Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

All Shall Be Well, Really

Загружено:

John Sobert SylvestАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

All Shall Be Well, Really

Загружено:

John Sobert SylvestАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Most of us know how to behave in polite company, company like God, for example.

We piously affirm the creed and humbly acknowledge Who's in charge, but ...

Let's get real, though.

While we heartily sing along with our children that He's got the whole world in

His hands and believe every word of it and while we take great comfort in

knowing that what no eye has seen, ear heard nor the heart of wo/man ever

conceived, such are the things prepared for those who love the Lord , still ...

What we are able to truly abandon to providence is the whole world, in general, but not anything in our own lives, in particular?

While we trustfully surrender our sweet by and by to the vague notion that the Kingdom will come and His will will indeed be done, that trust is more firm regarding how it may be in heaven, then, in the distant future. We're not quite as confident, are we, regarding our concerns on earth, here and now?

So, we hedge our bets.

We hold on to some measure of our perfectionism, our pride (how we see ourselves), our prestige (how others see us, even living in their minds or letting them rent space in our heads), power, pleasure, pain avoidance and, most definitely, our profits (material things, mammon) and such, all as insurance for this vale of tears?

How and why is it that we may nurture a most blessed assurance regarding an afterlife even while all too often positively terrified about so many things in this life? And why does this terror seem to be amplified even as our joys begin to multiply? To be concrete, for many, perhaps even most, of us, those bundles of joy fomenting most of our anxiety are our children! This is not to exclude, however, our lack of emotional sobriety regarding our reputations, social status, political aspirations, jobs and/or careers, finances, or even athletic success (whether directly or vicariously, whether through our children or fandoms). Most definitely, we must unfortunately include what we suffer more insidiously through various process (gambling, overeating, social media) or relationship (infatuation, limerance, sexual objectification, even financial bondage)

addictions, and, more dangerously, through substance addictions (alcohol,

drugs), that destroy our health, imperil our own and others' lives or merely drain our focus and attention (and checking accounts) from more worthwhile aspirations or even essential goals. Codependence, for its part, is rooted in a belief that all will be decidedly unwell without our own pathetic overinvolvement.

When Julian of Norwich proclaims that all may, can, will and shall be well and

you will know that all manner of things will be well - what might be our practical

takeaway, here and now? How might that better invite and encourage our trustful surrender and abandonment to providence? Why did every angelic apparition in scripture commence with the celestial injunctive to fear not?

If, in our consolations regarding our ultimate concerns, we drastically differ from those (nowadays) too often celebrated, nihilistic existentialists, Nietzsche,

Sartre and Camus and even if we've journeyed out of the despairing world of Macbeth and have drawn deep inspiration from Dostoevsky's explorations of the abyss, still, we don't so easily escape a more practical nihilism regarding our more proximate concerns, do we?

And that's why religion so often has indeed been an opiate of the people, right alongside our other manifold and multiform addictions, disordered appetites and inordinate attachments, including those to ... you know, again ... our perfectionism, pride, prestige, power, pleasure, pain avoidance or profits, all this rather than to providence.

Even when all is well with my world, most of us are not unaware that all can be decidedly wrong with so much else of the world. Even as Jesus turned water into wine, enlivening a celebration and sparing a young couple embarrassment, He was not out of touch with the enormity of human pain and immensity of human suffering of which we remain so very poignantly aware, even in this new millennium?

Still, nowhere did Jesus answer Job's interrogators or the plaintive questions of the psalmists. Nowhere have philosophers and theologians satisfactorily resolved the theodicy problem of how an all powerful, all knowing, all good God can allow such suffering as experienced in our human condition. There have been some rationally successful solutions, to be sure, but none that are, finally, existentially satisfying, at least not in a universally compelling way.

Karl Rahner, in his very first sermon, observed that so many don't even confront such issues until a crisis overtakes them, personally, citing, as an example, how

millions of parents lose millions of children each and every year, never once questioning life's meaning before. Others of us, abundantly blessed in so very many ways, though, have indeed vicariously immersed ourselves in stories of the Russian gulags, Nazi holocaust or more recent African and Balkan genocides, not to mention the misfortunes visited on indigenous peoples worldwide, both intentionally and unintentionally, by colonizers.

If, as has been said, the glory of God is wo/man fully alive (St Irenaeus and others), God's realization of same has apparently fallen short? Again, perhaps this is more so an eschatological truth, a reality more there than here, more then than now?

Some observe, however, that many of our philosophical and theological quandaries derive from improperly framed questions. Such questions address the following categories of reality:

1) who is wo/man? the anthropological

2) how did all of this come about? the paterological (the Father, creator)

3) what is wrong and how to fix it? the soteriological

4) where's all of this finally headed? the eschatological

5) how do we get there? the ecclesiological

6) might there be a so-called outside assist? the pneumatological

(the Spirit)

7) why was there an incarnation? the christological

8) what return shall we make? the sophiological

These questions and categories are addressed at length throughout this site, all within the context of what I claim as my Eucharistic architectonic, which sees

the givers receiving (and re-gifting) the gifts given by reality's givers.

Basically, mine is a pervasively Franciscan view, radically incarnational, profusely pneumatological, catholically sacramental ...

Beginning with the question of what return shall we make, my sophiology draws nuanced distinctions that carefully distinguish the surrender of our human will (in terms of God-purposing) from any view that would consider theosis or divinization strictly in terms of human growth, development or potential. Theosis is, instead, more so in the provenance of Mary, our exemplar for divinization, and her succession of fiats, saying yes again and again and again, of the little man from Assisi, in his simplicity and poverty and perfect joy, of the Little

Flower, in her little Carmelite way, of Brother Lawrence and so many others,

who embraced all as revealed, even, to our little children. It's all there in the

Magnificat, in the prayer of St Francis ...

The Franciscan view is that the Christ was in the cards from the cosmic get-go and the incarnation was not otherwise occasioned, therefore, in response to any

felix culpa. To be clear, this is to claim that He was coming, anyway, no matter

what. God indeed so loved the world that S/he inhabited it, christologically and pneumatologically, as it was in the beginning, is now and forever shall be, ontological ruptures and soteriological efficacies (overcoming sin and death, providing healing) notwithstanding.

Our sophiological journey from image to likeness much more entails trust, surrender, fiat, cooperation, even much letting go and getting out the way, cultivating a strong freedom (from addictions, attachments) and a strong will, even, that is willing, however, not willful, that is God-purposed.

Indeed, then, this Franciscan, contemplative lens, which is what this site is all about, rigorously laying a foundation of philosophical theology that supports the hermeneutic of Richard Rohr, Brian McLaren, Thomas Merton ... Franciscan,

emergent, contemplative ... reformulates questions of suffering less so in

theoretic terms of theodicy and more so in performative terms of What am I

going to do about it?

The eschatological question does not address then over now but very much includes, rather, our proleptic or anticipatory realizations of Kingdom realities here and now and celebrates them as first fruits, an earnest, a down payment, a guarantee, in and by the Spirit of what and Whom will be gifted in the fullness of time, a kairos moment not chronos. These give us hope and good reason to trust more.

However much ours is a fragile human spirit, it is resilient. So many of the events we have imagined and worried about have never happened, even if unimaginable terrors have been visited on us, too. Even then, we learn to live

quite well with losses we never quite get over is also our universal human experience. When we older folks voice assurances that God gifts each of us with the grace sufficient for each day and for every cross, those are not empty words or pious mumblings but the fruit of long and actual experience (our own and that of people like Viktor Frankl, Corrie Ten Boom, Immaculee Ilibagiza). We can all testify, some more than others, to habits of worry that amounted to wasted time and squandered joy. A LOT of it, probably measured, moment by moment, cumulatively, in terms of YEARS! Whatever the case or source of our suffering, such stumbling blocks can indeed become stepping stones. All is invited for surrender to transformation that, as Willie Dixon says, the blues are

the roots, while the rest are the fruits. Pain not somehow transformed, says

Richard Rohr, we will somehow continue to transmit to others, often those whom we love the most and would least want to offend. The world's most beautiful poetry and other art forms are often pain transformed and consolations and healing received, paradoxically, when ministered to others.

We can attest to the truth that worry is nothing but the devil's form of meditation. We can point to scores of people, ourselves included, who've experienced all manner of loss and note that they do smile again, even laugh again, do live

again, even love again.

All may, can, will and shall be well, for those of little or of great faith (and no one

has no faith, as it is not the opposite of doubt but the other end of the same polar reality of our concerns regarding ultimates, realities about which we most deeply care). And you will know that all will be well. You do not have to wait until old age or even until you become a mystic.

We are often more terrified at the thought of being terrified, often more hurt from the idea of loss and pain, than from the actual loss and pain, itself, if indeed it does materialize, as some assuredly will in every life. Sufficient for the day, though, are the troubles and cares thereof, so, do not let your heart be troubled.

Thomas Merton reminded us that bad things are even likely to happen, even to good people. What the good news guarantees, instead, he says, is that the bad

shall never become the worst. And that IS true -not just in the other-worldly way,

which it is, but - NOW ... and ever shall be, world without end. Amen.

I once asked Phil St. Romain, best-selling Ligouri author and a true spiritual master, if he had a nutshell discernment approach. He responded rather easily with: If one can fill in the blank to the following statement, "I'll be okay when

________" then one has some sort of spiritual problem, be it large or small. I

believed that in my head 25 years ago, when he first said it over a whopper (maybe a whaler, it's okay if I get this wrong) at Burger King and, increasingly, I've come to better realize its truth in my bones.

Deep peace, great shalom and perfect joy ... St. Francis, pray for us!

John Sobert Sylvest on Scribd

Вам также может понравиться

- An Evolving God, An Evolving Purpose, An Evolving WorldОт EverandAn Evolving God, An Evolving Purpose, An Evolving WorldРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1)

- Imperative Life Questions of Truth and Consciousness: A Journey That Is Ever Changing...But Never EndingОт EverandImperative Life Questions of Truth and Consciousness: A Journey That Is Ever Changing...But Never EndingОценок пока нет

- What If Both Creationists And Atheists Evolutionists Are WrongОт EverandWhat If Both Creationists And Atheists Evolutionists Are WrongОценок пока нет

- The Zen of Hollywood: Using the Ancient Wisdom in Modern Movies to Create a Life Worthy of the Big Screen. Success Through Unity.: A Manual for Life, #4От EverandThe Zen of Hollywood: Using the Ancient Wisdom in Modern Movies to Create a Life Worthy of the Big Screen. Success Through Unity.: A Manual for Life, #4Оценок пока нет

- Good God - Catholicism and Secularism in The Modern WorldДокумент10 страницGood God - Catholicism and Secularism in The Modern WorldAlistair MurrayОценок пока нет

- Taking Down The Curtain: The Truth About Faith, Fact, and the Slippery Wizards of Voodoo MetaphysicsОт EverandTaking Down The Curtain: The Truth About Faith, Fact, and the Slippery Wizards of Voodoo MetaphysicsОценок пока нет

- Inhabiting Heaven NOW: The Answer to Every Moral Dilemma Ever PosedОт EverandInhabiting Heaven NOW: The Answer to Every Moral Dilemma Ever PosedОценок пока нет

- Raging with Compassion: Pastoral Responses to the Problem of EvilОт EverandRaging with Compassion: Pastoral Responses to the Problem of EvilРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (3)

- The Zen of Hollywood: Using the Ancient Wisdom in Modern Movies to Create a Life Worthy of the Big Screen. Karma, Giving, and Non-Attachment.: A Manual for Life, #5От EverandThe Zen of Hollywood: Using the Ancient Wisdom in Modern Movies to Create a Life Worthy of the Big Screen. Karma, Giving, and Non-Attachment.: A Manual for Life, #5Оценок пока нет

- The Zen of Hollywood: Using the Ancient Wisdom in Modern Movies to Create a Life Worthy of the Big Screen. Love Over Fear.: A Manual for Life, #2От EverandThe Zen of Hollywood: Using the Ancient Wisdom in Modern Movies to Create a Life Worthy of the Big Screen. Love Over Fear.: A Manual for Life, #2Оценок пока нет

- Evolving Life and Transition to the World Beyond: The Fantastic Journey of the Body, Mind and SpiritОт EverandEvolving Life and Transition to the World Beyond: The Fantastic Journey of the Body, Mind and SpiritОценок пока нет

- Walking on Water: Living into a New Way of ThinkingОт EverandWalking on Water: Living into a New Way of ThinkingОценок пока нет

- Creation? Evolution? Proof In Perception God's Time Is Not Our TimeОт EverandCreation? Evolution? Proof In Perception God's Time Is Not Our TimeОценок пока нет

- The Zen of Hollywood: Using the Ancient Wisdom in Modern Movies to Create a Life Worthy of the Big Screen. Powerful Thoughts and Beliefs.: A Manual for Life, #3От EverandThe Zen of Hollywood: Using the Ancient Wisdom in Modern Movies to Create a Life Worthy of the Big Screen. Powerful Thoughts and Beliefs.: A Manual for Life, #3Оценок пока нет

- Change Your World: Awakening to the Power of Truth – Beauty – Simplicity – ChangeОт EverandChange Your World: Awakening to the Power of Truth – Beauty – Simplicity – ChangeОценок пока нет

- The Age of Aquarius: Understanding the Meaning of the New World Changes and How God Wants Us to Live Our Spiritual AwakeningОт EverandThe Age of Aquarius: Understanding the Meaning of the New World Changes and How God Wants Us to Live Our Spiritual AwakeningРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Returning to Reality: Christian Platonism for Our TimesОт EverandReturning to Reality: Christian Platonism for Our TimesРейтинг: 5 из 5 звезд5/5 (1)

- Faith and Its Psychology (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)От EverandFaith and Its Psychology (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Оценок пока нет

- The Christ Is Not a Person: The Evolution of Consciousness and the Destiny of ManОт EverandThe Christ Is Not a Person: The Evolution of Consciousness and the Destiny of ManОценок пока нет

- It's Not Heaven Vs Hell That Needs To Be at Stake Vis A Vis TheДокумент10 страницIt's Not Heaven Vs Hell That Needs To Be at Stake Vis A Vis TheJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- The Art of Living & Dying Well: How to Extract the Nectar from Both FacesОт EverandThe Art of Living & Dying Well: How to Extract the Nectar from Both FacesОценок пока нет

- The Zen of Hollywood: Using the Ancient Wisdom in Modern Movies to Create a Life Worthy of the Big Screen. Authentic Living.: A Manual for Life, #1От EverandThe Zen of Hollywood: Using the Ancient Wisdom in Modern Movies to Create a Life Worthy of the Big Screen. Authentic Living.: A Manual for Life, #1Оценок пока нет

- World Without End: An Essay Re. Intention, Design, Endurance & Democracy—Volume OneОт EverandWorld Without End: An Essay Re. Intention, Design, Endurance & Democracy—Volume OneОценок пока нет

- The Transformation of (Y)Our World: Finding Optimism and Serenity During These Difficult TimesОт EverandThe Transformation of (Y)Our World: Finding Optimism and Serenity During These Difficult TimesОценок пока нет

- Tiny Little Boxes: How to Cope with Existential Dread by Way of Ice Cream and Other MeansОт EverandTiny Little Boxes: How to Cope with Existential Dread by Way of Ice Cream and Other MeansОценок пока нет

- Congenital Alterable Transmissible Asymmetry: The Spiritual Meaning of Disease and ScienceОт EverandCongenital Alterable Transmissible Asymmetry: The Spiritual Meaning of Disease and ScienceОценок пока нет

- How Can God Allow Such ThingsДокумент34 страницыHow Can God Allow Such ThingsVibhuti Dabrāl100% (1)

- Neochalcedonism - Contra Caricatures - Syncretistic CatholicismДокумент6 страницNeochalcedonism - Contra Caricatures - Syncretistic CatholicismJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Possible World & Free Choice Counterfactuals of Universalism - TДокумент5 страницPossible World & Free Choice Counterfactuals of Universalism - TJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Another Minority Soteriology - Syncretistic CatholicismДокумент6 страницAnother Minority Soteriology - Syncretistic CatholicismJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- A Goldilocks Eschatology - Hart's Human Potencies of Truth, GelpiДокумент7 страницA Goldilocks Eschatology - Hart's Human Potencies of Truth, GelpiJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- In Conversation With Brayden Dantin's "My Song Is Love UnknownДокумент4 страницыIn Conversation With Brayden Dantin's "My Song Is Love UnknownJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- More On My Subjunctive Apokatastasis & Indicative ApokatastenaiДокумент4 страницыMore On My Subjunctive Apokatastasis & Indicative ApokatastenaiJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Dear Universalists - What On Earth Are We Doing "Here" - SyncretДокумент8 страницDear Universalists - What On Earth Are We Doing "Here" - SyncretJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- A Cosmotheandric Universalism of ApokatastenaiДокумент3 442 страницыA Cosmotheandric Universalism of ApokatastenaiJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- A Defense of Double Agency - With A Goldilocks Account of DivineДокумент10 страницA Defense of Double Agency - With A Goldilocks Account of DivineJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Stitching Together Various Theo-Anthropo Threads - SyncretisticДокумент8 страницStitching Together Various Theo-Anthropo Threads - SyncretisticJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- We Should Critically Adapt Our Ontologies To Doctrine & Not ViceДокумент4 страницыWe Should Critically Adapt Our Ontologies To Doctrine & Not ViceJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Nature, Grace & Universalism - One Catholic Perspective - SyncreДокумент14 страницNature, Grace & Universalism - One Catholic Perspective - SyncreJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- If Universalism Is True, Then Why Weren't All Gifted The BeatifiДокумент7 страницIf Universalism Is True, Then Why Weren't All Gifted The BeatifiJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Beyond The Sophianic To The Neo-Chalcedonian - Actually, It's GoДокумент10 страницBeyond The Sophianic To The Neo-Chalcedonian - Actually, It's GoJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- A Field Guide To The Christs - Syncretistic CatholicismДокумент19 страницA Field Guide To The Christs - Syncretistic CatholicismJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Essences Don't Enhypostasize. They Are Enhypostasized. HypostaseДокумент2 страницыEssences Don't Enhypostasize. They Are Enhypostasized. HypostaseJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- How & Why Jenson's Right About What God Feels - Syncretistic CatДокумент15 страницHow & Why Jenson's Right About What God Feels - Syncretistic CatJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- A Universalist Appropriation of Franciscan Justification, SanctiДокумент14 страницA Universalist Appropriation of Franciscan Justification, SanctiJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Human Persons Can Be Divinized in A Perfectly Symmetric Way To HДокумент9 страницHuman Persons Can Be Divinized in A Perfectly Symmetric Way To HJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Responses To FR Rooney's Church Life Journal Series On IndicativДокумент25 страницResponses To FR Rooney's Church Life Journal Series On IndicativJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- The Apathetic Báñezian, Pathetic Calvinist, Sympathetic LubacianДокумент14 страницThe Apathetic Báñezian, Pathetic Calvinist, Sympathetic LubacianJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Grace Refers To Persons As They Intersubjectively Communicate inДокумент7 страницGrace Refers To Persons As They Intersubjectively Communicate inJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- The Full Maximian Apokatastases Monty - Immortality, Theotic RealДокумент5 страницThe Full Maximian Apokatastases Monty - Immortality, Theotic RealJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- A Cosmotheandric Universalism of ApokatastenaiДокумент3 442 страницыA Cosmotheandric Universalism of ApokatastenaiJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Why Beatific Contingency Is An Oxymoron - About Our Divine IndweДокумент13 страницWhy Beatific Contingency Is An Oxymoron - About Our Divine IndweJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Parallels Between Logical & Evidential Problems of Evil & of HelДокумент4 страницыParallels Between Logical & Evidential Problems of Evil & of HelJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Permission, Predestination, Peccability, Preterition, PredilectiДокумент7 страницPermission, Predestination, Peccability, Preterition, PredilectiJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- An Indicative Universal Sanctification & Subjunctive Universal IДокумент11 страницAn Indicative Universal Sanctification & Subjunctive Universal IJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- The Compatibilist Freedom of Apocatastasis & Libertarian AutonomДокумент2 страницыThe Compatibilist Freedom of Apocatastasis & Libertarian AutonomJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

- Our Search For A Continuity of Meaning Between Our Historical, PДокумент4 страницыOur Search For A Continuity of Meaning Between Our Historical, PJohn Sobert SylvestОценок пока нет

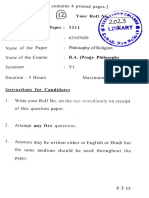

- B.A. (Prog.) Philosophy 6th Semester-2023Документ8 страницB.A. (Prog.) Philosophy 6th Semester-2023guptaaamit30Оценок пока нет

- Holtzman Livnat Islamic Theology PDFДокумент13 страницHoltzman Livnat Islamic Theology PDFAbu AbdelazeezОценок пока нет

- Jean-Luc Nancy-The Creation of The World or Globalization - State University of New York Press (2007)Документ137 страницJean-Luc Nancy-The Creation of The World or Globalization - State University of New York Press (2007)Marcelo Topuzian100% (1)

- Practice of The Presence of GodДокумент28 страницPractice of The Presence of GodPablo CarusОценок пока нет

- Yoga TamatrasДокумент39 страницYoga TamatrasRamasubramanian VenkateswaranОценок пока нет

- A Profound Mind by H. H. The Dalai Lama - ExcerptДокумент7 страницA Profound Mind by H. H. The Dalai Lama - ExcerptCrown Publishing Group50% (4)

- Evening Talks With Sri AurobindoДокумент203 страницыEvening Talks With Sri Aurobindoசுந்தர்ஜி ப்ரகாஷ்Оценок пока нет

- Banner of The Law (June - July) Chapter 1 - 10 PDFДокумент4 страницыBanner of The Law (June - July) Chapter 1 - 10 PDFarunОценок пока нет

- Timotheus Magazine 20Документ36 страницTimotheus Magazine 20Timotheus ProjectОценок пока нет

- 01 Does God ExistsДокумент2 страницы01 Does God Existsluke_0126Оценок пока нет

- Devil, The (II)Документ12 страницDevil, The (II)mcdozerОценок пока нет

- Islamic and Eastern Philosophers EducationДокумент2 страницыIslamic and Eastern Philosophers EducationSyafqhОценок пока нет

- Distinctive Features of This ThemeДокумент12 страницDistinctive Features of This ThemeMahnoor Ahmad100% (1)

- Individuality: Selections From The Agni Yoga Series Presented Before The Agni Yoga Society, October 21, 2008Документ4 страницыIndividuality: Selections From The Agni Yoga Series Presented Before The Agni Yoga Society, October 21, 2008shahriazОценок пока нет

- Adi Da enДокумент33 страницыAdi Da enmicha100% (2)

- Stamford Sai Center Bhajan Book April 2015 PDFДокумент1 744 страницыStamford Sai Center Bhajan Book April 2015 PDFDian AntariОценок пока нет

- Lord's PrayerДокумент1 страницаLord's PrayerOana CîmpanОценок пока нет

- Systematic Theology - Berkhof, Louis - Parte114Документ1 страницаSystematic Theology - Berkhof, Louis - Parte114Lester GonzalezОценок пока нет

- Sadr Al-Din Al-Qunawi As Seen From A Mevlevi Point of View, TakeshitaДокумент6 страницSadr Al-Din Al-Qunawi As Seen From A Mevlevi Point of View, TakeshitaaydogankОценок пока нет

- GAjendra PrayersДокумент4 страницыGAjendra PrayersAnna NightingaleОценок пока нет

- Gnanacheri: Sathguru Sri Sadasiva BramendrarДокумент5 страницGnanacheri: Sathguru Sri Sadasiva BramendrarAnand G100% (1)

- (D) Greek Philosophers View of The Human Person (The Sophists vs. Socrates)Документ14 страниц(D) Greek Philosophers View of The Human Person (The Sophists vs. Socrates)Mizu ChaeОценок пока нет

- The Story of Jan Darra: Utsana PhleungthamДокумент7 страницThe Story of Jan Darra: Utsana PhleungthamAlpesh Raj RajananadОценок пока нет

- Gurupadhuka Puja VidhiДокумент65 страницGurupadhuka Puja VidhiSai Ranganath B50% (2)

- Fundamental Option and Liberty of ChoiceДокумент8 страницFundamental Option and Liberty of Choiceivynegro100% (3)

- Vocabulary For The Glass Castle Word Illustration or ExampleДокумент2 страницыVocabulary For The Glass Castle Word Illustration or Exampleapi-63747439Оценок пока нет

- DeLanda - Space - Extensive and Intensive, Actual and VirtualДокумент5 страницDeLanda - Space - Extensive and Intensive, Actual and Virtualc0gОценок пока нет

- Umdat L Mutaabideen English by Shehu Uthman Ibn FuduyeДокумент155 страницUmdat L Mutaabideen English by Shehu Uthman Ibn FuduyeDawudIsrael1100% (1)

- The Ultimate Goal II PDFДокумент73 страницыThe Ultimate Goal II PDFhnif2009Оценок пока нет

- Esoteric Meaning of PinnochioДокумент14 страницEsoteric Meaning of Pinnochioadequatelatitude1715Оценок пока нет