Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Motivations For Passing Along Viral VideosAmong Young Adults (18-35)

Загружено:

meg.handerhanОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Motivations For Passing Along Viral VideosAmong Young Adults (18-35)

Загружено:

meg.handerhanАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Group A: Megan Handerhan, Jordan Wise, Hannah Townsend and Kelsey Hensley Dr.

Chris Yang May 10, 2012 COM 3928:101 Motivations for Passing Along Viral Videos Among Young Adults (18-35) INTRODUCTION The purpose of this study is to find out how young people aged 18-35 watch and pass along online videos, their attitudes toward passing along online videos, and their reasons and motivations of passing along viral videos. This study will show us how significant viral videos are to the younger generation and the impact it can make. There are several motivations regarding the passing along of viral videos which include: social influences, for personal fulfillment , for entertainment and for political reasons. These variables were tested and will later be discussed. LITERATURE REVIEW Watching and posting videos online became more popular a few years ago when websites like YOUTUBE came about. Those sites open the doors to people posting their own information or entertainment. People could have control and influence. Eighty percent of Internet users in the United States have viewed or downloaded an online video (Beyond Access[HY1] ). People have taken this idea further, to post videos uploaded by someone else. Some post to their social media site, some email to a friend, and some just pass a video along through personal interactions. Some of these videos are passed along so many times, they are said to be viral. What makes these videos become so popular? What makes people spread viral videos? According to the research and analysis of several articles, the motivation to forward and pass along viral videos may be broken into four categories: 1) social 2) personal fulfillment 3) entertainment and popular culture 4) political. Each of these categories can be broken down further to examine specific reasons.

The first motivation that leads to viral video sharing is social status . To be included, to gain attention and affection from others, and to control social standing are three main driving forces for video sharing linked with social relationships (Haridakis and Hanson 316-32). It has also been found that concepts of trust, normative influence and informational influence are positively associated with using social sites that involve these kinds of videos (Chu and Kim 4769). It can be interpreted that these same concepts can influence the sharing and forwarding of viral video ads. People want to feel included and informed and want to feel socially accepted. In addition, studies have shown that people who watch reality television with friends are more likely to post viral videos than those who watch alone. This idea is linked to the idea video sharing is a behavior most in line with the values of reality television because it leads to popularity or fame of participants (Stefanone 964-82). With this research, people seem to strive for a celebrity status, which would be similar to those of reality television stars. Video-sharing sites and the rise of viral videos opened up the idea that anyone can become famous (Kevin Allocca: Why videos go viral). Research also shows that people who are more outgoing in social setting post more than those who are more introverted. People who are more active in social sites online, who are digital literate, tend to share videos and enhance their digital literacy (Beyond Access). This influences online social status, a new concept. The second motivation is personal fulfillment. A study that coded 880 responses of motivations for consuming videos found that consumers did so because it was entertaining, relaxing, and interesting. Videos also offer a convenient escape from boredom (Chen 2008). The third motivation is entertainment. The use of celebrities as entertaining factors sparks interest and emotion, along with the likelihood of being shared. Research also shows that novelty plays an important role (Southgate, Westoby, and Page 349-65). In addition, sharing videos has become a form of entertainment and fun (Smith 559-61). It has become normal and is transforming into another form of entertainment, almost another part of social media. Celebrities and popular culture also influence viral video sharing by sharing videos themselves. When famous people or blogs share videos, they earn the label of tastemakers. Fans and followers become interested in these videos because someone in popular culture finds it important. This increases the likelihood of forwarding and sharing the video (Kevin Allocca: Why videos go viral).

The fourth motivation is political support. In the 2008 election, 25 percent of people turned to the Internet for political news and 4 in 10 of the younger cohort have watched political videos online (May 24-28). These videos began to go viral when campaign supports shared and reposted them (Wallsten 163-177). Research also shows that people share political videos to start discourse and democratic conversation ("Conference Papers -- International Communication Association" 1-22). Some political videos cross over to the entertainment motivation and involve levels of amusement and comedy ("Conference Papers -- International Communication Association" 1-22). This is an example of a primary motivation, political, and a secondary motivation, entertainment. Many of these motivations can follow this same idea, influencing on another. In conclusion, these four motives seem to be the most prevalent through our research. Social status (capitol), personal fulfillment, entertainment and popular culture and political information have been found to have the strongest links to viral videos and why students pass them. HYPOTHESES From what we found through previous studies, personal interviews, and other research, we were able to make several hypotheses about the motives for passing along viral videos. First, we concluded that college students pass along videos to gain social capital or improve social status, and this motive is positively correlated to the number of videos they pass. This leads to another, similar, hypothesis that people pass along videos to conform and be like others. In addition, we believe that students who watch many viral videos are more likely to pass those videos along. To go along with this, we believe that a students use in social networking sites influences them to pass along videos, and gives them a platform to do so. From our literature review, we were also able to hypothesize that there are political and informational motivations behind passing along viral videos. Lastly, we have also concluded personal fulfillment, whether it is entertainment or informational, is another motive. In order to analyze and test our hypotheses we use Pearsons Correlation and multiple regression.

THEORIES After finding out our testable hypotheses we came up with two theories to support them. The first theory we are able to apply is the theory of planned behavior. This theory links attitudes with perceived behavior to understand why a person performs certain actions (Ajzen). The theory states that attitude toward behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, together shape an individual's behavioral intentions and behaviors (Ajzen). Below is a model of the theory of planned behavior developed by Icek Ajzen. This theory applies to our research because in order to find out why young people view and pass along viral videos (behavior), we must find out their motivations (attitudes) for doing so.

The second theory we used is the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). TAM assumes that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use determine an individual's intention to use a system with intention to use serving as a mediator of actual system use (Furneaux 2006). In other words, TAM explains why and how users come to accept and use technology. The model, shown below, suggests that when a person is introduced with a new form of technology, such as social media or online videos, a number of factors will influence the way they use that technology. This model tests the theories behind a persons motive(s) to share viral videos because the TAM tells us that when a person is introduced to a new technology (viral videos) they will either accept or reject the technology, and if they accept it, they will find new ways to use the technology.

METHOD In order to get quantitative information to uncover information about viral video usage, our group conducted ten personal interviews each. As a group, we conducted forty interviews overall. We used convenience sampling for our personal interviews and the locations of the interviews varied between Boone and Raleigh, North Carolina. Over 90% of the people interviewed were college students ranging from 18-24 years old. We asked questions pertaining to typical Internet usage and the frequency of viral video sharing. If the interviewees did not share viral videos, we asked for their reasoning. This way, we gathered information about why they shared videos and why they did not share videos. We then asked how they shared videos with their friends, if it was through social networking sites or through email. We also asked how they felt when they received a viral video from a friend or relative. The next step in uncovering information about viral video usage, our class conducted a web survey that reached 2,700 students at Appalachian State University. We worked together as a class to develop a survey questionnaire with no more than forty questions based on our professors draft to find out how young people aged 18-35 watch and pass along online videos, their attitudes toward passing along online videos, and their reasons and motivations of passing along viral videos. Once the survey questionnaire was ready, we conducted a pilot survey and filled out twenty surveys as a test run. After the test run was complete, we hosted the survey on surveymonkey.com and began to choose our samples. We used random sampling by using the student phonebook for Appalachian State University. Our class was then sectioned off into three groups with each group reaching 900 students each. We then used our personal emails to contact students through their school email addresses. We did not send out the emails at once, instead we sent them out in intervals over a span of ten days. We hoped this would increase our chances of getting the most responses. In our

emails, we used a form letter provided by our professor. There was an incentive of the possibility of winning a $100 gift card for Amazon.com if the students decided to fill out the web survey. We provided an incentive in the hopes of increasing the response rate. (citation of some sort as to why we decided to use an incentive?) Once the first wave of web surveys were filled out, we then figured out which students did not complete the survey. After we figured out the nonrespondents we sent out another email reminding them of the $100 gift card incentive and how we did not have enough responses to conduct an accurate experiment. After two more days of sending out emails in waves of 100, we gathered enough web survey responses to be reliable. The measurement scale with response options ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree were adapted from Harvey, Steward, & Ewing (2011) and Huang, Lin, & Lin (2009). The questions pertaining to perceived recipients interest and perceived risks were based on 150 personal interviews of co-investigators and Palka, Pousttchi, & Wiedemann (2009). Image outcome expectations and affection outcome expectations were questions adapted from Huang, Lin, & Lin (2009). Survey questions that asked about normative pressures, perceived control perceived enjoyment, and perceived expressiveness were adapted from Nysveen et al. (2005). The final question relating to attitudes toward passing along online videos was adapted from Yang and Zhou (2011). We used the multiple regression and Pearson Correlation statistical methods to analyze the survey data. RESULTS We conducted Pearsons correlation to help us determine how accurate our hypotheses were. We found that there are positive correlations, but some motives having a stronger correlation than others.

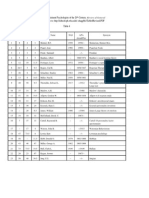

Overall, all of the hypotheses have a positive correlation because the sig. is less than .05. According to our data analysis, they are all significant at p < .05. All four of these are supported because there is a positive correlation significant at p < .05 level. They have different levels of relationships, however. There is a moderate to strong, positive relationship between intent to pass along viral videos and number of videos shared, with the Pearsons Correlation being 0.602. There is also a moderate, positive relationship between attitudes and intent, with a Pearsons Correlation .582. Pleasure and videos also share a moderate, positive relationship, with a Pearsons correlation of 0.467. There is a weak, positive relationship between affection and videos shared, as seen in a .326 Pearsons Correlation.

The dependent variable was the number of videos young people pass along. The variables listed above are the independent variables. According to multiple regression statistics, the independent variables including social media use, video watched, and intent are significant predictors because their beta weights are statistically significant at p < .05 level. In other words, the number of videos passed along are influenced by social media use, videos watched, and intent. DISCUSSION Our final survey research results have good reliability and validity. We should be able to draw some conclusions and make some recommendations for advertising practitioners or communication professionals regarding using viral videos. Our first hypothesis was that college students pass along videos to gain social capital or improve social status, and this motive is positively correlated to the number of videos they pass. Through our research, we found this to be correct. We also hypothesized that people pass along videos to build social capital of affection. Through our study this has also been found to be true. Our third hypothesis was also found to be correct. The idea that students who watch many viral videos are more likely to pass those videos along was found true through our research. Our hypothesis that students use in social networking sites influences them to pass along videos, and gives them a platform to do so was found to be correct as well.

A few of our hypotheses were not studied through our interviews and surveys. First, the hypothesis that there are political and informational motivations behind passing along viral videos. Also, we believed that personal fulfillment, whether it is entertainment or informational, is a motive for passing along videos. CONCLUSION Through our research we found that intent, attitudes, pleasure and affection are all motives for passing along videos. Intent has the strongest relationship, meaning that within the next seven days they plan to pass along viral videos to their friends. Attitudes has a moderate, positive relationship to passing along videos. Pleasure and affection both have a weak relationship, but are still positively correlated. This positive correlation throughout these motives prove they are all significant. LIMITATION AND FUTURE RESEARCH One of our major limitations was that the interviews and surveys we conducted did not examine either informative or political factors. Those were two of the major motives we found in our literature review and based our hypotheses on. This left us without any information about these categories and we were unable to make any conclusion. In the future, those are two motives that should be added to personal interviews and to the questionnaires and surveys. Our study was also hindered by the participants we had. We only interviewed students at Appalachian State University. This only gives us a small glimpse into college students as a whole. To make stronger generalizations, we should survey students from universities across the United States. This would give us a better overall idea of college students motives for passing viral videos. Maybe look at highschool students as well. Choose a range of different universities. Get more respondents. Look at more possible motives, rather than just social capital and attitudes. Income as a demographic variable should also be eliminated since most college students do not have a steady income and may still rely on their parents for money. Another limitation in our research was our lack of knowledge regarding statistical analysis and interpreting the data results. This hindered us from understanding the results properly and being able to decode their meanings. In the future, in able to have a better

understanding of data analysis and how to decode the data, we will need to increase our knowledge with regards to the statistical results . Our research would be easier to explain if these limitations didnt exist. All in all, we conclude that we need to spend more time conducting surveys, focus groups, interviews, convince samples, etc. in order to gain more results and maybe even more perspectives. We would further our research to different colleges, not just Appalachian State University. Most importantly, we would spend more time becoming more familiar with decoding and understanding the results of our research. After we eliminate and/or overcome these limitations, then we will be able to better our future research.

Works Cited Ajzen , I. (n.d.). Theory of planned behavior. Retrieved from http://people.umass.edu/aizen/tpb.html "Beyond Access: Differential Engagement in Online Video-Sharing Forums.." Conference Papers -- International Communication Association. (2010): 1-31. Print. Chu, Shu-Chuan, and Yoojung Kim. "Determinants of consumer engagement in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in social networking sites." (2011): 47-69. Print Furneaux, B. (2006, January 13). Technology acceptance model . Retrieved from http://www.istheory.yorku.ca/Technologyacceptancemodel.htm Haridakis, Paul, and Gary Hanson. "Social Interaction and Co-Viewing With YouTube: Blending Mass Communication Reception and Social Connection." Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. (2009): 316-32. Print. Kevin Allocca: Why videos go viral. TEDTalks, 2012. Web. 1 Mar 2012. <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BpxVIwCbBK0&feature=share>. May, Albert L. "Campaign 2008: It's on YouTube.."Nieman Reports. (2008): 24-28. Print. "Programmed by the People: The Intersection of Political Communication and the YouTube Generation."Conference Papers -- International Communication Association. (2007): 122. Print. Smith, Tom. " The social media revolution." International Journal of Market Research. 51.4 (2009): 559-61. Web. 1 Mar. 2012. <http://0 ehis.ebscohost.com.wncln.wncln.org/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=4e999f10-8cf141d7-8eae-e39a8b4fc7d9@sessionmgr13&vid=1&hid=6>. Southgate, Duncan, Nikki Westoby, and Graham Page. "Creative determinants of viral video viewing."International Journal of Advertising. (2010): 349-65. Web. 1 Mar. 2012. <http://ehis.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=ca5788f1-4eee-4ecf-a3b187cb1431b154@sessionmgr113&vid=2&hid=101>. Stefanone, Michael A. " Reality Television as a Model for Online Behavior: Blogging, Photo, and Video Sharing." Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. (2009): 964-82. Print.

"Understanding Content Consumers and Content Creators in the Web 2.0 Era: A Case Study of YouTube Users." Conference Papers -- International Communication Association. (2008): 1-30. Web. 1 Mar. 2012. Wallsten, Kevin. " WITP Yes We Can: How Online Viewership, Blog Discussion, Campaign Statements, and Mainstream Media Coverage Produced a Viral Video Phenomenon." Journal of Information Technology & Politics. 7 (2010): 163-177. Web. 1 Mar. 2012. <http://ebscohost.com>.

Вам также может понравиться

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Case Study PTSD FinalДокумент4 страницыCase Study PTSD Finalapi-242142838Оценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Carl JungДокумент17 страницCarl JungShahfahad JogezaiОценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- Sales ProposalДокумент16 страницSales Proposalmeg.handerhanОценок пока нет

- Sharpie Plans BookДокумент27 страницSharpie Plans Bookmeg.handerhan75% (4)

- The North Face Media PlanДокумент23 страницыThe North Face Media Planmeg.handerhan100% (2)

- Ethical Issues in Psychological ResearchДокумент5 страницEthical Issues in Psychological ResearchPrateekОценок пока нет

- DR Ruvaiz Haniffa: Dept. Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya 25 September 2006Документ17 страницDR Ruvaiz Haniffa: Dept. Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya 25 September 2006Nipun M. DasanayakeОценок пока нет

- Balint - The-Basic-Fault - Therapeutic Aspects of Regression PDFДокумент94 страницыBalint - The-Basic-Fault - Therapeutic Aspects of Regression PDFVicente Pinto100% (1)

- 1st Grading Exam Perdev With TosДокумент4 страницы1st Grading Exam Perdev With Toshazel malaga67% (3)

- Bermuda and Its Advertising IndustryДокумент17 страницBermuda and Its Advertising Industrymeg.handerhanОценок пока нет

- Caring Behaviours Interview Guidance 27 Nov 2014Документ10 страницCaring Behaviours Interview Guidance 27 Nov 2014MiriamОценок пока нет

- Albena YanevaДокумент16 страницAlbena YanevaIlana TschiptschinОценок пока нет

- Full Download Childrens Thinking Cognitive Development and Individual Differences 6th Edition Ebook PDFДокумент42 страницыFull Download Childrens Thinking Cognitive Development and Individual Differences 6th Edition Ebook PDFcarla.yarbrough78798% (41)

- Do Your Genes Make You A CriminalДокумент39 страницDo Your Genes Make You A CriminalParisha SinghОценок пока нет

- Metaethics Investigates Where Our Ethical Principles Come From, and What TheyДокумент3 страницыMetaethics Investigates Where Our Ethical Principles Come From, and What TheyMark AltreОценок пока нет

- Research Methods I FinalДокумент9 страницResearch Methods I Finalapi-284318339Оценок пока нет

- (Haggbloom, 2002) 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of The 20th CenturyДокумент5 страниц(Haggbloom, 2002) 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of The 20th CenturyMiguel MontenegroОценок пока нет

- Digit SpanДокумент10 страницDigit SpanshanОценок пока нет

- Disciplines and Ideas in The Social SciencesДокумент3 страницыDisciplines and Ideas in The Social SciencesNel PacunlaОценок пока нет

- Neuro Linguistic Programming - A Personnal Development Tool Applied To The Pedagogy and To The Improvment of Teachers - Students RelationsДокумент5 страницNeuro Linguistic Programming - A Personnal Development Tool Applied To The Pedagogy and To The Improvment of Teachers - Students RelationsJoão Magalhães MateusОценок пока нет

- Brand ExperienceДокумент51 страницаBrand ExperienceSy An NguyenОценок пока нет

- Educ 12Документ29 страницEduc 12Genalyn Apolinar GabaОценок пока нет

- Educ304 SPOC FINAL Module Guidance and Counseling 1Документ117 страницEduc304 SPOC FINAL Module Guidance and Counseling 1Jasper VillegasОценок пока нет

- The Basis of Performance ManagementДокумент25 страницThe Basis of Performance ManagementHans DizonОценок пока нет

- People Types and Tiger StripesДокумент258 страницPeople Types and Tiger StripesGigi ElizОценок пока нет

- FC 105 - Outline Scope PrelimsДокумент6 страницFC 105 - Outline Scope PrelimsSally SomintacОценок пока нет

- Interview Preparation Canvas 1647889623Документ1 страницаInterview Preparation Canvas 1647889623shohaibsadiqОценок пока нет

- Classroom Management PlanДокумент2 страницыClassroom Management Planapi-541765085Оценок пока нет

- Learning Module: Zamboanga Peninsula Polytechnic State UniversityДокумент44 страницыLearning Module: Zamboanga Peninsula Polytechnic State UniversityCharmelyn Jane GuevarraОценок пока нет

- Performance Managment - COДокумент7 страницPerformance Managment - COTesfaye KebedeОценок пока нет

- REFLECTIONДокумент2 страницыREFLECTIONShahirah IzzatiОценок пока нет

- All About Buying Lesson PlanДокумент8 страницAll About Buying Lesson Planapi-314360876100% (1)

- Developing The Whole PersonДокумент13 страницDeveloping The Whole PersonSarah jane AlmiranteОценок пока нет

- Local Media2351813422938379804Документ24 страницыLocal Media2351813422938379804Katrine ManaoОценок пока нет