Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

SSRN Id1975653

Загружено:

abcdef1985Оригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

SSRN Id1975653

Загружено:

abcdef1985Авторское право:

Доступные форматы

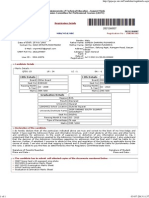

Vermont Law School

Faculty Accepted Paper

The Emerging Practice of Global Environmental Law

Professor of Law

Vermont Law School 164 Chelsea St. Box 96 South Royalton, VT 05068 tyang@vermontlaw.edu

Tseming Yang

Vermont Law School Paper #06-12

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1975653

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

The Emerging Practice of Global Environmental Law

Tseming Yang

Abstract Since the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment, ecological pressures on our planet have grown more acute. Yet, modern environmental law has also continued to evolve and spread within international as well as among national legal systems. With the paths of international and national environmental law becoming increasingly intertwined over the years, international environmental legal norms and principles are now penetrating deeper into national legal systems and environmental treaties are increasingly incorporating or referencing national legal norms and practices. The shifting legal landscape is also changing contemporary environmental law practice, creating greater needs for domestic environmental lawyers to be informed by international law and vice versa. This essay describes how domestic environmental law practice is increasingly informed by international legal norms, while the effective practice of international environmental law more and more requires enhanced awareness and even understanding of national environmental regulatory and governance systems. It illustrates these trends with the historical role and work of US EPAs Office of General Counsel. Key words: Global environmental law, environmental law practice, legal convergence

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1975653

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

The Emerging Practice of Global Environmental Law

Tseming Yang

Deputy General Counsel, US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, United States; on leave from Vermont Law School, South Royalton, VT, United States. Email: Yang.Tseming@epa.gov I am grateful for comments and assistance by Joseph Freedman, David Gravallese,Scott Hajost, Daniel Magraw, Diane McConkey, Katherine Nam, Jessica Scott, Russell Smith, Tom Swegle, and Steve Wolfson in the preparation of this essay. The views expressed in this essay do not necessarily represent the views of the US Environmental Protection Agency or the US Government.

Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1975653

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

1. INTRODUCTION With the 40th anniversary of the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment coming up in June 2012 and last years 40th anniversary of the United States (US) Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) just behind us, the launch of the journal Transnational Environmental Law is a timely development. As the paths of international and national environmental law have become increasingly intertwined, this new journal recognizes that description and analysis of the two fields in isolation fails to appreciate not only their reciprocal influence but also the rise of norms that are neither purely domestic nor international, but rather transnational and global in nature. The journal will provide an important forum to study the growth and expansion of what Robert Percival and I have referred to as the emergence of global environmental law.1 In this essay, I describe how some of these developments are becoming visible in contemporary environmental law practice, primarily from the perspective of an American government lawyer. The first part of this essay will describe how domestic environmental law practice is increasingly informed by international legal norms, and at times even foreign environmental norms, while the effective practice of international environmental law more and more requires enhanced awareness and even understanding of national environmental regulatory and governance systems. The second part of this essay will illustrate these propositions with the work of US EPAs Office of General Counsel (OGC). 2. GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL LAW Global environmental law appears to be the product of globalization, proliferation of international environmental instruments, development aid focused on the rule of law, and fundamentally similar public health and ecological needs transcending national borders. Across the earth, these pressures have prompted nations to develop and reform existing national and international environmental law systems. The associated convergence and integration trends have led to the ongoing crystallization of global environmental law -- a common set of environmental legal principles and norms in national, international, and transnational law that are utilized to protect the environment and public health as well as to manage and conserve natural resources.2 One example of a common and widely accepted global environmental norm is the environmental impact assessment (EIA) duty, which now can be found in the great majority of national environmental law systems, in many international environmental instruments, and even as a transboundary norm.3

See generally T. Yang & R.V. Percival, The Emergence of Global Environmental Law (2009) 36 Ecology Law Quarterly, pp 615-64. 2 Ibid.. 3 See generally ibid. For recent developments with respect to EIA as a transboundary duty, see the International Court of International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruling in Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay (Argentina v. Uruguay), para. 178-80 (Judgment of 20 Apr. 2010), available at http://www.icj-cij.org/docket/files/135/15877.pdf; case comment by C.R. Payne, Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay: The International Court of Justice Recognizes Environmental Impact Assessment as a Duty under International Law (2010) 14(9) American Society of International Law Insight, pp. 1-11; available at http://www.asil.org/insights100422.cfm.

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

In recent years, these developments have become increasingly relevant to the actual practice of environmental law. Adoption of new multilateral environmental agreements on subjects ranging from climate change to biodiversity to chemicals and fisheries, as well as subsidiary protocols, have expanded and transformed many environmental norms. In addition, enormous efforts of law reform, law transplantation, and harmonization of norms at the national level, have dramatically changed the regulatory landscape at the international, national and subnational level.4 Increasingly, delivery of effective environmental legal services, especially to clients operating in the global markets, requires not only a good understanding of US environmental law and regulations but also, at a minimum, awareness of international and relevant foreign environmental laws. Similarly, growing recognition that national regulatory systems, including those of developing countries and emerging economies, are crucial to the successful implementation of multilateral environmental agreements has created a similar need for international environmental lawyers with respect to national laws. In short, the divide between US and international environmental law, traditionally seen by American lawyers as distinct areas of law, has blurred significantly over the past couple of decades. 3. INTEGRATION AND CONVERGENCE IN THE PRACTICE OF INTERNATIONAL AND NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL LAW For the private bar providing legal services to multinational businesses, internationalization of its environmental practice has come slowly but steadily and with practical consequences for the bottom line. Globalization has increased international business transactions, thereby raising demand for associated legal services. Domestic lawyers have learned more about foreign environmental regulatory systems in order to enhance their ability to counsel on transactions as well as to manage unfamiliar legal exposure and risk that come with doing business in foreign jurisdictions. They are increasingly called upon to provide transnational legal services such as due diligence review of compliance by a potential foreign corporate merger partner or supply-chain contractors or to assist with potential litigation in foreign jurisdictions. For government lawyers and members of the regulatory compliance and enforcement bar, that shift has been more subtle. When I first became engaged in the practice of international environmental law as a government lawyer in the mid-1990s, the field was largely considered a specialty area within public international law, generally outside of the expertise (and relevant scope of practice) of US environmental lawyers. Conversely, international lawyers working on environmental treaties rarely ventured into the details of how environmental law and regulation worked within the US or other national systems, preferring to outsource such questions to domestic lawyers or to assume away its relevance for their work. In many respects, that is likely attributable to the dualistic system of the United States. Unlike in monistic countries, where international law and treaties automatically become part of the national legal order, the United States dualistic system often requires an additional step of legislative incorporation, Senate advice and consent under the US Constitutions treaty clause.5 The extra incorporation step has generally been applicable to environmental treaties because they

4

For example China, which started out with just a general environmental framework statute in 1989, has enacted around two dozen pollution and resource-related statutes. 5 US Constitution, Art. II, sec. 2, para.2, Art. VI, para. 2.

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

are usually deemed non-self-executing. Accordingly, the role of international environmental law per se used to be relatively insignificant for American environmental lawyers since Congressional legislation and agency regulation were usually necessary to create explicit operational requirements in statutes and regulation -- sources of law that are familiar and easily accessible to American lawyers. However, globalization of environmental law practice, penetration of international law norms and principles deep into national legal systems, incorporation of national legal norms and practice into treaties, and accelerating trends of integration and convergence have changed the legal landscape significantly. Direct practical effects on national law have increased, creating greater needs for domestic law practice to be informed by international law. One manifestation has been direct incorporation or reference of treaty requirements in national environmental laws. For example, the Marine Protection, Research, and Sanctuaries Act (MPRSA) explicitly calls on the EPA Administrator to apply standards and criteria binding upon the United States under the [London] Convention[6], including its Annexes, with respect to ocean dumping permit criteria, as long as statutory requirements are not relaxed.7 Title VI of the Clean Air Act (CAA), which implements the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer,8 goes one step further in qualifying some of its provisions with the phrase to the extent consistent with the Montreal Protocol. In case of conflict between the Acts stratospheric ozone provisions and the treaty, the more stringent provision shall govern.9 Thus, under the MPRSA, agency lawyers examine the evolving requirements of the London Convention and its Annexes in order to ensure that EPA regulatory requirements are at least as stringent as the relevant standards and criteria in the Convention. With regard to ozone depleting substances (ODS), both government lawyers and the private bar must understand not only the relevant provisions of the CAA and regulations promulgated by EPA but also the currently applicable requirements of the Montreal Protocol. Given the complexity of the international ODS phase-down scheme, broad coverage of many different ODS, and widely varying time tables, questions about the interaction of domestic and international requirements are not necessarily straight-forward. Conversely, rising levels of international environmental cooperative activity and growing linkages with national implementing activities have also created a greater need for international lawyers to become more familiar with the operation and requirements of national environmental law systems. Compliance monitoring is probably the most obvious. While some MEA commitments are framed explicitly as relatively easily observable international acts of national governments, increasingly, treaty obligations also reference actions at the national and subnational level enactment of legislation or regulations, engagement in best efforts to achieve environmental outcomes, or even control of private party behavior.

6

Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter; London (UK), 13 Nov. 1972, in force 30 Aug. 1975, available at: http://www.imo.org. 7 MPRSA, section 102(a), 33 U.S.C. 1412(a). 8 Montreal (Canada), 16 Sept. 1987, in force 1 Jan. 1989, available at: http://ozone.unep.org/new_site/en/montreal_protocol.php. 9 CAA section 614, 42 U.S.C. 7671m.

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

For example, even though heavily qualified and conditioned, commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)10 explicitly call on parties to take particular types of actions that are traditionally deemed to be domestic in nature, such as establishing protected areas, regulating or managing biological resources, and protecting ecosystems.11 Similarly, the requirements of the ozone treaties call on parties not only to adopt appropriate legislative and administrative measures12 but also to phase out or reduce the industrial production of various ozone-depleting substances.13 Compliance inquiries of these types face an additional set of challenges when they involve regulatory implementation activities and enforcement practices, including the appropriate exercise of enforcement discretion. For example, the 1994 North American Agreement on Environmental Cooperation (NAAEC)14 requires a party to effectively enforce its environmental laws and regulations through appropriate government action and subjects it to the Agreements Article 14 Submissions process.15 The agreement thus incorporates into an international agreement an activity that is primarily the subject of domestic regulatory agencies - effective enforcement of environmental laws. Examination of applicable legislative and regulatory text alone is insufficient for discerning compliance. An understanding of the actual regulatory implementation and enforcement practices is crucial. Increasing adoption of implementation monitoring and compliance management mechanisms in modern MEAs have made such inquiries even more important. When the national environmental laws and practices of countries with poorly developed legal and regulatory systems are implicated, such an inquiry becomes even more difficult. The wide gulf between law-on-the-books and law-in-action in the systems of many developing countries and emerging economies means that compliance evaluation requires an understanding of the effectiveness of national environmental governance the system of environmental laws, implementation mechanisms, institutional arrangements, and accountability and enforcement processes (including judicial and administrative review) necessary for effective environmental protection.16 The efforts by many developing countries and emerging economies in recent years to modernize their environmental laws, even adopting some of the worlds toughest environmental standards applied in the US and Europe, has consequently not disposed of the compliance question. Governance institutions in many such countries are still evolving and not as robust as in most of the industrialized world. As a result, implementation, enforcement and effectiveness of environmental laws and regulations remain a work-in-progress.

10

Convention on Biological Diversity, Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), 5 June 1992, in force 29 Dec. 1993, available at: http://www.cbd.int/convention/text. 11 Convention on Biological Diversity art. 8. 12 Art. 2(2)(b), Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer, Vienna (Austria), 22 Mar. 1985, in force 22 Sept. 1988, available at: http://ozone.unep.org. 13 Montreal Protocol passim. 14 US-Canada-Mexico, Sept. 14, 1994, available at: http://www.naaec.gc.ca. 15 Ibid., Art. 5(1). 16 In the past, attention and energy on international environmental issues has largely focused on the development of new legislation and norms. However, the experience in the past few decades has shown, especially in developing countries, that enactment of laws does not in itself ensure effective implementation and enforcement. See generally S. Fulton & A. Benjamin, Foundations of Sustainability (2011) 28(6) Environmental Forum, pp. 32-6.

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

These examples illustrate that one cannot take the effectiveness of legal norms, including commitments negotiated at the international level, for granted. Robust governance systems at the national level are indispensible for designing and effectively implementing MEAs and other international environmental commitments. These in turn will require the efforts of experienced environmental lawyers and regulators to share best practices, especially with regulators and lawyers in the developing world and emerging economies, in order to help strengthen national governance systems. Finally, national environmental laws and practice are themselves increasingly influencing MEAs and international law practice. For example, state practice influences the interpretation and application of MEAs as well as the emergence of new customary international law principles.17 And rapid development of national environmental governance systems across the globe, especially through transplantation and adoption of environmental law norms and regulatory mechanisms in developing countries and emerging economies, is driving the evolution and potential emergence of norms that could eventually come to be viewed as general principles of law. 4. ONE FACE OF GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL LAW PRACTICE: EPAS OFFICE OF GENERAL COUNSEL One illustration of the growing interconnection between national and international environmental law can be seen in the law practice of EPAs Office of General Counsel (OGC) as well as other agencies and organizations. For OGC, the practice of global environmental law entails a mix of domestic, international, and transnational environmental law work. Such a legal practice is still relatively uncommon, but it is spreading. It also illustrates how government lawyers who have traditionally focused primarily on US environmental law have had to acquire familiarity and expertise in international and transnational law as part of their evolving practice and client needs. The great majority of OGC work, consistent with the bulk of the Agencys overall work, focuses on domestic environmental issues. However, the international dimension of environmental issues has grown, and so has the Agencys involvement, including in Department of State-led negotiations of international environmental instruments and their implementation. The trend has been driven by the practical needs of supporting the international environmental interests of the United States and an evolving understanding of the adverse impacts on human health and environmental quality by pollution and irresponsible use of toxic chemicals outside of the United States as well as inside its own territory. For example, various studies indicate that transboundary movement of mercury emissions, persistent organic compounds and other pollutants from sources an ocean away contribute to the deposition of harmful pollutants in the United States.18 Even inappropriate application of pesticides to food

17

Art. 38, Statute of the International Court of Justice, available at: http://www.icjcij.org/documents/index.php?p1=4&p2=2&p3=0. 18 National Research Council, Global Sources of Local Pollution: An Assessment of Long-Range Transport of Key Air Pollutants to and from the United States (National Academies Press, 2010), at pp. 108-9, 117 (2010).

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

crops, use of toxic substances like lead paint to make childrens toys, or the manufacture of lawn mowers and other consumer products failing to conform with US emission standards can affect the United States when global commerce leads to their importation and sale to American consumers. Applying domestic environmental enforcement system to imports at ports and border crossings can be a first line of defense against some of these challenges. However, most are often more effectively addressed through international cooperative activities. With respect to environmental challenges that involve the global commons, such as the atmosphere or the oceans, international cooperation is vitally necessary to prevent national efforts from being undone by pollution elsewhere. The same is true for ecosystems that extend outside of the United States or migratory species that spend part of their life-cycle abroad. Apart from human and environmental benefits, environmental engagements with other governments and international organizations can also advance international cooperation and diplomacy more generally. By sharing its decades of experience in environmental law, science, engineering and health, and expertise in best environmental practices, EPA has built strong and positive relationships with governmental counterparts in other countries. Its broad commitment to public participation, environmental justice, and the rule of law resonates with environmental professionals and advocates throughout the world, helps build goodwill, and provides environmental leadership by example. When local or regional conflicts between polluters, pollution victims, and government agencies are reduced or competition for scarce natural resources is lessened, social and political stability is enhanced and global security is ultimately strengthened. Furthermore, sharing the lessons of the US experience and otherwise helping to build national environmental governance systems abroad can make pollution havens less likely to emerge and provides businesses operating globally with a more level playing field. Recognition of the interconnected nature of national interests in protecting human health and the environment and international environmental concerns motivated articulation of EPAs top international priorities in 2010, affirming the agencys long-standing commitment to international engagement.19 The Agencys commitment to building stronger environmental institutions and legal structures, primarily through bilateral technical assistance, is a direct recognition that ineffective environmental law and governance in other countries creates direct or indirect adverse consequences for the United States because it can hinder efforts to solve US environmental problems.20 These developments, especially proliferation of environmental agreements and environmental chapters of trade agreements, have greatly increased the need for associated legal counseling and support. Preparation of implementing legislation and regulations as well as counseling on how the ongoing activities of international organizations and multilateral

19

The priority areas laid out for the agency focused on: 1) Building stronger environmental institutions and legal structures, 2) Combating climate change by limiting pollutants, 3) Improving air quality, 4) Expanding access to clean water, 5) Reducing exposure to toxic chemicals, and 6) Cleaning up hazardous e-waste. Of course, work on a range of other international matters continues as well. 20 It is worth noting that environmental efforts by the developing world and emerging economies are as much, if not even primarily a response to increasing calls by their own citizens to address serious environmental challenges in the developing world, as they are responses to outside pressures.

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

environmental agreements affect the Agencys operations and obligations are just a few such needs. Beginning in 1989, OGC informally created an International Activities Division, formally launched in 1991. Prompted in part by the preparations for the 1992 Earth Summit and Administrator Bill Reillys particular interest in international environmental issues, the Divisions responsibilities and structure mirrored that of the other divisions within OGC, but focused on the international law needs of the Agency. It was then led by an Associate General Counsel and Deputy Associate General Counsel and included six staff attorneys. Like other law divisions within OGC, it reported directly to the General Counsel. Its function was then described as counseling EPA on international environmental law, including environmental agreements, to advance the Agencys international engagements as well as its domestic implementation activities. It also assisted EPA in interagency processes related to international environmental law and policy, contributing EPAs unique environmental and public health interests, experience, and mission to United States participation in the negotiation of international legal instruments at the bilateral, regional, and multilateral level as well as work in international organizations and meetings. OGCs International Activities Division was initially headed by Scott Hajost, a former senior lawyer from the State Departments Legal Advisors Office. After Hajost left EPA for the Environmental Defense Fund in 1990, leadership of the Division subsequently came from the legal academy, Professor Edith Brown Weiss of Georgetown Law School and her successor, former University of Colorado law professor Daniel Magraw, who became President of the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) in 2001. During the George W. Bush Administration, the International Environmental Law Office, as it was then named, shrunk in staff size and then, in 2008, was merged with another law office into a combined entity, the Cross Cutting Issues Law Office, headed by a single Associate General Counsel. There it remains a specialized practice group, the International Environmental Law Practice Group (IELPG), made up of four staff lawyers and its leader, an Assistant General Counsel. Further support comes from lawyers based in OGCs media law offices and Regional Counsels offices. The Agencys effort leadership to re-elevate OGCs international environmental law practice in 2010, under the Obama Administration, led to the appointment of a Deputy General Counsel to provide leadership for EPAs overall international environmental law needs. As a practical matter, that has required closely working with the IELPG as well as other practice areas with issues related to international environmental law. In its international work, OGC works closely with a number of internal client programs, such as the Office of International and Tribal Affairs,which generally coordinates international work within EPA and focuses on cross-cutting matters. OGC also works closely with individual media programs such as the Air and Radiation Office with regard to its work on international ozone depletion, transboundary air pollution, and climate change issues, the Office of Water with respect to ocean and other transboundary water pollution issues, and the Office of Solid Waste and Emergency Response regarding international hazardous waste trade issues. Externally, OGC works with the entire range of federal agencies involved in international issues, including the 9

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

Department of State, the US Trade Representatives Office, the Coast Guard, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the US Agency for International Development. In addition, OGC has assisted EPAs bilateral work with international organizations, such as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), as well as EPAs counterparts in other countries such as the Brazilian Ministry of the Environment and Chinas Ministry of Environmental Protection. OGCs present-day work continues its long-standing role of providing international environmental law expertise for the agencys activities. The bulk of OGCs international work, especially IELPGs, consists of counseling EPA on international environmental activities and representing its legal interest in interagency processes and international negotiations from the perspective of its particular public health and environmental mission. Such counseling is designed to ensure that the United States can take actions and make policy judgments with a sound appreciation of applicable international law principles and EPAs statutory authorities, Congressional mandates, and its distinct mission within the federal government to protect public health and the environment. Most counseling work arises in the context of ongoing multilateral negotiations, such as ongoing discussions to create a global legally-binding mercury treaty,21 or bilateral ones, such as efforts to revise the existing US-Canada Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement.22 Ensuring that new international commitments do not inappropriately conflict or otherwise hinder EPA in implementing its mission to protect human health and the environment, has been especially important in the context of international trade negotiations, such as a Transpacific Partnership designed to expand and liberalize trade among a number of Pacific nations.23 Since the TunaDolphin case under the WTOs predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), EPA has actively sought to ensure that new trade agreements do not adversely affect its domestic regulatory authority nor impair environment and public health. OGCs analysis in such situations helps determine whether new international commitments can be implemented under existing statutory or regulatory authority or whether new Congressional legislation or regulatory changes are needed. Particularly, when U.S. diplomats have made it a negotiation position that no new congressional authority will be sought for a new international instrument, possibly because obtaining new legislation might be a serious challenge, an understanding of existing domestic legal authority is crucial to steering international negotiations. Finally, OGCs work is crucial in the US implementation of international treaties, whether through regulatory revisions or by new legislation. Identification of legal authority gaps or needs for regulatory clarification allows for legislation and regulatory changes to be crafted. Some provisions in existing US environmental statutes anticipate future international

21

See for details on the mercury treaty negotiation process, e.g., http://www.unep.org/hazardoussubstances/Mercury/Negotiations/tabid/3320/Default.aspx 22 (Ottawa (Canada), 22 Nov. 1978, in force 22 Nov. 1978, superseding the 1972 Agreement, available at: http://www.epa.gov/greatlakes/glwqa/1978/index.html. 23 Further information available at: http://www.ustr.gov/tpp.

10

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

agreements.24 Oftentimes, however, existing statutory authorities are deemed to be insufficient for implementation of new agreements. In addition to providing counseling, OGC is also intimately involved in ensuring the Agencys compliance with international treaty commitments and defending it against allegations of non-compliance. Because some of the modern MEAs, such as the Montreal Protocol25 and the Kyoto Protocol,26 now contain mechanisms that seek to monitor and proactively manage noncompliance issues, such issues have grown in importance.27 As noted above, for example, article 14 of the NAAEC,28 the environmental side agreement to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA),29 allows private individuals to submit allegations that a NAFTA country has failed to comply with its commitment to effectively enforce its environmental laws. Potential remedies include an investigation and compilation of a factual record regarding the allegations.30 One pending submission, Coal-fired Power Plants,31 has alleged failures by the United States to effectively enforce the Clean Water Act (CWA)32 with respect to mercury releases. Analysis of the allegations has required examination of both US environmental law and US obligations under the NAAEC.33 Finally, OGC has also supported broader US diplomatic engagements and environmental leadership efforts globally including EPAs interest in building stronger environmental institutions and legal structures abroad. Such capacity-building work has included hosting and participating in workshops sharing the American environmental law experience with foreign government officials and other foreign visitors to EPA each year. Beyond enhancing protection of the global environment by strengthening environmental governance abroad, such efforts also advance democratic governance and the rule of law worldwide.34 In recent years, EPA has worked with the US Agency for International Development (USAID) to engage in capacity-building efforts in Central America under the US-Central America-Dominican Republic Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR).35 The objective has been to

24 25

See, e.g., the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), section 3017, 42 U.S.C. 6938. N. 8 above. 26 Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Kyoto (Japan), 10 Dec. 1997, in force 16 Feb. 2005, available at: http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/items/2830.php. 27 See generally T. Yang, International Treaty Enforcement as a Public Good: The Role of Institutional Deterrent Sanctions in International Environmental Agreements (2006) 27 Michigan Journal of International Law, pp. 1131. 28 N. 15 above. 29 San Antonio, TX (US), 17 Dec. 1992, in force 1 Jan. 1994, available at: http://www.nafta-sec-alena.org. 30 Arts. 5, 14 NAFTA, ibid. 31 Coal-fired Power Plants, SEM-04-005, filed 16 September 2004, available at: http://cec.org/Page.asp?PageID=2001&ContentID=2390&SiteNodeID=544&BL_ExpandID. 32 CWA, 33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq. 33 Another submission, Logging Rider, raised the question of whether Congressional legislation limiting administrative review falls within the scope of the effective enforcement provision and thus could give rise to an investigation and factual record. See Logging Rider, SEM-95-002, filed 30 Aug. 1995, available at: http://cec.org/Page.asp?PageID=2001&ContentID=2345&SiteNodeID=545&BL_ExpandID. 34 For further elaboration on the close connection between effective environmental governance and the rule of law, see n. 16 above. 35 Washington, DC (US), 5 Aug. 2004, available at: http://www.ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-tradeagreements/cafta-dr-dominican-republic-central-america-fta.

11

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

develop and implement a model wastewater pollution control regulation for the region. As an outgrowth of the Environmental Cooperation Agreement (ECA)36 that the Parties signed as an adjunct to CAFTA, the project fostered regional harmonization of the domestic legal and regulatory regimes in each country with the goal of controlling wastewater discharges to surface waters. Together with Central American officials, a multi-disciplinary EPA team, which included OGC lawyers, prepared a model law that was adopted by the Environment Ministers of the participating countries by way of an agreement that the regulation would form the basis for national implementing legislation. Currently, EPA is working with individual Central American countries to integrate the model regulation into their specific legal and regulatory regimes.37 Of course, EPAs OGC is not alone among US federal government agencies in experiencing globalization of its environmental law practice. Notable is the Department of Justice (DOJ), which in recent years has acquired an international component in its prosecutorial work through the Lacey Act38and the Act to Prevent Pollution from Ships (APPS).39 The Lacey Act has, for several decades, made it illegal to import, export, transport, sell, receive, acquire, or purchase in interstate or foreign commerce any fish or wildlife that has been taken, possessed, transported, or sold in violation of federal, state, tribal or foreign law.40 Through amendments enacted in 2008, that prohibition was extended to plants and plant products taken, possessed, transported or sold in violation of federal, state, tribal, or foreign laws that protect plants. By referencing foreign law, the Lacey Act makes foreign legal prohibitions regarding fish, wildlife, and plant acquisition and commerce an element of US criminal prohibitions. As a result, the Act can be used as a tool for helping to conserve wildlife, fish and plants regardless of international borders. It also helps to ensure that trafficking in products illegally taken in other countries, such as wood products made from illegally harvested timber, does not undercut law-abiding U.S. companies who trade in legal forest products. For example, fishing by US commercial fishermen for albacore tuna off the coast of Mexico without the necessary Mexican permits led to arrest and guilty pleas under the Lacey Act recently.41 There is no doubt that the Lacey Act is still unusual, requiring federal environmental prosecutors not only to possess expertise in US environmental laws but also calling on them to gain an understanding of foreign law requirements regarding acquisition and commerce of natural resources. Introduction of legal expert testimony regarding the requirements foreign

36

Washington, DC (US), 18 Feb. 2005, available at: http://www.caftadrenvironment.org/left_menu/Environmental_Cooperation_Agreement.pdf 37 US AID has recognized EPAs effort with its Central American counterparts in developing the model wastewater pollution control regulation as an example of effective environmental capacity building and as a model for other environmental capacity building efforts, with tangible results: adoption by the Environment Ministers of the model regulation in principle and their effort to integrate it into and implement it in domestic legal regimes in individual countries. 38 16 U.S.C. 3371-3378. 39 33 U.S.C. 1901-1915. 40 16 U.S.C. 3372(a). 41 US Department of Justice, News Release: Commercial Fishermen Plead Guilty to Illegal Fishing and Shooting of Marine Mammals (June 28, 2011), available at: http://www.justice.gov/usao/cas/press/cas11-0628-

TwoCaptains.pdf.

12

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

environmental laws has not been uncommon in such cases and is advancing the practice of global environmental law even among federal prosecutors. The APPS also incorporates non-federal law norms, specifically prohibitions against waste disposal from ships, as set out in the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL).42 For example, a 2006 prosecution under the APPS for violation of MARPOL prohibitions against discharge of oil-contaminated waste resulted in a $37 million penalty against one shipping company.43 While both statutes are unusual in their reference to or incorporation of foreign and international norms, they are targeted at one of the fundamental challenges of international environmental problems limited jurisdictional reach of most environmental laws even though environmental problems are increasingly transnational and global in nature. The design of these statutes overcomes some of these challenges. Beyond the federal government, there are also increasing occasions for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the private sector to be engaged in the practice of global environmental law. Counseling on the implications of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA)44 for the environmental activities abroad of US-based corporations, including the interactions of such businesses with foreign environmental regulators and other government officials, appears to be significant. Similarly, private firms are increasingly engaged in investorstate dispute processes, such as under Chapter 11 of NAFTA, involving environmental issues. And environmental NGOs are increasingly utilizing fora such as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR)45 to raise environmental claims or tools such as the Alien Tort Claims Act (ATCA)46 to bring environmental human rights issues before American courts. Examples of such instances are growing, and we can expect that trend to continue and accelerate in the coming years. 5. CONCLUSION In the past, international and national environmental law were often thought of as parallel systems, largely independent of each other. However, for some years now, there has been a trend for international frameworks to increasingly reference national legal norms and for national systems more and more to incorporate international norms. The evolving practice of environmental law described here illustrates how the growing interlinkage between national and international legal systems and norms is put into operation. For environmentalists, the interconnectedness of the environment is a tenet that has connected the global to the local and the foreign to the domestic environment. Todays emerging

42

London (UK), 2 Nov. 1973, in force only after the 1978 London Protocol on 2 Oct. 1983, available at: http://www.imo.org/about/conventions/listofconventions/pages/international-convention-for-the-prevention-ofpollution-from-ships-(marpol).aspx. 43 US Department of Justice, News Release: Overseas Shipholding Group Inc. Will Pay Largest-Ever Penalty for Concealing Vessel Pollution, available at: http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2006/December/06_opa_849.html. 44 15 U.S.C. 78dd et seq. 45 See at: http://www.cidh.oas.org. 46 28 U.S.C. 1350.

13

Forthcoming in Transnational Environmental Law

12-20-2011

practice of global environmental law demonstrates that this fundamental axiom applies not only to the physical environment but increasingly our environmental regulatory and governance systems humanitys institutional environment.

14

Вам также может понравиться

- Fundamental Analysis Training Certificate for Jaimish ChampaneriДокумент1 страницаFundamental Analysis Training Certificate for Jaimish Champaneriabcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- Gujacpc - Nic.in Candidate Regdetails NishantДокумент1 страницаGujacpc - Nic.in Candidate Regdetails Nishantabcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- SSRN Id2179030Документ47 страницSSRN Id2179030abcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- Atul LTD 1Документ8 страницAtul LTD 1abcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- Supplymentary NotesДокумент68 страницSupplymentary Notessharktale2828100% (1)

- 33Документ32 страницы33paritosh7_886026Оценок пока нет

- Paper IДокумент19 страницPaper IPallavi PahujaОценок пока нет

- GtuДокумент3 страницыGtujigyesh29Оценок пока нет

- Gujarat Technological University: Practical Examinations of MBA ProgrammeДокумент1 страницаGujarat Technological University: Practical Examinations of MBA Programmeabcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- Finance, Comparative Advantage, and Resource Allocation: Policy Research Working Paper 6111Документ37 страницFinance, Comparative Advantage, and Resource Allocation: Policy Research Working Paper 6111abcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- Sales and Distribution MGTДокумент89 страницSales and Distribution MGTNitin MahindrooОценок пока нет

- Research Methods For ManagementДокумент176 страницResearch Methods For Managementrajanityagi23Оценок пока нет

- Paper-Iii Commerce: Signature and Name of InvigilatorДокумент32 страницыPaper-Iii Commerce: Signature and Name of Invigilator9915098249Оценок пока нет

- Advertisement LetterДокумент1 страницаAdvertisement Letterscribe03Оценок пока нет

- Correcting Real Exchange Rate Misalignment: Policy Research Working Paper 6045Документ48 страницCorrecting Real Exchange Rate Misalignment: Policy Research Working Paper 6045abcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- Gujacpc - Nic.in Candidate Regdetails NishantДокумент1 страницаGujacpc - Nic.in Candidate Regdetails Nishantabcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- NLДокумент8 страницNLabcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- Gujacpc - Nic.in Candidate Regdetails VinayДокумент1 страницаGujacpc - Nic.in Candidate Regdetails Vinayabcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- CEP Discussion Paper No 1121 February 2012 Why Has China Grown So Fast? The Role of International Technology Transfer John Van Reenen and Linda YuehДокумент27 страницCEP Discussion Paper No 1121 February 2012 Why Has China Grown So Fast? The Role of International Technology Transfer John Van Reenen and Linda Yuehabcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- Bstract: Setting The Stage For Reforms, Provides A Framework That Spells Out Key Areas of ReformДокумент1 страницаBstract: Setting The Stage For Reforms, Provides A Framework That Spells Out Key Areas of Reformabcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- Effect of Product Patents On The Indian Pharmaceutical IndustryДокумент105 страницEffect of Product Patents On The Indian Pharmaceutical Industryabcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- Effect of Product Patents On The Indian Pharmaceutical IndustryДокумент105 страницEffect of Product Patents On The Indian Pharmaceutical Industryabcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- PEFA2010Документ134 страницыPEFA2010abcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- On Dividend Restrictions and The Collapse of The Interbank MarketДокумент22 страницыOn Dividend Restrictions and The Collapse of The Interbank Marketabcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- OP002Документ44 страницыOP002abcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- OP001Документ19 страницOP001abcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- OP005Документ19 страницOP005abcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- OP008Документ16 страницOP008abcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- OP006Документ28 страницOP006abcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- OP009Документ31 страницаOP009abcdef1985Оценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- LAW 510 Public International Law IДокумент37 страницLAW 510 Public International Law IMastura Asri100% (1)

- Lsidyv 3 e 2542 EcДокумент1 104 страницыLsidyv 3 e 2542 EcAfan AbazovićОценок пока нет

- Commonwealth Constitutional Law - ANU - NotesДокумент31 страницаCommonwealth Constitutional Law - ANU - NotesSheng NgОценок пока нет

- Note On Udhr, Iccpr, IcescДокумент19 страницNote On Udhr, Iccpr, IcescShourov Roy MithuОценок пока нет

- Long Quiz in Ls 26Документ4 страницыLong Quiz in Ls 26Emmanuel Jimenez-Bacud, CSE-Professional,BA-MA Pol SciОценок пока нет

- Keeping The Republic Power and Citizenship in American Politics The Essentials 8th Edition Barbour Test BankДокумент24 страницыKeeping The Republic Power and Citizenship in American Politics The Essentials 8th Edition Barbour Test Bankjeromescottxwtiaqgrem100% (27)

- Digest - G.R. No. 118295 Tanada V Angara (Economy)Документ8 страницDigest - G.R. No. 118295 Tanada V Angara (Economy)MarkОценок пока нет

- Food Industry Recall ProtocolДокумент56 страницFood Industry Recall Protocolarta sinatraОценок пока нет

- Anuj Garg CaseДокумент15 страницAnuj Garg CaseKarthika VijayakumarОценок пока нет

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitДокумент16 страницUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsОценок пока нет

- Guidance on Delay, Disruption and AccelerationДокумент1 страницаGuidance on Delay, Disruption and AccelerationElmo CharlesОценок пока нет

- A cn4 507Документ109 страницA cn4 507amallaОценок пока нет

- 1856 General Treaty Between Morocco and Great BritainДокумент36 страниц1856 General Treaty Between Morocco and Great BritainMike Jones100% (8)

- Australian Legal SystemДокумент29 страницAustralian Legal Systembacharnaja100% (1)

- Outline - Con Law War PowersДокумент9 страницOutline - Con Law War PowersvatoamigoОценок пока нет

- PIL, Amen TayeДокумент71 страницаPIL, Amen Tayeprimhaile assefa100% (2)

- Public International Law Comprehensive Notes If You Are Taught by Prof. Raman of JGLS StudentДокумент77 страницPublic International Law Comprehensive Notes If You Are Taught by Prof. Raman of JGLS StudentJGLS studentОценок пока нет

- Repatriation and Reintergration of Liberian Refugees From Buduburam Camp, Ghana To Liberia: A Case StudyДокумент122 страницыRepatriation and Reintergration of Liberian Refugees From Buduburam Camp, Ghana To Liberia: A Case StudyGODSON BILL OCLOO100% (1)

- The Abidjan Convention Articles - EngДокумент13 страницThe Abidjan Convention Articles - EngPatrickОценок пока нет

- Asylum Case Colombia v. PeruДокумент7 страницAsylum Case Colombia v. PeruGrachelle AnnОценок пока нет

- Unesco BДокумент8 страницUnesco BBornes VancouverОценок пока нет

- Legal & Non-Legal Responses to Child SoldiersДокумент2 страницыLegal & Non-Legal Responses to Child SoldiersSushan NeavОценок пока нет

- 3.1 Customary International Law - UDHRДокумент17 страниц3.1 Customary International Law - UDHRNancy RamirezОценок пока нет

- Death Penalty, Civil and Political Rights, ICCPR: HUMAN RIGHTS Atty. Cervantes-PocoДокумент15 страницDeath Penalty, Civil and Political Rights, ICCPR: HUMAN RIGHTS Atty. Cervantes-PocopdasilvaОценок пока нет

- Common Article 3Документ37 страницCommon Article 3Anonymous tyEGT2RJJUОценок пока нет

- SC upholds constitutionality of Visiting Forces AgreementДокумент1 страницаSC upholds constitutionality of Visiting Forces AgreementRogel Exequiel TalagtagОценок пока нет

- National InterestsДокумент6 страницNational InterestsWaqas SaeedОценок пока нет

- PIL General PrinciplesДокумент7 страницPIL General PrinciplesRhoda VillalobosОценок пока нет

- CRCДокумент156 страницCRCLara Yulo100% (1)

- The Double Criminality Rule Revisited PDFДокумент14 страницThe Double Criminality Rule Revisited PDFAnantHimanshuEkkaОценок пока нет