Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

4/30/13 Concert Program

Загружено:

allenwyuАвторское право

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

4/30/13 Concert Program

Загружено:

allenwyuАвторское право:

BRA HMS, Johannes (1833 1897)

Variationen ber ein Thema von Jos. Haydn fr zwei Pianoforte, op. 56b (Variations on a Theme by Haydn for two pianos) Thema (Chorale St. Antoni) Andante con moto Vivace Con moto Andante Poco presto Vivace Grazioso Poco presto Finale

Sarah Liu, piano Allen Wong Yu, piano SCHU MANN, Robert (1810 1856) Fantasiestcke, op. 12 Des Abends Aufschwung Warum? Grillen In der Nacht Fabel Traumes Wirren Ende vom Lied

Allen Wong Yu, piano CHOPIN, Frdric (1810 1849) Scherzo No. 2 in B-flat Minor, op. 31 Nocturne in D-flat Major, op. 27, no. 2 Sarah Liu, piano DVOR K, Antonn (1841 1905) Slovansk tance (Slavonic Dances) for four hands, op. 46, B. 78 No. 1 in C major (Furiant) No. 6 in D major (Sousedsk) No. 8 in G minor (Furiant) Allen Wong Yu, piano Sarah Liu, piano

Variations on a Theme by Joseph Haydn

Johannes Brahms

In the summer of 1873, Brahms went on vacation in southern Germany, renting rooms in an inn called the Water Lily and playing a derelict piano owned by the inn. He appeared to have immensely enjoyed himself, writing that the view was more beautiful the other day than we could imagine The lake was almost black, splendidly green on the shore, but usually the lake is blue, a more beautiful, deeper blue than the sky. And besides there was the chain of snowcapped mountains you never get tired of looking at it. It was likely a welcome relief for Brahms, who had recently been involved in disagreements with two of his closest friends, the violinist Joseph Joachim, with whom he collaborated frequently, and Clara Wieck Schumann, the wife of his mentor, Robert Schumann. The retreat from the problems of his everyday life allowed Brahms an immensely productive summer. Brahms had not written a theme-and-variation work in ten years, but he decided to finally return to that musical genre, using a theme attributed to Franz Joseph Haydn called Chorale St. Antoni (Chorale of Saint Anthony), which had been discovered by Brahms friend and Haydns biographer, C. F. Pohl. The work consists of the theme, eight variations, and a finale, which itself is a collection of the theme in various iterations. When writing variations, composers in the nineteenth century considered several factors. First, the variations could not move to distant keys, but could only be either in the tonic key of the theme, which here is B-flat major, or its minor mode, B-flat minor. Additionally, one must conserve some aspect of the theme throughout the variations. This posed a challenge because composers often present musical interest, drama, and tension through modulations to different keys and the incorporation of new thematic material. Yet, in this work, the theme-and-variation form constrained Brahms to one key and one essential theme and structure. To overcome these challenges, Brahms used several approaches. First, the theme itself is memorable and structurally interesting. It contains two melodies, the first in two five-bar phrases, and the second in two four-bar phrases. The somewhat off-balance, uneven structure of the theme thus gave Brahms room with which to experiment in the following variations. Furthermore, the later variations draw on material from the earlier ones, so that

motivic material from one variation will be heard in the next, giving the work a sense of development. The theme never really returns in its original form until the finale. However, when it returns, it has undergone its own transformation. That transformation, according to conductor Leon Botstein, is like a phoenix emerging out of its own ashes, but with a difference: the charming little theme from the opening has vanished and though almost exactly the same, it now carries with it a sense of triumph and grandeur.

Fantasiestcke, op. 12

Robert Schumann

In 1828, Robert Schumann arrived in Leipzig to attend university as a law student, yet he found his calling not in academia but in improvising at the piano. With the reluctant blessing of his parents, Schumann began taking lessons with Friedrich Wieck. It was not long before Schumann had fallen in love with Clara, Wiecks prodigiously talented daughter. Wieck strongly opposed a match between Schumann and Clara, however, and forced the young couple (who had been secretly engaged) to separate for four years until they were finally married in 1840. It was in 1837, during the time of their estrangement, that he wrote the set of eight pieces of the Fantasiestcke, op. 12. During this time, Friedrich Wieck had instructed her daughter to return all of Schumanns letters, and he prevented any meeting between the two. Despaired in his courting of his beloved Clara, Schumann turned to drinking and attempted to find interest in other women. In August of 1837, he wrote to the attractive, eighteen-year-old, Yorkshireborn pianist Robena Laidlaw, the period of your stay [in Leipzig] will always remain a really beautiful memory for me, and you will find the truth of what I write all the more clearly in eight Fantasy Pieces. Originally published in two volumes, Schumann dedicated the Fantasiestcke to Laidlaw, with whom he had grown quite close. In many of his critical writings, Schumann wrote with the pseudonyms Eusebius and Florestan, which represented the active and passive aspects of his dual personality. It is clear that Schumann composed these eight pieces with both Eusebius and Florestan in mind, with Eusebius playing the contemplative dreamer and Florestan the flamboyant and passionate lover.

In Des Abends (At Evening), Schumann presents a gentle and peaceful evening scene, a fitting introduction to the dreamer Eusebius. In the early morning, Aufsc hwung (Soaring) introduces Florestan indulging in his desires, where the main themes powerful, unstable dotted rhythm is answered by a more lyrical, vocal line. In Warum? (Why?), Schumann returns to Eusebius, possibly questioning the excesses of Florestan in the previous piece. It is contemplative, with a syncopated rhythm and inconclusive cadences. Schumann ends the first volume with the capricious Grillen (Whims), which represents Florestan in a strange yet whimsical dance in triple meter. In der Nacht (In the Night), which opens the second volume, is really the centerpiece of the cycle. Not only is this the longest of the eight pieces, but its ABA scheme is complicated by a long transitional section and a return to A that is substantially recomposed. This is the first time where both Eusebius and Florestan truly interact, with the dichotomy of passion and serenity. After Schumann composed this piece, he likened it to the touching story of Hero and Leander. Fabel (Fable), like In der Nacht, contrasts the tranquil Eusebius to the anxious Florestan and varies in mood as the narrative unfolds. The rhythmically intense and rapid Traumes Wirren (Troubled Dreams) explores Schumanns struggle between his two characters and his own dreams and passions. Finally, Schumann ends this volume with Ende vom Lied (End of the Song). The instruction Mit gutem Humor does not mean to play in a humorous manner, but to evoke the idea of changing moods. Although the piece was dedicated to Laidlaw, Schumann made reference to it in a letter to Clara years after its completion: toward the end, my sorrow over you returned, and so it sounds like a combination of wedding bells and death knells. The piece begins with full chords, but ends with a solemn, slow, and quiet coda, reminiscent of bells tolling deep into the night.

Scherzo No. 2

Frdric Chopin

By 1836, Chopin had moved from his Polish homeland of Warsaw and established himself in Paris, befriending people such as Robert & Clara Schumann, Franz Liszt, and Felix Mendelssohn. He had already written his monumental Ballade No. 1 and Concerto No. 1, but one of the most important, life-changing events in his life has yet to come. On 24 October 1836, Chopin was invited to perform at a reception at the Htel de France given by Franz Liszt and his mistress, the Countess Marie dAgoult. One of the guests in attendance was the infamous Parisian writer Aurore Dudevant, better known by her pseudonym, George Sand. Despite their relative fame, the two had never met and Sand had never heard Chopin perform. The pair parted with differing impressions of one another. Chopin reportedly remarked, What a repulsive woman Sand is! But is she really a woman? I am inclined to doubt it. On the other hand, Sand wrote that there was something so noble, so indefinably aristocratic [about Chopin]. Yet, only weeks after they had met, Chopins views of Sand had already rapidly changed. He wrote in his diary, I now have seen her three times. She looked deeply into my eyes while I played My heart was captured! ...Aurora, what a charming name! The same year ended with the promising beginning of what would become a ten-year relationship, the most important one in Chopins life, and it was at this time that he began work on the Scherzo No. 2. The Scherzo opens with an ominous and mysterious pair of triplets that quickly explode in a burst of sound. However, the music moves quickly into an immensely varied landscape of sound, through emotions and melodies of all kinds, ranging from a graceful waltz-like section to a muted chorale. Robert Schumann is said to have compared the work to a Byronic poem, so overflowing with tenderness, boldness, love and contempt. Though despite the myriad directions in which the work moves, the fateful, ghostly triplets always return, maintaining the force that drives the work to its energetic and dramatic end.

Nocturne in D-flat Major, Op. 27, No. 2

Frdric Chopin

Although the Irish composer John Field was the originator of the nocturne as a character piece for the piano, it was Frdric Chopin who became a key proponent of this musical genre and whom today one associates most with nocturnes. These works typically feature a lush, singing melody over an arpeggiated, sonorous accompaniment. The two nocturnes in this opus were composed in 1836 and published in 1837. In 1836, Chopin traveled to Leipzig to visit Felix Mendelssohn, as well as to meet Robert Schumann and his fiance, Clara Wieck. During his visit, Mendelssohn and Chopin spent an entire day playing music for each other, and one of the pieces that Chopin performed for Mendelssohn was his new Nocturne in D-flat Major. Mendelssohn enjoyed the work so much that he decided to memorize it immediately. The nocturne essentially consists of two strophes, or musical stanzas, and each is repeated in increasingly complex variations and with progressively elaborate ornamentation, finally culminating in a highly decorative, filigreed fioritura line, or a flowery line found in many nineteenth-century operatic arias. The elegant and extremely romantic melody is always played by the right hand, with the left hand only playing a quiet, supporting, arpeggiated line. While Chopin wrote twenty-one nocturnes for the piano, the Chopin scholar Frederick Niecks wrote of this particular nocturne that, nothing can equal the finish and delicacy of execution, the flow of gentle feeling lightly rippled by melancholy, and spreading out here and there in smooth expansiveness.

Slavonic Dances

Antonn Dvork

A self-confessed simple Czech musician of humble origins, Antonn Dvork owed much of his early successes to Johannes Brahms. In a letter to his Berlin publisher Fritz Simrock in 1877, Brahms wrote, I have been receiving a lot of pleasure for several years from the work of Anton Dvork of Prague. He is certainly a very talented fellow. Brahms convinced Simrock to publish Dvorks Moravian Duets in 1878, and its immense success led to Simrocks subsequent commission that same year for Dvork to compose a set of dance pieces similar to the popular Hungarian Dances of Brahms, but in the Czech spirit. Originally written for a piano duet and later orchestrated by the composer himself, Dvork completed the first book of the Slavonic Dances in less than three months. Unlike Brahms Hungarian Dances, which were mostly variations and arrangements of existing Hungarian melodies, Dvorks pieces were entirely original, composed in the dance styles of Czech, Polish, Ukrainian, Serbian, and other Slavonic regions. The Slavonic Dances begin with No. 1 (C Major) in the fiery and jubilant style of a furiant dance, with the typical alternation between 3/2 and 3/4 time. No. 6 (D Major) is a charming sousedsk waltz with a beautiful and lyrical melody. The first book ends with No. 8 (G minor), which is another furiant dance even more exciting than the first. On the centenary of Dvorks birth in 1941, while Prague was under the occupation of the Third Reich, the legendary conductor Vclav Talich of the Czech Philharmonic said this about the Slavonic Dances: The dances transformed into a symboldemonstrating how our people sing and how they weep, how they rejoice and how to contemplate, how they suffer and how they have faith. No, Dvork has not given us Slavonic dances, rather the Czech people through his medium have sung out the rhythm of their lives.

~ Allen Yu & Sarah Liu

Brunswick, Maine April 2013

BOWDOIN CHORUS & MOZART MENTORS ORCHESTRA

Thursday & Friday, May 2 & 3 at 7:30pm Studzinski Recital Hall Bowdoin Chorus and Mozart Mentors Orchestra, conducted by Anthony Antolini, will present the world premiere performance of Delmar Dustin Smalls As It Began to Dawn an oratorio about the awe and mystery of the morning of the Resurrection and Jesus subsequent appearances to his disciples.

BOWDOIN CHAMBER CHOIR

Saturday & Sunday, May 4 & 5 at 3:00pm Bowdoin Chapel Robert K. Greenlee will lead the Chamber Choir in a program of American music, including the premiere of a work by Elliott Schwartz.

PIANO STUDENTS OF GEORGE LOPEZ

Sunday, May 5 at 7:30pm Studzinski Recital Hall

RACHEL LOPKIN 13, flute & Friends

Friday, May 10 at 7:30pm Studzinski Recital Hall

KATARINA HOLMGREN 13, voice

Saturday, May 11 at 4:00pm Studzinski Recital Hall

Pianist Allen Wong Yu, 20, is an acclaimed performer, recognized for his mature musicianship, elegant tone, and charismatic stage presence. Allen has appeared as a soloist in major venues in Albany, Schenectady, Rochester, Oneonta, Ithaca, Binghamton, Saratoga, Springfield, Portland, and Brunswick. During his time abroad in Italy, he also presented solo recitals in Milan and Ferrara. Highlights from his past seasons include the Schumann Carnaval, Mendelssohns Fantasies or Caprices, and Mussorgskys Pictures at an Exhibition, as well as the Schumann and Dvork Piano Quintets. In February 2012, Allen appeared on National Public Radios From the Top for the second time; his first appearance on NPR was in 2008 when he performed as a Jack Kent Cooke Young Artist. Born in California and a native of Beijing, Allen began studying piano at the age of six and won his first major competition at ten. He delivered his solo debut at age twelve and his critically acclaimed orchestral debut a year later. A junior at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine, he is currently pursuing his studies in political science and piano performance. At Bowdoin, he serves as Vice President of the student body on Bowdoin Student Government. He is also a Past Distinguished Governor of New York for Key Club International, a service leadership program of Kiwanis International. Allen studies with pianist George Lopez, Bowdoins Artist-in-Residence. Pianist Sarah Liu, from Albquerque, New Mexico, began playing the piano at age six. Studying under the acclaimed New Mexican teacher and pianist Lawrence Blind, Sarah has received numerous awards and honors, including prizes in the New Mexico Symphony Orchestras Young Artists Concerto Competition for Piano and Strings, as well as in the Honors Auditions held by the Professional Music Teachers of New Mexico. Composer and pianist Dennis Alexander has described her performance as elegant and thoughtful, with lyrical playing [which] really drew the audience in and commanded them to listen. Sarah is currently a senior at Bowdoin College, where she studies biology as well as piano performance with George Lopez, Bowdoins Artist-in-Residence. At Bowdoin, she has participated in numerous chamber music groups in addition to her solo performances. She also serves as co-president of the Bowdoin Outing Club, and enjoys whitewater kayaking and backpacking.

We would like to thank the faculty and staff of the Bowdoin College Department of Music for making tonights recital possible. We are especially grateful to our teacher, George Lopez, whose enthusiasm, passion, and love for music never fail to inspire us. A special thanks to our advisors, Professor Robert Greenlee and Professor Mary Hunter, for continuing to support us to grow as scholars and musicians. We hope youve enjoyed this performance. Please visit www.bowdoin.edu/music for a listing of upcoming events.

In consideration of the performers and those around you, please kindly switch off your cellular phones, pagers, and watch alarms during the recital. Please do not take pictures during the performance. Flashes, in particular, are distracting to the performers and other audience members. Thank you.

Вам также может понравиться

- Allen at Home - Recital Program (8/28/2020)Документ2 страницыAllen at Home - Recital Program (8/28/2020)allenwyuОценок пока нет

- 4/19/12 Solo RecitalДокумент12 страниц4/19/12 Solo RecitalallenwyuОценок пока нет

- 12.06.13 Solo RecitalДокумент12 страниц12.06.13 Solo RecitalallenwyuОценок пока нет

- 4/15/14 Recital ProgramДокумент16 страниц4/15/14 Recital ProgramallenwyuОценок пока нет

- 4/30/13 Recital Poster 1Документ1 страница4/30/13 Recital Poster 1allenwyuОценок пока нет

- 12/06/13 Recital Poster 1Документ1 страница12/06/13 Recital Poster 1allenwyuОценок пока нет

- 4/30/13 Recital Poster 2Документ1 страница4/30/13 Recital Poster 2allenwyuОценок пока нет

- 4/15/14 Recital PosterДокумент1 страница4/15/14 Recital PosterallenwyuОценок пока нет

- 12/06/13 Recital Poster 2Документ1 страница12/06/13 Recital Poster 2allenwyuОценок пока нет

- 4/19/12 Recital Poster 2Документ1 страница4/19/12 Recital Poster 2allenwyuОценок пока нет

- 12.3.15 Bowdoin - Edu HomepageДокумент1 страница12.3.15 Bowdoin - Edu HomepageallenwyuОценок пока нет

- 12.3.19 From The Top Green Room - 247 Listening GuideДокумент5 страниц12.3.19 From The Top Green Room - 247 Listening GuideallenwyuОценок пока нет

- 4/19/12 Recital Poster 1Документ1 страница4/19/12 Recital Poster 1allenwyuОценок пока нет

- 11.11.18 BDS Renowned Recitalist Christopher O'Riley Master Class To Include Pianist Allen Wong Yu '14Документ1 страница11.11.18 BDS Renowned Recitalist Christopher O'Riley Master Class To Include Pianist Allen Wong Yu '14allenwyuОценок пока нет

- 12.2.1 Bowdoin - Edu - NPR Show 'From The Top' Comes To Bowdoin Feb. 29, Featured Events (Bowdoin)Документ2 страницы12.2.1 Bowdoin - Edu - NPR Show 'From The Top' Comes To Bowdoin Feb. 29, Featured Events (Bowdoin)allenwyuОценок пока нет

- 12.2.24 Orient - NPR's From The Top' To Record in Studzinski HallДокумент2 страницы12.2.24 Orient - NPR's From The Top' To Record in Studzinski HallallenwyuОценок пока нет

- NPR's From The Top Show 247 Press ReleaseДокумент2 страницыNPR's From The Top Show 247 Press ReleaseallenwyuОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5782)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (890)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Sightreadingintro StudentteachingДокумент2 страницыSightreadingintro Studentteachingapi-302485494Оценок пока нет

- Circle of Fifths PDFДокумент1 страницаCircle of Fifths PDFjimurgaОценок пока нет

- This Is My Wish (SATB)Документ13 страницThis Is My Wish (SATB)Steele1stPlace100% (4)

- Cooke - Sonatina - Flute PartДокумент5 страницCooke - Sonatina - Flute Partlotoazul200033% (3)

- (Cliqueapostilas - Com.br) Apostila de Clarinete 12Документ55 страниц(Cliqueapostilas - Com.br) Apostila de Clarinete 12Ileusis LunaОценок пока нет

- Preludes PHDДокумент177 страницPreludes PHDNemanja EgerićОценок пока нет

- Trick 1 - Fretboard MasteryДокумент1 страницаTrick 1 - Fretboard Masteryxalba14Оценок пока нет

- SOP Reader 3.0 - Version 2014Документ129 страницSOP Reader 3.0 - Version 2014Joy GohОценок пока нет

- Life Could Be A Dream-BassДокумент1 страницаLife Could Be A Dream-BassNicolas BernierОценок пока нет

- Ligeti Nonsense Madrigals and AtmospheresДокумент24 страницыLigeti Nonsense Madrigals and AtmospheresPaBlOsKiUs100% (1)

- EM - Wes Mus - T2 - G9 - I, II PP Ans - 2018Документ7 страницEM - Wes Mus - T2 - G9 - I, II PP Ans - 2018SAWANMEE PERERAОценок пока нет

- Piano Concerto No 1 Mvt. 3 - Felix Mendelssohn - WIP Solo Piano ArrangementДокумент6 страницPiano Concerto No 1 Mvt. 3 - Felix Mendelssohn - WIP Solo Piano ArrangementJCHACHURRAОценок пока нет

- Trombone Slide ChartДокумент1 страницаTrombone Slide ChartMatthew HarrisОценок пока нет

- Haydn - Piano Sonata No 29 in FДокумент10 страницHaydn - Piano Sonata No 29 in FDavide IncorvaiaОценок пока нет

- Stevie Wonder - The Great Songs of Stevie Wonder (Organ Arr)Документ44 страницыStevie Wonder - The Great Songs of Stevie Wonder (Organ Arr)Diogo DomicianoОценок пока нет

- Chorus All The Things You Are Solo2Документ3 страницыChorus All The Things You Are Solo2Olivier BlondelОценок пока нет

- Johann Strauss Flute Piece Features Amor MarshДокумент1 страницаJohann Strauss Flute Piece Features Amor MarshEnrico BozzanoОценок пока нет

- Bach Flute Partita Arranged for GuitarДокумент49 страницBach Flute Partita Arranged for GuitarMariaElonenОценок пока нет

- Feldbrill Catalogue - FINAL For Distribution - XLSX - Scores (Trevor)Документ69 страницFeldbrill Catalogue - FINAL For Distribution - XLSX - Scores (Trevor)Trevor WilsonОценок пока нет

- Lesson 25 - Greensleaves - Extra Left Hand NotesДокумент4 страницыLesson 25 - Greensleaves - Extra Left Hand NotesKunal AnandОценок пока нет

- Klinger ValseChopinДокумент5 страницKlinger ValseChopinCristiano Arata100% (1)

- Peace I Leave With YouДокумент2 страницыPeace I Leave With YouJasean YoungОценок пока нет

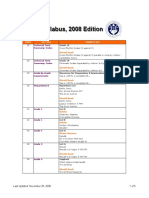

- Piano Syllabus, 2008 Edition Piano Syllabus, 2008 Edition: Section CorrectionДокумент5 страницPiano Syllabus, 2008 Edition Piano Syllabus, 2008 Edition: Section Correctionyongbak213Оценок пока нет

- Developing Chord FluencyДокумент2 страницыDeveloping Chord Fluencyremenant2006100% (1)

- You Only Cross My Mind in Winter: SopranoДокумент4 страницыYou Only Cross My Mind in Winter: SopranoDiego ZoccoОценок пока нет

- Boney M-Mary's Boy Child Oh My Lord 1Документ99 страницBoney M-Mary's Boy Child Oh My Lord 1Matthew Windsor50% (2)

- Dutilleux's Symphony No. 1 Explores Sonic EmergenceДокумент2 страницыDutilleux's Symphony No. 1 Explores Sonic EmergenceAlexander Klassen67% (3)

- Secondary UnitДокумент36 страницSecondary Unitapi-649553832Оценок пока нет

- Abrsm Aural (GRD 1 - 8)Документ8 страницAbrsm Aural (GRD 1 - 8)Andri Kurniawan100% (1)

- Bob Taylor - The Art of ImprovisationДокумент72 страницыBob Taylor - The Art of ImprovisationomnimusicoОценок пока нет