Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

The Accountability of School Governing Bodies

Загружено:

Indra ManiamОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Accountability of School Governing Bodies

Загружено:

Indra ManiamАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

The Accountability of School Governing Bodies

Catherine M. Farrell and Jennifer Law

, University of Glamorgan Business School, Pontypridd CF37 1DL, tel. (01443) 482308, email = cfarrell@glam.ac.uk. Paper delivered at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference September 1997 No part of this paper may be reproduced or cited without permission. The Accountability of School Governing Bodies Abstract The notion of accountability has been central to the reforms which have been introduced in education since the Education Reform Act 1988. Government reforms have devolved key responsibilities from local education authorities to governing bodies within schools in England and Wales. Whilst these bodies are now accountable for many aspects of education provision, it is not clear how this works in practice. The aim of the paper is to identify the nature of the accountability of school governing bodies. The research will involve interviews with members of a range of these bodies to determine both how they perceive themselves to be accountable and how it operates in reality. Conclusions are drawn on the nature and effectiveness of governing body accountability. Key words: accountability, school governing bodies. Introduction Since the early 1980s there have been major changes in the governance of education. One of the most important reforms was the devolution of a number of responsibilities from the Local Education Authority (LEA) to individual school governing bodies. The aim of these changes was "to put governing bodies and headteachers under the greater pressure of public accountability, for better standards and to increase their freedom....It is that combination of unpaid but increasingly experienced governors and senior professional staff that is best placed to identify what is required" (DES, 1992:18). The clear assumption in this statement is that governing bodies would be better able, both to manage and be accountable than LEAs. This paper concentrates on the issue of governing body accountability and provides an initial analysis of the perceptions and practice of

governing body accountability. Who do governors feel accountable to and how does this operate in practice? Section one examines the legal changes in the accountability of governing bodies. Section two analyses the concept of educational accountability and in section three we examine the evidence on the operation of governing body accountability. Section four presents the findings from our research. These are evaluated in section five. Conclusions are drawn on the nature and effectiveness of governing body accountability. I. Legislative Reform The Education Act 1980 made it compulsory for each school in England and Wales to have a governing body. Before the Act, governing bodies did not exist in all schools. The legislation also established the need to include parental and teacher representation on each body. Tomlinson (1993) argues that this legislation was driven partly by a desire to promote local accountability in schools. Two further pieces of legislation greatly reformed governing bodies - the 1986 and 1988 Education Acts. The 1986 Act changed the constitution of governing bodies and the 1988 legislation significantly empowered them and enhanced their role. The reconstituted governing bodies allowed a greater role for individuals, such as those involved in business and industry and parents. This meant a reduced LEA and trade union representation on governing bodies. In terms of representation, parents and co-opted interests have numerical dominance on governing bodies. Both parent and teacher representatives are elected with additional members co-opted to the body. The membership of governing bodies is determined by a broad formula related to the enrolment number of a school. The 1986 Act also made it a requirement for Governors publish an annual report and to arrange a meeting of all parents. Beckett et al (1991:98) argues that the purpose of both of these initiatives was the drive to enhance accountability: "to provide a forum of accountability for the governing body, the head and the LEA, to make each of the partners in managing the school accountable to parents for their stewardship of it". The Education Act 1988, and subsequent legislative reform, empowered governing bodies in relation to the management of individual schools. School governing bodies now have extensive powers in relation to the admission and exclusion of pupils, budgetary responsibilities, hiring and firing of staff and the determination of headteacher salary levels. The governing bodies of GM schools have further powers since they are the official employer of those working within the school. School governing bodies have legal responsibilities to LEAs, Inspection authorities and to parents. In relation to LEAs, governors are legally obliged to provide the LEA (and the Secretary of State) with any relevant information or reports about its school and the work of the governing body that the LEA requires. A written statement of its aims for the curriculum and of any modification to the LEA's policy has to be provided (Welsh Office 1993). It must report to the LEA details

about the number of children have exceptions from the curriculum and those who have special educational needs. Governors must also provide the LEA with their policy on sex education and the arrangements within the school for collective worship. The governing body is financially responsible to the LEA for its decisions relating to expenditure within the school and for keeping accurate accounts. Accurate attendance registers must also be kept and where pupil attendance is low, the governing body are obliged to report this to the LEA. Following the Education (Schools) Act 1992, governors also have responsibilities within the area of school inspection. In general, governing bodies are responsible for the provision of relevant information to inspection authorities, for the distribution of the inspection report to parents and for taking appropriate action following the inspection. Parents must be informed of the inspection arrangements and be invited to a meeting with the school inspection team. Governing bodies are also obliged to provide specific information to parents. These demands are the provision of a prospectus and an annual report. The prospectus must include details relating to the curriculum policy of the school and complaints procedures, for example. The annual report includes information relating to the membership of the Governing Body, the election of parent governor information, financial information, examination and performance details. The governing body must also hold an annual meeting for parents. The governors are responsible for conducting the meeting. It provides the forum for parents to discuss specific questions and concerns arising from the annual report and to raise other issues about the school with the governors. Governing body accountability is a two way process. In addition to its accountability to the LEA and to parents, the headteacher is accountable to the governing body. The headteacher must supply the governing body with any relevant information which it requests. Headteachers, entitled to attend all meetings, are usually a full member of the governing body. Each meeting of the governing body will normally include the headteacher's report to governors. II. The Concept of Accountability Accountability is recognised to be a complex and difficult concept (Day and Klein 1987). A simple description is that to be accountable is to be required to explain or justify ones actions or behaviour. Hence the concept of accountability is closely connected to responsibility, as those who have been given responsibilities are asked to account for their performance. Stewart (1984:15) suggests that accountability is made up of two parts, the 'element of account' and the 'holding to account'. The element of account is the "need for information, including the right to question, and debate that information as a basis for forming judgements". In giving an account of performance, information is provided which may be verbal or written, formal or informal and may or may not be governed by strict rules. However, accountability

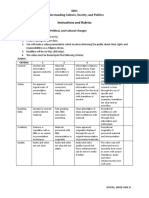

involves more than simply giving an account. The information will be evaluated, performance assessed and if it is not satisfactory then action may be taken. The capacity for action and potential to impose sanctions is what Stewart (1984) calls the element of holding to account. Dunsire (1978:41) also argues that this is important "the answer when given, or the account when rendered, is to be evaluated by the superior body, measured against some standard or some expectation, and the difference noted; and then praise or blame to be meted out or sanctions applied. It is the coupling of information with its evaluation and application of sanctions that gives 'accountability' or 'answerability' or 'responsibility' their full sense is ordinary organisational usage". One of the pre-requisites of effective accountability is that those given responsibility know whom they are responsible to, and for what aspect of performance. Similarly, those who delegate authority know whom to hold to account. Stewart (1984:16) argues that "the relationship of accountability, involving both the account and the holding to account can be analysed as a bond linking the one who accounts and is held to account, to the one who holds to account. For accountability to be clear and enforceable the bond must be clear". In addition to clarity there also needs to be agreement on the process and content of the account. Day and Klein (1987:5) state that accountability "presupposes agreement both about what constitutes an acceptable performance and about the language of justification to be used by actors in defending their conduct". Accountability is straightforward in circumstances when a simple task has been delegated to an individual however, it becomes more difficult when the services or tasks are complex and greater numbers of individuals are involved. As public services have become more complex political accountability appears to work less well. Political accountability operates when the general public hold their representatives to account for their performance. For this model of accountability to work, those representatives must be able to hold the service deliverers to account. However, this is difficult in services which are provided by professionals, as their organisational power enables them to resist attempts to measure the outputs of services provided (Day and Klein 1987). There are a number of models of accountability in education developed in the literature, which specify who is accountable, to whom and for what aspect of performance (for example Kogan 1986, Ranson 1986). Whilst there is an implicit role for the governing body in some of these models, none of them fully consider how the governing body as a whole, or the individuals within it are to be accountable. The table below provides a summary of these models. Table 1. Models of Educational Accountability

The professional model emphasises accountability for the process of education. This is generally secured through accounting to other professionals through such mechanisms as self-evaluation and inspections. Whilst there are some professionals on the governing body, the emphasis is the professional model is on accountability 'sideways' to other professionals, rather than upwards to the governing body. In the contractual model, accountability is exercised through the hierarchy, through the contract of employment and the democratic process. The education reforms since 1988 have devolved many responsibilities from LEAs down the hierarchy to governing bodies, so accountability through the democratic process has been reduced. The governing body forms part of the education hierarchy, but it is unclear who they account to and what mechanisms they use. Recent Conservative Governments have introduced a market approach to accountability. This has involved an emphasis on accountability for results to the consumers, who are given the opportunity to take their custom elsewhere. In this model, the governing body accounts to its customers through information on examination results and truancy rates. The final model is public accountability. This method of accounting stresses the role of parents and the wider community in determining the purpose and process of schooling. The emphasis is on citizens, rather than consumers and mutual accountability and partnership between the groups involved (Ranson, 1986; Sallis, 1988). The governing body may be involved in stimulating this parental and community involvement. III. The Accountability of Governing Bodies There is little evidence from the literature about the effectiveness of the practice of school governing body accountability, or the perceptions of the individuals who are accountable. There is a suggestion however, that "governing bodies are not particularly accountable" (Deem et al 1995:38). Many, (for example, Levacic, 1995 and Boyett and Finlay, 1996), argue that recent Conservative Governments have promoted an approach in which the school governing body fits a model of

accountability of a board of directors. Boyett and Finlay (1996:32) suggest that "in this instance however the 'shareholders' were depicted as the parents. Just like company boards, governing bodies were now required to produce an annual report for their 'shareholders' and to hold an annual general meeting, where the governors were visibly accountable to the parents for their actions over the previous year". In practice however, official guidance to school governors can be confusing. The Department for Education and Employment included a fairly wide definition arguing that governing bodies are "accountable to those who established and fund the school and also to parents and the wider local community for the way it carries out its functions" (DfEE 1996:5). In contrast, the Audit Commission and OFSTED (1995:4) focuses only on parents, describing the accountability of governing bodies as "making sure that parents are kept informed about what is happening in the school and that their views are taken into account". Levacic (1995) argues that the government expectations of governing bodies fit the accountable model provided by Kogan et al (1984). The accountable model is based on the premise that the governing body exists to control the activities of the school. Accountability is a central feature of this type of governing body accountability to all those who have an interest in the school and its activities. There is a perception amongst governors that they have an obligation to account for the way in which the school is performing. Mechanisms of accountability, such as the annual report, are stressed by this type of governing body. The chair of the governing body has a crucial role in securing consensus amongst all individual governors - chair acts as a de facto Chief Executive of the school. A close and trusting relationship with the headteacher is essential. Kogan et al (1984) provide three other models of governing bodies: the advisory, the supportive and the mediating governing body. In the advisory model, the purpose of the governing body is to "provide a forum in which school activities are reported to the laity and tested against their ideas about what the school should be doing" (Kogan et al 1984:151). For the role of the governing body to be effective, the governors must have the authority to be able to call the school to account. The school, through the headteacher, is obliged to inform the governing body of its actions and the reasons behind them. The views of the governors must be considered in the school's operation. As argued by Kogan et al (1984:151) "there must be a degree of give-and-take, for an advisory relationship rapidly becomes meaningless if the advice is never taken". According to Kogan et al (1984), the advisory governing body is professionally led. The supportive model, whilst centred on the activities of the school, is outward in terms of influencing the activities of other bodies. Its purpose is to "provide support for the school in its relationship with other institutions and interests in the local educational system" (p.155). In this model, the school provides an account to the governors, rather than being called to account. Kogan et al (1984) argues that the governors are likely to be involved in areas such as resources availability or management problems, rather than professional matters, eg. school objectives. The mediating model is based on

the premise that there are a number of different interests which have a stake in education. Each of these interests is valuable and has a vital role in the governing body. It does not specifically consider how accountability may operate. Levacic's (1994) study of the models indicates that none of the eleven governing bodies researched operated wholly on the basis of the accountable model. Its application was dependent on the personalities of individual governors. The advisory and supportive models were more applicable within the context of the governing bodies under review. These findings are consistent with those of Burgess et al's (1992) study of resource allocation in nine Sheffield schools. Governors were only actively involved in resource allocation in one of these schools. Levacic (1995:30) argues that the "apparent rarity of the governing body performing a major accountability role is related to the absence in schools of a fully developed rational approach to resource management". Whilst these models are useful for analysing the role of the governing body, they provide little evidence on both giving and being held to account Giving an account The governing body as a whole is obliged by legislation to give an account of the performance of the school. As section 1 of this paper indicates, governing bodies are required to provide information to parents, the LEA, central government, and the Office of Her Majesty's Inspectorate (OHMCI) inspectors. However, who do they feel accountable to? Governors in Warwickshire identified a range of groups. These included "the head and all staff, to the parents, the local community, local employers, other schools in the area, to the individual governors constituencies, the parish or diocesan authority and most strongly (although they did not think of it first) the children" (Beckett et al 1991:101). Apart from this, there has been little research conducted on who governors feel accountable to. How does accountability operate in practice? The vast majority of evidence on this issue concentrates on governing body accountability to parents. The main mechanism of accountability to parents is the annual report of the governing body and the annual meeting to discuss its content. Beckett et al (1991:98) state that the "legislation clearly indicates however that in the governors' annual meeting and report it is the governing body who will take the lead". Levacic (1995:39) argues that generally these are poorly attended by parents unless a special effort is made by the governors. The Audit Commission and OFSTED (1995) also recognise this problem and suggest ways in which annual reports and meetings can be improved in order to enhance parental accountability. In the joint Audit Commission and OFSTED (1995) report, the emphasis is clearly on accountability to parents for the school's performance. In addition to accounting collectively, individual governors may also give an account to the 'constituencies' they represent. Kogan et al (1984) found that each

governor knew what category of governor they were, but held differing views on representing their constituents. Parent governors found it difficult to represent parents, and many tried to give information and be in touch with parents through PTA meetings, parents evenings and talking to parents at the school gate. Teacher governors found it easier to represent their constituents as "findings could rapidly be taken, or meetings called, if a matter arose in which a teacher governor felt the need to canvass the views of his colleagues" (Kogan et al 1984:136). Whilst nominated or co-opted governors were aware that part of their role was representation, Kogan et al (1984) found that they had "surrendered their interest by joining the governing body, and were concerned only to use their affiliations and experience to support or advise the other governors and the school" (1984:137). Holding to account Clearly giving information, what Stewart (1984) calls the element of account, is not the only aspect of accountability. There is also the holding to account. Deem et al (1995:166) argue that "..few mechanisms are in place to make elected or selected governors accountable to those whose interests they represent". The sanctions of being removed from the governing body had not been used for parent, teacher or co-opted governors in their study. Levacic similarly (1995:30) states that there is an absence of "hotly contested elections" in the majority of schools. Hence few governors will have sanctions imposed. In order for the governing body to give an account, they need to be able to hold the headteacher to account for the performance of the school. Day and Klein (1987) found that this link was not evident in their study of LEA accountability. Members of the LEA felt they had little control over what happened in schools, but, despite this, were still accountable for it. The shift in responsibilities in the 1980s may mean simply that this problem has moved from the LEA to the governing body. One of the pre-requisites of holding to account is information to judge performance. Research (for example, Deem et al, 1995) suggests that governors find it difficult to obtain information, apart from that given to them by the professionals. Most, apart from the chair, spend very little time in the school, and those visits that they do make are largely concerned with school buildings maintenance (Deem and Brehony 1993). Much of the information they receive therefore comes from those who they need to hold to account. In summary, research suggests that many governors find it difficult to give an account, both collectively aand individually. Few of them will be held to account. In addition, the absence of 'objective' information and their lack of power suggests that they will find it difficult to hold the professionals to account. IV. Research Findings

This research is concerned with both the perceptions and practice of governing body accountability. The views and perceptions of governors are crucial. As Sinclair (1995:233) argues "accountability is not independent of the person occupying a position of responsibility, nor of the context. Defining accountability, the way it is internalised and experienced should be our focus". Gray and Jenkins (1985) similarly argue that insufficient attention has been paid to how and why accountability has been exercised. The evidence presented in this paper was gained from interviews with a range of governing body members in five primary and secondary schools within one LEA in a valleys authority in S. Wales. Of the schools, the two primary schools have 238 and 311 pupils and the secondary schools have 1092, 1295 and 1430 pupils enrolled. The schools were randomly selected from within the authority. Recognising that there are "many ideological, social, political and educational interests" operating within governing bodies, (Deem and Brehony, 1993:343), an attempt was made to interview a member from each of the main groups on each governing body: the headteacher, chair, teacher representatives, parents, LEAs and co-opted members. However, whilst this was not always possible due to individual availability, a range of governors from each school have been interviewed. The views and perceptions of 27 governors form the basis of this research. It is the intention of the researchers to extend this initial study to include the views and perceptions of a greater number of governors. The interviews took place during 1996/1997 academic year. Giving an account of performance is clearly an important aspect of accountability. The governors in our study identified a range of groups to which they were accountable, but the most common view was that they were accountable to parents. For example, a co-opted governor stated that they felt that "accountability has to be to parents to start with, but also there's public accountability involved and its channelled through the local authorities, so there's accountability there. So I think at the end of the day, it's go to be parents". Some felt that they were accountable to a group, that was wider than this, that is "the people within the catchment area of the school...especially the parents. And I suppose they act as the voice of the children". The view of all of the parent governors was that the governing body was accountable to parents. One, for example, felt that accountability "was to the parents. It's really them we're working for aren't we?". There were mixed feelings about the accountability relationship with the LEA. Most of the interviewees argued that governing bodies were still accountable to the LEA. For example, one Head said that "I think we are answerable to the LEA, the Director of Education, although there are some aspects of responsibility where the governing body has responsibility to work within rules...as I said we are responsible to the LEA for certain things, but ultimately we are responsible to parents". One teacher articulated the sanctions that the LEA has when asked who the governing body was accountable to: "at the end of the day this is the authority's school, educating the pupils of the authority, and at the end of the day if the governing body does not do its job right or is seen to be failing, then the Director of

Education obviously has the right to take back the school under direct control of the authority". Similarly a co-opted governor, stated that they were accountable "to the LEA. Obviously we are still part, as it is an LEA school, and accountable to at the end of the day". Some others omitted this level of government, stating that they were accountable to central government. They felt that they were "accountable to the Secretary of State for Wales. I don't know what the relationship between the governing body and the LEA is". Another teacher governor felt that governing bodies "are answerable to the government ultimately I suppose, the people who fund schools". Other governors felt that there was no clear sense of accountability to the LEA. For example, one argued that "I don't see a great stress on the accountability towards the LEA...I don't see the relationship being one of accountable to the LEA as daft as it may seem. I think accountability lies with the children, with the students in the school to ensure that it is a well run school". Another governor reversed the accountability of the governing body to the LEA to one of the accountability of the LEA to the governing body. He argued that "if we feel strongly about the way the LEA is acting on a particular matter, then we'll have no qualms about asking the clerk (of the governors) to write a letter expressing our views". Many of the governors felt that the governing body was not directly accountable to inspectors. One co-opted member argued, for example that "I don't think we are answerable to the outside inspectors. We're accountable to parents, yes, definitely and any criticisms or advice given in the inspectors report, we are answerable to them to put that right, to the benefit of the parents and the children". One teacher governor felt that following an inspection "changes started to happen, then we were all into the accountability stuff and the business people coming in and saying, well this isn't good enough you know...and there were strong feelings from business ends certainly, about a certain department which wasn't working and had not been working since the time of the inspection before and nothing had been done about it". Another teacher governor felt that the governing body was only accountable when things went wrong. She argued that "I'm not sure they (governing bodies) are accountable to anybody, unless of course something goes wrong and then they are accountable to whoever it is". A chair felt that "there has to be some accountability to them (parents) because if there is a mistake that is going to be made, then it's the parents, who are most likely to question decisions that are made". Some governors also felt that the governing body were also accountable to those living in the catchment area, not just to the parents. There was a feeling that schools had to reflect the values of the community and to ensure support for their activities. For example, one teacher governor highlighted the issue of school uniform purchase and the recommendation made by the governing body that these should be purchased from a particular local outlet. This decision was taken on the basis of the school's desire to be community-based.

Governors also felt individually accountable. Different constituencies of governors tended to give different views about this. Co-opted members, in general, were more likely to be unsure who they were accountable to. For example, one co-opted member argued that "quite where my accountability fits into this, as a co-opted member, I'm not sure, unless it's to my party (Labour) in this particular case". Another co-opted member felt that he was not accountable: "I have never felt accountable and I have never felt part of the decision making process". Others felt accountable, to some extent, to those who had co-opted them. The perception was that this was because of their expertise. As one member argued "well, obviously I am co-opted by the main governing body. I assume as there are five of us who are co-opted they want us for some expertise...So, yes accountable to the governing body who co-opted me". Teacher governors all felt individually accountable to their fellow teachers. Many sought the views of staff over some items on the agenda and reported back after governors meetings. This tended to be done formally when there were particularly contentious issues, such as the proposal to consider GM status, and was not a regular event. One teacher explained that "If I see anything coming up and I know the staff are going to be up in arms about it, then I call a meting of staff and say 'look this is coming up, what tactic do you want us to take?' We represent the staff I suppose, but we are not actually delegates, we don't go there because of the staff, and we can vote whichever way we want". Another teacher felt very clearly that his role was to represent the staff: "individually I am responsible to the members of staff because they have elected me and as such they can also de-select or throw me out or have a vote-of-no-confidence, or what-have-you." Whilst teacher governors felt accountable to colleagues in the workplace, parent governors, in contrast, did not feel that they could possibly be held accountable by all parents in a school. They regarded their role as one of providing support to the school and to assist with the provision of "a good education for both my children and others". There was a view amongst other governors that, at least initially, some parents acted on an individual basis on the governing body. A co-opted governor argued that a parent "came with a very vested interest in his boys reaching A levels. I think parent governors tend to be initially into that. But once they get in, they do begin to see the wider view of resources that need to be in place". At an individual level, LEA governors did not feel accountable to the LEA. One member argued "I have been appointed and they leave me to it". Another, when asked whether she felt accountable to the LEA responded simply "not as yet". LEA members typically felt that their input into school governing bodies was concerned with both the provision of information relating to new legislation and initiatives and also one of information feedback to the LEA. Few of the governors felt that the annual meeting was an effective mechanism of accountability. The meeting, which provides the forum for discussion of the annual

report, is attended by only a few parents in any of the schools. One governor stated, "you get ten parents turning up and you've got twenty governors there". Another said that "the attendance will be appalling, but then equally we don't make any attempt to make it more fun. The agenda is a standard one for all schools and is extraordinarily boring". Many felt that a low turnout at the meeting was an indication that parents were happy with the school, so for example, "I feel it is a compliment because they trust the school". In all schools, apart from one in our study, the preparation and writing of the annual report and the school prospectus was done by the head and others within the school and then passed to governors for comments and amendments. One governing body had a small PR sub-committee to take charge of it and the chair commented that "this year we have made a conscious effort to try and write more of it (the annual report) ourselves and take some of the work off the school, although it is not a perfect way of working, but we take responsibility for getting it printed and delivered". One headteacher highlighted that the annual report for her school included the information which it is legally obliged to contain and as such it is "not very user friendly to parents, it's not that they do not understand it, but the terminology is not user friendly". This particular school is committed to examining the presentation and content of the report in order to make it more appealing and attractive for parents. Informal mechanisms of accountability also operated in all schools. These included school newsletters, reports of success in the local media and informal meetings with governors. One parent governor, for example, typically stated the she was frequently approached by other parents when she goes to the school to pick up her children. In one of the schools, the governing body have met with student representatives of the sixth form in order to put forward their ideas. These informal mechanisms of accountability are widely considered to be effective by individual governors. None of those governors interviewed could recall any governor not being reelected, or any co-opted governor being removed from office. The only case of governors being removed from office was the case of the chair of one governing body, who was deselected as chair, as he had been one of the main instigators of a failed move for grant maintained status. Whilst not a deselection, a governor at one of the schools involved in this research actually withdrew herself from the governing body of another institution because she did not feel that she was "doing any good there. I feel that the chair is weak and not in control and I don't want to be associated with the decisions that are coming out of that governing body". Few of the governors felt that their role was to hold the headteacher to account for the performance of the school. Most described the operation of the governing body as the headteacher putting forward ideas and these being discussed. One described this as "the governing body questions most things. Not in terms of opposing what is

proposed very often, but just seeking further information. Very often it is a consensus, but nothing goes through on the nod, the head or ourselves as staff certainly couldn't put anything over their heads" (teacher governor). Whilst some governors felt that the headteacher was in control, the majority of governors felt that they were involved in the school and its management. Most felt that whilst the headteacher and the senior management team were responsible for the day-to-day running of the school, they, as governors, were responsible for setting policy. However, some did not agree with this. When one teacher was asked whether she thought management or the governing body establish strategy, she replied "No, I think the Head does everything...Its the Head who comes in and says 'well look, we must discuss these, this is the agenda' (for the governing body)". Another said that their role was "essentially to review and monitor performance in resources terms, performance terms, that's how I perceive it". The majority of governors got all their information from the Head. One governor stated that "most of the information we get is from the Head, in fact I can't think of anything that isn't". Some governors visited the school, but on an occasional basis. One headteacher stated that "governors have not been involved in any classroom observation or anything like that, but certainly visits to the school to discuss various aspects of school life". All the secondary school governing bodies analysed examination results, and one governor said that "we created hell last year because the examination results were so low". In general, headteachers' did not encourage governors to visit schools uninvited. V. Responsibility and Accountability? School governing bodies have been allocated new responsibilities as a result of the educational reforms. To what extent are they accountable for the exercise of these responsibilities ? Accountability involves both the element of account and the holding to account. With respect to the element of account, governing bodies are expected to provide information to a number of interests on the performance of a school/institution. In order for accountability to operate effectively, the information must be evaluated and appropriate action taken in response. This research has focused on how individuals on governing bodies perceive the accountability of the governing body. The majority of governors feel that the governing body is accountable to parents in the first instance and to a lesser extent the LEA. A few governors also highlighted accountability to those living within the catchment area as a whole. Whilst not feeling directly accountable to the inspection authorities, governors perceived themselves to be accountable for the performance of the school indicated in an inspection report. Governors were clear about their accountability to parents. In contrast, there was less clarity about their accountability to the LEA. The widespread awareness amongst governors that their powers over school management have been enhanced appears to have affected their perception of the accountability relationship to the

LEA. Apart from having a general perception that the school must operate within legal and financial requirements, the vast majority of governors were unaware about what governing bodies actually account to the LEA for, and the way in which this operated. Headteacher governors were much more aware of their accountability obligations to the LEA than other governors. This suggests that headteachers are more involved in accounting to the LEA than the governing body. This finding fits into the wider arguments by those such as Walsh (1995:177) about the role of individual governors in comparison with that of the headteacher on the governing body. He argues that "the governing body has gained power, but its influence is often limited compared with that of the headteacher, and as the degree of hierarchical control by the local education authority has declined, that within the school has increased". This research has highlighted the accountability felt by individual governors to their constituencies. Teacher governors felt that an important aspect of their role as a governor was both to represent the views of staff within a school and to report the decisions of the governing body back to staff. In contrast, parent governors, who have also been elected, did not perceive direct accountability back to parents as part of their role. This may be because of the more diverse range of parental interests which exist within a school or may be a function of the fact that parents do not often meet as a group. Co-opted governors and LEA members were least aware of any level of individual accountability to their constituents. These findings support those of Kogan et al (1984). In this research, governors were aware of their accountability to parents - that they must formally provide an annual report, a school prospectus and conduct an annual meeting. The central issue is the effectiveness of these mechanisms of accountability to parents. With the exception of one school, the majority of governors felt that they had little involvement in the preparation of either the annual report or the school prospectus. The governors felt that these documents were written by the headteacher and the school management team. The high level of involvement of the headteacher and the school, rather than the governors, suggests that these mechanisms of governor accountability to parents could be strengthened. As it currently operates, this mechanism of accountability exists from the headteacher to parents, rather than from the governing body. In addition, the accessibility of the annual report to parents requires examination. The Audit Commission and OFSTED (1995:16) have raised this issue in their report on school governing bodies. In their report, it is argued that "parents are likely to read reports which are written in a clear and accessible style and are enlivened by illustrations". The governing body which has taken responsibility for the annual report in this research appears to have a much more involved role than other governing bodies and, consequently, a more effective means of accountability to parents. The annual report and meeting is a mechanism of giving an account of performance, but the meeting is also an opportunity for parents to hold the

governing body to account. All governors reported the apparent lack of parental interest in the annual meeting at which the annual report is discussed. The meeting, which provides the forum for parents to raise specific issues about the annual report and the school more generally with those who have responsibility for them, must, as one of the key mechanisms of accountability, therefore be considered ineffective. This is because parents have not 'held the governing body to account rather only the 'element of account' is present. One of the governing bodies in this research is attempting to address this problem by conducting the annual meeting with parents at a different time in the school calendar, possibly on the same evening as a meeting of the school PTA. This initiative may serve to enhance the effectiveness of the annual meeting to parents as a mechanism of accountability in the future. Governors were not held to account as a group at the annual meeting. In addition they were rarely held to account as individuals by those that they represented. Just as Levacic (1995) found, few governors in out study had the sanctions of not being re-elected or co-opted for another period of office. The Conservative Government (DfEE 1996:5) has suggested that governing bodies are also accountable to "the wider community". However, although governing bodies in this research perceive an accountability to the communities in which they are located, no formal mechanism by which governing bodies can account to this group actually exists. In the absence of a mechanism of accountability, it can be argued that governing bodies are not formally accountable to their communities at all. Informally, a school governing body may wish to consider "the wider community" in making decisions. Additionally, any information which governing bodies provide to the community represent the element of 'giving an account', rather than being 'held to account'. The operation of the more informal mechanisms were viewed by many governors as important in terms of accountability to parents, prospective parents in the school catchment area and the wider community more generally. However, whilst there was a perception that informal approaches to accountability such as these were effective, this is dependent on the individuals' willingness to become involved and undertake relations at this level. Clearly, the 'holding to account' element of accountability may not always be present in informal approaches. However, this may exist where governors are dependent on the support of their constituents in their re-election to the governing body. None of the governors in this research felt that they held the headteacher to account. The governors' role was to comment on documentation and policy proposals which usually originated from the headteacher. This suggests that, of Kogan et al's (1984) models of governing bodies, the accountable model is the least dominant. Rather, governing bodies perform a mixture of advisory and supportive roles. In the majority of cases the head gave an account to the governing body, rather than the governing body exercising their authority to hold the head to account. The absence of headteacher accountability to the governing body found in

this paper has also been found by Deem and Brehony (1993:347). In this study, the authors noted that all of the headteachers "set out to 'manage' their governors" where they were able to "control, determine or influence significantly, the decisions governors made and limit the extent of governor involvement in the day-to-day running of the school". More effective accountability at this level is dependent on governor involvement and participation in decision making. Conclusion The enhancement of the power of governing bodies has impacted on accountability. Governors feel that they accountable to the parents and students of their schools. Their perception of LEA, inspection authority and catchment area accountability is weaker than that attached to parents. The element of 'holding to account' and the mechanisms to secure this are important aspects of accountability. Governor awareness of their accountability to parents is clearly apparent. However, the mechanisms by which this accountability is secured could be made more effective. The annual meeting with parents is viewed by governors as a key element of accountability. However, governors, on the whole, were resigned to a lack of parental interest in the meeting. The decision of one school to hold the meeting at a different time in the school year may encourage governors to view this as a more effective means of their accountability to parents. Placing responsibility for the annual report with the governing body, rather than with the headteacher, may also enhance governor perception of this mechanism of accountability. Further, governor involvement in the mechanisms of accountability to the LEA may improve awareness of their accountability to this group. In conclusion, the perception amongst individual governors is that governing bodies are accountable. Primarily, governors are fully aware of their accountability relationship with parents. The nature of their accountability to the LEA, inspection agencies and to those within the catchment areas requires some clarification amongst the governors of individual schools. Once clarified, the mechanisms by which accountability is secured need to be re-examined so that governors are not just responsible for schools - they are also fully accountable for them. Bibliography Audit Commission and OFSTED. 1995. Lessons in Teamwork: How School Governing Bodies Can Become More Effective. London: HMSO. Beckett, C., L. Bell and C. Rhodes. 1991. Working with Governors in Schools. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Boyett, I. and D. Finlay. 1996. 'Corporate Governance and the School Head Teacher'. Public Money and Management. April-June. Burgess, R.G. et al. 1992. Thematic Report and Case Studies. Sheffield: Sheffield City Council. Day P. and R. Klein. 1987. Accountabilities: Five Public Services. London: Tavistock. Deem, R. and K.J. Brehony. 1993. 'Consumers and Education Professionals in the Organisation and Administration of Schools: Partnership or Conflict?' Educational Studies. Vol.19. No.3 pp.339-355. Deem, R., K. Brehony and S. Heath. 1995. Active Citizenship and the Governing of Schools. Buckingham: Open University Press. Department of Education and Science. 1992. Choice and Diversity: A New Framework for Schools. London: HMSO. Department for Education and Employment. 1996. Guidance on Good Governance. London: Department for Education and Employment. Dunsire, A. 1978. Control in a Bureaucracy. The Execution Process. Vol.2. Oxford: Martin Robertson. Gray, A. and W. Jenkins. 1985. Administrative Politics in British Government. Brighton: Wheatsheaf. Farrell, C.M. and J. Law. 1995 Educational Accountability in Wales, York: York Publishing Services for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Kogan, M. 1986. Educational Accountability. An Analytic Overview. London: Hutchinson. Kogan, M., D. Johnson, T. Packwood and T. Whitaker. 1994. School Governing Bodies. London: Heinemann. Levacic, R. 1994. 'Evaluating the Performance of Quasi-Markets in Education', In Bartlett, W., Propper, C., Wilson, D., and LeGrand, J. (Eds.) Quasi-Markets in the Welfare State. Bristol: Saus Publications. Levacic, R. 1995. 'School Governing Bodies: Management Boards or Supporters' Clubs?'. Public Money and Management April-June. Ranson, S. 1986. 'Towards a Political Theory of Public Accountability in Education' Local Government Studies No. 4 pp.77-98.

Sallis, J. 1988. Schools, Parents and Governors: A New Approach to Accountability London: Routledge. Sinclair, A. 1995. 'The Chameleon of Accountability: Forms and Discourses' Accounting, Organisations and Society. Vol.20 No.2-3 pp.219-237. Stewart, J. 1984. 'The Role of Information in Public Accountability'. in A. Hopwood and C. Tomkins (eds.) Issues in Public Sector Accounting. Oxford: Phillip Alan. Tomlinson, J. 1993. The Control of Education. London: Cassell. Walsh, K. 1995. Public Services and Market Mechanisms: Competition, Contracting and the New Public Management. Hampshire: Macmillan. Welsh Office. 1993. School Governors: A Guide to the Law. Cardiff: Welsh Office

Вам также может понравиться

- Reimagining Schools and School Systems: Success for All Students in All SettingsОт EverandReimagining Schools and School Systems: Success for All Students in All SettingsОценок пока нет

- SP Enrolment Discussion PaperДокумент39 страницSP Enrolment Discussion PaperKay HughesОценок пока нет

- Titles With Legal IssuesДокумент5 страницTitles With Legal IssuesHAZEL LABASTIDAОценок пока нет

- Oday Accountability and TestingДокумент37 страницOday Accountability and TestingKaterina SalichouОценок пока нет

- Grassroots to Government: Creating joined-up working in AustraliaОт EverandGrassroots to Government: Creating joined-up working in AustraliaОценок пока нет

- Interview TransciДокумент20 страницInterview TransciMiracle December Neo AgapeОценок пока нет

- ASSIGNMENT 1 - DIGNOS, LYNHYLL JOY - Educ 302Документ3 страницыASSIGNMENT 1 - DIGNOS, LYNHYLL JOY - Educ 302lynhyll joy rabuyaОценок пока нет

- PUP GG & CSR IM Summer 2021Документ48 страницPUP GG & CSR IM Summer 2021Lye Fontanilla100% (1)

- Law Children Act 2004 Summary 1 1Документ6 страницLaw Children Act 2004 Summary 1 1Anonymous vs6YzCОценок пока нет

- Dissertation On Rte Act 2009Документ7 страницDissertation On Rte Act 2009CollegePapersWritingServiceCanada100% (1)

- RA. 8292 Critique EssayДокумент3 страницыRA. 8292 Critique EssayMikaela LoricaОценок пока нет

- Educational Governance in California: Evaluating The "Crazy Quilt"Документ5 страницEducational Governance in California: Evaluating The "Crazy Quilt"vlabrague6426Оценок пока нет

- Stewart Ranson-Public Accountability in The Age of Neo-Liberal Governance - Journal of Education Policy, Vol. 18, No. 5, Pp. 459-480, 2003Документ22 страницыStewart Ranson-Public Accountability in The Age of Neo-Liberal Governance - Journal of Education Policy, Vol. 18, No. 5, Pp. 459-480, 2003J. Félix Angulo RascoОценок пока нет

- Inclusive and Special EducationДокумент3 страницыInclusive and Special EducationVeselina KronosОценок пока нет

- Adult Education in Transition: A Study of Institutional InsecurityОт EverandAdult Education in Transition: A Study of Institutional InsecurityОценок пока нет

- Reflection 4Документ2 страницыReflection 4Fatima Naima SampianoОценок пока нет

- The Nature Scope and Function of School Administration Hand Outs 2nd GroupДокумент8 страницThe Nature Scope and Function of School Administration Hand Outs 2nd GroupMary Flor CaalimОценок пока нет

- Description: Tags: 1system2Документ71 страницаDescription: Tags: 1system2anon-556735Оценок пока нет

- Corporate Governance: Ensuring Accountability and TransparencyОт EverandCorporate Governance: Ensuring Accountability and TransparencyОценок пока нет

- BinaryДокумент5 страницBinarymp23314Оценок пока нет

- Theories of Governance and New Public Management JapanДокумент24 страницыTheories of Governance and New Public Management Japanvison22100% (1)

- Educational Administration in PerspectiveДокумент4 страницыEducational Administration in PerspectiveЛеиа АморесОценок пока нет

- School-Based Management .....Документ23 страницыSchool-Based Management .....Mohd Shafie Mt SaidОценок пока нет

- The Wider Professional Practice FinalДокумент13 страницThe Wider Professional Practice FinalJohn Muthama MbathiОценок пока нет

- EDUC. 604 Policy Analysis and Decision Making: Meriam O. Carian MAED StudentДокумент5 страницEDUC. 604 Policy Analysis and Decision Making: Meriam O. Carian MAED StudentRolando Corado Rama Gomez Jr.100% (1)

- Aet Homework Laws 1Документ2 страницыAet Homework Laws 1sharon.shawОценок пока нет

- What Keeps Texas Schools From Being As Efficient As They Could Be?Документ14 страницWhat Keeps Texas Schools From Being As Efficient As They Could Be?txccriОценок пока нет

- Social Responsibility Among High Education Institutions: An Exploratory Research On Top Ten Universities From Brazil and WorldДокумент7 страницSocial Responsibility Among High Education Institutions: An Exploratory Research On Top Ten Universities From Brazil and WorldticketОценок пока нет

- The Passage of "No Child Left Behind" (NCLB)Документ3 страницыThe Passage of "No Child Left Behind" (NCLB)Leornard MukuruОценок пока нет

- Teacher InductioДокумент22 страницыTeacher InductioFelipe HollowayОценок пока нет

- Educ205N-A-Fiscal Management of Educational Institution: DATE/TIME: 3:30-7:30 PM Activity 3Документ5 страницEduc205N-A-Fiscal Management of Educational Institution: DATE/TIME: 3:30-7:30 PM Activity 3Lilian BonaobraОценок пока нет

- Paul Hill ReportДокумент14 страницPaul Hill ReportKimberly ReevesОценок пока нет

- Action Research - Tan LeeДокумент19 страницAction Research - Tan Leearveena sundaralingamОценок пока нет

- 1-2 Accountability in SchoolsДокумент25 страниц1-2 Accountability in SchoolsIway ArnielОценок пока нет

- Reforming the Reform: Problems of Public Schooling in the American Welfare StateОт EverandReforming the Reform: Problems of Public Schooling in the American Welfare StateОценок пока нет

- Labor Relations Research PaperДокумент6 страницLabor Relations Research Paperafeawjjwp100% (1)

- Building Together: Collaborative Leadership in Early Childhood SystemsОт EverandBuilding Together: Collaborative Leadership in Early Childhood SystemsОценок пока нет

- Ekonomi Pembiayaan PendidikanДокумент26 страницEkonomi Pembiayaan PendidikanSaiful AlmujabОценок пока нет

- Transforming Schools An Entire System at A Time: Michael FullanДокумент3 страницыTransforming Schools An Entire System at A Time: Michael FullanRaj RamannaОценок пока нет

- Managing The Intersection of Internal and External AccountabilityДокумент29 страницManaging The Intersection of Internal and External AccountabilityAlanFizaDaniОценок пока нет

- A Struggle For Translation: An Actor-Network Analysis of Chilean School Violence and School Climate PoliciesДокумент24 страницыA Struggle For Translation: An Actor-Network Analysis of Chilean School Violence and School Climate PoliciesSantiago CifuentesОценок пока нет

- Stakeholders in EducationДокумент4 страницыStakeholders in EducationRizwan AhmedОценок пока нет

- RB Baker-Miron Charter Revenue PDFДокумент56 страницRB Baker-Miron Charter Revenue PDFNational Education Policy CenterОценок пока нет

- Pointers For Comprehensive Examination 1. Conflict Theory of ManagementДокумент10 страницPointers For Comprehensive Examination 1. Conflict Theory of ManagementKezОценок пока нет

- PTA Case 2016Документ11 страницPTA Case 2016almorsОценок пока нет

- Name: ID Number: Title of Assignment: Final Reflective Assignment: The Role ofДокумент13 страницName: ID Number: Title of Assignment: Final Reflective Assignment: The Role ofMUHAMMAD OMERОценок пока нет

- GracelДокумент11 страницGracelGracel MaravillasОценок пока нет

- Internet Article Showing Utah DCFS Ordered To Implement Changes in Lawsuit-1Документ7 страницInternet Article Showing Utah DCFS Ordered To Implement Changes in Lawsuit-1Roch LongueépéeОценок пока нет

- MIMAROPA Region SUC's Faculty Associations A Base Line StudyДокумент20 страницMIMAROPA Region SUC's Faculty Associations A Base Line StudyInternational Journal of Advance Study and Research WorkОценок пока нет

- Social Responsibility Among High Education Institutions: An Exploratory Research On Top Ten Universities From Brazil and WorldДокумент7 страницSocial Responsibility Among High Education Institutions: An Exploratory Research On Top Ten Universities From Brazil and WorldticketОценок пока нет

- SOM Unit-2Документ24 страницыSOM Unit-2hiteshОценок пока нет

- CPI Education Reform White PaperДокумент13 страницCPI Education Reform White PaperHelen BennettОценок пока нет

- Final AFA 1 (B)Документ12 страницFinal AFA 1 (B)adnan2406Оценок пока нет

- Financial Accountability at Schools Challenges and ImplicationsДокумент22 страницыFinancial Accountability at Schools Challenges and Implicationsmurti51Оценок пока нет

- Unit 1.1 Outline Current Legislation Relevant To The Home-Based ChildcareДокумент8 страницUnit 1.1 Outline Current Legislation Relevant To The Home-Based ChildcarefegasinnovationsОценок пока нет

- Year 5 Exam-P1Документ11 страницYear 5 Exam-P1Indra ManiamОценок пока нет

- Action Verbs SearchДокумент1 страницаAction Verbs SearchIndra ManiamОценок пока нет

- Presentation 2Документ4 страницыPresentation 2Indra ManiamОценок пока нет

- Traceable Alphabet Letter XДокумент1 страницаTraceable Alphabet Letter XIndra ManiamОценок пока нет

- Scheme of Work For English Year 5 2014: Week Theme Specification GrammarДокумент12 страницScheme of Work For English Year 5 2014: Week Theme Specification GrammarIndra ManiamОценок пока нет

- Collective NounsДокумент6 страницCollective NounsIndra ManiamОценок пока нет

- Traceable Alphabet Letter ZДокумент1 страницаTraceable Alphabet Letter ZIndra ManiamОценок пока нет

- The Impact of Principals Tranformational PDFДокумент40 страницThe Impact of Principals Tranformational PDFIndra ManiamОценок пока нет

- EtikaДокумент37 страницEtikaIndra ManiamОценок пока нет

- Harris AlmaДокумент41 страницаHarris AlmaIndra ManiamОценок пока нет

- Corrective Actions MatrixДокумент3 страницыCorrective Actions MatrixIndra ManiamОценок пока нет

- Observation ScheduleДокумент1 страницаObservation ScheduleIndra ManiamОценок пока нет

- Name: - Grade and Section: - Date SubmittedДокумент3 страницыName: - Grade and Section: - Date SubmittedEmelyn V. CudapasОценок пока нет

- Sample Quality Manual ISO 9001-2015Документ33 страницыSample Quality Manual ISO 9001-2015remedina1968100% (2)

- OfferLetterДокумент27 страницOfferLetterNikhil KumarОценок пока нет

- IA - Research ProjectДокумент32 страницыIA - Research ProjectSAHARE CANO BADWAM-AlumnoОценок пока нет

- 01 Meaning and Importance of CommunicationДокумент12 страниц01 Meaning and Importance of CommunicationLakshmi Prasad CОценок пока нет

- Techniques of Instructional Media ProductionДокумент8 страницTechniques of Instructional Media ProductionAmos Kofi KukuborОценок пока нет

- PrepScholar SOP Sample 4Документ2 страницыPrepScholar SOP Sample 4Sampa pikikОценок пока нет

- Johari WindowДокумент5 страницJohari WindowSaptarshee MazumdarОценок пока нет

- XXXXXX Relevant Field of Studies: XXXX EIT Digital Master SchoolДокумент3 страницыXXXXXX Relevant Field of Studies: XXXX EIT Digital Master Schoolkhan rqaib mahmudОценок пока нет

- Confidentiality, Privacy, Access, and Data Security Principles For Health Information Including Electronic Health RecordsДокумент9 страницConfidentiality, Privacy, Access, and Data Security Principles For Health Information Including Electronic Health RecordsEric GozzerОценок пока нет

- Hgm4010n Hgm4020n Hgm4010nc Hgm4020nc Hgm4010can Hgm4020can enДокумент52 страницыHgm4010n Hgm4020n Hgm4010nc Hgm4020nc Hgm4010can Hgm4020can enaltamirОценок пока нет

- Technological Forecasting & Social Change: Wantao Yu, Gen Zhao, Qi Liu, Yongtao SongДокумент11 страницTechnological Forecasting & Social Change: Wantao Yu, Gen Zhao, Qi Liu, Yongtao SongZara AkbariОценок пока нет

- Suicide Postvention Toolkit: A Guide For Secondary SchoolsДокумент44 страницыSuicide Postvention Toolkit: A Guide For Secondary SchoolsRiéger Ribeiro da SilvaОценок пока нет

- GDAS PM Professions: PMP Study Group: Monique Howard December 4, 2008Документ28 страницGDAS PM Professions: PMP Study Group: Monique Howard December 4, 2008upendrasОценок пока нет

- Confidentiality Undertaking NSTPДокумент2 страницыConfidentiality Undertaking NSTPFranz PalenciaОценок пока нет

- Design 9 Flexible Learning Syllabus 2122Документ7 страницDesign 9 Flexible Learning Syllabus 2122Eryl David BañezОценок пока нет

- Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan Media and Information Literacy LessonДокумент5 страницSemi-Detailed Lesson Plan Media and Information Literacy LessonGrace Mapili100% (2)

- Project Report On: Management Information SystemsДокумент13 страницProject Report On: Management Information SystemsPrashant BedwalОценок пока нет

- Achieving Better Practice Corporate Governance in The Public Sector1Документ50 страницAchieving Better Practice Corporate Governance in The Public Sector1Edina KulcsarОценок пока нет

- SS01 Co6Документ2 страницыSS01 Co6Eman CavalidaОценок пока нет

- ESSAY WRITING Sample Essays Band 456Документ14 страницESSAY WRITING Sample Essays Band 456Khang Ni 康妮 FooОценок пока нет

- Creating and Issuing CorrespondenceДокумент44 страницыCreating and Issuing Correspondencebacevedo10Оценок пока нет

- Interactive Science Notebook Guidelines #1Документ3 страницыInteractive Science Notebook Guidelines #1ruther paulinoОценок пока нет

- Lecture 5: ParaphrasingДокумент3 страницыLecture 5: ParaphrasingmimaОценок пока нет

- Latest Judgments On Section 79 Information Technology ActДокумент3 страницыLatest Judgments On Section 79 Information Technology ActArjun MaheshwariОценок пока нет

- Cognitive Virtual Agents at SEB BankДокумент29 страницCognitive Virtual Agents at SEB BankDavid BriggsОценок пока нет

- Informatics Lab Act 1Документ8 страницInformatics Lab Act 1Slepy chngОценок пока нет

- Acaps Analysis Workflow PosterДокумент1 страницаAcaps Analysis Workflow Posteryamanta_rajОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Aquarian Theosophy June 28, 2017Документ10 страницIntroduction To Aquarian Theosophy June 28, 2017Eric L LundgaardОценок пока нет

- Case Study ITCДокумент13 страницCase Study ITCShaharul Islam BarbhuiyaОценок пока нет