Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

CAGV Takings Clause Materials

Загружено:

Helen BennettАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CAGV Takings Clause Materials

Загружено:

Helen BennettАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

CT Against Gun Violence, Inc. Phone: 203-335-3802 Email: ronpinciaro@aol.

com

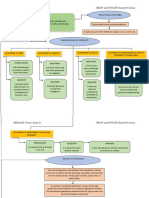

A. Although There are no Clear Tests to Predict Court Behavior in Takings Cases, the United States Supreme Court has Outlined a Multi-Step Approach to Takings Claims. The United States Constitutions Fifth Amendment's takings clause states, nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation. This clause is incorporated against the states through the Fourteenth Amendment due process clause. Chicago, B. & Q. R. Co. v. Chicago, 166 U.S. 226 (1897). 1. The Supreme Court draws an important distinction between cases involving physical takings and regulatory takings. In approaching a takings claim, the Supreme Court draws a distinction between physical takings and regulatory takings. Brown v. Legal Foundation of Washington, 123 S.Ct. 1406, 1417 (2003). a. Physical takings A physical taking occurs where the government acquires private property for a public purpose, whether the acquisition is the result of a condemnation proceeding or a physical appropriation. Id. In these cases, the Supreme Court has held that the Fifth Amendments plain language requires the payment of compensation. Id. The Brown court cited examples of physical takings: [C]ompensation is mandated when a leasehold is taken and the government occupies the property for its own purposes, even though that use is temporary. Similarly, when the government appropriates part of a rooftop in order to provide cable TV access for apartment tenants; or when its planes use private airspace to approach a government airport, it is required to pay that share no matter how small. Id. (quoting Tahoe-Sierra Preservation Council, Inc. v. Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, 535 US 302, 321-23 (2002); see also Loretto v. Teleprompter Manhattan CATV Corp., 458 U.S. 419, 434 (1982), cable TV access case, finding a taking to the extent of the occupation, without regard to whether the action achieves an important public benefit or has only minimal economic impact on the owner, in cases where a regulation amounts to a permanent physical occupation of property.).

b. Regulatory takings With respect to regulatory takings cases, in which regulations prohibit a property owner from making certain uses of her private property, courts must engage in essentially ad hoc, factual inquiries to determine whether a takings violation has occurred, guided by a series of factors identified in Penn Central Transportation Co. v. City of New York, 438 U.S. 104 (1978). Brown, 123 S. Ct. at 1417-18 (quoting Penn Central, 438 U.S. at 124). Ad hoc inquiries are designed to allow careful examination and weighing of all the relevant circumstances. 123 S. Ct. at 1418 (quoting Palazzolo v. Rhode Island, 533 U.S. 606, 636 (2001)). The Brown court cited some past cases that were examined under the standard of regulatory takings, finding that, a government regulation that merely prohibits landlords from evicting tenants unwilling to pay a higher rent; that bans certain private uses of a portion of an owners property, or that forbids private use of a certain airspace does not constitute a categorical taking. Id. (quoting 535 U.S. at 321-23). 2. Where a case involves a regulatory takings challenge, a court will examine the regulation using the factors identified in Penn Central. In Penn Central, the owners of the Grand Central Terminal challenged as violating the takings clause a New York City landmark law that prohibited them from building an office building above the Terminal. In evaluating whether the regulation amounted to a regulatory taking, the Court considered a series of factors that continue to guide the analysis of regulatory takings today. [S]everal factors are particularly significant the economic impact of the regulation, the extent to which it interferes with investment-backed expectations, and the character of the governmental action. Loretto, 458 U.S. at 433 (discussing Penn Central analysis). In evaluating the economic impact of a regulation, a court will examine how depriving an owner of his or her property affects the value of the property and the owners ability to engage in the profitable use of it. A court may be inclined to find a takings clause violation where regulation has an unduly harsh impact upon an owners economic interests. Penn Central, 438 U.S. at 128. In considering the character of governmental action, a court will examine whether the government action is sufficiently justified by the public interests it serves. Regulation in matters of public welfare, including issues of health and safety, will be more resistant to a takings

claim. Id. at 125. From the Penn Central analysis, where government regulation of the use of property contributes to legitimate public purposes and does not prevent profitable uses of the property, regulation is more likely to be upheld against takings challenges. B. In Cases Involving Firearms Regulation, Courts Have Rejected Takings Claims. Because the analysis of regulatory takings clause challenges is highly contextual, most past cases will not be helpful to predicting a courts response to a takings clause challenge here. As discussed below, some courts avoid an analysis using the Penn Central factors, holding that the prohibition of certain firearms is a valid exercise of the police power, and therefore cannot be a compensable taking. Regardless of their approach, all of the cases suggest substantial deference to regulations designed to improve public welfare. 1. Fesjian v. Jefferson In Fesjian v. Jefferson, 399 A.2d 861 (D.C. Cir. 1979), plaintiffs raised a takings clause claim against a Washington, D.C. firearms law that prohibited registration of machine guns. It is particularly noteworthy that the statute did not contain a grandfather clauseplaintiffs weapons had, in fact, been lawfully registered in prior years. The District code required that, within seven days, an unsuccessful firearm registration applicant must (1) peaceably surrender the firearm to the chief of police, (2) lawfully remove the firearm from the District for as long as he retains an interest in the firearm, or (3) lawfully dispose of his interest in the firearm. Id. at 865 (quoting D.C. Code 1978 Supp., 6-1820(c)). Although it did not use the terms physical taking or regulatory taking (a distinction articulated in more recent Supreme Court jurisprudence) the District of Columbia Court of Appeals firmly rejected the takings argument. The court cited Lamm v. Volpe, 449 F.2d 1202 (10th Cir. 1971), to support that a taking for the public benefit under a power of eminent domain is...to be distinguished from a proper exercise of police power to prevent a perceived public harm, which does not require compensation. 399 A.2d at 866. In Lamm, the Tenth Circuit, in rejecting plaintiffs claim that Congress determination that the removal of outdoor advertisements from highways required just compensation was a usurpation of Colorados police power, outlined the differences between police power and eminent domain: We recognize that police power is a matter of legislative prerogative. In this field the legislature has wide discretionary powers. It includes everything essential to

public safety, health, and morals. Police power should not be confused with eminent domain, in that the former controls the use of property by the owner for the public good, authorizing its regulation and destruction without compensation, whereas the latter takes property for public use and compensation is given for property taken, damaged or destroyed. Lamm, 449 F.2d at 1203. Acknowledging the three alternative ways that a person could dispose of an unregisterable firearm, the Fesjian court concluded, That the statute in question is an exercise of legislative police power and not of eminent domain is beyond dispute. The argument of petitioner, therefore, lacks merit. 399 A.2d at 866. The Fesjian court held that strict gun control regulations, regulations that in effect prohibited the possession of machine guns, did not constitute a takings requiring just compensation, finding instead that the firearms restrictions at issue were part of the legitimate range of state police power. Though the court avoiding the Penn Central factors, one can infer from its holding that the economic effects of the regulation were not so burdensome as to render the statute a takings violation. 2. Quilici v. Village of Morton Grove Citing the analysis in Fesjian, the Illinois District Court in Quilici v. Village of Morton Grove, 532 F. Supp. 1169 (N.D. Ill. 1981) upheld Morton Grove's general ban on handgun possession against a takings clause argument raised by plaintiff handgun owners. Analyzing the bans impact on the plaintiffs through the Penn Central factors, which implies that the regulation was not a physical taking, the court held that it did not result in the destruction of the use and enjoyment of a legitimate private property right and did not therefore require compensation. Id. at 1184. The court observed that though the possession of handguns was prohibited within the village, the statute still allowed handgun owners to engage in some uses of their firearms, uses similar to those allowed under the District of Columbia statute at issue in Fesjian: The geographic reach of the ordinance is limited; gun owners who wish to may sell or otherwise dispose of their handguns outside of Morton GroveIf handgun owners do not wish to sell their weapons, they may simply register and store them at a licensed gun club. Finally, the ordinance has an exception for licensed collectors, for whom neither of those two alternatives may be acceptable. Id. (see also Garcia v. Village of Tijeras, 108 N.M. 116, 124 (N.M. Ct. App. 1998), discussed below).

Because the takings argument was initially raised by plaintiffs and later abandoned, the courts analysis of this argument is dicta. The analysis in Morton Grove reaffirms the premise asserted in Fesjian, i.e., that a ban on a class of firearms will likely be upheld if it does not completely preclude an individuals ability to use or enjoy his or her propertys value and does not exclusively require the relinquishment of the firearms to law enforcement authorities. 3. Gun South Inc. v. Brady The Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals engaged in a similar analysis in Gun South, Inc. v. Brady, 877 F.2d 858 (11th Cir. 1989), where plaintiffs Gun South, Inc. (GSI) challenged the federal governments temporary ban on the importation of assault rifles. While the court dismissed the takings claim as a jurisdictional matter, it still examined the factors identified in Penn Central and found that no compensable taking had occurred. First, the Government has acted in a purely regulatory capacity and does not profit from its actions. Second, the Government has neither permanently nor totally deprived GSI of any property because the Government has only temporarily suspended the importation of such rifles. Finally, even though GSI may have had a reasonable investment-backed expectation, GSI does not demonstrate that the suspension will unreasonably impair the value of the rifles. Id. at 869. 4. Citizens for a Safer Community v. City of Rochester In Citizens for a Safer Community v. City of Rochester, 627 N.Y.S.2d 193 (N.Y. Gen. Term 1994), the Supreme Court of New York upheld Rochesters assault weapons ban against plaintiffs takings claim. Although Rochester does not grandfather previously owned weapons and only offers assault weapons licenses in a limited number of circumstances, plaintiffs argument appeared to only claim that the limitation on an owners right to sellconstitutes a taking of property and an unlawful interference with the dominion and control of a property in violation of federal and New York state law. Id. at 202. The court called this a mischaracterization of the ordinance, noting that the ordinance only limits an individual, whether a resident or not, from selling a gun, except through a licensed gun dealer, if such sale is to occur within the City of Rochester, placing no limits on gunsmiths and gun dealers who may sell firearms, and no limits on the rights of residents to sell firearms outside the city or to sell licensed firearms within it. Id. The court concluded that the ban does not deprive anyone of

any property, and does not result in the taking of any property for public purpose or otherwise. Id. 5. Silveira v. Lockyer In Silveira v. Lockyer, 312 F.3d 1052 (9th Cir. 2002), the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Californias assault weapons ban against a takings claim, observing that, It is wellestablished, however, that a government may enact regulations pursuant to its broad powers to promote the general welfare that diminish the value of private property, yet do not constitute a taking requiring compensation, so long as a reasonable use of the regulated property exists. Id. at 1092. Since the California ban allowed owners of grandfathered assault weapons to use the weapons in a number of reasonable ways so long as they register them, the court concluded that no compensable taking had occurred. C. Other Takings Cases Suggest Judicial Deference to Public Safety Regulation. Public welfare regulation has been given similar latitude in other contexts. In Hamilton v Kentucky Distilleries & Warehouse Co., 251 U.S. 146 (1919), the Supreme Court addressed a statute that prohibited the sale and transfer of liquor for beverage purposes within the United States, although allowing its export, and allowed seven months after its enactment for the unrestricted sale and transfer of liquor, to allow those engaged in the business to dispose of stocks on hand at the date of its enactment. Id. at 157. Noting the need to free up the lines of transportation to concentrate on war efforts, the court found that, no reason appearswhy such a federal law should be obnoxious to the Fifth Amendment. Id. In South Dakota Dept. of Public Safety ex rel. Melgaard v. Haddenham, 339 N.W.2d 786 (S.D. 1983), a case involving a statute that prohibited the sale of fireworks to South Dakota residents, the South Dakota Supreme Court responded to a takings claim by emphasizing the importance of regulating fireworks. Quoting the Washington Supreme Court's approach to a fireworks regulation case, the court held that, The power of government to regulate and restrain the use of fireworks cannot be denied. Indeed, considering the nature of the product, that power is better described as a duty when we think of the destructive nature of explosives and the danger to life and property attendant upon its use. Id. at 790 (quoting Ace Fireworks Co. v. City of Tacoma, 455 P.2d 935, 937 (Wash. 1969)).

The Court of Appeals of New Mexico dismissed a takings claim against a ban on the possession of pit bull dogs in Garcia v. Village of Tijeras, 108 N.M. at 123. Citing the Quilici takings analysis, the court noted that the prohibition had a limited geographic scope, affecting only the village, and allowed owners to remove their dogs from the village without punishment. Moreover, the village notified everyone prior to enforcing the ordinance. Id. at 124. The court stated that, The ordinance, being a proper exercise of the Villages police power, is not a deprivation of property without due process even though it allows for the destruction of private property[T]he Village has legitimately exercised the police power to curtail a menace to the public health and safety. D. Californias Takings Clause is Similar to the Fifth Amendment Takings Clause and Claims Under Both Clauses are Evaluated in Similar Ways. The takings clause of the California Constitution, art. I, 19, provides that, Private property may be taken or damaged for public use only when just compensation, ascertained by a jury unless waived, has first been paid to, or into court for, the owner. While the language is slightly different from the Fifth Amendments language, a courts analysis proceeds in a similar fashion. In Action Apartment Ass'n v. Santa Monica Rent Control Bd., 114 Cal. Rptr. 2d 412 (Cal. Ct. App. 2001), the California Court of Appeals addressed a claim by a group of landlords arguing that the requirement that they pay three percent interest on tenants security deposits constituted a taking where the interest rates were less than three percent. In finding that the landlords raised a valid takings claim, the court articulated the standard for examining whether regulation violates the California takings clause. As a matter of law, First, government action that effectuates a permanent physical invasion of property, no matter how slight, constitutes a per se takingSecond, regulatory action that deprives an owner of all economically beneficial or productive use of land effects a taking as a matter of law. Id. at 423 (quoting Cwynar v. City and County of San Francisco, 90 Cal. App. 4th 637, 652 (Cal. Ct. App. 2001), holding that regulation forbidding property owners from evicting tenants so that family members could move in might constitute direct and permanent physical invasion of property by government). These two categories appear analogous to the category identified as physical takings in the federal approach.

The Action Apartment Ass'n court acknowledged that most cases do not fall into one of the takings per se categories and would require a more scrutinizing analysis through the use of a two-part test (which the court acknowledged was often applied as two separate tests). 114 Cal. Rptr. 2d at 423. First, regulation constitutes a taking if it does not advance a legitimate state interest. Id. Second, the court may find a taking by weighing the Penn Central factors and observing the economic impact upon the property owner. Id. at 425.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Be Jar Whistleblower DocumentsДокумент292 страницыBe Jar Whistleblower DocumentsHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- MCQs On RTI Act - 89Документ16 страницMCQs On RTI Act - 89Ratnesh Rajanya83% (6)

- Finn Dixon Herling Report On CSPДокумент16 страницFinn Dixon Herling Report On CSPRich KirbyОценок пока нет

- PEZZOLO Melissa Sentencing MemoДокумент12 страницPEZZOLO Melissa Sentencing MemoHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- (2018) RedekerGillGasser - Towards Digital Constitutionalism Mapping Attempts To Craft An Internet Bill of RightsДокумент18 страниц(2018) RedekerGillGasser - Towards Digital Constitutionalism Mapping Attempts To Craft An Internet Bill of RightsCarlos Diego SouzaОценок пока нет

- 5 Creation and Determination of Family and Communal Land or Property (Modes of Acquisition of Land)Документ18 страниц5 Creation and Determination of Family and Communal Land or Property (Modes of Acquisition of Land)Abraham Daniel Obulor100% (1)

- 17-12-03 RE04 21-09-17 EV Motion (4.16.2024 FILED)Документ22 страницы17-12-03 RE04 21-09-17 EV Motion (4.16.2024 FILED)Helen BennettОценок пока нет

- 75 Center Street Summary Suspension SignedДокумент3 страницы75 Center Street Summary Suspension SignedHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- West Hartford Proposed budget 2024-2025Документ472 страницыWest Hartford Proposed budget 2024-2025Helen BennettОценок пока нет

- National Weather Service 01122024 - Am - PublicДокумент17 страницNational Weather Service 01122024 - Am - PublicHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- Hunting, Fishing, And Trapping Fees 2024-R-0042Документ4 страницыHunting, Fishing, And Trapping Fees 2024-R-0042Helen BennettОценок пока нет

- TBL Ltr ReprimandДокумент5 страницTBL Ltr ReprimandHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- PURA 2023 Annual ReportДокумент129 страницPURA 2023 Annual ReportHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- Analysis of Impacts of Hospital Consolidation in Ct 032624Документ41 страницаAnalysis of Impacts of Hospital Consolidation in Ct 032624Helen BennettОценок пока нет

- Pura Decision 230132re01-022124Документ12 страницPura Decision 230132re01-022124Helen BennettОценок пока нет

- 20240325143451Документ2 страницы20240325143451Helen BennettОценок пока нет

- South WindsorДокумент24 страницыSouth WindsorHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- Commission Policy 205 RecruitmentHiringAdvancement Jan 9 2024Документ4 страницыCommission Policy 205 RecruitmentHiringAdvancement Jan 9 2024Helen BennettОценок пока нет

- 2024 Budget 12.5.23Документ1 страница2024 Budget 12.5.23Helen BennettОценок пока нет

- Hartford CT Muni 110723Документ2 страницыHartford CT Muni 110723Helen BennettОценок пока нет

- CT State of Thebirds 2023Документ13 страницCT State of Thebirds 2023Helen Bennett100% (1)

- Crime in Connecticut Annual Report 2022Документ109 страницCrime in Connecticut Annual Report 2022Helen BennettОценок пока нет

- District 4 0174 0453 Project Locations FINALДокумент6 страницDistrict 4 0174 0453 Project Locations FINALHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- District 3 0173 0522 Project Locations FINALДокумент17 страницDistrict 3 0173 0522 Project Locations FINALHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- District 1 0171 0474 Project Locations FINALДокумент7 страницDistrict 1 0171 0474 Project Locations FINALHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- Final West Haven Tier IV Report To GovernorДокумент75 страницFinal West Haven Tier IV Report To GovernorHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- District 3 0173 0522 Project Locations FINALДокумент17 страницDistrict 3 0173 0522 Project Locations FINALHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- Voices For Children Report 2023 FinalДокумент29 страницVoices For Children Report 2023 FinalHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- Hurley Employment Agreement - Final ExecutionДокумент22 страницыHurley Employment Agreement - Final ExecutionHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- District 1 0171 0474 Project Locations FINALДокумент7 страницDistrict 1 0171 0474 Project Locations FINALHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- University of Connecticut Audit: 20230815 - FY2019,2020,2021Документ50 страницUniversity of Connecticut Audit: 20230815 - FY2019,2020,2021Helen BennettОценок пока нет

- PEZZOLO Melissa Govt Sentencing MemoДокумент15 страницPEZZOLO Melissa Govt Sentencing MemoHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- The Misunderstood Patriot: Pio ValenzuelaДокумент4 страницыThe Misunderstood Patriot: Pio ValenzuelamjОценок пока нет

- Part I - Anglo Vs Samana Bay (Digest) WordДокумент2 страницыPart I - Anglo Vs Samana Bay (Digest) WordAnn CatalanОценок пока нет

- Manila Electric Vs YatcoДокумент6 страницManila Electric Vs Yatcobraindead_91Оценок пока нет

- Contract EssentialsДокумент3 страницыContract EssentialsNoemiAlodiaMoralesОценок пока нет

- Preventing and Disciplining Police MisconductДокумент75 страницPreventing and Disciplining Police MisconductChadMerdaОценок пока нет

- Public Administration Study PlanДокумент10 страницPublic Administration Study Planumerahmad01100% (1)

- Ninth Circuit Appellate Jurisdiction Outline - 9th CircuitДокумент452 страницыNinth Circuit Appellate Jurisdiction Outline - 9th CircuitUmesh HeendeniyaОценок пока нет

- Unclassified09.2019 - 092519Документ5 страницUnclassified09.2019 - 092519Washington Examiner96% (28)

- Technogas vs. CA - Accession Continua Builder in Bad FaithДокумент3 страницыTechnogas vs. CA - Accession Continua Builder in Bad Faithjed_sinda100% (1)

- Excellent Quality Apparel Vs Win Multiple Rich BuildersДокумент2 страницыExcellent Quality Apparel Vs Win Multiple Rich BuildersDarla GreyОценок пока нет

- Khilafat Movement SlidesДокумент14 страницKhilafat Movement SlidesSamantha JonesОценок пока нет

- Activity 1. For prelim in Oriental MindoroДокумент2 страницыActivity 1. For prelim in Oriental MindoroKatrina Mae VillalunaОценок пока нет

- International School Alliance v. QuisumbingДокумент2 страницыInternational School Alliance v. QuisumbingAnonymous 5MiN6I78I0100% (2)

- Consumer Protection ActДокумент14 страницConsumer Protection ActAnam Khurshid100% (1)

- PH and SoKor - UpdatedДокумент24 страницыPH and SoKor - UpdatedNestor BalladОценок пока нет

- NYP-09!12!08 Participation (F)Документ2 страницыNYP-09!12!08 Participation (F)Patrixia Sherly SantosОценок пока нет

- Unit I Structure of GlobalizationДокумент10 страницUnit I Structure of GlobalizationANGELA FALCULANОценок пока нет

- Serquina, Jessaine Julliane C. - 2-BSEA-Exercise 19Документ28 страницSerquina, Jessaine Julliane C. - 2-BSEA-Exercise 19Jessaine Julliane SerquiñaОценок пока нет

- Predicate OffencesДокумент4 страницыPredicate OffencesThomas T.R HokoОценок пока нет

- SC Judgement On Section 498A IPC Highlighting Misuse of Law Against Husbands 2018Документ35 страницSC Judgement On Section 498A IPC Highlighting Misuse of Law Against Husbands 2018Latest Laws Team100% (1)

- MCQ in Ba Economics-Public EconomicsДокумент18 страницMCQ in Ba Economics-Public Economicsatif31350% (2)

- Far Eastern Corporation Vs CAДокумент1 страницаFar Eastern Corporation Vs CAMaphile Mae CanenciaОценок пока нет

- CourtRuleFile - 3987DD3D CRPC Sec 125Документ9 страницCourtRuleFile - 3987DD3D CRPC Sec 125surendra kumarОценок пока нет

- MG204: Management of Industrial Relations Print Mode Assignment TwoДокумент4 страницыMG204: Management of Industrial Relations Print Mode Assignment Twokajol kristinaОценок пока нет

- The Government of India Act 1858Документ7 страницThe Government of India Act 1858binoyОценок пока нет

- EXtra Questions Treaty of VersailesДокумент5 страницEXtra Questions Treaty of VersailesSmita Chandra0% (1)

- Agapito Rom vs. Roxas and Co.-Exemption From CARP CoverageДокумент24 страницыAgapito Rom vs. Roxas and Co.-Exemption From CARP CoverageNix ChoxonОценок пока нет