Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

2007 Clayton

Загружено:

Sami IslamАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

2007 Clayton

Загружено:

Sami IslamАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

OFF SITE MANUFACTURE AND MODULAR CONSTRUCTION THE FUTURE OF HOUSE BUILDING?

submitted by William Clayton

for the MSc in Quantity Surveying

at London South Bank University

Faculty of Engineering, Science and Built Environment

Department of Property, Surveying and Construction

year 2007

Restrictions on use

This dissertation may be made available for consultation within London South Bank University and may be photocopied or lent to other libraries for the purposes of clarification.

Signed:

William Clayton

(William Clayton)

Authors declaration

I declare that this dissertation is my own unaided work except where specifically referenced to the work of others.

Signed:

William Clayton

(William Clayton)

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the following people for their support and assistance during the course of undertaking this dissertation:

Ben Kennedy Marketing Project Manager, Urban Splash

Gordon Callaway Group Policy Manager, Hyde Housing Association

Susan May Principal Development Manager, The Peabody Trust.

Keith Tweedy Senior Lecturer, London South Bank University

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Contents

CONTENTS Page

Contents

List of Tables and Figures

Abstract

10

Introduction 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Scope of Chapter Rationale Aim Objectives Research Questions Assumptions Outline Methodology Dissertation Structure Chapter Appraisal 11 11 13 13 13 14 15 16 17

Off-site manufacture A History in Construction 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Scope of Chapter Definition of the Terms Origins of Off-site manufacture in the United Kingdom 1914 1939 1939 onwards Large-panel high-rise residential buildings 2.6.1 2.6.2 2.7 2.8 Ronan Point, Newham, East London Other problems with high-rise LPS systems 18 18 21 22 23 24 25 25 27 27 27 28 30

Non-Domestic Applications Policy Agenda 2.8.1 2.8.2 The Latham Report The Egan Report

2.9

Chapter Appraisal

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Contents

Page 3 Off-site manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Scope of Chapter The Current Situation Benefits of Off-site manufacture Barriers to Application 3.4.1 3.4.2 3.4.3 3.4.4 3.4.5 3.4.6 3.5 3.6 General Image Perceived Performance Customer Expectation Perceived Value Industry Culture Product Awareness 31 31 33 35 35 35 36 36 37 37 38 39

Applications for Future Use Chapter Appraisal

Successful Projects Using Off-site Manufacture 4.1 4.2 Scope of Chapter Successful Projects using Off-site Manufacture 4.2.1 4.2.2 4.2.3 4.2.4 4.2.5 4.3 Moho Urban Splash Barling Court Hyde Housing Association Corbet House Hyde Housing Association Murray Grove The Peabody Trust Barons Court The Peabody Trust 41 41 42 43 45 47 49 51

Chapter Appraisal

Research Design and Methodology 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Scope of Chapter Statement of Research Aim Research Strategy Rationale of the Research Questionnaire Rationale of the Interviews The Research Sample Method of Analysis 53 53 54 55 59 61 62

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Contents

Page 5.8 Chapter Appraisal 62

Data Analysis and Results Detailed Analysis 6.1 6.2 6.3 Scope of Chapter Detailed Analysis Moho Urban Splash Detailed Analysis Barling Court Hyde Housing Association 6.4 Detailed Analysis Corbet House Hyde Housing Association 6.5 Detailed Analysis Murray Grove The Peabody Trust 6.6 Detailed Analysis Barons Place The Peabody Trust 6.7 Chapter Appraisal 101 94 88 81 64 64 74

Data Analysis and Results Benchmarking 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Scope of Chapter Benchmarking Key Performance Indicators Assessment of the Construction Programme Assessment of the Construction Costs Chapter Appraisal 102 102 112 114 116

Conclusions and Recommendations 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Scope of Chapter Limitations Research Questions / Objectives Summary of Key Findings / Recommendations 118 118 120 122

References

124

Appendix 1 Appendix 2 Appendix 3 Appendix 4

Blank Questionnaire Questionnaire Response from Urban Splash Questionnaire Response from Hyde Housing Association Questionnaire Response from The Peabody Trust

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Contents

Appendix 5 Appendix 6

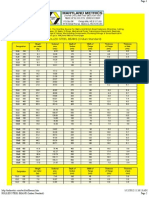

Variables Affecting BCIS Estimated Construction Time Variables Affecting BCIS Average Prices

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) List of Tables and Figures

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

Tables

Page

Table 6.2.1

Comparison of Construction Cost and Programme for the Moho development

73

Table 6.3.1

Comparison of Construction Cost and Programme for the Barling Court development

81

Table 6.4.1

Comparison of Construction Cost and Programme for the Corbet House development

87

Table 6.5.1

Comparison of Construction Cost and Programme for the Murray Grove development

94

Table 6.6.1

Comparison of Construction Cost and Programme for the Barons Place development

101

Table 7.3.1

Variables affecting the BCIS Estimated Construction Time

113

Table 7.4.1

Variables affecting the BCIS Mean Construction Cost

115

Figures Figure 1 Off-site Manufacture and its related techniques 21

Figure 4.1 Figure 4.2

Urban Splashs Moho Development Hyde Housing Associations Barling Court Development

42 44

Figure 4.3

Hyde Housing Associations Corbet House Development

46

Figure 4.4 Figure 4.5

The Peabody Trusts Murray Grove Development The Peabody Trusts Barons Place Development

48 50

Figure 6.2.1 Figure 6.2.2 Figure 6.2.3 Figure 6.2.4

Moho location plan Construction of a unit at the Moho Development Computer generated image of a completed unit Significant factors in choosing modular construction for the Moho project

65 66 66 68

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) List of Tables and Figures

Page Figure 6.2.5 Benefits of off-site manufacture and their significance to the Moho project Figure 6.2.6 Figure 6.2.7 Figure 6.2.8 The Moho modules under construction in the factory A completed Moho unit Barriers to adoption of off-site construction and their affect on the Moho project 70 70 72 69

Figure 6.3.1 Figure 6.3.2 Figure 6.3.3

Barling Court location plan Barling Court Typical Floor Plan Significant factors in choosing modular construction for the Barling Court project

74 75 76

Figure 6.3.4 Figure 6.3.5

The exterior of Barling Court Benefits of off-site manufacture and their significance to the Barling Court project

78 79

Figure 6.3.6

Barriers to adoption of off-site construction and their affect on the Barling Court project

80

Figure 6.4.1 Figure 6.4.2 Figure 6.4.3

Corbet House location plan Diagrammatic construction of the BUMA system Significant factors in choosing modular construction for the Corbet House project

82 83 84

Figure 6.4.4

Benefits of off-site manufacture and their significance to the Corbet House project

85

Figure 6.4.5 Figure 6.4.6

A typical bathroom at the Corbet House development Barriers to adoption of off-site construction and their affect on the Corbet House project

86 86

Figure 6.5.1 Figure 6.5.2 Figure 6.5.3

Murray Grove location plan The stacking style construction of Murray Grove Significant factors in choosing modular construction for the Murray Grove project

88 90 90

Figure 6.5.4

Benefits of off-site manufacture and their significance to the Murray Grove project

91

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) List of Tables and Figures

Page Figure 6.5.5 Barriers to adoption of off-site construction and their affect on the Murray Grove project Figure 6.5.6 The Murray Grove development 93 92

Figure 6.6.1 Figure 6.6.2

Barons Place location plan Significant factors in choosing modular construction for the Barons Place project

95 97

Figure 6.6.3

Benefits of off-site manufacture and their significance to the Barons Place project

98

Figure 6.6.4 Figure 6.6.5

The interior quality at Barons Place Barriers to adoption of off-site construction and their affect on the Barons Place project

99 100

Figure 7.2.1 Figure 7.2.2

KPI results for Urban Splash and the Moho development KPI results for Hyde Housing Association and the Barling Court and Corbet House developments

104 105

Figure 7.2.3

KPI results for The Peabody Trust and the Murray Grove and Barons Place developments

106

Figure 7.2.4

KPI Comparison of all developments with Construction Industry data for 2006 Client Satisfaction (Product)

108

Figure 7.2.5

KPI Comparison of all developments with Construction Industry data for 2006 Client Satisfaction (Service)

109

Figure 7.2.6

KPI Comparison of all developments with Construction Industry data for 2006 Defects

111

Figure 7.3.1

Comparison of Construction Programme for all projects

112

Figure 7.4.1

Comparison of Construction Costs for all projects

115

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Abstract

ABSTRACT

Off-site manufacture has been used in the construction industry for over 100 years, and as such, the benefits are both numerous and widely known. However, take-up in the housing sector, in the form of modular construction, has been much slower. Through detailed case study research, this work seeks to understand why this is the case, and whether these benefits can be transferred into the house building process, to help meet the current demand for new homes.

Three client organisations that have used modular construction recently with apparent success have been investigated as part of the research. By way of an initial postal questionnaire and follow up semi structured interview, each organisations perception and attitude towards modular construction, along with their principles of best practice have been examined and analysed.

This has led to a number of interesting conclusions being drawn. For example, modular construction will produce a better quality finished product, as well as significant savings in terms of the construction programme, when compared to traditional building methods. Furthermore, the research has suggested that those clients who procure using modular construction will be more satisfied as a result,

The schemes reviewed have proved to be a great success in the marketplace. This has led the author to feel that through careful planning and systematic implementation, off-site manufacture through modular construction is the future of house building.

10

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

If the industry is to achieve its full potential, substantial changes in the culture and structure are required to enable the improvements in the project process that will deliver our ambition of a modern construction industry Sir John Egan

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

1.1

Scope of Chapter

This opening chapter will set out the rationale, aim and principal objectives of the dissertation. It will also outline certain research questions that need to be

answered, and assumptions that have had to be made, in an attempt to prove the aim and meet the objectives of the study.

Furthermore, a diagrammatic outline to the research methodology will be presented and the structure of each subsequent chapter will be briefly described.

By the end of the chapter, a clear understanding of the reason for choosing the subject area, as well as the structure of the study, will have been presented.

1.2

Rationale

Construction needs to increase its use of off-site methods (Building, 2005a). That claim came seven years after the publication of the Construction Task Forces Report, Rethinking Construction (The Egan Report). This called for the industry to industrialise and modernise in order to meet the changing needs and objectives of its clients.

Why then, a considerable time since the Egan Report, and over a decade since Sir Michael Lathams Constructing the Team, is the industry still being urged to adopt more off-site manufacture? Both knights recommended it as a way of increasing efficiency and, while the situation cannot change overnight, why has takeup been so limited?

Don Ward, deputy chief executive of Constructing Excellence in the Built Environment, has offered a possible explanation. He feels that the problem is

caused by a catch-22 situation, with the supply chain and clients both being

11

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 1 Introduction

reluctant to make the first move towards mass use of the method (Building, 2005a). As a result, take-up is not happening widely enough to lower unit costs.

This is clear with the large speculative house builders the sector of the industry that offers the most practical source of off-site manufacture, due to the standard range of products that they construct. The biggest players have generally failed to advocate these methods. In contrast, smaller, trendier developers such as Manchester-based, Urban Splash, and forward thinking Housing Associations, such as Hyde and The Peabody Trust have adopted them and, consequently, reaped the benefits.

Urban Splash pioneered the UKs first private-sector, multi-storey housing development to be based on prefabricated volumetric modules. The 102-flat, Moho development, just west of Manchester city centre, designed for young graduates and key workers, has gained high recognition. Its volumetric manufacturer, Yorkon, also won Building Magazines Off-site Specialist of the Year 2005 (Building, 2005b).

Meanwhile, in constructing Barling Court, in south-west London, Hyde Housing Association has built a four-storey key-worker apartment block, which is claimed to have taken 14 months less to build than similar traditional developments (Spring, 2004a), and reputedly worked out at 210,000 cheaper than a standard prefabricated solution. In addition, the Peabody Trusts Murray Grove, in east

London, was the first multi-storey housing project in the UK to be entirely factory built.

Through detailed case study research, the dissertation will analyse and evaluate the processes and procedures adopted by the organisations claiming to maximise the benefits of off-site manufacture. Examples will be drawn from the

private development sector, and the social housing market. Ultimately, suggestions for best practice will be made. It is hoped that these can then help to identify which off-site procedures could be adopted by the larger house builders to assist in meeting the Deputy Prime Ministers target of new housing over the coming years, thus proving that off-site manufacture has a key role to play in the future of house building.

12

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 1 Introduction

1.3

Aim

To prove that off-site manufacture and modular construction is significant in the construction industry and, consequently, the future of house building in order to help meet current housing demand.

1.4

Objectives

The study has four key objectives, namely:

1.

To identify the various techniques of off-site manufacture used by each of the organisations.

2.

To highlight the benefits that those techniques bring to the relevant projects and their clients.

3.

To identify the areas in which the large speculative house builders should use off-site manufacture to improve their efficiency and effectiveness, and meet government housing targets.

4.

To show that modular construction has a significant place within the construction industry in helping to meet housing demand.

1.5

Research Questions

In order to meet the aim and key objectives of the study, it is necessary to answer a number of key research questions. These are:

1.

What specific techniques of off-site manufacture do the organisations use?

2.

What benefits do these techniques bring to the project, the organisation and the construction industry as a whole?

13

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 1 Introduction

3.

Are there any reasons why off-site manufacture may not be adopted, and how can these be overcome?

4.

How does off-site manufacture compare in terms of construction time and cost to traditional building methods?

5.

What improvements could be made to the off-site manufacture procedure to make it more widely recognised and accepted?

6.

In which situations could the larger house builders adopt off-site manufacture to help in meeting housing demand, whilst improving their own efficiency and effectiveness?

7.

How relevant is off-site manufacture in terms of helping to meet current housing demand?

8.

Is off-site manufacture the future of house building?

1.6

Assumptions

Certain assumptions have had to be made in order to undertake the research if the aim is to be proved correct. These are:

1.

That the research can be carried out within the given timeframe.

2.

That the representatives from each organisation will be available to complete the questionnaire and be interviewed within the timeframe of the research period.

3.

That the representatives from each organisation will be willing to divulge potentially sensitive / confidential information on their project, in order to make the research an accurate reflection of off-site manufacture.

14

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 1 Introduction

4.

That the data / information received will be of sufficient quality to formulate suitable conclusions to prove the aim / objectives of the work.

1.7

Outline Methodology

The methodology for the research is shown in the flow chart below:

Conception of idea

Development of idea

Literature Review

Assess questionnaire responses

Conduct questionnaire research

Devise research methodology

Conduct interview research

Assess interview transcripts

Analyse all data and formulate case studies

Conclusions and recommendations

Collate summary of key findings

Conduct benchmarking and KPIs

THE FUTURE IS MODULAR ?

15

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 1 Introduction

1.8

Dissertation Structure

Following this introduction, the dissertation will be split into seven chapters and will be structured as follows.

Chapter 2 Off-site manufacture A History in Construction

The first literature review chapter will summarise the history behind off-site manufacture. It will show how the uptake of the techniques has evolved, from the aftermath of World War II and to the end of the last millennium.

Chapter 3 Off-site manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use

The second literature review chapter will assess current applications of offsite manufacture. It will examine the situation since the turn of this century, and will also explore the implications and applications for future use.

Chapter 4 Successful Projects Using Off-site Manufacture

The final literature review chapter will highlight those organisations that are successfully using the techniques. It will focus on the three organisations under review, namely Urban Splash, Hyde Housing Association and The Peabody Trust.

Chapter 5 Research Design and Methodology

This chapter will outline the methodology for the research. It will refer to the literature in justifying the rationale, as well as detailing the questionnaire format and the principal themes of the interviews.

Chapter 6 Data Analysis and Results Detailed Analysis

This first results chapter will be a detailed analysis of each of the organisations and their projects, and will form the basis of the case study approach.

16

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 1 Introduction

It will follow the format of the questionnaire, while comments and interpretation to some of the responses from the interview will be included where appropriate.

Chapter 7 Data Analysis and Results Benchmarking

The second analysis chapter will be centred on benchmarking and key performance indicators. The results from each organisation will be compared to each other, to the construction industry as a whole and, in particular, to the new build housing sector. Overall construction time and cost relevant to industry standards will also be covered.

Chapter 8 Conclusions and Recommendations

The final chapter will detail a summary of key findings, and draw conclusions by referring back to the objectives to assess what the research has found. It will also highlight recommendations for future application of the techniques, whilst identifying the limitations to the research.

1.9

Chapter Appraisal

This first chapter has laid the foundation for the study by outlining the rationale and stating the aim of the research.

Four key objectives have been identified as critical if the aim is to be proved, while a number of research questions have been posed, which when answered will help to meet these objectives. Certain assumptions have had to be made in order to gain the data and information required and these have also been explained.

Finally, an outline methodology to the research, and a brief summary of each chapter has been detailed. It is now necessary to investigate the existing literature on the topic of off-site manufacture. This will be focus of the next three chapters, commencing with Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction.

17

CHAPTER TWO

OFF SITE MANUFACTURE A HISTORY IN CONSTRUCTION

Modular construction can produce existing, innovative buildings that are cost effective and provide value for money throughout the project lifestyle Alistair Gibb

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

CHAPTER TWO

Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

2.1

Scope of Chapter

The literature review will be split into three chapters. The scope of this first chapter is two-fold. Firstly, to identify what is meant by the various terms concerning off-site manufacture. Secondly, to summarise the history behind off-site manufacture in the United Kingdom construction industry.

It will show how uptake of the techniques has evolved; from the 1800s, through its widespread use following the First and Second World Wars, to the boom periods of the 1950s and 1960s, leading up to the situation at the end of the last millennium. Specific attention will be paid to the large high-rise residential buildings that quickly became a feature of our towns and cities in the 1960s. However, a devastating occurrence with one in particular had long-lasting implications for future take-up.

Finally, the policy agenda will be examined, and reference made to the Latham and Egan Reports. Recommendations in these documents have shaped the applications and processes of off-site manufacture that are commonplace today. As Egan, commented: substantial changes in the culture and structure of UK construction are required to enable the improvements in the project process that will deliver our ambition of a modern construction industry (Egan, 1998). Off-site

manufacture has and will continue to play a vital role in achieving this ambition.

2.2

Definition of the Terms

Off-site manufacture, prefabrication and pre-assembly are part of the spectrum of innovative contemporary techniques available to those seeking greater cost effectiveness in construction (Gibb, 1999). Therefore, a natural starting point is to identify what is meant by the terms off-site manufacture, pre-fabrication and preassembly.

18

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

A number of definitions are available in the literature.

In his 1965 book,

Prefabrication A history of its development in Great Britain, White defined prefabrication as a useful but imprecise word to signify a trend in building technology. He argued that if prefabrication was related to every factory

manufactured product, the term could be stretched so wide as to lose all meaning. Thankfully, in the subsequent 40 years, the word has become commonplace and more precise. For the purposes of this work the following definitions will be used.

Stirling (2003) defines off-site manufacture as any part of the construction process that is carried out in controlled conditions away from the actual site.

The Building Services Research and Information Association (BSRIA) (1998) have proposed definitions for the other terms. They define pre-fabrication as the manufacture of component parts of a building and its services prior to their assembly on-site. The key concept of pre-fabrication is that of adding value to relatively

simple, low-intrinsic-volume materials and sub-components.

BSRIA (1998) goes on to identify pre-assembly as the manufacture and assembly of a complex unit comprising several components prior to the units installation on-site. The key concept here is that of combining several high-intrinsicvalue components into a finished entity, so that upon delivery to site only positioning and connection to relevant supplies / services is necessary before the product is put into use.

Many different terms are used to describe the process of pre-assembly; therefore a number of sub-definitions are also important to note. The following have all been developed by Alistair Gibb (1999 and 2001); a widely recognised authority in the field of research.

Non-volumetric pre-assembly The term non-volumetric is taken to mean those items that do not enclose usable space, and being assembled in a factory prior to being placed in their final position. They may include several sub-assemblies and constitute a significant part of the building or structure. Examples include wall panels, structural sections and pipe work assemblies.

19

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

Volumetric pre-assembly The volumetric category comprises units that enclose usable space, but do not themselves constitute the whole building. These units are also assembled in a factory, and are substantially complete in themselves. This leaves only a small amount of work to be completed on-site, and they are usually installed within an independent structural frame. Examples include toilet pods, plant room units, pre-assembled building services risers and modular lift shafts.

Modular building This category comprises units that form a complete building or part of a building, including the structure. Again, they are substantially complete in themselves, which leaves only a small amount of work to be completed on-site. They also may be clad externally on-site, with cosmetic brickwork as a secondary operation. Examples include out-of-town retail outlets, such as McDonalds Drive-Thru restaurants, office blocks and motels, for example Forte, and, most recently, residential apartments, both by private and social housing developers (this will be discussed in more detail in chapter 3). This type of off-site manufacture will be the main focus of the research.

Figure 1 shows how off-site manufacture can be seen to encompass the other terms, and how the various techniques interact.

20

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

Figure 1 Off-site Manufacture and its related techniques

Off-site Manufacture

Pre-assembly

Pre-fabrication

Non-Volumetric

Volumetric

Modular Building

2.3

Origins of Off-site Manufacture in the United Kingdom

Off-site manufacture is not new to the industry. Gibb (1999) cites examples of timber buildings using off-site manufacture as early as the twelfth century. While a Building Research Establishment (BRE) Report in 2003 highlighted its use in the 1770s with the construction of the first Iron Bridge at Colebrookdale. Other early examples include Londons Crystal Palace, built in 1851 for the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park and then relocated to Sydenham in 1854, as well as the export of houses, churches and hospitals to the colonies during 19th century.

Gibb (1999) feels that industrialised building techniques, however, have not developed steadily and consistently, instead evolving in a sporadic fashion and have even being totally disregarded at times. White (1965) has been more critical. He wrote that the examples of prefabrication before the 19th century were isolated phenomena that had virtually no influence on the later course of building evolution.

Before the First World War, housing standards were extremely poor for much of the UKs population. Therefore, there was a great need to replace the sub-

standard properties as well as to increase the number available for rent (BRE, 2003).

21

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

The impetus for developing mass prefabrication, however, occurred after the Second World War. This was due to the necessity for new housing, following the mass destruction of existing stock that had occurred, and because such numbers could not be produced by traditional methods.

Unfortunately, the ability of what was left of the house building industry to respond to these demands was very limited, as inevitably, there was a shortage of both traditional materials and skilled personnel. These circumstances, therefore,

created the need to reconsider the procurement and construction of buildings to service the demand.

2.4

1914 - 1939

Fortunately, the government recognised the problems of dealing with postwar building at an early stage during the First World War. This led to the formation of the Ministry of Reconstruction in 1917, whose brief was to consider and advise upon the problems which may arise out of the present war and may have to be dealt with on its termination (BRE, 2003). In time, the Ministry was to conclude that it was in the field of steel and concrete housing that prefabrication was most significant.

White (1965), however, summarised that prefabrication in the inter-war period can be dismissed as a brief attempt to introduce alternative buildings methods to the industry, after a lapse of sixty years since the days of the export of cast-iron buildings.

Prefabrication following the First World War had virtually ceased by 1928. This was primarily because it had not managed to consistently compete with traditional building. Its main contribution had been to provide a small additional

number of houses, which would probably not have been built using traditional methods due to material shortages. Essentially, this period had been one that,

although helpful in terms of the number of houses built, remained detached from the approach to building used by the rest of the industry and, therefore, had no long-term impact on construction at the time (BRE, 2003).

22

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

2.5

1939 onwards

Following the destruction caused by the bombings of the Second World War, there was again a shortage of housing stock and a need for the deficit to be reduced quickly. In September 1942 then, an Interdepartmental Committee on House

Construction was appointed. Presided over by Sir George Burt, it became known as the Burt Committee.

Its brief was to consider materials and methods of construction suitable for the building of houses and flats, having regard to efficiency, economy and speed of erection. This included considering the application of prefabrication.

The committees subsequent reports prepared the background for further development of prefabrication, and led to an increase in the number of non-traditional properties being built in the UK. This included timber frame houses, which were imported in significant numbers.

These post-war years were marked by massive government intervention and by the granting of subsidies and, in October 1944, The Housing (Temporary Accommodation) Act was passed. It authorised the government to spend up to

150,000,000 on the provision of temporary housing (BRE, 2003) and between 194548, around 157,000 temporary houses were manufactured, or imported, and erected. However, this was significantly less than the numbers expected, and the gap between expectations and actual provision has contributed to the perception of a poor performance.

Richard Sheppard, in his 1946 book Prefabrication in Building, was an advocate of the techniques. However, instead of questioning its feasibility believing it had been amply demonstrated that efficient buildings could be constructed from mass-produced factory units he summarised achievements in the prefabrication of buildings in England and America.

Sheppard agreed that large measures of prefabrication were required in order to meet both the housing demand and the demand for new schools. However, he

23

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

noted that there was a tendency to assume that prefabrication developed merely to supplement orthodox methods of construction during a period of emergency.

In summary of this period, White (1965) identified that it has been characterised by changes in materials and techniques, which had implications far beyond the field of housing.

A characteristic of the 1950s was the major push to provide increasing numbers of housing units within a very short space of time, while making maximum use of restricted site space. These constraints and cost limits led to the introduction of Large Panel Systems (LPS) Construction, using existing technology first developed in Denmark in 1948 (BRE, 2003).

2.6

Large-panel high-rise residential buildings

In the early 1960s, the first of many tower blocks began to be built in areas of London, such as West Ham an area badly affected by the bombs of the Second World War, and with several approaching slum status. The design chosen for many of these was the Larsen Neilson method: one where pre-cast reinforced blocks are slotted into place on site, then bolted and cemented together. This was seen as a safe and quick way to provide new homes.

In 1965, the London Borough of Newham commissioned nine, twenty-two storey blocks. As the end of the decade approached, many of these tower blocks had been constructed, giving local people a chance to move out of old, usually unfit properties, into smart new homes in the sky. The various social problems created by the tower block lifestyle had not yet come to light and many people were fairly content to move into a new high-rise flat in order to escape damp, dirty and rundown houses.

However, one event had both devastating occurrences and long-lasting implications for the future perception of prefabrication.

24

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

2.6.1

Ronan Point, Newham, East London

Construction of the Ronan Point block started in July 1966, being handed over to the council in March 1968. It was 80ft by 60ft in area and 210ft high, and consisted of 44 two-bedroom flats and 66 one-bedroom flats.

At 5.45am, on 16 May 1968, an explosion occurred in Flat 90, four floors from the top of the building. This momentarily lifted those top floors, while the now

unrestrained flank wall was blown out. When the load from those floors returned, the supporting walls were no longer present to offer any resistance and hence the weight of some of the upper construction descended through a storey height before impacting on the next lower floor of the south-east corner. The modern design of the building had proved to have a major fault, which allowed the domino style collapse of the wall and floor sections.

Only eight flats remained vacant at the time of the explosion and it was fortunate that four of these were situated in the south-east corner which collapsed (BRE, 2003). However, there were still five fatalities (four directly as a result of the explosion and collapse).

The cause was later found to be a build-up of gas from a leaky cooker connection that was ignited by a lady hoping to make an early morning cup of tea, contrary to the initial local rumours that it was caused by an IRA bomb maker gone wrong.

The incident led to a ban on the supply and use of gas in high-rise premises, although this has now been revised, partly due to the difficulties in upgrading and renewing heating methods in the blocks themselves. However, the implications in terms of the publics perception of prefabrication have had long-lasting implications.

2.6.2

Other problems with high-rise LPS systems

Following the collapse of Ronan Point, the then Minister of Housing and Local Government instructed local authorities, in August 1968, to appraise the structural design of the existing and proposed LPS blocks. The BRE noted that this

25

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

programme was intended to reduce the probability of progressive collapse in the event of the loss of load-bearing elements (BRE, 2003). The result was a nationwide programme of assessment and the strengthening of many existing LPS blocks.

However, there have also been other problems with these large-panel highrise buildings. For example, the BRE (2003) has noted that many of the systems have also suffered from water penetration and poor thermal performance. Frequent condensation has also led to concern and dissatisfaction among tenants. However, many of the problems with these systems are a result of poor workmanship rather than design, leading to prefabrication being associated with poor quality buildings. Although the specific problems at Ronan Point were not all related to the form of construction, the publicity has been closely associated with the method of building, which has again contributed to a negative view in some quarters.

Even though the techniques have increased over time, both in terms of scope and number, there has still been prevailing stigma attached to off-site manufacture. Therefore, in order for off-site manufacture to prosper, these problems must be recognised and overcome. This will be discussed in more depth in chapter 3.

However, White (1965) noted that where prefabrication has been successful, there has been a unity of purpose and close collaboration between client, designer, manufacturer and contractor. He felt that many failures since the war can be put down to a lack of effective co-operation and timing whereby the correct solution presented by and to the right people at the right time has often been the basis of the success achieved.

Since those dark times for off-site manufacture, the situation has changed. This has been a result of both advances in innovation and a general improvement in the efficiency of construction firms. As such, the benefits of off-site manufacture are now widely recognised. These have been published by research organisations, such as the Construction Industry Research and Information Association (CIRIA) and the BRE.

The benefits of off-site manufacture are the subject of chapter 3. However, they will be briefly mentioned here. A CIRIA report in 1999, entitled Adding Value to Construction Projects through Standardisation and Pre-assembly, focussed on the

26

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

value to be gained from the application of off-site manufacture. The report concluded that the deliberate and systematic use of pre-assembly, started early in the process, will add value to projects by increasing predictability and efficiency (Gibb, 2001).

2.7

Non-Domestic Applications

Non-domestic applications are generally considered outside the scope of this work. However, it will briefly be touched upon here to ensure the continuity of the historical context, and because the use of prefabrication is well established, while the scope for future application is considerable. This is because the size, shape, form and fabric of non-domestic buildings are more diverse than those found in UK housing (BRE, 2003).

Many commercial clients perceive the construction time of new outlets as a delay in their ability to trade and, as such, apply pressure for faster build times. Fast track construction schemes have been tried for a number of years to reduce time spent developing new outlets, and prefabrication has been identified by many as one of the ways of achieving faster completion. For example, McDonalds Restaurants use prefabrication to build their new outlets, recently setting their record of a completed outlet being built and open for business, in Runcorn, Cheshire, within 13 hours of starting construction on prepared ground (BRE, 2003). They have also built the largest fast-food restaurant in Europe a 2,200m2 unit near Greenwichs Dome in just 15 weeks using modular construction (Robert Gordon University, 2002). These fast, economic developments have considerable commercial implications for the businesses. A range of clients from hotels (such as Travelodge in the form of

prefabricated bathroom pods) to retail outlets are now using some form of prefabricated procurement.

2.8

Policy Agenda

2.8.1

The Latham Report

In 1994, the UKs Joint Review Body published Constructing the Team by Sir Michael Latham. The report, more commonly known as The Latham Report, was jointly commissioned by government and the industry, with the participation of many

27

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

major clients. It was set up to consider procurement, contractual arrangements and the current roles, responsibilities and performance of the participants, including the client (Latham, 1994). The report was produced by a single individual, not a working party or committee, and in the authors own words was a personal report of an independent, but friendly, observer.

In essence, the review attempted to put forward solutions to problems that it had identified were preventing clients from obtaining the high quality projects they required. The report concluded that an enhanced performance could only be

achieved by team work in an atmosphere of fairness to all of the participants a process of finding win-win solutions (Masterman, 2002).

Altogether the Latham Report made thirty recommendations. One specifically important in this context was for a 30% reduction in construction cost. Much of the debate about meeting this target has centred on greater use of industrialised building methods, such as off-site manufacture. Since the publication of the report, Evans (1995) has noted today the pressures on the industry and the capabilities of more flexible manufacturing technology are different from the 1960s. There is a growing sense that now is the time for another push towards economies of scope and towards prefabrication.

The recommendations were initially accepted in principle by all those involved; however, putting them into practice has been slower than envisaged. Furthermore, work on their implementation has been somewhat overtaken by the recommendations of Rethinking Construction.

2.8.2

The Egan Report

The Egan Report Rethinking Construction was published in 1998 by the Construction Task Force. It was commissioned by the Department of the

Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR) as a result of the growing dissatisfaction of both public and private clients with the performance of the industry. The task force was charged with investigating and identifying methods of improving the efficiency of the industry and the quality of its products.

28

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

The report was very critical of the industry for its past poor performance and called for radical change in the way projects were implemented. It concluded that the industry needed to concentrate on becoming more efficient, improving the quality of its output and improving the satisfaction of its clients (Egan, 1998). One of its

recommendations was to move towards sustainable construction, with the emphasis on prefabrication and off-site assembly.

There has been some criticism of the report in certain quarters. This has centred on its provocative and unnecessarily hostile approach and its failure to address the needs of occasional / one-off clients and the implementers of small to medium sized projects that make up a large proportion of the industrys annual workload (Masterman, 2002).

However, the report highlighted how the construction industry should follow the example set by manufacturing as a way of improving effectiveness and efficiency. In particular, the housing sector can be viewed as the frontline for off-site manufacture. The report showed how Housing Associations, such as The Peabody Trust, The Guiness Trust and Southern Housing Group have implemented the lessons learnt from abroad to improve the procurement of low-cost, high-quality adaptable housing. In fact, it went so far as singling out the social housing sector as exemplary, stating: the Task Force believes that the main opportunities for improvements in house building performance exist in the social housing sector. However, we would expect improved practice in social housing to affect activity in the wider housing market (Egan, 1998). Yet, history has proved that the wider housing market and, in particular, the larger speculative house builders are sceptical and slow to copy the success of their not-for-profit counterparts.

The report has also led to a range of initiatives that have had a major impact on the industry, such as the Movement for Innovation (M4I) and the Construction Best Practice Programme. Prefabrication has been identified as a major way forward in delivering these required improvements.

29

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 2 Off-site Manufacture A History in Construction

2.9

Chapter Appraisal

This chapter has set the background for off-site manufacture, prefabrication and pre-assembly in the UK construction industry. It has defined the various terms since an understanding of these is critical to the overall understanding of their application in the industry and has given a brief historical summary, by looking at the origins of off-site manufacture, from sporadic beginnings pre-19th century to more widespread adoption following the two World Wars. This was in an attempt to deal with the chronic shortage of housing stock that resulted from the devastating bombings. It showed how the techniques supplemented the more traditional

methods, rather than providing the answer to all the industrys problems.

From there, it has been shown how government intervention in the 1940s and uptake of methods increased in the 1950s and 1960s. However, a notable

occurrence the Ronan Point block collapse has resulted in the techniques suffering from a poor perception among the wider population.

Finally, recent government-sponsored policy agenda has been investigated. This has taken the form of the Latham and Egan Reports reports that were intended to change the way the construction industry operates by encouraging firms to become more like the manufacturing industry through greater adoption of increasingly industrialised building techniques.

It is now necessary to assess whether the recommendations made by Sir Michael and Sir John have had an effect on the uptake of off-site manufacture in the industry. This will be the focus of chapter 3, along with an evaluation of the benefits and potential barriers to adoption. Finally, it will summarise the applications of offsite manufacture since the turn of the new century up to the present day.

30

CHAPTER THREE

OFF-SITE MANUFACTURE CURRENT APPLICATIONS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE USE

Prefabrication is much more than a trendy concept, it offers the possibility of remoulding construction as a manufacturing industry. It represents one of the positive ways forward for underpinning the major changes that have been identified as necessary for improving construction Building Research Establishment

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 3 Off-site Manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use

CHAPTER THREE

Off-site Manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use

3.1

Scope of Chapter

This chapter will assess whether the recommendations made in the Latham and Egan Reports have had an affect on the industry by detailing the current applications of off-site manufacture, from the start of the millennium up to the present day. It will show how the industry is now applying the techniques in various forms.

The benefits of off-site manufacture are both widely recognised and publicised, and will be discussed to improve the overall understanding of the current situation. Some of these benefits will impact directly on project performance and cost, while others have more indirect advantages to both the client and project team.

However, there are still various barriers to adoption. A number of these have resulted from the perceived poor performance of the techniques during difficult periods in the 1960s. These will be detailed, and it will be shown how they can be overcome, and how successful projects using off-site manufacture can be developed as a result.

Finally, the chapter will explore the applications and implications for future use, as off-site manufacture is much more than a trendy concept. Instead, it could offer the possibility of remoulding construction as a manufacturing industry. These methods are being used in an attempt to meet the housing targets set by the Deputy Prime Minister.

3.2

The Current Situation

The UK construction industry is currently using prefabrication in a wide variety of forms and applications. This ranges from the simple prefabricated site hut, to volumetric units that can be delivered to site and integrated into the structure of a building.

31

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 3 Off-site Manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use

The BRE (2003) has identified modularisation or modular design as key to prefabrication. Modular design refers to construction using standardised units or

standardised dimensions. Modular buildings do not have to be built by prefabricated techniques, however they are usually involved. A variety of successful modular

developments have recently been procured in the UK and these will be described in chapter four.

Off-site manufacture is not just limited to the building fabric, but can also be applied to the plant and services within a development. BSRIA recently completed a DETR study into the application of prefabrication of services (Wilson, Smith and Deal, 1998). This included a comparison with the traditional approaches and

identification of some of the issues that determine whether the approach is successful. The prefabrication of building services is generally considered outside the scope of this work. context of current uses. However, it is mentioned here to provide an up-to-date

An important point to note is that the implementation of off-site manufacture in the UK has been sporadic. It is often dominated by the larger construction

companies, which have shown most interest in using prefabrication techniques to improve productivity and move towards leaner construction (BRE, 2003). The

concept of lean construction was one of the main recommendations by Sir John Egan. However, uptake of off-site manufacture by the house building industry, and in particular the larger developers, has been much slower. Instead, it has been the smaller developers, and notably the Housing Associations, who have used the techniques to great effect. Perhaps an explanation for this is because they are more concerned with client satisfaction and quality of product than profit margins and share prices. In reality, the larger speculative house builders need more convincing of the benefits, as they have more to lose if things go wrong, in respect of the relationship that they have with their shareholders.

In April 2000, the DETR produced a Housing Green Paper entitled Quality and Choice: A Decent Home for All. This identified prefabrication as a means of providing affordable housing, and considered the ways in which more resources could be used. Specifically, the paper stated: we expect to see progressive take-up

32

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 3 Off-site Manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use

of the technique over the next few years, for both social and private house building, as the benefits are more clearly demonstrated (DETR, 2001a).

3.3

Benefits of Off-site Manufacture

Off-site manufacture has many benefits to the industry as a whole, as well as at project level. Much of this benefit and added value is indirect. Davis Langdon (2004) note that, while the cost issue remains unresolved, the supporters of off-site manufacture argue a broader case based on social and environmental issues.

For example, using prefabrication allows the time spent working on site to be reduced. This means that the impact of the site on the local environment is for a shorter period of time. Furthermore, site work is traditionally vulnerable to disruptions from extremes of weather. By using prefabrication, the site will be vulnerable for a shorter time, and hence, the risk of delay and the requirements for protection will be reduced. Fast track construction systems often use prefabricated components to rapidly erect a weather tight shell for the building. This enables the internal fit-out to be moved forward in the process and continue despite the external weather conditions.

Many of the benefits of prefabrication will be gained when it is considered early in the design process, and ideally at the concept design stage (Reid, 1999). Alternatively, problems of a lack of compatibility, and a resulting increased cost, can occur where the techniques are not considered until later in the process. In fact, prefabrication requires all involved in the process to go through a learning curve to optimise the benefits of using the system.

All these factors have benefits to the programme. As Davis Langdon (2004) point out, there are opportunities to compress project durations and reduce risk by transferring work off site and by simplifying site operations and on-site snagging. However, the downside of this programme compression is that more work needs to be completed pre-contract, and hence earlier design freeze dates are required.

33

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 3 Off-site Manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use

Prefabrication can also offer opportunities for dealing with the problems of the declining workmanship standards and skilled labour shortages on site. This was something that was highlighted as a way of meeting Egans targets. In a factory environment, the quality of the finished product is much easier to assure than on site. All that remains is to ensure that the on-site assembly meets the required standards to allow the design to perform to its requirements. However, the BRE note that careful attention is needed with this, as it has been a stumbling block in the past application of prefabricated systems (BRE, 2003). In fact, concern has been voiced that the very move to prefabrication will further reduce the skills base in the industry. In 2001, Ian Davis, the Director General of the Federation of Master Builders said: increased prefabrication is seen as one answer to problems that beset the industry, including the skills shortage, inconsistent quality and low margins. Whilst

prefabrication has a role in improving the industry it must not be pursued at the expense of the skills shortage training needed for traditional forms of construction.

Careful quality control of manufacturing processes enables waste to be controlled and minimised through appropriate design and recycling opportunities. In addition, the use of prefabricated components should cut the volume of site spoilage associated with current practices of over-ordering and poor site handling for the equivalent traditional processes.

Benefits of quality are derived from standardised processes under factory conditions. Davis Langdon (2004) point out that one of the benefits of the factory process is that improvements developed on one project can progressively improve the basic product. This has further benefits in respect of safety and working

conditions, in that safety improves by transferring work into a controlled environment.

Davis Langdon (2004) identify another benefit in the whole life costing. Enhanced specification standards and build quality can also reduce occupancy costs related to energy use, defects and repairs. However, these benefits of good whole life performance can be offset by high costs of adaptation. On large projects, economies of scale can be achieved through off-site manufacture with orders of 500 units attracting a discount of 5 10% (Davis Langdon & Everest, 2002). These savings will be partially offset by transport costs

34

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 3 Off-site Manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use

and on smaller projects additional design and set-up costs. However, there are also further indirect savings through reduced site supervision, simplified inspections, fewer variations and less re-working.

3.4

Barriers to Application

Robert Gordon University conducted a government sponsored research report in 2002 entitled Overcoming Client and Market Resistance to Prefabrication and Standardisation in Housing. It examined potential barriers to the use of

prefabrication and the ways in which these may be overcome. Six key areas were highlighted.

3.4.1

General Image

The image of prefabrication has been clouded by the experience of past applications and, in particular, the 1960s high rise housing schemes. However,

many of these problems have resulted from poor workmanship rather than design deficiencies (Robert Gordon University, 2002). The effect has been that these

experiences present a barrier to some parts of the industry accepting prefabrication as a viable method of building procurement.

This is now being countered through one-off demonstration systems, where close supervision of site activity ensures that the end result is a product with workmanship quality equivalent to that of traditional systems (BRE, 2003). Thus, the quality of assembly is important in ensuring the long-term success of prefabricated systems. An indication of fitness for purpose for the Murray Grove development is the fact that no alterations to the form or fabric of the building has been carried out in the six years since completion (Spring, 2006).

3.4.2

Perceived Performance

Many of the prefabricated buildings that were constructed between 1946 and the mid-1970s have been viewed as having a shorter lifespan than that of equivalent traditional buildings. The Robert Gordon University (2002) study noted that the

35

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 3 Off-site Manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use

perception that prefabrication offers a non-permanent solution is one of the potential barriers that exist for its wider acceptance as a mainstream procurement option.

Building Magazine recently instigated a return visit to the modular Murray Grove development in North London seven years after its construction to assess whether the reality has lived up to expectations. The result was positive, with good performance being achieved in the critical areas of functionality and build quality, and moreover, the building has low maintenance costs. Although not without its teething problems, such as noise penetration, Murray Grove has shown that barriers such as the perceived performance can be overcome.

3.4.3

Customer Expectation

One barrier to adoption in housing, in particular, is the perception that the public want a traditional brick finished house. However, the masonry industry is developing new factory prefabricated systems that can be delivered to site, and which maintain the traditional masonry appearance (Robert Gordon University, 2002).

Positive feedback has again been received from the Murray Grove site. It indicated that tenants are attracted by the modern external appearance of the building, which suggests a possible move away from traditionally finished houses in some quarters of the housing industry.

3.4.4

Perceived Value

It has suggested by Craig, Laing and Edge (2000) that resistance to off-site manufacture, particularly in the housing sector, is partly caused by the perception that property is an investment. As such, off-site manufacture is not necessarily seen to be a good investment, based on historical experience.

Evidence from Murray Grove has suggested that the build cost was 5% more than traditional construction costs, according to the BRE. The construction cost was 1,015/m2, with the average cost per flat of 77,800 (Spring, 2006). However,

36

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 3 Off-site Manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use

maintenance costs at Murray Grove are also considerably lower than the Building Cost Information Service comparison - 7,000 per annum for external and internal maintenance compared to 34,400 (Spring, 2006).

3.4.5

Industry Culture

One factor the Robert Gordon University (2002) report found that is restraining the use of some prefabrication in housing is the availability of plant for handling the larger systems on site. They found that a change in site culture, and industry use of plant, would encourage the use of panel prefabrication systems.

Furthermore, the attitude of the construction industry has suggested that it is reluctant to try new methods and believes that off-site manufacture will cost more than traditional methods of construction. Despite evidence to the contrary, this

attitude, still found in some parts of the industry, is difficult to counter.

3.4.6

Product Awareness

The procurement of prefabricated components for a project is often a matter of designers being aware of the availability of a given system. The BRE (2003) note that designers are unlikely to use a system for which they do not appreciate the benefits for the construction, or for which they do not understand how the system impacts on the design process. Manufacturers are producing innovative

prefabricated products; however they consider that it is the designers that are conservative and reluctant to try out new systems (Reid, 1999).

Davis Langdon (2004) highlight two further potential barriers to adoption as being the need for project specific research and issues with planning. There are more than 40 different suppliers of panellised and volumetric systems in the UK, with no standard means of comparison or historic cost data (Davis Langdon, 2004). Greater availability of information concerning the competitive position of alternative technologies would enable clients to proceed without having to undertake their own comparative studies. Furthermore, decisions by planners can act as a constraint by

37

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 3 Off-site Manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use

influencing the layout and appearance of buildings, or by extending the preconstruction period.

The barriers mentioned above are often based on a perception of difficulties that have arisen from past experience, rather than from actual technical constraints. However, none of these barriers should exist if the industry is educated of the merits of using prefabrication (BRE, 2003). Furthermore, it is important to note that some aspects of prefabrication used in construction have managed to avoid many of these problems and are now well established systems.

The real test for prefabrication is to move from the successful one-off demonstration projects to mainstream developments. Both private and social

housing markets will provide the keys for this success. A number of successful projects that have used off-site manufacture are examined in chapter four.

3.5

Applications for Future Use

Off-site manufacture is currently used to some degree in all aspects of construction. However, the extent of this future application can be affected by the barriers previously mentioned. In fact, the most important challenge for the future of off-site manufacture is to overcome these barriers and, in particular, to ensure that the mistakes of the past are not repeated (BRE, 2003). Failure to do this will result in off-site manufacture not meeting its massive future potential.

Off-site manufacture is much more than a trendy concept, it offers the possibility of remoulding construction as a manufacturing industry. It represents one of the positive ways forward for underpinning the major changes that have been identified as necessary for improving construction (BRE, 2003).

Off-site manufacture has the capacity to drive down costs and improve productivity. However, claims for the level of improvement that could be achieved need to be scrutinised and evidence is required to support them. With regard to the other benefits, all the issues need to be understood and properly demonstrated

38

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 3 Off-site Manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use

before the more conservative parts of the industry respond. This, in turn, should lead to a greater uptake of the systems.

The potential environmental benefits of off-site manufacture are numerous. However, real assessments are required of the different applications to show whether these benefits are marginal, or more significant, when compared to traditional methods. Furthermore, environmental legislative pressures on construction activity are likely to continue to grow in the future. If the environmental benefits can be demonstrated for some of the techniques, then they should flourish in the future.

A BRE report in 2003 noted that off-site manufacture could allow greater client choice and involvement, particularly in housing, where a variety of different systems can be realised from manufacturers. However, Alistair Gibb has noted their application and drivers, pragmatism and perception need to be considered in the light of current technology and management practice (Gibb, 2001).

The future application of off-site manufacture in the UK will be determined by the economic and environmental benefits for the particular applications. In order to ensure that these are successful, the performance of the systems needs to be established over the whole life of the structure. Furthermore, without market

acceptance of the end product, off-site manufacture will not flourish. Therefore, it is important to ensure that the aesthetics of the system meet market demand. This is a design, rather than technological, challenge.

3.6

Chapter Appraisal

This chapter has assessed whether the recommendations made by Sir Michael Latham and Sir John Egan have had the desired effect on the industry. It has detailed the current applications of off-site manufacture, from the turn of this century to the present day. Consequently, the industry is now applying the

techniques in a variety of forms and applications.

The benefits of off-site manufacture are widely recognised, and these have been highlighted as a way of improving the overall understanding of the current

39

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 3 Off-site Manufacture Current Applications and Implications for Future Use

situation. These beneficial effects have been described in terms of factors such as performance and cost, while more indirect advantages to all parties that advocate the techniques have also been mentioned.

However, there are still various barriers to adoption. In a number of cases, these have resulted from the perceived poor performance of the techniques during past decades. Although, it has been shown how these difficulties can be overcome.

The chapter has also explored the applications and implications for future use in delivering quality housing in an attempt to meet the governments targets. Off-site manufacture offers the possibility of remoulding construction as a manufacturing industry this was one of the issues that laid the foundation of the Egan Report.

It is now necessary to examine those organisations that are successfully using the techniques. Examples will be drawn from both the private and social

housing sectors. Through detailed examination, it will be shown where the benefits lie and where the larger house builders should take heed.

40

CHAPTER FOUR

SUCCESSFUL PROJECTS USING OFF-SITE MANUFACTURE

Murray Grove has been hailed by the Government and others as a breakthrough for innovative housebuilding. We hope it will prove a catalyst for innovation in the industry as a whole Dickon Robinson, Director of Development, Peabody Trust

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 4 Successful Projects Using Off-site Manufacture

CHAPTER FOUR

Successful Projects Using Off-site Manufacture

4.1

Scope of Chapter This chapter will examine those organisations that are successfully using off-

site manufacture. Reference will be made to Urban Splashs Moho development in Manchester; Hyde Housing Associations Barling Court and Corbet House sites in London; and Murray Grove and Barons Place, developments by The Peabody Trust, also in London, which all deploy off-site manufacture to great effect. They have featured heavily in trade magazines, the national press and an architectural exhibition, as pioneering developments in the pursuit of greater use of modern methods of construction. design and construction. They have won numerous awards for their innovative

Through detailed examination of such successful projects, it will be shown where the benefits lie to the industry, and where the larger house builders can learn from their smaller counterparts.

4.2

Successful Projects using Off-site Manufacture

Following the Egan Report, developers such as Urban Splash and Housing Associations such as Hyde and The Peabody Trust have implemented off-site manufacture to great effect. These volumetric and modular developments, for both the private and key-worker sectors, have recently received much recognition and credit in sources such as Building.

Each of these successful developments will now be examined in more detail to improve the understanding of the benefits to the house building industry as a whole.

41

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 4 Successful Projects Using Off-site Manufacture

4.2.1

Moho Urban Splash

Moho is a pioneering development of 102 flats in Manchester by developers Urban Splash and architects ShedKM. Arguably, it has made prefabricated housing fashionable.

Figure 4.1 Urban Splashs Moho Development

(Source: courtesy of Urban Splash)

The seven storey development of fully furnished units is the UKs first privatesector multi-storey housing development to be based on prefabricated volumetric units. While other house builders were hesitating with off-site manufacture, Urban Splash went the whole hog. This was as a result of a greater demand for smaller, compact units to suit young graduates or key workers and to do so within a tight timeframe, to a high quality and without defects (Spring, 2005).

What makes Moho unique is that the modules are realigned end-to-end to give maximum window space, and it is the first scheme with each flat contained within a single module. However, as Spring (2005) points out, there is no

claustrophobic feeling. In fact, he notes there is a liberating sense of space and daylight, with the living room looking onto a communal courtyard through floor-to-

42

London South Bank University Dept. of Property, Surveying and Construction MSc Dissertation

William Clayton (No. 2402164) Chapter 4 Successful Projects Using Off-site Manufacture

ceiling glazing.

The flats also benefit from clip-on balconies, which shade the

windows from the high summer sunshine. With an internal area of just 38m2 the flats are small. However, innovative thinking by ShedKM, using principles derived from yacht design, ensures that all available space is used efficiently. For example, storage areas are hidden behind sliding doors in odd corners off the bedroom. Even the furniture is yacht-inspired and has been supplied by furniture shop Mooch.

The flats are arranged in three seven storey wings, around a central courtyard serving as a communal garden for residents, and doubling-up as the roof of a car parking podium one floor above street level. The ground floor on all sides is

occupied by shops and cafs that open onto the pavement.

Unlike other schemes, there has been no attempt to disguise Mohos modular construction, with its faades being made up of rectilinear grids of panels, which the architects call a modular Cubist look (Spring, 2005).

Overall, Moho should be popular with young people setting up home. The starting price of 131,000 might prove to be a sticking point, however, being a little above the starter homes average; although, as Spring (2005) notes, that seems a small price to pay for contemporary, urban chic, and modular housing has at last found a place within the aspirational world of young urban professionals.