Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Guenole Englert Taylor 2003 Article

Загружено:

m.roseАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Guenole Englert Taylor 2003 Article

Загружено:

m.roseАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Ethnic Group Differences in Cognitive

Ability Test Scores within a New

Zealand Applicant Sample

Nigel Guenole

Selector Group

Paul Englert

OPRA Consulting Group

Paul J. Taylor

Chinese University of Hong Kong

Given the widespread use of cognitive ability tests for Bobko, Switzer & Tyler, 2001). Cognitive ability tests have

employment selection in New Zealand, and overseas been found to be one of the most valid forms of predicting

evidence of substantial ethnic group differences in cognitive future job performance for a wide range of jobs (Schmidt &

ability test scores, a study was conducted to examine the Hunter, 1998). For this reason, some authors have

extent to which cognitive test score distributions differ as a suggested that abandoning their use in employment

function of ethnicity within a New Zealand sample. An decisions would result in a substantial sacrifice in workforce

examination of 157 Maori and 82 European verbal and productivity (Gottfredson, 1994; Hunter & Hunter, 1984).

numeric ability test scores from within a New Zealand Indeed, Schmidt and Hunter (1998) have argued that, since

government organization revealed sizeable and statistically cognitive ability tests have such high predictive validities,

significant mean differences between the two ethnic groups other selection methods should simply be considered as

on two of three cognitive tests evaluated. Specifically, Maori adding incremental validity to the selection decision once

scored, on average, 0.55 standard deviations lower than the cognitive ability of the candidate has been assessed,

European applicants on a measure of verbal reasoning, and implying that cognitive ability testing should be a major

1.79 standard deviations lower on a measure of numerical component of a thorough selection practice for many jobs.

business analysis. No mean difference was observed While more recent reviews of the validity of alternative

between ethnic groups for a test of General numeric selection methods suggest that, when estimates of range

reasoning. In light of these substantial differences on two of restriction and criterion reliability are standardized across

the three tests, we discuss strategies that organizations studies, structured employment interviews are at least as

using cognitive tests can employ to minimize adverse valid (Robertson & Smith, 2001), if not slightly more valid

impact on Maori applicants, as well as further research that (Hermelin & Robertson, 2001) than cognitive ability tests,

is needed. cognitive ability tests clearly remain one of the more valid

predictors of job performance.

Many organizations in New Zealand strive to achieve

multiple objectives with their personnel selection Cognitive ability tests play a prominent role in the personnel

procedures, including maximizing both predictive validity selection systems of many organizations both overseas and

and selection utility (i.e., cost effectiveness), as well as in New Zealand. In a recent survey of selection practices

achieving and maintaining an ethnically diverse workforce. within 100 randomly selected New Zealand organisations

These goals, however, can conflict, such that selection and 30 recruitment firms, Taylor, Keelry and McDonnell

methods that achieve one goal (e.g., predictive validity) (2002) found that almost one-half of the organisations

work against another goal (e.g., diversity). Overseas sampled use cognitive ability tests for selecting managerial

research suggests that a cognitive ability test s such an personnel - over twice the proportion used a decade ago

example of a selection method that supports one goal at the (Taylor, Mills & O'Driscoll, 1993) - and that almost two-thirds

expense of another (Huffcutt & Roth, 1998; Roth, Bevier, of recruitment firms use cognitive tests in selection. In fact,

New Zealand Journal Of Psychology Vol. 32, No.1, June 2003 1

the use of cognitive tests in personnel selection is now programs aimed to decrease social and economic disparity

greater in New Zealand than in many other countries, between Maori and non-Maori. If differences in the

according to a recent cross-national survey of staff selection distributions of occupational cognitive ability test scores

practices in 18 countries. This survey found that the between Maori and Europeans are near-zero (i.e., so small

prevalence of cognitive ability test use in New Zealand was as to have no practical significance), employers can use

greater than all but three other countries (Ryan, McFarland, such tests with the confidence that doing so will result in no

Baron & Page, 1999). adverse impact on achieving an ethnically diverse

workforce. If, on the other hand, substantial differences in

The value of cognitive ability testing for employee selection cognitive test scores are found, as they have been

does not, however, come without costs and some overseas, then organizations wishing to employ an

controversy. In the United States, for example, the use of ethnically diverse workforce must carefully consider whether

cognitive ability testing has been found to adversely impact and how to use such tests. The purpose of the present

African American and Hispanic applicants as a result of study was to investigate whether ethnic group differences

substantial differences in mean test scores (Sackett, exist among a sample of New Zealand job applicants, using

Schmitt, Ellingson and Kabin, 2001). Large-scale meta- historical recruitment data from an organisation that had

analyses have confirmed that African Americans score administered cognitive tests as part of their staff selection

approximately one standard deviation lower than Whites on procedure.

measures of quantitative ability, verbal ability, and

comprehension and that similar, and slightly smaller Method

differences (.7- .8 standard deviations) have been found Participants

between Hispanic and White applicants (see, for example, Archival test score data were available from a large New

Roth, Bevier, Boko, Switzer, & Tyler, 2001). Consequently, Zealand government organisation on applicants who had

where staff selection is based largely on cognitive ability test completed one or more of three cognitive ability tests while

scores, members of affected minority groups, such as applying for professional level positions, such as analysts,

African Americans and Hispanics in the USA, receive fewer senior analysts, or finance positions.

employment opportunities than Whites and some other

minority groups (Scientific Affairs Committee, 1994). This Participants in this research were applicants for analyst,

situation has led to a dilemma in the USA, in which relying senior analyst, and finance positions. The data used were

on cognitive ability tests has been seen by many historical, and were collected as part of the recruitment

organisations and researchers as sensible from the process. The testing for the candidates in this analysis

perspective of maximizing predictive validity, but doing so occurred over the period 1997-2001, including test scores

threatens the achievement of social objectives, such as for 239 candidates. These included 76 Maori male test

overcoming past social inequities, pluralism, and creating an scores, 74 Maori female test scores, 40 European male test

ethnically diverse workforce (Sackett & Wilk, 1994; Sackett scores, 39 European female test scores, and 10 scores (7

et al., 2001). Maori and 3 European) of unknown gender. The breakdown

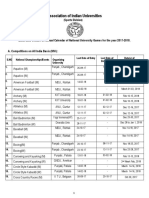

for each test is presented in Table 1.

While much research has been conducted in the United

States on ethnic differences on cognitive tests used in For the purposes of this research, job candidates were

employment selection, we know of no prior published classified as Maori if they had identified themselves when

research on the topic in New Zealand. Such research is applying as either Maori or Maori and any other origin,

important, given both the prevalence of cognitive testing for including European. Only candidates who indicated solely

employment in New Zealand, and government policy New Zealand European heritage were classified as

Maori European

Test Male Female Gender Unknown Male Female Gender Unknown

49 6 27 3

Verbal reasoning test 109 19.28 5.35 55 22.2 5.09 .55* .17 .22 - .89

Numerical business analysis test 19 8.21 3.34 10 14.90 4.43 1.79* .46 .85 - 2.72

General numerical reasoning test 29 14.72 5.76 17 14.76 5.55 .01 .31 - .61 - .62

New Zealand Journal Of Psychology Vol. 32, No.1, June 2003 2

European for the purposes of this research. Excluded from

this analysis were all test scores for candidates who While the present study identified ethnic differences in test

indicated an ethnic origin other than NZ European, or Maori scores, these results do not necessarily constitute test bias.

and any other ethnic origin (that is, any ethnic origin other Test bias is observed when systematic differences are

than that identified for inclusion in this analysis), as sample found between ethnic groups not only in mean test scores,

sizes were inadequate for meaningful analysis. but also in how tests predict job performance ratings. For

example, the verbal analysis test would only be considered

Given that the focus of this paper is on mean differences in biased if it was found to differentially predict job

test scores, we have not examined employment offer data. performance for Maori and European applicants (e.g. on

Consequently, inferences about whether adverse impact average, Maori scored lower on the test but performed the

resulted in this particular organisation are impossible to job just as effectively as Europeans).

identify. Any adverse impact is likely to have been

minimized by the existing recruitment approach that In order for evidence of test bias to be established,

provided equal weighting to structured employment additional information is needed on applicants' actual job

interviews, cognitive testing, and work sample tests performance once employed, so that differences in

(provided ethnic differences were not as prominent on these regression slopes and intercepts can be assessed when job

other recruitment methods). performance ratings are regressed on test scores within

ethnic groups. Job performance ratings were not available

As the data were from a government organisation, all for the present study, and so we were unable to explore

positions were advertised in external newspapers, jobs evidence of test bias in the present study. While overseas

websites, or both. However, information with regard to research both in the area of scholastic achievement and job

whether candidates were internal or external was performance indicates that tests of cognitive ability predict

unavailable. Ideally. In future research, this variable should equally well across ethnic groups -despite the fact that

be controlled. This would minimise any chance that results sizeable mean group differences exist (Roth et al., 200 I),

observed are due to different ethnic composition of the we know of no data published to date on test bias in New

internal and external samples, if, for example, internal Zealand. This is an important area in need of future

candidates have an advantage over external candidates. research.

Findings from overseas research suggests that ethnic Practical Significance of

differences in cognitive ability test scores are associated Mean Test Score

with similar (though less pronounced) ethnic differences in Differences

other selection methods that have a large cognitive Regardless of whether mean test score differences found in

component, such as in-basket exercises within assessment the present study reflect test bias, such differences would

centres (Goldstein, Yusko & Nicolopoulos, 2001). still lead to adverse impact for Maori as long as personnel

selection decisions are based, even in part, on scores on

Why a substantial mean difference was found for one such tests. If the present findings generalize to other

numerical test (the numerical business analysis test) but not organisations that place considerable weight on cognitive

the other (the general numeric reasoning test) is not entirely ability test scores in their staff selection processes, Maori

clear. The difference in findings for these two tests may be applicants, as a group, are less likely than Europeans to be

due to differences in the amount of business knowledge and selected.

experience required by the tests. The principle difference The practical implications of these findings can be

between the two tests is that the test on which no difference substantial, even if cognitive ability tests are simply used as

was observed does hot assume any business knowledge, a screening device, where those applicants who fail to

while the test on which differences were observed assumes achieve a particular cut-off score are removed from the

the person has had exposure to business terminology (e.g. selection process. For example, consider the case in which

net operating profit and gross profit). If Maori in the sample the standardized mean difference between Maori and

had less exposure to business terminology included in the European cognitive test scores is d = .5, similar to the ethnic

test on which differences were observed this lack of group difference we found for the verbal reasoning test in

experience may have accounted for the effect that was the present study (d = .55), which of the three cognitive

observed. tests assessed, resulted in a mean score difference in

New Zealand Journal Of Psychology Vol. 32, No.1, June 2003 3

between the differences found for the other two tests (1.78 A more recently developed strategy employed to arrive at a

and .01). If, with a mean group difference in selection test compromise between maximizing both validity and ethnic

scores of d = .5, a minimum cut-off score is established diversity when choosing cognitive ability tests for personnel

which allows 50% of the European applicants through, only selection is score banding. Banding involves defining a

30% of the Maori applicants would pass through to the next range of test scores that are treated as statistically

hurdle of the selection process. Furthermore, as the equivalent (Scientific Affairs Committee, 1994). Bandwidth

minimum cut- off score is set to be more stringent, the effect is usually either set arbitrarily or based on the standard error

becomes even more pronounced, e.g., if the test cut-off of the difference between scores, e.g., scores within 1.65

score is set at a point which allows only 10% of the standard errors of the top score in a band are considered to

European applicants through, the same mean group be equivalent (i.e., not statistically different at the .05 level

difference in test scores (d = .5) would result in a pass-rate of significance) from the top score. Hence those applicants

of only 4% of Maori applicants! falling within a band are considered equivalent on the

cognitive ability test and are then chosen based on other

characteristics. Such as scores on other assessments (e.g.,

Strategies for Minimizing interviews, personality tests, assessment centres, reference

Adverse Impact checks, or even ethnicity. While banding sacrifices some

Many occupational psychologists and organisations in New degree of validity (depending on the distance between

Zealand are concerned that their selection practices should scores at the top of the range), it can support the goal

not inadvertently disadvantage Maori, and so these findings achieving a more ethically diverse workplace provided that

present a dilemma for those who use cognitive ability tests decisions within each band are based on job-related

in making hiring decisions. Next we consider strategies that characteristics for which there are not ethnic group

have been recommended or used to minimise the adverse differences. Generally, score banding has become one of

impact of cognitive ability tests. the more accepted means of meeting diversity goals while

using cognitive ability tests for which mean ethnic group

One set of procedures that has been used by organisations differences exist (Sackett & Wilk, 1994).

(primarily overseas) involve within-group score adjustments. Score banding, however, has several serious drawbacks,

These include (a) providing bonus points on tests based on and has not been universally accepted. Critics argue that

ethnic group membership; (b) within-group norming (i.e., banding is logically flawed (Campion, et al., 200 I; Schmidt,

standardizing individuals' scores, or converting them to 1991), in that differences between scores within bands are

percentiles, based on the distribution of scores for the considered meaningless and thus ignored, but similar or

individual's ethnic group); (c) establishing different score even smaller score differences between bands are treated

cut-offs for different ethnic groups; or (d) filling quotas for as meaningful. Similarly, banding has been criticized as

positions established for each group using top-down being inconsistent with the fundamental premise of

selection (i.e., offering the position/s first to the highest occupational testing: namely the optimization of

scoring applicant/s) from separate lists of applicants. While performance prediction (Schmidt, 1991). The reduction in

none of these strategies maximize predictive validity as adverse impact achieved through banding is necessarily at

effectively as top-down selection from the entire group (i.e., the expense of using the test to most accurately predict

regardless of ethnicity), they all take advantage to some performance, and herein lays the dilemma for those using

degree of the test's predictive validity while at the same time cognitive tests for employee selection in New Zealand. With

they can achieve diversity objectives. Such methods, fairly large mean ethnic group differences, as found in the

however, are controversial because decisions are based, at present study, quite wide bands must be formed in order to

least in part, on ethnicity rather than merit, and while the achieve diversity objectives, but because band width is

legal implications of such procedures have not been tested associated with reductions in validity and hence utility, the

in New Zealand, they have been the subject of intense legal cost-effectiveness of using cognitive ability tests with wide

debate in the United States, where such forms of score bands becomes questionable.

adjustments based on ethnicity have been outlawed in the

Civil Rights Act of 1991 (Gottfredson, 1994; Sackett & Wiik, Another alternative strategy is to use, and place emphasis

1994). on, alternative selection methods that tap non- cognitive,

job-related constructs. This approach has recently been

advocated overseas (Sackett et al., 200 I), particularly in

New Zealand Journal Of Psychology Vol. 32, No.1, June 2003 4

light of the controversy surrounding test score banding than Maori and European applicants. For example, if the

(Campion et al., 200 I). Non-cognitive performance organisation short-listed a greater proportion of Maori

constructs, such as interpersonal skills, organizational applicants than European applicants using a measure which

citizenship behaviours and team-related behaviours, have correlates highly with cognitive test scores (e.g., education

been viewed as increasingly important in today's workplace level achieved), it is possible that the mean test score

(see, for example, lIgen & Pulakos, 1999), and these can differences found in the present study could have resulted,

largely be predicted by non-cognitive selection measures, in part, from differences in the short-listing practice, i.e., that

such as personality tests, bio data instruments, employment such differences may not have existed had short-listing

interviews, team-based exercises, and reference checks. practices been the same for both groups. Future research

For example, structured employment interviews have been should include measures of education level to explore this

found to have both high predictive validity (McDaniel, possibility.

WhetzeI, Schmidt & Maurer, 1994; Taylor & Small, 2002;

Wiesner & Cronshaw, 1988) and lower levels of ethnic The present study was based on three cognitive ability

group differences than either unstructured employment tests, and further research is needed on ethnic group

interviews or cognitive ability tests (Huffcutt & Roth, 1998). differences in New Zealand using other cognitive tests.

Similarly high levels of validity and low levels of ethnic group Perhaps more fluid measures of cognitive ability that do not

differences have been found for structured employment involve vocabulary or knowledge of business concepts,

interviews within New Zealand (Gibb & ("'Taylor, in press). such as the Ravens Progressive Matrices, would produce

To the extent that non-cognitive aspects of performance are smaller ethnic group differences while also predicting job

job related, the inclusion of such measures can both performance (Kline, 2000), and future research could

increase validity and reduce adverse impact. We note, investigate such measures.

however that the present results suggest that, to the extent

that measures of cognitive ability -either cognitive ability As mentioned earlier, further research is needed which

tests or other measures that have high levels of cognitive includes measures of job performance, in order to

saturation -are included in an organization’s selection determine whether cognitive ability tests yield biased

procedure, adverse impact will not be entirely removed. predictions of job performance. Future research might also

include measures of prior education and experience, which

could shed light on potential causes of observed

Limitations and Conclusions differences. Finally, with the growing use of personality tests

Limitations of the present study need to be considered when for personnel selection (Taylor et al., 2002), research is

interpreting these findings, and these limitations suggest needed on personality test score differences across ethnic

directions for future research on ethnic group differences on groups.

selection tests commonly used in New Zealand. The

present study was conducted within a single New Zealand Unfortunately, research on ethnic group differences on

organisation, and so these results should be considered occupational tests is difficult in New Zealand because of the

preliminary, and further research is needed in other settings, relatively small numbers of Maori and European staff within

including other jobs and in private-sector organisations. particular job families in single organisations. Stable

Such research would create a larger database, providing statistics require relatively large samples, and so meaningful

more stable estimates of group differences, as well the interpretation of such data is virtually impossible within most

opportunity to determine the extent to which differences as of New Zealand organisations. Consequently, the onus of

a function of job type and organizational setting. Overseas responsibility for such research must fall on the very large

research, for example, suggests that ethnic group organisations or on those firms that sell psychological tests

differences are even larger for jobs of lower complexity in New Zealand and who are able to conduct analyses

(Roth et aI., 2001). across organisations.

We were unable to obtain sufficient detail from the In conclusion, psychological tests and other selection

organisation on short listing procedures to preclude the methods playa critical role as gate-keeper for desirable

possibility that a short-listing process was employed that positions in organisations, and thus their use has important

resulted in substantial differences in the composition of social consequences to both organisations and individuals.

Maori and European candidates sitting the cognitive tests Understanding how such tests function in this gate-keeping

New Zealand Journal Of Psychology Vol. 32, No.1, June 2003 5

role is necessary for making informed decisions about which McOanicl, M. A., WhetZel, O. L., Schmidt, F. L.. & Maurcr,

methods are used, how they are scored, and how they S. (1994). The validity of employment interviews: A

should contribute to selection decisions. We hope that comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Journal

further research continues on this important topic. of,4pplied Psychology, 79.599-616.

Robertson. I. T., & Smith. M. (200 I ). Personnel selection.

References Roth. P.L.. Bevier, C.A.. Bobko. P., Switzer, F.S., & Tyler. P.

(200 I). Ethnic group differences in cognitive ability in

Comprehensive meta-analysis (Version 1.023) [Computer employment and educational settings: A meta-analysis.

software]. (1998). Englewood, NJ: BioStat. Personnel Psychology, 54. 297-330.

Ryan, A.M., McFarland, L., Baron, H., & Page, R. (1999).

Campion, .M.A., Outtz. J.L.. Zedeck, S., Schmidt. F.L., An international look at selection practices: Nation and

Kehoe. J.F Murphy, K.R., & Guion, R. (2001). The culture as explanations for variability in practice. Personnel

controversy over score banding in personnel selection: Psychology. 52,359-392.

Answers to 10 key questions. Personnel Psychology. 54.

149-185. Sackett, P, R. Schmitt, N. Ellingson, J, E., & Kabin, M, B.

(200 I). High-stakes testing in employment, credentialing,

Gibb, J.L., & Taylor. P.I. (in press). Past experience versus and higher education -Prospects in a post-affirmative action

situational employment interview questions in a New world. American Psychologist, 56. 302-318.

Zealand social service agency. Asia-Pacific Journal oj

Human Resources. Sackett, P. R.. & Wilk, S. I. (1994). Within-group norming

Goldstein, H.. W., Yusko, K.P., & Nicolopoulos, V. (2001). and other forms of score adjustment in pre-employment

..Exploring Black-White subgroup differences on managerial testing. American Psychologist, 49, 929-954.

competencies. Personnel Psychology. 5-1. 783-807.

Scientific Affairs Committee (1999). An evaluation of

Gottfredson, L, S. (1994). The science and politics of race banding methods in personnel selection. The Industrial-

norming. American Psychologist, 49, 955-963. Organizational Psychologist. 49,80-86.

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin. I. (1985). Statistical methods for Schmitt, F, I. & Hunter, 1, E. (1998). The validity and utility

meta- analysis. Orlando. FI: Academic Press. of selection methods in personnel psychology: practical and

theoretical implications of 85 years of research findings.

Hermelin, E., & Robertson. I.T. (2001). A critique and Psychological Bulletin, 12./, 262-274.

standardization of meta-analytic validity coefficients in

personnel selection. Journal of Occupational and Schmidt, F.L. (1991). Why all banding procedures in

Organizational Psychology, 7-1.253-277. personnel selection are logically flawed. Human

Performance, 4, 265-277.

Huffcutt, A. I., & Roth, P. L. (1998). Racial group differences

in employment interview' evaluations. Journal of Applied Taylor, P J., Keelty, Y., & McDonnell, B. (2002). Evolving

Psychology, 83,179-189. personnel selection practices in New Zealand organizations

and recruitment firms. New Zealand Journal of Psychology,

Hunter J.E., & Hunter R.F. (1984). Validity and utility of 3 J, 8-18.

alternative predictors of job performance. Psychological Taylor, P., Mills, A., & O'Driscoll, M. (1993). Personnel

Bulletin, 96, 72-98. selection methods used by New Zealand organisations and

personnel consulting firms. New Zealand journal of

Ilgcn. O.R., & Pulakos. E.O. (Eds.). (1999). The changing Psychology, 22, 19-31.

nature of performance: Implications of staffing, motivation

and development. San Francisco: Josscy-Bass. Taylor. P. 1., & Small, B. (2002). Asking applicants ".hat

they would do versus what they did do: A meta-analytic

Klinc:, P. (2000). Handbook of Psychological Testing (2od comparison of situational and past behaviour employment

cd.). England: Routlcdgc.

New Zealand Journal Of Psychology Vol. 32, No.1, June 2003 6

interview questions. Journal of Occupation and

Organizational Psychology. 75,277-294.

Wicsner. W., & Cronshaw. S. (1988). A meta-analytic

investigation of the impact of interview format and degree of

structure on the validity of the employment interview Journal

of Occupational Psychology. 61.275-290.

Notes:

1. We were unable to determine the particular job analysis

approach used by the organisation and test seller in order to

select the most appropriate battery of tests for the family of

jobs. i.e., whether the numeric test involving business

knowledge is job-related. Given the sizeable ethnic group Address for correspondense:

differences on this test, establishing the job-relevance of Nigel Guenole

such a test would have become important. PO Box 3218,

2. We were unable to obtain details of how test scores were Shortland Street Auckland,

used in selection decisions within the particular organisation New Zealand.

from which these data were collected. Email: n.guenole@selectorgroup.com

3. These estimates were based on figures presented by

Sackett & Wilk (1994).

New Zealand Journal Of Psychology Vol. 32, No.1, June 2003 7

Вам также может понравиться

- 15FQ ManДокумент72 страницы15FQ Manm.roseОценок пока нет

- Psytech TrainingДокумент41 страницаPsytech Trainingm.roseОценок пока нет

- 15FQ+ Sample ReportДокумент11 страниц15FQ+ Sample Reportm.rose0% (1)

- BPS Assessment Centre GuidelinesДокумент25 страницBPS Assessment Centre Guidelinesm.rose100% (1)

- Guidelines For 360 FeedbackДокумент19 страницGuidelines For 360 FeedbackDaniela LorinczОценок пока нет

- Level B PackДокумент19 страницLevel B Packm.roseОценок пока нет

- Psychological Testing IntroductionДокумент13 страницPsychological Testing IntroductionziapsychoologyОценок пока нет

- GRT1 Sample ReportДокумент4 страницыGRT1 Sample Reportm.roseОценок пока нет

- VMI Sample ReportДокумент4 страницыVMI Sample Reportm.roseОценок пока нет

- GRT2 Sample ReportДокумент4 страницыGRT2 Sample Reportm.roseОценок пока нет

- OIP+ Sample ReportДокумент9 страницOIP+ Sample Reportm.roseОценок пока нет

- TTB2 Sample ReportДокумент5 страницTTB2 Sample Reportm.roseОценок пока нет

- CRTB2 Sample ReportДокумент3 страницыCRTB2 Sample Reportm.roseОценок пока нет

- 15FQ+ Sample ReportДокумент11 страниц15FQ+ Sample Reportm.rose0% (1)

- Reasoning Tests Technical ManualДокумент78 страницReasoning Tests Technical Manualm.roseОценок пока нет

- Technical Test Battery ManualДокумент32 страницыTechnical Test Battery Manualm.roseОценок пока нет

- Occupational Interests Profile Plus Technical ManualДокумент47 страницOccupational Interests Profile Plus Technical Manualm.rose100% (1)

- Value & Motives Inventory Technical ManualДокумент32 страницыValue & Motives Inventory Technical Manualm.roseОценок пока нет

- Oppro: Occupational Personality Profile Technical ManualДокумент71 страницаOppro: Occupational Personality Profile Technical Manualm.roseОценок пока нет

- Clerical Reasoning Test Technical ManualДокумент37 страницClerical Reasoning Test Technical Manualm.rose100% (2)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- 145 Manual ChecklistДокумент4 страницы145 Manual ChecklistElLoko MartinesОценок пока нет

- Mark Scheme (Results) Summer 2016: Pearson Edexcel GCE in Economics (6EC02) Paper 01 Managing The EconomyДокумент18 страницMark Scheme (Results) Summer 2016: Pearson Edexcel GCE in Economics (6EC02) Paper 01 Managing The EconomyevansОценок пока нет

- Managing Primary Secondary SchoolsДокумент155 страницManaging Primary Secondary SchoolsAudy FakhrinoorОценок пока нет

- Career Management ProgramДокумент8 страницCareer Management ProgramLeah Laag IIОценок пока нет

- Oceania Art of The Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of ArtДокумент372 страницыOceania Art of The Pacific Islands in The Metropolitan Museum of ArtI. Elena100% (2)

- 908e03-Pdf-Eng Security BreachДокумент12 страниц908e03-Pdf-Eng Security Breachluis alfredo lachira coveñasОценок пока нет

- Sports Calendar 2017-18Документ11 страницSports Calendar 2017-18Charu SinghalОценок пока нет

- A B Keith (Ed) - Speeches and Documents On Indian Policy 1750-1921 Vol IIДокумент394 страницыA B Keith (Ed) - Speeches and Documents On Indian Policy 1750-1921 Vol IIfahmed3010Оценок пока нет

- SBN 1188 - LPG BillДокумент35 страницSBN 1188 - LPG BillJoy AcostaОценок пока нет

- Employee Involvement QuestionnaireДокумент3 страницыEmployee Involvement Questionnairehedo7100% (10)

- Conejo Top AttractionsДокумент2 страницыConejo Top AttractionsDemnal55Оценок пока нет

- Website Planning Template ForДокумент10 страницWebsite Planning Template ForDeepak Veer100% (2)

- Allama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad: (Department of Business Administration)Документ5 страницAllama Iqbal Open University, Islamabad: (Department of Business Administration)Imtiaz AhmadОценок пока нет

- Unit 2: Skills Test B: Dictation ListeningДокумент3 страницыUnit 2: Skills Test B: Dictation ListeningVanesa CaceresОценок пока нет

- Why Do People Travel?: Leisure TourismДокумент2 страницыWhy Do People Travel?: Leisure TourismSaniata GaligaОценок пока нет

- UcДокумент9 страницUcBrunxAlabastroОценок пока нет

- 2points 3points: Introduction and CONCLUSION (Background History/Thesis Statement)Документ2 страницы2points 3points: Introduction and CONCLUSION (Background History/Thesis Statement)Jay Ann LeoninОценок пока нет

- SUG532 - Advanced Geodesy Final ReportДокумент13 страницSUG532 - Advanced Geodesy Final Reportmruzainimf67% (3)

- 2020 GASTPE Orientation Letter To SchoolsДокумент3 страницы2020 GASTPE Orientation Letter To SchoolsAlfie Arabejo Masong LaperaОценок пока нет

- k12 QuestionnaireДокумент3 страницыk12 QuestionnaireGiancarla Maria Lorenzo Dingle75% (4)

- The Military Balance in The GulfДокумент50 страницThe Military Balance in The Gulfpcojedi100% (1)

- Kahoat - Reshaping Medical SalesДокумент4 страницыKahoat - Reshaping Medical SalesJatin KanatheОценок пока нет

- AOT Traffic Report-2018Документ252 страницыAOT Traffic Report-2018Egsiam SaotonglangОценок пока нет

- Earthquake Drill 3Документ17 страницEarthquake Drill 3Dexter Jones FielОценок пока нет

- IBPS RRB Office Assistant Exam Pattern: Get Free Job Alerts in Your Email Click HereДокумент9 страницIBPS RRB Office Assistant Exam Pattern: Get Free Job Alerts in Your Email Click Hereहिमाँशु गंगवानीОценок пока нет

- It's All About That DANCE: The D AnceДокумент3 страницыIt's All About That DANCE: The D AnceRyzza Yvonne MedalleОценок пока нет

- U3.Reading Practice AДокумент1 страницаU3.Reading Practice AMozartОценок пока нет

- Lean Assessment For Manufacturing of Small and MedДокумент5 страницLean Assessment For Manufacturing of Small and MedAmmuОценок пока нет

- Chapter 12 Quiz 1Документ4 страницыChapter 12 Quiz 1joyceОценок пока нет

- A Critical Review of Benedict AndersonДокумент7 страницA Critical Review of Benedict AndersonMatt Cromwell100% (10)