Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

My Interview With Gary Hamel, On The "Management Revolution"

Загружено:

Vikram KhannaОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

My Interview With Gary Hamel, On The "Management Revolution"

Загружено:

Vikram KhannaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

10 the raffles conversation

THE BUSINESS TIMES WEEKEND SATURDAY/SUNDAY, OCTOBER 6-7, 2012

THE BUSINESS TIMES WEEKEND SATURDAY/SUNDAY, OCTOBER 6-7, 2012

the raffles conversation 11

not where you are sitting right now. You need to go wherever it is, and see how things are changing. Two, if you want to avoid being held hostage by the past, you cannot give the old guard full control over resource allocation. Because they will always want to invest in what they know. Think of it this way: Silicon Valley has thousands of angel investors, hundreds of venture capitalists. What would happen if there was only one venture capital company in Silicon Valley and it was led by Bill Gates? A lot of the new companies we have today would never exist. If you look at the recent history of Microsoft, Bill Gates was a sceptic on the Web, on the e-reader, on digital music. In every single case when he had the opportunity to invest early and support it, he didnt. Its not so much his fault, because these were new things and maybe he didnt understand them. The point is that in a lot of large organisations, resource allocation works the same way as it worked in the Soviet Union. People have to fight for resources through several layers of management and then finally, somebody at the top says: Were going to invest, or were not going to invest. There should also be no monopoly on the allocation of capital. If I am a young employee and I have a new idea, there should be multiple places I can go to in an organisation to compete for funding. Because if I can only go to one person and that persons biases are all grounded in the past, the company will always miss the future. What you typically find happening today is that by the time an opportunity or problem is so big that it becomes obvious to the CEO that the company must invest in it, its too late. If Intel now goes: Wow, there are going to be a lot more mobile devices in the world than PCs, and theyre going to get smarter and smarter, and this is really the future, by the time it becomes obvious to the person at the top, the game is over. And its already over for Intel, he suggests: ARM Holdings has won. Theyre the British company that does most of the chip design for these mobile devices. Lesson Three for future-minded CEOs, according to Dr Hamel, is that spending big is not always smart. Low-cost experiments are likely to get better results. There is often a mistaken assumption that the way you win the future is to bet bigger than everybody else rather than try things more cheaply than everybody else. Googles CEO Eric Schmidt put it very nicely, he told me once, our goal at Google is to try more things more cheaply than anybody else. Most of them will fail, but a few will work. Thats the mindset to have. If you look at the companies that grew up on the Web, all of them started out dirt-poor. Some had a few thousand dollars from friends and family, or a few hundred thousand. For Dr Hamel, revolutionising management is not just an issue for companies, its something governments need to focus on as well. If you go around the world, you will hear governments say: We need to upgrade skills, we need more venture capital, we need better links between universities and companies, we need better infrastructure, we need to be more conducive to inward investment. What you never hear them say is, we need to have a revolution in how we manage. I believe that the single biggest impediment to organisational performance today is management itself. It is the top down, hierarchical, disempowering, backward looking, incrementalist, inertial tendences that are imposed upon organisations. Theyre not inherently wrong, they were just designed to solve a different problem of how do we do the same things over and over again with greater efficiency, rather than how do we reinvent ourselves, how do we create the kinds of products and services that stand out in an era of hyper competition, how do we get people to bring the gifts of their imagination and creativity to work everyday so we can compete in the creative economy. Indeed, reinventing management should be a national competitiveness issue, he suggests. And the countries that practised it even if not as a matter of deliberate government policy have reaped rich dividends. There is a reason Britain and the United States led the industrial revolution and were the most powerful economies of the 19th and 20th century, he points out. It wasnt because they had natural resources Britain certainly didnt. But they were pioneers in social innovation. If you go back and look at all the things that got invented in this area: work design, pay for performance, capital budgeting, strategic planning, divisionalisation almost all of those were invented in Britain and the US, some in Germany and later, some in Japan. I dont think over the long term, an economy or country can be a superpower if its institutions are run along the lines of management 1.0 rather than management 2.0. Dr Hamels passion for the management revolution has led him to create a Web-portal called the Management Innovation Exchange (www.managementexchange.com), which showcases management innovations from around the world. Were using crowd-sourcing to invent new social technologies, he says. Anybody can go there and learn from from it. And its free.

ARY Hamels favourite word must be revolution. The title of one of his bestsellers on corporate transformation, where he urges managements to encourage insurgents is Leading The Revolution. One of its chapters is titled Go Ahead: Revolt! When he signs his latest book, he inscribes: Welcome to the management revolution! For this management guru, who has been rated as the most influential business thinker by the Wall Street Journal, mere incremental change is not enough at this time in history. He believes we have already moved beyond the knowledge economy to what he calls the creative economy. For companies, this means change must be deep and dramatic. And it must start at the top. With all of my heart, I believe that over the next decade, 20 years at most, we will see a revolution in how organisations are led and managed that is as profound as when we went from an agrarian society to an industrial society, he says, during our conversation at the Four Seasons Hotel. The analogy I use is this: for the average person who was alive in 1900, it would be hard to imagine a company that looked like the Ford Motor company, which took in iron ore at one end and Model T came out at the other end, 500,000 cars a year. There was no basis of human experience which suggested it could be done. Thats the dimension of the change were about to witness, he says. And what it needs, above all, is a revolution in management. A livewire character bustling with ideas, Dr Hamel was the keynote speaker at the SIM Annual Management Lecture in August. He has a new book out, entitled What Matters Now. One of its main messages is that most current forms of management are at best, hopelessly obsolete and at worst, dangerous. Management, or the way we lead, was invented 100 years ago to drive the variability out of human activity, he says. Because if you want to build an airliner or an automobile or a 20 nanometer chip, you have to do things with amazing precision, exactly the same way, over and over again. So we had to turn human beings into machines. It was an extraordinary accomplishment in social engineering. We succeeded in doing that. Overall it dramatically improved global prosperity. But I dont think that is the formula either the process or the organisation that will create most of the wealth in the future. For the management of the future, Dr Hamel takes his inspiration from Silicon Valley, California, which has been perhaps the worlds most celebrated hotbed of corporate innovation and where he also happens to live, even though he is on the faculty of London Business School. He believes the ecosystem of Silicon Valley, and the management methods practised there contain valuable lessons for companies everywhere. Silicon Valley is basically three markets, he explains. Its a market for ideas, a market for experimental capital and a

Gary P Hamel

Management expert, educator and author Born: 1954 Ph.D, Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, 1990 Since 1983: Visiting Professor of Strategic and International Management, London Business School Has also served as Visiting Professor of International Business at University of Michigan and Harvard Business School Consulted for companies including: General Electric, Time Warner, Nestle, Shell, Best Buy, Procter & Gamble, 3M, IBM, and Microsoft. Author of books: Competing for the Future (with C.K. Prahalad, 1996); Leading the Revolution (2000); The Future of Management (2007); What Matters Now (2012) CEO, Management Innovation Exchange, an online portal featuring progressive and innovative management practices from around the world

Champion of the management revolution

Management guru Gary Hamel talks to Vikram Khanna about why companies need a revolution at the top

market for talent. There is no CEO in Silicon Valley who says next year we will invest this much in biotech, this much in the social web, this much in whatever. The money simply flows to the best ideas. And I think that in the Web economy, traditional top-down organisations are going to have a hell of a hard time. They are just not fast enough, flexible enough or malleable enough. The challenge for many organisations, he suggests, is that they have to create something that looks more like Silicon Valley. He gives an example of one illustrious company (from Seattle, not Silicon Valley) that lost the plot and fell mightily from grace as a result. Think about Microsoft which was the richest company in the world, he says. They had billions of dollars in cash. They could have invested in anything. They were spending about 10 times as much on R&D as Apple. And yet they lost. They have been late to every major new trend in software in the last 15 years. They were late to the Web, late to Search, late to Software as a Service, late to the Cloud. How, with all that cash, could they manage to miss so much? The answer is that with all that cash, Microsoft became an enormous bloated bureaucracy where the responsibility for setting strategy and direction was concentrated at the top, among people who had all their emotional equity invested in the old model. The old model which represents probably the majority of companies in the world today has one fatal flaw, he points out. I believe that the reason why large centralised organisations will miss the future is that they have given a small number of people at the top the power to hold hostage the organisations capacity to change to their own personal willingness to adapt and change.

.PHOTO: AZIZ HUSSIN/ST

Or to put it another way, the simplest reason organisations fail to see the future is that their leaders fail to write off their own depreciating intellectual capital. They have a view of customers and technology thats out of date and they know its out of date. But they hang on to the past until the future overtakes them. Dr Hamel concedes however that, especially in rapidly changing industries, many companies face the genuine challenge of having to manage a lucrative legacy business, while at the same time moving into new areas. Its true, he says. When you are making money from your core business, anything new is dilutive to your current success. So why would anyone do that? Think of Intel, which has been a leader in semiconductors, and yet they have a negligible share in chips for mobile devices. And thats not even much of a stretch from the one to the other. But he has a response to the challenges such companies face: First, you need a leadership that can distinguish between something that might be a fad and something that is a wave of history. Mobile devices, or to take your industry, media, digital media and

having consumers control their own media experience are tides of history. You can debate when they will overtake you, but they will at some point. Or take universities. Traditional universities are built first, around a geographical locus. The idea is people come to us and so there is all that investment in bricks and mortar. Well, that doesnt make so much sense anymore. Two, they are built on the idea that they own their faculty. Well, with a lot of faculty members, their own brand is bigger than that of their institutions. They could go to an online platform like Prospero, put up their courses for thousands of people all over the world and make the money, if they like. Third, they have an assumption that they have a monopoly on granting degrees. That can change. One can imagine in the future an employer saying to a potential recruit: I can see you have taken these 20 classes and that I can see your grades and thats good enough for me. Employers may not care so much which university you went to, so long as you are competent. Dr Hamel believes that corporate leaders have a duty to look at emerging trends and to resist denying or discounting them. You should in fact be amplifying them, he says. You should be asking: where is this taking us? Where does this lead? There is a human tendency for denial. As Ive often said, companies dont miss the future because its unpredictable, they miss the future because its uncomfortable. So what specifically should corporate leaders do to future-proof their organisations? One, as a leader, you should take a few weeks a year and go wherever you need to go in the world to get a first-person experience of the future. Its probably

The simplest reason organisations fail to see the future is that their leaders fail to write off their own depreciating intellectual capital. They have a view of customers and technology thats out of date and they know its out of date. But they hang on to the past until the future overtakes them.

vikram@sph.com.sg

Вам также может понравиться

- Computer Laboratory Maintenance Plan and ScheduleДокумент5 страницComputer Laboratory Maintenance Plan and ScheduleJm Valiente100% (3)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Ilovepdf Merged MergedДокумент209 страницIlovepdf Merged MergedDeepak AgrawalОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Health Safety StatementДокумент22 страницыHealth Safety StatementShafiqul IslamОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Introduction Compression TestДокумент7 страницIntroduction Compression TestEr Dinesh TambeОценок пока нет

- Cold Rolled Steel Sheet-JFE PDFДокумент32 страницыCold Rolled Steel Sheet-JFE PDFEduardo Javier Granados SanchezОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Avaya Call History InterfaceДокумент76 страницAvaya Call History InterfaceGarrido_Оценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Acids and Bases Part 3 (Weak Acids) EdexcelДокумент2 страницыAcids and Bases Part 3 (Weak Acids) EdexcelKevin The Chemistry TutorОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

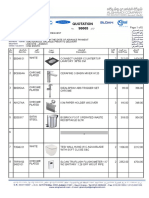

- Quotation 98665Документ5 страницQuotation 98665Reda IsmailОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- 2nd Term Physics ReviewerДокумент5 страниц2nd Term Physics ReviewerAlfredo L. CariasoОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2 Magnetic Effects of Current XДокумент25 страницChapter 2 Magnetic Effects of Current XPawan Kumar GoyalОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Design For X (DFX) Guidance Document: PurposeДокумент3 страницыDesign For X (DFX) Guidance Document: PurposeMani Rathinam RajamaniОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- 1SDA066479R1 Rhe xt1 xt3 F P Stand ReturnedДокумент3 страницы1SDA066479R1 Rhe xt1 xt3 F P Stand ReturnedAndrés Muñoz PeraltaОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Mainframe Vol-II Version 1.2Документ246 страницMainframe Vol-II Version 1.2Nikunj Agarwal100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- LM6 AluminiumДокумент4 страницыLM6 AluminiumRajaSekarsajjaОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- Libeskind Daniel - Felix Nussbaum MuseumДокумент6 страницLibeskind Daniel - Felix Nussbaum MuseumMiroslav MalinovicОценок пока нет

- Chap 08Документ63 страницыChap 08Sam KashОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- GIT CloudДокумент20 страницGIT CloudGyanbitt KarОценок пока нет

- Programmable Safety Systems PSS-Range: Service Tool PSS SW QLD, From Version 4.2 Operating Manual Item No. 19 461Документ18 страницProgrammable Safety Systems PSS-Range: Service Tool PSS SW QLD, From Version 4.2 Operating Manual Item No. 19 461MAICK_ITSОценок пока нет

- Kaltreparatur-Textil WT2332 enДокумент20 страницKaltreparatur-Textil WT2332 enFerAK47aОценок пока нет

- Brochure FDP - EG 16.08.2021-1-2-2Документ3 страницыBrochure FDP - EG 16.08.2021-1-2-2sri sivaОценок пока нет

- Inspection and Quality Control in Production ManagementДокумент4 страницыInspection and Quality Control in Production ManagementSameer KhanОценок пока нет

- Mandat 040310062548 21Документ379 страницMandat 040310062548 21Sujeet BiradarОценок пока нет

- Electrochemical Technologies in Wastewater Treatment PDFДокумент31 страницаElectrochemical Technologies in Wastewater Treatment PDFvahid100% (1)

- Project Based Lab Report ON Voting Information System: K L UniversityДокумент13 страницProject Based Lab Report ON Voting Information System: K L UniversitySai Gargeya100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- PDK Repair Aftersales TrainingДокумент22 страницыPDK Repair Aftersales TrainingEderson BJJОценок пока нет

- Pt. Partono Fondas: Company ProfileДокумент34 страницыPt. Partono Fondas: Company Profileiqbal urbandОценок пока нет

- UT TransducersДокумент20 страницUT TransducersSamanyarak AnanОценок пока нет

- BME (Steel)Документ8 страницBME (Steel)Mohil JainОценок пока нет

- Project of InternshipДокумент2 страницыProject of InternshipSurendra PatelОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- 1.5SMC Series-1864824 PDFДокумент8 страниц1.5SMC Series-1864824 PDFRizwan RanaОценок пока нет