Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Artikkel Skrevet Av Hilde Bergersen Publisert I The Journal of Stroke and Cerebrova

Загружено:

Arja' WaasОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Artikkel Skrevet Av Hilde Bergersen Publisert I The Journal of Stroke and Cerebrova

Загружено:

Arja' WaasАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Anxiety, depression and psychological well being two to five years post stroke

Hilde Bergersen1, Kathrine Frey Frslie1,2, Katharina Stibrant Sunnerhagen1,3, AnneKristine Schanke 1

1. Sunnaas Rehabilitation Hospital and Medical Faculty, University of Oslo, Norway. 2. Department of Biostatistics, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Oslo, Norway. 3. Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, Section of Clinical Neuroscience and Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

Financial support was given in part by Sunnaas Rehabilitation Hospital. Moral support and encouragement was given by the staff.

Corresponding author Hilde Bergersen, Sunnaas Rehabilitation Hospital, 1450 Nesoddtangen, Norway Telephone: +47 66 96 96 39; Mobile: +47 92 61 27 01 Telefax: +47 66 91 25 76 E-mail: hilde.bergersen@smartcall.no

Short title: Psychological well being long time after stroke

ABSTRACT Objectives: To explore psychological well being and the psychosocial situation in persons with stroke, two to five years after discharge from a specialized rehabilitation hospital. Material and methods: The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-30) and a questionnaire were mailed to 255 former patients. Results: Sixty-four percent answered (36% women), and the average age was 58 years. HADS identified problems in 47% (anxiety in 36% and depression in 28%) and GHQ-30 in 54%. About half had experienced periods of anxiety and/or depression since discharge. Most were satisfied with support by family/friends (88%), home ward (68%) and community therapy services (57%). Marital status was as in the general population. Conclusions: A long time after stroke almost half of the investigated stroke patients had psychiatric problems according to the questionnaires. This is higher than in the general population but is comparable with some other chronic, somatic populations in Norway.

INTRODUCTION It is well documented that depression is common after stroke (1, 2), although the numbers for many reasons vary greatly between studies (3, 4). The relationship between stroke and psychological disorders other than depression has been given little attention in the literature (5). The long term well being of stroke patients discharged from specialized rehabilitation is not documented.

Findings suggest that post stroke anxiety problems are common and both more stable and persistent than post stroke depression (6). strm (7) found generalized anxiety in 19 % three years after stroke, and a review (8) showed that two studies reported 17-18 % generalized anxiety after two years. Comorbid depression is common in stroke survivors with generalized anxiety disorder, and the existence of the anxiety disorder can negatively affect the prognosis of the depression (7).

The prevalence of depression decreases during the first year after stroke in both community studies and in institutionalized patients (3). However, as Hackett et al. (8) noted, there are also reports of long term follow-ups where possible depression was found in 18-38 % two to five years after stroke, depending on the study. The question remains of how common these problems are in the general stroke population. In a large scale Norwegian population survey, possible anxiety disorders, measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), were found in 16 % in the age group of 47-70 and possible depression in 13 % (Bjelland 2007, personal communication). In the subpopulation with prior stroke, possible anxiety disorders were found in 21% and possible depression in 27 % (9), and 11 % had comorbid anxiety/depression.

Long term emotional outcome in stroke survivors has also been studied with concepts such as quality of life or health related quality of life (HRQoL) (10). HRQoL is severely impaired in most stroke survivors two years post stroke (11) and has been found to be very low in 20 % still five years after stroke (12). Some studies have also found relatively satisfactory long term life quality (13), however, indicating that many stroke survivors adapt to their disabilities and dependency (14, 15).

Quality of life is still influenced by mental health in stroke survivors two to four years after stroke (10, 11, 16). Anxiety and depression are independent determinants of handicap (17), which again is associated with quality of life (11).

The aim of the study was to explore stroke survivors mental health, psychological well being and psychosocial situation two to five years after discharge from a specialized rehabilitation hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS The subjects were patients admitted to Sunnaas Rehabilitation Hospital for stroke. The hospital is a specialized inpatient rehabilitation centre located close to the capital city, Oslo. From the hospitals archives, 255 persons who had stayed at the hospital during 1998-2001, were identified as having had a stroke diagnosis (WHO criteria by a stroke physician and/or CT or MR verified).

A questionnaire was sent out by mail and a reminder sent out a few weeks later. The questionnaire contained the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (18), the General Health Questionnaire, 30 items (19, 20), and some structured questions regarding

psychosocial situation (marital status, employment, drivers licence and satisfaction with support from family and friends, help from the home ward and with the community therapists) and a self-report of psychological functioning in the period since discharge (existence of periods of anxiety and/or depression, contact with professionals for these problems and an evaluation of the helpfulness of this). For comparison, marital status data from the Norwegian statistical database were used (21). Demographic and medical information was collected from the patients medical journal at the hospital. The modified Rankin scale (22) was used to describe disability.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HADS, is a questionnaire with 14 items intermingled on two subscales (anxiety, HADS-A, and depression, HADS-D). It has good psychometric value (23) and general population norms and performs well in assessing symptom severity and meeting the criteria of anxiety disorders and depression, both in somatic, psychiatric and primary care patients (23). Zigmond and Snaith (18) suggested scores below 8 as within normal limits and above 10 as definite cases of anxiety or depression, and we used the generally accepted and recommended cut-off of 7/8, where a score of 8 or above suggests possible psychiatric morbidity. An authorized Norwegian version was used.

The General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) has been suggested to be suitable for screening mild psychopathology and quality of life (24). GHQ-30 contains more items on quality of life and fewer on somatic symptoms compared to the other versions of GHQ and is regarded as well suited for patients in primary care and in somatic hospitals. Each item can be recoded to 0 or 1. A total sum score over 5 indicates psychopathology (case). An authorized Norwegian version was used.

The respondents were also asked whether they had been through periods of anxiety and/or depression since discharge from the rehabilitation hospital, whether they had sought professional help for these problems and, potentially, the helpfulness of this. In addition they were asked whether they were satisfied with emotional and practical support of family and friends, and the range and service of primary health care and therapists in the community.

STATISTICAL ANALYSES Statistical Packages for Social Sciences (SPSS), 15.0, was used for the statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were counts and percentages of categorical data. Mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and quartiles were used as summary measures for numerical data. Comparisons of responders and non-responders were made by Pearsons 2 test (gender) and two-sample t-test (age). Correlations between measures were explored in scatter plots and estimated by Pearsons correlation coefficient (r). Factor analysis with varimax rotation was used to explore the two scales of the HADS. The agreement between HADS and GHQ-30 when they were used as diagnostic tests based on their respective cut-offs was explored in cross tables and quantified by Cohens . Kappa coefficients in the range 0.40-0.80 are considered moderate to good and those exceeding 0.80 very good, while values below 0.40 are fair to poor (25). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ETHICS Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Norwegian social science and data services and the Regional Committee for Ethics in Medical Research (REK I). The study was conducted according to Norwegian legislation on information gathering and storing.

RESULTS The answering process is described in figure 1. In 27 cases of comprehension deficits, proxies informed of having assisted, which was explicitly allowed for in a letter accompanying the questionnaire. Three responders answered by phone and one in a personal meeting. In the case of missing items, the responders were either phoned or mailed to complete missing items. In the end, four of these had to be omitted since they could not give information on the missing items even after contact. The final sample consisted of 162 persons (63.5%). These are referred to as responders. Information on the non-responders age and gender was available in the hospital administrative system, enabling comparison between responders and non-responders.

The respondents had had their stroke on average 3.5 years earlier (SD=1.2). Twelve percent (n=20) had also had a prior stroke. As usual, infarctions were the most common cause, but in this sample 14 % of the respondents had experienced a subarachnoidal haemorrhage (table 1). About 1/5 were diagnosed as having aphasia, severely affecting communication in everyday activities at the time of discharge from rehabilitation. Almost a third of the respondents was moderately severely disabled and in need of assistance for mobility and own bodily needs, scoring 4 on the Modified Rankin Score (MRS). The median MRS score was 3, indicating moderate disability; requiring some help, but able to walk without assistance. A comparison with the group of non-responders revealed no significant differences regarding gender or age. The majority was either in early retirement due to disablement (52 %) or age (29 %) at time of follow-up (table 2). Twentynine persons, none above the age of 61, were working, and 14 of these had a reduction in work time or adjusted vocational situation. Drivers licence had been permanently withdrawn in 44 % as a consequence of the stroke. The number of divorces was as expected

for the general Norwegian population in the same age group. The majority was satisfied with psychosocial and practical support of proxies and the community (see table 3). Some commented that they were more satisfied with their familys support than with their friends.

Eighty-seven respondents (54.5 %) reported having been through periods of anxiety (32.6 %) or depression (48.2 %) during the period since discharge (table 4), and almost half of these reported having experienced both (n=42). Of those reporting of periods of psychological problems, 53 % (n=52) had consulted professionals for this reason and the majority (38/52) had found this helpful. However, in spite of this, 86 % of those reporting periods of anxiety or depression some time during the period since discharge still suffered from possible psychiatric problems.

According to HADS, 36.4 % of the respondents had possible anxiety disorder (scores > 7), and 27.8 % had possible depression (see figure 2). The overlap was large, as 17.3 % of the respondents had comorbid anxiety disorder and depression according to HADS, meaning that nearly half of the depressed and two-thirds of the respondents with an anxiety disorder also had a possible comorbid psychiatric disorder. The average score in HAD-A was 5.8 (SD=5.0) and in HAD-D 5.6 (SD=4.0). Definite cases of anxiety or depression (cut-off 10/11) were 16.7 % and 8.0 %, respectively.

A total of 54 % of the respondents had a case score (score >5) on GHQ-30, indicating low quality of life and possible psychiatric morbidity. The two clearly most common case answers were about having a reduced social life (56 % cases) and being able to participate in a useful way (50 %).

GHQ-30 was correlated with both HAD scales (HAD-A: r=0.69; HAD-D: 0.69; p<0.001). The association between the two HAD scales was r=0.59 (p<.001). Varimax rotation with the HADS items supported the original two-factor solution, where item no 10 (I feel as if I am slowed down) had the weakest loading (0.4) on a subscale (HADS-D). The agreement between case HAD-D and case GHQ was =0.37 and between case HAD-A and case GHQ =0.41. According to reference limits (25), this is considered to be low.

DISCUSSION The aim of the study was to explore stroke survivors mental health, psychological well being and the psychosocial situation two to five years after discharge from a specialized rehabilitation hospital. We found that approximately half of the respondents had possible psychiatric morbidity and/or low quality of life as indicated by scores on the measurement instruments (HADS and GHQ-30). More than a third (36 %) suffered from a possible anxiety disorder and more than a fourth (28 %) from depression. Our results indicate that anxiety is at least as common as depression in severely affected stroke survivors two to five years after discharge from hospital. This may be in accordance with studies suggesting that anxiety is more stable over time than depression (6, 15).

The level of mental health problems in our study is somewhat higher than reported in previous findings (7-9), especially for anxiety. However, these numbers are surprisingly low considering the relatively poor functional level in this specific study group compared to other studies of stroke survivors (26, 27). Depending on the sample studied, the prevalence of post stroke depression varies up to fourfold (4). More severe disability in persons with stroke has been reported to be associated with lower mental health functioning (28, 29). Studies of samples recruited from hospital and rehabilitation settings generally include people with more

severe disability than community based studies, which might explain the higher prevalence of depression in the hospital and rehabilitation samples than in the community based studies. Severe and complex disability is a prerequisite for rehabilitation at Sunnaas Hospital. The patient group studied scored relatively high on the Modified Rankin scale (MRS), indicating physical impairments, and 20 % had aphasia that seriously affected communication, which is higher than expected in a stroke population (30). This might explain the relatively high psychiatric morbidity in our population compared to community based studies and studies of populations taken from general hospitals (stroke units).

Studies of the psychometric properties of HADS specifically in stroke populations (19, 31-33) indicate that lower cut-off values than the cut-off values originally suggested by Zigmond and Snaith (18) may be better in these populations. If this is correct, our estimates of psychiatric morbidity based on the original cut-off values may underestimate the problem.

In this study we noted co-existing anxiety and depression in 17 %. Half of the depressed persons also had an anxiety disorder, and more than two-thirds of the respondents with an anxiety disorder had depression as well. This possibly indicates that the HAD scores reflect a general psychological distress (5). This can be considered to be in accordance with an earlier Norwegian study of the general population (9), where somatic health problems were more strongly associated with co-existing anxiety and depression than with anxiety or depression each alone. An explanation of this might be, in accordance with Williams and Evans (34), that somatic illness contributes to an increased load of stressors that make subsyndromal depressions clinically significant. For whatever reason, it seems that the complex situation in the stroke population needs to be assessed as a whole.

10

In our sample the agreement between HAD scales and GHQ-30 was rather low. The relatively low agreement means that some stroke survivors with possible psychiatric morbidity report their quality of life to be satisfying and some survivors with no psychiatric morbidity report low quality of life, indicating that other factors than mental health add to explaining stroke survivors long term total quality of life.

Stroke survivors have been found to have greater contact with mental health care compared with the general population (35). Although many of the respondents in this sample reported having been through periods of anxiety and/or depression since discharge from the hospital, only half of these people had consulted health care professionals about this. These results suggest that they had not received the necessary help for their mental health problems. Perhaps health personnel should actively screen for these problems since the persons do not actively seek help.

In this population requiring specialized rehabilitation post stroke, mental distress was present years after discharge to a much higher degree than in the healthy population. The level was however in general accordance with some other chronic, somatic populations in Norway. One finding is that many persons with mental health problems did not seek or receive support from the health services for this.

References

1. Dennis M, O'Rourke S, Lewis S, et al. Emotional outcomes after stroke: factors

associated with poor outcome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000 Jan;68(1):47-52. 2. Linden T, Blomstrand C, Skoog I. Depressive disorders after 20 months in

elderly stroke patients: a case-control study. Stroke 2007 Jun;38(6):1860-1863.

11

3.

Aben I, Verhey F, Honig A, et al. Research into the specificity of depression

after stroke: a review on an unresolved issue. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2001 May;25(4):671-689. 4. Whyte EM, Mulsant BH. Post stroke depression: epidemiology,

pathophysiology, and biological treatment. Biol Psychiatry 2002 Aug 1;52(3):253-264. 5. Schramke CJ, Stowe RM, Ratcliff G, et al. Poststroke depression and anxiety:

different assessment methods result in variations in incidence and severity estimates. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1998 Oct;20(5):723-737. 6. Morrison V, Pollard B, Johnston M, et al. Anxiety and depression 3 years

following stroke: demographic, clinical, and psychological predictors. J Psychosom Res. 2005 Oct;59(4):209-213. 7. Astrom M. Generalized anxiety disorder in stroke patients. A 3-year

longitudinal study. Stroke 1996 Feb;27(2):270-275. 8. Hackett ML, Yapa C, Parag V, et al. Frequency of depression after stroke: a

systematic review of observational studies. Stroke 2005 Jun;36(6):1330-1340. 9. Stordal E, Bjelland I, Dahl AA, et al. Anxiety and depression in individuals with

somatic health problems. The Nord-Trondelag Health Study (HUNT). Scand J Prim Health Care 2003 Sep;21(3):136-141. 10. Haacke C, Althaus A, Spottke A, et al. Long-term outcome after stroke:

evaluating health-related quality of life using utility measurements. Stroke 2006 Jan;37(1):193-198. 11. Sturm JW, Donnan GA, Dewey HM, et al. Quality of life after stroke: the North

East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Stroke 2004 Oct;35(10):2340-2345.

12

12.

Paul SL, Dewey HM, Sturm JW, et al. Thrift AG. Prevalence of depression and

use of antidepressant medication at 5-years poststroke in the North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study. Stroke 2006 Nov;37(11):2854-2855. 13. Hackett ML, Duncan JR, Anderson CS, et al. Health-related quality of life

among long-term survivors of stroke: results from the Auckland Stroke Study, 1991-1992. Stroke 2000 Feb;31(2):440-447. 14. Jonsson AC, Lindgren I, Hallstrom B, et al. Determinants of quality of life in

stroke survivors and their informal caregivers. Stroke 2005 Apr;36(4):803-808. 15. Roman MW. Lessons learned from a school for stroke recovery. Top Stroke

Rehabil. 2008 Jan-Feb;15(1):59-71. 16. Clarke P, Marshall V, Black SE, et al. Well-being after stroke in Canadian

seniors: findings from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Stroke 2002 Apr;33(4):10161021. 17. Sturm JW, Donnan GA, Dewey HM, et al. Determinants of handicap after

stroke: the North East Melbourne Stroke Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Stroke 2004 Mar;35(3):715-720. 18. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta

Psychiatr Scand. 1983 Jun;67(6):361-370. 19. O'Rourke S, MacHale S, Signorini D, et al. Detecting psychiatric morbidity after

stroke: comparison of the GHQ and the HAD Scale. Stroke 1998 May;29(5):980-985. 20. Tarnopolsky A, Hand DJ, McLean EK, et al. Validity and uses of a screening

questionnaire (GHQ) in the community. Br J Psychiatry 1979 May;134:508-515. 21. Statisics Norway. Statistisk sentralbyr. [cited 2008; Available from:

http://www.ssb.no/emner/02/nos_befolkning/nos_c607/tab/t-208.html]

13

22. 23.

Burn JP. Reliability of the modified Rankin Scale. Stroke 1992 Mar;23(3):438. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and

Depression Scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res. 2002 Feb;52(2):69-77. 24. Goldberg D, Bridges K, Duncan-Jones P, et al. Detecting anxiety and depression

in general medical settings. Bmj. 1988 Oct 8;297(6653):897-899. 25. 1991. 26. Fjaertoft H, Indredavik B, Lydersen S. Stroke unit care combined with early Altman D. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman & Hall,

supported discharge: long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Stroke 2003 Nov;34(11):2687-2691. 27. Silvestrelli G, Parnetti L, Tambasco N, et al. Characteristics of delayed

admission to stroke unit. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2006 Apr-May;28(3-4):405-411. 28. Brodaty H, Withall A, Altendorf A, et al. Rates of depression at 3 and 15

months poststroke and their relationship with cognitive decline: the Sydney Stroke Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2007 Jun;15(6):477-486. 29. Castillo CS, Schultz SK, Robinson RG. Clinical correlates of early-onset and

late-onset poststroke generalized anxiety. Am J Psychiatry 1995 Aug;152(8):1174-1179. 30. Pedersen PM, Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, et al. Aphasia in acute stroke:

incidence, determinants, and recovery. Ann Neurol. 1995 Oct;38(4):659-666. 31. Aben I, Verhey F, Lousberg R, et al. Validity of the beck depression inventory,

hospital anxiety and depression scale, SCL-90, and hamilton depression rating scale as screening instruments for depression in stroke patients. Psychosomatics 2002 SepOct;43(5):386-393.

14

32.

Johnson G, Burvill PW, Anderson CS, et al. Screening instruments for

depression and anxiety following stroke: experience in the Perth community stroke study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995 Apr;91(4):252-257. 33. Tang WK, Wong E, Chiu HF, et al. Rasch analysis of the scoring scheme of the

HADS Depression subscale in Chinese stroke patients. Psychiatry Res. 2007 Feb 28;150(1):97-103. 34. Williams H, Evans J. Brain injury and emotion: an overview to a special issue

on bio-psycho-social in neurorehabilitation. Neuropsychological rehabilitation 2003;13(1/2):1-11. 35. Driessen G, Evers S, Verhey F, et al. Stroke and mental health care: a record

linkage study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2001 Dec;36(12):608-612.

15

Figure legends 1. Flow chart of the recruitment process. 2. Scatter plot of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. The upper right quadrant depicts those persons with both depression and anxiety. The lower left quadrant shows those with neither depression nor anxiety. The upper left identifies a dominance of anxiety and the lower right a dominance of depression.

16

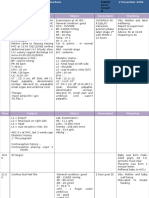

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the 162 respondents n Cause of stroke Infarction Left: n=45 (45 %) Right: n=33 (33 %) Other: n=23 (23 %) Haemorrhage Subarachnoidal Both infarction and haemorrhage Unknown 30 (19 %) 22 (13 %) 4 (3 %) 5 (3 %) 101 (62 %)

17

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of the respondents at follow-up n Male Female Years since stroke Age (22-85) Education (7-18) Marital status Married/cohabitant Divorced Widow/widowers Single, never married 107 25 10 20 (66 %) (15 %) (6 %) (12 %) 104 58 (64 %) (36 %) 3.5 58.3 11.5 1.2 11.8 3.0 Mean SD

Drivers licence revoked Income Retirement Disability pension Employment same job: n=11 (7 %)

67

(44 %)

47 86 29

(29 %) (53 %) (18 %)

reduced time: n=14 (9 %) new job: n=4 (3 %)

18

Table 3: Self-reported satisfaction Satisfied, n Psychosocial support from proxies Community rehabilitation Practical help from home ward 142 (88 %) 89 (57 %) 103 (68 %) 37 (24 %) 32 (21 %) Partly satisfied, n Not satisfied, n 20 (12 %) 31 (20 %) 17 (11 %)

19

Table 4: Self-reported psychiatry in the period since discharge (n, %) Periods with anxiety only Periods with depression only Both anxiety and depression No depression or anxiety 10 (6 %) 35 (22 %) 42 (26 %) 73 (46 %)

20

Figure 1

n= 255 questionnaires

n=10 persons with severe aphasia according to proxies

n=4 questionnaires with missing items n=79 non-responders

n=162 in the study

21

Figure 2: The respondents scores on HADS. The horizontal and vertical lines represent the cut-off values for anxiety and depression (7/8), respectively.

20

Anxiety only n=31 (19 %)

Anxiety and depression n=28 (17 %)

HADS, Anxiety scale

15

Number of persons 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

10

5 Depression only n=17 (11 %) 0 0 5 10 15 HADS, Depression scale 20

22

Вам также может понравиться

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (894)

- PTSD and Forensic PsychologyДокумент126 страницPTSD and Forensic PsychologyTúОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- MCQДокумент5 страницMCQJagdishVankar100% (1)

- Mood DisordersДокумент606 страницMood DisordersCarlos Hernan Castañeda RuizОценок пока нет

- Primal ScreamДокумент9 страницPrimal ScreamVladimir Bozic100% (1)

- PhobiasДокумент35 страницPhobiasRicardo GarciaОценок пока нет

- Psychiatric Patient Assessment Case StudyДокумент3 страницыPsychiatric Patient Assessment Case StudymichaelurielОценок пока нет

- Psychoanalytic Therapy - Group 1Документ74 страницыPsychoanalytic Therapy - Group 1Naomi Paglinawan100% (2)

- Dissociative Identity DisorderДокумент8 страницDissociative Identity DisorderhasanОценок пока нет

- Self, Solipsism, and Schizophrenic DelusionsДокумент21 страницаSelf, Solipsism, and Schizophrenic Delusionsjcrosby77Оценок пока нет

- Relevence of Psychoanalytical Theory in Modern PsychologyДокумент3 страницыRelevence of Psychoanalytical Theory in Modern PsychologyWilroОценок пока нет

- AutismДокумент11 страницAutismapi-3005480250% (1)

- Academic Essay: Comparison & Contrast: (Person Centered, Gestalt and Transactional Analysis)Документ8 страницAcademic Essay: Comparison & Contrast: (Person Centered, Gestalt and Transactional Analysis)Sundas RehmanОценок пока нет

- (David Kissane, Barry Bultz, Phyllis Butow, Ilora PDFДокумент773 страницы(David Kissane, Barry Bultz, Phyllis Butow, Ilora PDFAnonymous YdFUaW6fB100% (1)

- Solusio Plasenta 20-10-2012Документ4 страницыSolusio Plasenta 20-10-2012Arja' WaasОценок пока нет

- MR Obgyn 17 Okt 2012 - KetДокумент7 страницMR Obgyn 17 Okt 2012 - KetArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Morning Report 20th October 2012 - DistosiaДокумент5 страницMorning Report 20th October 2012 - DistosiaArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- 20 DESEMBER 2009: Morning ReportДокумент6 страниц20 DESEMBER 2009: Morning ReportArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- MR 2-12-2009aДокумент2 страницыMR 2-12-2009aArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Supervised By: Dr. Punarbawa Spog: Morning ReportДокумент19 страницSupervised By: Dr. Punarbawa Spog: Morning ReportArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Morning Report 26th October 2012 - SerotinusДокумент11 страницMorning Report 26th October 2012 - SerotinusArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- KPD Minggu 9 LalaДокумент7 страницKPD Minggu 9 LalaArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Supervisor: Dr. Edi Prasetyo Wibowo Spog: 2 NOVEMBER 2009Документ4 страницыSupervisor: Dr. Edi Prasetyo Wibowo Spog: 2 NOVEMBER 2009Arja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Morning Report 26th October 2012 - EklampsiДокумент9 страницMorning Report 26th October 2012 - EklampsiArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- KPD Minggu 9 LalaДокумент7 страницKPD Minggu 9 LalaArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Morning Report 11th October KPD (Death Case)Документ7 страницMorning Report 11th October KPD (Death Case)Arja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Eklamsi 20-10-2012Документ7 страницEklamsi 20-10-2012Arja' WaasОценок пока нет

- 051209Документ10 страниц051209Arja' WaasОценок пока нет

- CTH MR 301009Документ9 страницCTH MR 301009Arja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Death Case HPPДокумент11 страницDeath Case HPPArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- 291109Документ7 страниц291109Arja' WaasОценок пока нет

- DMG + Macrosomnia + APBДокумент9 страницDMG + Macrosomnia + APBArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- 20 DESEMBER 2009: Morning ReportДокумент6 страниц20 DESEMBER 2009: Morning ReportArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- 141209Документ9 страниц141209Arja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Morning Report: Supervised By: Dr. Edi P.W. SpogДокумент10 страницMorning Report: Supervised By: Dr. Edi P.W. SpogArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Age: 18 Years Address: Pringgarata: Time Subject Object Assesment PlanningДокумент4 страницыAge: 18 Years Address: Pringgarata: Time Subject Object Assesment PlanningArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- 03-07-12 PEB+riw. SCДокумент6 страниц03-07-12 PEB+riw. SCArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- 8 NOVEMBER 2009: Morning ReportДокумент10 страниц8 NOVEMBER 2009: Morning ReportArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Supervised By: Dr. Punarbawa Spog: Morning ReportДокумент19 страницSupervised By: Dr. Punarbawa Spog: Morning ReportArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- 200Документ3 страницы200Arja' WaasОценок пока нет

- 051209Документ10 страниц051209Arja' WaasОценок пока нет

- 11-10-12 LetliДокумент5 страниц11-10-12 LetliArja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Jones Dec 07Документ5 страницJones Dec 07Arja' WaasОценок пока нет

- Control The Machine - Technology Addiction AwarenessДокумент2 страницыControl The Machine - Technology Addiction AwarenessPompi BanerjeeОценок пока нет

- PSYCH REPORT InstructionsДокумент6 страницPSYCH REPORT InstructionsvictoriaОценок пока нет

- Mental Health ServicesДокумент3 страницыMental Health ServicesAntonette NangОценок пока нет

- Domes 2013 Emotional Empathy and Psychopathy in OffendersДокумент18 страницDomes 2013 Emotional Empathy and Psychopathy in OffendersPutri AdnyaniОценок пока нет

- Daftar PusakaДокумент5 страницDaftar PusakaPramono SetyawanОценок пока нет

- Pharmacological Management of Agitation in Emergency SettingsДокумент8 страницPharmacological Management of Agitation in Emergency SettingsnurulnadyaОценок пока нет

- Stress BrochureДокумент2 страницыStress BrochurerjchpОценок пока нет

- Serie de Casos PDFДокумент10 страницSerie de Casos PDFJazmín CevallosОценок пока нет

- Body ShamingДокумент9 страницBody Shamingagus aminОценок пока нет

- The Borderline Personality by Elvis ObokДокумент3 страницыThe Borderline Personality by Elvis ObokOBOKОценок пока нет

- Vulnerable Groups in India: Chandrima Chatterjee Gunjan SheoranДокумент39 страницVulnerable Groups in India: Chandrima Chatterjee Gunjan SheoranThanga pandiyanОценок пока нет

- Self Rescue Manual SharedДокумент37 страницSelf Rescue Manual SharedDavid JordanОценок пока нет

- CANMAT 2016 Section 6. Special Populations Youth, Women and ElderlyДокумент16 страницCANMAT 2016 Section 6. Special Populations Youth, Women and ElderlyPablo NuñezОценок пока нет

- Articolul 4Документ8 страницArticolul 4ioanaОценок пока нет

- What Is Abnormal Anyway?: Chapter 13-Psychological DisordersДокумент31 страницаWhat Is Abnormal Anyway?: Chapter 13-Psychological DisordersJasmin ValloОценок пока нет

- Bipolar Disorder - RLE Case StudyДокумент3 страницыBipolar Disorder - RLE Case StudyKathleen DimacaliОценок пока нет

- 2019 PSRANM Conference Program FinalДокумент24 страницы2019 PSRANM Conference Program FinalKimmie JordanОценок пока нет