Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Funkcija Provosta

Загружено:

Vlada MarkovicИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Funkcija Provosta

Загружено:

Vlada MarkovicАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Provost (civil) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about a civil

position. For other uses, see Provost (disambiguat ion). Look up provost or prvt in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. A provost (introduced into Scots from French) is the ceremonial head of many Sco ttish local authorities, and under the name prvt (French pronunciation: ?[p?evo]) was a governmental position of varying importance in Ancien Regime France. Contents 1 History 2 Scotland 3 France 3.1 Royal provosts 3.2 Provost Marshals 4 In fiction 5 See also 6 References History As a secular title, praepositus is also very old, dating to the praepositus sacr i cubiculi of the late Roman Empire, and the praepositus palatii of the Caroling ian court. The title developed in France from where it found its way into Scots, where in Scotland it became the style (as provost) of the principal magistrates of the Royal Burghs (roughly speaking, the equivalent of "mayor" in the rest of the UK) ("Lord Provost" in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen and Dundee), and into E ngland, where it is applied to certain officers charged with the maintenance of military discipline. A Provost Marshal is an officer of the army originally appo inted when troops are on service abroad (and now in the United Kingdom as well) for the prompt repression of all offenses. He may at any time arrest and detain for trial persons subject to military law committing offences, and may also carr y into execution any punishments to be inflicted in pursuance of a court martial (Army Act 1881, 74). A provost sergeant is in charge of the garrison police or regimental police. The 'Provost' also refers to the military police in general. The army pronunciation is 'Prov-oh'. Scotland Historically the provost was the chief magistrate or convener of a Scottish burg h council, the equivalent of a mayor in other parts of the English-speaking worl d. Previous to the enactment of the Town Councils (Scotland) Act 1900 various ti tles were used in different burghs, but the legislation standardised the name of the governing body as the provost, magistrates, and councillors of the burgh. Aft er the re-organisation of local government in Scotland in 1975, the title of Lor d Provost was reserved to Aberdeen, Dundee, Edinburgh and Glasgow, while other d istrict councils could choose the title to be used by the convener: in 1994 twen ty-two councils had provosts.[1] Similar provisions were included in the Local G overnment etc. (Scotland) Act 1994 whch established unitary council areas in 199 6. The area councils are allowed to adopt the title of provost (or any other) fo r the convener of the council, as are the area committees of the council. Some c ommunity councils which include former burghs also use the style for their chair men. France The word prvt (provost) applied to a number of different persons in pre-Revolution ary France. Following its historical meaning (from Latin praepositus), the term referred to a seignorial officer in charge of managing burgh affairs and rural e states and, on a local level, customarily administered justice. Therefore, at Pa

ris, for example, there existed the Lord Provost of Paris who presided a lower r oyal court and the Provost of Merchants (prvt des marchands), or Dean of Guild, he aded the burgh council and the burgh's merchant company. In addition, there were Provost Marshals (prvts des marchaux de France), the Provost of the Royal Palace ( prvt de l'htel du roi), otherwise known as the Lord High Provost of France (grand p rvt de France), and the Provost General (prvt gnral) or High Provost of the Mint (gran d prvt des monnaies). Royal provosts The most important and best known provosts, as part of the Kingdom's general org anization administered the scattered parts of the royal domain, were the royal p rovosts (prvts royaux), who were the lowest royal judicial officers of the land.[c larification needed] The title varied widely from province to province: castella ns (chtelains) in Normandy and Burgundy and vicars (viguiers) in the South. These titles were retained from earlier times when formerly independent provinces wer e conquered and subsumed under the French Crown. Royal provosts were created by the Capetian monarchy around the 11th century. Provosts replaced viscounts where ver a viscounty had not been made a fief, and it is likely that the provost posi tion imitated and was styled after the corresponding ecclesiastical provost of c athedral chapters. Royal provostships were double faceted. First, provosts were entrusted with and carried out local royal power, including the collection of the Crown's domainal revenues and all taxes and duties owed the King within a provostship's jurisdict ion. They were also responsible for military defense such as raising local conti ngents for royal armies. Until the end of the Old Regime, a number of military p rovost (prevots d'pe) positions survived until being replaced by a lord lieutenant in administering justice. Finally, the provosts administered justice though wit h limited jurisdiction. For instance, they had no jurisdiction over noblemen or feudal tenants (hommes de fief) who instead fell under the jurisdiction of their lord's court and were tried before a jury of their peers, that is, the lord's o ther vassals. Provosts had no jurisdiction over purely rural areas, the pies pay s, which instead fell to local lordships. Provost jurisdiction was restricted to towns but was often usurped by Burgh courts chaired by burgesses. However, in the 11th century, the provosts tended increasingly to make their pos itions hereditary and thus became more difficult to control. One of the King's g reat officers, the Great Seneschal, became their supervisor. In the 12th century , the office of provost was put up for bidding, and thereafter provosts were far mers of revenues. The provost thus received the speculative right to collect the King's seignorial revenues within his provostship. This remained his primary ro le. Short-term appointments also helped stem the heritability of offices. Very e arly, however, certain provostships were bestowed en garde, i.e., on condition t he provost regularly render accounts to the King for his collections. Farmed pro vostships (prvtes en ferme) were naturally a source of abuse and oppression. Natur ally, too, the people were discontent. Joinville told of how under St Louis the provostship of Paris became an accountable provostship (prvt en garde). With the de ath of Louis XI, farmed provostships were still numerous and spurred a remonstra nce from the States General in 1484. Charles VIII promised to abolish the office in 1493, but the office is mentioned in the Ordinance of 1498. They disappeared in the 16th century, by which time the provosts had become regular officials, t heir office, however, being purchasable. Further oversight and weakening of provostships occurred when, to monitor their performance and curtail abuses, the Crown established itinerant justices known a s bailies (bailli) to hear complaints against them. With the office of Great Sen eschal vacant after 1191, the bailies became stationary and established themselv es as powerful officials superior to provosts. A bailie's district is called a b ailliary (baillage) and included about half a dozen provostships. When appeals w ere instituted by the Crown, appeal of provost judgments, formerly impossible, n

ow lay with the bailie. Moreover, in the 14th century, provosts no longer were i n charge of collecting domainal revenues, except in farmed provostships, having instead yielded this responsibility to royal receivers (receveurs royaux). Raisi ng local army contingents (ban and arrire-ban) also passed to bailies. Provosts t herefore retained the sole function of inferior judges over vassals with origina l jurisdiction concurrent with bailies over claims against nobles and actions re served for royal courts (cas royaux). This followed a precedent established in t he chief feudal courts in the 13th and 14th centuries in which summary provostsh ip suits were distinguished from solemn bailliary sessions (assise). The provost as judge sat a single bench with sole judicial authority over his Co urt. He was, however, required to seek the advice of legally-qualified experts ( cousellors or attorneys) of his choosing, and, in so doing, was said to "summon his council" (appelait son conseil). In 1578, official magistrates (conseillersmagistrats) were created, but were suppressed by the 1579 Ordinance of Blois. Th e office was restored in 1609 by simple decree of the King's Council, but it was opposed by the Parlement courts and seems to have been conferred in but few ins tances. Provost Marshals French Provost Marshals were non-judicial officers (officiers de la robe courte) attached to the Marshalry (marchausse) under the Old Regime, equivalent to the ge ndarmerie after the Revolution. Originally, they were assigned to judge crimes c ommitted by people in the army, but over the course of the 14th and 15th centuri es, they gained the right to judge certain types of misdemeanors and felonies co mmitted by the military and civilians alike. They became fixed with set areas of authority, and the offences falling within their jurisdiction came to be called provost crimes (cas prvtaux). Provost crimes included high violent crimes and cri mes committed by repeat offenders (repris de justice), who were familiarly known as the gibier des prvts des marchaux, or Provost Marshal jailbirds. They had milit ary jurisdiction, and their rulings were not appealable; however, the provost wa s required to keep a certain number of ordinary judges or masters. The Provost M arshal did not personally sit provost crime cases. Instead, this usually fell to the nearest bailliwick or presidial court. Presidial judges had concurrent juri sdiction with Provost Marshals, and the two vied openly to be vested.

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- ICC Afghanistan Board Members & LeadershipДокумент189 страницICC Afghanistan Board Members & Leadershipnedia100% (1)

- DLI Korean HeadstartДокумент490 страницDLI Korean HeadstartneonstarОценок пока нет

- List of German Monarchs: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaДокумент13 страницList of German Monarchs: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaAszOne SamatОценок пока нет

- 4 Dome..Engle.Документ2 страницы4 Dome..Engle.Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- 4 Dome..Engle.Документ2 страницы4 Dome..Engle.Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- 3 Ana - Rom.Документ1 страница3 Ana - Rom.Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- 5 Djur, Ilijci.c.stefana VitezДокумент1 страница5 Djur, Ilijci.c.stefana VitezVlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- 2 Crkva Svi Svetih, Moskav..Документ1 страница2 Crkva Svi Svetih, Moskav..Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Klementin - Prolaz 2Документ1 страницаKlementin - Prolaz 2Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- 4 Yuyiko PolikoppДокумент1 страница4 Yuyiko PolikoppVlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- 1 ZaradyojeeДокумент2 страницы1 ZaradyojeeVlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Apost - Palata 1Документ1 страницаApost - Palata 1Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- 1 Manor - Engleski Posed.Документ2 страницы1 Manor - Engleski Posed.Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Niko - Kapela 3Документ1 страницаNiko - Kapela 3Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- 4 Yuyiko PolikoppДокумент1 страница4 Yuyiko PolikoppVlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Implemented in Practice The Principl 2Документ1 страницаImplemented in Practice The Principl 2Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Kon - Vojska 1Документ2 страницыKon - Vojska 1Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- 1 GtgkjkumggДокумент1 страница1 GtgkjkumggVlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Spring - Bitka 2Документ2 страницыSpring - Bitka 2Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- 2 Hari Separd DДокумент2 страницы2 Hari Separd DVlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Stevca MoldavacДокумент1 страницаStevca MoldavacVlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- R.loara 2Документ2 страницыR.loara 2Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Ds.4 MerovinДокумент3 страницыDs.4 MerovinVlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- GR - Mez 5Документ3 страницыGR - Mez 5Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- H.jac 3Документ1 страницаH.jac 3Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Okup Domin 1Документ2 страницыOkup Domin 1Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Orl - An 3Документ2 страницыOrl - An 3Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Bas - Zaliv 1Документ1 страницаBas - Zaliv 1Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- West, Kaunt 4Документ1 страницаWest, Kaunt 4Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Rokc Kaunti5Документ1 страницаRokc Kaunti5Vlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Ujiii KHK LhjkyДокумент1 страницаUjiii KHK LhjkyVlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- JKFBN HBB GbbbjyДокумент2 страницыJKFBN HBB GbbbjyVlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- Jy GftyvjjdДокумент1 страницаJy GftyvjjdVlada MarkovicОценок пока нет

- ACCOM 2021 (Updated)Документ12 страницACCOM 2021 (Updated)Jomar LozadaОценок пока нет

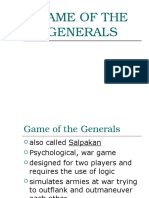

- Game of The Generals 1227420524646565 8Документ20 страницGame of The Generals 1227420524646565 8Maria Fe VillarealОценок пока нет

- PDF SeniorPoliceOfficersContactListДокумент14 страницPDF SeniorPoliceOfficersContactListV M (MV)Оценок пока нет

- Comaprative Police SystemДокумент59 страницComaprative Police SystemRochel Mae DupalcoОценок пока нет

- Lindang National High School DocumentsДокумент4 страницыLindang National High School DocumentsLasola HansОценок пока нет

- Durusul Lughah Al Arabiyah 3Документ143 страницыDurusul Lughah Al Arabiyah 3Ubaidillah Elz CruizerОценок пока нет

- G.O.Rt - No.298, DT 24.02.2024 (IGP)Документ1 страницаG.O.Rt - No.298, DT 24.02.2024 (IGP)magnetmarxОценок пока нет

- 03 Senior Civil Judge OcrДокумент23 страницы03 Senior Civil Judge OcrHemendra KapadiaОценок пока нет

- Industry Company Name Website Genreal Email: Biotechnolog Financial Serv Internet InternetДокумент5 страницIndustry Company Name Website Genreal Email: Biotechnolog Financial Serv Internet InternetYeasin ArafatОценок пока нет

- Rulers of GermanyДокумент180 страницRulers of GermanyPolemonis100% (1)

- Controlling Noise Pollution in MaharashtraДокумент9 страницControlling Noise Pollution in MaharashtraAbhimanyu Yashwant AltekarОценок пока нет

- You Paid For It Examines St. Louis Economic Development Partnership's Six-Figure Salaries, High-Priced OfficesДокумент8 страницYou Paid For It Examines St. Louis Economic Development Partnership's Six-Figure Salaries, High-Priced OfficesKevinSeanHeldОценок пока нет

- Origins of The Noncommissioned Officer CreedДокумент17 страницOrigins of The Noncommissioned Officer CreedDan Elder100% (3)

- Lancaster Primary CandidatesДокумент22 страницыLancaster Primary CandidatesPennLiveОценок пока нет

- List of SQAC DQAC SISC DISC 2019 20Документ39 страницList of SQAC DQAC SISC DISC 2019 20Shweta jainОценок пока нет

- List of PNP Personnel Qualified To Received Combat Incentive Pay PERIOD COVERED: For The Month of July 2021Документ3 страницыList of PNP Personnel Qualified To Received Combat Incentive Pay PERIOD COVERED: For The Month of July 2021Christian AbawagОценок пока нет

- Rejection List of The Candidates For The Post of Sub-Inspector of Police, Post Code-584Документ87 страницRejection List of The Candidates For The Post of Sub-Inspector of Police, Post Code-584Anil SharmaОценок пока нет

- 2021 List of Candidates For The May 18, 2021 ElectionДокумент25 страниц2021 List of Candidates For The May 18, 2021 ElectionPennLiveОценок пока нет

- Enhancement 9 - Comparison of PNP and AFPДокумент8 страницEnhancement 9 - Comparison of PNP and AFPKarecelVillaseBetenioОценок пока нет

- IPS Civil List-2019 Web PDFДокумент31 страницаIPS Civil List-2019 Web PDFaspirant443Оценок пока нет

- RTI Chapter XДокумент14 страницRTI Chapter XJaspreet SinghОценок пока нет

- Warsaw Pact and Yugoslav Ranks and UniformsДокумент59 страницWarsaw Pact and Yugoslav Ranks and UniformsBob AndrepontОценок пока нет

- Reenlistee 2023Документ2 страницыReenlistee 202373DRC HunterОценок пока нет

- Review Corps of Cadets Staff Chain-of-CommandДокумент1 страницаReview Corps of Cadets Staff Chain-of-CommandCrystal Guebone AyenciaОценок пока нет

- GI and GO 2017-2018Документ2 страницыGI and GO 2017-2018Michael CalungsodОценок пока нет

- Police Officers Transfer ListДокумент11 страницPolice Officers Transfer ListDavid MillerОценок пока нет

- Civil List IPS 2019 MasterДокумент40 страницCivil List IPS 2019 MasterAMOGH JAINОценок пока нет