Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Business Cycle Properties and Macro Forecasting of The Australian Economy: An Empirical Research Report

Загружено:

Brittany Vande WydevenИсходное описание:

Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Business Cycle Properties and Macro Forecasting of The Australian Economy: An Empirical Research Report

Загружено:

Brittany Vande WydevenАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Business Cycle Properties and Macro Forecasting of the Australian Economy:

An Empirical Research Report

Brittany Vande Wydeven, 312165048 The University of Sydney ECOS2002: Sem. 2, 2012 Word Count: 2,000

Executive Summary The purpouse of this paper is to obtain and analyze business cycle facts for Australia from 1996 to 2011, in order to make macroeconomic forecasts of Australias future economic state. Through using quarterly, detrended, and seasonally adjusted data, I was able to derive correlations, between the growth in output and in major indicators, to disocver both the cycical nature and properites of these policy related statistical figures.

Vande Wydeven, 2

Introduction

Lahiri and Moore (1992) reveal that the leading indicator approach is based on the idea that business cycles of indicator variables have repetitive expanding and contracting sequences which can aid in predicting a countrys future business cycle and economic activity. This paper documents and analyzes the business cycle facts of Australias inflation rate, nominal exchnage rate, private final consumption expenditure, gross fixed investment, unmeployment rate, labor productivity, short-term and long-term interest rate, money supply, and trade balance, in hopes that their correlation to GDP will help predict the future macroeconomic state of Australia. When combined with macroeconomic theory and policy models, these derived business cycles will provide a benchmark for further inquiry on Australias expectant macroeconomic happenings.

Part 1:

Business Cycle Facts and Economic Explanations on the Movement of Indicators

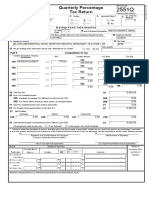

Table 1 reports the quarterly Australian data series for the period 1996-2012. Statistical measures for the cyclical components of various Australian macroeconomic indicators are shown above. The natural growth rate was taken of all aggregate variables, that when plotted against time had a consistent increase or decrease; I de-trended the series in order to reveal actual fluctuations in the variables once population growth was held constant. Most rate variables, besides unemployment rate, did not have a trend and therefore statistical measures were applied directly to the data found on ABS.

Vande Wydeven, 3

Inflation Rate: The cross-correlation between the growth rate of GDP and the inflation rate is largest in column X(t+1), revealing the series lags the cycle by one quarter and is responding to changes in Australias output during period t. This can be explained by the Central Bank enforcing an expansionary monetary policy in attempt to achieve economic growth. By the CB increasing the price target, firms are getting more money for their goods and consequently will produce more to increase profits. In the sort-run, the CB buys bonds to increase the money supply and decrease the interest rate for each Y (a rightward shift in LM). In the medium run, as seen through the quarter lag, the change in output will reflect a greater change in price and a higher inflation rate. AS will shift left to reflect a higher price for each Y, and output will shift back to the natural level of output. In the end, the price will rise even further then in the short-run. The inflation rate has a counter-cyclical nature at -0.32. When the overall economy is slowing down, the inflation rate is rising; this negative value can be explained through structural shocks such as the GFC. During a recession, the Australian government may want to run an expansionary fiscal policy and budget deficit in hopes that the increased interest rate and output will re-stabilize the economy. By increasing government spending, the IS curve shifts right, resulting in a rightward shift in the AD curve, and an increased price for each Y. Nominal Exchange Rate: The nominal exchange rate is a coincident indicator, because the cross-correlation is largest in period X(t). The series is contemporaneous with the cycle, in that a change in the nominal exchange rate occurs at the same time as a change in output; this is best understood through looking at the definition for GDP [Y= C+I+G+(X-M)]. Ceteris paribus, an increase in the GDP can be reflected by an increase in the amount of net exports in Australia. If Australias exports are increasing, then there is an increase in international demand for local goods and thus an increase in demand for Australian currency. The higher demand appreciates the $AU versus foreign currencies like the $US, meaning a stronger exchange rate. The nominal exchange rate is of a counter-cyclical

Vande Wydeven, 4

nature at -0.18. This seems counterintuitive, but may be explained if the trade balance strictly determines the business cycle behavior. During a recession the Australian government may run an expansionary fiscal policy, in hopes that increasing government spending will increase aggregate demand. The resulting higher interest rate may attract foreign investment to Australia, thus increasing the nominal exchange rate. Private Final Consumption: The correlation between private final consumption and the growth rate of GDP was contemporaneous and pro-cyclical at 0.37. This is to be expected since consumption is a component of GDP [Y=C+I+G+(XM)]. Ceteris paribus, an increase in consumption is reflected by an equivalent increase in output, revealed by a rightward shift of the IS curve in the short-run. The correlation is pro-cyclical because consumption is a factor of disposable income (Y-T), and output equals income. When the economy is experiencing a growth period, peoples income is higher, so they will spend more on goods. Gross Fixed Investment: Gross fixed investment is a coincident indicator because it is one of the largest components of GDP (Y=C+I+G) in a simplified closed economy. The cross-correlation was pro-cyclical at 0.5, which can be revealed through the AD relation and the fact that investment is a factor of both the interest rate and output. A lowered interest rate makes investment seem more attractive, and with an increase in investment comes an increase in output (interest rate effect on investment). Similarly, an increase in output increases investment even further because output equals income, and with more income comes more investment (output effect on investment).

Vande Wydeven, 5

Inventory Investment: Inventory investment is a minimal component of GDP and a weak indicator of the current economic state. However, my results indicated inventory investment leads the cycle by 5 quarters, which is explained in the ASAD model. Firms will cut production if they predict economic downturn (a leftward shift in AS), resulting in higher prices and lowered output, which will drive the economy further into a recession. Inventory Investment has a procyclical nature at 0.44, because during an economic decline, production slows, consumer and capital spending falls, unemployment rises, and profits fall. Unemployment Rate: The cross-correlation is largest in column X(t+1), revealing the series lags the cycle by one quarter. The ASAD model describes how unemployment here decreases a full quarter after GDP improves in period t. The aggregate supply curve is derived from the Wage-setting/Pricesetting relation, which determines the unemployment rate. The unemployment rate is directly related to output; when output increases there is a need for more workers to produce additional goods so the unemployment rate will drop [u=1-(Y/L)]. Okuns law supports this relation, in revealing that a 3% increase in output is followed by a 1% decrease in unemployment (Freeman 2001, p. 511). The cross-correlation statistical value is counter-cyclical at -0.35. The counter-cyclicality of the correlation reveals that the unemployment rate tends to decrease during economic booms and increase during recession periods. When the economy is growing, more individuals are needed to produce goods, resulting in a lowered unemployment rate. Labor Productivity: The cross-correlation was 0.61 in period X(t), revealing a highly pro-cyclical and contemporaneous series. Labor productivity growth is dependent on investment in physical capital, new technologies, and human capital (http://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/laborproductivity.asp#axzz29BTFrCm9). The Solow Model supports this pro-cyclical correlation, by revealing economic growth is

Vande Wydeven, 6

simultaneously dependent on these three factors. By definition (refer to Appendix A) labor productivity is a coincident indicator; if hours worked is held constant and real GDP, the numerator, increases then labor productivity would simultaneously increase. Short Term Interest Rate: The cross correlation was largest in period X(t+5), revealing the series lags the cycle by five quarters. The short-term interest rate therefore changes five quarters after the economy changes, which can be explained through the short-run ISLM model. Changes in the interest rates business cycle are due to monetary and fiscal policy changes (shifts in the IS or LM curve); therefore, the series would lag after these policies are enforced on the economy. The lagging nature of the short-term interest rate can also be attributed to the CB often altering i based on changes in the inflation rate, which as seen in a) tends to lag business cycle fluctuations. The cross-correlation is pro-cyclical at 0.24, revealing that it is positively correlated with the overall state of the economy. The short-run moneysupply/money-demand graph reveals that an increase in income, or by definition output, leads to an increase in money demand and consequently an increase in the short-term interest rate, due to a fixed money supply. Long Term Interest Rate: The long-term interest rate series leads the cycle by five quarters and is pro-cyclical at 0.24. Long-term interest rates are less variable then short-term interest rates, and less risky in terms of holding bonds. Therefore, individuals business decisions to invest, allocate resources, and consume are dependent on these rates. They are set by incorporating inflationary expectations and thus are pro-cyclical; to prevent inflation at the end of an economic growth period, the CB will raise the interest rate so that the opportunity cost of borrowing becomes greater and less people will demand money to invest. A yield spread, the difference between long and short-term interest rates, is commonly used to predict future economic growth in output, consumption, and investment, supporting long-term interest rates leading property.

Vande Wydeven, 7

Money Supply: The cross-correlation is largest in column X(t-4), revealing the series leads the cycle by four quarters. The ISLM relation reveals how output responds to changes in the Money Supply. An increase in the money supply shifts the LM curve right, therefore increasing output and decreasing the interest rate. The statistical value is counter-cyclical at -0.18, yet lacks significance because the magnitude is less than -0.2. The ISLM relation reveals that the money supply tends to increase when the overall economy is slowing down. During a recession, the CB may implement an expansionary monetary policy by increasing the money supply to spur economic growth from a lowered interest rate and elevated output (output and interest rate effects on investment).

Current Account Balance: During boom periods, imports would increase more than exports because people tend to spend more both domestically and internationally, revealing the counter-cyclical nature of the series. Even though my statistical representation was pro-cyclical at 0.24, graphically the trade balance is counter-cyclical in 1997, slightly in 2001, and majorly in 2008-2010. The growth of trade balance peaks around 2008 when the economy was in a global financial crisis. The pro-cyclical years may be periods when Australias growth was more export-led and dependent on oil prices, instead of based on domestic demand. The trade balance also lags by one quarter instead of being contemporaneous as expected, potentially from people waiting to purchase more goods from abroad after they see an increase in their income and after the exchange rates are determined.

Vande Wydeven, 8

Part 2:

Forecasting Variables (i) ABS gave a quarterly chain volume measure for Real GDP, revealing the production volume through holding prices constant. Regression of this data forecasted the Real GDP for 2012 Quarter IV at 349136.65 ($ millions) and at 357872.20 ($ millions) for 2013 Quarter I. In June 2012, the GDP was 345100.00. Consequently, GDP is forecasted to grow by 0.628% in 2012 and by 0.612% in 2013. (ii) I measured Australias inflation rate as the growth rate in the Consumer Price Index found on ABS. From this data, I ran statistical regressions forecasting the inflation growth rates in the 2012 Quarter IV and 2013 Quarter I. December 2012 is expected to be at 0.62% and March 2013 at 0.623%. (iii) The RBA sets monetary policy by changing the cash rate target, in order to maintain the target rate of inflation. At the last board meeting on October 3, 2012 the cash rate was lowered from 3.5% to 3.25%, and inflation rates were expected to remain consistent with the target over the next one to two years (http://www.rba.gov.au/media-releases/2012/mr-1230.html). Consequently, I believe the RBA will not change the cash rate target from 3.25% at the November 6th meeting. Although Australian GDP growth has slightly fallen due to decreasing residential investments, non-residential investments, and carbon prices affecting consumer prices (http://www.rba.gov.au/media-releases/2012/mr-12-30.html), I believe the RBA will wait to see the recent monetary policy effect the economy before lowering the cash rate even further to spur economic growth. (iv) The RBAs recent decision to lower the cash rate to 3.25% resulted in a weakened exchange rate in early October 2012 at an average of 1.0259, because the fallen interest rate impeded foreign investment (http://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/frequency/exchangerates.html). Generally, as a countrys inflation rate is being consistently lowered, their purchasing power should increase and their dollar should appreciate (http://www.investopedia.com/articles/basics/04/050704.asp#axzz29BTFrCm9). From September Q3 2011- September 2012, the inflation rate has consistently lowered from 3.6 to 1.2. Although this lowered inflation rate should reflect an appreciated AU currency, the fact that the interest rate is nearing the all time low of 3.0 is probably over-riding any possible inflation rate effects. Furthermore, Australia has had a tirelessly large current account deficit because of its minimal exports, resulting in a low exchange rate. After running a statistical regression from the quarter December 2000 onward, I expect to see the future exchange rate decrease from 1.0259 to 1.01 during the Nov 2012-June 2013 period. (v)

I

found

Australian

house

price

indices

by

running

a

regression

equation

of

the

price

index

of

established

houses:

weighted

average

of

8

capital

cities

from

March

1996

to

December

2012.

I

took

the

growth

rate,

from

the

Dec

2011

index

of

269.98

and

the

December

2012

index

of

278.58,

to

find

a

year-over-year

percentage

change

of

3.19%.

ABS

revealed

the

year-to-year

percentage

change

from

June

2011-June

2012

to

be

-2.1%,

thus revealing an overall increase in Australian house prices.

Vande Wydeven, 9

a) I forecasted GDP to grow on an average of .62% between 2012 and 2013 and inflation rates to grow on an average of .6215% between 2012 and 2013. I believed that the RBA would not alter its monetary policy and keep the interest rates at 3.25%, after their recent policy decision in October. Also, I expected the Australian dollar to depreciate from $1 AU=$1.0259 US to $1 AU= $1.01 US. The dollar can be depreciating due to the .62% growth in the inflation rates. The small growth in GDP can be attributed to the recent expansionary monetary policy imposed on October 3rd, 2012. I believe that this interest rate will not decrease and will remain at 3.25% for approximately three more years, in order to compensate for the recent lag in economic growth.

Conclusion

In the end, many of the derived cross-correlations were supported by macroeconomic theory and could be used to indicate future movements in the Australian business cycle. However, some statistical errors were made that may have altered the cyclical nature of the variables, the magnitude of the correlation, or the indicating properties; the trade balance business cycle was the least statistically and theoretically supported, and should be reexamined in future empirical research. Assumptions were created during forecasting, predicting very minimal growth in both GDP and the inflation rates. Similarly, I expected a weakened exchange rate and no alterations in the RBAs monetary policy. Overall, these combinations reveal Australians future business cycle may trend slightly downward, yet lack any major spikes or falls.

Appendix A: Definitions of Indicator Variables

Vande Wydeven, 10

Real GDP Definition: Inflation-adjusted measure of the value of all final goods and services produced in a year. Units: Chain volume measure. ($ Millions). Source: Australian National Accounts, ABS Cat No 5206.0 Labor productivity Definition: Real GDP divided by average hours worked. It reflects the growth in output based on factors of production other than hours worked. Units: Seasonally adjusted quarterly unemployment rate in decimals Source: Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure and Product, ABS Cat No 5206.0 Inflation Rate Definition: the rate at which the general level of prices of goods and services in an economy is rising over a period of time Units: percentage change in CPI beyond all quarters Source: Consumer Price Index, Australia, ABS Cat No 6401.0. Short-term interest rates: Definition: Australian 90-day bank bills Units: Seasonally adjusted quarterly growth rate of Australian 90-day bank bills in percentages Source: Australian Economic Indicators, ABS Cat No 1350.0. Long-term interest rates: Definition: Australian 10-year Treasury bonds Units: Seasonally adjusted quarterly growth rate of Australian 10-year Treasury bonds in percentages Source: Australian Economic Indicators, ABS Cat No 1350.0. Nominal Exchange Rate: Definition: The rate at which the Australian dollar is being exchanged for the US dollar ($1 AU=? $ US) Units: Seasonally adjusted quarterly growth rates in decimals Source: Australian Economic Indicators, ABS 1350.0 Private Final Consumption: Definitions: Since firm=investment, solely expenditure by households on individual consumption of goods and services Units: Seasonally adjusted quarterly growth rate of total annual household final consumption expenditure in decimals by chain volume measure ($millions). Source: Australian Economic Indicators, ABS Cat No 1350.0

Vande Wydeven, 11

Gross Fixed Investment: Definitions: A main component of GDP [Y=C+I+G+(X-M)], measuring the value of new or existing fixed assets of the business sector, households, and governments Units: Seasonally adjusted quarterly growth rate of total gross fixed capital expenditure in decimals Source: Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure, and Product, ABS Cat No 5206.0 Inventory Investment: Definitions: Minimal component of GDP that signifies the amount of produced goods left over from final sales in an economy. Units: The growth rate in percent of seasonally adjusted quarterly changes in inventories ($ millions). Source: Australian National Accounts: National Income, Expenditure, and Product, ABS Cat No 5206.0 Unemployment Rate: Definitions: Number of unemployed individuals divided by the labor force (employed + unemployed but actively seeking work) Units: Seasonally adjusted quarterly unemployment rates in percentages Source: Labour Force, Australia, ABS Cat No 6202.0 Money Supply: Definitions: M3, total monetary assets available at a given time Units: ($millions). Source: Australian Economic Indicators, ABS Cat No 1350.0 Trade Balance (Current Account Balance): Definitions: A component of GDP in an open economy. Exports minus imports over a particular period of time Units: Thousands Source: RBA, Balance of Payments, Current Account, Quarterly

Vande Wydeven, 12

References Brischetto, A., and Voss, G. (2002). Forecasting Australian Economic Activity Using Leading Indicators. Economic Research Department Reserve Bank of Australia, n/a, 1-27. http://www.rba.gov.au/publications/rdp/2000/pdf/rdp2000-02.pdf [Retrieved 1 October 2012] Unknown. (1996) G10 Gross Domestic Product. [online] Available at: http://agencysearch.australia.gov.au/s/search.html?collection=agencies&SF=CM&S M=both&form=simple&profile=abs&query=gdp+2012+&scope&sort&scope_=on&f .f+dc.format|f=xls [Accessed: 05 Oct 2012]. RBA: Minutes of Monetary Policy Meeting of the Board-7 February 2012. (n.d.). Reserve Bank of Australia - Home Page. http://www.rba.gov.au/monetary-policy/rba-boardminutes/2012/07022012.html [Retrieved 6 October 2012] RBA: Exchange Rates. (n.d.). Reserve Bank of Australia - Home Page. http://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/frequency/exchange-rates.html [Accessed 6 October 2012] Freeman, D. G. (2001), Panel Tests of Okun's Law for Ten Industrial Countries. Economic Inquiry, 39, 4, p. 511523. doi: 10.1093/ei/39.4.511 Lahiri, K., and Moor, G. (1992). Leading Economic Indicators: New Approaches and Forecasting Records - Google Books. Google Books. http://books.google.com.au/books?hl=en&lr=&id=_DkgJfo5snEC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1 1&dq=economic+indicator+approach&ots=2egm2F5UlP&sig=1lc-ll7_iXaAwwO1JIpoyVhqrI#v=onepage&q=economic%20indicator%20approach&f=false [Accessed 10 October 2012] Currency Trading Graphs. (n.d.). X-Rates http://www.xrates.com/graph/?from=USD&to=AUD [Accessed 5 October 2012] AUD/USD Forecast October 15-19. (2012, October 14). ForEX Crunch: Trade Forex Responsibly . www.forexcrunch.com/category/forex-weekly-outlook/aud-usdoutlook/ [Accessed: 14 October 2012] Abs.gov.au (2012) 1350.0 - Australian Economic Indicators, Jul 2012. [online] Available at: http://abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/1350.0Jul%202012?OpenDocu ment [Accessed: 10 Oct 2012]. Investopedia.com (2012) 6 Factors That Influence Exchange Rates. [online] Available at: http://www.investopedia.com/articles/basics/04/050704.asp#axzz29BTFrCm9 [Accessed: 10 Oct 2012]. Rba.gov.au (2009) RBA: Search for Statistics. [online] Available at: http://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/by-subject.html [Accessed: 04 Oct 2012]. Economicswebinstitute.org (2007) Exchange rate: a key concept in Economics. [online] Available at: http://www.economicswebinstitute.org/glossary/exchrate.htm [Accessed: 05 Oct 2012]. Books.google.com.au (1905) Macroeconomics for Today - Irvin B. Tucker - Google Books. [online] Available at: http://books.google.com.au/books?id=qXJWU5kTZlUC&pg=PA163&lpg=PA163&d q=leading+variable+macroeconomics&source=bl&ots=SLZv4d8sse&sig=dDqBTV9 dV7R2leeOlJyW66xMfvY&hl=en&sa=X&ei=qdZ4UNTrMaP_iAf9p4GoCw&ved=0

Vande Wydeven, 13

CCYQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=leading%20variable%20macroeconomics&f=false [Accessed: 04 Oct 2012].

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- AnnualReportAppendix PDFДокумент231 страницаAnnualReportAppendix PDFDeepika SundarОценок пока нет

- "A 30-Year Financial Experiment Has Come Crashing To End. Now We Need A Fairer Capitalism" (Will Hutton, Observer Economics Editor, 5 October 2008)Документ6 страниц"A 30-Year Financial Experiment Has Come Crashing To End. Now We Need A Fairer Capitalism" (Will Hutton, Observer Economics Editor, 5 October 2008)Edgington SchoolОценок пока нет

- Regionalism in Canada: The Forgotten DiversityДокумент37 страницRegionalism in Canada: The Forgotten DiversityHồ Tấn100% (1)

- KWCh06 4 Applying Consumer and Producer Surplus The Efficiency Costs of A Tax EdwardДокумент8 страницKWCh06 4 Applying Consumer and Producer Surplus The Efficiency Costs of A Tax EdwardAbraham Odoi GeraldОценок пока нет

- 14th Finance Commission - Report Summary PDFДокумент1 страница14th Finance Commission - Report Summary PDFSourav MeenaОценок пока нет

- Practice Multiple Choice QuestionsДокумент5 страницPractice Multiple Choice QuestionsAshford ThomОценок пока нет

- Market Equilibrium and The Determination of PricesДокумент35 страницMarket Equilibrium and The Determination of PricesNiña Alyanna Babasa Marte100% (1)

- Quarterly Percentage Tax Return: 12 - DecemberДокумент1 страницаQuarterly Percentage Tax Return: 12 - DecemberralphalonzoОценок пока нет

- Exercise Sheet 6Документ2 страницыExercise Sheet 6caduzinhoxОценок пока нет

- Essay Writing 2Документ5 страницEssay Writing 2Khyati DhabaliaОценок пока нет

- Daily 14.11.2013Документ1 страницаDaily 14.11.2013FEPFinanceClubОценок пока нет

- 69th Annual Report of TheДокумент67 страниц69th Annual Report of TheDiálogoОценок пока нет

- Reading: Rapid Urbanization: A Case StudyДокумент1 страницаReading: Rapid Urbanization: A Case StudyCarlos Tupa OrtizОценок пока нет

- Tax EvasionДокумент6 страницTax Evasionmoon walkerОценок пока нет

- AP Macroeconomics Practice Exam 2012Документ8 страницAP Macroeconomics Practice Exam 2012KatieОценок пока нет

- Major Recessionary Trends in India and Ways To Overcome It: Presented byДокумент34 страницыMajor Recessionary Trends in India and Ways To Overcome It: Presented byYogesh KendeОценок пока нет

- Tax Increment Financing TIF Districts in Oklahoma 2011Документ21 страницаTax Increment Financing TIF Districts in Oklahoma 2011Kaye BeachОценок пока нет

- Wages and Employment: The Classical View:According To Pigou, TheДокумент13 страницWages and Employment: The Classical View:According To Pigou, TheNisar Akbar KhanОценок пока нет

- Pestel Analysis of Retail BankingДокумент2 страницыPestel Analysis of Retail BankingShiv Shankar Chaudhary67% (3)

- Accenture Vs CirДокумент1 страницаAccenture Vs CirCess EspinoОценок пока нет

- Tutorial 9 Ak For Econ 1102Документ7 страницTutorial 9 Ak For Econ 1102Jonathan JoesОценок пока нет

- Budgeting in EducationДокумент4 страницыBudgeting in Educationvanessa adriano100% (2)

- AseanДокумент3 страницыAseanbryanОценок пока нет

- Notes in Contemporary WorldДокумент4 страницыNotes in Contemporary WorldJuan paoloОценок пока нет

- Economic Environment & Structural Changes in EconomyДокумент17 страницEconomic Environment & Structural Changes in EconomynirmalprОценок пока нет

- UPSC Prelims: Tip 1. Do Not Read Books From Cover To CoverДокумент7 страницUPSC Prelims: Tip 1. Do Not Read Books From Cover To CoverSandeep GhoraleОценок пока нет

- International Monetary System PDFДокумент27 страницInternational Monetary System PDFSuntheng KhieuОценок пока нет

- Empirical Analysis of Money Demand Function in Nigeria: 1986 - 2010Документ16 страницEmpirical Analysis of Money Demand Function in Nigeria: 1986 - 2010AnifaОценок пока нет

- The Effects of Inflation On Commercial Banks: G. J. SantoniДокумент12 страницThe Effects of Inflation On Commercial Banks: G. J. SantoniwmthomsonОценок пока нет

- Macro Economics MMSДокумент37 страницMacro Economics MMStuffman_amit100% (1)