 869. Binnie J stated at para 28: The simple underlying rule is that if, in the opinion of the appeal court, the deficiencies in the reasons prevent meaningful review of the correctness of the decision, then an error of law has been committed. [31] The Supreme Court has elaborated upon this simple underlying rule in a number of more recent cases and, in particular, has discussed the sufficiency of reasons in the context of findings of credibility. In R v Dinardo, 2008 SCC 24, [2008] 1 SCR 788. Charron J noted, at paras 26-27: At the trial level, reasons justify and explain the result (Sheppard, at para. 24). Where a case turns largely on determinations of credibility, the sufficiency of the reasons should be considered in light of the deference afforded to trial judges on credibility findings. Rarely will the deficiencies in the trial judges credibility analysis, as expressed in the reasons for judgment, merit intervention on appeal. Nevertheless, a failure to sufficiently articulate how credibility concerns were resolved may constitute reversible error (see R. v. Braich, [2002] 1 S.C.R. 903, 2002 SCC 27 at para. 23). As this Court noted in R. v. Gagnon, [2006] 1 S.C.R. 621, 2006 SCC 17, the accused is entitled to know why the judge is left in reasonable doubt: Assessing credibility is not a science. It is very difficult for a trial judge to articulate with precision the complex intermingling of impressions that emerge after watching and listening to witnesses and attempting to reconcile the various versions of events. That is why this court decided, most recently in H.L., that in the absence of a palpable and overriding error by the trial judge, his or her perceptions should be respected. This does not mean that a court of appeal can abdicate its responsibility for reviewing the record to see whether the findings of fact are reasonably available. Moreover, where the charge is a serious one and

Page: 8

where, as here, the evidence of a child contradicts the denial of an adult, an accused is entitled to know why the trial judge is left with no reasonable doubt. [paras. 20-21] Reasons acquire particular importance where the trial judge must resolve confused and contradictory evidence on a key issue, unless the basis of the trial judges conclusion is apparent from the record (Sheppard, at para. 55). [32] These comments were adopted and expanded upon by McLachlin CJC in R v REM, 2008 SCC 51, [2008] 3 SCR 3. The Chief Justice stated, at paras 50-51: What constitutes sufficient reasons in issues of credibility may be deduced from Dinardo, where Charron J. held that findings on credibility must be made with regard to the other evidence in the case (para 23). this may require at least some reference to the contradictory evidence. However, as Dinardo makes clear, what is required is that the reasons show that the judge has seized the substance of the issue. In a case that turns on credibility ... the trial judge must direct his or her mind to the decisive question of whether the accuseds evidence, considered in the context of the evidence as a whole, raises a reasonable doubt as to his guilt (para 23). Charron J. went on to dispel the suggestion that the trial judge is required to enter into a detailed account of the conflicting evidence: Dinardo, at para 30. The degree of detail required in explaining findings on credibility may also, as discussed above, vary with the evidentiary record and the dynamic of the trial. The factors supporting or detracting from credibility may be clear from the record. In such cases, the trial judges reasons will not be found deficient simply because the trial judge failed to recite these factors. [33] In summary, a trial judge is given considerable latitude in explaining his or her findings of credibility in reasons, although the judge may be required to explain why he or she has found the evidence of one witness more credible than that of another when the evidence conflicts on a point that is central to the issue before the court. The appellate court is also entitled to determine whether the judges reasons, when appearing ill-explained, are clear from a review of the record. [34] How do these principles apply here? As the authorities indicate, it is a rare case where a trial judges assessment of credibility will be interfered with due to an absence of reasons. Here the trial judge came to the general conclusion that Stromners evidence was credible, having been delivered

Page: 9

in both a forthright and fair manner, without exaggeration, and she used that evidence to conclude that Davis had assaulted Stromner at the police car with a knife a key element in all three charges. The evidence of Giffen, Thomas and Debeurs, however, seemed to contradict Stromners evidence on this point. [35] The trial judge did acknowledge, in a general fashion, that there was conflicting evidence about the events as they unfolded. She stated: There were many different observations from many different individuals. That is not surprising. Witnesses observed these events unfolding from different vantage points, at different starting points, focussed on different things at different times. [ARD F03/1.20-24] [36] While it would have been preferable that the foregoing disagreement among witnesses on a key point had been specifically discussed and explained by the trial judge, a review of the record indicates the path she used to make her findings on credibility. The trial judge noted that Stromners account was supported by the evidence of an eyewitness. In fact, it was confirmed, in most important respects, by two witnesses who were close to the scene and may have had a better view than other civilian witnesses who were some distance away. Grace Knittle, an employee of Canada Post, was following behind the police car in a step-van as Stromner followed the appellant down 119th Avenue NW. She gave this evidence about what happened when the parties got to the end of the road [transcript at 328]: A And so when the man got to the end of the road, the man got off his bike and the police car was behind him, and the man jumped off his bike and came up to the police car as the policeman was getting out with the knife in his hand, and I believe he was pushing with both hands the door back closed when the officer was trying to get out; and then he just backed up a bit, and the officer got out and drew his gun and told him to drop the knife, many times to drop the knife, drop the knife, and just kinda kept walking, turning around, walking, turning around, with the knife up in the air sometimes, down, up, down: and then he continued walking towards the McDonalds on the other side of the road, and the policeman pepper sprayed him I believe right in the face, and it didnt really phase him. He just kept walking and turning, and the police officer continued to tell him to drop the knife, drop the knife. He didnt. And then they continued on, they crossed the street; and then at the end near the McDonalds parking lot, the police officer shot him. And then at first, I

Page: 10

thought he missed because he still didnt, didnt go to the ground or anything, but then, then he did. Thats what I saw. Q A Okay. Can you describe the knife? I thought it was a butcher knife, a very big knife.

[37] Another civilian witness, Venus Parkman, a home care nurse, was driving her vehicle and exiting the Abbotsfield Mall eastbound, in order to turn left onto Abbotsfield Road NW, at the time of the alleged assault. She described the following scene transpiring to her left [transcript at 359]: Then the boy or the young man, he dropped his bike, and he charged at the car, and he came right up to the beside the cop car door. And I dont know if they talked or whatever, but then about a couple of seconds later, probably about 10, 15 seconds, he backed away and went back to his bike ... [38] Thus, both of these witnesses gave evidence that the appellant initiated a confrontation with Stromner in the police car before he could get out of the vehicle. While the trial judge did not articulate which of these witnesses she was referring to, when she said she found support for Stromners story in the evidence of an eyewitness, it is clear that the essential aspects of Stromners testimony, that Davis confronted him at the door of the police car while in possession of a knife, was supported by the evidence of other credible witnesses who were in a good position to see what was going on. The trial judge was entitled to accept this evidence, as corroborative, and reject the evidence of the other witnesses whose vantage points and perceptions were different. The path to her conclusion is apparent from the record. [39] Davis also complains that the trial judge did not explain how she reconciled the various accounts from the civilian witnesses, about how he was holding the knife, with Stromners version. In our view, however, the trial judge was not obliged to set out what each witness said, and then attempt to reconcile the conflicting versions. As the trial judge noted, the evidence of the civilian witnesses on this point diverged to the extent that it was virtually useless. The trial judge stated: No witnesses described Mr. Davis handling the knife in exactly the same way. Some said he waved the knife over his head in one hand; at least one said he held it straight over his head in both hands; some did not see him wave it over his head at all; one described lethargic choppling motions; and one described forward thrusting motions, after which Mr. Davis uttered, Bang. Whatever else they saw, all agreed that notwithstanding Constable Stromners repeated direction to do so, Mr. Davis did not drop the knife.

Page: 11

[40]

It follows that this ground of appeal must be dismissed.

B. Ground Two Excessive use of force [41] This ground of appeal does not challenge the facts and law upon which the convictions for assault were based. Rather, it involves the conduct of the police officer in apprehending Davis after the assault occurred. Davis alleges that he need not have been shot, meaning that excessive force was used, thereby breaching his section 7 Charter right not to be deprived of security of his person, except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice. Furthermore, Davis submits that his section 12 Charter right not to be subject to any cruel and unusual treatment was breached. We note that if the police use excessive force in apprehending a person, and it results in a Charter breach, then the remedies available include a stay in extreme and extraordinary situations: R v Walcott, [2008] 57 CR (6 th) 223 (Ont SCJ). Alternatively, a remedy may be given at the sentencing stage (R v Nasogaluak, 2010 SCC 6, [2010] 1 SCR 206), or the misconduct may give rise to an award of damages (Crampton v Walton, 2005 ABCA 81, 363 AR 216). [42] Here, the gist of the appellants submission is that the trial judge misplaced the onus or burden of proof in stating that Davis bore the burden on a balance of probabilities to demonstrate that Constable Stromner did not reasonably believe that force was necessary to preserve himself or others from death or grievous harm and the he could have prevented Mr. Davis flight by reasonable means less violent (ABD 11/24-27). Davis acknowledges, and it is trite law, that the accused has the onus in a Charter application of proving a breach of his rights on a balance of probabilities. He submits, however, that where a police officer uses lethal force against a civilian, and relies on section 25(3) of the Criminal Code to justify his actions, then the accuseds burden is discharged once it is shown that he was subjected to the use of force causing him grievous harm. An evidentiary burden then falls upon the Crown to prove that the force was reasonable in all the circumstances and thereby justified by section 25 of the Code. In this case, he argues, he met the onus by showing that he suffered grievous bodily harm through the use of lethal force. It was then up to the Crown to show that the use of lethal force was justified under section 25. Davis seeks a new trial, and if a Charter breach is then proved, the trial Court will determine the appropriate remedy. [43] We agree with Davis that the Crown has the evidentiary burden of showing that section 25 of the Code has been met when it relies upon that provision to justify the use of force in circumstances such as those in the case at bar. The section is designed to protect those engaged in law enforcement from civil and criminal liability when they are required to use force in performing their public duties. It is clear, however, that when the section is invoked in this context, the burden falls on the person seeking to rely on the sections protection to prove that it applies. This was set out in Chartier v Greaves, [2001] OJ No 634, an action against two police officers for assault. Power J held at para 64, subnote (c): The onus of proving that the force used was not excessive lies on the police officers. Put another way, the onus on a plea of justification in the use of force lies on him who asserts it.

Page: 12

[44] This Court came to a similar conclusion in Crampton v Walton, 2005 ABCA 81, 363 AR 216, in applying subsection 25(1). The court noted, at para 14: As Mr. Crampton established the assault and the resulting injury, the police had to prove the assault was justified under s. 25(1). Imposing the burden in this fashion makes sense, as it is the police officer who is best suited to call evidence regarding his subjective intent, as well as any surrounding evidence demonstrating the objective reasonableness of that intent. [45] This reasoning is even more compelling when dealing with subsection 25(3), the applicable subsection in this case. While subsection (1) provides a positive right to use appropriate force when required, subsection (3) removes justification for the use of deadly, or potentially deadly, force unless the person using the force believes on reasonable grounds that it is necessary for the selfpreservation of the person or the preservation of anyone under that persons protection from death or bodily harm. [46] The trial judge distinguished the civil and disciplinary cases cited to her, in which the police were found to bear the onus of proving the application of section 25, on the basis that the overall burden in this case lay with the appellant to prove a breach of his Charter rights, on the balance of probabilities, through the use of excessive force. In our view, there is no good reason to distinguish these cases on this basis. The Supreme Court did not do so in Nasogaluak when it applied the objective/subjective test found in Chartier to an allegation the police had used excessive forced in making an arrest. In Nasogaluak, the police officer was not charged with misconduct but, as in the case before us, the police were relying on section 25(3) to repel the suggestion they had used excessive force in making an arrest. [47] Notwithstanding that the overall burden is on the person alleging a Charter breach, the situation is similar to a civil case where the overall burden lies with the plaintiff. Nonetheless, the law imposes an evidentiary burden on the defendant to prove the application of section 25, where he seeks to use it to justify his conduct. Although not completely analogous, this is also similar to the burden placed on the Crown in an application under section 8 of the Charter. Once an accused shows that a search was unlawful, the burden falls to the Crown to show that the search was nonetheless reasonable. This does not reverse the overall burden of proof on the Charter application, which remains with the accused. It just places an evidentiary burden on the Crown with respect to this aspect of the matter. [48] The trial judges misstatement of the law with respect to onus, however, does not determine the issue before us. Nothing turned on that issue in this case. The police called their evidence and the issue was fully argued. The Crown did not rely upon the failure of Davis to adduce evidence on the issue. In end result, the trial judge concluded: Constable Stromner did not issue a warning, but I conclude on the evidence before me that, on a balance of probabilities, he was justified in acting as he did and did not breach Mr. Davis s. 7, 9 and 12 rights.

Page: 13

[49] This passage clearly indicates that whatever the judge said about the appellants obligation to disprove the application of section 25, she found in fact that Stromners use of force in this instance was justified. In doing so, she relied upon the principles set out in Nasogaluak, at para 32, that the allowable degree of force to be used remains constrained from the principles of proportionality, necessity and reasonableness. [50] We have also considered whether the trial judge determined that the police officers belief was objectively reasonable, as she did not expressly say so. The test was described in Nasogaluak at para 34: Section 25(3) also prohibits a police officer from using a greater degree of force, i.e. that which is intended to likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm, unless he or she believes that it is necessary to protect him - or herself, or another person under his or her protection, from death or grievous bodily harm. The officers belief must be objectively reasonable. This means that the use of force under 25(3) is to be judged on a subjective objective basis (Chartier v. Greaves ... at para. 59. [51] Here the trial judge accepted Stromners subjective belief that he had no other choice, at the point of the final confrontation, than to shoot. Otherwise the appellant would soon reach a point where he was mingling with the public, putting bystanders in danger, and restricting Stromners options to protect public safety. She also tested the objective nature of that belief, by examining whether Stromner could have used other means, such as circling or issuing a warning, to prevent the appellants entry into an area where the public might be threatened. She concluded that these options were neither plausible nor required under the circumstances, and she noted that Stromner had already tried to get the appellant to drop the knife by using other less intrusive means, such as the pepper spray, all to no avail. [52] Nevertheless, the shooting took place at the back of McDonalds, separated from public access by a hill and a cement retaining wall. There were no members of the public present in the immediate area. Davis had stopped moving away from Stromner and had turned to face him. Unknown to Stromner, help in the form of two police officers, one equipped with a taser, was only seconds away. Indeed, both officers were at the scene before the appellant had fallen from his injuries. The trial judge did not comment on this evidence. [53] The record discloses, however, that the trial judge had evidence before her of a possible imminent threat to public safety if Davis continued in the general direction that he was going. She accepted Stromners evidence that he did not hear police sirens, and that he was unaware that help was about to arrive. Further, in direct examination, Stromner gave the following factual evidence with regard to the presence of people in the area, which supported his subjective belief:

Page: 14

Q. And did you know whether McDonalds was open at this time of day? A. Yes Maam, it was and I was just talking to people in the area, and I could see people coming and going from the restaurant and there was cars in the drive-thru. [transcript 132, lines 38-40] ... Q. Okay. Then what happened? A. The accused walked onto McDonalds parking lot property which is the which would be the east side of the McDonalds, the back of the restaurant. Q. M-hm. A. And its actually raised up quite high. So were not where theres people yet, it is the people are in front, but were on McDonalds property. The accused turned around and faced me with the knife again. [transcript 134, lines 21-28] [54] Further relevant factual information is contained in his evidence concerning his subjective belief. Stromner gave the following answer to the question of why he chose to discharge his firearm: A. I feared for my life. I feared for the safety. I feared for the lives of the people in McDonalds. If this continued to the front of McDonalds where there was people, I may reach a point where I am unable to take any action with the maximum consideration for public safety. He was going in the direction of a group of people and we were almost there, and I felt that if he gets into the group of people, they I have waited too long to take action. [emphasis added] [transcript 135, lines 25-30] [55] The trial judge had already determined that Stromners evidence was credible and reliable, and other evidence did not contradict his evidence that Davis was moving into a populated area. Thus, there was evidence before her which, if believed, demonstrated that the police officers subjective belief was objectively reasonable. The trial judge rejected defence counsels specific suggestions that Stromner could have gone around Davis to prevent him from going into a populated area, finding that it is unlikely that would have been a safer alternative. The trial judge cited and relied upon Nasogaluak in her analysis of the allowable degree of force, and we are satisfied that she made her judgment on a subjective-objective basis.

Page: 15

VI. Conclusion [56] The appeal is dismissed.

Appeal heard on October 4, 2012 Memorandum filed at Edmonton, Alberta this 24th day of January, 2013

OBrien J.A.

McDonald J.A.

Page: 16

Fraser CJA (dissenting): I. Introduction [57] This appeal concerns the limits on a police officers use of deadly force in effecting an arrest. Under the law, police officers are accorded a significant degree of latitude in their use of force to complete an arrest, and appropriately so. Courts have often stressed that police actions cannot be measured to a standard of perfection but must be assessed in light of the dangerous and exigent circumstances in which the police often find themselves: R v Nasogaluak, 2010 SCC 6 at para 35, [2010] 1 SCR 206. However, police officers do not have an unlimited right to inflict harm on a person, much less deadly force, in the execution of their duties. Under s. 25 of the Criminal Code, police use of force is constrained by the principles of proportionality, necessity and reasonableness: Nasogaluak, supra, at para 32. Indeed, because of the latitude given to the police in exercising their duties, courts must be vigilant in ensuring that the limitations on the police power of the state that do exist are upheld. The rule of law binds everyone in Canada including the police: Dedman v The Queen, [1985] 2 SCR 2 at para 25. [58] In this case, a police officer intentionally used deadly force in arresting the appellant, Percy Walter Davis, a young Aboriginal man. Davis was charged with possession of a knife for a dangerous purpose, assaulting a police officer and assault with a weapon. At trial, the defence contended that the police officer who arrested Davis had breached several of Daviss Charter rights. The essence of the defence claim was that the force used by the police officer in arresting Davis two gunshots, one to Daviss neck and the other to his upper chest was excessive and therefore unjustified at law. The gunshots, from four metres away, to the biggest part of Daviss body where critical bodily organs are located were life threatening and therefore constituted deadly force: see Appeal Record (AR) 134/33-40, 135/1-10. The defence asked for an exclusion of evidence, a stay of proceedings or a remedy on sentencing. [59] The trial judge rejected the defence position. In concluding that Daviss Charter rights were not breached, the trial judge determined that it was Davis as the Charter claimant who bore the burden of establishing that the force used by the police officer was not justifiable under s. 25 of the Criminal Code. Thus, she declined to exclude the evidence or grant a stay of proceedings. She convicted Davis on all three counts. [60] The defence appealed the trial judges decision on three grounds. One was that the trial judge erred in her analysis of whether Daviss Charter rights were breached. I agree with the majority that the trial judge erred in law in concluding that Davis bore the burden of establishing that the use of deadly force was not justifiable under s. 25 of the Code. [61] However, I respectfully disagree with the majoritys conclusion that nothing turned on this error of law. It is apparent from reviewing the chain of reasoning followed by the trial judge that her error of law in misallocating the burden of proof tainted both her assessment of the evidence and the legal conclusions she reached. Put simply, the trial judge compounded the burden of proof error by

Page: 17

then failing to articulate and apply the proper test for determining whether the Crown had met the evidentiary burden imposed on it to establish, given the prima facie breach of s. 7 of the Charter, that the police actions were justified at law. [62] This error of law warrants a new trial in accordance with s. 686(1)(a)(ii) of the Code. This is not a case where the appeal can be dismissed under s. 686(1)(b)(iv) on the basis that the error did not prejudice Davis. Clearly, it did by improperly placing a burden of proof on him to prove a negative, namely that the police actions were not justified under s. 25. Nor can it be dismissed under s. 686(1)(b)(iii) on the basis that, despite this error of law, no substantial wrong or miscarriage of justice occurred. This is not a harmless error which had no impact on the trial outcome. Therefore, to rely on this curative proviso, the Crown must establish that there is no reasonable prospect that the verdict would have been different absent the error: R v Charlebois, 2000 SCC 53, [2000] 2 SCR 674; R v Khan, 2001 SCC 86, [2001] 3 SCR 823. It has not done so. It cannot be said that the application of the proper test would necessarily have led to the same result on the Charter application and thus, that the trial outcome was inevitable. II. Relevant Background Facts [63] The trial judge made a number of fact findings as to how events unfolded here. For purposes of this analysis, I take no issue with respect to certain fact findings the trial judge made. However, as explained below, I have concluded that the trial judges error in misallocating the burden of proof compromised the manner in which she assessed and interpreted critical aspects of the evidence. [64] I do not intend to review the facts in detail. Briefly, a police officer was dispatched to an area near an Edmonton shopping mall, Abbotsfield Mall, following a complaint about a youth riding around on his bike with a butcher knife. The police officer found Davis riding his bicycle down an avenue by the Mall and followed him down the street. He stopped and sounded his air horn to get Daviss attention. [65] After the police officer sounded his air horn, Davis turned to face the police officer and charged at the drivers side of the police cruiser with the knife raised above his head. The police officer ducked over to the passenger side covering his head with his arm. He managed to get his pistol out and unlatch his door. Davis, who had his knife in his hand, arm over head, then backed off, picked up his bike and began to walk away. He continued to walk away or back away as the police officer advanced. The police officer gave him repeated verbal instructions to drop the knife. At some point, Davis turned to face the police officer and the officer pepper sprayed him in the face. The pepper spray appeared to have no effect on Davis, who again began to walk away or back away from the officer. [66] When Davis had charged at the cruiser, the police officer had declared a 10-13 emergency on the radio, indicating that an officer was in distress and in need of immediate assistance. After he pepper sprayed Davis, the police officer downgraded the 10-13 emergency to a 10-17, indicating, according to the evidence of one officer, that assistance was needed, but not as urgently. Another

Page: 18

officer testified that the change to a 10-17 meant that the officer involved would not have considered the threat as urgent. [67] As Davis moved away from the police officer, the police officer held his gun in both hands, at eye level, pointed directly at Davis, and continued to instruct him to drop the knife. Davis did not drop the knife and continued to back away or walk away from the police officer. [68] Davis crossed the road to the centre median in the direction of the Mall. The police officer advised dispatch to get cars here now. CED on the double. By that, he meant a taser. The police officer testified that he was not going to let Davis get to people as long as he held the knife in his hand. He did not know when officers would arrive and he believed that if he did not take action, Davis would enter a populated area (a McDonalds restaurant) and his options for stopping Davis would be very limited. When Davis again stopped and turned to face the police officer, the police officer made the decision to shoot Davis without any warning. He shot Davis twice in rapid succession, as noted, once in the neck to the right of his Adams apple and once in the right chest. [69] Almost immediately, two officers arrived on the scene, one in a police car and the other on foot. Davis was taken to hospital and treated for life-threatening injuries. [70] The entire sequence of events from the time the police officer activated his air horn to get Daviss attention to the time of shooting was very short. Less than three minutes after the police officer declared the 10-13, he reported that an ambulance was needed and shots had been fired: Appeal Record Digest (ARD) F1/32-38. III. Analysis [71] Section 7 of the Charter provides that everyone has the right to life and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice. The alleged use of excessive force by a police officer in the exercise of the police power of the state can engage s. 7 if the interference with the persons physical or psychological integrity rises to the level of a threat to the persons life or security as contemplated under s. 7: Rodriguez v British Columbia (Attorney General), [1993] 3 SCR 519; Nasogaluak, supra, at para 38. [72] Where the police use deadly force against someone, this constitutes a serious infringement of that persons life or security. Accordingly, for this infringement to withstand Charter scrutiny, it must comply with the principles of fundamental justice. Disproportionate use of force or arbitrary action by police in the discretionary exercise of the police power of the state cannot fit within this limitation: see Canada (Attorney General) v PHS Community Services Society, 2011 SCC 44 at paras. 117, 127-136, [2011] 3 SCR 134 as to those circumstances in which the exercise of a discretion will not be consistent with principles of fundamental justice. Compliance with the principles of fundamental justice requires that deadly force be justified under the law. The applicable law is s. 25 of the Code which limits the police power of the state to use deadly force in a free and

Page: 19

democratic society. Providing that the use of deadly force complies with the limitations in s. 25, it will not violate s. 7. This presupposes that s. 25 is Charter-compliant, an issue that was not before us. [73] Under s. 25(1), a police officer is permitted to use as much force as is necessary to effect an arrest, provided that he or she is acting on reasonable grounds. However, there are further limitations under ss. 25(3) and (4) where the use of force is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm to a person to be arrested. In these circumstances, the police officer must believe that the force is necessary to protect the officer or another person under his or her protection from death or grievous bodily harm. That belief must also be objectively reasonable: Nasogaluak, supra, at para 34. Further, if force of that degree is used to prevent a suspect from fleeing to avoid a lawful arrest, the same limitations apply plus there is an additional limitation, namely that the flight could not have been prevented by reasonable means in a less violent manner. It is not surprising that Parliament has stipulated strict requirements to justify the use of deadly force by police. As McLachlin J (as she then was) wrote in R v McIntosh, [1995] 1 SCR 686 at para 82: Life is precious.... [74] The specific wording of the relevant portions of s. 25 follows: 25(1) Every one who is required or authorized by law to do anything in the administration or enforcement of the law (a) as a private person, (b) as a peace officer or public officer, (c) in aid of a peace officer or public officer, or (d) by virtue of his office, is, if he acts on reasonable grounds, justified in doing what he is required or authorized to do and in using as much force as is necessary for that purpose. ... (3) Subject to subsections (4) and (5), a person is not justified for the purposes of subsection (1) in using force that is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm unless the person believes on reasonable grounds that it is necessary for the self-preservation of the person or the preservation of any one under that persons protection from death or grievous bodily harm.

Page: 20

(4) A peace officer, and every person lawfully assisting the peace officer, is justified in using force that is intended or is likely to cause death or grievous bodily harm to a person to be arrested, if (a) the peace officer is proceeding lawfully to arrest, with or without warrant, the person to be arrested; (b) the offence for which the person is to be arrested is one for which that person may be arrested without warrant; (c) the person to be arrested takes flight to avoid arrest; (d) the peace officer or other person using the force believes on reasonable grounds that the force is necessary for the purpose of protecting the peace officer, the person lawfully assisting the peace officer or any other person from imminent or future death or grievous bodily harm; and (e) the flight cannot be prevented by reasonable means in a less violent manner. [75] For present purposes, I note that the argument before the trial judge proceeded on the basis that it was s. 25(4) that was engaged here. That is evident from the comments of the trial judge: see ARD F11/23-27. However, regardless of whether s. 25(3) or s. 25(4) is relevant in this context, the errors in the trial judges reasons apply equally to both. [76] At trial, the defence contended that the force the police officer used was excessive and that Daviss Charter rights were violated. In addition to its claim under s. 7, the defence argued that Daviss s. 12 right (the right not to be subjected to cruel and unusual treatment) was violated. [77] In concluding that the force used was not excessive, the trial judge stated that the burden of proof of a Charter violation rests with the party asserting that violation. That is a correct statement of the law as far as it goes. However, she wrongly determined that this meant that where excessive force is alleged, an accused bears the burden of proving that the force used was excessive. She put it this way at ARD F11/23-27: He bears the burden on a balance of probabilities to demonstrate that [the police officer] did not reasonably believe that force was necessary to preserve himself or others from death or grievous bodily

Page: 21

harm and that he could have prevented Mr. Daviss flight by reasonable means less violent. [78] I agree with the majority that this is an incorrect statement of the law. Once an accused has met the burden of establishing that the police used deadly force against him or her, this constitutes a prima facie breach of s. 7 of the Charter. The evidentiary burden then shifts to the Crown to prove that the force used was justified in the circumstances. The test as to whether the use of deadly force was justified requires a combined subjective - objective analysis: Nasogaluak, supra at para 34; also see R v Storrey, [1990] 1 SCR 241. The trier of fact must conclude not only that the police officer subjectively believed that the use of force was necessary in all of the circumstances to protect the police officer or others from death or grievous bodily harm, but also that this belief was objectively reasonable. [79] This being so, it would be unfair to impose on an accused the burden of proving a negative, namely that the deadly force was not justified. Evidence of the subjective belief of the police officer falls squarely within the exclusive knowledge of the police officer and similarly, evidence as to what was considered reasonably necessary in the circumstances from an objective viewpoint may well be linked to police practices and procedures. This evidence is not within either the ready knowledge or control of an accused. [80] I would add a word of caution. Where an accused establishes a prima facie Charter breach, it is not proper to speak of a burden being imposed on the police. Those cases that refer to the burden shifting to the police are civil ones in which the police were defendants: see eg. Chartier v. Greaves, [2001] OJ No 634 (QL) (SCJ) at para 64, subnote (c); and Crampton v. Walton, 2005 ABCA 81, 363 AR 216 at para 7. However, in a criminal trial, the police are neither parties to a prosecution, nor defendants. Where an accused establishes a prima facie breach of s. 7 of the Charter because deadly force has been used against him or her, what is at issue is the police power of the state. The evidentiary burden then shifts to the Crown to prove on a balance of probabilities that the police actions were justified in accordance with the limitations in s. 25 of the Code and thus in compliance with the principles of fundamental justice. [81] Therefore, once Davis established a prima facie breach of s. 7, the evidentiary burden shifted to the Crown to establish that the use of deadly force by the police officer complied with the limitations in s. 25. Accordingly, the trial judge erred in imposing a burden on Davis as the accused to prove otherwise. [82] As noted earlier, the majority concludes that this error of law was harmless and that nothing turned on that issue in this case. I cannot agree. The trial judges misunderstanding of the burden of proof had a significant negative effect on her assessment of the evidence and her ultimate conclusion on the police officers use of deadly force. [83] I begin with this. It is true that after the trial judge had discussed the failure of the police officer to issue a verbal warning before shooting Davis, the trial judge stated at ARD F15/13 -15:

Page: 22

[The police officer] did not issue a warning, but I conclude on the evidence before me that, on a balance of probabilities, he was justified in acting as he did and did not breach Mr. Davis s. 7, 9 and 12 rights. [84] However, where, as here, a legal conclusion rests on a faulty chain of reasoning, including a failure to identify and apply the proper legal test in assessing whether police actions were justified under s. 25, that conclusion may well be fatally flawed. That is so in this case. The trial judges analysis here was inadequate and incorrect. I offer three reasons for this determination. [85] First, as a matter of common sense, when a trial judge improperly imposes a burden of proof on an accused, it follows logically that this misallocation of the burden of proof will frequently taint a trial judges assessment of evidence. Why? Judicial analysis of a set of facts is usually influenced, if not dominated, by the trial judges understanding of where a burden of proof lies. An incorrect understanding may lead to a trial judges disregarding, or treating as neutral, evidence that would otherwise have significance and arguably operate in favour of the defence had the trial judge properly allocated the burden of proof. This kind of processing error is analogous to that which occurs when a trial judge has misapprehended the substance of material parts of the evidence: R v Morrissey (1995), 22 OR (3d) 514. Where a burden of proof has been misallocated, it too may negatively impact on the fairness of the trial. That is what happened here. The trial judge improperly discounted or ignored relevant evidence or failed to understand why certain evidence was relevant and essential in assessing whether the Crown had met the evidentiary burden imposed on it. I discuss some of this evidence below. [86] Second, as a direct result of the misallocation of the burden of proof, the trial judge failed to expressly advert to the need for the Crown to establish that the police officers belief that the shooting was necessary was objectively reasonable. To determine whether the police officers actions were justified under s. 25, the trial judge had to ask herself two questions. The first is whether the police officer himself believed that the use of force was necessary to protect him or others from death or grievous bodily harm. The second is whether that belief that deadly force was necessary to protect the officer or others from death or grievous bodily harm was objectively reasonable. While she addressed the first question, she did not properly address the second. [87] The trial judge zeroed in on the subjective state of mind of the police officer and whether he believed it was necessary to use deadly force to effect Daviss arrest. She found him to be a credible witness and she accepted that he feared for his life and for the lives of others. However, her focus on what the officer subjectively believed caused her to lose sight of the crucial issue of whether the Crown had established that the police officers actions met the objective standard imposed under s. 25. Indeed, the word objective is not mentioned even once in the trial judges reasons. [88] Had this analysis been undertaken, the trial judge would have assessed the element of necessity in the context of the facts on the ground. In this regard, the defence had argued at trial that

Page: 23

the police officer could have used other means to stop Davis such as circling behind him or issuing a warning before shooting. The way in which the trial judge dealt with those other options compellingly demonstrates how her incorrect premise as to burden of proof compromised her reasoning. In her view, the defence suggestion that the police officer should have considered these other options was informed by hindsight: ARD F15/7-13. [89] But in assessing whether the police officers belief that deadly force was necessary was objectively reasonable as the Code requires, it would not have been hindsight for the trial judge to consider whether other reasonable options existed short of shooting Davis twice in rapid succession: R v Aucoin, 2012 SCC 66 at paras 39-42. This is precisely the analytical exercise that a trial judge is required to undertake in determining whether the Crown has met the evidentiary burden imposed on it to justify the use of deadly force once the defence has established, as it did here, a prima facie breach of s. 7. [90] The trial judge failed to assess the use of deadly force from this perspective, no doubt as a result of her initial error as to burden of proof. That assessment would have included considering the implications of the police officer downgrading the threat that Davis posed as well as whether police back-up and the taser which the police officer had ordered were close at hand and would have sufficed to deal on a timely basis with Davis and any perceived threat. It would also involve considering whether the police officer should have heard what others plainly heard, namely the siren from another police car with back-up on the way to the scene as this too is relevant in determining whether the police officers belief was objectively reasonable. [91] The trial judge would also have had to consider whether it was objectively reasonable for the police officer to conclude that he would not have had other opportunities to stop Davis before he moved towards the public area by McDonalds short of shooting him when he did. On this last point, it is important to understand the evidence before the trial judge. The police officer had testified that he feared for the lives of the people in McDonalds. Davis was shot near the south entrance of a service road to the Abbotsfield Mall. The photos entered as an exhibit at trial reveal the following. There is a McDonalds restaurant near that entrance to the Mall service road, but the service road entrance borders the area at the back of the McDonalds and is below it by some distance. In other words, it is both behind and below the restaurant. Further, it is separated from public access by an embankment and a retaining wall that borders a set of stairs leading up to the parking area. The point is this. Even if there were people on the other side of the McDonalds restaurant, that is by the public area, they were some distance from where Davis was shot. More important, Daviss progress to the public area would have been slowed considerably by his need to ascend the stairs or climb up the embankment and over a concrete wall just to reach the restaurant parking lot. [92] This evidence whether there were other reasonable options open to the police officer short of employing deadly force goes directly to the issue of whether the Crown had established on a balance of probabilities that the police officers belief that deadly force was necessary was in fact objectively reasonable.

Page: 24

[93] In addition, the trial judge was obliged to determine whether it was objectively reasonable that the police officer believed that death or grievous bodily harm to the officer or others was imminent or foreseeable. On this point, the trial judge ought to have taken into account all the evidence including what the police officer stated when he was interviewed following the shooting. As part of that interview, he was asked whether Davis was pointing the knife at him when Davis turned around. The police officer stated: He had the knife up like this, and he he hes not hes not aggressive. He I cant say hes not aggressive: AR 244/24-25 (as quoted from Exhibit 45, page 21). The police officer also stated during that interview: I did not want the accused into a position where he could possibly injure or kill a member of the public: AR 135/34-35. [94] These statements by the police officer go not merely to the officers subjective belief but also to the question of whether the Crown had established on a balance of probabilities that it was objectively reasonable for the police officer to conclude that death or grievous bodily harm was imminent or foreseeable so as to make the use of deadly force necessary when he shot Davis. There is a critical difference between a belief that an accused might get into a position where he might possibly injure or kill a member of the public and the objectively justified belief that, at the time deadly force is employed, death or grievous bodily harm is actually imminent or foreseeable. In this regard, for the deadly force by police to be proportional to the force to which it is responding, the accused must then be using force that is intended, or is likely, to cause death or grievous bodily harm. None of this analysis occurred here. [95] Third, the trial judge erred in the way in which she dealt with whether the police officer ought to have issued a warning before shooting Davis. Again, this error is directly linked to her starting point error on the burden of proof. The defence had argued that Canadian law requires an officer to issue a warning, where feasible, before using deadly force. The trial judge noted that she heard much evidence on that point and it led her to conclude, and properly so in my view, that whether a warning is warranted depends on the circumstances. She then went on to explain why she had concluded that no warning was required in this case. She reasoned that Davis knew that the police officer was pointing his service revolver at him. She concluded that a warning was not warranted because a reasonable person would understand [the police officer] would use [his service revolver] if the circumstances warranted it. There was no other purpose in continuing to point his service revolver at Mr. Davis after Mr. Davis failed to comply with verbal direction to drop the knife. (ARD 14/ 36-39). [96] This reasoning is flawed. On this thinking, there would never be any need for a police officer to issue a warning before shooting to kill once the target failed to comply with a police direction. Moreover, this reasoning again demonstrates the errors flowing from the trial judges burden of proof error. She refers to a reasonable person understanding that the police officers continuing to point the gun would mean that it would be fired if the circumstances warranted it. But the question is not what a reasonable person would understand or not understand, nor what Davis should reasonably have understood from the police officers continuing to point the gun at him. The question is whether, in the circumstances here, a verbal warning was another reasonable option that

Page: 25

the police officer ought to have pursued before using deadly force against Davis. In other words, was it objectively reasonable for the police officer to have concluded that shooting Davis when he did without warning was necessary to protect the officer and others from death or grievous bodily harm? The trial judge failed to address this question because of her misdirection on the burden of proof. [97] In summary, as a result of the error in misallocating the burden of proof, the trial judges analysis of whether the use of deadly force was justified was conducted from the wrong perspective. As a consequence, at no time did the trial judge ever consider whether the Crown had established on a balance of probabilities that the police officers use of deadly force was justified at law. Reasonableness is not only a matter of what a judge in a calm and reflective environment with the benefit of hindsight might now think. But equally reasonableness is not only a matter of what the officer at the scene thought. The finality of deadly force demands both accessible and acceptable standards. As I have explained, the trial judge here failed to test the police officers subjective belief about the necessity for deadly force against the objective standard mandated by law. That failure means that her conclusion about whether the deadly force was justified cannot stand. [98] I recognize that even if a Charter breach is established, a question would still arise whether that breach would justify either staying charges that arose from Daviss actions prior to the breach, or excluding evidence relating to those charges. Or whether some other remedy, such as taking any such breach into account in sentencing, might possibly be appropriate. However, as I am of the view that this case should be re-tried, it is not appropriate for this Court to discuss potential just and appropriate remedies, if any, at this stage. The fact remains that it cannot be safely concluded that the errors here would not have had a material effect on the trial outcome. Nor can it be said that the starting point error as to burden of proof and the additional errors of failing to properly assess and relate the evidence to the correct test of justification for the use of deadly force were harmless to the resolution of the Charter application and thus, the trial outcome. This is so both with respect to whether a Charter breach occurred and if so, what remedies, if any, might, or should, properly flow from that. IV. Conclusion [99] For these reasons, I would allow the appeal and order a new trial.

Appeal heard on October 4, 2012 Memorandum filed at Edmonton, Alberta this 24th day of January, 2013

Authorized to sign for:

Fraser C.J.A.

Page: 26

Appearances: D.C. Marriot, Q.C. for the Respondent P.J. Royal, Q.C. for the Appellant

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Torts OutlineДокумент74 страницыTorts OutlineBaber Rahim0% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Air France v. GillegoДокумент3 страницыAir France v. GillegoVon Angelo SuyaОценок пока нет

- REMREV 2 SyllabusДокумент19 страницREMREV 2 SyllabusRichie SalubreОценок пока нет

- (DIGEST) Estrada vs. Sandigan Bayan 369 SCRA 394Документ1 страница(DIGEST) Estrada vs. Sandigan Bayan 369 SCRA 394RexОценок пока нет

- Gender Guidelines For Best PracticesДокумент21 страницаGender Guidelines For Best PracticesSlav KornikОценок пока нет

- People vs. EnriquezДокумент16 страницPeople vs. EnriqueztheresagriggsОценок пока нет

- GATCHALIAN PROMOTIONS TALENTS POOL, INC., Complainant, vs. ATTY. PRIMO R. NALDOZA, Respondent.Документ8 страницGATCHALIAN PROMOTIONS TALENTS POOL, INC., Complainant, vs. ATTY. PRIMO R. NALDOZA, Respondent.Xhin CagatinОценок пока нет

- People Vs VillacortaДокумент11 страницPeople Vs VillacortaFelix Gabriel BalaniОценок пока нет

- Tan Vs HosanaДокумент5 страницTan Vs HosanaVince Llamazares LupangoОценок пока нет

- Iacobucci ReportДокумент33 страницыIacobucci ReportEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Ward 12 CandidatesДокумент7 страницWard 12 CandidatesEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Vehicle For Hire Bylaw 17400Документ17 страницVehicle For Hire Bylaw 17400Edmonton SunОценок пока нет

- 2016 By-Election Voting Station LocationsДокумент1 страница2016 By-Election Voting Station LocationsEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Summary of AmendmentsДокумент3 страницыSummary of AmendmentsEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Bus Rapid Transit ReportДокумент2 страницыBus Rapid Transit ReportSlav Kornik100% (1)

- Edmonton Home Values, July 2015Документ2 страницыEdmonton Home Values, July 2015Edmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Farm and Ranch QAsДокумент11 страницFarm and Ranch QAsEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Alberta Taxpayers Nice or Naughty List - Final Fancy PDFДокумент2 страницыAlberta Taxpayers Nice or Naughty List - Final Fancy PDFEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Alberta Utilities Commission Finds TransAlta's Planned Outages Spiked Electricity PricesДокумент217 страницAlberta Utilities Commission Finds TransAlta's Planned Outages Spiked Electricity PricesEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- REALTORS Association of EdmontonДокумент1 страницаREALTORS Association of EdmontonEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Suter Agreed Statement of FactsДокумент44 страницыSuter Agreed Statement of FactsedmontonjournalОценок пока нет

- 2015-16 1st Quarter Fiscal UpdateДокумент16 страниц2015-16 1st Quarter Fiscal UpdateEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Oil Prices vs. Crime RatesДокумент4 страницыOil Prices vs. Crime RatescaleyramsayОценок пока нет

- Alberta AG Report, Oct. 2015Документ228 страницAlberta AG Report, Oct. 2015Edmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Magical Haida GwaiiДокумент1 страницаMagical Haida GwaiiEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Fragmented Systems Connecting Players in Canada's Skills ChallengeДокумент34 страницыFragmented Systems Connecting Players in Canada's Skills ChallengeEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Canadian Federation of Independent BusinessДокумент31 страницаCanadian Federation of Independent BusinessEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- A Report of The Public Interest CommissionerДокумент13 страницA Report of The Public Interest CommissionerEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Metro Line ChronologyДокумент4 страницыMetro Line ChronologyEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Alberta Crop ReportДокумент2 страницыAlberta Crop ReportEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Vehicle For Hire BylawДокумент23 страницыVehicle For Hire BylawEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Uber City Bylaw ProposalДокумент1 страницаUber City Bylaw ProposalEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- K Days ParadeДокумент1 страницаK Days ParadeEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Alberta Health Annual Report, 2014 - 2015Документ211 страницAlberta Health Annual Report, 2014 - 2015Edmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Ice District UnveiledДокумент14 страницIce District UnveiledEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- K Days ParadeДокумент1 страницаK Days ParadeEdmonton SunОценок пока нет

- Moisture Situation Update - July 7, 2015Документ6 страницMoisture Situation Update - July 7, 2015Edmonton SunОценок пока нет

- 045-Auxilio, Jr. v. NLRC G.R. No. 82189 August 2, 1990Документ3 страницы045-Auxilio, Jr. v. NLRC G.R. No. 82189 August 2, 1990Jopan SJОценок пока нет

- The Law Firm of Chavez v. Justice DicdicanДокумент3 страницыThe Law Firm of Chavez v. Justice DicdicanJon Joshua FalconeОценок пока нет

- Cases To Digest (Crim 1)Документ133 страницыCases To Digest (Crim 1)Admin DivisionОценок пока нет

- Documents 4th Court of Appeals - 1Документ10 страницDocuments 4th Court of Appeals - 1AbithsuaОценок пока нет

- Appellee Vs VS: en BancДокумент9 страницAppellee Vs VS: en BancKaye RodriguezОценок пока нет

- Ipc IДокумент18 страницIpc ISiddhant MathurОценок пока нет

- AjjuДокумент9 страницAjjuSuhel Altaf QureshiОценок пока нет

- The Accused Are Not Guilty Under Section 376 and 354 of Indian Penal Code, 1860Документ5 страницThe Accused Are Not Guilty Under Section 376 and 354 of Indian Penal Code, 1860Mandira PrakashОценок пока нет

- Ch3 ASIC V RichДокумент107 страницCh3 ASIC V Richpeter_cainОценок пока нет

- Secondary Victims and The Trauma of Wrongful Conviction: Families and Children's Perspectives On Imprisonment, Release and AdjustmentДокумент19 страницSecondary Victims and The Trauma of Wrongful Conviction: Families and Children's Perspectives On Imprisonment, Release and AdjustmentAntonet CabtalanОценок пока нет

- 6 01 Requirement of Voluntary Act or OmissionДокумент18 страниц6 01 Requirement of Voluntary Act or OmissionlegalmattersОценок пока нет

- Ovitz V Fireman's Oct. 26 MSJ OrderДокумент3 страницыOvitz V Fireman's Oct. 26 MSJ OrderTHROnlineОценок пока нет

- People Vs SilvaДокумент7 страницPeople Vs SilvaKimОценок пока нет

- Ejectment JurisprudenceДокумент17 страницEjectment Jurisprudenceeds billОценок пока нет

- Evidence ReviewerДокумент18 страницEvidence ReviewerMichelle Marie TablizoОценок пока нет

- Political Law ForeverДокумент8 страницPolitical Law ForeverOly VerОценок пока нет

- Anil Gupta v. Kunal DasguptaДокумент17 страницAnil Gupta v. Kunal Dasguptabluetooth191Оценок пока нет