Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

G40115 BRY 2011 Volume1

Загружено:

Fatema MohsinОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

G40115 BRY 2011 Volume1

Загружено:

Fatema MohsinАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

BUSINESS

RESEARCH

YEARBOOK

Balancing Profitability and Sustainability:

Shaping the Future of Business

VOLUME XVIII 2011

NUMBER 1

MARGARET A. GORALSKI

H. PAUL LEBLANC, III

MARJORIE G. ADAMS

Publication of the International

Academy of Business Disciplines

Cover Design by Tammy Senath ISBN 1-889754-16-1

GORALSKI

LEBLANC

ADAMS

EDITORS

BUSINESS

RESEARCH

YEARBOOK

Volume

XVIII

2011

Number 1

International

Academy of

Business

Disciplines

BUSINESS RESEARCH YEARBOOK

BALANCING PROFITABILITY AND SUSTAINABILITY:

SHAPING THE FUTURE OF BUSINESS

VOLUME XVIII 2011

NUMBER 1

Chief Editor

Margaret A. Goralski

Quinnipiac University

Associate Editor

H. Paul LeBlanc III

University of Texas at San Antonio

Managing Editor

Marjorie G. Adams

Morgan State University

A Publication of the

International Academy of Business Disciplines

I A B D

Copyright 2011

by the

International Academy of Business Disciplines

International Graphics

10710 Tucker Street

Beltsville, MD 20705

(301) 595-5999

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Co-published by arrangement with

The International Academy of Business Disciplines

ISBN

1-889754-16-1

i

PREFACE

Each year in April, members of the International Academy of Business Disciplines

(IABD) and invited guests come together to share their research and ideas to explore thoughts

with other academics, business leaders, policy makers, and students. This internationally refereed

publication is a glimpse into that research. It has been our pleasure as Editors to work with the

authors whose work appears in this issue of the Business Research Yearbook and the active track

chairs who have encouraged them along the way.

We are truly an international body with members traveling from, England, Spain, the

Middle East, India, Japan, China, and other countries worldwide to join us in personal,

community, and world growth. The objectives and far-reaching visions of the IABD have created

interest and excitement. We have evolved into a strong global organization due to the immense

support of many dedicated individuals and institutions.

The International Academy of Business Disciplines is a worldwide, non-profit

organization established to foster and promote education in all of the functional and support

disciplines of business. The objectives of IABD are to stimulate learning and understanding and

to exchange information, ideas, and research studies from around the world. The Academy

provides a unique global forum for professionals and faculty in business, communications, and

other social science fields to discuss common interests that overlap career, political, and national

boundaries. IABD creates an environment to advance learning, teaching, research, and the

practice of all functional areas of business.

The Business Research Yearbook is published to promote cutting edge research. We

thank the Board of Directors of the International Academy of Business Disciplines for their

dedication to the advancement of knowledge.

Margaret A. Goralski

H. Paul LeBlanc III

Marjorie G. Adams

ii

INTERNATIONAL ACADEMY OF BUSINESS DISCIPLINES

2011 REVIEWERS

Ahmad Tootoonchi, Frostburg State University

Amiso M. George, Texas Christian University

Antonio Noguero, University of Barcelona

Azam N. Foda, Decizens, Inc.

Becky McDonald, Ball State University

Bonita Dostal Neff, Valparaiso University

Cheryl O. Brown, University of West Georgia

Chulguen Yang, Southern Connecticut State

University

Chun-Sheng Yu, University of Houston-Victoria

Dale Steinreich, Drury University

Daniel W. Smith, Penn State University at Beaver

Darwin L. King, St. Bonaventure University

David Zoogah, Morgan State University

Diane Bandow, Troy University

Durriya H. Z. Khairullah, St. Bonaventure University

Enric Ordeix-Rigo, Ramon Llull University

Erich B. Bergiel, University of West Georgia

Felix Abeson, Coppin State University

Firhana Saifee, Western University

Habte-Giorgis, Berhe Rowan University

Hakan Altintas, Uludag University, Turkey

Harold W. Lucius, Rowan University

J. Gregory Payne, Emerson College ,

Jeff Rooks, University of West Georgia

John C. Tedesco, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and

State University

John Mark King, East Tennessee State University

June Lu, University of Houston-Victoria

Kathy Kabbani, California State University - Fresno

Kayong Holston, Ottawa University

Louis K. Falk, University of Texas at Brownsville

Majidul Islam, Concordia University

Margaret A. Goralski, Quinnipiac University

Marjorie G. Adams, Morgan State University

Marty Mattare, Frostburg State University

Michael J. Mitchell, International School of

Management, Paris

Mike Monahan, Frostburg State University

Mohammad Bsat, National University

Mohamed Khalil, Kennedy School of Government,

Harvard University

Nathan Austin, Morgan State University

Omar M. Al Nasser, University of Houston-Victoria

Omid Nodoushani, Southern Connecticut State

University

Paul A. Fadil, University of North Florida

Paul. B. Gwamna, Iowa Wesleyan College

Bisi Gwamna, independent editor and consultant,

Iowa

Spencer Kimball, Kimball and Associates

Steve Ugbah, California State University- East Bay

Stevina Evuleocha, California State University - East

Bay

Philemon Oyewole, Howard University

Philip Fuller, Jackson State University

Rabiz N. Foda, Hydro One Networks, Inc.

Raquel Casino, Independent Communications

Professional

Robert Page Jr., Southern Connecticut State

University

Samantha R. Dukes, University of West Georgia

Shakil M Rahman, Frostburg State University

Talha Harcar, Penn State University at Beaver

Tricia Hansen-Horn, University of Central Missouri

Wafa Elgarah, Al Akhawayn University, Morocco

Zahid Y. Khairullah, St. Bonaventure University

Ziad Swaidan, University of Houston-Victoria

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1: ACCOUNTING HISTORY ....................................................................... 1

The CPA Exam Past and Future

P. Michael Moore, University of Central Arkansas ....................................................... 2

The Annual Report and Corporate Social Responsibility

Annette Hebble, TUI University

Vinita Ramaswamy, University of St. Thomas .............................................................. 9

CHAPTER 2: ADVERTISING AND MARKETING COMMUNICATION............... 15

Social Networks - The Dark Side

Hy Sockel, DIKW Management Group

Louis K. Falk, University of Texas at Brownsville ..................................................... 16

Travelers Perceptions of Tennessee: Its a Rocky Top State (Of Mind)

Lisa Fall, University of Tennessee

Charles A. Lubbers, University of South Dakota ........................................................ 22

Adaptive Selling in the Public Arena: An Exploratory Investigation

George A. Kirk, Southern University

Richard L. McCline, Southern University

George M. Neely, Sr., Southern University ................................................................. 29

A Critical Theoretical Exploration of Municipal Budgets as Marketing Tools

Staci M. Zavattaro, University of Texas at Brownsville .............................................. 36

CHAPTER 3: APPLIED MANAGEMENT SCIENCE & DECISION SUPPORT

SYSTEMS.................................................................................................. 42

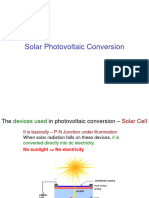

Economic Evaluation of Renewable Energies in Iranian Power Plant Industries Utilizing

Merit Rate Method

Seyed Mohammad Seyedhosseini, Islamic Azad University

SarahYousef,IranUniversityofScienceandTechnology ......................................... 43

An Information Systems Encounter with the Six Sigma Method

Roger L. Hayen, Central Michigan University ............................................................ 48

Ethical Decision Making Among Addicted and Non-Addicted Internet Users

Kimberly S. Young, St. Bonaventure University

Carl J. Case, St. Bonaventure University .................................................................... 55

iv

A Hybrid Fuzzy Mathematical Programming - Fuzzy ANP Model for R & D Project

Portfolio Selection

S.M. Seyedhosseini, Iran University of Science and Technology

S.M. Ghoreyshi, Iran University of Science and Technology ..................................... 62

CHAPTER 4: COMMUNICATION AND TECHNOLOGY ........................................ 70

A Web-based Multilingual Meeting System: Breaking The Language Barrier

Milam Aiken, University of Mississippi

John Wee, University of Mississippi

Mahesh Vanjani, Texas Southern University ............................................................... 71

Daimlers Bribery Crisis: A Casuistic Analysis of Daimlers Online Crisis Communication

Roxana Maiorescu, Purdue University ........................................................................ 77

Public Relations and Technological Advances: Consumers And An EcoCAR Campaign

Rachel Dobroth, Virginia Tech

Kaitlyn Redelman, Virginia Tech

John C. Tedesco, Virginia Tech.................................................................................... 83

Developing NFC Based Applications and Services: Innovation and Research Directions

ngeles Sandoval Prez, University of Vigo

Irene Garrido Valenzuela, University of Vigo

Paloma Bernal Turnes, University Rey Juan Carlos .................................................... 89

CHAPTER 5: COMPUTER INFORMATION SYSTEMS ........................................... 96

Balancing Between Using Open Source and Commercial Software in a Technology Program

Azad Ali, Indiana University of Pennsylvania ............................................................ 97

PredictionofCustomerBehavioronRFMTModelUsingArtifcialNeuralNetworks

Qeethara Kadhim Al-Shayea, Al-Zaytoonah, University of Jordan

Ghaleb Awad El-Refae, Al-Zaytoonah, University of Jordan ................................... 103

CHAPTER 6: CROSS CULTURAL COMMUNICATION ....................................... 109

A Research Model for Multilingual Electronic Meeting Systems

David Pumphrey, University of Mississippi

Milam Aiken, University of Mississippi

Mahesh Vanjani, Texas Southern University ............................................................. 110

v

Analysis of the Effectiveness of Corporate Responsibility as a PR Strategy

by Catalan Soccer Team Clubs

Xavier Ginesta, University of Vic

Enric Ordeix, Ramon Llull University ...................................................................... 116

WesternEuropesMystifcationofTurkeyandTheTurks

Raquel Casino, Independent Communications Professional ..................................... 122

CHAPTER 7: CROSS CULTURAL MARKETING ................................................... 128

Review of Culture and Materialism

Ziad Swaidan, University of Houston-Victoria ......................................................... 129

Problems of Counterfeit International Pharmaceutical Products

Branko Cavarkapa, Eastern Connecticut State University

Michael G. Harvey, University of Mississippi & Bond University (Australia) ........ 135

CHAPTER 8: ECONOMICS ......................................................................................... 142

Customers Demand Aversion to Polluting Product and Firms Output/Pricing Decision

Muhammad Rashid, University of New Brunswick

Basu Sharma, University of New Brunswick

Muhammad Jamal, Concordia University ................................................................. 143

P/E Ratio as a Market Timing Indicator for Twenty-Year Periods

Gary L. DeBauche, Drury University

Rodney A. Oglesby, Drury University ....................................................................... 149

CHAPTER 9: ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND SMALL BUSINESS ........................... 157

A Comparative Study on Native-Born and Foreign-Born Female Entrepreneurs:

A Narrative Approach

Chulguen (Charlie) Yang, Southern Connecticut State University

Margaret A. Goralski, Southern Connecticut State University .................................. 158

CHAPTER 10: ETHICAL AND SOCIAL ISSUES ........................................................ 164

Increasing Honor & Integrity in Classrooms: A Case Study

Amiee J. Shelton, Roger Williams University

Mary Concannnon, Roger Williams University ........................................................ 165

Toyota: An Example of Unethical Communication

Ashe Carolyn, University of Houston-Downtown .................................................... 171

vi

The First Step in Restoring Academic Integrity: Creating an ethical Guideline

Diane D. Galbraith - D.Ed. Slippery Rock University

Susan L. Lubinski - JD - Slippery Rock University .................................................. 177

American CEOs Perceptions of Suggested Strategies that Sustain Globalization

Marjorie G. Adams, Morgan State University

Abdalla F. Hagen, Wiley College .............................................................................. 183

CHAPTER 11: FINANCE ................................................................................................ 190

Valuing Distressed Private Companies: The Case of Furniture Manufacturing Company in Brazil

Ronald Jean Degen, International School of Management

K. Matthew Wong, St. Johns University .................................................................. 191

Stochastic Analysis of Margin Buying in Spain

Paloma Bernal Turnes, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

Jos Luis BeltrnVarandela, Universidad de Vigo

Irene GarridoValenzuela, Universidad de Vigo ......................................................... 197

CHAPTER 12: GLOBAL CORPORATE PR, SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

AND CULTURE ..................................................................................... 203

Public Relations Excellence In Spain: A Quantitative Analysis

Assumpci Huertas, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, (Taragona-Spain)

Enric Ordeix, Universitat Ramon Llull (Barcelona-Spain)

Natalia Lozano, Universitat Rovira i Virgili (Tarragona-Spain) ............................... 204

Management For Business Excellence: Public Relations Strategy

Rosa M. Torres, Alicante University ......................................................................... 210

The ABC (Argentina, Brazil, & Chile) Of Public Relations In Latin America

Macarena Urenda S, DuoUC Via del mar, Chile ..................................................... 217

Essentials of Managing Social Commitment As A Strategy To Establish Principles Of The

Organizational Culture

Enric Ordeix, Department of Communication-Ramon Llull University

Jordi Xifra, Department of Communication-Pompeu Fabra University ................... 223

News Tendencies In Political Communication: Lobbies & Think Tanks

Antonio Castillo Esparcia, University of Mlaga, Spain

Ana Almansa Martnez, University of Mlaga, Spain ............................................... 227

vii

CHAPTER 13: GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT AND TRENDS ....................................... 233

Revisiting Hofstedes Dimensions: The Evolving Cultures of the United States and Japan

Jonathan Wood, University of West Georgia

Christy Rabern, University of West Georgia

Jon Upson, University of West Georgia .................................................................... 234

From the Inside-Out: Internal Marketing and the Global Firm

Blaise J. Bergiel, University of West Georgia

Cheryl O. Brown, University of West Georgia

J Robert Field, Nicholls State University .................................................................. 240

Students Attitudes Towards Business Codes of Ethics: The Impact of Gender

Faramarz Parsa, University of West Georgia

Nabil Ibrahim, Augusta State University ................................................................... 246

The Evolution and Future of Cellular Telephony

KenGriffn,UniversityofCentralArkansas

Steven Zeltmann, University of Central Arkansas

Mark McMurtrey, University of Central Arkansas .................................................... 252

ShadesofGreen-ExploringVariousApproachestoGreenIT

Summer E. Bartczak, University of Central Arkansas

KenGriffn,UniversityofCentralArkansas

Steven Zeltmann, University of Central Arkansas .................................................... 257

CHAPTER 14: HUMAN RESOURCES MANAGEMENT .......................................... 263

Linkages between Perceived Occupational and Organizational Commitments of General

Employees in Japanese Organizations

Kaushik Choudhury, Reitaku University

Paul A. Fadil, University of North Florida ................................................................ 264

Application of a Medical Protocol to Worker Layoffs

C. W. Von Bergen, Southeastern Oklahoma State University ................................... 271

CHAPTER 15: INSTRUCTIONAL & PEDAGOGICAL ISSUES............................... 279

Clickers Technology Attitudinal Differences Of Native-Born And Immigrant Students:

What Are The Pedagogical Implications?

Kellye Jones, Clark Atlanta University ..................................................................... 280

viii

Clickers Technology Attitudes Of Business School Faculty: Outcomes, Evaluations

And Insights

Kellye Jones, Clark Atlanta University

Amiso M. George, Texas Christian University .......................................................... 287

Etextbook: A Framework to Understanding their Potential

Saurabh Gupta, University of North Florida

Charlene Gullett-Scaggs, University of North Florida .............................................. 294

One More Time: The Relationship Between Time Taken to Complete an Exam and

the Grade Received

James E. Weber, St. Cloud State University

Howard Bohnen, St. Cloud State University

James A. Smith, St. Cloud State University .............................................................. 301

Business Students Reported Perceptions of Faculty Consideration

Randall P. Bandura, Frostburg State University

Paul R. Lyons, Frostburg State University ................................................................ 307

Service Learning: Does It Change Student Perspectives?

Paula S. Weber, St. Cloud State University

Kenneth R. Schneider, St. Cloud State University

James E. Weber, St. Cloud State University .............................................................. 313

Using Classroom Exercises to Teach Sustainable Business and Strategic Communication

Writing in a Consumer Culture

Stevina U. Evuleocha, California State University

Amiso M. George, Texas Christian University .......................................................... 318

CHAPTER 1

ACCOUNTING HISTORY

1

THE CPA EXAMPAST AND FUTURE

P. Michael Moore, University of Central Arkansas

mikem@uca.edu

ABSTRACT

Fortune magazine once published a cover story proclaiming that modern society is

dependent on three great professions: medicine, law, and public accounting. A study of the

history of the accounting profession discloses that the development of a recognized designation

(CPA) which required a competency exam (CPA Exam) was an integral requirement for the

establishment of the profession. It is the CPA Exam which marks the birth of the profession in

the U.S. and it is the CPA examination which is the thread of continuity in the early development

of the profession. This paper reviews the history and development of the CPA examination from

its inception until the present with an overview of changes effective with the 2011 exam.

AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS

In the United States in the late 1800s, many public accountants were Chartered

Accountants who immigrated from England, Wales, and Scotland. The need for auditors and

public accountants grew as American commerce grew. As the number of accountants increased,

groups or societies were formed to discuss mutual problems and matters of interest. One such

group was the American Association of Public Accountants, later renamed the American

Institute of Certified Public Accountants, which was founded in New York in 1887 (Carey,

1969).

The primary leader of the organization was Edwin Guthrie, a Chartered Accountant from

London who was in New York for his firm. The model he promoted was that of the Institute of

Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (Edwards & Mirant, Jr., 1987). This organization

had started an entrance examination for Chartered Accountants in 1882 (Carey, 1969).

When the American Association was formed, there were no regulations governing public

accountants or auditors. The Association, desiring to upgrade the standing of the profession,

attempted to start a school of accountancy. In 1892 the Board of Regents of the University of

New York granted the Association a provisional charter for two years to operate the New York

School of Accounts. The school failed, but continued efforts by the Association were

instrumental in the passage of the first accounting law in the U.S. in 1896 (Edwards, 1960).

FIRST CPA LAW

On April 17, 1896, the Governor of New York signed into law "An Act to Regulate the

Profession of Public Accountants." This was the first legislation in the U.S. to use the

professional designation "Certified Public Accountant" (Edwards, 1960, p. 68). The law

prohibited anyone from using this title unless he had a certificate issued by the Regents of the

University of New York (Broaker & Chapman, 1978)

Under the New York law, the Regents of the University of New York were authorized to

make rules for examining prospective CPAs. In addition, the Regents were given the authority to

2

grant certificates by waiver for individuals who were practicing as public accountants at the time

the law was passed. A total of 126 certificates were issued by waivers in 1896 and 1897. None

were issued by examination. Certificate #1 was presented to Frank Broaker, who had made great

contributions in getting the first CPA law passed. It was not until 1898 that six certificates were

issued by examination (Edwards, 1960).

The law called for the CPA examination to be given each year in June and December.

The examination covered commercial law, theory of accounts, practical accounting, and auditing

(Webster, 1944). Each part was designed for a three-hour session. Candidates had to pass all four

subjects during a single examination to be certified. Candidates had to be at least 25 years old

and have three years of satisfactory experience in the practice of accounting in order to receive

the CPA certificate (Edwards, 1960).

THE FIRST CPA EXAM

The Regents appointed three prominent accountants as the Board of Examiners to

administer the first exam: Frank Broaker, Charles E. Sprague and Charles Waldo Haskins

(Edwards, 1960). The first CPA examination was given on December 15 and 16, 1896 in Buffalo

and New York City. The first session covered the theory of accounts; candidates were required to

answer five obligatory questions and were allowed to choose five of ten possible remaining

questions. Question number one asked the candidate to distinguish between the essential

principles of double-entry bookkeeping as opposed to single-entry. Other questions dealt with

distinguishing between accounts such as revenue account and trading account. Some questions

asked candidates to define various terms including fixed assets, cash, stock, capital, and loan

capital (Accountancy in the States, 1897).

The afternoon session tested the candidates in the area of practical accounting. This

section contained two obligatory questions. One required the candidates to prepare a statement of

affairs, and the other was a partnership problem. Also in the second session, the nominees had to

choose two of four questions covering the preparation of a balance sheet, partnership liquidation,

foreign exchange, or a joint venture problem.

The second day of the first CPA examination tested the candidates on auditing in the

morning session and commercial law in the afternoon. The subject matter of the auditing session

pertained to an auditor's duties, and the important areas of concern while auditing a corporation.

Next the questions turned to specific auditing procedures such as cash payments and receipts.

This section of the examination asked the applicants to answer five required questions and

choose five of seven other remaining questions. The fourth section covered commercial law.

Each of the four sections had 100 points possible, and a score of 75 on each section was

necessary for a passing mark (Accountancy in the States, 1897).

NEED FOR A UNIFORM EXAM

Other states followed New York's lead in passing CPA laws. Similar legislation was

passed by Pennsylvania in 1899; Maryland, 1900; California, 1901; Illinois, 1903; Washington,

1903; New Jersey, 1904; Florida, 1905; and Michigan, 1905. Thirty-one states had adopted CPA

laws by 1913 and all had such legislation by 1921 (Chatfield, 1968).

By the early 1900s the accounting profession in the United States had progressed, but it

was in need of a unifying factor which would enable it to be accepted and respected throughout

3

the nation. The development of a uniform CPA examination did more to satisfy that need than

any other factor.

As each state adopted CPA legislation, state boards of accountancy were set up. Because

each state prepared its own examinations, the difficulty and quality of the exams varied greatly.

In one state, CPA waiver certificates were granted to anyone who had bookkeeping experience

(Carey, 1969). The situation was described aptly in the following excerpt from an editorial by

Edward S. Meade in the July Journal of Accountancy, It has long been a reproach to the

Accountancy profession in the United States that the examinations proposed for admission into

the profession are exceedingly elementary and in no way comparable with the examinations for

admission into the other learned professions (Meade, 1915, p. 194).

Because accounting dealt with firms which conducted business across state lines, it was

recognized that the practice of accounting was largely of an interstate nature. However, since the

granting of CPA licenses was done on a state-by-state basis, many states were reluctant to grant

reciprocity to CPAs from other states. It was felt that only a national organization could provide

the leadership necessary to develop national standards. The American Association was national

but it had no authority over the individual state boards and could not dictate standards for them.

However, in 1916, the American Association was reorganized as the American Institute of

Accountants (now the AICPA) and new members could be admitted only after passing an

examination testing their technical competence and meeting experience requirements. A Board

of Examiners was selected to be responsible for the preparation and grading of the examinations

(Carey, 1969).

FIRST UNIFORM CPA EXAM

John F. Forest is credited with giving birth to the idea of a uniform examination for all

states (Carey, 1969). He suggested that since the Institute was going to prepare an examination

anyway, why not make it available to any of the states which wished to adopt it? This practice

would relieve individual states from the burden of preparing and grading an exam. If a candidate

passed the uniform examination given by the Institute, he could become a CPA in his home state

and a member of the American Institute, assuming he met the experience requirement (Menders,

1944).

The first uniform CPA examination was given in 1917 to 34 candidates from New

Hampshire, Oregon and Kansas (Menders, 1944). The examination consisted of auditing,

commercial law, theory and practices (two parts) and was administered over two days. A high

school education was required unless the Board granted waivers. The fee was $25 (Journal,

1916). All of the questions were either essay questions or long problems. There were no multiple

choice questions.

In order to participate in the program, cooperating states had to agree to administer the

exams simultaneously. The Board of Examiners insisted on grading the examinations in order for

the scores to count toward determining membership in the Institute (Uniformity of Examinations,

1917). By 1919, 22 states had adopted the Institute's examination as their own. It took thirty

years, however, before every state adopted the exam. During this period ten states quit using the

exam and later readopted it (Edwards, 1960).

National recognition of the CPA certificate was greatly facilitated by the widespread

adoption of the uniform examination. For example, certified public accountants were allowed to

enroll to practice before the U.S. Treasury without further examination. Before the adoption of

4

the uniform exam, such terms of enrollment were only available to lawyers. Reciprocity between

the state boards of accountancy was one of the most important contributions of the uniform

examination, because it promoted the practice of accounting on an interstate basis. Without such

a concession the accounting profession would not have developed to the extent it has today in

serving business and industry on a national and international basis (Menders, 1944).

EDUCATION REQUIRMENTS

The first exam given by New York in 1896 had no formal education requirement. With

the first uniform CPA exam in 1917, candidates were required to be a high school graduate. In

1939, New York became the first state to require a collegiate baccalaureate degree. Beginning in

1950, the AICPA lobbied states to require a college degree as the education requirement and

soon after most states made the adoption. In 1979, Florida passed legislation to require 150 hours

of college coursework in order to take the CPA exam. The 150 hour requirement went into effect

in 1983 in Florida. The AICPA and the National Association of State Boards of Accountancy

(NASBA) lobbied for all states to adopt the 150 hour requirement. By 2010, 47 states and

jurisdictions had adopted the 150 hour rule. The following five jurisdictions have not adopted the

150 hour rule: Colorado, Delaware, New Hampshire, Vermont, and the Virgin Islands. California

is the latest state to adopt; the rule goes into effect in 2014. There appears to be a trend to allow

candidates to take the exam after 120 hours of coursework, but to not be licensed without the 150

hours. Twenty-two states have adopted this model.

COMPOSITION OF THE EXAM

Beginning with the first uniform exam in 1917, the exam consisted of Theory and

Practice (two parts), Auditing and Business Law and was administered over two days. In 1942,

Theory was separated from Theory and Practice and the exam was given over two and one half

days. Practice consisted of two parts over two days but was assigned one grade. Major subject

topics appeared frequently, and minor topics were rotated in such a manner as to cover the entire

subject matter in a five year cycle. The difficulty of the exam was set at a level to test the ability

of a candidate to qualify as a senior accountant (Webster, 1943)

In 1994, the exam was reduced to two days again with the following parts, Financial; Tax

Managerial, and Governmental; Auditing; and Business Law. Since 1994, writing skills have

been graded; prior to that time they were not graded. Until 1996, CPA exams and unofficial

answers were published approximately three months after they were given. Since 1996, the

exams have been non-disclosed

The last major change in composition occurred in 2004 when the exam became

computer-based. The current parts are Financial Accounting and Reporting; Regulation;

Auditing; Business Environment and Concepts.

Until 2004, candidates were required to take all failed parts and in most jurisdictions had

to make a minimum of 50 on all parts in order to receive credit for any passed part. Since 1896

the passing score on every part has been 75. Beginning in 2004 with the introduction of

computed-based testing, candidates can take one part at a time.

5

TECHOLOGY CHANGES

Prior to 1994, no computation instruments, including slide rules, were allowed.

Beginning in 1994, four-function calculators were provided to candidates. In 2004, the currently

used computed based testing (CBT) system was introduced. For the first time, candidates take

the exam on a computer, can take the exam one part at a time, and can schedule to take any part

whenever they want tosubject to space availability and during eight specified months.

PASS RATES

There has been a noticeable increase in pass rates since the introduction of the computer-

based exam. For example, the pass rates for Auditing and Practice in 1985 was 31% and 34%. In

2009 the pass rates for Auditing and Financial Accounting and Reporting (FAR) was 50% and

49%. There are several explanations for the increased pass rates. Since the 150 hour requirement

has been adopted by most states, almost all candidates have had more accounting courses than

candidates taking the exam prior to the adoption of the 150 hour rule. With the adoption of CBT,

candidates can choose to take only one part at a time, thus their study preparation is

concentrated. Prior to 2004, candidates had to take and prepare for all failed sections. In many

states, a minimum grade of 50 was required in order to conditionally pass other parts, thus these

candidates had to prepare for all sections taken.

The passing score of 75 is not a percentage of correct answers. It is a score based on an

arbitrary decision as to what constitutes a minimum amount of knowledge and ability required to

function as a CPA. The AICPA can set the pass rate at any level. An examination of pass rates

for 30 years prior to 2004 indicates the pass rate on each part for each exam ranged from 30 to

35%. Beginning with the first CBT exam in 2004, the pass rates have increased approximately

50%. While the preceding paragraph provides two explanations for increased pass rates, the

author believes the AICPA may have arbitrarily increased pass rates to appease candidates who

have undertaken increased costs to meet the 150 hour requirement. If pass rates had not

increased, an argument could be made that the increased cost of more education fails to exceed

the benefits of that education.

Because of the changes in the exams administered in 2011, the AICPA has rescored the

75% threshold beginning with the 2011 exams. An increase in the number of candidates in the

fourth window of 2010 indicates that some believe the AICPA may decrease the percentage of

passing candidates in 2011.

EXPERIENCE REQUIREMENTS

Each state establishes its experience requirement to become a licensed CPA in that state.

These requirements range from very specific and carefully controlled requirements to general

and liberally interpreted requirements to none. In the early days of the profession, experience

was of extreme importance, because of the lack of courses in accounting offered in the schools.

As the education requirements to sit for the exam were increased, the experience requirement

became less important. The National Association of State Boards of Accountancy (NASBA) has

recommended that the experience requirement be one year. The trend has been to reduce or

eliminate the experience requirement as the 150 hours requirement has been adopted.

6

CHANGES IN 2011

The CPA exam has several changes in content and format beginning in 2011. The four

sections remain: Financial Accounting & Reporting (FAR), Auditing & Attestation (AUD),

Regulation (REG), and Business Environment & Concepts (BEC). For the first time the exam

will test an understanding of the FASB Codification and International Financial Reporting

Standards (IFRS). IFRS may be tested on all sections and the Codification will be tested on

research simulations. Operations management and strategic planning will be tested for the first

time in BEC. Also, ethics and professional responsibilities will be covered in AUD rather than

REG.

Historically, FAR, AUD, and REG have had two major simulations. Beginning in 2011,

the three sections will have 7 smaller task-based simulations. This will enable the examiners to

test more topics. There will be less emphasis on multiple choice questions and more on

simulations. The mix of multiple choice questions to simulations for FAR, AUD and REG have

been 70% to 30%. In 2011, the mix will be 60% to 40%. BEC will change from 100% multiple

choice to 85% multiple choice and 15% essay. Essay questions will be in BEC only.

CONCLUSION

Few professions have achieved the status and recognition enjoyed by public accounting.

The reason for the ascension to widespread public recognition is largely the result of the CPA

examination. The exam has provided a common denominator of entry level competence required

of all entrants into the profession. This common denominator has generally kept incompetents

out of the field and has established and maintained respect from every element in the business

community. Our laws require that corporations registered with the stock exchanges have to be

audited by a CPA. There are many other factors, of course, which have led to the development of

the public accounting profession; however, no other single factor has been more important in

contributing to the profession's growth than the CPA Examination.

REFERENCES

Accountancy in the States. (1897, January). The Accountant, 23, 52-56.

Broaker, F., & Chapman, R. M. (1978). The American Accountants Manual. New York: Arno

Press, p. 11.

Carey, J. L. (1969) The Rise of the Accounting Profession from Technical to Professional. New

York: AICPA.

Chatfield, M. (1968). Contemporary Studies in the Evolution of Accounting Thought. Belmont,

CA: Dickinson Publishing Co.

Edwards, J. D. (1960). History of Public Accounting in the United States. East Lansing, MI:

Michigan State University Business Studies.

Edwards, J. D., & Mirant, Jr., P. J. (1987, May). The AICPA: A Professional Institution in a

Dynamic society. Journal of Accountancy, pp. 22-41.

Meade, E. S. (1915, July). Established Preliminary Examinations in Law and Economics.

Journal of Accountancy, p. 194.

Menders, H. E. (1944, April). The Development of Uniform Examinations. The Accounting

Review, pp. 139-141.

Uniformity of Examinations. (1917, August). Journal of Accountancy, p. 54.

7

Webster, N. E. (1943, April). Planned Examinations. Journal of Accounting, p. 348.

Webster, N. E. (1944, April). Some Early Accountancy Examiners. Accounting Review, 135-139.

8

THE ANNUAL REPORT AND CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

Annette Hebble, TUI University

ahebble@tuiu.edu

Vinita Ramaswamy, University of St. Thomas

vinitar@stthom.edu

ABSTRACT

Certified Public Accountants (CPAs) have been involved with the preparation of

corporate annual reports since the inception of the profession. In addition to mandatory financial

reporting, we now hear calls for expanded corporate social responsibility reporting (CSR) from

various external groups. Should the two areas be combined into one report or kept separate? A

brief probe of the annual reports of 46 S&P100 companies indicates that integration is currently

limited. Some companies do include some CSR data in their annual report. What should be the

role of the CPA in any potential integration schemes?

INTRODUCTION

The annual report conveys not only financial information, but also serves as a corporate

communication tool aimed at various interest groups. The Web has speeded up the inclusion of

additional information in reports and new types of reports provided by companies. In spite of

continuous growth in sustainability reporting and a multitude of new reporting formats, the

annual report continues to serve as the main report to stakeholders. The document is typically

readily available on the corporate homepage for anyone interested. Trites (2008) confirms that

Web reports include additional topics, such as sustainability and governance, but the latter topics

are often covered in separate reports.

We typically associate annual reports with publicly held companies, but all types of

organizations issue these types of reports. Until the last decade, most reports were printed and

distributed to shareholders and other interested parties. The Annual Reports Library (n.d.) states

that the oldest printed annual report dates back to 1600, i.e. The Vatican's Annuarium

Statisticum.

THE PROFESSION

The first law creating the CPA designation was passed in New York in the year 1886

(Flesher, Previts & Flesher, 1996). The predecessor of the American Institute of Certified Public

Accountants (AICPA) was formed in 1887; a year after the New York law was passed (AICPA,

n.d.). Industrialization had a significant impact on our nation during the first part of the century

and its pace was accelerated after the Second World War. A changing economy, the passage of

the 1913 income tax legislation and the Securities Acts of 1933 and 1934 created an ever-

increasing need for the CPAs' skills. Since that time, the annual report has become a widely

distributed document including the basic financial statements and an attestation by the profession

(Dennis, 2000). It is probably fair to say that there is a strong association between the CPA

9

profession and the annual report. This is the case even though the annual report often includes

information beyond the traditional financial statements.

TRENDS

Stakeholders are demanding supplementary information apart from the traditional

financial statement. The International Federation of Accountants (IFAC, 2010) calls for a

narrative format in addition to the existing standardized format for financial information. Calls

for corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting are heard from various constituents. Triple

Bottom Line Accounting (TBL) is a term that has become synonymous with CSR reporting. John

Elkington (1997) first used this term to describe a report that would measure information on

financial, environmental and social aspects of periodic corporate progress. It is an approach that

enables organizations to measure and communicate its success on three separate dimensions. The

triple bottom line accounting model is not designed to replace, but rather to enhance and

supplement the information found in the financial statement.

A generally accepted format for triple bottom line reporting is the Global Reporting

Initiative's (GRI) G3 Guidelines. This non-profit organization provides transparent reporting

standards for a three-dimensional model of reporting. GRI provides rigorous standards and uses a

consensus-based approach for developing the criteria for inclusion. The standards can be used by

any size or type of organization regardless of origin. More than 800 organizations self reported

the use of GRI standards during 2010.

Other organizations are also implementing principles and standards for CSR reporting.

One example is The International Organization For Standardization (ISO), which implemented

its new voluntary social responsibility standard ISO 26000 on November 1, 2010. The United

Nations Global Compact (n.d.) is another effort to provide guiding principles for companies

wanting to act responsibly. The Global Compact consists of ten principles that cover human

rights, labour, environment and anti-corruption issues.

Another innovative approach to financial and sustainability reporting is recommended by

the IFAC. This international body recommends the use of a narrative approach to supplement the

traditional financial information and the need for new types of sustainability information (2010).

Additional information not easily disseminated within the traditional financial statements can be

captured using a narrative approach. The PricewaterhouseCoopers 2007 survey of the Fortune

Global 500 companies' narrative reporting found that companies adding narrative information to

explain performance and prospects provided superior reports. A narrative approach could also be

used to inform stakeholders of progress on sustainability related criteria. Such an approach may

shed additional light on the effect of sustainability efforts on corporate success and values.

CSR REPORTING

Porter and Kramer (2006) describe the potential benefits of CSR. Reporting additional

information can provide an opportunity for innovation and put the organization at a competitive

advantage. It should not simply be seen as a drain on corporate resources. Organizations who are

good corporate citizens are involved in shaping societal issues as opposed to merely distributing

funds to philanthropic causes. Every other year KPMG publishes a survey using public

information. It is considered one of the more comprehensive surveys available on this topic. The

2008 KPMG International Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting indicates that CSR

10

reporting is increasing, but the majority of such information is published in a separate report and

not as a part of the annual report. Further, it is established that CSR reporting is becoming the

norm instead of the exception for multinational corporations. Today, about 80 percent of the

large corporations include CSR in their reporting as opposed to only 50 percent three years ago

(KPMG, 2008, p. 2). More than three-quarters of the G250 and nearly 70 percent of the N100

use the GRI Guidelines for their reporting (KPMG, 2008, p. 4), which indicates significant

acceptance of this type of reporting by multinational corporations. Data from the survey leads

KPMG to predict that traditional financial report readers will increase the demand for

sustainability disclosures.

What is the role of accountants in TBL and CSR reporting as the demand for such

reporting continues to grow? Resources are limited, so people are trying to conserve resources,

increase efficiency, and identify and encourage those who are taking a lead. Markets, free

enterprise and competition determine whether a business is successful. This places a substantial

burden on the accounting profession to measure performance accurately and fairly on a timely

basis, so that scarce capital resources are effectively and efficiently allocated as investment

capital.

Does a relationship between sustainability reporting and financial reporting exist?

Sustainability reporting communicates a wide range of subject matter about environmental,

social and economic impacts arising from an entitys activities, products and services. Financial

reporting provides information about an entitys accountability for its monetary resources. But

both types of reporting communicate information about the entitys performance in creating

value for investors, the risks and other intangibles that affect valuation. The two types of

reporting can provide supplementary and complementary information so that the end user gets a

complete picture of the companys activities.

Starting in June of 2010 companies listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange will have

to integrate their sustainability reports with their annual reports (Temkin, 2010). South Africa is

among the first countries in the world to implement integrated reporting. Another country,

Denmark, already made a similar mandate in December of 2008 (Anonymous, 2009) for its

largest companies, public and private. It appears that Denmark was the first country to do so. The

Danish proposal suggests that a reputation as a socially responsible business community will also

make it more competitive on a global basis. An Indian proposal is more far reaching. This

proposal suggests that companies have to spend two percent of their average net profit and

disclose how the funds are spent in the annual report (Justmeans, 2010). These initiatives show

some actual examples of making sustainability information available as part of the annual report,

as suggested by the KPMG report.

REVIEW OF ANNUAL REPORTS

As we have noted, there are ongoing discussions and calls for integrated annual reporting.

In some cases, these trends are based on mandates. In other cases, the reporting is voluntary.

Currently, we have no mandate for integrated annual reports in the U.S. How are domestic

companies doing in this respect? S&P100 is an index that includes 100 multinational

corporations. Do S&P100 companies issue integrated annual reports? If not, what type of CSR

information do they include in the reports? We review a random sample of S&P100 corporate

annual reports to probe the current status of integrated reporting in the U.S. The list of S&P

companies was obtained from Mergent database.

11

In view of the current developments, this study examines the annual reports of the 46

randomly selected S&P100 companies. This analysis looks for information as to whether or not

these companies cover CSR activities in their annual reports. We scan the reports for references

to triple bottom-line accounting and CSR activities. Specifically, we look for certain terms that

fit into four categories that describe possible CSR activities. The CSR terms listed are included

in The A to Z of Corporate Social Responsibility (Visser, Matten, Pohl, & Tolhurst, 2008).

This comprehensive CSR guide lists and explains common CSR terms. The categories from

above and the terms for those categories are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

FOUR GROUPS OF COMMON CSR TERMS USED IN ANALYSIS OF ANNUAL REPORTS

Environment Community Ethics & Governance

Employee &

Consumer Concerns

Pollution Community Governance Consumer rights

Greenhouse Volunteer Code Product Stewardship

Carbon Donations Ethics Affirmative Action

Eco Public Relations Moral Responsibility Diversity

Environment Equal Opportunity

Gender issues

Health/Safety

We make no qualitative judgments or an attempt to rank the terms since the primary

interest was to determine whether or not the annual report is used to communicate CSR of

information. For each of term within a grouping, we count the number of occurrences in the

annual report to probe the coverage of these topics in the annual report.

ANALYSIS AND FINDINGS

The reports reviewed are those found on the companies' own websites. Once located, the

annual reports were scanned for the terms listed in Table 1. The number of occurrences for each

term was counted and recorded. Next, all occurrences within each group was added. The total,

maximum and minimum for each category are shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

INCIDENCE OF CSR TERMS FOUND IN ANNUAL REPORTS

Words from List Environment Community

Ethics &

Governance

Employee &

Consumer

Concerns

Total 1,145 204 1,099 197

Average 25.44 4.53 24.44 4.66

Maximum 154 21 323 54

Minimum 0 0 0 0

All annual reports did not follow the same format. Today, some companies still provide a

traditional thick annual report with a lot of corporate data in addition to the financial statements.

12

Others only provided the 10-K with a few introductory pages. We treat all the reports, regardless

of format in the same manner for purpose of this analysis.

Table 2 shows that environmental topics are most commonly discussed in the annual

reports. Ethics and governance issues come in a close second. However, some of the companies

discussing the latter topics put a lot of emphasis on it as evidenced by a maximum of 323 words

by one organization. As a contrast, the companies with the most emphasis on the environment

only used 154 of the listed terms. Some companies did not include these terms at all in their

annual reports. It may be mentioned here that environmental and governance disclosures are

mandatory for most companies. Issues pertaining to the community, and employee and consumer

concerns receive much less attention. The average of terms included for the latter categories was

about one fifth of the average for environmental and, governance and ethics concerns.

SUMMARY

The analysis of a sample of annual reports does show limited inclusion of overall CSR

concerns and are limited to those of the environment, and governance and ethics. The idea of

integrated reporting dates back to Elkington's call for Triple Bottom Line Accounting in 1997. At

this point in time our brief probe indicates that integration is not the norm. New calls for

integration are emerging. One example is the report put forth by Lydenburg, Rogers & Wood

(June, 2010) from The Hauser Center for Non-Profit Organizations at Harvard University.

Previously, we have noted that such integration is mandated in Denmark and on the

Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

U.S. accountants who have hereto been the main purveyors of information about a company can

take a leading role in this emerging field by providing advisory services on developing systems

and strategies, certification of environmental and employee friendly policies, due diligence

services, benchmarking and assurance services. There are however some milestones that should

be accomplished before public accountants can provide such services such as (i) development of

generally accepted criteria for sustainability reporting (ii) setting up information systems to

gather necessary data (iii) sufficient knowledge and expertise on the part of accountants (iv) a

well developed marketing strategy for accountants to position themselves as providers of

assurance services. Accountants may then be able to integrate all sources of information about a

company (both financial and non-financial) into one set of reports.

REFERENCES

American Institute of CPAs, (nd). AICPA Mission and History. Retrieved from

www.aicpa.org/about/missionandhistory/Pages/MissionHistory.aspx

Anonymous. (2009, February). Enviromation, 55; 474.

The Annual Reports Library (n.d.). Trivia from the Annual Reports Library. Retrieved from

www.zpub.com/sf/arl/arl-triv.html

Dennis, A. (2000, June 1), No One Stands Still In Public Accounting. Journal of Accountancy.

Retrieved from www.allbusiness.com/accounting/565228-1.html

Elkington, J. (1997) Cannibals with forks: the triple bottom line of the 21

st

century business.

Capstone, Oxford.

Flesher, D., Previts, G., & Flesher, T. (1996). Profiling the New Professional Industrials: The

First CPAs of 1896-97 Business and Economic History, 25(1), 252-66.

13

Global Reporting Initiative. (2010, September 25). GRI List Who is reporting? Retrieved from

www.globalreporting.org/ReportServices/GRIReportsList/

Lydenburg, S., Rogers, J., & Wood, D. (June, 2010). From Transparency to Performance:

Industry-Based Reporting on Sustainability Issues. The Hauser Center for Non-Profit

Organizations at Harvard University. Retrieved from hausercenter.org/iri/wp-

content/uploads/2010/05/IRI_Transparency-to-Performance.pdf

International Federation of Accountants (2010). Enhanced Transparency Using Narrative

Reporting. Retrieved from web.ifac.org/sustainability-framework/ip-enhhanced-

transparency-reporting

International Organization for Standardization. (2010, October 29). 1 November launch of

ISO26000 guidance standard on social responsibility. Retrieved from

www.iso.org/iso/pressrelease.htm?refid=Ref1366

Justmeans. (2010, August 16). Indian industries oppose mandatory CSR reporting. Retrieved

from www.justmeans.com/Indian-industries-oppose-mandatory-CSR-

reporting/26759.html

KPMG. (2008). KPMG International Survey of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting 2008.

Retrieved from

www.kpmg.com/LU/en/IssuesAndInsights/Articlespublications/Pages/KPMGInternation

alSurveyonCorporateResponsibilityReporting2008.aspx

Mergent Online. (2010, September 29). Houston Public Library, Houston, TX. Retrieved from

www.mergentonline.com/compsearch.asp

Porter, M., & Kramer, M. (2006). Strategy and Society. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved

from www.globalcompactnamibia.org/pdf/CSR%20-%20Porter%20Kramer%20-

%20CSR%20along%20the%20value%20chain.pdf

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2007). A survey of the Fortune 500 Global Companies' Narrative

Reporting. Retrieved from www.pwc.com/gx/en/corporate-reporting-services/fortune-

global-500-companies-survey.jhtml

Temkin, S. (2010). Annual Report Must Include Sustainability. Business Day.

Trites, G. (2008, September). Corporate reporting on the Web. CA magazine, 141(7), 16-17.

Retrieved from ABI/INFORM Global, (Document ID: 1554991541).

United Nations Global Compact. (n.d.) The Ten Principles. Retrieved from

http://www.unglobalcompact.org/aboutthegc/thetenprinciples/index.html

Vissser, W., Matten, D., Pohl, M., & Tolhurst, N., eds. (2008). The A to Z of Corporate Social

Responsibility: The Complete Reference of Concepts, Codes and Organisations. West

Sussex, England: Wiley.

14

CHAPTER 2

ADVERTISING AND MARKETING COMMUNICATION

15

SOCIAL NETWORKS - THE DARK SIDE

Hy Sockel, DIKW Management Group

hysockel@yahoo.com

Louis K. Falk, University of Texas at Brownsville

Louis.Falk@utb.edu

ABSTRACT

Social Networking has become phenomenally popular over the last few years. The uses

have run from business applications (where various expertise have been shared), to private

individuals using Social Networking within a group of friends. As with any new form of

communication there are many issues that need to be addressed for this medium to be completely

successful. As the masses began to utilize Social Networking - unintended consequences were

realized. This paper explores the uses of Social Networking, the unplanned issues associated

with it, and possible solutions on how to manage Social Networking.

INTRODUCTION

While the Internet had its humble beginning in the United States, it is a global

phenomenon that is not limited to any one country or region. It has become a platform of

communication, commerce, and community. The social aspects of the Internet are notorious. The

public is tuned in to the scale and access for both the beneficial and the harmful (and

inappropriate) side of online content. There are websites dedicated to a variety of what one

would call anti-social behavior: terrorism, bomb building, criminal hacking, drugs, sex

It should be no surprise that the Internet causes passionate discussion as it relates to

threats and opportunities, particularly for the young. The Internet is not limited to any particular

age group. In a recent study for the United Kingdom (UK) Parliaments Office of

Communications (OFCOM), face-to-face computer aided interviews were held with 653 parents,

653 children (aged 5-17 years from the same household), and 279 non-parents. OFCOM key

findings are: (UK Parliament OFCOM report, 2008).

The Internet is used and valued by children and parents as well as the non-parent

adults.

Overall, 99% of children aged 8-17 say that they use the Internet,

80% of households with children aged 5-17 have Internet access at home (compared

to 57% of households without children).

TV remains the dominant medium for children aged 5-15,

The use and importance of the Internet to the child increases with age both in terms of

hours of use and in its status as the medium the child would miss the most.

The average hours of use of the Internet by children has increased greatly over the

past two years (from 7.1 hours/week in 2005 to 13.8 hours/week in 2007 for 12-15-

year-olds).

Almost two-thirds of the population is online,

16

Overall, 16% of children have a computer with Internet access in their bedroom (a

rise from 1% of 5-7-year-olds, to 12% of 8-11-year-olds and 24% of 12-17-year-

olds); parents also tend to underestimate their child's access to the Internet at a

friend's house.

Over the years, the Internet has gradually grown from being a tool used mainly by

scientists and academics to one of people and commerce. This was not a radical change in web

technologies but rather results of cumulative changes in the ways software developers and end-

users use the Web (Sockel and Falk, 2010). Social networks are a byproduct of the Internet and

the World Wide Webs new horizons.

WEB 2.0

The term Web 2.0 describes the range of user-controlled publishing and networking

websites that have emerged over the past five years, allowing people greater connectivity,

autonomy, and voice in online activities. This capability stands in contrast to older, less

interactive, what one might call Web 1.0 sites that limit users to passive viewing and

information retrieval and whose content only the sites owners could modify (OReilly, 2005).

With the newer approach, there is an embodied blurring of the boundaries between Web users

and producers, consumption and participation, authority and amateurism, play and work, data

and the network, reality and virtual-reality (Zimmer, 2008, p. 1).

User generated web content, such as blogs, wikis, social networking sites, and RSS (real

simple syndication) feeds, are rapidly creeping into a large percentage of organizations, offering

suppliers, employees, customers, and users new ways to collaborate and communicate. Gartner

Inc. of Stamford, Connecticut estimates that the size of the enterprise social software market will

triple; growing from $317.5 million in worldwide sales in 2007 to $939.4 million in 2012.

The nature of these increasingly interactive participative environments enrich the users

experience and contribute to Web 2.0 ecology which includes social networking, media sharing

and manipulation sites, data/web mashups, conversational arenas, virtual worlds, social

bookmarking, blogs, wikis, and other collaborative editing sites (Crook, 2008).

SOCIAL MEDIA

More people are using the social media for entertainment, escape, work, keeping up with

friends, looking for work, researching issues, dating, and general communications. Facebook,

Twitter, LinkedIn, Blogs, MySpace, YouTube, Flickr, Wikipedia and others are all part of what

is now known as social media. Social media provide new innovative means for people to

communicate.

What differentiates a social networking site from the run of the mill typical Web site?

CareerBuilder (2009) indicates that a typical website is controlled by a small group of

individuals (or perhaps just one person) with centralized control, for the purpose of simply

pushing out information; while social networking sites invite users to contribute to the content.

In true social media, much of the content comes from the public. Users become active members,

by contributing content, and suddenly have a stake in the success of the site.

However, being a content provider, posting opinions, asking questions can come with

risks. Oftentimes the site literally mines the data provided to create media data databases that

contain enormous amounts of information about individuals, in addition to the persons name,

17

address and other contact data. They often contain much more personal information such as

where one lives, age, specific areas of interest, and even photos.

PC Tools Newsletter (2010) indicates that 32% of social network users are willing to put

themselves at risk. Some Web users will sit in front of their computer for hours and will get into

a state known as the flow totally losing track of what is happening. People in the flow state

can make poor decisions, for example: too much personal data may be volunteered online,

without considering the repercussions of this action. This has the potential of making the

criminals job easier. Things people would not tell a close friend end up being shared with the

whole world.

The Social Network Phenomena

Thanks to the global popularity of social networking an estimated 600 million people

have personal online profiles friends, prospective employers and enemies alike are able to

access photographs, videos and blogs that may have been long forgotten with a few simple clicks

of a mouse (Taylor, 2010). Many organizations are concerned about employees wasting time,

playing games, doing personal things on such sites. Some organizations have considered

blocking access to these sites altogether. Social networks play an important role for an

organization as part of their routine business practices. CareerBuilder (2009) points out that from

grocery stores to alumni associations, and even the local hair salon, nearly every type of

organization today is finding a way to market its business, products, and services using social

networking sites or what is now most commonly referred to as simply social media. Basically, by

encouraging interaction among users, these sites create an interactive experience that users do

not get from a typical Web site.

What is Social media?

Charlene Li and Josh Bernoff, in their book Groundswell: Winning in a World

Transformed by Social Technologies, describe social networking as a social trend in which

people use technologies to get the things they need from each other, rather than from traditional

institutions like corporations (CareerBuilder, 2009, p. 5).

CareerBuilder goes on to indicate that

People are central to social media and its success

They are the creators and the drivers of the platform, and

Organizations that successfully use social media understand how to use this space to

interact with users on a personal level (CareerBuilder, 2009, p. 7).

Facebook

Facebook (2010) says it is a social utility that helps people communicate more

efficiently with their friends, families and coworkers (p. 2). It further states on its website that it

develops technologies that facilitate the sharing of information through the social graph, the

digital mapping of people's real-world social connections. Anyone can sign up for Facebook and

interact with the people they know in a trusted environment. As the second most trafficked Web

site in the world, Facebook claims to have more than 400 million active users, of which 50% log

on to Facebook on any given day. Withers (2008) indicates That the soaring popularity of social

networking sites such as Facebook and MySpace underlines how attitudes towards privacy and

information-sharing are changing, especially among the younger generation (p. 17)

18

This type of social networking site indicates that it has over 900 million objects that

people can interact with (pages, groups, events and community pages). Additionally, this type of

site claims that there are more than 30 billion pieces of content (web links, news stories, blog

posts, notes, photo albums, etc.) shared each month (Facebook, 2010).

Twitter

According to Twitter.com/, Twitter is a real-time information network powered by people

all around the world that lets them share information. Twitter tries to answer a simple question

whats happening now? It does this by allowing users to send and receive very short messages

called tweets. A tweet can be a maximum of 140 characters. Twitter was launched in 2008 as a

free micro-blogging site that enables users to maintain a web log (blog). Its popularity has grown

exponentially; it now has more than 17 million registered users.

LinkedIn

LinkedIn is a free professional networking site that enables members to post their

resumes, recommendations from friends, and to connect with other industry professionals. With

over 53 million members in over 200 countries and territories around the world LinkedIn is a

powerful resource for those that need help with employment. According to a LinkedIn site search

(conducted December 1, 2010) a new member joins every second of every day.

Blogs

Blogs are an acronym form Web Log, in this regard it can be viewed as a multiuser or a

participatory diary. Blogs have at least one owner, but many have several commentators

contributing to site content. Its success is typically measured by the number of (unique) readers,

and by its ability to generate meaningful reader comments, as well as links from other blogs and

Web sites.

RISK FACTORS

Security

While there are many security issues using social media a few stand out and can be

applied across the medium. According to a Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Announcement

posted at blog.twitter.com, there have been two different security incidents concerning Twitter.

In January and April 2009, these breaches affected a total of 55 accounts - public and nonpublic

information was accessible and at least one users password was reset.

Anthony Bettini of McAfee (2010) points out that much of the increased ability for

attackers to plague the general public is due to decreased privacy in combination with enhanced

desire to use web enable devices. In a relatively new use of this technology (in an attempt to

make the reservation check process more palatable) many restaurants have adopted wireless

applications such as Foursquare and Twitter based services for allowing patrons to check in. In

affect the consumers via Foursquare/Twitter were publicly broadcasting that they were not home.

Posting of personal information is another issue. Sites like LinkedIn encourage

individuals to post resumes online. Many different organizations warn users not to be too

flamboyant when it comes to posting a resume on a public site like LinkedIn; keep in mind that

your profile can be seen by everyone - including your current boss, discretion is encourage at all

times.

19

Online social networks, perhaps because of the ambiguity and lack of transparency, can

be infested with malware such as: Trojans, Viruses, Worms, and Key-loggers. Security incidents

are rising at an alarming rate every year. As the complexity of the threats increases, so do the

security measures required to protect networks. Being careful is no longer enough. Malware has

gone from the days of ego based individuals creating havoc just to see how the news reports it, to

those that are only thinking of the dollar $igns. A relatively new threat in malicious software is

known as drive-by Malware. Drive-by infects a machine just by landing on a web site. The

problem is that while the cyber world has become more dangerous, the impetus to get online has

gotten stronger.

Addiction

Within the mental health community there is a debate whether or not individuals are

using the Internet too much, too often, and for too long. Today, Web surfing has become a social

pastime and has taken the place of other activities such as bar hopping or going to the movies. As

the web has become a part of mainstream life, some mental health professionals have noted that

a high percentage of people are using the web in a compulsive and out-of-control manner. They

purport that the Internet usage for some individuals exhibit the characteristics of addiction. In a

true addiction, a person becomes compulsively dependent upon a particular kind of stimulation

to the point where obtaining a steady supply of that stimulation becomes the sole and central

focus of their lives. In a true addiction the addicts increasingly neglect work duties,

relationships, and ultimately even health in the drive to remain stimulated (Bursten &

Dombeck, 2004, para. 2).

CONCLUSION

Eric Schmidt, the chief executive, who alongside the founders Sergey Brin and Larry

Page runs Google, the world's largest search engine company told the Wall Street Journal

that he doesnt believe that society understands the ramifications of having huge amounts of

information available, knowable and recorded by everyone all the time. Schmidt issued a stark

warning over the amount of personal data that people post on the Internet. He states that

someday many of them will be forced to change their names and identity in order to escape their

cyber past. His statements have sparked debate on the sheer amount of information we give away

about ourselves online and how most of that data is virtually un-erasable (Taylor, 2010).

In an article discussing privacy concerns generated by Google's data mining capabilities,

CNet's reporters published Mr. Schmidt's salary, named the neighborhood where he lives, some

of his hobbies and political donations. All the information had been gleaned from Google

searches (Taylor, 2010).

REFERENCES

Bettini, A. (2010). Social Networking Apps Pose Surprising Security Challenges. McAfee

Labs; White Paper Social Networking Apps Pose Surprising Security Challenges;

Retrieved from

http://www.digitaleragroup.com/component/rokdownloads/downloads/mcafee/169-

social-networking-apps-challenges/download.html

20

Bursten, J., & Dombeck, M. (2004, Apr 16). Introduction to Internet Addiction. Mentalhelp.Net

Internet Addiction and Media Issues; Retrieved from

http://www.mentalhelp.net/poc/view_doc.php?type=doc&id=3830

CareerBuilder (2009). Logging on: What is Social Media? Retrieved from

http://www.careerbuildercommunications.com/pdf/socialmedia.pdf

Crook, C. (2008). Web 2.0 Technologies for Learning: The Current Landscape - Opportunities,

Challenges and Tensions. Retrieved from http://partners.becta.org.uk/upload-

dir/downloads/page_documents/research/web2_technologies_learning.pdf

Facebook (2010, August). Retrieved from http://www.facebook.com/press/info.php

LinkedIn (2010). Retrieved from http://press.linkedin.com/about/

O'Reilly, T. (2005, September 30). What is Web 2.0: Design patterns and business models for

the next generation of software. Retrieved from

http://www.oreillynet.com/pub/a/oreilly/tim/news/2005/09/30/what-is-web-20.html

PC Tools Newsletter (2010, August 22). Retrieved from

http://www.pctools.com/news/view/id/283/

Sockel, H., & Falk, L. K. (2010). Social Networking - Whats In It for Me? American Society of

Competitiveness Presentation; Washington, D.C. October 2009.

Taylor, J. (2010 Aug 18). Google Chief My Fears for Generation Facebook. Retrieved from

http://license.icopyright.net/user/viewFreeUse.act?fuid=OTU3NTg3Mg%3D%3D

UK Parliament OFCOM report (2008 July 31) Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport