Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Global Health Initiatives and Health Systems: A Commentary On Current Debates and Future Challenges (WP11)

Загружено:

Nossal Institute for Global HealthОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Global Health Initiatives and Health Systems: A Commentary On Current Debates and Future Challenges (WP11)

Загружено:

Nossal Institute for Global HealthАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

WORKING PAPER SERIES NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges

Helen M. Robinson

Nossal Institute for Global Health, University of Melbourne

Krishna Hort

Nossal Institute for Global Health, University of Melbourne

John Grundy

Nossal Institute for Global Health, University of Melbourne

The Nossal Institute for Global Health

www.ni.unimelb.edu.au

KNOWLEDGE HUBS FOR HEALTH

Strengthening health systems through evidence in Asia and the Pacific

WORKING PAPER SERIES

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

ABOUT THIS SERIES

This Working Paper is produced by the Nossal Institute for Global Health at the University of Melbourne, Australia. The Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) has established four Knowledge Hubs for Health, each addressing different dimensions of the health system: Health Policy and Health Finance; Health Information Systems; Human Resources for Health; and Womens and Childrens Health. Based at the Nossal Institute for Global Health, the Health Policy and Health Finance Knowledge Hub aims to support regional, national and international partners to develop effective evidence-informed policy making, particularly in the field of health finance and health systems. The Working Paper series is not a peer-reviewed journal; papers in this series are works-in-progress. The aim is to stimulate discussion and comment among policy makers and researchers. The Nossal Institute invites and encourages feedback. We would like to hear both where corrections are needed to published papers and where additional work would be useful. We also would like to hear suggestions for new papers or the investigation of any topics that health planners or policy makers would find helpful. To provide comment or obtain further information about the Working Paper series please contact; niinfo@unimelb.edu.au with Working Papers as the subject. For updated Working Papers, the title page includes the date of the latest revision. Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges. First Published September 2011 Corresponding author: Helen M. Robinson Address: The Nossal Institute for Global Health, University of Melbourne hmro@unimelb.edu.au This Working Paper represents the views of its author/s and does not represent any official position of the University of Melbourne, AusAID or the Australian Government.

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

WORKING PAPER SERIES

SUMMARY

The recent establishment of a range of global health initiatives has transformed the landscape of development assistance for health by providing significant increases in funding through innovative financing mechanisms. Most global health initiatives have tended to focus on specific disease program interventions or outcomes, but some, notably the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI) and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM), also support health system strengthening. Given the volume of funds involved and the tendency to focus on vertical programming, global health initiatives have generated ongoing debate about their impact on the already fragile health systems of low-income countries (LICs) and their capacity to support health system strengthening. We provide a summary of the key issues in the debate, focusing on health financing and service delivery. We then highlight how an initiative launched within the broader global development sphere, that of the aid effectiveness agenda, is linked to global health initiatives and their interactions with health systems. We conclude by suggesting that those working in the area of health system strengthening need to understand the debates occurring at the global level, and to be aware of the tensions that relate to them. These tensions can be better managed through closer dialogue between health practitioners working at the global level and within countries.

See for example the agendas of the World Health Assembly and Executive Board during 2002 to 2008.

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges 1

WORKING PAPER SERIES

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

INTRODUCTION

Global health initiatives (GHIs) have emerged in recent years as a new type of organisation engaging in and influencing development assistance for health. Comprising partnerships between government, nongovernment, corporate and philanthropic actors, these initiatives have mobilised significant additional funds for health programs in middle-income countries (MICs) and LICs through a variety of innovative funding mechanisms (Marchal, Cavalli et al 2009; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2010). This substantial amount of financial resources has translated into a considerable scaling up of services in many countries. Most GHIs have focused on a single or a discreet range of diseases using vertical disease-control approaches, placing less emphasis on the strengthening of health systems needed to deliver these programs. However, given the scale of funding, there has been considerable debate and discussion about the role of GHIs in relation to health systems in LICs (Balabanova, Mckee et al 2010; Sridhar 2010, among others1). In 2009, a large international group under the auspices of the World Health Organisation (WHO), called the WHO Maximising Positive Synergies Collaborative Group (WHO MPSC Group), undertook a review of the interactions between GHIs and country health systems. The study found that GHIs and health systems are inherently linked, and have positive and negative impacts on each other (WHO MPSC Group 2009). Similarly, recent evaluations of GAVI and GFATM the key GHIs having specific health system funding programs highlighted that strengthening of national health systems was necessary to enhance the performance of the two initiatives (HLSP 2009; TERG 2009). Interestingly, these findings came to light around the same time that the world experienced a financial crisisa phenomenon that forced several donors to reconsider their funding commitments to global health. This has not only put pressure on the ability of GHIs to attract the funding to sustain current work, but has also raised questions on their effectiveness in achieving health goals. The reviews, coupled with the need for wise investments and improved efficiency, provide an important opportunity to reflect on the debates surrounding GHIs and their impact on efforts to strengthen health systems in LICs. These issues are particularly relevant to aid effectiveness reforms that have occurred since the mid-2000s. This paper provides an overview of the key issues, specifically in terms of shortcomings, around the interactions of GHI programs with health systems. This is done by first looking at the impacts on health financing and service delivery, followed by a review of GHIs approaches to health systems strengthening. The paper then highlights how aid effectiveness is also linked to GHIs programming and health systems strengthening efforts, and suggests that tensions inevitably arise as a result of the aims of the three processes. It concludes by arguing that these tensions need to be actively managed through closer dialogue between global, national and sub-national health practitioners. This paper is based on a selective review of the literature, so as to identify a range of viewpoints, rather than a comprehensive survey. It largely draws upon the evaluations of key GHIs, namely those of GAVI (HLSP 2009) and GFATM (TERG 2009), the study conducted by the WHO MPSC Group (2009) on interactions between GHI programs and health systems and related documents released around the same time that the reviews were undertaken. Some of the literature from these studies was subsequently peer-reviewed and published in scientific and academic journals. As the information base on GHIs and health systems is rapidly developing, here the focus was on literature produced between 2000 and 2010.

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

WORKING PAPER SERIES

CONCEPTS AND DEFINITIONS

Health Systems and Health System Strengthening

In accordance with WHO, we define health systems as all organizations, people and actions whose primary purpose is to promote, restore or maintain health (WHO 2000; WHO 2007). WHO further describes health systems as characterised by six main components: service delivery, a health workforce, information systems, medical products, vaccines and technologies, and financing, as well as leadership and governance (WHO 2007). This paper focuses on financing and service delivery when discussing the impacts of GHI programs on health systems, as these have been the areas that have received the most attention in reviews and debates about GHIs. This is not to say that other efforts in capacity building or improving access to drugs are not important, but rather to focus the analysis more clearly.2 Unlike health systems, health systems strengthening (HSS) is not consistently referred to with a standard definition. In this paper, the term is understood as a process, comprising various strategies and initiatives, aimed at enhancing the functioning of any or all of the components of health systems to achieve more equitable and sustained improvements across health services and health outcomes (WHO 2007). The policies and actions aimed at improving health outcomes for individuals and families in LICs can operate at different levels of health systems. Drawing on Hanson, Ranson et al (2003) description, we define the following levels of action and influence, which are delineated on the basis of the impact and nature of decision making: (1) household or individual health consumer level; (2) community levelnaturally forming clusters of households in a delineated local area; (3) health service delivery level, comprising networks of clinics, hospitals and other related services; (4) health sector level, which is responsible for local policy and oversight of service delivery, most often provincial or regional governance; (5) national levelthe sovereign state, and encompassing all the legal and regulatory responsibilities of the state related to health and well-being; (6) regional level, where neighbouring countries collectively discuss health policy, priority setting and joint action; and (7) global level of international and multilateral policy making and action. As this is an increasingly complex area, here we adopt a narrower focus by looking at the influence of actions related to GHIs globally and nationally.

Global Health Initiatives

Global Health Initiatives are diverse in nature, ranging from formal, legally incorporated entities to more informal groups variously called partnerships, alliances, international partnerships, councils and projects. Their members come from the various arms and agencies of national governments, the corporate sector, not-for-profit sector, academia, civil society and even individuals representing their own interests. GHI roles include: providing a range of services related to a specific disease or health issue, providing technical advice, advocacy, conducting research and coordinating and delivering prevention and treatment services. Others are solely financing mechanisms. There are now thought to be about 100 GHIs providing development assistance for health (DAH). Among the most prominent GHIs in terms of influence and financial resources are GAVI, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Box 1), GFATM, the US Presidents Emergency Plan for AIDs Relief and the World Banks Multi-Country AIDS Program. For a more comprehensive list, see the WHO MPSC Groups review (2009).

Those seeking a wider review are referred to the WHO MPSC Groups review (2009), which provides a comprehensive overview of the interactions between GHIs and health systems in relation to all six areas, based on literature published up to 2009.

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges 3

WORKING PAPER SERIES

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

While difficult to define, GHIs do have some common features. The WHO MPSC Group (2009) suggests that these include: a focus on specific diseases or on selected interventions, commodities or services; relevance to several countries; ability to generate substantial funding; inputs linked to performance; and direct investment in countries, including partnerships with non-government organisations and civil society. We would add the important feature of operating in this newly expanded policy space at the global level. For the purposes of this paper, we refer to GHIs as a new institutional layer in the health arena. The term global is a contentious one and is not always used consistently. While they exist at a global level, most GHIs aim to make health improvements at the national and sub-national level. Though there have been a range of international and multinational organisations operating at this level for more than a century, these newer institutions appear to operate in a manner quite different from those that already existed. Over a comparatively short time, GHIs have emerged, gained authority and voice and are giving this global level its own identity and character.

Box 1. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Development Assistance for Health

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation was created in early 2000. By 2006, with the addition of a major contribution from investor Warren Buffet, it has become the biggest philanthropic institution in the world, with a total endowment of an estimated US$60 billion.1 The Foundation has recently announced that it will increase the amount it will spend to about US$3 billion per year.2 Following a reorientation of the Foundation in 2006, global health has become one of three major areas of activity. Under its global health program, by far the largest grants have been made to GAVI, which will receive US$1.5 billion 1999-2015 for both the purchase of vaccines and general operating support. Other grantees receiving large amounts are: Program for Appropriate Technology in Health with US$825 million, Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria with US$650 million, World Health Organization with US$300 million and Medicines for Malaria Venture with US$200 million. The majority of funding is for research in the areas of HIV/AIDS, malaria, maternal and reproductive health, immunisation of children and other infectious diseases. The actual breakdown of funds allocated is very difficult to categorise from publicly available information because of the lack of detailed information on each grant and the differences in length of time of each grant. The Foundation has identified three interrelated programs: iscovery: closing gaps in knowledge and science and creating critical platform technologies in areas where current tools are D lacking. elivery: implementing and scaling up proven approaches by identifying and proactively addressing the obstacles that typically lie in D the path of adoption and uptake. olicy and advocacy: promoting more and better resources, effective policies, and greater visibility of global health so as to P effectively address the Foundations priority health targets. See: http://www.gatesfoundation.org/global-health/Pages/overview.aspx.

1 By comparison UK Welcome Foundation has endowment of US $19 billion and Ford Foundation has US $ 11 billion. 2 Economist January 6, 2009.

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

WORKING PAPER SERIES

GLOBAL HEALTH INITIATIVES AND HEALTH SYSTEMS

The Impact of GHI Programs on Health Systems

Most GHIs, such as GFATM, GAVI and the World Banks Multi-Country AIDS Program, are primarily financing instruments. These initiatives channel funds to countries for specific health programs with a goal, among others, of scaling cost-effective interventions to increase coverage and access. The sheer scale of funds provided, coupled with GHIs vertical program approach and emphasis on scaling up services, have generated considerable interest in the impact of GHI programs on already weak health systems in LICs. As early as 2001, when GHIs were starting to become more prominent in health development, it was envisaged that the initiatives would have important effects on health systems (Biesma, Brugha et al 2009). However, it is only over the past few years that the impacts of GHI programs have been better understood, due to evaluations of GHIs, systematic reviews of evidence and empirical studies conducted within countries. Some of the negative impacts on health systems highlighted across the literature include: (1) The lack of accountability of global donors to country governments (Sridhar 2010). (2) The emphasis on scaling up disease-specific interventions may increase the burden on an already overstretched human resource capacity by generating additional demand for health care (WHO MPSC Group 2009). (3) The focus on specific health areas distracts governments from other national priorities, including efforts to strengthen health systems (Biesma, Brugha et al 2009). (4) A variable degree of alignment with country planning processes and priorities: while many GHI programs are linked with country planning processes, they also result in the creation of additional planning structures within countries.3 The proliferation of funding sources and coordinating mechanisms increases administrative burdens and leads to fragmentation, thereby undermining harmonisation (Sridhar 2010; WHO MPSC Group 2009). In this section, we focus on how GHIs have impacted on two specific components of health systems: financing and service delivery. Reviews such as those carried out by the WHO MPSC Group (2009) and Biesma and colleagues (2009) provide a detailed overview of how GHI programs interact with health systems. Health financingglobal and national During the past decade, GHIs have played a significant part in the major increase in funds made available globally for Development Assistance for Health (DAH). While there are differing estimates of the overall increase in funds, it is clear that DAH has increased both as a proportion of overall foreign aid and as a proportion of world Gross National Income (GNI). The OECD (2009) reports that DAH increased from US$2.5 billion in 1990 (0.16% of GNI) to more than US$13 billion in 2005 (0.41% of GNI); health aid as a proportion of total overseas development assistance increased from 4.6% in 1990 to almost 13% in 2005. Total DAH has continued to increase despite the 2009 global financial crisis, reaching US$26.9 billion in 2010, a 50% increase on the US$17.8 billion in 2006 (IHME 2010). It is estimated that in 2010 GHIs provided approximately 20% of total DAH (up from about 15% in 2006); bilateral government assistance provided nearly 50% (up from 35% in 2006); and the proportion contributed by the United Nation (UN) system and other multilateral agencies (approximately 20% in 2010) and Non Government Organisations (NGOs) (5% in 2010) had both fallen. Increased funding from GHIs was responsible for about 50% of the increase in total DAH between 2006 and 2010 (authors estimates based on IHME data). It has also been reported that the GHIs tend to make longer term commitments for project funding than do the more traditional bilateral and multilateral aid agencies. Dodd and Lane (2010) found that GHIs accounted for five of the six longest commitment periods identified in their review. Due to the influence of GHIs, this increased DAH has been targeted at certain specific diseases and has markedly changed the manner in which control of these diseases is funded. For example, the WHO MPSC Group estimates that, in 2007, GHIs accounted for two-thirds of external funding for HIV/AIDS prevention and care, 57% for tuberculosis control and 60% for malaria control (2009).

3 Such as the GFATMs country coordinating mechanism and GAVIs interagency coordinating committee.

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges 5

WORKING PAPER SERIES

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

Whether or not the increased DAH substitutes for national health spending is a fraught issue, both public and private donors generally want to see their aid as increasing the total amount available for national spending on health. GFATM, for example, includes in its country agreements undertakings that its funds will not be used to reduce the overall level of national spending in the specific areas related to its initiatives.4 However, the WHO MPSC Group noted that there was inconclusive evidence on the impact of increased GHI funding on domestic government expenditure for health. While there was some evidence of reduced government expenditure on HIV in sub-Saharan African countries receiving GHI support, there was also evidence that GHIs have contributed to a reduction in user fees and out of pocket expenses, especially for those suffering from the targeted diseases (WHO MPSC Group 2009). Despite this increased funding, many in the aid sector question whether it is sufficient to do the job. In one recent initiative, a group of donor governments established the High Level Taskforce on Innovative International Financing for Health Systems, which attempted to estimate the total cost of meeting the targets set in the health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), based on the needs of the 49 poorest countries (Fryatt, Mills et al 2010). The task force investigated both the capital investments required and the ongoing operational funds needed to sustain the delivery of health services underpinning the MDG targets. The Taskforce estimated that while US$31 billion was currently spent on the health-related MDGs globally by national and international partners, a further US$36-45 billion per year is required. While the value of such a global estimate is somewhat limited, it does give an indication of the order of magnitude of the funding required. Moreover, as many commentators have observed, it is a relatively small amount compared with the costs of, for example, the bailing out of major banks during the global financial crisis. Health service delivery While the additional funding channelled by GHIs for specific diseases is an important development in global health, it is equally important to consider where the finances are being invested and the returns on these investments. In a review of the impact of GHIs on health service delivery, the WHO MPSC Group (2009) noted that one characteristic of GHIs was their focus on scaling up selected services that have proven to be effective. The impact of GHI funding on three areas was examined: access or coverage, equity and quality of services. The group found evidence of significant increases in coverage of key interventions for target diseases (AIDS, malaria, TB) and vaccination, although it was not always clear how much of the increase could be attributed to contributions from the GHIs. There was also evidence of both positive and negative effects on coverage of non-targeted services and conditions. When the disease-control programs that are funded by GHIs are seen alongside the reports on progress in meeting the health-related MDGs (see, for example, WHO 2010a), expansion in service delivery is apparent in many countries. However, in the case of HIV/AIDS, for example, the numbers of new infections continues to rise, and approximately 55% of those estimated to need treatment currently receive it. The WHO MPSC Group noted that the introduction of standardised protocols and measurement of adherence to these protocols have contributed to improved quality of service delivery (World Health Organization, Maximizing Positive Synergies Collaborative Group 2009). However, the emphasis on meeting numerical targets may have a negative impact both on equity (with efforts directed towards target populations in urban and easy to reach areas) and on service quality. The group raised questions about the extent to which the diseases or conditions targeted by GHIs aligned with the needs and priorities of recipient countries. They noted that while GHIs address issues of global importance based on global epidemiological evidence, precise assessment of need was not available for most LICs. Table 1 illustrates the issues discussed in this section within specific country contexts, based on literature published since 2009. From the evidence available, it is clear that GHI programs have both positive and negative impacts on health systems in LICs. While there has been fragmentation of systems, creation of parallel structures and distortion in resource allocation, governance and multi-stakeholder participation have also

4 Such as the GFATMs country coordinating mechanism and GAVIs interagency coordinating committee.

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

WORKING PAPER SERIES

improved in several countries. The relationship between GHI programs and health systems, however, is not one way. It has also been well acknowledged that health systems need to be strengthened in order to sustain scaling-up of services. A WHO report noted: [W]ithout more support to help countries build health system capacity, the resources mobilised by GHIs are unlikely to reach their full potential (WHO 2006). Next we turn to reviews of GHI approaches to strengthening health systems.

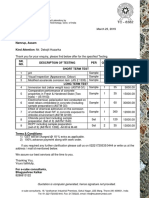

Table 1. Interactions between GHI Programs and National Health Systems

Study Area Global Fund in Nepal Findings related to health systems High disease control outcomes, especially for at-risk groups, and strengthened civil society partnerships. However, high levels of system fragmentation with creation of parallel monitoring and evaluation structures (Trgrd and Shrestha 2010). Significant improvements in disease control and improved civil society partnerships. On balance, there was not an overall benefit or negative impact on health systems development (Hanvoravongchai, Warakamin et al 2010). GFATM-supported activities were found to be coordinated with the National HIV and TB programs. However, parallel and vertical systems were established to meet the demands of program scale-up and the performance-based nature of GFATM investment (Rudge, Phuanakoonon et al 2010). High integration of GFATM investments into vertical programs, strengthening of stewardship and governance and little integration of monitoring and evaluation into the national health information system. Potential distortions in human resource allocation as staff shift into incentive-based positions of GHI-funded programs (Desai, Rudge et al 2010). Improved extension of health facilities and access to care for high-risk groups for TB and HIV. Good integration with national programs, with the exception of monitoring and evaluation. A positive impact on health systems development, although the distortion of resource allocation (communicable disease control in contrast to maternal and child health) is raised as a concern (Mounier-Jack, Rudge et al 2010). Although GAVI governance mechanisms demonstrated high levels of performance in relation to GAVI application processes, there were significant gaps in strategic gap analysis. Managing through systems, rather than being over-reliant on committees, will broaden participation in implementation and, in doing so, expand the reach of immunisation and maternal and child health care (Grundy 2010). Positive synergies between disease-specific interventions and non-targeted health services are more likely to occur in robust health services and systems. Disease-specific interventions implemented as parallel activities in fragile health services may further weaken their responsiveness to community needs, especially when several GHIs operate simultaneously (Cavalli, Bamba et al 2010). Evidence suggests that while GHIs have contributed significantly to enabling the rapid scaling up of anti-retroviral therapy in both countries, they may also have had a negative impact on coordination, the long-term sustainability of treatment programs and equity of treatment access (Hanefield 2010). Positive effects included the creation of opportunities for multi-sectoral participation, greater political commitment and increased transparency among most partners. However, the quality of participation was often limited, and some GHIs bypassed coordination mechanisms, especially sub-national ones, weakening their effectiveness (Spicer, Aleshkina et al 2010).

Global Fund in Thailand

Global Fund in Papua New Guinea (PNG)

Global Fund in Indonesia

Global Fund in Laos

GAVI: Governance in five Asian countries

Impact of GHIs in Mali

Impact of GHIs on services in Zambia and South Africa

Impact of GHIs on HIV/AIDs services in seven countries

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges 7

WORKING PAPER SERIES

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

The Approach of GHIs to Health System Strengthening

Since the beginning of their operation, many GHIs have recognised the need to strengthen health systems in order to maximise achieving health goals. The framework document of GFATM, for example, states that the organisation will support the substantial scaling up and increased coverage of proven and effective interventions, which strengthen systems for working: within the health sector; across government departments; and with communities (GFATM 2002). The document also says that GFATM will support programs that address the three diseases [AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria] in ways that will contribute to strengthening health systems (GFATM 2002). Since 2002 GFATM has been supporting health systems strengtheningeither as a part of specific disease programs or as a component that supports delivery of programs across AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria (Box 2). Similarly, GAVI has a specific funding stream for HSS. In 2004, the organisation commissioned a study on the barriers to increasing immunisation coverage. The study found that health system constraints outside of immunisation programs were limiting expansion in coverage or hindering sustainability of high immunisation rates (GAVI 2004). Health system barriers identified included insufficient resources going to health care, limited flexibility in use of resources, management inefficiencies and shortages in human resources for health (GAVI 2004). Under-investment over a number of years and a lack of will to address human resources issues seriously had caused a failure to establish effective systems for workforce planning, production and management, resulting in shortages, poor distribution and an inadequate skill mix (GAVI 2004). Thus, in December 2005, GAVIs Board approved the creation of a funding window for HSS related to delivery of immunisation (Box 2). Despite the efforts by GHIs to support weak health systems in LICs, it has been suggested that funded activities are falling short of producing wide positive impacts. This is largely attributed to the fact that, as Balabanova, Mckee et al (2010) point out, the HSS activities supported by GHIs involve support for a limited set of functions necessary for the delivery of their own activities or integration of their activities into the existing system. For example, as already mentioned, both GFATM and GAVI fund only those HSS activities related to their own areas of focus. For these reasons, Marchal, Cavalli et al (2009) argue that while many GHIs claim to fund HSS activities, these can actually be considered selective disease-specific interventions. Thus, the criticisms around the impacts of GHI programs on health systems continue to hold true.

Box 2. The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and Health System Strengthening

The GFATM has long recognised the key role health systems play in supporting progress towards its goals. The Global Funds major objectives in providing funding for HSS are to: (1) improve grant performance and (2) increase the overall impact of responses to the three diseases. GFATM recognises that supporting the development of equitable, efficient, sustainable, transparent and accountable health systems furthers achievement of these objectives. Currently, GFATM allows applicants to apply for funding to respond to health system weaknesses either through a program (by disease) approach, or by a cross-disease approach, recognising that the response may differ substantially in different settings. The organisation also accepts national health strategy applications provided that they have been properly validated and that civil society and the private sector have participated in the development of these strategies. See: Pearson 2008

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

WORKING PAPER SERIES

AID EFFECTIVENESS AND HEALTH SYSTEMS STRENGTHENING

Apart from the unique mechanisms adopted to mobilise and disburse funds, GHIs have also been recognised for their efforts in engaging various stakeholders (including people living with disease and for-profit actors) in decision making, raising the position of health on the development agenda and adapting to the new agendas that emerge as the global health architecture evolves. The latter characteristic is particularly pertinent to the issues raised in this paper. Of relevance to GHIs and health systems, particularly, is the aid effectiveness agenda of development partners.

What about Aid Effectiveness?

Over the past decade, health development has been characterised not only by the advent of GHIs but also by a reform movement regarding aid effectiveness. Donors have always been mindful of the need to sell the achievements of their aid programs domestically, but the increases in DAH have led to a rethinking. This is not surprising because increased funding usually goes hand in hand with greater scrutiny and oversight, but it is important to recognise that this agenda also builds on the growing evidence base of what works in development programming. The aid effectiveness agenda, captured in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (OECD 2005), and later in the Accra Agenda for Action (OECD 2008), aims to improve the delivery, management and use of development assistance (which includes DAH) in order to maximise the impact on development. In order to meet this goal, the agenda, which was agreed to by more than 100 development partners, centres on a number of principles that endeavour to change the nature of the relationships between donors and recipients and reform the way bilateral and multilateral aid is delivered and managed (Box 3).

Box 3. The Paris Declaration and the Accra Agenda

The five key principles of the 2005 Paris Declaration, which aims to strengthen aid governance and improve aid performance, are: Ownership: Developing countries set their own strategies for poverty reduction, improve their institutions and tackle corruption. Alignment: Donor countries align their aid programs with these objectives and use local systems. Harmonisation: Donor countries coordinate with each other, simplify procedures and share information to avoid duplication. Results: Developing countries and donors shift focus to development results, and results are measured. Mutual Accountability: Donors and partners are accountable for development results. The 2008 Accra Agenda introduced new elements to aid effectiveness: Predictability: Donors will provide three-to-five-year forward information on their planned aid to partner countries. Country systems: Partner country systems will be used to deliver aid as the first option, rather than donor systems. onditionality: Donors will switch from reliance on prescriptive conditions about how and when aid money is spent to conditions C based on the developing countrys own development objectives. ntying aid: Donors will relax restrictions that prevent developing countries from buying the goods and services they need from U whomever and wherever they can get the best quality at the lowest price. See: OECD 2005; OECD 2008

As a consequence, several recommendations have been put to GHIs to address the issues raised in the Paris Declaration and the Accra Agenda. These have focused on the engagement of GHIs with country systems and on the operation of GHIs themselves. The recommendations include: (1) Funding mechanisms: Adapt to using a mix of longer term and programmatic funding to support scaling up. dopt a more targeted, results-focused or challenge-based funding approach where innovation and piloting A are required. eek to provide country allocation estimates based on agreed criteria of need, to improve predictability and S equity of distribution (Isenman, Wathne et al 2010).

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011 Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges 9

WORKING PAPER SERIES

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

(2) Aid alignment: HI programs should be better aligned with national country strategies and plans (Biesma, Brugha et al G 2009; WHO MPSC Group 2009). ecipient countries should develop coherent national strategies with which GHIs can align (Balabanova, R Mckee et al 2010). Improve coordination of donor investments to support national strategic plans (Biesma, Brugha et al 2009) (3) Donor harmonisation and coordination: Recipient countries should be allowed more flexibility in using GHI resources (Biesma, Brugha et al 2009). Support the ongoing engagement of non-state and civil society stakeholders (Biesma, Brugha et al 2009). adically simplify the global health architecture and reduce transaction costs (Balabanova, Mckee et al 2010). R (4) Health system weaknesses: HIs should more comprehensively address health system weaknesses and assist countries to address G public sector health worker shortages through long-term funding (Biesma, Brugha et al 2009). ountries and GHIs should identify and address complex, more fundamental health system needs (WHO C MPSC Group 2009). Ensure integration of programs in service delivery (Balabanova, Mckee et al 2010). (5) Improved evidence for health system interventions, and indicators for measuring health system changes: dentify indicators and targets for health system changes to enable performance measurement and provide I more evidence on health system investments and their costs and benefits (WHO MPSC Group 2009; Balabanova, Mckee et al 2010). (6) Capacity building: upport recipient countries to develop a coherent national strategy for prioritising external support and S managing it together with local resources in a coordinated way (Balabanova, Mckee et al 2010). ive more attention to capacity development of country partners, particularly in terms of longer term and G sector-wide assessment and planning (Isenman et al 2010). GHIs and the global health community have attempted to address many of the problems. Looking at the HIV/AIDS-focused GHIs over 2002-07, Biesma, Brugha et al (2009) documented improvements, particularly in alignment with national joint strategies, support for national monitoring and evaluation systems and increased training and improved working conditions for health workers. However, they noted less progress in harmonisation at country level, as illustrated by the creation of multiple country coordination mechanisms in addition to parallel GHI-specific administration and reporting structures. Globally, a range of coordinating structures and mechanisms has been developed, including agreements such as the Best Practice Principles for country engagement of global health partnerships, as well as new mechanisms like the International Health Partnership (IHP+, see Box 4) and the proposed common financial platform for World Bank, GAVI and GFATM (Balabanova, Mckee et al 2010; WHO 2006).

10

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

WORKING PAPER SERIES

Box 4. What is the International Health Partnership?

The International Health Partnership, or IHP+, was launched in 2007 to promote the principles of the Paris Declaration and the Accra Agenda. It is open to all developing and developed country governments, agencies and civil society organisations involved in improving health who are willing to sign up to the commitments of the IHP+ Global Compact. It currently has 47 members. In addition to the Global Compact, development partners also made a number of agency-specific commitments, as outlined below. Partner Commitments: mprove how they work to implement the agreements in country compacts and to expand the partnership to other countries and I partners. Establish a joint process for in-country assessment of national health and HIV/AIDS plans and strategies. ccelerate progress by development partners on realising the behaviour changes set out in global and country compacts and in A accordance with commitments made in the Paris Declaration and the Accra Agenda. Establish a robust framework for mutual accountability. Support civil society engagement at all levels. Harmonise procurement policies. GHI commitments: The GAVI Board committed to support IHP+ in October 2008. he GFTAM committed to designing a new financing architecture based on disease-specific national plans to simplify grant T management and processes and align with countries for implementation in 2010; it will monitor all grants for consistency with Paris Principles. GAVI and GFATM will jointly explore opportunities for common programming and funding support for HSS. United Nations commitments: he United Nations International Childrens Emergency Fund, United Nations Family Planning Association, United Nations T Development Program, World Health Organization and the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS each agree to work closely through the UN resident coordinator to align their process in IHP+ countries. The World Bank will continue to provide technical support through existing programs. See Ministerial Review Communiqu, 5 February 2009 at: http://www.internationalhealthpartnership.net/CMS_files/documents/ ministerial_review_meeting_commu_EN.pdf (accessed 15 December 2010).

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges 11

WORKING PAPER SERIES

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

Is the HSS Platform Better Aligned with Aid Effectiveness?

A practical response by the GHIs and international agencies to the challenges of implementation presented by the Paris Declaration and the Accra Agenda has been the HSS Platform. This was established in 2009 as a joint arrangement between the World Bank, GAVI, GFATM and WHO. It was introduced as a mechanism to coordinate, mobilise, streamline and channel the flow of existing and new international resources to support national health strategies (World Bank 2010). The focus of the HSS Platform is to increase investment in national health system strengthening strategies in accordance with the principles of aid effectiveness. The platform will also undertake joint assessment of national health plans and increase investments in national health planning (World Bank 2010). The rationale for introducing a health systems platform is based also on the need to devise a more rational distribution of health care resources. The plan to mobilise more resources for health systems development is a response to the fact that more than half of all DAH goes to control of communicable diseases, with little by comparison for basic health service delivery (England 2009). The aid effectiveness agenda and health system platform approaches have also been catalysts for moves towards development of a Global Strategy for Maternal and Child Health, with likely priority areas including results-based financing, new technologies and public-private partnerships (Ban 2010). The emergence of the HSS Platform and the Global Strategy for Maternal and Child Health indicates that the current trend towards development of GHIs is being accelerated by the need for more effective aid management and delivery over more predictable and longer time frames.

It is interesting that multilateral efforts in maternal and child health arising from the review of the MDGs in 2010 include the development of the OneHealth Model; see www.internationalhealthpartnership.net/en/working_groups/working_group_on_costing.

12

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

WORKING PAPER SERIES

CONCLUSIONS

Since the turn of the new millennium, GHIs have quickly emerged as an important player, altering the health development landscape in a variety of ways. GHIs have established new forms of governance, pioneered new mechanisms by which to raise and disburse funds and brought new energy and enthusiasm to achieving development goals. In countries, the initiatives have sought to promote accountability, transparency and multi-stakeholder participation, in addition to supporting dramatic scaling up of cost-effective interventions for particular health programs. The financial resources available and vertical programming approach of GHIs has generated considerable debates around the effects of GHI programs on national health systems. These discussions are particularly relevant now, a time characterised by calls for more health for money. This paper sought to highlight the key issues surrounding GHIs and health systems, in terms of impact and approaches to HSS. Evidence from around the world suggests that GHI programs and health systems interact in several waysboth positive and negative. We found that GHIs have been criticised for largely promoting a focus on downstream service delivery and quick solutions in tackling certain prominent disease areas without adequately addressing underlying constraints in health service delivery. The concern most often raised is the fragmentation and complexity the GHIs have added to aid funding. At the same time, the global initiatives have also acknowledged, since the early days of their operation, the need to address their grantees weak health systems, but have taken some time to do sofor example through specific HSS funding channels. Their persistent use of vertical disease-control interventions and approaches continues to be the cause of much of the criticism of GHIs, particularly for those trying to strengthen health systems in LICs. Many of the criticisms around the impact of GHI programs on health systems are at the heart of the aid effectiveness agenda, namely those related to country ownership, alignment with country systems and harmonisation between donors. Isenman and colleagues (2010), as well as WHO (2010b) cite this as a particular problem for highly aid-dependent countries, though less of an issue for countries where aid is a relatively small proportion of total health financing. In light of this, most commentators have emphasised the need for greater alignment between GHI operations and the principles of aid effectiveness. A variety of recommendations are currently being implemented by GHIs and development partners in the form of a common HSS funding platform. At the end of 2010, preparatory work to implement the platform in a select number of countries was being undertaken.5 It is thus apparent that while GHIs programming approaches, HSS and aid effectiveness largely overlap, there is a gap between policy and practice. The gap between what is said and what is done creates a tension between what is occurring at the global level and in countries. We argue that these are tensions which need to be recognised and managed by those working in health and development globally, nationally or sub-nationally. GHIs ability to mobilise funds and stimulate rapid scaling up of services for particular diseases has proven to be important to particular health goals. However, this phenomenon still needs to be balanced with HSS, which is required in order to promote, maintain and restore health equitably and sustainably. Greater attention to the complex task of making the aid effectiveness agenda more of a reality requires changes in the way various actors work, both globally and in countries. Managing the tension will require close cooperation between health system practitioners working globally and nationally. At the global level, there is a temptation to see similarities across countries and look for onesize-fits-all solutions. There is also a tendency to introduce additional global coordination mechanisms and structures, though what may be needed is more attention to country coordination. Country planners seem often to highlight differences and find difficulty in identifying economies of scale. The truth may well be somewhere in between, but it will not be found unless there is dialogue and exchange of information. The tendency of the GHIs to hold themselves up for regular review and evaluation is a welcome advance. Without this, we would not have the basis of this discussion. However, we would argue that strengthening health systems in LICs provides a better focus for driving the continued investment in health development. It should be put more at the centre of the dialogue and knowledge exchange between global and national actors. This can only contribute to strengthening the health systems of LICs.

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges 13

WORKING PAPER SERIES

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

REFERENCES

Balabanova, D., M. Mckee, A. Mills, G. Walt and A. Haines. 2010. What can global health institutions do to help strengthen health systems in low income countries? Health Research Policy and Systems 8, 22. Ban Ki-moon. 2010. Global Strategy for Womens and Childrens Health. http://www.un.org/sg/hf/Global_ StategyEN.pdf, accessed 12 May 2011. Biesma, R.G., R. Brugha, A. Harmer, A. Walsh, N. Spicer and G. Walt. 2009. The effects of global health initiatives on country health systems: a review of the evidence from HIV/AIDS control. Health Policy and Planning 24, 4: 239-252. Cavalli, A., S.I. Bamba, M.N. Traore, M. Boelaert, Y. Coulibaly, K. Polman, M. Pirard and M. Van Dormael. 2010. Interactions between global health initiatives and country health systems: the case of a neglected tropical diseases control program in Mali. PLoS Neglected Tropical Disease 4, 8: e798. Desai, M., J.W. Rudge, W. Adisasmito, S. Mounier-Jack and R. Coker. 2010. Critical interactions between Global Fund-supported programmes and health systems: a case study in Indonesia. Health Policy and Planning 25, Supplement 1: i43-47. Dodd, R. and C. Lane. 2010. Improving the long term sustainability of health aid: are Global Health Partnerships leading the way? Health Policy and Planning 25, 5: 363-371. England, R. 2009. The GAVI, Global Fund, and World Bank joint funding platform. Lancet 374, 9701: 1595-6. Fryatt, R., A. Mills and A. Nordsrom. 2010. Financing of health systems to achieve the health Millennium Development Goals in low income countries. Lancet 375, 9712: 419-26. Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI). 2004. Alleviating System Wide Barriers to Immunization: Issues and Conclusions from the Second GAVI Consultation with Country Representatives and Global Partners. http://www.gavialliance.org/resources/system_wide_barriers_NORAD_study.pdf, accessed 5 May 2011. Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM). 2002. The framework document of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/TGF_framework.pdf, accessed 10 May 2011. Grundy, J. 2010. Country-level governance of global health initiatives: an evaluation of immunization coordination mechanisms in five countries of Asia. Health Policy and Planning 25(3):186-196; doi:10.1093/ heapol/czp047. Hanefeld, J. 2010. The impact of Global Health Initiatives at national and sub-national levela policy analysis of their role in implementation processes of antiretroviral treatment (ART) roll-out in Zambia and South Africa. AIDS Care 22, Supplement 1: 93-102. Hanson, K., K. Ranson, V. Oliveira-Cruz and A. Mills. 2003. Expanding access to health interventions: a framework for understanding the constraints of scaling-up. Journal of International Development 15, 1-14. Hanvoravongchai, P., B. Warakamin and R. Coker. 2010. Critical interactions between Global Fund-supported programmes and health systems: a case study in Thailand. Health Policy and Planning 25, Supplement 1: i53-57.

14

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

WORKING PAPER SERIES

HLSP, Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation. 2009. Health System Strengthening Support Evaluation 2009 Volume 1: Key Findings and Recommendations. London: HLSP. http://www.gavialliance.org/resources/ Volume_1_Key_FindingsRecs_GAVI_HSS_Evaluation_FINAL_Report_8th_October_2009.pdf , accessed 5 May 2011. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). 2010. Financing Global Health 2010: Development Assistance and Country Spending in Economic Uncertainty. Seattle: IHME. http://www.healthmetricsandevaluation.org/ sites/default/files/policy_report/2010/financing_global_health_report_FullReport_IHME_1110.pdf, accessed 5 May 2011. Isenman P, Wathne C and Baudienville G. (2010) Global Funds: Allocation Strategies and Aid Effectiveness. Final Report (July 2010). Overseas Development Institute. http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/download/4947.pdf accessed 4 August 2010 Marchal, B., A. Cavalli and G. Kegels. 2009. Global Health Actors Claim To Support Health System StrengtheningIs This Reality or Rhetoric? PLoS Med 6, 4: e1000059. Mounier-Jack, S., J.W. Rudge, R. Phetsouvanh, C. Chanthapadith and R. Coker. 2010. Critical interactions between Global Fund-supported programmes and health systems: a case study in Lao Peoples Democratic Republic. Health Policy and Planning 25, Supplement 1: i37-42. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2005. Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/30/63/43911948.pdf, accessed 5 May 2011. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2008. Accra Agenda for Action. http://www. oecd.org/dataoecd/30/63/43911948.pdf, accessed 5 May 2011. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2009. Development Cooperation Report 2009. Paris: OECD Publishing. http://www.oecd.org/document/44/0,3746, en_21571361_44315115_42202348_1_1_1_1,00.html, accessed 5 May 2011. Pearson, M. 2008. IHP+: Expanding predictable finance for health systems strengthening and delivering results. Background paper. HLSP and IHP+. http://www.internationalhealthpartnership.net/pdf/TF_Final%20Report%20 Background%20Paper%20Oct%2023.pdf, accessed 5 May 2011. Rudge, J.W., S. Phuanakoonon, K.H. Nema, S. Mounier-Jack and R. Coker. 2010. Critical interactions between Global Fund-supported programmes and health systems: a case study in Papua New Guinea. Health Policy and Planning 25, Supplement 1: i48-52. Spicer, N., J. Aleshkina, R. Biesma et al. 2010. National and sub national HIV/AIDS coordination: are global health initiatives closing the gap between intent and practice? Globalization and Health 6, 3. Sridhar, D. 2010. Seven challenges in international development assistance for health and ways forward. Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics 38, 3: 459-469. Technical Evaluation Reference Group (TERG). 2009. Synthesis Report of the Five year evaluation of the Global Fund. Geneva: Global Fund to Fight AIDs, Tuberculosis and Malaria. http://www.theglobalfund.org/documents/ terg/TERG_Summary_Paper_on_Synthesis_Report.pdf, accessed 28 November 2010. Trgrd, A. and I.B. Shrestha. 2010. System-wide effects of Global Fund investments in Nepal. Health Policy and Planning 25, Supplement 1: i58-62.

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges 15

WORKING PAPER SERIES

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

World Bank. 2010. Health Systems Funding Platform. http://go.worldbank.org/0D4C6GPQU0, accessed 5 May 2011) World Health Organization (WHO). 2000. The world health report 2000: health systems: improving performance. Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/whr00_en.pdf, accessed 9 May 2011. World Health Organization (WHO). 2006. Opportunities for global health initiatives in the health system agenda. Making health systems work: Working paper No. 4. Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/management/ Making%20HSWork%204.pdf, accessed 5 May 2011. World Health Organization (WHO). 2007. Everybodys business: Strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes. WHOs framework for action. Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_ business.pdf, accessed 5 May 2011. World Health Organization (WHO). 2010a. Monitoring of the achievement of the health-related Millennium Development Goals. Report to the Sixty-third World Health Assembly 2010. Geneva: WHO. http://apps.who.int/ gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA63/A63_7-en.pdf, accessed 5 May 2011. World Health Organization (WHO). 2010b. The World Health Report 2010. Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: WHO. http://www.who.int/whr/2010/en/index.html, accessed 5 May 2011. World Health Organization, Maximizing Positive Synergies Collaborative Group. 2009. An assessment of interactions between global health initiatives and country health systems. Lancet 373, 9681: 2137-2169.

16

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

HEALTH POLICY AND HEALTH FINANCE KNOWLEDGE HUB

WORKING PAPER SERIES

NUMBER 11 | SEPTEMBER 2011

Global health initiatives and health systems: a commentary on current debates and future challenges

KNOWLEDGE HUBS FOR HEALTH

Strengthening health systems through evidence in Asia and the Pacific

A strategic partnerships initiative funded by the Australian Agency for International Development

The Nossal Institute for Global Health

Вам также может понравиться

- Health-Seeking Behaviour Studies: A Literature Review of Study Design and Methods With A Focus On Cambodia (WP7)Документ17 страницHealth-Seeking Behaviour Studies: A Literature Review of Study Design and Methods With A Focus On Cambodia (WP7)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Governance and Stewardship in Mixed Health Systems in Low - and Middle-Income Countries (WP24)Документ18 страницGovernance and Stewardship in Mixed Health Systems in Low - and Middle-Income Countries (WP24)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Governance and Stewardship in Mixed Health Systems in Low - and Middle-Income Countries (WP24)Документ18 страницGovernance and Stewardship in Mixed Health Systems in Low - and Middle-Income Countries (WP24)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Telemedicine in IndiaДокумент8 страницAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Telemedicine in IndiaIJRASETPublicationsОценок пока нет

- Non-Communicable Diseases and Health Systems Reform in Low and Middle-Income Countries (WP13)Документ24 страницыNon-Communicable Diseases and Health Systems Reform in Low and Middle-Income Countries (WP13)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Non-Communicable Diseases and Health Systems Reform in Low and Middle-Income Countries (WP13)Документ24 страницыNon-Communicable Diseases and Health Systems Reform in Low and Middle-Income Countries (WP13)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Thesis Proposal HealthliteracyДокумент27 страницThesis Proposal HealthliteracyChristine Rodriguez-GuerreroОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Health FinancingДокумент101 страницаIntroduction To Health FinancingArianne A ZamoraОценок пока нет

- Summary of Purposes and ObjectivesДокумент19 страницSummary of Purposes and Objectivesrodolfo opido100% (1)

- Multi-Wing Engineering GuideДокумент7 страницMulti-Wing Engineering Guidea_salehiОценок пока нет

- Bedwetting TCMДокумент5 страницBedwetting TCMRichonyouОценок пока нет

- NORSOK M-630 Edition 6 Draft For HearingДокумент146 страницNORSOK M-630 Edition 6 Draft For Hearingcaod1712100% (1)

- Universal Health Care Act: Department of Health - Center For Health Development CalabarzonДокумент44 страницыUniversal Health Care Act: Department of Health - Center For Health Development CalabarzonPEÑAFLOR, Shealtiel Joy G.Оценок пока нет

- Q1. (A) The Diagram Shows A Microphone Being Used To Detect The Output From AДокумент10 страницQ1. (A) The Diagram Shows A Microphone Being Used To Detect The Output From ASivmi MalishaОценок пока нет

- Communicable and Noncommunicable Diseases PDFДокумент2 страницыCommunicable and Noncommunicable Diseases PDFAngela50% (2)

- Chemical Engineering Projects List For Final YearДокумент2 страницыChemical Engineering Projects List For Final YearRajnikant Tiwari67% (6)

- Regulating The Quality of Health Care: Lessons From Hospital Accreditation in Australia and IndonesiaДокумент22 страницыRegulating The Quality of Health Care: Lessons From Hospital Accreditation in Australia and IndonesiaNossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Plan Budget Healthcare PDFДокумент299 страницPlan Budget Healthcare PDFAboubacar Sompare100% (1)

- Bhert - EoДокумент2 страницыBhert - EoRose Mae LambanecioОценок пока нет

- Economics of Health CareДокумент17 страницEconomics of Health CareJason Young0% (1)

- Ethical - Legal and Social Issues in Medical InformaticsДокумент321 страницаEthical - Legal and Social Issues in Medical InformaticsHeriberto Aguirre MenesesОценок пока нет

- Jeremy A. Greene-Prescribing by Numbers - Drugs and The Definition of Disease-The Johns Hopkins University Press (2006) PDFДокумент337 страницJeremy A. Greene-Prescribing by Numbers - Drugs and The Definition of Disease-The Johns Hopkins University Press (2006) PDFBruno de CastroОценок пока нет

- Global HealthДокумент2 страницыGlobal HealthDon RicaforteОценок пока нет

- Health Care FinancingДокумент25 страницHealth Care FinancingOgedengbe AdedejiОценок пока нет

- 42 Global Occupational Health FINALДокумент54 страницы42 Global Occupational Health FINALIsep Wahyudin100% (2)

- Healthcare Delivery Through Telemedicine During The COVID 19 Pandemic - Full PaperДокумент11 страницHealthcare Delivery Through Telemedicine During The COVID 19 Pandemic - Full PaperShreyas Suresh RaoОценок пока нет

- health care system of swedenبДокумент34 страницыhealth care system of swedenبAhmedAljebouli0% (1)

- SHA301 Health Economics and Health FinancingДокумент3 страницыSHA301 Health Economics and Health FinancingThomas MaseseОценок пока нет

- Impacts and Socio-Economic Implications of COVID-19 in Bangladesh and Role of The Social Determinants of HealthДокумент12 страницImpacts and Socio-Economic Implications of COVID-19 in Bangladesh and Role of The Social Determinants of HealthManir Hosen100% (1)

- Boore, CarolineДокумент287 страницBoore, CarolineAmarshanaОценок пока нет

- Lung Center IntroductionДокумент6 страницLung Center IntroductionJer EmyОценок пока нет

- Patterns in Maternal Mortality Following The Implementation of A Free Maternal Health Care Policy in Kenyan Public Health FacilitiesДокумент12 страницPatterns in Maternal Mortality Following The Implementation of A Free Maternal Health Care Policy in Kenyan Public Health FacilitiesCosmas MugambiОценок пока нет

- LN Occ Health Safety Final PDFДокумент249 страницLN Occ Health Safety Final PDFDeng Manyuon Sr.Оценок пока нет

- Innovation Management: Final ExamДокумент4 страницыInnovation Management: Final ExamNicole Paula Gamboa100% (1)

- Primary Goal of Health Care System in The PhilippinesДокумент1 страницаPrimary Goal of Health Care System in The PhilippinesKrissia BaasisОценок пока нет

- Sivasankar Karunagaran PGXPM 152sik: Whistleblowing & The Environment: The Case of Avco EnvironmentalДокумент5 страницSivasankar Karunagaran PGXPM 152sik: Whistleblowing & The Environment: The Case of Avco EnvironmentalPraveen JaganathanОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Coping Strategies On Psychological Wellbeing Among Students of Federal University Lafia Nigeria 2161 0487 1000349Документ6 страницThe Impact of Coping Strategies On Psychological Wellbeing Among Students of Federal University Lafia Nigeria 2161 0487 1000349Liane ShamidoОценок пока нет

- Communicable DiseasesДокумент28 страницCommunicable DiseasesJulius Memeg PanayoОценок пока нет

- An Assestment of The Trinidad and Tobago Health Care SystemДокумент4 страницыAn Assestment of The Trinidad and Tobago Health Care SystemMarli MoiseОценок пока нет

- Coronavirus Disease 2019: An Essay Presented To The Faculty of Sibonga National High SchoolДокумент6 страницCoronavirus Disease 2019: An Essay Presented To The Faculty of Sibonga National High SchoolChristine Joy Sulib100% (1)

- Chapter 1-5Документ76 страницChapter 1-5niaОценок пока нет

- Electronic and Manual Record KeepingДокумент3 страницыElectronic and Manual Record KeepingSola Adetutu50% (2)

- Patricia BennerДокумент7 страницPatricia BennerGemgem AcostaОценок пока нет

- Ethical Issues in I.TДокумент13 страницEthical Issues in I.TMohamad ShafeeqОценок пока нет

- Management of Epileptic Patient in An Orthodontic ClinicДокумент7 страницManagement of Epileptic Patient in An Orthodontic ClinicVineeth VTОценок пока нет

- Trade and Services in Nepal: Opportunities and Challenges: Executive SummaryДокумент4 страницыTrade and Services in Nepal: Opportunities and Challenges: Executive SummaryNeel GuptaОценок пока нет

- How To Survive The Quarantine EssayДокумент3 страницыHow To Survive The Quarantine Essayapi-486514294100% (1)

- Health Informatics in The PhilippinesДокумент2 страницыHealth Informatics in The Philippineswheathering withyouОценок пока нет

- Community Health Nursing: An Overview: By: Arturo G. Garcia Jr. RN, MSN, US RNДокумент8 страницCommunity Health Nursing: An Overview: By: Arturo G. Garcia Jr. RN, MSN, US RNKristel AnneОценок пока нет

- Medical Education in The PhilippinesДокумент4 страницыMedical Education in The PhilippinesKaly RieОценок пока нет

- Webinar Reaction PaperДокумент1 страницаWebinar Reaction PaperJay VillasotoОценок пока нет

- Millennium Development Goals 3RD QДокумент19 страницMillennium Development Goals 3RD QSodaОценок пока нет

- Philippine's Healthcare System During The PandemicДокумент1 страницаPhilippine's Healthcare System During The PandemicMaria Erica Jan MirandaОценок пока нет

- OSH in PhilippinesДокумент27 страницOSH in PhilippinesTOt's VinОценок пока нет

- Global Burden of Disease GBD Study 2017 18 PDFДокумент70 страницGlobal Burden of Disease GBD Study 2017 18 PDFtutagОценок пока нет

- Mental Health in Health ProfessionalsДокумент23 страницыMental Health in Health ProfessionalsLUIS EDUARDO MEDINA MUÑANTEОценок пока нет

- Campaign Report Oral Health and SanitationДокумент2 страницыCampaign Report Oral Health and SanitationJulia AbdullahОценок пока нет

- Outsourcing Laboratory ServiceДокумент1 страницаOutsourcing Laboratory ServicejulietОценок пока нет

- Reflection Essay 1Документ3 страницыReflection Essay 1api-539262721Оценок пока нет

- Adam King - Nurs420 Final Essay - Overworking Nurses Decreases Patient SafetyДокумент20 страницAdam King - Nurs420 Final Essay - Overworking Nurses Decreases Patient Safetyapi-384488430Оценок пока нет

- Ethics - Health Care in The PhilippinesДокумент2 страницыEthics - Health Care in The PhilippinesRalphjoseph TuazonОценок пока нет

- Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Bedside Nursing Staff PDFДокумент4 страницыKnowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Bedside Nursing Staff PDFwindysandy100% (1)

- 7c0a PDFДокумент17 страниц7c0a PDFAngelica RojasОценок пока нет

- Health System Preparedness For Responding To The Growing Burden of Non-Communicable Disease - A Case Study of Bangladesh (WP25)Документ30 страницHealth System Preparedness For Responding To The Growing Burden of Non-Communicable Disease - A Case Study of Bangladesh (WP25)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Scientometric Trends and Knowledge Maps of Global Health Systems ResearchДокумент20 страницScientometric Trends and Knowledge Maps of Global Health Systems ResearchMalecccОценок пока нет

- Neoliberaslismo en APS AustraliaДокумент10 страницNeoliberaslismo en APS AustraliaJM LОценок пока нет

- AsiaEuropeJournal LAMYPHUAДокумент20 страницAsiaEuropeJournal LAMYPHUARISMA AZIZAHОценок пока нет

- Healthpolicyachievementsandchallenges South Asian SurveyДокумент27 страницHealthpolicyachievementsandchallenges South Asian SurveyWaliullah RehmanОценок пока нет

- Ibrahim Halliru T-PДокумент23 страницыIbrahim Halliru T-PUsman Ahmad TijjaniОценок пока нет

- Healthpolicyachievementsandchallenges South Asian SurveyДокумент27 страницHealthpolicyachievementsandchallenges South Asian SurveyRahman Md.MoshiurОценок пока нет

- Zayyana Musa T-PДокумент34 страницыZayyana Musa T-PUsman Ahmad TijjaniОценок пока нет

- Examining The Degree and Dynamics of Policy Influence: A Case Study of The Policy Outcomes From Hub-Funded Research Into Not-For-Profit Hospitals in IndonesiaДокумент32 страницыExamining The Degree and Dynamics of Policy Influence: A Case Study of The Policy Outcomes From Hub-Funded Research Into Not-For-Profit Hospitals in IndonesiaNossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Case Studies of Policy Influence For The Knowledge Hubs For Health Initiative: Design and Analytic Framework (WP23)Документ20 страницCase Studies of Policy Influence For The Knowledge Hubs For Health Initiative: Design and Analytic Framework (WP23)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Sustainable Health Financing in The Pacific (WP22)Документ14 страницSustainable Health Financing in The Pacific (WP22)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Private-Sector Provision of Health Care in The Asia-Pacific Region: A Background Briefing On Current Issues and Policy ResponsesДокумент18 страницPrivate-Sector Provision of Health Care in The Asia-Pacific Region: A Background Briefing On Current Issues and Policy ResponsesNossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Non-Communicable Diseases: An Update and Implications For Policy in Low - and Middle-Income CountriesДокумент12 страницNon-Communicable Diseases: An Update and Implications For Policy in Low - and Middle-Income CountriesNossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Mapping The Regulatory Architecture For Health Care Delivery in Mixed Health Systems in Low - and Middle-Income CountriesДокумент32 страницыMapping The Regulatory Architecture For Health Care Delivery in Mixed Health Systems in Low - and Middle-Income CountriesNossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Institutional and Operational Barriers To Strengthening Universal Coverage in The Lao PDR: Barriers and Policy Options (WP19)Документ22 страницыInstitutional and Operational Barriers To Strengthening Universal Coverage in The Lao PDR: Barriers and Policy Options (WP19)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Barriers To and Facilitators of Health Services For People With Disabilities in Cambodia (WP20)Документ16 страницBarriers To and Facilitators of Health Services For People With Disabilities in Cambodia (WP20)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Development Assistance in Health - How Much, Where Does It Go and What More Do Health Planners Need To Know? (WP21)Документ14 страницDevelopment Assistance in Health - How Much, Where Does It Go and What More Do Health Planners Need To Know? (WP21)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Health System Preparedness For Responding To The Growing Burden of Non-Communicable Disease - A Case Study of Bangladesh (WP25)Документ30 страницHealth System Preparedness For Responding To The Growing Burden of Non-Communicable Disease - A Case Study of Bangladesh (WP25)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- The Growth of Non-State Hospitals in Indonesia and Vietnam: Market Reforms and Mixed Commercialised Health Systems (WP17)Документ20 страницThe Growth of Non-State Hospitals in Indonesia and Vietnam: Market Reforms and Mixed Commercialised Health Systems (WP17)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Institutional and Operational Barriers To Strengthening Universal Coverage in Cambodia (WP18)Документ22 страницыInstitutional and Operational Barriers To Strengthening Universal Coverage in Cambodia (WP18)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- The Growth of Non-State Hospitals in Indonesia: Implications For Policy and Regulatory Options (WP12)Документ20 страницThe Growth of Non-State Hospitals in Indonesia: Implications For Policy and Regulatory Options (WP12)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Governance and Management Arrangements For Health Sector-Wide Approaches (SWAps) (WP8)Документ16 страницGovernance and Management Arrangements For Health Sector-Wide Approaches (SWAps) (WP8)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Strengthening Church and Government Partnerships For Primary Health Care Delivery in Papua New Guinea (WP16)Документ28 страницStrengthening Church and Government Partnerships For Primary Health Care Delivery in Papua New Guinea (WP16)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- A Comprehensive Review of The Literature On Health Equity Funds in Cambodia 2001-2010 and Annotated Bibliography (WP9)Документ80 страницA Comprehensive Review of The Literature On Health Equity Funds in Cambodia 2001-2010 and Annotated Bibliography (WP9)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Analysing Relationship Between The State and Non-State Health Care Providers, With Special Reference To Asia and The Pacific (WP10)Документ24 страницыAnalysing Relationship Between The State and Non-State Health Care Providers, With Special Reference To Asia and The Pacific (WP10)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Strengthening Church and Government Partnerships For Primary Health Care Delivery in Papua New Guinea (WP16)Документ28 страницStrengthening Church and Government Partnerships For Primary Health Care Delivery in Papua New Guinea (WP16)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- The Growth of Non-State Hospitals in Vietnam (WP15)Документ20 страницThe Growth of Non-State Hospitals in Vietnam (WP15)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Institutional and Operational Barriers To Strengthening Universal Coverage in Cambodia (WP18)Документ22 страницыInstitutional and Operational Barriers To Strengthening Universal Coverage in Cambodia (WP18)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Barriers To and Facilitators of Health Services For People With Disabilities in Cambodia (WP20)Документ16 страницBarriers To and Facilitators of Health Services For People With Disabilities in Cambodia (WP20)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- The Growth of Non-State Hospitals in Indonesia and Vietnam: Market Reforms and Mixed Commercialised Health Systems (WP17)Документ20 страницThe Growth of Non-State Hospitals in Indonesia and Vietnam: Market Reforms and Mixed Commercialised Health Systems (WP17)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Institutional and Operational Barriers To Strengthening Universal Coverage in The Lao PDR: Barriers and Policy Options (WP19)Документ22 страницыInstitutional and Operational Barriers To Strengthening Universal Coverage in The Lao PDR: Barriers and Policy Options (WP19)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Development Assistance in Health - How Much, Where Does It Go and What More Do Health Planners Need To Know? (WP21)Документ14 страницDevelopment Assistance in Health - How Much, Where Does It Go and What More Do Health Planners Need To Know? (WP21)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- Sustainable Health Financing in The Pacific (WP22)Документ14 страницSustainable Health Financing in The Pacific (WP22)Nossal Institute for Global HealthОценок пока нет

- NRF Nano EthicsДокумент18 страницNRF Nano Ethicsfelipe de jesus juarez torresОценок пока нет

- Soalan 9 LainДокумент15 страницSoalan 9 LainMelor DihatiОценок пока нет

- 2020 ROTH IRA 229664667 Form 5498Документ2 страницы2020 ROTH IRA 229664667 Form 5498hk100% (1)

- Epicor Software India Private Limited: Brief Details of Your Form-16 Are As UnderДокумент9 страницEpicor Software India Private Limited: Brief Details of Your Form-16 Are As UndersudhadkОценок пока нет

- OPSS1213 Mar98Документ3 страницыOPSS1213 Mar98Tony ParkОценок пока нет